Abstract

Background:

Four prescription drugs (donepezil, galantamine, memantine, and rivastigmine) are approved by the US FDA to treat symptoms of Alzheimer’s disease (AD). Even modest effectiveness could potentially reduce the population-level burden of AD and related dementias (ADRD), especially for women and racial/ethnic minorities who have higher incidence of ADRD.

Objective:

Describe the prevalence of antidementia drug use and timing of initiation relative to ADRD diagnosis among a nationally representative group of older Americans, and if there are disparities in prevalence and timing by sex and race/ethnicity.

Methods:

Descriptive analyses and logistic regressions of Medicare claims (2008–2016) for beneficiaries who had an ADRD or dementia-related symptom diagnosis, or use of an FDA approved drug for AD. We investigate prevalence of use and timing of treatment initiation relative to ADRD diagnosis across time and beneficiary characteristics (age, sex, race/ethnicity, socioeconomic status, comorbidities).

Results:

Among persons diagnosed with ADRD or related symptoms, 33.3% used an approved drug over the study period. Odds of use was higher among Whites than non-Whites. Among ADRD drug users, 40% initiated use within 6 months of the initial ADRD or related symptoms diagnosis, and 16% initiated prior to a diagnosis. We observed disparities by race/ethnicity: 28% of Asians, 24% of Hispanics, 16% of Blacks, and 15% of Whites initiated prior to diagnosis.

Conclusions:

The use of antidementia drugs is relatively low and varies widely by race/ethnicity. Heterogeneity in timing of initiation and use may affect health and cost outcomes, but these effects merit further study.

Keywords: Acetylcholinesterase inhibitors, Alzheimer’s disease and related dementias, disparities, donepezil, galantamine, memantine, rivastigmine

INTRODUCTION

Alzheimer’s disease and related dementias (ADRD) have a large, growing, and disparate burden on the afflicted individuals, their caregivers, and the health system as a whole. In the United States, there are approximately 7 million individuals aged 65 and older living with ADRD, and this number is projected to grow to 12 million by 2040 [1]. While there are no drugs that can stop or reverse the progression of dementia, four FDA-approved molecules and five marketed products are currently indicated for treatment of Alzheimer’s disease (AD) [2]. These are acetylcholinesterase inhibitors (AChEIs: donepezil, galantamine, and rivastigmine) and memantine, which have shown modest effectiveness in reducing the symptoms of AD [2].

Treatment with antidementia drugs may help delay cognitive decline and maintain daily functioning in some patients, with some evidence showing benefits for functional decline, neuropsychiatric symptoms, nursing home placement, and cognition [3–13]. Other evidence shows a lack of effects for the aforementioned outcomes, and no evidence supports long term benefits [3, 10, 14]. When effective, however, even short-term gains in these outcomes could improve both patient and caregiver quality of life, by possibly delaying the need for a higher level of care. The burden of ADRD care is substantial, estimated at $290 billion in 2019 [2]. This motivated the passage of the National Alzheimer’s Project Act (NAPA), which calls for research identifying interventions that preserve normal neural function, reduce symptoms, and maintain independent functioning for AD patients as long as possible [15].

Despite mixed evidence of effectiveness of AChEIs and memantine, the potential for improved quality of life for patients and caregivers has led these drugs to be recommended in guidelines for AD treatment (AChEIs for mild to moderate disease, and memantine for moderate to severe disease). They are not indicated for non-AD dementia (except rivastigmine for Parkinson’s disease) or mild cognitive impairment [3, 16]. Accordingly, much of the existing evidence on prevalence of use for these drugs focuses on individuals with AD [17–21]. However, some studies suggest that off-label use of antidementia medications is common [22, 23], and focusing strictly on beneficiaries with AD ignores the difficulties of distinguishing etiologic subtypes of dementia and prevalence of mixed dementias. Indeed, etiologic subtype at diagnosis is often unspecified and diagnoses change over time [24], which suggests that it is important to include a broader set of diagnoses (i.e., ADRD and related symptoms) when assessing antidementia treatment in order capture all potential patients. A few studies have examined likelihood of initiation [25], likelihood of use [26], and patient and setting characteristics [27] in this broader set of diagnoses, but a comprehensive picture of contemporary use and users is critically lacking. Furthermore, limited research has examined the extent to which treatment patterns vary across patient sex and race/ethnicity [20, 21, 26]. A notable exception is a study which found that among a representative sample of possible AD drug users, Hispanics were more likely to initiate AChEIs and memantine than Black and White beneficiaries [25]. Research on disparities in use of antidementia medications is particularly germane, given the higher incidence of ADRD and significant burden of ADRD-related care for women and racial and ethnic minorities [28–30].

This paper addresses these gaps by examining treatment patterns of AChEIs and memantine across sex and race/ethnicity in a nationally representative sample of older adults enrolled in Medicare from 2008–2016. These data provide a comprehensive view of recent use of antidementia drugs by older Americans and include a broad set of demographic characteristics and diagnostic history that can be leveraged to identify the timing of diagnosis and treatment in diverse sub-groups. Given the uncertainty faced by physicians in distinguishing between dementia subtypes, one of our objectives was to evaluate the prevalence of use of antidementia drugs for a broad set of ADRD-related diagnoses, including relevant symptoms; to our knowledge, this is the first study to do so. We also examined the timing of treatment initiation, and variations in use of antidementia drugs over time and by sex and race/ethnicity. A better understanding of disparities in ADRD care is critical to improving care practices and working toward reducing the burden of ADRD, especially for patient sub-groups most at risk.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Data and study population

We used claims data from a random 20% sample of Medicare beneficiaries to examine the utilization of four antidementia drugs (donepezil, galantamine, rivastigmine, and memantine) in the years 2008–2016. The branded version of the combination donepezil and memantine (Namzaric), was only introduced in 2015 and was not included. The analytic samples varied for our different analyses; all were composed of individuals who either used one of the four drugs, or received a diagnosis related to ADRD (specified below). In each year of observation t, we required that the individuals be enrolled in fee-for-service (FFS) Medicare and Part D for three consecutive years (years t-2, t-1, and t). This ensures observation of any relevant diagnoses and all prescription drug utilization for each individual. When describing users of the drugs, we required a minimum amount of use of one of the four drugs (specified below). In analyses of medication use among individuals with a diagnosis, we required individuals to have a diagnosis of AD, non-AD dementia, and/or dementia-related symptoms (defined below). Additionally, in analyses that evaluate drug initiation timing, we required the presence of both a diagnosis and a drug claim, and at least 36 months of observability after the earlier of these two events. This restriction ensures that no one was censored through death or attrition during the observation period; in doing so, it removes individuals who die within 36 months of an ADRD diagnosis. The study was approved by the University of Southern California Institutional Review Board.

Measures and outcomes

Main outcomes were the percent of diagnosed individuals using each of the four antidementia drugs, and the timing of initiation relative to dementia-related diagnoses as determined by ICD-9 (International Classification of Diseases) or ICD-10 codes. The diagnoses of interest were AD, non-AD dementia, and a set of dementia-related symptoms (amnesia, aphasia, other symbolic dysfunctions, apraxia, agnosia, and mild cognitive impairment) (Supplementary Material). These symptoms were included because the four drugs are sometimes prescribed for patients exhibiting them [22], and they represent a set of symptoms that occur even in the early stages of cognitive impairment [31–33]. Prescribing AChEIs and memantine for dementia-related symptoms may reflect the difficulties of establishing a definitive diagnosis, which can sometimes require multiple encounters between a physician and patient [24].

Antidementia drug use was first defined as at least seven possession days and one claim within a calendar year. Drugs were identified using the National Drug Code (NDC) associated with each drug on a Part D claim. Seven days was chosen as a minimum threshold in order to capture nearly all users of the drugs, including those who only used for a short period. Secondary definitions required higher adherence thresholds (90, 180, and 270 possession days, along with 2 claims) to be considered a medication user; non-adherence to treatment is often a barrier to effective therapy in AD [34], and these thresholds reflect levels of adherence that may provide better effectiveness. Combination use on the same day (e.g., possessing both memantine and an AChEI on the same day) was only counted as a single possession day. We also examined total possession days per year for each of the drugs, and initiation of use, defined as an antidementia drug claim with no prior observed use.

The investigation included characteristics of AChEI and memantine use (possession days, timing of initiation, drug name, prescribing physician, out-of-pocket cost), and characteristics of the medication users (sex, race/ethnicity, age, socioeconomic status [dual eligibility and low-income subsidy status], and comorbidities ever diagnosed). Dementia specialists were defined as neurologists, psychiatrists, geriatricians, neuropsychiatrists, and geriatric psychiatrists. Race/ethnicity was determined using the beneficiary race code in CMS enrollment data and with the application of a name-based identification algorithm from the Research Triangle Institute [35]. The comorbidity index used was the Centers for Medicaid and Medicare Services-Hierarchical Condition Category (CMS-HCC), an index based on health status from diagnostic data and demographics, in which higher numbers indicate worse health [36].

Statistical analyses

We examined the proportion of individuals diagnosed with ADRD or related symptoms who had ever used antidementia drugs, across sex and race/ethnicity, and calculated descriptive statistics (means and percentages) for the characteristics of drug use. This included details on the timing of their drug initiation, relative to different types of dementia-related diagnoses. We summarized the distribution of the length of time between diagnosis and drug initiation in six-month intervals, with negative values for this length of time corresponding to initiations that preceded diagnoses; we compared this distribution across race and ethnicity. These analyses used a sample restricted to individuals with both a diagnosis and drug use, with full observability for at least 36 months after the earlier of their index diagnosis and drug initiation.

We performed person-year level logistic regressions to determine the degree to which sex and race/ethnicity are associated with AChEI or memantine use among diagnosed individuals, while adjusting for other beneficiary and setting characteristics. We tested four binary dependent variables (measures of drug use), defined by four adherence thresholds of AChEI or memantine use within a year: 7 possession days and 1 claim, 90 days and 2 claims, 180 days and 2 claims, and 270 days and 2 claims. These regressions used clustered standard errors at the beneficiary zip code level, and regressed an indicator for AChEI or memantine use within the year on the following independent variables: sex, age, age squared, race/ethnicity, AD diagnosis, non-AD dementia diagnosis, HCC comorbidity index quartile indicators, dual eligible indicator, low-income subsidy indicator, year fixed effects (2008–2016), outpatient physician utilization (quartiles of number of visits per year), an indicator having seen a dementia specialist physician (neurologists, psychiatrists, geriatricians, neuropsychiatrists, and geriatric psychiatrists), months since diagnosis, and comorbidity indicators for conditions that may be related to the prescribing of AChEIs and memantine (chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, asthma, chronic kidney disease, hypertension, heart failure, glaucoma, acute myocardial infarction, atrial fibrillation, and ischemic heart disease).

RESULTS

Sample description and prevalence of antidementia drug use

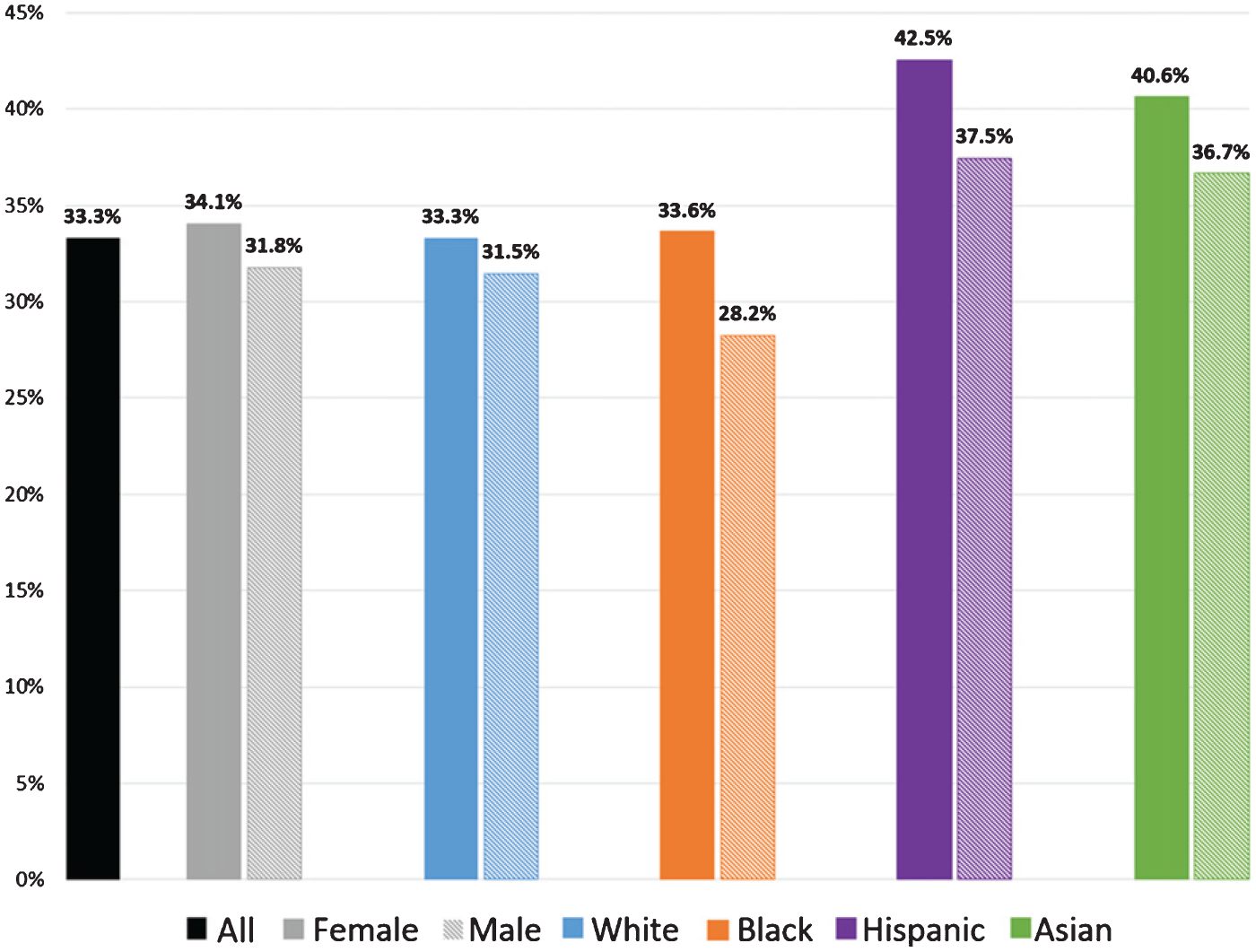

Table 1 describes the sample of individuals with use of an antidementia drug, or a diagnosis for ADRD or dementia-related symptoms during 2008–2016, according to their demographic characteristics, health care utilization, dementia-related diagnoses, antidementia drug use, and comorbidities. Figure 1 displays the unadjusted use rates of AChEIs or memantine, by sex and race/ethnicity for those with a diagnosis of ADRD or dementia-related symptoms before 2016. Among these individuals, 33.3% used any of the four drugs in 2008–2016. The unadjusted rates of drug use were highest for Hispanics (females 42.5%, males 37.5%), followed by Asians (females 40.6%, males 36.7%). White and Black females had similar use rates (White females 33.3%, Black females 33.6%), but White males were more likely to use (31.5%) than Black males (28.2%). While prevalence of use among the diagnosed remained mostly stable during the study period, rates of initiation in the six months following diagnosis declined from 21.0% in 2008 to 15.6% in 2016 (Supplementary Table 1).

Table 1.

Sample description of individuals with use of an antidementia drug, or a diagnosis of AD, non-AD dementia, or dementia-related symptoms (2008–2016)

| N | 721,878 |

|---|---|

| Patient Characteristics | |

| Female (N, %) | 477,641 (66.2%) |

| Age at index date (mean, SD) | 80.40 (7.77) |

| White (N, %) | 600,358 (83.2%) |

| Black (N, %) | 57,412 (8.0%) |

| Hispanic (N, %) | 44,082(6.1%) |

| Asian (N, %) | 20,026 (2.8%) |

| Dual eligible (N, %) | 225,783 (31.3%) |

| Low income subsidy (N, %) | 35,593 (4.9%) |

| Physician visits in year of index date (mean, SD) | 10.09 (8.95) |

| HCC (mean, SD) | 1.90(1.47) |

| Ever saw a specialist (N, %) | 255,213 (36.5%) |

| Dementia-related diagnoses (N, %) | |

| Alzheimer’s disease | 197,561 (27.4%) |

| Non-AD dementia | 514,633 (71.3%) |

| Dementia-related symptoms | 420,987 (58.3%) |

| Used antidementia drug without diagnosis | 11,558 (1.6%) |

| Antidementia drug use (N, %) | |

| Any AChEI | 208,731 (28.9%) |

| Any AChEI & Memantine | 70,880 (9.8%) |

| Donepezil | 187,076 (25.9%) |

| Galantamine | 6,059 (0.8%) |

| Memantine | 99,556 (13.8%) |

| Rivastigmine | 42,484 (5.9%) |

| Comorbidities, ever diagnosed (N, %) | |

| Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease | 341,695 (47.3%) |

| Asthma | 166,987 (23.1%) |

| Chronic kidney disease | 407,612 (56.5%) |

| Hypertension | 686,880 (95.2%) |

| Heart failure | 422,864 (58.6%) |

| Glaucoma | 229,025 (31.7%) |

| Acute myocardial infarction | 90,192(12.5%) |

| Atrial fibrillation | 246,688 (34.2%) |

| Ischemic heart disease | 535,606 (74.2%) |

2008–2016 Medicare claims data (20% sample) for individuals aged 67+, with 3 consecutive years of enrollment in fee-for-service and Part D. Drug use defined as at least 7 days and 1 claim for any of the 4 AD drugs [3 AChEIs (donepezil, galantamine, rivastigmine) and memantine]. Index date is first diagnosis, or first antidementia drug use. AD, Alzheimer’s disease; AChEI, acetylcholinesterase inhibitor; ADRD, AD and related dementias; HCC, hierarchical condition category; dx, diagnosis. Dementia-related symptoms are amnesia, aphasia, other symbolic dysfunctions, apraxia, agnosia, and mild cognitive impairment.

Fig. 1.

Percent using an antidementia drug, among individuals diagnosed with Alzheimer’s disease, non-AD dementia, or dementia-related symptoms, by sex and race/ethnicity. 2008–2016 Medicare claims data (20% sample) for 613,970 individuals aged 67+, with 3 consecutive years of enrollment in fee-for-service and Part D, and one of the diagnoses before 2016. Drug use defined as at least 7 days and 1 claim for any of the 4 AD drugs (3 AChEIs (donepezil, galantamine, rivastigmine) and memantine). AD, Alzheimer’s disease; AChEI, acetylcholinesterase inhibitor; ADRD, AD and related dementias. Dementia-related symptoms are amnesia, aphasia, other symbolic dysfunctions, apraxia, agnosia, and mild cognitive impairment.

Antidementia drug initiation timing

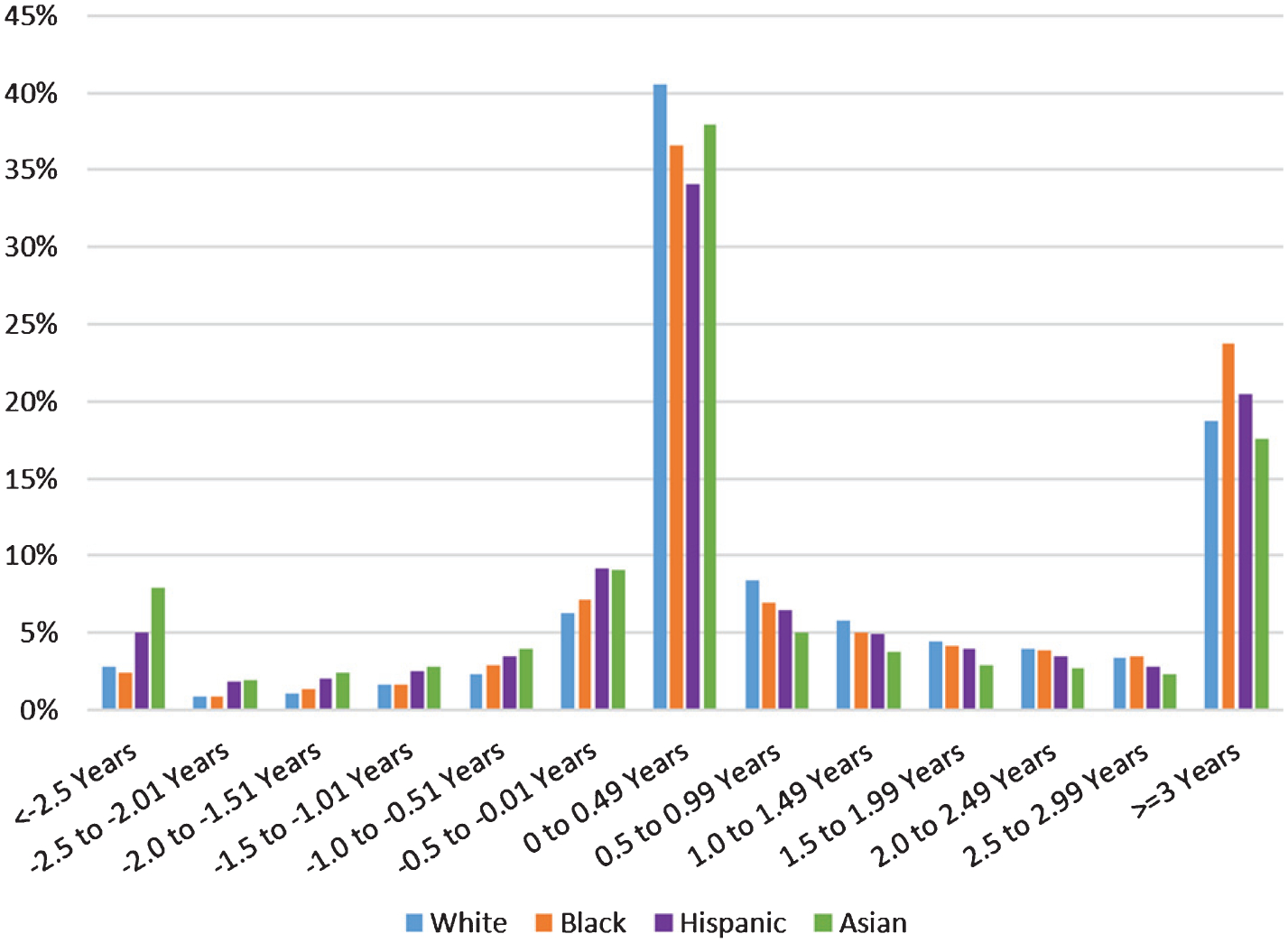

We investigated the length of time between index diagnosis date and drug initiation date among individuals with both a diagnosis and antidementia medication use; values less than zero correspond to drug use that began prior to a diagnosis. Figure 2 shows the distribution of this timing by race/ethnicity relative to the date of the first diagnosis of ADRD or dementia-related symptoms. Forty percent of antidementia drug initiations occurred in the six months after their initial diagnosis, and 16% initiated treatment prior to diagnosis (as represented by the sum of the bars to the left of 0 on the horizontal axis in Fig. 2). More specifically, 3.1% initiated more than 2.5 years prior to a diagnosis, and 22% initiated drug use at least 2.5 years after diagnosis.

Fig. 2.

Timing of antidementia drug initiation, relative to date of ADRD or dementia-related symptom diagnosis, among individuals with both a diagnosis and medication use. 2008–2016 Medicare claims data (20% sample) for 73,161 individuals with an observed index diagnosis, and observed drug initiation for at least 1 of the 4 AD drugs (3 AChEIs (donepezil, galantamine, rivastigmine) and memantine). We require at least 36 months of observation from the index diagnosis or drug initiation, whichever came first, and that individuals are aged 67+, with 3 consecutive years of enrollment in fee-for-service and Part D. AD, Alzheimer’s disease; AChEI, acetylcholinesterase inhibitor; ADRD, AD and related dementias. Dementia symptoms are amnesia, aphasia, other symbolic dysfunctions, apraxia, agnosia, and mild cognitive impairment.

Initiation rates within six months after diagnosis varied across race/ethnicity groups (41% for Whites, 37% for Blacks, 34% for Hispanics, and 38% for Asians). There was a large disparity in the rates of drug use by undiagnosed individuals. Figure 2 shows that 28% of Asians and 24% of Hispanics initiated their drug use before any diagnosis of any type, as compared to 16% of Blacks and 15% of Whites (all differences statistically significant). A similar disparity existed for very early pre-diagnosis use: 2% of Blacks and 3% of Whites initiated drug use at least 2.5 years before their first dementia-related diagnosis of any type; the rate was 5% for Hispanics and 8% for Asians.

Association of antidementia drug use and patient characteristics

Table 2 presents the results from person-year level logistic regressions that identify the association between use of one of the four drugs within a year and sex and race/ethnicity, adjusted for beneficiary and setting characteristics, among individuals with an ADRD or dementia-related symptom diagnosis. Females had similar odds of antidementia drug use to males (odds ratio (OR) = 0.98, 95% confidence interval (CI) = 0.97–0.99)). Compared to White beneficiaries, Black and Asian individuals were significantly less likely to use antidementia drugs at all adherence thresholds, with greater disparities at greater adherence thresholds (p < 0.001). Hispanic individuals were less likely to use antidementia drugs at higher adherence thresholds. For example, the OR for the association between 7 days/1 claim of use and beneficiary race/ethnicity was 0.90 for Blacks and 0.92 for Asians (compared to the reference group, White); the OR for the association between 270 days/2 claims of use and beneficiary race/ethnicity was 0.78 for Blacks, 0.79 for Hispanics, and 0.79 for Asians. In sensitivity analyses, we restricted the sample for the same logistic regressions to individuals who had been diagnosed with ADRD (Supplementary Table 2) and AD (Supplementary Table 3). These results show no meaningful differences from those depicted in the main analyses (Table 2).

Table 2.

Association between antidementia drug use and patient characteristics, among individuals diagnosed with AD, non-AD dementia, or dementia-related symptoms

| Use threshold for dependent variable | 7 days & 1 claim | 90 days & 2 claims | 180 days & 2 claims | 270 days & 2 claims |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Female | 0.98 (0.97–0.99) |

1.00 (0.99–1.01) |

1.01 (1.00–1.02) |

1.02 (1.01–1.03) |

| White (reference) | – | – | – | – |

| Black | 0.90 (0.89–0.92) | 0.86 (0.85–0.88) | 0.83 (0.82–0.85) | 0.78 (0.77–0.82) |

| Hispanic | 0.98 (0.94–1.01) | 0.91 (0.88–0.94) | 0.86 (0.83–0.89) | 0.79 (0.77–0.82) |

| Asian | 0.92 (0.89–0.95) | 0.86 (0.83–0.89) | 0.83 (0.80–0.86) | 0.79 (0.77–0.82) |

| Comorbidity quartile 1 (reference) | – | – | – | – |

| Comorbidity quartile 2 | 0.83 (0.82–0.84) | 0.77 (0.77–0.78) | 0.71 (0.71–0.72) | 0.68 (0.67–0.69) |

| Comorbidity quartile 3 | 0.83 (0.82–0.84) | 0.80(0.79–0.81) | 0.76 (0.76–0.77) | 0.73 (0.72–0.74) |

| Comorbidity quartile 4 | 0.78 (0.77–0.79) | 0.80(0.80–0.81) | 0.82(0.81–0.83) | 0.76 (0.75–0.77) |

| Dual eligible | 1.10(1.08–1.11) | 1.15 (1.14–1.16) | 1.17 (1.15–1.18) | 1.22(1.21–1.24) |

| Low-income subsidy | 1.02(1.00–1.04) | 1.01 (0.98–1.03) | 0.99 (0.97–1.02) | 0.98 (0.95–1.00) |

| N meeting use threshold | 1,379,112 | 1,154,673 | 968,857 | 746,794 |

Odds ratios and 95% confidence intervals from logistic regressions of 4,685,826 person-years (1,403,076 unique beneficiaries) with indicator dependent variable for if the individual used one of the four AD drugs (donepezil, galantamine, rivastigmine, and memantine) in that year. Drug use defined in column title. Sample is person-years of Medicare beneficiaries in the years t = 2008–2016 with a diagnosis of Alzheimer’s disease (AD), non-AD dementia, or dementia-related symptoms (amnesia, aphasia, other symbolic dysfunctions, apraxia, agnosia, and mild cognitive impairment). Sample restricted to those aged 67+, with 3 consecutive years of enrollment in fee-for-service and Part D. All regressions feature controls for age, age squared, comorbidity index quartiles, AD diagnosis, non-AD dementia diagnosis, socioeconomic status, year fixed effects, physician utilization, dementia specialist utilization, months since diagnosis, comorbidity indicators (chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, asthma, chronic kidney disease, hypertension, heart failure, glaucoma, acute myocardial infarction, atrial fibrillation, and ischemic heart disease). Standard errors clustered at zip code level.

Individuals with a higher comorbidity index were less likely to use drugs than those with lower values. For example, the OR of the association between 7 days/1 claim of use was 0.83 (CI = 0.82–0.84) for the second quartile of the index, 0.83 (CI = 0.82–0.84) for the third quartile, and 0.78 (0.77–0.79) for the fourth quartile, as compared to individuals in the first quartile (the healthiest). Dual eligible individuals were more likely to use antidementia drugs, especially at higher levels of adherence (270 days/2 claims OR = 1.22, CI = 1.21–1.24).

Antidementia drug use across time

Table 3 displays trends in the characteristics of medication users in 2008, 2010, 2012, 2014, and 2016, including persons both with and without a diagnosis. Odd years are omitted for space, but they matched the trends in the neighboring even years. Donepezil was by far the most common drug (69–72% of users), followed by memantine (45–48%), rivastigmine (12–16%), and galantamine (2–7%). Among users, 30–34% used both an AChEI and memantine in combination. Across time, the relative prevalence of each drug was mostly stable, except a decline in the use of galantamine. The mean out-of-pocket cost for a 30 day supplies of the drugs ranged from $30–39 in 2008 to $4–34 in 2016, partially reflecting the timing of generic availability (donepezil (Aricept) 2011, galantamine (Razadyne) 2008, rivastigmine (Exelon) 2007, memantine (Namenda) 2010) [37]. The mean number of possession days increased from 233 to 241 per year across the entire study period.

Table 3.

Trends in antidementia drug use, irrespective of diagnosis, 2008–2016

| 2008 | 2010 | 2012 | 2014 | 2016 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total antidementia drug users | 155,498 | 158,584 | 158,961 | 155,995 | 164,580 |

| Any AChEI | 87% | 87% | 86% | 85% | 84% |

| Any AChEI & memantine | 32% | 34% | 33% | 32% | 30% |

| Donepezil | 72% | 70% | 69% | 69% | 72% |

| Galantamine | 7% | 4% | 3% | 3% | 2% |

| Memantine | 45% | 48% | 47% | 47% | 46% |

| Rivastigmine | 12% | 16% | 16% | 16% | 12% |

| Out of pocket costs (mean, 30-day supply) | |||||

| Donepezil | $30 | $36 | $6 | $4 | $4 |

| Galantamine | $37 | $22 | $19 | $19 | $18 |

| Memantine | $31 | $33 | $27 | $33 | $24 |

| Rivastigmine | $39 | $40 | $33 | $36 | $34 |

| Patient characteristics | |||||

| Female | 73% | 73% | 71% | 69% | 66% |

| White | 81% | 79% | 79% | 80% | 83% |

| Black | 10% | 9% | 10% | 9% | 8% |

| Hispanic | 7% | 8% | 9% | 8% | 6% |

| Asian | 2% | 3% | 3% | 3% | 3% |

| No dementia diagnosis or related symptoms | 5% | 4% | 3% | 3% | 2% |

| HCC (mean) | 1.67 | 1.65 | 1.67 | 1.55 | 1.45 |

| Use characteristics | |||||

| Initially prescribed by dementia specialist | 21% | 22% | 24% | 27% | 29% |

| Possession days per year (mean) | 233 | 238 | 243 | 242 | 241 |

| Still using 12–24 months after initiation* | 76% | 73% | 74% | 70% | - |

| Age at initiation (mean) | 82.3 | 82.0 | 81.5 | 81.1 | 80.8 |

Medicare claims data (20% sample) for individuals aged 67+, with 3 consecutive years of enrollment in fee-for-service and Part D. Drug use defined as at least 7 days and 1 claim for any of the 4 AD drugs (3 AChEIs (donepezil, galantamine, rivastigmine) and memantine). The sample is prevalent users in the column year. Odd years omitted for space. Dementia specialists are neurologists, psychiatrists, geriatricians, neuropsychiatrists, and geriatric psychiatrists.

Calculation of percent still using 12–24 months after initiation is restricted to individuals who survive 24 months (not observable in 2016). AD, Alzheimer’s disease; AChEI, acetylcholinesterase inhibitor; ADRD, AD and related dementias), HCC, hierarchical condition category. Dementia-related symptoms are amnesia, aphasia, other symbolic dysfunctions, apraxia, agnosia, and mild cognitive impairment.

A small portion of users had received no diagnosis for any type of dementia, or any dementia-related symptom, despite receiving an antidementia drug (2–5% of users). This group became smaller over time but remained 2.3% of users in 2016 (representing approximately 19,000 individuals in the continuously enrolled Medicare Part D population). While the racial/ethnic composition was relatively stable across time, users were healthier in 2016 than earlier, with their mean HCC comorbidity index declining from 1.67 to 1.45, and mean age of initiation declining from 82.3 in 2008 to 80.8 in 2016. Over the same years, the portion of initiations that were prescribed by a specialist increased from 21% to 29%.

DISCUSSION

In this study, we examined Medicare FFS and Part D drug claims for the four drugs currently approved for the treatment of AD (donepezil, galantamine, rivastigmine, and memantine) from 2008–2016. We examined the factors associated with use versus non-use among individuals with ADRD or a dementia-related diagnosis, as well as characteristics of the medication users. We found that approximately one-third of beneficiaries diagnosed with ADRD or dementia-related symptoms used at least one of the drugs. After adjusting for beneficiary and setting characteristics, use of antidementia drugs was more common for White individuals than for Black and Asian individuals at all adherence levels, and also more common than for Hispanic individuals at higher levels of adherence. Beneficiaries with greater comorbidity were less likely to use drugs, and individuals with dual eligibility (Medicare and Medicaid) were more likely. Only 40% of users initiated therapy in the six months following diagnosis; 44% initiated later, and 16% initiated use before their first diagnosis. Pre-diagnosis initiation was much more common for Asians and Hispanics than for Blacks and Whites. Among diagnosed individuals, prevalence of use remained stable from 2008–2016, despite declines in out-of-pocket costs, and initiation rates declined.

Our findings show that use of AChEIs and memantine is relatively low in a population of older adults who were diagnosed with ADRD or dementia-related symptoms. While these drugs are only indicated for AD (except for rivastigmine for Parkinson’s disease), recent work suggests that dementia etiological subtype at initial diagnosis is often unspecified, due to etiologic uncertainty at that time, and also that the diagnosis subtype changes over time [2, 24]. This lack of diagnostic certainty across dementia subtypes and potential underdiagnosis of AD suggest that some individuals with claims for non-AD dementia and dementia-related symptoms, who may actually have AD, may possibly receive some benefits from use of these drugs, including delayed functional decline. While the effects of the drugs might be modest, even small delays in loss of cognition and functional decline are important for the afflicted individuals and their caregivers [3].

After adjusting for beneficiary characteristics, we found that Black and Asian beneficiaries were less likely to use antidementia drugs, with a larger disparity at high levels of adherence relative to low levels of adherence. Hispanic beneficiaries were also less likely to use these drugs than Whites at higher levels of adherence. Given that poor adherence is a barrier to reaching any potential benefit of antidementia drugs [34], this implies that these patient sub-groups are benefitting less than other beneficiaries. The burden of dementia is disproportionately higher for racial/ethnic minorities, and the demonstrated disparities in the use of these drugs might increase overall disparities in the large and growing burden of this condition [30]. Earlier research on disparities in antidementia drug use showed that Hispanics with ADRD had higher odds of initiation than Whites and Blacks in the second half of 2009 [25]; our analyses, which focused on prevalent use, rather than initiation rates, showed lower adjusted odds of prevalent use at higher adherence levels for non-Whites from 2008–2016. Additionally, our results showing higher odds of antidementia drug use for people with less comorbidity are supportive of earlier evidence [38].

We also show that initiation of drug therapy often precedes diagnoses, sometimes by several years. There are several factors that may contribute to a physician’s decision to prescribe before giving a diagnosis. For example, physicians may be hesitant to diagnose one type of dementia because of uncertainty regarding the etiology. It is difficult to distinguish between AD, non-AD dementia, and mixed dementias without detailed longitudinal neuropsychological evaluation information, which is often not available to general practitioners who prescribe these drugs [2]. Despite hesitancy to give a specific diagnosis, physicians may offer pharmaceutical treatments for observed cognitive impairment, as evidenced in earlier research [22]. In addition to etiologic uncertainty, there may be societal factors that influence use of antidementia drugs without a diagnosis of AD. For example, societal stigma against dementia may cause beneficiaries and their families to resist such diagnoses, while still desiring treatment [39, 40]. Stigma may vary across different racial and ethnic groups and may in part explain the differential pre-diagnosis use of drugs that we observed [41]. One implication of our study is that Asians and Hispanics may have higher rates of underdiagnosis of ADRD than Black and White individuals, as evidenced by their higher rates of pre-diagnosis use of AChEIs and memantine.

Given the prevalence of AD medication use prior to the diagnosis of any related condition or symptom, it is clear that health care providers often observe evidence of cognitive decline well before this information is registered via claims as diagnoses. Claims data remain an important resource for ADRD research, but as has been shown in a related study, it is important for researchers to incorporate drug utilization data into their studies as a source of information on otherwise undocumented cognitive decline [42, 43].

Limitations

The Medicare claims data provide a comprehensive perspective on the use of donepezil, galantamine, rivastigmine, and memantine in the United States, and are a robust dataset for examining prescription drug utilization. A limitation, however, is that these data do not include individuals enrolled in Medicare Advantage or FFS without Part D. Additionally, claims for these drugs do not necessarily reflect use of the drugs; however, this study’s aim was to examine treatment patterns, which is a different construct than medication adherence. We use the term “adherence” for convention. Another limitation is measurement error in the timing and presence of dementia-related diagnoses; claims-based diagnoses have no information about disease severity, and can be inconsistent across providers. Indeed, some dementia is undiagnosed, which is why this study also included antidementia drug users who did not have any dementia-related diagnoses. While we acknowledge the likelihood of diagnostic measurement error, we note that recent evidence found diagnosis of dementia has improved over time and concordance with cognitive test-based measures of dementia is high [42, 43]. We also note that despite the potential for underdiagnosis and etiologic imprecision of ADRD diagnoses in claims, this study aims to describe the treatment patterns in the real-world context of diagnostic imprecision. Understanding these treatment patterns can aid in the development and implementation of interventions to improve treatment and dementia management. One other limitation is that these analyses omit combination donepezil/memantine (branded as Namzaric); this product was only approved by the FDA in late December 2014 [37], and had low levels of use during the two years that overlap with our sampling period (2015 and 2016).

Conclusions

Rates of pharmaceutical treatment are low and disparate in the Medicare population diagnosed with ADRD and dementia-related symptoms. Additionally, the timing of therapy initiation relative to diagnosis varies widely across race/ethnicity, suggesting differences in diagnostic and treatment practices across patient sub-groups. Pharmaceutical treatment with donepezil, galantamine, rivastigmine, and memantine has modest effectiveness, but for some people may delay the cognitive and functional decline associated with ADRD, and is recommended in treatment guidelines. Tailored prescribing for interested patients has potential value to individuals, families, and society, even if the delays to decline are brief. ADRD has a large burden that is expected to grow [1], and racial/ethnic differences in overall utilization and timing of utilization may exacerbate disparities in the burden. Future research should examine how these differences in use and timing of use affect outcomes of care in diverse populations.

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

Douglas Barthold is supported by NIH/NHLBI R01HL126804 and NIH R01HL130462, and was previously supported by NIA R01AG055401, NIA P30AG043073-01, NIA P01AG033559, University of Southern California Zumberge Research Fund (1R34AG049652), and the Schaeffer-Amgen Fellowship Program funded by Amgen.

Geoffrey Joyce and Patricia Ferido are supported by NIA R01AG055401.

Emmanuel Drabo is supported by USC-RCMAR Grant P30AG043073.

Zachary Marcum is supported by the National Institute on Aging of the National Institutes of Health under Award Number K76AG059929. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health.

Shelly Gray is supported by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention U01CE002967 and NIA U01AG006781.

Julie Zissimopoulos is supported by NIA R01AG055401 and P30AG043073.

Footnotes

Authors’ disclosures available online (https://www.j-alz.com/manuscript-disclosures/20-0133r1).

SUPPLEMENTARY MATERIAL

The supplementary material is available in the electronic version of this article: https://dx.doi.org/10.3233/JAD-200133.

REFERENCES

- [1].Zissimopoulos JM, Tysinger BC, St. Clair PA, Crimmins EM (2018) The impact of changes in population health and mortality on future prevalence of Alzheimer’s disease and other dementias in the United States. J Gerontol B Psychol Sci Soc Sci 73, S38–S47. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [2].Alzheimer’s Association (2019) 2019 Alzheimer’s disease facts and figures. Alzheimers Dement 15, 321–387. [Google Scholar]

- [3].Livingston G, Sommerlad A, Orgeta V, Costafreda SG, Huntley J, Ames D, Ballard C, Banerjee S, Burns A, Cohen-Mansfield J (2017) Dementia prevention, intervention, and care. Lancet 390, 2673–2734. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [4].Howard R, McShane R, Lindesay J, Ritchie C, Baldwin A, Barber R, Burns A, Dening T, Findlay D, Holmes C (2012) Donepezil and memantine for moderate-to-severe Alzheimer’s disease. N Engl J Med 366, 893–903. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [5].Howard R, McShane R, Lindesay J, Ritchie C, Baldwin A, Barber R, Burns A, Dening T, Findlay D, Holmes C (2015) Nursing home placement in the Donepezil and Memantine in Moderate to Severe Alzheimer’s Disease (DOMINO-AD) trial: secondary and post-hoc analyses. Lancet Neurol 14, 1171–1181. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [6].Birks JS (2006) Cholinesterase inhibitors for Alzheimer’s disease. Cochrane Database Syst Rev, CD005593. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [7].McShane R, Areosa Sastre A, Minakaran N (2006) Memantine for dementia. Cochrane Database Syst Rev, CD003154. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [8].Rountree SD, Atri A, Lopez OL, Doody RS (2013) Effectiveness of antidementia drugs in delaying Alzheimer’s disease progression. Alzheimers Dement 9, 338–345. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [9].O’Brien JT, Holmes C, Jones M, Jones R, Livingston G, McKeith I, Mittler P, Passmore P, Ritchie C, Robinson L (2017) Clinical practice with anti-dementia drugs: a revised (third) consensus statement from the British Association for Psychopharmacology. J Psychopharmacol 31, 147–168. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [10].Raina P, Santaguida P, Ismaila A, Patterson C, Cowan D, Levine M, Booker L, Oremus M (2008) Effectiveness of cholinesterase inhibitors and memantine for treating dementia: evidence review for a clinical practice guideline. Ann Intern Med 148, 379–397. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [11].Bond M, Rogers G, Peters J, Anderson R, Hoyle M, Miners A, Moxham T, Davis S, Thokala P, Wailoo A (2012) The effectiveness and cost-effectiveness of donepezil, galantamine, rivastigmine and memantine for the treatment of Alzheimer’s disease. Health Technol Assess 16, 1–470. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [12].Schmidt R, Hofer E, Bouwman F, Buerger K, Cordonnier C, Fladby T, Galimberti D, Georges J, Heneka M, Hort J (2015) EFNS-ENS/EAN Guideline on concomitant use of cholinesterase inhibitors and memantine in moderate to severe Alzheimer’s disease. Eur J Neurol 22, 889–898. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [13].Tan C-C, Yu J-T, Wang H-F, Tan M-S, Meng X-F, Wang C, Jiang T, Zhu X-C, Tan L (2014) Efficacy and safety of donepezil, galantamine, rivastigmine, and memantine for the treatment of Alzheimer’s disease: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Alzheimers Dis 41, 615–631. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [14].San-Juan-Rodriguez A, Zhang Y, He M, Hernandez I (2019) Association of antidementia therapies with time to skilled nursing facility admission and cardiovascular events among elderly adults with Alzheimer disease. JAMA Netw Open 2, e190213. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [15].Alzheimer’s Association Expert Advisory Workgroup on NAPA (2012) Workgroup on NAPA’s scientific agenda for a national initiative on Alzheimer’s disease. Alzheimers Dement 8, 357–371. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [16].Winslow BT, Onysko MK, Stob CM, Hazlewood KA (2011) Treatment of Alzheimer disease. Am Fam Physician 83, 1403. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [17].Bent-Ennakhil N, Coste F, Xie L, Aigbogun MS, Wang Y, Kariburyo F, Hartry A, Baser O, Neumann P, Fillit H (2017) A real-world analysis of treatment patterns for cholinesterase inhibitors and memantine among newly-diagnosed Alzheimer’s disease patients. Neurol Ther 6, 131–144. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [18].Theodorou AA, Johnson KM, Moore M, Ruf S, Wade T, Szychowski JA (2010) Drug utilization patterns in patients with Alzheimer’s disease. Am J Pharm Benefits 2, 77–82. [Google Scholar]

- [19].Campbell NL, Perkins AJ, Gao S, Skaar TC, Li L, Hendrie HC, Fowler N, Callahan CM, Boustani MA (2017) Adherence and tolerability of Alzheimer’s disease medications: a pragmatic randomized trial. J Am Geriatr Soc 65, 1497–1504. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [20].Hernandez S, McClendon MJ, Zhou X-HA, Sachs M, Lerner AJ (2010) Pharmacological treatment of Alzheimer’s disease: effect of race and demographic variables. J Alzheimers Dis 19, 665–672. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [21].Gilligan AM, Malone DC, Warholak TL, Armstrong EP (2012) Racial and ethnic disparities in Alzheimer’s disease pharmacotherapy exposure: an analysis across four state Medicaid populations. Am J Geriatr Pharmacother 10, 303–312. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [22].Tartaglia MC, Hu B, Mehta K, Neuhaus J, Yaffe K, Miller BL, Boxer A (2014) Demographic and neuropsychiatric factors associated with off-label medication use in frontotemporal dementia and Alzheimer’s disease. Alzheimer Dis Assoc Disord 28, 182. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [23].Zdanys K, Tampi RR (2008) A systematic review of off-label uses of memantine for psychiatric disorders. Prog Neuropsychopharmacol Biol Psychiatry 32, 1362–1374. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [24].Drabo EF, Barthold D, Joyce G, Ferido P, Chui HC, Zissimopoulos J (2019) Longitudinal analysis of dementia diagnosis and specialty care among racially diverse Medicare beneficiaries. Alzheimers Dement 15, 1402–1411. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [25].Thorpe CT, Fowler NR, Harrigan K, Zhao X, Kang Y, Hanlon JT, Gellad WF, Schleiden LJ, Thorpe JM (2016) Racial and ethnic differences in initiation and discontinuation of antidementia drugs by medicare beneficiaries. J Am Geriatr Soc 64, 1806–1814. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [26].McClendon MJ, Hernandez S, Smyth KA, Lerner AJ (2009) Memantine and acetylcholinesterase inhibitor treatment in cases of CDR 0.5 or questionable impairment. J Alzheimers Dis 16, 577–583. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [27].Koller D, Hua T, Bynum JP (2016) Treatment patterns with antidementia drugs in the United States: medicare cohort study. J Am Geriatr Soc 64, 1540–1548. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [28].Tang M-X, Cross P, Andrews H, Jacobs D, Small S, Bell K, Merchant C, Lantigua R, Costa R, Stern Y (2001) Incidence of AD in African-Americans, Caribbean hispanics, and caucasians in northern Manhattan. Neurology 56, 49–56. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [29].Navaie-Waliser M, Feldman PH, Gould DA, Levine C, Kuerbis AN, Donelan K (2001) The experiences and challenges of informal caregivers common themes and differences among Whites, Blacks, and Hispanics. Gerontologist 41, 733–741. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [30].Babulal GM, Quiroz YT, Albensi BC, Arenaza-Urquijo E, Astell AJ, Babiloni C, Bahar-Fuchs A, Bell J, Bowman GL, Brickman AM (2019) Perspectives on ethnic and racial disparities in Alzheimer’s disease and related dementias: Update and areas of immediate need. Alzheimers Dement 15, 292–312. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [31].Sinyavskaya L, Gauthier S, Renoux C, Dell’Aniello S, Suissa S, Brassard P (2018) Comparative effect of statins on the risk of incident Alzheimer disease. Neurology 90, e179–e187. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [32].Imfeld P, Brauchli Pernus YB, Jick SS, Meier CR (2013) Epidemiology, co-morbidities, and medication use of patients with Alzheimer’s disease or vascular dementia in the UK. J Alzheimers Dis 35, 565–573. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [33].Cerejeira J, Lagarto L, Mukaetova-Ladinska E (2012) Behavioral and psychological symptoms of dementia. Front Neurol 3, 73. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [34].Brady R, Weinman J (2013) Adherence to cholinesterase inhibitors in Alzheimer’s disease: a review. Dement Geriatr Cogn Disord 35, 351–363. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [35].Bonito A, Bann C, Eicheldinger C, Carpenter L (2008) Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality, and Center for Medicare and Medicaid Services, Rockville, MD. [Google Scholar]

- [36].Li P, Kim MM, Doshi JA (2010) Comparison of the performance of the CMS Hierarchical Condition Category (CMS-HCC) risk adjuster with the Charlson and Elixhauser comorbidity measures in predicting mortality. BMC Health Serv Res 10, 1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [37].United States Food and Drug Administration (2019) Orange Book: Approved Drug Products with Therapeutic Equivalence Evaluations. US Department of Health and Human Services. [Google Scholar]

- [38].Bohlken J, Jacob L, van den Bussche H, Kostev K (2018) The influence of polypharmacy on the initiation of anti-dementia therapy in Germany. J Alzheimers Dis 64, 827–833. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [39].Pentzek M, Wollny A, Wiese B, Jessen F, Haller F, Maier W, Riedel-Heller SG, Angermeyer MC, Bickel H, Mösch E (2009) Apart from nihilism and stigma: what influences general practitioners’ accuracy in identifying incident dementia? Am J Geriatr Psychiatry 17, 965–975. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [40].Herrmann LK, Welter E, Leverenz J, Lerner AJ, Udelson N, Kanetsky C, Sajatovic M (2018) A systematic review of dementia-related stigma research: can we move the stigma dial? The Am J Geriatr Psychiatry 26, 316–331. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [41].Abdullah T, Brown TL (2011) Mental illness stigma and ethnocultural beliefs, values, and norms: An integrative review. Clin Psychol Rev 31, 934–948. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [42].Chen Y, Tysinger B, Crimmins E, Zissimopoulos JM (2019) Analysis of dementia in the US population using Medicare claims: Insights from linked survey and administrative claims data. Alzheimers Dement (NY) 5, 197–207. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [43].Thunell J, Ferido P, Zissimopoulos J (2019) Measuring Alzheimer’s disease and other dementias in diverse populations using medicare claims data. J Alzheimers Dis 72, 29–33. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.