Abstract

Background

Manualized cognitive and behavioral therapies are increasingly used in primary care environments to improve nonpharmacological pain management. The Brief Cognitive Behavioral Therapy for Chronic Pain (BCBT-CP) intervention, recently implemented by the Defense Health Agency for use across the military health system, is a modular, primary care–based treatment program delivered by behavioral health consultants integrated into primary care for patients experiencing chronic pain. Although early data suggest that this intervention improves functioning, it is unclear whether the benefits of BCBT-CP are sustained. The purpose of this paper is to describe the methods of a pragmatic clinical trial designed to test the effect of monthly telehealth booster contacts on treatment retention and long-term clinical outcomes for BCBT-CP treatment, as compared with BCBT-CP without a booster, in 716 Defense Health Agency beneficiaries with chronic pain.

Design

A randomized pragmatic clinical trial will be used to examine whether telehealth booster contacts improve outcomes associated with BCBT-CP treatments. Monthly booster contacts will reinforce BCBT-CP concepts and the home practice plan. Outcomes will be assessed 3, 6, 12, and 18 months after the first appointment for BCBT-CP. Focus groups will be conducted to assess the usability, perceived effectiveness, and helpfulness of the booster contacts.

Summary

Most individuals with chronic pain are managed in primary care, but few are offered biopsychosocial approaches to care. This pragmatic brief trial will test whether a pragmatic enhancement to routine clinical care, monthly booster contacts, results in sustained functional changes among patients with chronic pain receiving BCBT-CP in primary care.

Keywords: Chronic Pain, Primary Care Behavioral Health, Integrated Primary Care, Pragmatic Trial

Introduction

Most patients with chronic pain are managed in primary care settings with a generally ineffective combination of medications and referral to specialty care [1]. As in civilian health care facilities, treatment approaches for chronic pain in the military have traditionally focused on medical interventions, including the use of medications and surgeries [2]. In general, primary care practitioners report feeling unprepared to treat chronic pain and often rely on opioid medications [3]. Unfortunately, opioids are a poor frontline treatment for chronic pain, with significant risk for misuse, abuse, and death [4].

Recognizing these concerns, the U.S. Army assembled a Pain Management Task Force in 2009 with the mission of describing the extent of chronic pain problems among war-injured military members and outlining gaps in chronic pain management resources throughout the Department of Defense (DOD) and Veterans Health Administration medical systems [5]. The Pain Management Task Force identified the most notable gaps in DOD pain management as 1) the need for effective biopsychosocial interventions for pain management in primary care (where most patients with pain are seen), 2) consideration of military relevance among pain management programs to ensure their uptake among military service members with chronic pain, and 3) the need for chronic pain management programs that can demonstrate decreased misuse of opioids. Addressing these gaps was identified as being vital to providing the best care possible for military service members and veterans with chronic pain and likely to result in improvements in function and quality of life for military members with chronic pain while reducing health care utilization by delivering effective therapies earlier. To be most effective, this work requires a shift away from the unidimensional pain management strategies typically used in primary care (e.g., opioid medication and other analgesics) toward a multifaceted and interdisciplinary pain management strategy focusing on the biopsychosocial factors affecting overall functioning (e.g., beliefs about pain, behaviors that worsen pain, family responses to pain [5]). Such a treatment approach in a primary care environment can target these whole-person factors to increase accessibility and functionality for patients with chronic pain (c.f. [6–8]).

In 2018, the Defense Health Agency (DHA), based in part on the findings from the Army Pain Management Task Force Report [5], published DHA Procedural Instruction (DHAPI) 6025.04, establishing a pain management campaign designed to treat chronic pain by emphasizing nonpharmacological treatments and minimizing the use of opioid medication for chronic pain [9]. DHAPI 6025.04 led to the development of a multicomponent framework for pain management featuring comprehensive assessment and training (see Supplementary Data) and mandated training of a manualized Brief Cognitive Behavioral Therapy for Chronic Pain (BCBT-CP [10, 11]), to be delivered in primary care clinics by integrated primary care behavioral health consultants (BHCs) using a Primary Care Behavioral Health (PCBH) service model (c.f. [12]).

The PCBH service model uses BHCs, who are behavioral health providers (e.g., psychologists, social workers) integrated into primary care teams [12]. The PCBH model has been used widely throughout the country and DOD [13]. All DOD primary care clinics with 3,000 or more enrolled beneficiaries are required to have at least one BHC. Assessments and interventions delivered by BHCs are derived from evidence-based practices (e.g., cognitive behavioral therapy) and are designed to improve functional outcomes for patients with a range of health problems, including chronic pain [14]. Data from our pilot study of the BCBT-CP confirmed short-term, dose-dependent benefits in physical functioning after BCBT-CP treatment (manuscript in preparation [15]). However, longer-term outcomes from pilot-phase testing of BCBT-CP revealed diminished outcomes after 6 months that are consistent with the outcomes after other cognitive behavioral therapies for chronic pain (c.f. [16]). Focus groups with our study participants revealed that they valued the interventions offered by the BHC, but they wanted more contact to address module content and more time to ask questions after beginning home practice (manuscript in preparation). One potential way to improve long-term outcomes of BCBT-CP and meet the expressed needs of patients, without incurring prohibitive amounts of additional staff time or patient appointments, is to use periodic telehealth contacts. Using these contacts improves outcomes after other pain management interventions [17]. Additionally, a few extant studies show promise for telehealth boosters, though there are no published large, pragmatic trials of these contacts.

On the basis of the previous literature, quantitative and experiential data available from our BCBT-CP pilot study (manuscript in preparation), and DHA stakeholder input, we designed a randomized pragmatic trial to test whether the outcomes of BCBT-CP could be improved by augmenting therapy with monthly telehealth contacts. The purpose of the present paper is to describe the methods of the pragmatic trial designed to test this hypothesis.

Methods

Overall Design

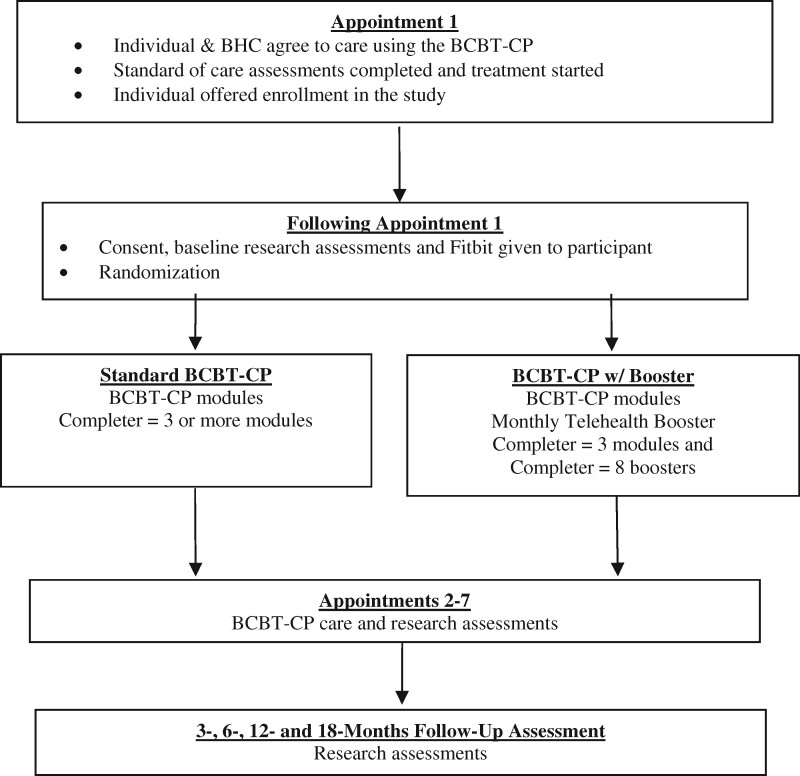

We designed a multisite randomized pragmatic trial. The purpose of this trial is to assess the effect of monthly telehealth booster contacts on long-term BCBT-CP pain outcomes, as compared with BCBT-CP without a booster, in 716 DHA beneficiaries referred to a BHC for chronic pain management. The study is affiliated with the University of Texas Health Science Center at San Antonio-led South Texas Research Organizational Network Guiding Studies on Trauma and Resilience (STRONG STAR) Consortium, a multi-institutional and multidisciplinary research consortium of investigators focused on the diagnosis, treatment, and epidemiology of combat-related posttraumatic stress disorder and comorbid conditions, such as pain. By being affiliated with STRONG STAR, the study is able to employ trained research staff and use standardized procedures for the recruitment, screening, assessment, and monitoring of research participants. The design of the study is summarized in Figure 1. The following aims and hypotheses will be tested.

Figure 1.

Randomized pragmatic trial study design overview. w/= with.

Aim 1: Assess the effect of monthly telehealth booster contacts on long-term BCBT-CP pain outcomes (i.e., Defense and Veterans Pain Rating Scale [DVPRS] score 6, 12, and 18 months after starting treatment) compared with BCBT-CP without a booster in a sample of 716 DHA beneficiaries referred to a BHC for pain management using BCBT-CP. Hypothesis 1: Patients who are randomized to BCBT-CP with monthly telehealth booster contacts will retain a significantly higher proportion of BCBT-CP treatment benefit (defined as the change in DVPRS score from the first to last BCBT-CP module) at 3-, 6-, 12-, and 18-month assessments than that retained by patients randomized to BCBT-CP without booster telehealth contacts.

Aim 2: Assess the effect of monthly telehealth booster contacts on the number of BCBT-CP modules completed by patients referred to the BHC for pain management in a sample of 716 DHA beneficiaries referred to a BHC for pain management using BCBT-CP. Hypothesis 2: Patients randomized to BCBT-CP with monthly telehealth booster contacts will attend significantly more BCBT-CP appointments with the BHC than will those without booster contacts. Qualitative hypothesis 3: We anticipate that patients will identify telehealth booster contacts as acceptable, satisfying, and helpful. Those who complete telehealth booster contacts will be more satisfied with BCBT-CP than those who do not. We will use patient focus groups at the last BCBT-CP module and at 6- and 12-month assessment intervals to assess themes related to satisfaction with BCBT-CP, telehealth booster contacts, understanding of the Military Health System Stepped Care Pain pathway, and understanding of BCBT-CP.

Exploratory aim: Use Fitbit and self-report data to assess the impact of BCBT-CP and BCBT-CP with booster telehealth contact on activity. Exploratory hypothesis: The BCBT-CP is heavily focused on content encouraging increased activity, and we believe that patients who complete BCBT-CP will have higher levels of activity than those who do not (controlling for baseline activity) and that patients who complete BCBT-CP with telehealth booster contacts will demonstrate the highest activity levels.

Although a pragmatic trial should mimic standard practice as much as possible [18], adjunct telehealth booster contacts could be viewed as more “experimental” than “pragmatic” [19]; however, DHA stakeholders conveyed that telehealth contacts to extend and refresh care are a standard part of BHC care. Although the use of scheduled telehealth appointments has significantly increased during the COVID-19 pandemic, BHCs rarely use unscheduled telehealth contacts as an adjunct to treatment (A. Dobmeyer, personal communication, June 20, 2020). Barriers to adjunct telehealth contacts include 1) lack of time in a template scheduled with back-to-back patient appointments, 2) uncertainty about the effectiveness of telephone contacts for treatment extension, and 3) uncertainty about the best content for these contacts. Even if BHCs are not able to create the time to make these calls, many clinics throughout the Military Health System also have Behavioral Health Care Facilitators (BHCFs). The role of the BHCF, which is often filled by a nurse, is to engage with patients to increase the likelihood that they are following treatment plans and helping them to problem-solve barriers to care. Telehealth boosters could easily be completed by BHCFs.

Our team rated this study on the elements of a pragmatic trial using the PRagmatic-Explanatory Continuum Indicator Summary (PRECIS-2) guide [19] available at the website https://www.precis-2.org/. As shown in the Supplementary Data, the PRECIS-2 diagram for our present trial reflects a pragmatic design (note that the location of dots in the figures corresponds to the level of pragmatism). Particular strengths of our pragmatic study include limited changes in standard care practices; a large sample size representative of the population of interest (716 Military Health System beneficiaries across multiple clinics and BHCs); diverse settings (using U.S. Air Force and U.S. Army clinics serving a mix of active duty, veteran, and family member patients; broad inclusion criteria related to pain presentation); and reliance on treatment mechanisms that are already part of standard BHC practice (both BCBT-CP and telehealth booster contacts are trained and encouraged parts of existing BHC practice). As shown in the PRECIS-2 and based on our study design, eligibility, setting, and primary analysis will be highly pragmatic. Recruitment, organization, and flexibility are a little less pragmatic. Because individuals are being contacted by the researchers during and after the intervention, beyond what would typically occur in the clinic, follow-up was considered the least pragmatic aspect of the study. However, patients, DHA stakeholders, and Military Health System clinical stakeholders all confirmed with our team that even before the COVID-19 pandemic, telehealth contacts were a normal part of practice. In response to the restrictions associated with COVID-19, telehealth contacts have become more commonplace and are acceptable to patients.

Study Population

Inclusion criteria for the pragmatic clinical trial are 1) DHA beneficiaries (including active duty service members, veterans, and family members) receiving their primary care at a military treatment facility; 2) age 18 years and older; 3) presenting with a chronic pain complaint (i.e., ongoing pain occurring more days than not over the past 3 months); 4) referred for BCBT-CP with a BHC by a primary care provider; and 5) speaks, reads, and understands English enough to participate in the behavioral intervention and can reliably complete the home practice plans, as well as the study assessment measures. Exclusion criteria include having a planned pain-related surgery or pain intervention within 6 weeks of study enrollment and or having a health problem requiring a higher priority for care, such as active psychosis or suicidal ideation with intent.

Screening, Recruitment, and Randomization Procedures

Patient participants will be screened and recruited from the clinical population of cases referred to BHCs at the participating clinics. All patients with chronic pain who are being seen by a site BHC will be offered the opportunity to participate in the study. BHCs will provide basic information about the study, and if the patient is interested, the patient will be referred to study staff for more information, screening, and consent procedures. Treatment provided to patients will be equivalent, whether they are participating in the study or not. Participants who give consent will be randomly assigned to one of the two study arms, BCBT-CP or BCBT-CP with telehealth booster contacts, at a 1:1 ratio. Randomization will be stratified by clinic so that an equal number of participants at each of the participating clinics are randomized to each condition, and randomization will be done in varying blocks so that the study staff cannot anticipate what the next randomization might be. Patients, as well as primary care clinic providers and staff, will be invited to participate in separate focus groups offered throughout the conduct of the trial. Focus groups for both patients and primary care clinic providers and staff will assess the usability, ease of use, perceived effectiveness, and helpfulness of the BCBT-CP intervention, as well as barriers to its use. In accordance with 24 USC 30 [20], which restricts the use of research incentives for active duty military personnel unless blood is being collected, participants will not be paid either for completing the study surveys or for participating in the focus groups.

Participating Sites

Participants will be recruited at primary care clinics with integrated BHCs at three military installations, two Army and one Air Force, located in south Texas.

Interventions: BCBT-CP

The BCBT-CP includes up to seven 30-minute modules with manualized, nonpharmacological interventions for chronic pain that are suitable for delivery by BHCs working in primary care clinics [10]. It is adapted from an 11-session version of Cognitive Behavioral Therapy for Chronic Pain, which allowed for one optional booster [21, 22]. All BHC BCBT-CP providers are trained through the DHA in a standardized format that includes basic education about chronic pain and pain management, assessment via the DVPRS, and implementation of the BCBT-CP manualized intervention. BHCs are trained through telehealth and attend 10 group consultation meetings during the first 6 months of implementation to monitor and hone their use of BCBT-CP.

The seven BCBT-CP modules include A) assessment, engagement, and goal setting, B) education on chronic pain and relaxation training, C) discussion of the importance of activity engagement and pacing, D) progressive muscle relaxation and guided imagery, E) identifying thoughts that negatively impact pain, F) modifying thoughts that negatively impact pain, and G) developing an action plan. Patients are encouraged to complete a minimum of three modules (A, B, and at least one additional module). Although the recommended latency between BCBT-CP modules is 2 weeks, participants in our pilot study experienced an average of 3 to 4 weeks between modules (manuscript in preparation). Each primary care module appointment lasts approximately 30 minutes and includes the following treatment components: 1) introduction to the module and appointment agenda confirmation; 2) checking on mood and completion of patient measures (i.e., DVPRS [23]); 3) review of material from previous modules, including home practice; 4) introduction of the new material and answering questions; and 5) module wrap-up.

Interventions: BCBT-CP with Telehealth Booster Contacts (BCBT-CP Telehealth Booster)

BCBT-CP telehealth booster contacts are intended to reinforce BCBT-CP content without introducing new skills. We have manualized the booster contacts to reinforce the BCBT-CP content and related home-based practice. Telehealth booster content and the rationale for the component and intervention are summarized in the Supplementary Data. Patients randomized to BCBT-CP with telehealth booster contacts will receive monthly telehealth booster contacts for 12 months, regardless of the number of BHC appointments they attend. The following guidelines will be used to schedule booster contacts: 1) Telehealth booster contacts will occur within 2 weeks after a BCBT-CP module; 2) telehealth booster contacts will continue at least once per month until study participation is complete; and 3) telehealth booster contacts will be delivered by study staff acting to support the patient in BCBT-CP.

These guidelines allow for booster contacts that occur regularly but with sufficient time gaps around BCBT-CP modules to allow for skill refreshment between modules. An example schedule is presented in the Supplementary Data. All booster providers will be trained by the study investigators on understanding chronic pain, treatment for chronic pain, and the DHA Pain Pathway, with a brief introduction to the BCBT-CP manual. Booster providers will also receive an orientation on the conduct of telehealth booster contacts, including a description of how to complete the BCBT-CP booster documentation form. Investigators will consult with booster providers weekly to address questions and concerns about booster administration. After 12 months of booster calls, participants in the BCBT-CP with booster arm will not receive any more calls for the remainder of their 18-month study participation period to assess the durability of treatment outcomes.

Adverse Event Assessment

This study will use the STRONG STAR Consortium standardized adverse event monitoring [24] at all research touchpoints. A member of the research team will ask participants, “Have you had any problems since we last spoke?,” and all reported events that are a change from baseline will be recorded as a possible adverse event and adjudicated during weekly team teleconferences. No BCBT-CP content will be discussed during these calls. In the course of booster contacts, if any patient participant conveys elevated risk (e.g., suicidal ideation), the local clinic’s policies will be followed, informed by the STRONG STAR Consortium standardized operating procedures for managing suicidality. Depending on the level of acuity, the patient could be kept on the line while emergency services are called, or the patient could be encouraged to come into the primary care clinic immediately to speak with a provider. The primary care provider and/or BHC will be notified by the study staff via telephone contact and secure/encrypted messaging of the event, and actions will be taken to follow up with the patient participant.

Baseline and Follow-Up Procedures (Schedule of Assessments)

The baseline assessments, follow-up procedures, and schedule of assessments are outlined in the Supplementary Data.

Primary Outcome

The primary outcome measure is the difference in DVPRS [23] between groups at the 12-month assessment. The DVPRS was developed in response to the 2010 Office of the Army Task Force report as [5] a standardized pain rating scale combining features of numeric, graphic, and written functional word descriptor anchors that is mandated by the DHA as the primary outcome for BCBT-CP in the DHA Stepped Care Pain Pathway. The full DVPRS includes two pain intensity items (current and average in past week) plus four supplemental items, each rated on a 0–10 numeric rating scale, that assess functioning in the context of pain, including interference of pain on general activity, impact of pain on stress, impact of pain on sleep, and impact of pain on mood. The DVPRS assessment was developed in response to concerns raised by Military Health System providers in the Pain Management Task Force report about the limited clinical value of standard numeric rating scales. It has shown good reliability and validity in these populations [23]. Although evidence is growing in support of the psychometric strength of the DVPRS [25], it is still a new measure. Thus, the present study chose to include the Pain Intensity, Enjoyment and General Activity measure (PEG-3) as another primary outcome to help add to the validation of the DVPRS and to lend certainty to clinical change thresholds and power analysis. The PEG-3 [26] is a three-item Likert scale questionnaire that examines pain intensity and pain interference.

Secondary and Exploratory Outcomes

Secondary outcomes relate to our second aim. We will examine additional outcomes using the validated measures listed in the Supplementary Data. Two of these measures are utilized in routine BHC practice. The Behavioral Health Measure (BHM-20) [27] is administered at all Military Health System PCBH patient visits, regardless of presenting problem. This 20-item measure, which is well validated in primary care settings, examines changes in general psychological distress and functioning [28]. Fitbit data include daily steps and daily activity, which will be used as an outcome in exploratory analyses.

Statistical Methods

Generalized linear models will be used to examine the primary and secondary outcomes. Specifically, a generalized linear model will be created to examine the superiority of BCBT-CP with monthly telehealth booster contacts over BCBT-CP alone in reducing pain at follow-up. This model will include baseline pain scores with a fixed effect for treatment group. This is akin to an analysis of covariance (ANCOVA) approach but allows for specification of the outcome distribution by using an appropriate distribution and link function. It is anticipated that a normal distribution with log-link will fit the data well, but a log-link will be examined for improved model fit if the data are skewed. The number of treatment appointments attended will be modeled with a generalized linear model by using a count distribution (e.g., negative binomial) and log-link. Because this is a pragmatic trial, analyses are planned with a sensitivity model that adjusts treatment effects for post-randomization prognostic factors (e.g., affective distress, disability).

Sample Size Determination

Enrolling 358 per group (N = 716) will provide sufficient power to examine both study aims. Specifically, in Aim 1, we assume that the adjusted means in follow-up DVPRS pain scores will differ by 0.65 (standard deviation=3.1) points between treatment groups (on the basis of observed scores from our pilot study). Thus, enrolling 358 participants per arm will provide 80% power to detect this difference, assuming two-tailed alpha=0.05 in a generalized linear model. This sample size will allow power >0.95 for Aim 2, where a difference of 1 treatment appointment (standard deviation=1.7) is expected between randomized groups (again, on the basis of pilot study data). For power analysis, we assumed a small intraclass correlation coefficient value of 0.16 because of geographic and population differences across sites (i.e., some clinics treat active duty patients only, whereas some treat dependents and retirees).

Analytic Methods: Primary Hypothesis

Patients who are randomized to BCBT-CP with monthly telehealth booster contacts will retain a significantly higher amount of BCBT-CP treatment benefit (defined as the change in DVPRS score from the first to last BCBT-CP module) than that retained by patients randomized to BCBT-CP without telehealth booster contacts.

Analytic Methods: Secondary Hypothesis

Patients randomized to BCBT-CP with monthly telehealth booster contacts will attend significantly more BCBT-CP appointments with the BHC than will those without booster contacts. We anticipate that booster patients will attend at least one more appointment than no-booster patients. Patient adherence to pain treatments is directly linked to perceived credibility of the treatment and treatment satisfaction [29]. Thus, we anticipate that booster contacts will have an indirect effect on treatment adherence as a function of improved satisfaction with treatment overall and will directly affect adherence through reminders to increase attendance of subsequent BCBT-CP modules. Our pilot data (manuscript in preparation) revealed a dose-dependent response to BCBT-CP, with patients who attended more modules reporting better outcomes at the 3-month assessment. Thus, increasing module attendance should generate better outcomes. Booster contacts are expected to improve BCBT-CP attendance through refreshing content, improving patient satisfaction, improving home-based practice, and reminding patients about upcoming appointments.

Exploratory Hypothesis

We expect that patients who complete BCBT-CP (i.e., at least 3 BCBT-CP modules) will evidence higher levels of activity than those who do not (controlling for baseline activity) and that patients who complete BCBT-CP with telehealth booster contacts will demonstrate greater activity levels, as measured by Fitbit data and self-report measures. Activity levels will be derived from a subsample of 200 participants wearing Fitbit devices and will be analyzed in a linear mixed-model analysis in which randomization assignment (booster vs no booster) will be a fixed effect and aggregation level of activity (i.e., steps per day) will be a random effect.

Qualitative Analysis

We will assess patient perceptions of the telehealth booster contacts as acceptable, satisfying, and helpful. We expect that those who complete telehealth booster contacts will be more satisfied with BCBT-CP compared to those who did not receive the telehealth booster contacts. We will use patient focus groups to assess themes related to satisfaction and use of BCBT-CP, satisfaction and acceptability of booster contacts, and understanding of BCBT-CP. All participants will be invited to participate in the focus groups. The focus groups will include four to six patient participants, and each session will last approximately 60 minutes. The interview will be audio-taped for transcription and analysis. Several focus groups will be conducted over the course of the study. Data will be analyzed with a Thematic Analysis approach similar to that described by Thompson and colleagues [30].

Procedures for Handling Missing Data

Consistent with recommended pragmatic trial methodology, statistical analysis will be completed as intent-to-treat (ITT [31]). Because of concern about potential bias associated with differentially missing data, research staff will attempt to reach out by telephone to any participant who drops out or withdraws from the study to assess the reason for dropout and the patient’s current pain outcomes (i.e., DVPRS). Missing data will be used with propensity score adjustment to minimize bias in outcome analysis.

Implementation and Dissemination Procedures

The knowledge gained from this study will benefit primary care teams treating patients with chronic pain. Results will indicate whether the BCBT-CP care with booster calls is feasible and effective in clinical settings above and beyond BCBT-CP care without telehealth contact, accounting for real-world implementation. Our plans to disseminate findings are broad and include national conference presentations, journal articles, press outlets, social media, the Pain Management Collaboratory Coordinating Center (PMC3) website, and other avenues generated through collaborations with key stakeholders (e.g., DHA leadership) and PMC working groups. Dissemination of the research findings through manuscripts and presentations to stakeholders and scientists may 1) influence primary care providers to incorporate the PCBH model into their treatment teams and 2) lead to better use of existing primary care staff (e.g., nurses, BHCFs, BHCs) to increase patient functioning, improve pain symptoms, and decrease health care utilization and opioid use among their patients.

Discussion

The design of this study was based on consultation with our DHA and Military Health System stakeholders, lessons learned from our pilot study (manuscript in preparation), and consultation with the PMC3’s biostatistics, phenotype, electronic health record, and dissemination and implementation workgroups. Results will help elucidate the contribution of BHCs to improving the functioning of those with chronic pain and whether extra efforts to provide telephonic booster contacts help patients to further improve functioning. We anticipate that standardized BCBT-CP and booster session training across primary care sites is likely to enhance the consistency of care and treatment messaging around chronic pain, which is especially important given the frequent relocation of military members and their families. These findings will not only be important for contributions to the existing literature, but will also inform the policy and implementation strategies of our DHA and Military Health System stakeholders.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgment

This manuscript is a product of the NIH-DOD-VA Pain Management Collaboratory. For more information about the Collaboratory, visit: http://painmanagementcollaboratory.org.

Supplementary Data

Supplementary Data may be found online at http://painmedicine.oxfordjournals.org.

Funding sources: Research reported in this publication was supported by the National Center for Complementary and Integrative Health of the National Institutes of Health under Award Number U24AT009769. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health.

Conflicts of interest: None to report.

Supplement sponsorship: This article appears as part of the supplement entitled “NIH-DOD-VA Pain Management Collaboratory (PMC)”. This supplement was made possible by Grant Number U24 AT009769 from the National Center for Complementary and Integrative Health (NCCIH), and the Office of Behavioral and Social Sciences Research (OBSSR). Its contents are solely the responsibility of the authors and do not necessarily represent the official views of the NCCIH, OBSSR, and the National Institutes of Health.

Disclosure: The U.S. Army Medical Research Acquisition Activity, 820 Chandler Street, Fort Detrick MD 21702-5014, is the awarding and administering acquisition office. This work was supported by the Assistant Secretary of Defense for Health Affairs endorsed by the Department of Defense, through the Pain Management Collaboratory–Pragmatic Clinical Trials Demonstration Projects under Award No. W81XWH-18-2-0008. Opinions, interpretations, conclusions, and recommendations are those of the authors and are not necessarily endorsed by the Uniformed Services University, the Department of Defense, the Department of Health and Human Services, the Department of Veterans Affairs.

References

- 1. Fortney J, Enderle M, McDougall S, et al. Implementation outcomes of evidence-based quality improvement for depression in VA community based outpatient clinics. Implement Sci 2012;7(1):1–15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. McGeary DD, Seech T, Peterson AL, et al. Health care utilization after interdisciplinary chronic pain treatment: Part I. Description of utilization of costly health care interventions. J Appl Biobehav Res 2012;17(4):215–28. [Google Scholar]

- 3. Jamison RN, Sheehan KA, Scanlan E, Matthews M, Ross EL. Beliefs and attitudes about opioid prescribing and chronic pain management: Survey of primary care providers. J Opioid Manag 2014;10(6):375–82. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Alford DP. Opioid prescribing for chronic pain—Achieving the right balance through education. N Engl J Med 2016;374(4):301–3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Office of the Army Surgeon General (OTSG). Pain Management Task Force Report: Providing a Standardized DoD and VHA Vision and Approach to Pain Management to Optimize the Care for Warriors and Their Families. 2010. Available at: https://armymedicine.health.mil/Regional-Health-Commands/Office-of-the-Surgeon-General/R2D/Pain-Management.

- 6. Gatchel RJ, McGeary DD, McGeary CA, Lippe B. Interdisciplinary chronic pain management: Past, present, and future. Am Psychol 2014;69(2):119–30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Pincus T, Kent P, Bronfort G, et al. Twenty-five years with the biopsychosocial model of low back pain-is it time to celebrate? A report from the twelfth international forum for primary care research on low back pain. Spine 2013;38(24):2118–23. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Seal K, Becker W, Tighe J, Li Y, Rife T. Managing chronic pain in primary care: It really does take a village. J Gen Intern Med 2017;32(8):931–4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Defense Health Agency (DHA). Pain Management and Opioid Safety in the Military Health System (MHS) 6025.04. 2018.

- 10. Beehler GP, Murphy JL, King PR, Dollar KM, et al. Brief cognitive behavioral therapy for chronic pain: Results from a clinical demonstration project in primary care behavioral health. Clin J Pain 2019;35(10):809–17. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Beehler GP, Dobmeyer AC, Hunter CL, Funderburk JS. Brief Cognitive Behavioral Therapy for Chronic Pain: BHC Manual . Silver Spring, MD: Defense Health Agency; 2018. [Google Scholar]

- 12. Reiter JT, Dobmeyer AC, Hunter CL. The Primary Care Behavioral Health (PCBH) Model: An overview and operational definition. J Clin Psychol Med Settings 2018;25(2):109–26. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Hunter CL, Goodie JL, Dobmeyer AC, Dorrance KA. Tipping points in the Department of Defense's experience with psychologists in primary care. Am Psychol 2014;69(4):388–98. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Hunter CL, Goodie JL, Oordt MS, Dobmeyer AC. Integrated Behavioral Health in Primary Care: Step-By-Step Guidance for Assessment and Intervention, 2nd edition. Washington, DC: American Psychological Association; 2017. [Google Scholar]

- 15. Kanzler KE, McGeary DE, McGeary C, et al. Conducting a pragmatic trial in integrated primary care: Key decision-points and considerations. Under review. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 16. Ehde DM, Dillworth TM, Turner JA. Cognitive-behavioral therapy for individuals with chronic pain: Efficacy, innovations, and directions for research. Am Psychol 2014;69(2):153–66. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. McGeary DD, Peterson AL, Seech T, et al. Health care utilization after interdisciplinary chronic pain treatment: Part II. Preliminary examination of mediating and moderating factors in the use of costly health care procedures. J Appl Biobehav Res 2013;18(1):24–36. [Google Scholar]

- 18. Dal-Re R, Janiaud P, Ioannidis JPA. Real-world evidence: How pragmatic are randomized controlled trials labeled as pragmatic? BMC Med 2018;16(1):49. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Loudon K, Treweek S, Sullivan F, et al. The PRECIS-2 tool: Designing trials that are fit for purpose. BMJ 2015;350(may08 1):h2147. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hospitals and Asylums 24 USC §30. 2011. Available at:https://www.govinfo.gov/content/pkg/USCODE-2011-title24/html/USCODE-2011-title24.htm (accessed October 6, 2020). [Google Scholar]

- 21. Stewart MO, Karlin BE, Murphy JL, et al. National dissemination of cognitive-behavioral therapy for chronic pain in veterans: Therapist and patient-level outcomes. Clin J Pain 2015;31(8):722–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Murphy JL, McKellar JD, Raffa SD, et al. Cognitive Behavioral Therapy for Chronic Pain Among Veterans: Therapist Manual. Washington, DC: US Department of Veterans Affairs; 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 23. Buckenmaier IICC, Galloway KT, Polomano RC, et al. Preliminary validation of the Defense and Veterans Pain Rating Scale (DVPRS) in a military population. Pain Med 2013;14(1):110–23. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Peterson AL, Roache JD, Raj J, Young-McCaughan S, STRONG STAR Consortium. The need for expanded monitoring of adverse events in behavioral health clinical trials. Contemp Clin Trials 2013;34(1):152–4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Polomano RC, Galloway KT, Kent ML, et al. Psychometric testing of the Defense and Veterans Pain Rating Scale (DVPRS): A new pain scale for military population. Pain Med 2016;17(8):1505–19. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Krebs EE, Lorenz KA, Bair MJ, et al. Development and initial validation of the PEG, a three-item scale assessing pain intensity and interference. J Gen Intern Med 2009;24(6):733–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Kopta SM, Lowry JL. Psychometric evaluation of the Behavioral Health Questionnaire-20: A brief instrument for assessing global mental health and the three phases of psychotherapy outcome. Psychother Res 2002;12(4):413–26. [Google Scholar]

- 28. Bryan CJ, Blount T, Kanzler KA, et al. Reliability and normative data for the Behavioral Health Measure (BHM) in primary care behavioral health settings. Fam Syst Health 2014;32(1):89–100. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Timmerman L, Stronks DL, Huygen FJ. The relation between patients’ beliefs about pain medication, medication adherence, and treatment outcome in chronic pain patients: A prospective study. Clin J Pain 2019;35(12):941–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Thompson M, Vowles K, Sowden G, Ashworth J, Levell J. A qualitative analysis of patient‐identified adaptive behaviour changes following interdisciplinary Acceptance and Commitment Therapy for chronic pain. Eu J Pain 2018;22(5):989. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Gamerman V, Cai T, Elsäßer A. Pragmatic randomized clinical trials: Best practices and statistical guidance. Health Serv Outcomes Res Methodol 2019;19(1):23–35. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.