Abstract

Purpose:

Veliparib is an oral inhibitor of poly(ADP-ribose) polymerase (PARP)-1 and −2. PARP-1 expression may be increased in cancer, and this increase confers resistance to cytotoxic agents. We aimed to determine the recommended phase 2 dose (RP2D), maximum tolerated dose (MTD), dose-limiting toxicity (DLT), and pharmacokinetics (PK) of veliparib combined with paclitaxel and carboplatin.

Methods:

Eligibility criteria included patients with advanced solid tumors treated with ≤3 prior regimens. Paclitaxel and carboplatin were administered on day 3 of a 21-day cycle. Veliparib was given PO BID days 1-7, except for cycle 1 in the first 46 patients to serve as control for toxicity and PK. A standard “3+3” design started veliparib at 10 mg BID, paclitaxel at 150 mg/m2, and carboplatin AUC 6. The pharmacokinetic metabolism (PKs) of veliparib, paclitaxel, and carboplatin were determined by LC-MS/MS and AAS during cycles 1 and 2.

Results:

Seventy-three patients were enrolled. Toxicities were as expected with carboplatin/paclitaxel chemotherapy, including neutropenia, thrombocytopenia, and peripheral neuropathy. DLTs were seen in 2 of 7 evaluable patients at the maximum administered dose (MAD): veliparib 120 mg BID, paclitaxel 200 mg/m2, and carboplatin AUC 6 (febrile neutropenia, hyponatremia). The MTD and RP2D was determined to be veliparib 100 mg BID, paclitaxel 200 mg/m2, and carboplatin AUC 6. Median number of cycles of the 3-agent combination was 4 (1-16). We observed 22 partial and 5 complete responses. Veliparib did not affect paclitaxel or carboplatin PK disposition.

Conclusion:

Veliparib, paclitaxel, and carboplatin were well-tolerated and demonstrated promising anti-tumor activity.

Keywords: Veliparib, poly(ADP-ribose) polymerase, paclitaxel, carboplatin, phase 1, clinical trial, advanced cancer

INTRODUCTION

PARP-1 and −2 are nuclear enzymes that catalyze the synthesis of poly-ADP ribose (PAR) at sites of single-stranded DNA breaks (SSB). The branched-chain, negatively charged PAR polymers are attached to histones and other proteins at the site of SSB leading to the recruitment of machinery for base-excision DNA repair (BER)[1]. Cell lines lacking the function of BRCA1 or BRCA2 gene products are exceptionally sensitive to inhibition of PARP activity [2,3], suggesting a synthetic lethal relationship between BRCA1,2 and PARP1,2. This observation is consistent with the role of BRCA1 and BRCA2 in homologous recombination DNA repair [4,5]. PARP expression has been observed to be higher in various solid tumors when compared to normal tissue [6-12], and this over-expression has been linked to chemoresistance. PARP inhibitors have conversely been shown to potentiate cell death in response to DNA damage by chemotherapy or radiotherapy [13,14]. Several PARP inhibitors have undergone clinical development [15]. Veliparib (ABT-888) is an orally bioavailable inhibitor of PARP-1 and PARP-2. Preliminary results of a study of veliparib as a single agent in patients with BRCA 1/2-mutated cancer (BRCA+), platinum-refractory ovarian cancer, or basal-like breast cancer showed tumor responses and prolonged stable disease [16]. Single-agent activity has also been reported in patients with ovarian, breast, and prostate cancers, most notably in patients with germline or somatic mutations in BRCA and other genes that are directly involved in DNA repair. There are currently three PARP inhibitors approved by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) for advanced ovarian cancer in women with germline BRCA1 or BRCA2 mutations or in combination with chemotherapy: niraparib, olaparib, rucaparib [17-19]. Olaparib and talazoparib are also approved for patients with advanced, germline-BRCA-mutated, HER2-negative breast cancer.

While the PARP inhibitors, as a class, have shown single-agent activity in the limited tumor types above, there remains an unmet need for durable cancer control and activity in a broader range of tumors. Synergy has been observed between DNA damaging cytotoxic agents and PARP inhibitor compounds, including platinum agents [20-22]. A study of veliparib in combination with temozolomide in patients with advanced melanoma showed a trend toward improved progression-free survival (PFS) with either 20 mg or 40 mg of veliparib daily vs. placebo [23] and a randomized study of temozolomide plus veliparib vs. placebo in patients with refractory small cell lung cancer showed a significant improvement in overall response rate, although the primary endpoint of PFS improvement was not reached [24]. A study of veliparib in combination with oral daily cyclophosphamide observed seven partial responses out of 35 patients enrolled [25].

The combination of paclitaxel and carboplatin is an effective and well-tolerated chemotherapy doublet that has well-established clinical activity in cancers of the lung, ovary, urothelium, cervix, endometrium, head and neck as well as Kaposi’s sarcoma. Moreover, paclitaxel has been shown to abrogate the thrombocytopenia seen with carboplatin [26]. We hypothesized that veliparib would enhance the effect of carboplatin-associated DNA damage in cancer cells, and that the combination might demonstrate enhanced antitumor activity. The present study was designed to investigate the safety profile and determine the maximum tolerated dose of veliparib in combination with paclitaxel and carboplatin.

PATIENTS AND METHODS

Inclusion Criteria

Eligible patients had a histologically confirmed non-hematologic malignancy for which 3 or fewer systemic treatment regimens had been administered previously for advanced disease. Patients were ≥18 years of age, had an ECOG performance status less of 0-2, and a life-expectancy of greater than 12 weeks. Adequate organ and marrow function was required: absolute neutrophil count ≥ 1500/mcL, platelet count ≥ 100,000/mcL, total bilirubin ≤ 1.5 x institutional upper limit of normal (ULN), AST(SGOT) and ALT(SGPT) ≤2.5 x institutional ULN, creatinine ≤ ULN or estimated creatinine clearance ≥ 60 mL/min/1.73 m2 for patients with creatinine levels above the institutional ULN. Patients with peripheral neuropathy greater than CTCAE grade 1 were excluded, as were patients who were pregnant or who had a history of HIV infection, bleeding diathesis, or seizure disorder. Patients with brain metastases were required to have stable disease for at least 4 weeks following local therapy. Assessment of BRCA status was not mandated, and patients with a known BRCA1 or BRCA2 germline mutation were enrolled in a separate cohort that will be reported separately.

Study Design

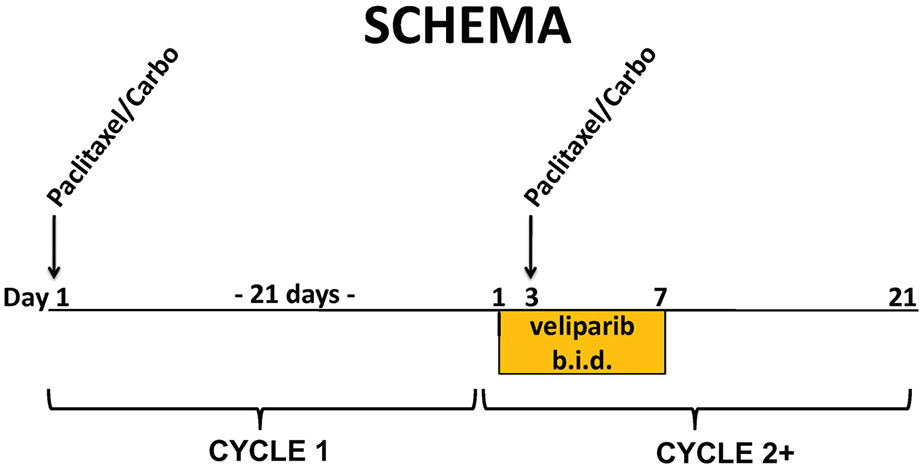

This was a multi-center, open-label phase 1 study. Subjects were enrolled at five study sites under an IRB-approved protocol (NCT00535119). Informed consent was obtained from all individual participants included in the study. The study was conducted in compliance with the Declaration of Helsinki. Veliparib was supplied by Cancer Therapy Evaluation Program of the National Cancer Institute as 10 mg and 50 mg tablets and was administered every 12 hours without regard to meals on days 1-7 of each 21-day cycle. For the first 46 patients, veliparib was not administered until cycle 2 so that the effect of veliparib on paclitaxel and carboplatin pharmacokinetics (PK) as well as its contribution to toxicity could be compared directly to chemotherapy alone. DLTs were assessed during cycle 2. Paclitaxel and carboplatin were obtained commercially and administered intravenously on day 1 of cycle 1 and on day 3 of cycle 2 onward (Figure 1). Patients who had toxicity during cycle 1 (carboplatin and paclitaxel alone), and thus required administration of G-CSF or dose reduction of chemotherapy for cycle 2, were not evaluable for DLT but were permitted to remain on study. These patients are included in the overall toxicity summary and in the assessment of tumor response. This schedule was designed so that there would be veliparib exposure at the time of chemotherapy administration.

Figure 1. Study schema:

carboplatin and paclitaxel alone were administered on day 1 of the first 21-day cycle. Veliparib was administered PO twice daily on days 1–7, and chemotherapy administered IV on day 3 of the second and subsequent cycles. Study agents were administered over a 21-day cycle. Paclitaxel and carboplatin were administered intravenously (day 1 of lead-in cycle 1 and day 3 of subsequent cycles with veliparib. Oral veliparib was administered twice daily on days 1–7 of each cycle, except for lead in cycle 1 for the first 46 patients

A modified Fibonacci dose escalation scheme was used in the study design. The starting dose level was carboplatin AUC 6, paclitaxel 150 mg/m2, and veliparib 10 mg bid. The protocol recommended that up to 6 cycles of study treatment be administered, although additional cycles of treatment could be given if there was clinical benefit at the discretion of the investigator. After the first 46 patients were enrolled into dose levels 1 to 8, the study was amended so that veliparib as well as carboplatin and paclitaxel were administered together in cycle 1.The remaining subjects were enrolled on dose levels 7, 8, and 7A in dose escalation and expansion.

Definition of DLT and MTD

For the first 46 patients enrolled on this study, dose-limiting toxicity (DLT) was assessed during cycle 2, which was the first cycle in which veliparib was combined with chemotherapy. Patients who experienced toxicity in cycle 1 that required dose reduction or use of growth factors in cycle 2 were allowed to continue study treatment at the discretion of the investigator, but were not evaluable for DLT assessment of the veliparib/paclitaxel/carboplatin regimen. Beyond patient 46, all 3 agents were administered in cycle 1, during which DLT was assessed. DLT was defined as: ≥ grade 3 non-hematologic toxicity (including nausea or vomiting that lasted longer than 48 hours despite maximal medical therapy); absolute neutrophil count < 1000 lasting longer than 7 days; grade 4 thrombocytopenia; grade 3 or grade 4 neutropenia associated with sepsis or fever > 38°C; delay in starting cycle 3 by more than 2 weeks due to toxicity; abnormal non-hematological laboratory criteria ≥ grade 3) if clinically significant and drug related. Colony stimulating factors (G-CSF, GM-CSF) were not allowed routinely in cycles 1 or 2, but were permitted in later treatment cycles at the discretion of the treating investigator. The MTD was defined as the highest dose at which ≤1 out of 6 patients experienced a DLT.

Patient Evaluation

After patients signed informed consent, screening studies were obtained to determine eligibility including detailed medical history, physical exam, performance status, disease assessment by cross-sectional imaging (CT or MRI) complete blood count (CBC) and serum chemistry panel including liver function tests. CBC and serum chemistry panel were obtained weekly during cycles 1 and 2 and at the start of every cycle thereafter. Interim medical history, physical exam, and performance status were also assessed at the start of every cycle, and tumor response was assessed every 2 cycles (post cycle 3 and every 2 cycles thereafter for the first 46 subjects). Tumor response and progression were assessed by RECIST 1.0 [27].

Dose Modifications

Grade 4 neutropenia, grade 3 neutropenia with fever, or grade ≥ 2 peripheral neuropathy or arthralgia/myalgia led to a reduction in paclitaxel dose by 25 mg/m2. Up to two dose reductions were allowed. Grade 3 or grade 4 thrombocytopenia led to a reduction in carboplatin dose by one AUC level. Up to two dose reductions for thrombocytopenia were allowed. Paclitaxel and veliparib were held for ≥ grade 2 SGOT elevation or ≥ grade 3 elevation in total bilirubin.

Pharmacokinetic Methods

Peripheral blood samples were collected in heparinized tubes prior to and at 0.5, 1, 1.5, 2, 3, 4, 6, and 8 h after veliparib dosing on Day 1 (for veliparib PK), and prior to and at 0.5, 1, 1.5, 2, 3, 3.25, 4, 6, 8, and 24 h after veliparib dosing (coinciding with start paclitaxel infusion) on Day 3 (for veliparib, carboplatin and paclitaxel PK). Forty-six patients received a single cycle of paclitaxel and carboplatin without veliparib before the start of triplet therapy, and they were also studied prior to and at 0.5, 1, 1.5, 2, 3, 3.25, 4, 6, 8, and 24 h after start of paclitaxel infusion on Day 3 (for carboplatin and paclitaxel PK). Each blood sample was centrifuged at approximately 1,000 x g for 10 minutes, and plasma was stored at −70°C or colder until analysis. Plasma concentrations of veliparib were quantitated with an LC-MS assay validated to FDA guidance [28]. Concentrations of ultrafilterable platinum were quantitated by atomic absorption spectrophotometry (AAS) as previously described [29]. Plasma concentrations of paclitaxel were quantitated with an LC-MS/MS assay as described previously [30], utilizing [13C6]-paclitaxel (AlsaChim, Illkirch Graffenstaden, France) as internal standard. Plasma PK parameters were derived from the data by non-compartmental methods with PK Solutions 2.0™ (Summit Research Services, Montrose, CO, USA). Mean prediction error and root mean squared prediction error for targeting carboplatin AUC was calculated as described [31]. The time above a plasma paclitaxel concentration of 0.05 μM (Tc>0.05 μM) was calculated from absolute dose and the 24 h concentration value using the MyCare Drug Exposure Calculator [32] Significance was evaluated with IBM SPSS Statistics version 24 (International Business Machines Corp., Armonk, NY, USA).

Statistical Methods

The primary objective of this study was to determine the MTD and recommended dose for phase 2 studies (RP2D) of veliparib in combination with carboplatin and paclitaxel in patients with advanced solid malignancies. The secondary objectives were as follows: (1) determine dose-limiting and other toxicities of the veliparib/carboplatin/paclitaxel combination; (2) observe preliminary anti-tumor activity; and (3) evaluate the PK parameters of the combination regimen.

This phase 1 trial followed a standard 3+3 dose-escalation schema. Descriptive statistics were used for the analysis of baseline demographic and clinical characteristics, responses, and maximum grade adverse events of all cycles, carboplatin and paclitaxel only cycle, and first veliparib cycle. Intrapatient comparisons of cycle 1 (carboplatin and paclitaxel only cycle) and cycle 2 (first ABT cycle) values of neutrophil counts and relative change in neutrophil counts were performed for 27 patients who were evaluable for DLT using a two-sided Wilcox signed rank test.

RESULTS

Demographics and enrollment

A total of 73 patients were enrolled between 2007 and 2012 at 5 institutions (Table 1). The median age was 60 years (range 33-86). The different tumor types are listed in Table 1, with the most common tumor types being lung (23%) and breast cancer (21%). Patients who had been treated with up to 3 prior chemotherapy regimens were eligible for this study. A total of 40 patients had received prior chemotherapy (22=1 regimen, 12=2 regimens, 6=3 regimens), and 33 patients were treatment-naißve.

Table 1.

Patient Demographics.

| Characteristic | No. of patients (%) |

|---|---|

| N | 73 |

| Age, Years | |

| Median | 60 |

| Range | 33-86 |

| Gender | |

| Male | 40 (54.8) |

| Female | 33 (45.2) |

| ECOG Performance Status | |

| 0 | 37 (50.7) |

| 1 | 31 (42.5) |

| 2 | 5 (6.9) |

| Primary Cancer | |

| Non-small cell lung | 16 (22) |

| Breast | 16 (21.9) |

| Melanoma | 10 (13.7) |

| Head & neck | 9 (12.3) |

| Bladder | 6 (8.2) |

| Cholangiocarcinoma | 2 (2.7) |

| Esophageal | 2 (2.7) |

| Adenoid cystic of lung | 1 (1.4) |

| Adrenocortical carcinoma | 1 (1.4) |

| Ampulla of Vater | 1 (1.4) |

| Cervix | 1 (1.4) |

| Myxoid chondrosarcoma | 1 (1.4) |

| Prostate | 1 (1.4) |

| Small cell lung | 1 (1.4) |

| Stomach | 1 (1.4) |

| Uterine | 1 (1.4) |

| Olfactory esthesioneuroblastoma | 1 (1.9) |

| Carcinoma of unknown origin | 3 (4.1) |

| No. of prior therapy regimens (cytotoxic only) | |

| 0 | 33 (45.2) |

| 1 | 22 (30.1) |

| 2 | 12 (16.4) |

| 3 | 6 (8.2) |

| No. of cycles* | |

| Median | 4 |

| Range | 1-16 |

Abbreviation: ECOG PS: Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group performance status.

only cycles where veliparib was given were counted.

The first 46 patients enrolled on this study were treated with carboplatin and paclitaxel alone in cycle 1. This lead-in cycle was designed as a control to assess the effect of veliparib on toxicity and PK in cycle 2. As such, DLT was assessed during cycle 2 for this group of patients. Seventeen of these first 46 patients were inevaluable for DLT (21 of the 73 total enrolled), most because toxicity during cycle 1 (carboplatin and paclitaxel alone) necessitated a dose reduction, delay or use of growth factor support during cycle 2. These patients, however, were allowed to proceed with subsequent cycles of study treatment and were included in the response analysis. Six patients were unable to be treated beyond cycle 1 with carboplatin/paclitaxel and so were excluded from the analysis. The protocol was subsequently amended after the first 46 patients, eliminating the lead-in cycle with carboplatin and paclitaxel alone. This change resulted from the unexpected number of patients who were inevaluable because of toxicity during cycle 1 with chemotherapy alone (primarily asymptomatic neutropenia) and preliminary data suggesting that, through dose level 7, veliparib did not have an adverse effect on toxicity or on the PK of carboplatin and paclitaxel. Patients received a median of 4 cycles of therapy with the triple combination of carboplatin, paclitaxel, and veliparib (range: 1-16). Eleven subjects received more than 6 cycles of study treatment.

Toxicity

Dose-limiting toxicities occurred in 8 patients during their DLT observation cycle (cycle 2 for the first 46 subjects and cycle 1 for subsequent subjects) (Table 2). The most frequent toxicity observed during the DLT assessment period was neutropenia (57%) (Table 3), highest grade 3 in 19% and grade 4 in 31%). During the initial cycle of carboplatin and paclitaxel, neutropenia was seen in 56% of patients (20% grade 3 and 24% grade 4). Febrile neutropenia or grade 3-4 neutropenia lasting more than 7 days was observed less frequently (7 patients total across the dose levels). The toxicities observed in cycle 2 were consistent with those observed with carboplatin and paclitaxel alone, namely myelosuppression and cumulative peripheral neuropathy. Additional toxicities are listed in Table 3, Supplemental Table 1, and Supplemental Table 2.

Table 2.

Dose Levels and Dose-limiting Toxicities (DLTs).

| Dose Level | Veliparib Dose (mg BID) |

Carboplatin Dose (AUC) |

Paclitaxel Dose (mg/m2) |

# Enrolled | # Evaluable for DLT |

DLTs |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Level 1 | 10 | 6 | 150 | 5 | 3 | 0 |

| Level 2 | 20 | 6 | 150 | 8 | 7 | Grade 3 neutropenia > 7 days |

| Level 3 | 20 | 6 | 175 | 3 | 3 | 0 |

| Level 4 | 40 | 6 | 175 | 3 | 3 | 0 |

| Level 5 | 40 | 6 | 200 | 13 | 6 | Grade 3 febrile neutropenia |

| Level 6 | 50 | 6 | 200 | 5 | 3 | 0 |

| Level 7 | 80 | 6 | 200 | 11 | 6 | Grade 3 febrile neutropenia |

| Level 7B | 100 | 6 | 200 | 15 | 14 | Grade 4 sepsis and neutropenia Grade 4 neutropenia Grade 4 febrile neutropenia and Grade 3 fatigue |

| Level 8 | 120 | 6 | 200 | 10 | 7 | Grade 4 hyponatremia, Grade 3 nausea Grade 3 febrile neutropenia |

Table 3.

Toxicity by Grade, First Cycle including Veliparib (n=73).

| Event | Any Grade | Grade 1 | Grade 2 | Grade 3 | Grade 4 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| number of patients (%) | |||||

| Any adverse event | 67 (92) | 57 (78) | 46 (63) | 34 (47) | 26 (36) |

| Neutrophil count decreased | 42 (57) | 1 (1) | 4 (5) | 14 (19) | 23 (31) |

| White blood cell decreased | 40 (55) | 6 (8) | 14 (19) | 17 (23) | 3 (4) |

| Nausea | 28 (38) | 22 (30) | 5 (7) | 1 (1) | 0 |

| Fatigue | 27 (37) | 18 (24) | 5 (7) | 4 (5) | 0 |

| Anemia | 24 (33) | 4 (5) | 18 (25) | 2 (3) | 0 |

| Alopecia | 17 (23) | 13 (18) | 4 (5) | 0 | 0 |

| Lymphocyte count decreased | 14 (19) | 2 (3) | 8 (11) | 3 (4) | 1 (1) |

| Platelet count decreased | 13 (18) | 7 (10) | 2 (3) | 4 (5) | 0 |

| Vomiting | 9 (12) | 7 (10) | 2 (3) | 0 | 0 |

| Myalgia | 8 (11) | 6 (8) | 2 (3) | 0 | 0 |

| Peripheral sensory neuropathy | 7 (10) | 7 (10) | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Constipation | 6 (8) | 4 (5) | 2 (3) | 0 | 0 |

| Arthralgia | 6 (8) | 5 (7) | 1 (1) | 0 | 0 |

| Hyponatremia | 5 (7) | 3 (4) | 0 | 1 (1) | 1 (1) |

| Diarrhea | 5 (7) | 5 (7) | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Anorexia | 4 (5) | 4 (5) | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Allergic reaction | 3 (4) | 2 (3) | 0 | 0 | 1 (1) |

| Fever | 3 (4) | 2 (3) | 0 | 1 (1) | 0 |

| Hypoalbuminemia | 3 (4) | 1 (1) | 2 (3) | 0 | 0 |

| Dyspepsia | 3 (4) | 2 (3) | 1 (1) | 0 | 0 |

| Dyspnea | 3 (4) | 2 (3) | 1 (1) | 0 | 0 |

| Creatinine increased | 3 (4) | 3 (4) | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Pruritus | 3 (4) | 3 (4) | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Dizziness | 3 (4) | 3 (4) | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Edema limbs | 3 (4) | 3 (4) | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Headache | 3 (4) | 3 (4) | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Febrile neutropenia | 5 (7) | 0 | 0 | 3(4) | 2 (3) |

| Sepsis | 2 (3) | 0 | 0 | 0 | 2 (3) |

| Hypocalcemia | 2 (3) | 0 | 1 (1) | 1 (1) | 0 |

| Alkaline phosphatase increased | 2 (3) | 1 (1) | 1 (1) | 0 | 0 |

| Weight loss | 2 (3) | 2 (3) | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Flushing | 2 (3) | 2 (3) | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Cough | 2 (3) | 2 (3) | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Rash maculopapular | 2 (3) | 2 (3) | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Mucositis oropharyngeal | 3 (4) | 3 (4) | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Dysgeusia | 2 (3) | 2 (3) | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Dry mouth | 2 (3) | 2 (3) | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Dysphagia | 2 (3) | 2 (3) | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Alanine aminotransferase increased | 2 (3) | 2 (3) | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Aspartate aminotransferase increased | 2 (3) | 2 (3) | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Presyncope | 1 (1) | 0 | 0 | 1 (1) | 0 |

| Hypophosphatemia | 1 (1) | 0 | 0 | 1 (1) | 0 |

| Dehydration | 1 (1) | 0 | 1 (1) | 0 | 0 |

| Cytokine release syndrome | 1 (1) | 0 | 1 (1) | 0 | 0 |

| Muscle weakness | 2(2) | 1(1) | 1 (1) | 0 | 0 |

| Erythema multiforme | 1 (1) | 0 | 1 (1) | 0 | 0 |

| Upper respiratory infection | 1 (1) | 0 | 1 (1) | 0 | 0 |

| Hypomagnesemia | 1 (1) | 0 | 1 (1) | 0 | 0 |

| Hiccups | 1 (1) | 1 (1) | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Blood bilirubin increased | 1 (1) | 1 (1) | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Anxiety | 1 (1) | 1 (1) | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Non-cardiac chest pain | 1 (1) | 1 (1) | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Flu like symptoms | 1 (1) | 1 (1) | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Tremor | 1 (1) | 1 (1) | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Insomnia | 1 (1) | 1 (1) | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Esophagitis | 1 (1) | 1 (1) | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Sinus disorder | 1 (1) | 1 (1) | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Bone pain | 1 (1) | 1 (1) | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Chills | 1 (1) | 1 (1) | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Purpura | 1 (1) | 1 (1) | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Dysesthesia | 1 (1) | 1 (1) | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Paresthesia | 1 (1) | 1 (1) | 0 | 0 | 0 |

There were two DLTs out of six evaluable patients treated at dose level 8 (febrile neutropenia and Grade 4 hyponatremia plus grade 3 nausea), which was thus declared intolerable and the maximum administered dose (MAD). Dose level 8 included veliparib at a dose of 120 mg bid. The study was modified at this point to add a dose level (7B) with a veliparib dose of 100 mg bid, in between this dose and the 80 mg bid dose used in dose level 7 (in which there was 1/6 DLTs). There was one DLT (febrile neutropenia) seen in the first 6 patients treated at dose level 7B. An additional 8 patients were treated as part of an expansion cohort at this dose level. In this group, one additional DLT of febrile neutropenia was observed and a second subject had neutropenia (nadir 283) without fever that lasted 8 days. Dose level 7B was declared the MTD and RP2D.

Pharmacokinetics

Veliparib PK parameters are presented in Supplemental Table 3. Exposure appeared to increase linearly with dose with an overall half-life of 5.1 h and an apparent clearance of 27.5 L/h. Veliparib Cmax appeared similar in the absence and presence of carboplatin and paclitaxel, while a comparison of AUC (day 1 veliparib alone AUC0-inf vs day 3 veliparib in combination AUC0-12) resulted in barely significantly lower than expected AUC on day 3 in the presence of carboplatin and paclitaxel(P=0.049 by exact Wilcoxon).

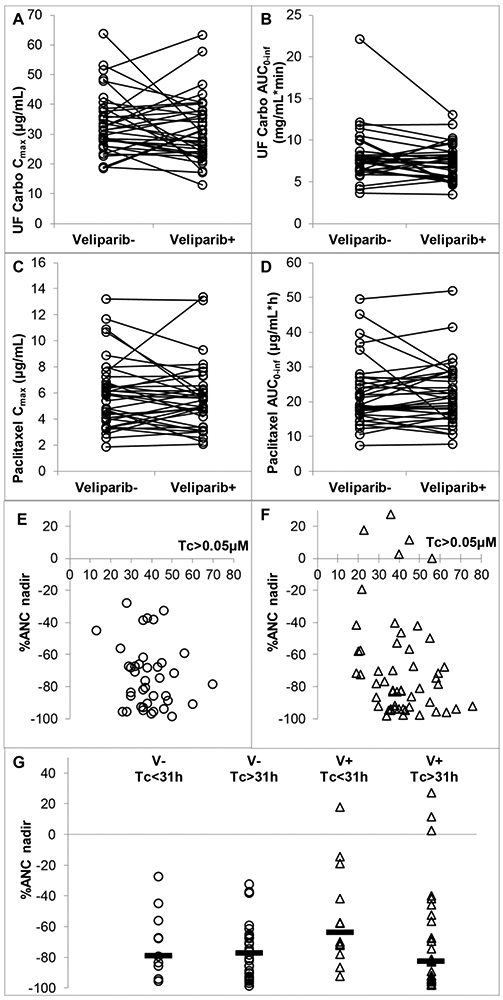

Ultrafilterable carboplatin pharmacokinetic parameters are shown in Figure 2A,B and Supplemental Table 4. Carboplatin exposure was not impacted by the presence of veliparib or by veliparib dose. P-values by 2-sided exact Wilcoxon signed rank tests were: Cmax 0.352, AUC0-inf 069, CL 0.136. The ability to target an ultrafilterable carboplatin AUC of 6 mg•min/mL in the absence and presence of veliparib was characterized by the mean prediction error (ME) as a measure of bias and the root mean squared prediction error (RMSE) as a measure of precision. In the absence of veliparib, ME was 1.88 mg•min/mL (or 31% of AUC 6 mg•min/mL) and RMSE was 3.45 mg•min/mL (or 57% of AUC 6 mg•min/mL). In the presence of veliparib, ME was 1.32 mg•min/mL (or 22% of AUC 6 mg•min/mL) and RMSE was 2.70 mg•min/mL (or 45% of AUC 6 mg•min/mL).

Figure 2. Pharmacokinetics:

PK parameters of ultrafilterable carboplatin (a, b) and paclitaxel (c, d) in the absence and presence of veliparib. ANC nadir (percentage of baseline) as a function of time above plasma paclitaxel concentration of 0.05 μM (Tc > 0.05μM) in the absence (e) and presence (f) of veliparib, and (g) the ANC nadir in the absence and presence of veliparib, split at the (Tc > 0.05 μM) = 31 h point (median indicted by horizontal bar). Pharmacokinetics and Pharmacodynamics: 1A: carboplatin Cmax is shown following administration during cycle 1 (veliparib −) and cycle 2 (veliparib +). 1B: carboplatin AUC is shown following administration during cycle 1 (veliparib −) and cycle 2 (veliparib +). 1C: paclitaxel Cmax is shown following administration during cycle 1 (veliparib −) and cycle 2 (veliparib +). 1D: paclitaxel AUC is shown following administration during cycle 1 (veliparib −) and cycle 2 (veliparib +). 1E, F: scatter plot of change in absolute neutrophil count (ANC) nadir (as a percentage of baseline) plotted as a function of time (hours) above plasma paclitaxel concentration of 0.05 μM (Tc > 0.05 μM). 1E—without veliparib. 1F—with veliparib. 1G—scatter plot of nadir ANC as percentage change from baseline. Data split at the value of (Tc > 0.05 μM) = 31 h, which has been reported as a cutoff for dose reduction [33], and by presence or absence of veliparib

Paclitaxel PK parameters are presented in Fig 2C,D and Supplemental Table 5. As with carboplatin, paclitaxel exposure was not impacted by the presence of veliparib or by veliparib dose. P-values by 2-sided exact Wilcoxon signed rank tests were: Cmax 0.514, AUC0-inf 0.468.

Pharmacodynamics

The nadir (ANC) nadir (as a percentage change from baseline) was plotted as a function of time (hours) elapsed above plasma paclitaxel concentration of 0.05 μM (Tc>0.05μM) (Fig. 2E,F: in the absence and presence of veliparib, respectively). Within patients, there was no significant difference in the (Tc>0.05 μM) value in the absence and presence of veliparib (P=0.828 by 2-sided exact Wilcoxon signed rank test). To evaluate whether veliparib impacted the relationship between (Tc>0.05 μM) and ANC nadir, the data was split at the value of (Tc>0.05 μM)=31 hours, see Figure. 2G, which has been reported as a cutoff for dose reduction [33]. In the absence of veliparib, there appeared to be no difference in median ANC nadir (Tc>0.05 μM)<31 vs (Tc>0.05 μM)>31, while in the presence of veliparib, such a difference did appear to be present (P=0.032 by Mann Whitney, not corrected for multiple testing).

Clinical Efficacy

With respect to clinical efficacy, complete responses (CRs) were observed in 5 patients. These CRs were observed in 3 patients with breast cancer, one with biopsy-confirmed metstatic urothelial carcinoma that was durable for over one year, and one with NSCLC. Twenty-two partial responses (PRs) were observed in patients with breast, lung, head and neck squamous, urothelial, uterine, prostate, stomach, melanoma, and carcinoma of unknown origin (Table 4). Of the patients who experienced a PR, 12 had received prior chemotherapy. Of note, there was not a clear association between dose level and response. Similarly, we did not observe a difference in response between the patients who received veliparib starting at cycle 1 or at cycle 2.

Table 4.

Responses (By Tumor Type and Dose Level).

| # Evaluable | CR | PR | SD | PD | ORR* (%) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| All Patients | 67 | 5 | 22 | 32 | 8 | 27/67 (40%) |

| By Tumor Type | ||||||

| Lung | 16 | 1 | 6 | 7 | 2 | 7/16 (44%) |

| Breast | 13 | 3 | 6 | 2 | 2 | 9/13 (69%) |

| Melanoma | 9 | 0 | 1 | 7 | 1 | 1/9 (11%) |

| Head & Neck | 8 | 0 | 3 | 5 | 0 | 3/8 (38%) |

| Bladder | 6 | 1 | 2 | 2 | 1 | 3/6 (50%) |

| Carcinoma of unknown origin | 3 | 0 | 1 | 2 | 0 | 1/3 (33%) |

| Esophageal | 2 | 0 | 0 | 2 | 0 | 0/2 (0%) |

| Cholangiocarcinoma | 2 | 0 | 0 | 2 | 0 | 0/2 (0%) |

| Ampulla of Vater | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0/1 (0%) |

| Adrenalcortical carcinoma | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0/1 (0%) |

| Stomach | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1/1 (100%) |

| Uterine | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1/1 (100%) |

| Prostate | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1/1 (100%) |

| Myxoid chondrosarcoma | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0/1 (0%) |

| Adenoid cystic of lung | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0/1 (0%) |

| Cervix | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0/1 (0%) |

| By Dose Level | ||||||

| Level 1 | 5 | 0 | 2 | 2 | 1 | 2/5 (40%) |

| Level 2 | 8 | 1 | 1 | 6 | 0 | 2/8(25%) |

| Level 3 | 3 | 0 | 1 | 2 | 0 | 1/3 (33%) |

| Level 4 | 3 | 0 | 1 | 2 | 0 | 1/3 (33%) |

| Level 5 | 12 | 2 | 4 | 5 | 1 | 6/12 (50%) |

| Level 6 | 5 | 1 | 1 | 2 | 1 | 2/5 (40%) |

| Level 7 | 9 | 1 | 5 | 2 | 1 | 6/9 (67%) |

| Level 7B | 14 | 0 | 3 | 8 | 3 | 3/14 (21%) |

| Level 8 | 8 | 0 | 4 | 3 | 1 | 4/8 (50%) |

Abbreviation: ORR-Overall response rate

DISCUSSION

This study was designed to determine the RP2D and to assess the toxicity and preliminary antitumor activity of the PARP inhibitor, veliparib, in combination with carboplatin and paclitaxel. The combination was well-tolerated, with expected toxicities of myelosuppression, neuropathy, and gastrointestinal toxicity. The RP2D was determined to be paclitaxel 200 mg/m2 and carboplatin AUC 6 administered on day 3, and veliparib 100 mg PO bid on days 1-7 of a 21-day cycle. The administration of carboplatin and paclitaxel alone in cycle 1 allowed direct comparison with cycle 2 in which veliparib was added, in terms of PK and toxicity.

With any combination regimen, it is important to confirm that any new agent that is being combined with an existing therapeutic backbone do not affect the PK of that backbone therapy, thereby potentially impacting the efficacy and toxicity profile in patients. This could lead to false conclusions about the intended pharmacodynamic impact the new agent might have within the novel combination. Our studies have shown that veliparib PK was linear with dose and displayed PK parameter values as previously documented in this dose range. By day 3, the expected accumulation ratio based on observed half-life (ratio 1.20 for a 5.1 h half-life) or reported half-life (ratio 1.34 for a 6.1 h half-life) [34] was clearly not observed for Cmax, nor for AUC. Accurate determination of Cmax is difficult as it is dependent on the sampling frequency, but the less than expected accumulation ratio of AUC might suggest a small, clinically non-relevant impact of carboplatin and paclitaxel on veliparib PK, or this could merely be a spurious observation.

Paclitaxel exposure, as evaluated by Cmax and AUC, was not significantly impacted by veliparib. Likewise, carboplatin clearance was not significantly impacted by veliparib nor was carboplatin exposure, which suggests that veliparib did not meaningfully inhibit active creatinine secretion through inhibition of e.g. organic anion transporter 2 (OAT2), organic cation transporter 2 (OCT2), OCT3, multidrug and toxin extrusion protein 1 (MATE1), and MATE2-K [35]. Such an effect has been previously described for rucaparib and could be relevant for olaparib, and this would have resulted in falsely low estimates of creatinine clearance and a corresponding carboplatin underdosing of our patients [36,37]. Carboplatin AUC was targeted at an AUC of 6 mg•min/mL throughout the study, and despite the purported individualization of the carboplatin dose through applying the Cockcroft-Gault and Calvert equations, respectively, we observed significant bias and imprecision in the observed ultrafilterable carboplatin AUC relative to the target of 6 mg•min/mL. The potential reasons for these equations “missing the target” have been discussed previously [38] and include the Cockcroft-Gault formula derived in a biased sample of mostly male, all white patients with an R2 of 0.69, which is assumed to equal glomerular filtration rate [39]. This assumption ignores creatinine secretion and drugs that can inhibit that process [40]. The value from the Cockcroft-Gault formula is then imputed into the Calvert equation, which is derived in 31 mostly female patients with an R2 of 0.76 to calculate a carboplatin dose [41]. The calculated dose may be capped by the truncation of the glomerular filtration rate value at 125 mL/min [42], which is incorrectly assumed to be the physiological maximum [43].

Importantly, a clinically significant increase in myelosuppression was not observed in cycle 2 upon addition of veliparib when compared to cycle 1 with chemotherapy alone (Figure 2E-G and Supplementary Figure 1), although absolute neutrophil counts were lower on day 15 of cycle 2 vs cycle 1 (Supplemental Figure 1B; p=0.03), and there was a trend toward greater decrease in neutrophil count vs baseline in cycle 2 vs. cycle 1 (Supplementary Figure 1C). These data stand in sharp contrast to the significant myelosuppression seen with other combinations of PARP inhibitors plus cytotoxic agents. For example, a study of olaparib plus gemcitabine and cisplatin described greater myelosuppression than would be expected with the combination regimen alone [44]. A preliminary report of a study combining carboplatin and paclitaxel with olaparib observed enhanced myelotoxicity as well [45]. A study of olaparib and weekly paclitaxel in patients with metastatic breast cancer found an unexpectedly high degree of neutropenia, even with growth factor support [46]. A phase I study of veliparib plus the topoisomerase I inhibitor, topotecan, showed profound myelosuppression, with an MTD of 10 mg bid veliparib with topotecan at a dose of 0.6 mg on days 1-5 [47]. It is presently unclear why a similar degree of myelosuppression was not observed in the current study. One possibility is that inhibition of PARP was less complete at the doses of veliparib used in our present study when compared to the doses administered in the studies described above with veliparib and other PARP inhibitors. It is also conceivable that different chemotherapy regimens elicited varying degrees of PARP activation, which in turn, affected the impact of veliparib on the bone marrow. The exposure–toxicity relationship of paclitaxel has been described by threshold models. Because the time above a plasma concentration of 0.05 μM (Tc>0.05) predicts hematologic and non-hematologic toxicity, Joerger et al. [33] has suggested a therapeutic drug monitoring target of (Tc>0.05)=26-31 h. We therefore evaluated the ANC decrease of patients with (Tc>0.05) ≥31 h vs those with (Tc>0.05) <31 h. Interestingly, in the absence of veliparib, we were not able to detect a difference in ANC nadir as a function of the (Tc>0.05) cut-off. However, we were able to detect such a difference in the presence of veliparib, and the veliparib appeared to have a protective effect on patients with (Tc>0.05)<31h (Figure 2G). Of note, this was not corrected for multiple testing of the four groups of data, and the inability to detect an impact of (Tc>0.05) on ANC nadir in the absence of veliparib is reason for caution.

This phase 1 study investigated a novel schedule in which a PARP inhibitor was given on days 1-7 of a treatment cycle with the cytotoxic agents administered on day 3. The rationale for this schedule was to achieve significant PARP inhibition prior to the initiation of platinum-induced DNA damage. The 14-day break from PARP inhibition each cycle was designed to facilitate hematologic recovery. This schedule has been subsequently used in two disease-specific phase 2 studies. The first is a randomized study in patients with advanced NSCLC that compared carboplatin (AUC=6) plus paclitaxel (200 mg/m2) versus carboplatin, paclitaxel, and veliparib 120 mg bid (chemotherapy on day 3 and veliparib day 1-7 of a 21-day cycle) [48]. In this population of previously untreated patients, the triplet regimen was shown to have an acceptable safety profile, and a trend toward improved progression-free and overall survival was seen with the veliparib-containing arm. A phase 1 study of carboplatin, paclitaxel, and veliparib used this same schedule in Japanese patients with previously untreated non-small cell lung cancer also determined an MTD of 120 mg veliparib with carboplatin (AUC=6) plus paclitaxel (200 mg/m2) [49]. The BROCADE study randomized patients with metastatic breast cancer and a deleterious BRCA1 or BRCA2 to veliparib (40 mg bid days 1-7) plus temozolamide (days 1-5) versus veliparib (120 mg bid days 1-7) plus carboplatin (AUC=6) and paclitaxel (175 mg/m2) versus carboplatin, paclitaxel and placebo [50]. Up to 2 prior lines of cytotoxic therapy for metastatic disease were allowed in this particular study. Han et al. reported no significant increase in toxicity when veliparib was combined with carboplatin plus paclitaxel. With respect to clinical efficacy, veliparib was associated with a significantly improved response rate and a trend toward favorable progression-free and overall survival when compared to placebo. Based on the positive results of this study, a larger randomized phase III clinical trial is underway (NCT02163694).

In summary, this phase 1 study established a RP2D for the PARP inhibitor, veliparib, in combination with carboplatin and paclitaxel in patients with advanced solid tumors. Importantly, myelosuppression and other toxicities were not significantly increased with the triplet combination. The schedule developed in this phase 1 study has been well-tolerated in subsequent phase 2 studies in NSCLC and breast cancer. Promising clinical activity was observed, and this regimen is now being developed in specific tumor types .

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEGEMENTS

The authors would like to express their sincere thanks to the patients and their family members who were enrolled on this study. The authors would also like to thank the clinical research staff who were actively involved in the conduct of this study.

Financial Support: The study was supported in part by the following grants: NIH/NCI UM1-CA186690, NIH/NCI U01-CA099168. This project used the UPMC Hillman Cancer Pharmacokinetics and Pharmacodynamics Facility (CPPF), Biostatistics Facility (BF), and Clinical Research Services (CRS), and was supported in part by award NIH/NCI P30-CA47904.

Footnotes

Conflict of Interest: None

Publisher's Disclaimer: This Author Accepted Manuscript is a PDF file of an unedited peer-reviewed manuscript that has been accepted for publication but has not been copyedited or corrected. The official version of record that is published in the journal is kept up to date and so may therefore differ from this version.

REFERENCES

- 1.Ray Chaudhuri A, Nussenzweig A (2017) The multifaceted roles of PARP1 in DNA repair and chromatin remodelling. Nature Reviews Molecular Cell Biology 18:610. doi: 10.1038/nrm.2017.53 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bryant HE, Schultz N, Thomas HD, Parker KM, Flower D, Lopez E, Kyle S, Meuth M, Curtin NJ, Helleday T (2005) Specific killing of BRCA2-deficient tumours with inhibitors of poly(ADP-ribose) polymerase. Nature 434 (7035):913–917. doi:nature03443 [pii] 10.1038/nature03443 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Farmer H, McCabe N, Lord CJ, Tutt AN, Johnson DA, Richardson TB, Santarosa M, Dillon KJ, Hickson I, Knights C, Martin NM, Jackson SP, Smith GC, Ashworth A (2005) Targeting the DNA repair defect in BRCA mutant cells as a therapeutic strategy. Nature 434 (7035):917–921 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Moynahan ME, Chiu JW, Koller BH, Jasin M (1999) Brca1 controls homology-directed DNA repair. Mol Cell 4 (4):511–518 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Moynahan ME, Pierce AJ, Jasin M (2001) BRCA2 is required for homology-directed repair of chromosomal breaks. Mol Cell 7 (2):263–272 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bieche I, De Murcia G, Lidereau R (1996) Poly (ADP-ribose) polymerase gene expression status and genomic instability in human breast cancer. Clinical cancer research 2 (7): 1163–1167 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Molloy-Simard V, St-Laurent J-F, Vigneault F, Gaudreault M, Dargis N, Guérin M-C, Leclerc S, Morcos M, Black D, Molgat Y, Bergeron D, de Launoit Y, Boudreau F, Desnoyers S, Guérin S (2012) Altered Expression of the Poly(ADP-Ribosyl)ation Enzymes in Uveal Melanoma and Regulation of PARG Gene Expression by the Transcription Factor ERM. Investigative Ophthalmology & Visual Science 53 (10):6219–6231. doi: 10.1167/iovs.11-8853 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ossovskaya V, Koo IC, Kaldjian EP, Alvares C, Sherman BM (2010) Upregulation of Poly (ADP-Ribose) Polymerase-1 (PARP1) in Triple-Negative Breast Cancer and Other Primary Human Tumor Types. Genes & cancer 1 (8):812–821. doi: 10.1177/1947601910383418 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Salemi M, Galia A, Fraggetta F, La Corte C, Pepe P, La Vignera S, Improta G, Bosco P, Calogero AE (2013) Poly (ADP-ribose) polymerase 1 protein expression in normal and neoplastic prostatic tissue. European journal of histochemistry : EJH 57 (2):e13. doi: 10.4081/ejh.2013.e13 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Sulzyc-Bielicka V, Domagala P, Hybiak J, Majewicz-Broda A, Safranow K, Domagala W (2012) Colorectal cancers differ in respect of PARP-1 protein expression. Polish journal of pathology : official journal of the Polish Society of Pathologists 63 (2):87–92 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Klauschen F, von Winterfeld M, Stenzinger A, Sinn BV, Budczies J, Kamphues C, Bahra M, Wittschieber D, Weichert W, Striefler J, Riess H, Dietel M, Denkert C (2012) High nuclear poly-(ADP-ribose)-polymerase expression is prognostic of improved survival in pancreatic cancer. Histopathology 61 (3):409–416. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2559.2012.04225.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Galia A, Calogero AE, Condorelli R, Fraggetta F, La Corte A, Ridolfo F, Bosco P, Castiglione R, Salemi M (2012) PARP-1 protein expression in glioblastoma multiforme. European journal of histochemistry : EJH 56 (1):e9. doi: 10.4081/ejh.2012.e9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Calabrese CR, Almassy R, Barton S, Batey MA, Calvert AH, Canan-Koch S, Durkacz BW, Hostomsky Z, Kumpf RA, Kyle S, Li J, Maegley K, Newell DR, Notarianni E, Stratford IJ, Skalitzky D, Thomas HD, Wang LZ, Webber SE, Williams KJ, Curtin NJ (2004) Anticancer chemosensitization and radiosensitization by the novel poly(ADP-ribose) polymerase-1 inhibitor AG14361. Journal of the National Cancer Institute 96 (1):56–67 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Horton JK, Wilson SH (2013) Strategic Combination of DNA-Damaging Agent and PARP Inhibitor Results in Enhanced Cytotoxicity. Frontiers in oncology 3:257. doi: 10.3389/fonc.2013.00257 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Chen A (2011) PARP inhibitors: its role in treatment of cancer. Chinese journal of cancer 30 (7):463–471. doi: 10.5732/cjc.011.10111 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Huggins-Puhalla S, Beumer JH, Appleman LJ, Tawbi HA, Stoller RG, Lin Y, Kiesel B, Tan AR, Gibbon D, Jiang Y, Garcia A, Chew HK, Morgan R, Shepherd SP, Giranda VL, Chen AP, Belani CP, Chu E (2012) A phase I study of chronically dosed, single-agent veliparib (ABT-888) in patients (pts) with either BRCA 1/2-mutated cancer (BRCA+), platinum-refractory ovarian cancer, or basal-like breast cancer (BRCA-wt). J Clinical Oncol 30 (Supplement):Abstr 3054 [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kaufman B, Shapira-Frommer R, Schmutzler RK, Audeh MW, Friedlander M, Balmana J, Mitchell G, Fried G, Stemmer SM, Hubert A, Rosengarten O, Steiner M, Loman N, Bowen K, Fielding A, Domchek SM (2015) Olaparib monotherapy in patients with advanced cancer and a germline BRCA1/2 mutation. J Clin Oncol 33 (3):244–250. doi: 10.1200/jco.2014.56.2728 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Tutt A, Robson M, Garber JE, Domchek SM, Audeh MW, Weitzel JN, Friedlander M, Arun B, Loman N, Schmutzler RK, Wardley A, Mitchell G, Earl H, Wickens M, Carmichael J (2010) Oral poly(ADP-ribose) polymerase inhibitor olaparib in patients with BRCA1 or BRCA2 mutations and advanced breast cancer: a proof-of-concept trial. Lancet 376 (9737):235–244. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(10)60892-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Mateo J, Carreira S, Sandhu S, Miranda S, Mossop H, Perez-Lopez R, Nava Rodrigues D, Robinson D, Omlin A, Tunariu N, Boysen G, Porta N, Flohr P, Gillman A, Figueiredo I, Paulding C, Seed G, Jain S, Ralph C, Protheroe A, Hussain S, Jones R, Elliott T, McGovern U, Bianchini D, Goodall J, Zafeiriou Z, Williamson CT, Ferraldeschi R, Riisnaes R, Ebbs B, Fowler G, Roda D, Yuan W, Wu YM, Cao X, Brough R, Pemberton H, A'Hern R, Swain A, Kunju LP, Eeles R, Attard G, Lord CJ, Ashworth A, Rubin MA, Knudsen KE, Feng FY, Chinnaiyan AM, Hall E, de Bono JS (2015) DNA-Repair Defects and Olaparib in Metastatic Prostate Cancer. N Engl J Med 373 (18): 1697–1708. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1506859 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Michels J, Vitale I, Senovilla L, Enot DP, Garcia P, Lissa D, Olaussen KA, Brenner C, Soria JC, Castedo M, Kroemer G (2013) Synergistic interaction between cisplatin and PARP inhibitors in non-small cell lung cancer. Cell cycle (Georgetown, Tex 12 (6):877–883. doi: 10.4161/cc.24034 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Rottenberg S, Jaspers JE, Kersbergen A, van der Burg E, Nygren AO, Zander SA, Derksen PW, de Bruin M, Zevenhoven J, Lau A, Boulter R, Cranston A, O'Connor MJ, Martin NM, Borst P, Jonkers J (2008) High sensitivity of BRCA1-deficient mammary tumors to the PARP inhibitor AZD2281 alone and in combination with platinum drugs. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 105 (44): 17079–17084. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0806092105 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Hastak K, Alli E, Ford JM (2010) Synergistic chemosensitivity of triple-negative breast cancer cell lines to poly(ADP-Ribose) polymerase inhibition, gemcitabine, and cisplatin. Cancer Res 70 (20):7970–7980. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.can-09-4521 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Middleton MR, Friedlander P, Hamid O, Daud A, Plummer R, Falotico N, Chyla B, Jiang F, McKeegan E, Mostafa NM, Zhu M, Qian J, McKee M, Luo Y, Giranda VL, McArthur GA (2015) Randomized phase II study evaluating veliparib (ABT-888) with temozolomide in patients with metastatic melanoma. Ann Oncol 26 (10):2173–2179. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdv308 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Pietanza MC, Waqar SN, Krug LM, Dowlati A, Hann CL, Chiappori A, Owonikoko TK, Woo KM, Cardnell RJ, Fujimoto J, Long L, Diao L, Wang J, Bensman Y, Hurtado B, de Groot P, Sulman EP, Wistuba II, Chen A, Fleisher M, Heymach JV, Kris MG, Rudin CM, Byers LA (2018) Randomized, Double-Blind, Phase II Study of Temozolomide in Combination With Either Veliparib or Placebo in Patients With Relapsed-Sensitive or Refractory Small-Cell Lung Cancer. J Clin Oncol 36 (23):2386–2394. doi: 10.1200/jco.2018.77.7672 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kummar S, Ji J, Morgan R, Lenz HJ, Puhalla SL, Belani CP, Gandara DR, Allen D, Kiesel B, Beumer JH, Newman EM, Rubinstein L, Chen A, Zhang Y, Wang L, Kinders RJ, Parchment RE, Tomaszewski JE, Doroshow JH (2012) A phase I study of veliparib in combination with metronomic cyclophosphamide in adults with refractory solid tumors and lymphomas. Clin Cancer Res 18 (6):1726–1734. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.ccr-11-2821 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Belani CP, Kearns CM, Zuhowski EG, Erkmen K, Hiponia D, Zacharski D, Engstrom C, Ramanathan RK, Capozzoli MJ, Aisner J, Egorin MJ (1999) Phase I trial, including pharmacokinetic and pharmacodynamic correlations, of combination paclitaxel and carboplatin in patients with metastatic non-small-cell lung cancer. Journal of clinical oncology : official journal of the American Society of Clinical Oncology 17 (2):676–684 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Therasse P, Arbuck SG, Eisenhauer EA, Wanders J, Kaplan RS, Rubinstein L, Verweij J, Van Glabbeke M, van Oosterom AT, Christian MC, Gwyther SG (2000) New Guidelines to Evaluate the Response to Treatment in Solid Tumors. Journal of the National Cancer Institute 92 (3):205–216. doi: 10.1093/jnci/92.3.205 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Parise RA, Shawaqfeh M, Egorin MJ, Beumer JH (2008) Liquid chromatography-mass spectrometric assay for the quantitation in human plasma of ABT-888, an orally available, small molecule inhibitor of poly(ADP-ribose) polymerase. J Chromatogr B Analyt Technol Biomed Life Sci 872 (1-2): 141–147. doi: 10.1016/j.jchromb.2008.07.032 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Colville H, Dzadony R, Kemp R, Stewart S, Zeh HJ 3rd, Bartlett DL, Holleran J, Schombert K, Kosovec JE, Egorin MJ, Beumer JH (2010) In vitro circuit stability of 5-fluorouracil and oxaliplatin in support of hyperthermic isolated hepatic perfusion. The journal of extra-corporeal technology 42 (1):75–79 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Parise RA, Ramanathan RK, Zamboni WC, Egorin MJ (2003) Sensitive liquid chromatography-mass spectrometry assay for quantitation of docetaxel and paclitaxel in human plasma. J Chromatogr B Analyt Technol Biomed Life Sci 783 (1):231–236 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Sheiner LB, Beal SL (1981) Some suggestions for measuring predictive performance. Journal of pharmacokinetics and biopharmaceutics 9 (4):503–512 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Joerger M, Kraff S, Jaehde U, Hilger RA, Courtney JB, Cline DJ, Jog S, Baburina I, Miller MC, Salamone SJ (2017) Validation of a Commercial Assay and Decision Support Tool for Routine Paclitaxel Therapeutic Drug Monitoring (TDM). Therapeutic drug monitoring 39 (6):617–624. doi: 10.1097/ftd.0000000000000446 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Joerger M, von Pawel J, Kraff S, Fischer JR, Eberhardt W, Gauler TC, Mueller L, Reinmuth N, Reck M, Kimmich M, Mayer F, Kopp HG, Behringer DM, Ko YD, Hilger RA, Roessler M, Kloft C, Henrich A, Moritz B, Miller MC, Salamone SJ, Jaehde U (2016) Open-label, randomized study of individualized, pharmacokinetically (PK)-guided dosing of paclitaxel combined with carboplatin or cisplatin in patients with advanced non-small-cell lung cancer (NSCLC). Ann Oncol 27 (10):1895–1902. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdw290 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Salem AH, Giranda VL, Mostafa NM (2014) Population pharmacokinetic modeling of veliparib (ABT-888) in patients with non-hematologic malignancies. Clin Pharmacokinet 53 (5):479–488. doi: 10.1007/s40262-013-0130-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Nakada T, Kudo T, Kume T, Kusuhara H, Ito K (2018) Quantitative analysis of elevation of serum creatinine via renal transporter inhibition by trimethoprim in healthy subjects using physiologically-based pharmacokinetic model. Drug metabolism and pharmacokinetics 33 (1): 103–110. doi: 10.1016/j.dmpk.2017.11.314 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.US Dept of Health and Human Services FaDA, Center for Drug Evaluation and Research, (2016) Rucaparib: Multidiscipline Review Summary; https://wwwaccessdatafdagov/drugsatfda_docs/nda/2016/209115Orig1s000MultiDisciplineRpdf (April 20, 2019) [Google Scholar]

- 37.McCormick A, Swaisland H (2017) In vitro assessment of the roles of drug transporters in the disposition and drug-drug interaction potential of olaparib. Xenobiotica; the fate of foreign compounds in biological systems 47 (10):903–915. doi: 10.1080/00498254.2016.1241449 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Beumer JH, Inker LA, Levey AS (2018) Improving Carboplatin Dosing Based on Estimated GFR. Am J Kidney Dis 71 (2): 163–165. doi: 10.1053/j.ajkd.2017.10.005 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Cockcroft DW, Gault MH (1976) Prediction of creatinine clearance from serum creatinine. Nephron 16 (1):31–41. doi: 10.1159/000180580 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.German P, Liu HC, Szwarcberg J, Hepner M, Andrews J, Kearney BP, Mathias A (2012) Effect of cobicistat on glomerular filtration rate in subjects with normal and impaired renal function. Journal of acquired immune deficiency syndromes (1999) 61 (1):32–40. doi: 10.1097/QAI.0b013e3182645648 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Calvert AH, Newell DR, Gumbrell LA, O'Reilly S, Burnell M, Boxall FE, Siddik ZH, Judson IR, Gore ME, Wiltshaw E (1989) Carboplatin dosage: prospective evaluation of a simple formula based on renal function. J Clin Oncol 7 (11): 1748–1756. doi: 10.1200/jco.1989.7.11.1748 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Fehr M, Maranta AF, Reichegger H, Gillessen S, Cathomas R (2018) Carboplatin dose based on actual renal function: no excess of acute haematotoxicity in adjuvant treatment in seminoma stage I. ESMO open 3 (3):e000320. doi: 10.1136/esmoopen-2018-000320 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Wesson L (1969) Physiology of the Human Kidney Grune and Stratton, New York, NY [Google Scholar]

- 44.Rajan A, Carter CA, Kelly RJ, Gutierrez M, Kummar S, Szabo E, Yancey MA, Ji J, Mannargudi B, Woo S, Spencer S, Figg WD, Giaccone G (2012) A phase I combination study of olaparib with cisplatin and gemcitabine in adults with solid tumors. Clin Cancer Res 18 (8):2344–2351. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-11-2425 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.van der Noll R, Ang J, Jager A, Marchetti S, Mergui-Roelvink M, De Bono J, Lolkema M, Brunetto A, Arkenau H, De Jonge M, van der Biessen D, Tchakov I, Bowen K, Schellens J (2013) Phase I study of olaparib in combinatio with carboplatin and/or paclitaxel in patients with advanced solid tumors. J Clin Oncol 31:(suppl; abstr 2579) [Google Scholar]

- 46.Dent RA, Lindeman GJ, Clemons M, Wildiers H, Chan A, McCarthy NJ, Singer CF, Lowe ES, Watkins CL, Carmichael J (2013) Phase I trial of the oral PARP inhibitor olaparib in combination with paclitaxel for first- or second-line treatment of patients with metastatic triple-negative breast cancer. Breast Cancer Res 15 (5):R88. doi: 10.1186/bcr3484 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Kummar S, Chen A, Ji J, Zhang Y, Reid JM, Ames M, Jia L, Weil M, Speranza G, Murgo AJ, Kinders R, Wang L, Parchment RE, Carter J, Stotler H, Rubinstein L, Hollingshead M, Melillo G, Pommier Y, Bonner W, Tomaszewski JE, Doroshow JH (2011) Phase I study of PARP inhibitor ABT-888 in combination with topotecan in adults with refractory solid tumors and lymphomas. Cancer Res 71 (17):5626–5634. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.can-11-1227 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Ramalingam SS, Blais N, Mazieres J, Reck M, Jones CM, Juhasz E, Urban L, Orlov S, Barlesi F, Kio E, Keiholz U, Qin Q, Qian J, Nickner C, Dziubinski J, Xiong H, Ansell P, McKee M, Giranda V, Gorbunova V (2017) Randomized, Placebo-Controlled, Phase II Study of Veliparib in Combination with Carboplatin and Paclitaxel for Advanced/Metastatic Non-Small Cell Lung Cancer. Clin Cancer Res 23 (8): 1937–1944. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.ccr-15-3069 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Mizugaki H, Yamamoto N, Nokihara H, Fujiwara Y, Horinouchi H, Kanda S, Kitazono S, Yagishita S, Xiong H, Qian J, Hashiba H, Shepherd SP, Giranda V, Tamura T (2015) A phase 1 study evaluating the pharmacokinetics and preliminary efficacy of veliparib (ABT-888) in combination with carboplatin/paclitaxel in Japanese subjects with non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC). Cancer chemotherapy and pharmacology 76 (5):1063–1072. doi: 10.1007/s00280-015-2876-7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Han HS, Dieras V, Robson M, Palacova M, Marcom PK, Jager A, Bondarenko I, Citrin D, Campone M, Telli ML, Domchek SM, Friedlander M, Kaufman B, Garber JE, Shparyk Y, Chmielowska E, Jakobsen EH, Kaklamani V, Gradishar W, Ratajczak CK, Nickner C, Qin Q, Qian J, Shepherd SP, Isakoff SJ, Puhalla S (2018) Veliparib with temozolomide or carboplatin/paclitaxel versus placebo with carboplatin/paclitaxel in patients with BRCA1/2 locally recurrent/metastatic breast cancer: randomized phase II study. Ann Oncol 29 (1): 154–161. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdx505 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.