Abstract

Background

Improved genetic understanding of Mycobacterium tuberculosis (MTB) resistance to novel and repurposed anti-tubercular agents can aid the development of rapid molecular diagnostics.

Methods

Adhering to PRISMA guidelines, in March 2018, we performed a systematic review of studies implicating mutations in resistance through sequencing and phenotyping before and/or after spontaneous resistance evolution, as well as allelic exchange experiments. We focused on the novel drugs bedaquiline, delamanid, pretomanid and the repurposed drugs clofazimine and linezolid. A database of 1373 diverse control MTB whole genomes, isolated from patients not exposed to these drugs, was used to further assess genotype–phenotype associations.

Results

Of 2112 papers, 54 met the inclusion criteria. These studies characterized 277 mutations in the genes atpE, mmpR, pepQ, Rv1979c, fgd1, fbiABC and ddn and their association with resistance to one or more of the five drugs. The most frequent mutations for bedaquiline, clofazimine, linezolid, delamanid and pretomanid resistance were atpE A63P, mmpR frameshifts at nucleotides 192–198, rplC C154R, ddn W88* and ddn S11*, respectively. Frameshifts in the mmpR homopolymer region nucleotides 192–198 were identified in 52/1373 (4%) of the control isolates without prior exposure to bedaquiline or clofazimine. Of isolates resistant to one or more of the five drugs, 59/519 (11%) lacked a mutation explaining phenotypic resistance.

Conclusions

This systematic review supports the use of molecular methods for linezolid resistance detection. Resistance mechanisms involving non-essential genes show a diversity of mutations that will challenge molecular diagnosis of bedaquiline and nitroimidazole resistance. Combined phenotypic and genotypic surveillance is needed for these drugs in the short term.

Introduction

TB is among the top 10 causes of death worldwide and the most lethal infectious disease.1 The TB epidemic is complicated by the evolution of drug resistance, estimated in 2018 at 420 000–560 000 new cases.1 The majority of these cases are MDR and their treatment requires a second-line drug regimen for 9–24 months, with significant toxicity and high rates of failure. The use of the novel or repurposed drugs bedaquiline, clofazimine, linezolid, delamanid and pretomanid holds considerable promise for shortening MDR- and XDR-TB therapy and improving patient outcomes. However, data to guide the optimal clinical use of these agents in combination with other drugs to minimize the risk of resistance acquisition is still emerging.2,3 In addition, resistance surveillance and testing in clinical laboratories has been complicated by difficulties in securing these compounds for testing as well as the lack of standardization of testing concentrations and procedures.4

In many parts of the world, there are significant limitations in capacity for mycobacterial culture. The success of molecular diagnostics such as the Xpert MTB/RIF for detecting rifampicin resistance through the detection of mutations in the RNA polymerase subunit β gene, rpoB, has encouraged researchers to seek similar genetic markers for resistance to other agents. WGS is also increasingly being employed as a resistance diagnostic in well-resourced public health agencies.5,6 However, the genetic determinants of resistance are only well understood for a subset of anti-tubercular agents and resistance to the novel and repurposed agents remains the least understood.

Evidence suggests that both clofazimine and bedaquiline target the electron transport chain of Mycobacterium tuberculosis (MTB).7 Clofazimine was originally discovered as an anti-tubercular agent in the 1950s and is commonly used in the treatment of leprosy.8 The exact mechanism of action of clofazimine remains unknown, but it appears to have multiple effects on MTB, including interference with redox cycling involving the enzymatic reduction of clofazimine by NDH-2, generating bactericidal reactive oxygen species, as well as membrane destabilization and dysfunction.7,9,10 Bedaquiline, the first novel anti-tubercular agent approved by the US FDA in 40 years, inhibits ATP synthase by binding to subunit C, starving the bacteria of ATP.7,11,12

Linezolid, an oxazolidinone, is licensed for the treatment of serious skin and soft tissue infections, bacteraemia and pneumonia caused by Gram-positive bacteria. It kills MTB by binding and blocking tRNA in the peptidyltransferase centre on the 50S ribosomal subunit, which includes 5S rRNA and 23S rRNA.13–15

Delamanid was given conditional approval by the EMA in 2014, pending ongoing clinical trials, whereas pretomanid received approval in 2019 by the FDA for treatment of pulmonary XDR-TB and non-responsive MDR-TB.16,17 Both nitroimidazoles impair the biosynthesis of methoxy- and keto-mycolic acids, which are components of the mycobacterial cell wall.16 Both compounds are prodrugs that are reductively activated by a deazaflavin (F420)-dependent nitroreductase (Ddn).16

To summarize the evidence implicating specific genes and mutations in resistance to the five aforementioned drugs, we conducted a systematic review and meta-analysis of the literature. We aimed to establish both strong causal and associative relationships for these agents. Although allelic exchange experiments most directly establish causal mutation–phenotype relationships, data from these types of experiments are rarely available.17 As a result, we include data from both in vitro and clinical isolates that evolved new mutations coinciding with phenotypic resistance to one of the five agents above, as consistent with a strong association. We also include surveys of mutations and phenotypic resistance among clinical isolates. Although the latter type of evidence is least helpful in establishing causality, the frequency of mutations among susceptible and resistant isolates are relevant to catalogue and can support evidence gathered from spontaneous evolution.

Materials and methods

Definitions

Non-synonymous substitutions were denoted by x#y, where x represents the WT amino acid, # the codon number and y the variant amino acid; rRNA and non-coding (promoter or intergenic regions) nucleotide substitutions were denoted by x#y, where # refers to the nucleotide position relative to the start of the region, x is the WT nucleotide base and y is the variant nucleotide base. We used the asterisk symbol to indicate a stop codon. For insertions and deletions, the notation was ins x# or del x# where the x was the base or bases deleted or inserted and # is the nucleotide position after which the insertion occurred or the position of the deleted base(s). For phenotype measurements, we report MIC, 90% inhibitory concentration (IC90) or inhibition at a single tested concentration as available from the manuscript.18 MIC changes were considered ‘modest’ if they were lower than 8× the parent MIC (prior to drug selection), where available, or lower than 8× the epidemiological cut-off (ECOFF). Mutations found in two or more isolates from two papers or three or more isolates from the same paper are elaborated in the main text tables. All mutations are detailed in the Supplementary data (available at JAC Online).

Literature search

We combined the search terms listed in Table 1 to identify peer-reviewed primary research studies of MTB resistance mutations to each of the five drugs of interest. Searches were conducted for each drug separately, even for drugs sharing at least one resistance mechanism. The results were combined only after search, inclusion and review. We searched each of the following four databases: PubMed, EMBASE, Scopus and Web of Science in March 2018 and did not filter by publication date or language.

Table 1.

Search strategy to identify studies of mutations documented to confer resistance to each drug

| Database search theme |

|||

|---|---|---|---|

| (1) Organism | (2) Drug resistance | (3) Mutation | |

| Text terms | (1) ‘Tuberculosis’ OR ‘M. Tb’ OR ‘MTB’ | (1) ‘resistant’ OR ‘resistance’ OR ‘MIC’ OR ‘drug susceptibility’ |

(1) ‘mutation’ OR (2) ‘genetic’ OR (3) ‘mutagenesis’ OR (4) ‘mutant’ OR (5) ‘frameshift’ OR (6) ‘codon’ OR (7) ‘nonsense’ OR (8) ‘missense’ OR (9) ‘transduction’ OR (10) ‘amino acid substitution’ OR (11) ‘sequencing’ OR (12) ‘whole genome’ OR (13) ‘Sanger’ OR (14) ‘Illumina’ OR (15) ‘allelic exchange’ |

Inclusion criteria

A study was included if it met one or more of the following study type categories: (i) targeted sequencing or WGS was performed on clinical MTB isolates resistant to any of the five drugs; (ii) targeted sequencing or WGS was performed on in vitro-evolved MTB isolates that spontaneously developed resistance to any of the five drugs; (iii) mutations within a putative resistance gene were introduced into MTB strains using allelic exchange, transduction or site-directed/in vitro mutagenesis.

We also required all studies to meet the following methodological criteria: (i) gene sequencing or WGS was performed after or before and after resistance evolution or genetic alteration; (ii) drug susceptibility or MIC testing was performed after or before and after resistance evolution or genetic alteration.

Studies with phenotype and genotype available before and after resistance evolution were considered higher confidence than those reporting these measurements only on resistant isolates. The latter were labelled ‘low confidence’ in the summary tables.

Exclusion criteria

We excluded manuscripts that: (i) studied mycobacterial species other than MTB; (ii) only created knockout or overexpression of a gene instead of a single point mutation; and (iii) did not state how the unique transfer of the intended point mutation was confirmed.

Data extraction

Study abstracts and full-text manuscripts were reviewed by two authors independently for inclusion (N.K. and H.Z.) and one additional author (M.F.) adjudicated differences between them. From each publication, the following information was extracted: authors, publication year, gene, amino acid and nucleotide coordinates of the mutation, host strain, method used to introduce the mutation, method used to confirm introduction of the mutation if applicable; method for resistance phenotype determination and result, sequencing method and result, and genetic data accession numbers.

Clinical isolate database

Genomes from a previous study on quantitative resistance (n = 1373) all collected prior to the end of 2012 were used in this study as they originated from clinical settings without prior use of bedaquiline, clofazimine, delamanid, pretomanid and linezolid.19 The majority of isolates were from Peru, where clofazimine was introduced for MDR/XDR-TB treatment in February 2016. Isolates were cultured and DNA was extracted from cultured bacterial cells and then subjected to Illumina sequencing as previously described.19 Illumina reads were trimmed using PRINSEQ, setting the average phred score threshold to 20.20 Raw read data were processed according to a validated pipeline with modification, as described below.21 Reads were confirmed to belong to MTB complex using Kraken and all isolates had >90% mapping.22 Reads were aligned to H37Rv (GenBank NC000962.3) reference genome using BWA MEM.23 Duplicate reads were removed using PICARD.24 All isolates had coverage at ≥95% of known drug resistance regions (katG, inhA and its promoter, rpoB, embA, embB, embC and embB promoter, ethA, gyrA and gyrB, rrs, rpsL, gid, pncA, rpsA and eis promoter) at 10× or higher. Variants were called using Pilon, which uses local assembly to increase insertions and deletion (indel) call accuracy.25 This deviates from Ezewudo et al.,21 who used SAMtools for variant calling. The reference allele was implied if allele frequency was <75% or the Pilon filter was not PASS. Lineage determination was using a 92 SNP modified barcode that included all SNPs from Coll et al., 2014.26

A subset of the isolates underwent MIC testing with linezolid on 7H10 medium at 0.25, 0.5, 1, 2, 3, 4, 6, 8 and 10 mg/L.18 The WHO ECOFF of 1 mg/L was used as the breakpoint to define linezolid resistance.27 A different subset underwent clofazimine MIC testing on 7H10 at 0.5, 1 and 2 mg/L.28 As the evidence reviewed by WHO in 2018 was deemed insufficient to propose an ECOFF for clofazimine on 7H10, we defined a tentative ECOFF of 1 mg/L based on the shape of the MIC distribution from this dataset.27

Results

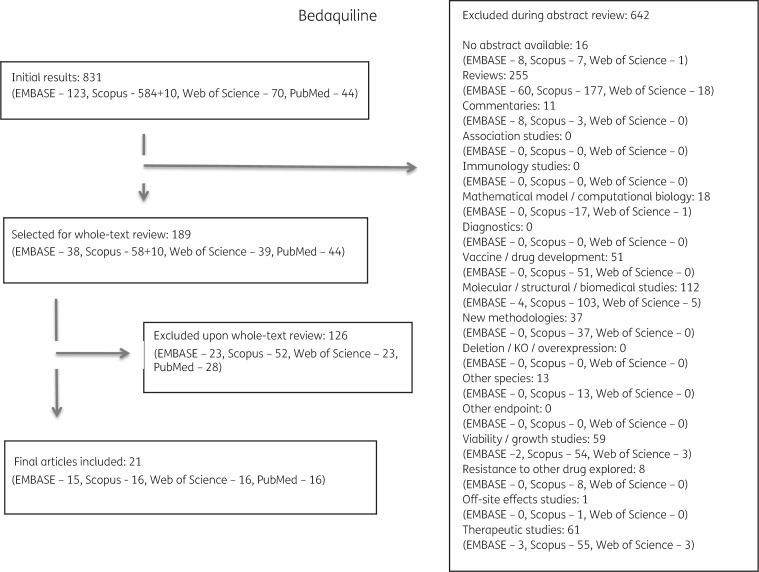

Of the 2112 publications identified, 1458 met one or more exclusion criteria after abstract review and 479 met exclusion criteria after full review. Duplicates or papers describing the same isolates were combined. In total, 54 articles were selected for inclusion and final data extraction (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Study selection process performed for bedaquiline and reasons for exclusion of studies. The same selection process was performed for all five drugs (see Figures S1 to S4).

Bedaquiline and clofazimine

Seventeen studies examined 86 different putative bedaquiline resistance mutations in the genes atpE, mmpR (Rv0678) and Rv2535c (pepQ) (Table S1) and 10 studies examined 56 clofazimine mutations in the genes mmpR, Rv1979c and pepQ (Table S2). Seven studies reported on resistance to both drugs.9,11,29–48

Mutations associated with bedaquiline and clofazimine resistance

mmpR This gene encodes a 165 amino acid (aa) non-essential transcriptional repressor thought to affect bedaquiline and clofazimine efflux via the mmpS5-mmpL5 pump.40

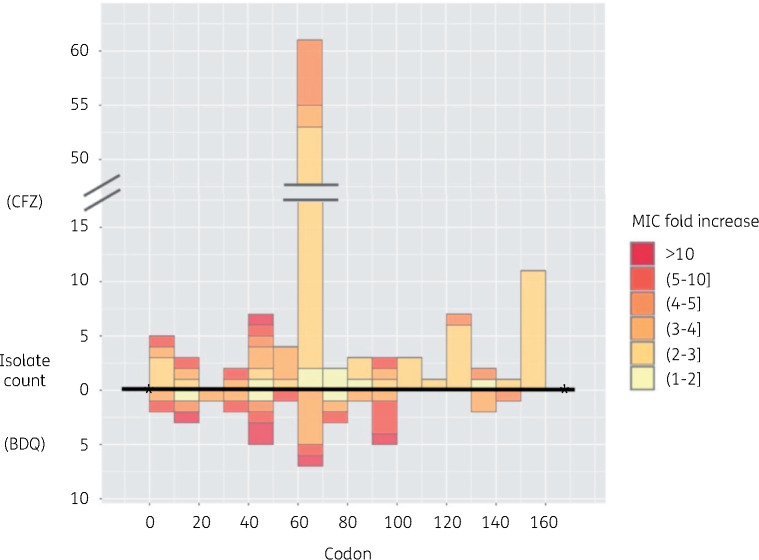

Mutational spectrum Twelve studies identified 66 unique mmpR mutations that were widely distributed between codon positions 1 and 145 with a similar distribution for bedaquiline and clofazimine (Figure 2).9,32–36,38,39,41,42,44–48 Mutations were individually rare, with none reported by more than three studies. The most frequent mutations associated with resistance were frameshifts in the 6-guanine homopolymer at nt192–198 (11 isolates for bedaquiline and 45 for clofazimine) or low sequence complexity regions at nt138–144 (seven isolates for bedaquiline and two for clofazimine) or nt212–216 (four isolates for bedaquiline and two for clofazimine) (Tables 2, 3, S1 and S2). Mixed mutations at these positions were common (Tables S1 and S2).

Figure 2.

Mutations in mmpR with relative MIC fold changes for bedaquiline (BDQ) or clofazimine (CFZ). Round and square brackets are used as exclusive and inclusive of the listed concentration, respectively. This figure appears in colour in the online version of JAC and in black and white in the print version of JAC.

Table 2.

Mutations associated with resistance to bedaquiline (BDQ) in ≥2 isolates reported by ≥2 studies or ≥3 isolates reported by ≥1 studya

| Gene | aa change | MIC summary (relative to parent for available isolates) | MIC change by mutant/study | Data summary | References (in order of data in column 4 and separated by semicolons)b |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| atpE | D28V or P or G or N | 4–17× | 16× (D28V), 10× (D28P); 17× (5 isolates with D28G); 4× (D28N) | 7 in vitro spontaneous mutants, 1 clinical resistance evolution (D28N) | Huitric 2010;30+ Segala 2012;31+ Zimenkov 201739 |

| atpE | E61D | 8–33× | 16× (3 isolates), 8×, 32×; 16×, 33× | 7 in vitro spontaneous mutants | Huitric 2010,30+ Segala 201231+ |

| atpE | A63P or V | 4–133× | ≥4×; 64–128×; 133×; 7H9 MIC80 ≥5.6 mg/L; 4–8×; 5×(A63V) | 11cin vitro spontaneous mutants, 1 clinical resistance evolution (A63V) | Petrella 2006;29+ Huitric 2010;30+ Segala 2012;31+ Tantry 2016,372017;43+ Andries 2005;11+ Zimenkov 201739 |

| atpE | I66M or V | 4–64× | ≥4×; 16×; 33×; 64×; 7H9 MIC80 ≥5.6 mg/L; MIC 0.125 mg/L (I66V) | 10cin vitro spontaneous mutants, 1 clinical isolate with higher MIC (I66V) | Petrella 2006;29+ Huitric 2010;30+ Segala 2012;31+ Andries 2014;33+ Tantry 2016,372017;43+ Martinez 201846+ |

| Rv0678 | V1A (M1A) | 8–10× | 8×; 10× | 2 clinical resistance evolution | Bloemberg 2015;35+ Hoffman 201636+ |

| Rv0678 | W42R | 2× | 2×; 7H11 MIC 0.12 mg/L | 1 clinical resistance evolution; 1 clinical isolate with higher MIC | Andries 2014;33+ Villellas 201744 |

| Rv0678 | frameshifts nt138–144 | 4–16× | 16× (ins C141–142); 8× (ins G139), 4× (ins C144 mixed), 7H11 MIC 0.12–0.25 mg/L (1 isolate with ins G139, 1 mixed with other Rv0678 mutations); 7H11 MIC 0.25 mg/L (ins G140); MIC 0.25 mg/L (D47fs) | 3 clinical resistance evolution (ins C141, ins C144, ins G139), 4dclinical isolates with higher MIC | Andries 2014;33+ Zimenkov 2017;39Veziris 2017;45Martinez 201846+ |

| Rv0678 | S53L or P | ≥0.25 mg/L | MIC 0.25–0.5 mg/L (S53P in 3 isolates and S53L in 2 isolates, unknown parent, MIC breakpoint for BDQ resistance 0.25 mg/L) | 5 clinical strains | Pang 2017;41Xu 201738/2018;42Zimenkov 201739 |

| Rv0678 | frameshifts homopolymer nt192–199 | ≥1× | 1× (mixed call: del G198 + del C214), 4× (mixed call: del G19 + E49* + del G198 + ins GA468),3 mixed with other mutations with 7H11 MIC 0.12–0.25 mg/L; 3 isolates with 7H11 MIC 0.24–1.0 mg/L without parent; 2 isolates with 7H11 MIC 0.0074, 0.004 mg/L | 2 clinical isolates confirmed to evolve the mutation at lower allele frequency during infection; 6 clinical isolates with higher MIC; 2 clinical isolates with low MICs | Zimenkov 2017;39Villellas 201744 |

| Rv0678 | mutations nt212–216 | 1–8× | 8× (ins C212); 1× (mixed call: del G198 + del C214), 7H11 0.12 mg/L (mixed call del G198 + del C212 + G78A); 7H9 MIC 0.76 mg/L (R72Q) | 2 clinical resistance evolution; 2 clinical isolates with higher MIC | Andries 2014;33+ Zimenkov 2017;39Xu 201842 |

| Rv0678 | frameshifts nt272–276 | 8× | 8× (IS6110 nt272); 7H11 MIC 0.5–1 mg/L (2 isolates ins A274) | 1 in vitro spontaneous mutant; 2 clinical isolates with higher MIC | Andries 2014;33+ Torrea 2015+; Villellas 201744 |

| Rv0678 | S63R or G | 4× | 4×; 7H11 MIC 0.48 mg/L (also carries R50W mutation) | 1 in vitro integrated Rv0678 with S63R; 1 clinical isolate with S63G and R50W | Hartkoorn 2014;32Villellas 201744 |

Low confidence data are underlined.

A superscript ‘+’ indicates that mmpR or pepQ were not consistently sequenced.

2 of 11 isolates were from low confidence studies, as defined in the methods.

The fourth isolate was tested on unspecified medium and reported to have an MIC of 0.5 mg/L and carried a frameshift at codon 47 (Martinez et al., 2018).46

Effect on MIC Some isolates with mixed mutation calls did not correlate with a change in MIC (Table 2). In pure frameshift calls at nt138–142 and 212–216, bedaquiline MICs increased at least 8-fold but usually mmpR mutations were associated with modest MIC increases of between 2- and 4-fold to both bedaquiline and clofazimine (Tables 2 and 3).

Table 3.

Mutations associated with resistance to clofazimine (CFZ) in ≥2 isolates reported by ≥2 studies or ≥3 isolates reported by ≥1 studya

| Gene | aa change [nt] | MIC summary (relative to parent for available isolates) | MIC change by mutant/study | Data summary | References (in order of data in column 4 and separated by semicolons)b |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Rv0678 | G193 deletion | 2–4× | 2–4× | 23 mutants isolated in vitro from MTB H37Rv | Zhang 20159 |

| Rv0678 | G193 insertion | 2–4× | 2–4× | 22 mutant H37Rv isolates | Zhang 20159 |

| Rv0678 | R156* [C466T] | ≥1–4× | ≥1–4× | 11 mutant H37Rv isolates | Zhang 20159 |

| Rv0678 | C364 insertion | 2–4× | 2–4× | 5 mutant H37Rv isolates | Zhang 20159 |

| Rv0678 | S68G [A202G] | 2–4× | 2–4× (5 isolates); 4× (1 isolate) | 6 isolates evolved in vitro | Zhang 2015;9 Andries 201433 |

| Rv0678 | S63R [C189A] | 4× | 4× | 5 in vitro selected MTB H37Rv mutants | Hartkoorn 201432 |

| Rv0678 | V1A (M1A) [2T>C] | 2–8× | 8×; 4×; unknown; ≥2× | 3 clinical resistance evolution; 2 isolates evolved in vitro | Bloemberg 2015;35+ Hoffman 2016;36+ Somoskovi 2015;47 Zhang 20159 |

| Rv0678 | S53L or P | 4× | 4×; MIC 2–4 mg/L (2 isolates S53P, 1 isolate S53L, unknown parent, MIC breakpoint for CFZ resistance 1.0 mg/L); 2.09 mg/L (no parent) | 1 in vitro selected MTB H37Rv mutant; 4 clinical MTB strains | Zhang 2015;9Pang 2017;41Xu 201738/201842 |

| Rv1979c | V351A [T1052C] | 4× | 4× (2 with Rv0678 ins at nt193) | 3 mutant H37Rv isolates | Zhang 20159 |

Low confidence data underlined.

A superscript ‘+’ indicates that mmpR or pepQ were not consistently sequenced.

pepQ Almeida et al.40 implicated mutations in pepQ, a 273 aa putative Xaa-Pro aminopeptidase in resistance to both bedaquiline and clofazimine by an as-yet-unknown mechanism hypothesized to occur through efflux. Efflux pump inhibitors were reported to revert bedaquiline and clofazimine susceptibility of a pepQ mutant to that of its WT parent.40

Mutational spectrum and effect on MIC Three loss-of-function mutations (L44P and two frameshifts at codons 14 and 271) that evolved in vitro were accompanied by a modest 4-fold increase of bedaquiline and clofazimine MIC.40

Mutations associated with bedaquiline resistance

AtpE This gene encodes the bedaquiline target, the 81 aa ATP synthase subunit C.

Mutational spectrum Fourteen atpE mutations were reported in seven articles, with variants concentrated between codon positions 53 and 72 (Table 2 and Table S1).11,29–31,33,37,39,43,46 The majority of atpE mutations were reported in in vitro isolates. However, atpE D28N, E61E, A63V and I66V were reported in one clinical bedaquiline-resistant isolate each.39,46

Effect on MIC MIC changes due to atpE mutations were higher than the aforementioned mmpR mutations and ranged from 8-fold up to 133-fold increases (Table 2 and Table S1).

Mutations associated with clofazimine resistance

Rv1979c Two studies reported mutations in Rv1979c, encoding a 481 aa probable amino acid membrane transporter with permease activity, in association with clofazimine resistance.9

Mutational spectrum Two mutations were described by Zhang et al.9 (V351A in vitro) and by Xu et al.38 (V52G clinical isolate) (Table 3 and Table S2).

Effect on MIC MIC changes were modest, with increases lower than 4-fold (Table 3).9,38,42

Mutations among bedaquiline- and clofazimine-susceptible and control isolates

Seventeen mmpR mutation patterns were identified in bedaquiline-susceptible isolates (Tables S3 and S4).33,39,42,44,46 These included the C>A substitution 11 bp upstream of mmpR in 40 clinical isolates with low bedaquiline MICs.34,44,46 Moreover, the frameshift indel G in the homopolymer region nt192–198 was reported in two susceptible clinical isolates (Table S4).44 We identified this mutation in 52 of 1373 control MTB isolates (Table S3) that belonged to one sublineage with 51/52 isolates also harbouring a frameshift in nt605 in mmpL5. Twenty-seven mutations in Rv1979 were identified in the control isolate database, with four predicted to have a large impact on the protein (three frameshift and one nonsense); two of the frameshifts were found in isolates with clofazimine 7H10 MIC ≤0.5 mg/L (Table S3).

Isolates that developed bedaquiline or clofazimine resistance without identified mutations

Some studies reported the proportion of isolates or in vitro-evolved strains with bedaquiline or clofazimine phenotypic resistance and no identifiable mutations in the known resistance genes. Zimenkov et al.39 identified 2 of 24 clinical MTB isolates with a 2-fold increase in bedaquiline MIC post-treatment with no recognized mutation in mmpR or atpE, pepQ or Rv1979c genes. Pang et al.41 identified one of five isolates evolving an in-host 2-fold increase in bedaquiline and clofazimine MIC with no identified mutation in atpE, mmpR or pepQ.

Linezolid

We identified 14 studies examining 17 different linezolid resistance mutations in rrl and/or rplC (Table 4).35,39,41,47,49–59

Table 4.

Mutations associated with resistance to linezolid in ≥2 isolates reported by ≥2 studies or ≥3 isolates reported by ≥1 studya

| Gene | aa change [nt] and numbering system (H37Rv unless specified) | MIC summary | MIC change by mutant/study | Data summary | References (in order of data in column 4 and separated by semicolons) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| rplC | C154R [T460C] | 4–32× | 4–16× (4 isolates), ≥1× (3 isolates), MIC not stated (2 isolates); MIC 16.0–32.0 mg/L (3 isolates, 1 double mutation, no parent); >8× (15 isolates); MIC ≥1 mg/L (clinical isolates, no pretreatment data available for 6 of 9 isolates, 3 isolates with mixed mutations); 4× (2 isolates); MIC 4–16 mg/L (2 isolates, no parent); 17× (12 isolates); MIC 4.0 mg/L (clinical isolate, no parent); 8× (2 isolates); 16–32× (7 isolates) | 37 in vitro spontaneous mutants, 22 clinical isolates (2 isolates with heteroresistance, 2 isolates with double mutations), 8 isolates with mutations via plasmid complementation | Beckert 2012;51Zhang 2014;49 Zhang 2016;52Zimenkov 2017;39 Makafe 2016;53Pang 2017;41 McNeil 2017;54Perdigao 2016;55 Lee 2012;58 Balasubramanian 201459 |

| rrl | [G2299T] in H37Rv numbering ([G2061T] in E. coli numbering) | 22–53× | 32× (4 isolates); MIC 32 mg/L (2 clinical isolates, no parent strain); 22–53× | 8 in vitro spontaneous mutants, 2 clinical isolates (1 double mutation) | Hillemann 2008,50Zhang 2014,49 McNeil 201754 |

| rrl | [G2814T] in H37Rv numbering ([G2576T] in E. coli numbering) | 4–32× | 16× (1 isolate); 4–16× (2 isolates, double mutations); MIC ≥1 mg/L (clinical isolate, no pretreatment data available); 8–17× (4 isolates, MIC in solid medium), 32× (1 isolate, MIC90 in liquid medium); MIC ≤1.0 mg/L (clinical isolate, no parent, phenotypically susceptible); 8× (1 isolate) | 6 in vitro selected isolates, 5 clinical isolates (2 isolates with double mutations) | Hillemann 2008,50Somoskovi 201547and Bloemberg 2015,35Zimenkov 2017,39 McNeil 2017,54Banu 2017,56 Lee 201258 |

| rrl | [G2270T], [G2270C] | 8× | 8× (6 isolates); 8× | 7 in vitro spontaneous mutants (8 strains with mutation, 1 without MIC testing) | Zhang 2016,52 Balasubramnian 201459 |

| rrl | [G2746A] | 8× | 8× (5 isolates) | 5 in vitro spontaneous mutants (8 strains with mutation generated, but only 5 with MIC testing) | Zhang 201652 |

Low confidence data underlined.

Mutations associated with resistance to linezolid

rplC Ten studies reported three mutations in rplC, which encodes the 217 aa L3 ribosomal protein.

Mutational spectrum and effect on MIC Mutations were concentrated between Escherichia coli codon positions 460 and 463.39,41,49,51–55,58,59RplC T460C was reported by all 10 studies among a total of 37 in vitro spontaneous mutants and 22 clinical isolates (Table 4). The corresponding effect on the MICs was generally high and ranged from 4- to 32-fold increases (Table 4 and Table S5).

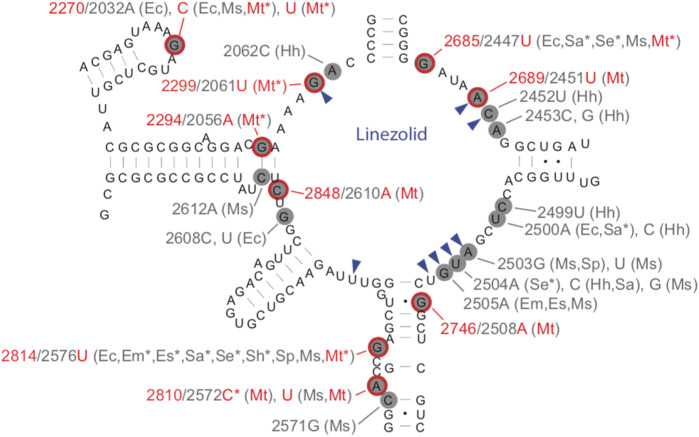

rrl Ten studies examined 14 mutations in rrl, which encodes the 3138 bp 23S rRNA.

Mutational spectrum Mutations reported were widely distributed along the gene (Figure 3, Table S5).35,39,47,49,50,52,54,56–59 The most common mutations occurred at four sites (rrl G2299T, G2814T, G2270T/C and G2746A) (Table 4).35,39,47,49–56,58,59

Figure 3.

Secondary structure of the peptidyltransferase loop of domain V of 23S rRNA. Likely MTB linezolid resistance mutations are circled in red (nucleotide positions for these mutations are also highlighted in red).27,35,39,47,49,52,54,56–59 The most common mutations occurred at four sites based on our systematic review (rrl G2299T, G2814T, G2270T/C and G2746A). Asterisks indicate mutations found in clinical isolates. Nucleotides forming the linezolid-binding pocket are indicated by blue arrowheads. Nucleotide changes correlating with linezolid MIC increases for various organisms are indicated in grey using the E. coli numbering system. Two-letter abbreviations are used for corresponding organisms (Ec, E. coli; Em, Enterococcus faecium; Es, Enterococcus faecalis; Hh, Halobacterium halobium; Sa, Staphylococcus aureus; Se, Staphylococcus epidermidis; Sh, Staphylococcus haemolyticus; Sp, Streptococcus pneumoniae; Ms, Mycobacterium smegmatis; and Mt, MTB). This figure appears in colour in the online version of JAC and in black and white in the print version of JAC.

Effect on MIC Overall rrl mutations were associated with large increases in linezolid MIC ranging between 8- and 50-fold. Rrl G2814T was associated with slightly lower MICs at 4–16-fold in clinical isolates and was identified in one clinical isolate with linezolid MGIT MIC ≤ 1 mg/L.56

Mutations among linezolid-susceptible and control isolates

Seven rrl and rplC mutations not identified in the review were found in the control isolate database (Table S3). The majority of mutations occurred in isolates confirmed to be phenotypically linezolid susceptible.

Isolates that developed resistance without identified mutations

Across eight clinical and in vitro studies with sequencing results for both rrl and rplC, 21/106 linezolid-resistant isolates harboured no mutations.39,41,47,49,52,54,57–59 The majority of these (n = 12) were clinical phenotypically linezolid-resistant strains (MIC levels 2–32 mg/L, breakpoint 1 mg/L) identified by Zhang et al.52 that did not harbour any mutations in rrl or rplC.

Delamanid and pretomanid

Delamanid and pretomanid are prodrugs that require metabolic activation by a deazaflavin (cofactor F420)-dependent nitroreductase Ddn (Rv3547).60 Co-factor F420 is synthesized and reactivated by a group of enzymes encoded by the genes fgd1, fbiA, fbiB and fbiC.15

Five studies reported 12 different mutations in the genes fbiA, fbiC, ddn and fgd1 for delamanid (Table S6).15,35,36,41,61 For pretomanid, four other studies reported 106 different mutations in the same genes (as well as in fbiB) (Table S7).60,62–65 None of the studies measured resistance phenotypes to both drugs.

Mutations associated with resistance to delamanid

fbiA This gene encodes a 331 aa enzyme that biosynthesizes F420.

Mutational spectrum Three fbiA mutations were reported by three studies at codons 49 and 250. (Table S6).15,35,36

Effect on MIC The three mutations in fbiA (D49Y, D49T and K250*) were associated with delamanid resistance and MIC increases were high at 12–32-fold.

fbiC This gene encodes an 856 aa enzyme that participates in F420 biosynthesis. Pang et al.41 identified the fbiC V318I mutation in two clinical isolates with elevated MICs of 32 mg/L. Although no information on the parent isolate was available to deduce association or causation, the two isolates lacked mutations in fbiAB, fgd1 and ddn.

ddn This gene encodes a 151 aa F420-dependent nitroreductase that activates delamanid and pretomanid.

Mutational spectrum Six ddn mutations were reported by two studies spanning codons 20–107.15,61 The most common was W88*, reported among three MDR clinical isolates (Table 5).

Table 5.

Mutations associated with resistance to delamanid in ≥2 isolates reported by ≥2 studies or ≥3 isolates reported by ≥1 studya

| Gene | Mutation | MIC summary | MIC change by mutant/study | Data summary | References (in order of data in column 4 and separated by semicolons) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ddn | W88* | ≥32 mg/L for REMA and ≥16 mg/L for MGIT | REMA MIC ≥32 mg/L, MGIT MIC ≥16 mg/L (3 clinical isolates, no parent, REMA ECOFF 0.03 mg/L and 0.06 mg/L for MGIT) | 3 clinical isolates | Schena 2016 15 |

| ddn | L107P | ≥1 mg/L | REMA MIC ≥32 mg/L and MGIT MIC ≥16 mg/L (1 clinical isolate, no parent, MGIT ECOFF 0.03 mg/L for REMA and 0.06 mg/L for MGIT); 7H11 MIC 1 mg/L (no parent) | 2 clinical isolates | Schena 2016;15Fujiwara 201861 |

REMA, resazurin microtitre assay.

Low confidence data are underlined.

Effect on MIC MIC effect was high at >200 times the ECOFF (Table 5 and Table S6).

fgd1 This gene encodes a 336 aa enzyme that participates in F420 recycling.

Mutational spectrum Two fgd1 mutations were reported by two studies: an fgd1 frameshift at codon 49 and a substitution at codon 320.35,61 Both co-occurred with mutations in other target genes (fbiA D49T and ddn deletion at nt59–101 respectively) and therefore their effect on MIC could not be determined.

Mutations in delamanid-susceptible and control isolates

Twenty-one mutations were found in delamanid-susceptible isolates (Table S4). Six of these were also found in our database of control isolates not previously exposed to nitroimidazoles and were all phylogenetically restricted, suggesting they are likely neutral polymorphisms (Table S3).

Mutations associated with resistance to pretomanid

fgd1 Mutational spectrum Five studies reported 12 fdg1 mutations distributed between codons 43 and 230.60,62–65 Mutations were observed only in in vitro-selected mutants and nearly all in one strain each, except for P43R, which arose twice.

Effect on MIC The effect on MIC was large (>13-fold) for isolates with available MIC data (Table S7).

ddn Mutational spectrum Twenty-three mutation patterns were reported in five studies that examined in vitro-selected resistant isolates spanning codons 8–207.60,62–65 The most common mutations were described by Haver et al.:60 S11* (15 isolates) and Y133D (3 isolates).

Effect on MIC MIC effect was large (generally >27-fold) for isolates with MIC data.

fbiA Mutational spectrum Twenty-seven non-synonymous or frameshift mutations were described by Haver et al.60 to spontaneously arise under pretomanid selection in vitro at codon positions 21–323. Six mutations were seen in two isolates and the remaining variants were only observed in one isolate (Table S7).

Effect on MIC Effect on MIC was large (generally >27-fold) for isolates with MIC data.60

fbiB Mutational spectrum Haver et al.60 reported four mutations at positions 12, 39, 153 and 361 of fbiB. No MICs were measured, but mutant selection was performed on similar concentrations to fbiA and fbiC mutations, for which MIC fold changes were reported to be large.

fbiC Mutational spectrum Forty mutation patterns were reported by four studies to arise with phenotypic resistance in in vitro isolates.60,62,64,65 Two different non-synonymous mutations at codon 720 (V720I and V720G) were identified in six isolates by Haver et al.60

Effect on MIC MIC effect was large (>27-fold) (Table 6).

Table 6.

Mutations associated with resistance to pretomanid in ≥2 isolates reported by ≥2 studies or ≥3 isolates reported by ≥1 study

| Gene | aa change [nt] | MIC summary (relative to parent for available isolates) | MIC change by mutant/study | Data summary | References |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| fbiC | V720I [G2158A] | ≥1–10× | ≥10× (1 isolate), ≥1× (0.36 mg/L selection concentration, 3 isolates, parent MIC ≤0.36 mg/L) ≥5× (1.8 mg/L selection concentration, 1 isolate, parent MIC ≤0.36 mg/L) | 5 in vitro selected mutants, MIC testing done for only 1 isolate | Haver 201560 |

| fbiC | P372S [C1114T] | ≥5× | ≥5× (1.8 mg/L selection concentration, 3 isolates parent MIC ≤0.36 mg/L) | 3 in vitro selected mutants, MIC testing not performed | Haver 201560 |

| fbiC | frameshift [ins C2549] | ≥5× | ≥5× (1.8 mg/L selection concentration, 4 isolates, parent MIC ≤0.36 mg/L) | 4 in vitro selected mutants, MIC testing not performed | Haver 201560 |

| ddn | S11* | ≥10× | ≥10× (15 isolates) | 15 in vitro selected mutants | Haver 201560 |

| ddn | Y133D | ≥5× | ≥5× (1.8 mg/L selection concentration, 3 isolates) | 3 in vitro selected mutants, MIC testing not performed | Haver 201560 |

Mutations in pretomanid-susceptible and control isolates

Five mutations were reported in pretomanid-susceptible isolates (Table S4), two of which were found to be phylogenetically restricted in the control isolate database (Table S3).

Isolates that developed resistance without identified mutations

Pang et al. reported 2/4 XDR clinical isolates resistant to delamanid that harboured no mutations in ddn, fgd1 or fbiABC.41 Haver et al.60 identified 32/183 in vitro-selected pretomanid resistant isolates with no mutations in ddn, fgd1or fbiABC. Two of the 32 had MIC increases of 10-fold or greater.

Discussion

In this systematic review of the literature, we summarize evidence on 277 mutations in 11 genes and drug resistance to five novel and repurposed TB drugs. Given the paucity of data on allelic exchange in MTB, we included studies reporting spontaneous evolution of mutations in the host or in culture and/or studies surveilling clinical isolates with or without drug exposure. We carefully graded the level of confidence for understanding causation between mutation and resistance. We provide a detailed set of mutation–phenotype catalogues that can be used by researchers and clinicians to interpret sequencing data. To our knowledge, this is the most exhaustive catalogue on the topic to date. We extend a recent review that examined 28 papers evaluating genetic variants associated with resistance to the drugs bedaquiline, clofazimine and linezolid and the recent report by WHO that reviewed the evidence for the breakpoints for these agents, by using expanded criteria, a larger number of research databases and including the drugs delamanid and pretomanid.27,66 We also analysed a large control isolate database to verify associations from the literature.

As expected, the spectrum of resistance mutations in essential genes (i.e. atpE, rplC and rrl) was limited.67 It should, therefore, be possible to adapt existing rapid genotypic drug susceptibility testing (DST) technologies (e.g. line probe assays) to interrogate these mutations. By contrast, this is not an option for the remaining non-essential resistance genes. For example, we found more than 100 mutations across the five genes for pretomanid alone, which span a total of 6381 bp. Yet, even if WGS is used to interrogate these genes, interpreting novel mutations will remain a challenge, unless the changes in question can be predicted to result in a loss-of-function phenotype (e.g. in the case of frameshifts).27

We found full clofazimine and bedaquiline cross-resistance for mutations in mmpR and pepQ. Interestingly, we identify several homopolymer or low complexity regions in mmpR that are frameshift hotspots. Specifically, the homopolymer region nt192–198 was by far the most commonly mutated region. However, even frameshifts in mmpR were not consistently associated with clofazimine or bedaquiline resistance. We found naturally occurring indels in nt192–198 in our control database that co-occurred consistently with frameshifts in its regulon gene mmpL5, which encodes an efflux pump. This likely explains why isolates can harbour mmpR frameshifts without measurable increases in MIC and complicates the interpretation of genotypic data even further.44 We therefore suggest that, in addition to sequencing atpE, mmpR and pepQ, the mmpL5-mmpS5 operon should be interrogated to improve the prediction of bedaquiline and clofazimine resistance from genetic data. Although atpE mutations are associated with high-level bedaquiline resistance, both in vitro and in clinical isolates, we found no data on the effect of atpE mutations on clofazimine MICs. One interim report, however, reports four atpE mutant strains that were found to be clofazimine susceptible.27,68 The Rv1979 V52G mutation was reported in a bedaquiline-susceptible but clofazimine-resistant isolate. Our finding that loss-of-function mutations in Rv1979 in the control isolates resulted in isolates phenotypically susceptible to clofazimine raises doubts about the role of Rv1979c in clofazimine resistance.

Cross-resistance between delamanid and pretomanid was difficult to assess as no isolates had MICs measured for both drugs. The most common mutations observed within fbiABC, fgd1 and ddn differed for both drugs, although the diversity of variation in these genes was large and few variants were observed in more than one isolate or repeatedly by different studies. There was a lack of high-confidence data for delamanid and a complete lack of resistance data from clinical isolates for pretomanid. Further research exploring resistance mechanisms to the nitroimidazoles should be prioritized, especially as these drugs are part of the promising all-oral regimens for MDR-TB.69,70

Linezolid is increasingly repurposed for the treatment of both MDR- and XDR-TB due to promising clinical data.58,71 Prior studies of MDR isolates have reported emerging linezolid resistance, with rates ranging between 1.9% and 10.8%.52,58,71 We found several rplC and rrl mutations associated with linezolid resistance but, notably, a sizable proportion of linezolid-resistant isolates were found to have no mutations in rrl or rplC (n = 21/106, 20%). This could be due to low-frequency resistance mutations that were missed, mutations in novel resistance genes or, alternatively, erroneous phenotypic DST results. In light of the side effects of linezolid, appropriately designed experiments are called for to distinguish the relative contributions of these possible explanations.72

This systematic review was not without limitations. A major challenge was the diversity of phenotypic testing methods, especially as phenotypic testing for the novel drugs is still not well standardized and the evidence for the breakpoints is limited.27,73 For this reason, we highlighted studies that relied solely on the comparison of absolute MIC values as ‘lower confidence’ and studies that assessed fold change in MIC relative to the susceptible parent isolate as ‘higher confidence’. For several drugs and mutations, MIC increases were modest, which means that the reproducibility of phenotypic DST for both drugs is likely poor due to the inherent technical variation in testing.4

In summary, this exhaustive systematic review highlights the current understanding of causal and associative relationships between genetic mutations and phenotypic resistance to five novel and repurposed TB drugs. Access to several of the novel TB drugs remains limited and phenotypic testing is only available in a few mycobacteriology laboratories around the globe.34 At the same time, MTB WGS data is being generated at an increasing pace for transmission inference and first-line resistance diagnosis.5,6 Here we provide a knowledge base to aid the repurposing of WGS data for detection/surveillance of resistance to the novel drugs that will also support research explorations of resistance mechanisms and new molecular diagnostic development, the ultimate goal being more personalized antibiotic therapy for patients with resistant TB.

Funding

This work was funded by an NIH/BD2K award K01 ES026835 to M.F.

Transparency declarations

C.U.K. is a consultant for the WHO Regional Office for Europe, Becton Dickinson, and QuantuMDx Group Ltd. C.U.K. is an unpaid advisor to GenoScreen and consulted for the Foundation for Innovative New Diagnostics, which involved work for Cepheid Inc., Hain Lifescience, and WHO. The Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation and Hain Lifescience covered C.U.K.’s travel and accommodation to present at meetings. The Global Alliance for TB Drug Development Inc. and Otsuka Novel Products GmbH have supplied C.U.K. with antibiotics for in vitro research. YD Diagnostics has provided C.U.K. with assays for an evaluation. All other authors have none to declare.

Supplementary data

Figures S1 to S4 and Tables S1 to S7 are available as Supplementary data at JAC Online.

Supplementary Material

References

- 1.WHO. Global Tuberculosis Report 2019. https://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/handle/10665/329368/9789241565714-eng.pdf? ua=1.

- 2. Diacon AH, Pym A, Grobusch M. et al. The diarylquinoline TMC207 for multidrug-resistant tuberculosis. N Engl J Med 2009; 360: 2397–405. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Gler MT, Skripconoka V, Sanchez-Garavito E. et al. Delamanid for multidrug-resistant pulmonary tuberculosis. N Engl J Med 2012; 366: 2151–60. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Köser CU, Maurer FP, Kranzer K.. “Those who cannot remember the past are condemned to repeat it”: drug-susceptibility testing for bedaquiline and delamanid. Int J Infect Dis 2019; 80S: S32–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.The CRyPTIC Consortium and the 100000 Genomes Project, Allix-Beguec C, Arandjelovic I. et al. Prediction of susceptibility to first-line tuberculosis drugs by DNA sequencing. N Engl J Med 2018; 379: 1403–15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Farhat MR, Sultana R, Iartchouk O. et al. Genetic determinants of drug resistance in Mycobacterium tuberculosis and their diagnostic value. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2016; 194: 621–30. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Lamprecht DA, Finin PM, Rahman MA. et al. Turning the respiratory flexibility of Mycobacterium tuberculosis against itself. Nat Commun 2016; 7: 12393. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Browne SG, Hogerzeil LM.. ‘B 663’ in the treatment of leprosy. Preliminary report of a pilot trial. Lepr Rev 1962; 33: 6–10. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Zhang S, Chen J, Cui P. et al. Identification of novel mutations associated with clofazimine resistance in Mycobacterium tuberculosis. J Antimicrob Chemother 2015; 70: 2507–10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Yano T, Kassovska-Bratinova S, Teh JS. et al. Reduction of clofazimine by mycobacterial type 2 NADH:quinone oxidoreductase: a pathway for the generation of bactericidal levels of reactive oxygen species. J Biol Chem 2011; 286: 10276–87. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Andries K, Verhasselt P, Guillemont J. et al. A diarylquinoline drug active on the ATP synthase of Mycobacterium tuberculosis. Science 2005; 307: 223–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Srivastava S, Magombedze G, Koeuth T. et al. Linezolid dose that maximizes sterilizing effect while minimizing toxicity and resistance emergence for tuberculosis. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 2017; 61: e00751–17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Keam SJ. Pretomanid: first approval. Drugs 2019; 79: 1797–803. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Köser CU, Javid B, Liddell K. et al. Drug-resistance mechanisms and tuberculosis drugs. Lancet 2015; 385: 305–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Schena E, Nedialkova L, Borroni E. et al. Delamanid susceptibility testing of Mycobacterium tuberculosis using the resazurin microtitre assay and the BACTECTM MGITTM 960 system. J Antimicrob Chemother 2016; 71: 1532–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Gurumurthy M, Mukherjee T, Dowd CS. et al. Substrate specificity of the deazaflavin-dependent nitroreductase from Mycobacterium tuberculosis responsible for the bioreductive activation of bicyclic nitroimidazoles. FEBS J 2012; 279: 113–25. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Nebenzahl-Guimaraes H, Jacobson KR, Farhat MR. et al. Systematic review of allelic exchange experiments aimed at identifying mutations that confer drug resistance in Mycobacterium tuberculosis. J Antimicrob Chemother 2014; 69: 331–42. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Bottger EC. The ins and outs of Mycobacterium tuberculosis drug susceptibility testing. Clin Microbiol Infect 2011; 17: 1128–34. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Farhat MR, Freschi L, Calderon R. et al. GWAS for quantitative resistance phenotypes in Mycobacterium tuberculosis reveals resistance genes and regulatory regions. Nat Commun 2019; 10: 2128. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Schmieder R, Edwards R.. Quality control and preprocessing of metagenomic datasets. Bioinformatics 2011; 27: 863–4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Ezewudo M, Borens A, Chiner-Oms Á. et al. Integrating standardized whole genome sequence analysis with a global Mycobacterium tuberculosis antibiotic resistance knowledgebase. Sci Rep 2018; 8: 15382. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Wood DE, Salzberg SL.. Kraken: ultrafast metagenomic sequence classification using exact alignments. Genome Biol 2014; 15: R46. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Li H. Aligning sequence reads, clone sequences and assembly contigs with BWA-MEM. http://arxiv.org/abs/1303.3997.

- 24.Broad Institute. Picard toolkit. 2019. http://broadinstitute.github.io/picard/.

- 25. Walker BJ, Abeel T, Shea T. et al. Pilon: an integrated tool for comprehensive microbial variant detection and genome assembly improvement. PLoS One 2014; 9: e112963. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Coll F, McNerney R, Guerra-Assunção JA. et al. A robust SNP barcode for typing Mycobacterium tuberculosis complex strains. Nat Commun 2014; 5: 4812. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.WHO. Technical Report on critical concentrations for TB drug susceptibility testing of medicines used in the treatment of drug-resistant TB. 2018. https://www.who.int/tb/publications/2018/WHO_technical_report_concentrations_TB_drug_susceptibility/en/.

- 28. van Klingeren B, Dessens-Kroon M, van der Laan T. et al. Drug susceptibility testing of Mycobacterium tuberculosis complex by use of a high-throughput, reproducible, absolute concentration method. J Clin Microbiol 2007; 45: 2662–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Petrella S, Cambau E, Chauffour A. et al. Genetic basis for natural and acquired resistance to the diarylquinoline R207910 in mycobacteria. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 2006; 50: 2853–6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Huitric E, Verhasselt P, Koul A. et al. Rates and mechanisms of resistance development in Mycobacterium tuberculosis to a novel diarylquinoline ATP synthase inhibitor. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 2010; 54: 1022–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Segala E, Sougakoff W, Nevejans-Chauffour A. et al. New mutations in the mycobacterial ATP synthase: new insights into the binding of the diarylquinoline TMC207 to the ATP synthase C-ring structure. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 2012; 56: 2326–34. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Hartkoorn RC, Uplekar S, Cole ST.. Cross-resistance between clofazimine and bedaquiline through upregulation of MmpL5 in Mycobacterium tuberculosis. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 2014; 58: 2979–81. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Andries K, Villellas C, Coeck N. et al. Acquired resistance of Mycobacterium tuberculosis to bedaquiline. PLoS One 2014; 9: e102135. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Torrea G, Coeck N, Desmaretz C. et al. Bedaquiline susceptibility testing of Mycobacterium tuberculosis in an automated liquid culture system. J Antimicrob Chemother 2015; 70: 2300–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Bloemberg GV, Keller PM, Stucki D. et al. Acquired resistance to bedaquiline and delamanid in therapy for tuberculosis. N Engl J Med 2015; 373: 1986–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Hoffmann H, Kohl TA, Hofmann-Thiel S. et al. Delamanid and bedaquiline resistance in Mycobacterium tuberculosis ancestral Beijing genotype causing extensively drug-resistant tuberculosis in a Tibetan refugee. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2016; 193: 337–40. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Tantry SJ, Shinde V, Balakrishnan G. et al. Scaffold morphing leading to evolution of 2,4-diaminoquinolines and aminopyrazolopyrimidines as inhibitors of the ATP synthesis pathway. MedChemComm 2016; 7: 1022–32. [Google Scholar]

- 38. Xu J, Wang B, Hu M. et al. Primary clofazimine and bedaquiline resistance among isolates from patients with multidrug-resistant tuberculosis. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 2017; 61: e00239–17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Zimenkov DV, Nosova EY, Kulagina EV. et al. Examination of bedaquiline- and linezolid-resistant Mycobacterium tuberculosis isolates from the Moscow region. J Antimicrob Chemother 2017; 72: 1901–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Almeida D, Ioerger T, Tyagi S. et al. Mutations in pepQ confer low-level resistance to bedaquiline and clofazimine in Mycobacterium tuberculosis. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 2016; 60: 4590–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Pang Y, Zong Z, Huo F. et al. In vitro drug susceptibility of bedaquiline, delamanid, linezolid, clofazimine, moxifloxacin, and gatifloxacin against extensively drug-resistant tuberculosis in Beijing, China. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 2017; 61: e00900–17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Xu J, Tasneen R, Peloquin CA. et al. Verapamil increases the bioavailability and efficacy of bedaquiline but not clofazimine in a murine model of tuberculosis. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 2018; 62: e01692–17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Tantry SJ, Markad SD, Shinde V. et al. Discovery of imidazo[1,2-a]pyridine ethers and squaramides as selective and potent inhibitors of mycobacterial adenosine triphosphate (ATP) synthesis. J Med Chem 2017; 60: 1379–99. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Villellas C, Coeck N, Meehan CJ. et al. Unexpected high prevalence of resistance-associated Rv0678 variants in MDR-TB patients without documented prior use of clofazimine or bedaquiline. J Antimicrob Chemother 2017; 72: 684–90. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Veziris N, Bernard C, Guglielmetti L. et al. Rapid emergence of Mycobacterium tuberculosis bedaquiline resistance: lessons to avoid repeating past errors. Eur Respir J 2017; 49: 1601719. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Martinez E, Hennessy D, Jelfs P. et al. Mutations associated with in vitro resistance to bedaquiline in Mycobacterium tuberculosis isolates in Australia. Tuberculosis (Edinb) 2018; 111: 31–4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Somoskovi A, Bruderer V, Hömke R. et al. A mutation associated with clofazimine and bedaquiline cross-resistance in MDR-TB following bedaquiline treatment. Eur Respir J 2015; 45: 554–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Aung HL, Nyunt WW, Fong Y. et al. First 2 extensively drug-resistant tuberculosis cases from Myanmar treated with bedaquiline. Clin Infect Dis 2017; 65: 531–2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Zhang Z, Pang Y, Wang Y. et al. Beijing genotype of Mycobacterium tuberculosis is significantly associated with linezolid resistance in multidrug-resistant and extensively drug-resistant tuberculosis in China. Int J Antimicrob Agents 2014; 43: 231–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Hillemann D, Rüsch-Gerdes S, Richter E.. In vitro-selected linezolid-resistant Mycobacterium tuberculosis mutants. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 2008; 52: 800–1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Beckert P, Hillemann D, Kohl TA. et al. rplC T460C identified as a dominant mutation in linezolid-resistant Mycobacterium tuberculosis strains. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 2012; 56: 2743–5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Zhang S, Chen J, Cui P. et al. Mycobacterium tuberculosis mutations associated with reduced susceptibility to linezolid. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 2016; 60: 2542–4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Makafe GG, Cao Y, Tan Y. et al. Role of the Cys154Arg substitution in ribosomal protein L3 in oxazolidinone resistance in Mycobacterium tuberculosis. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 2016; 60: 3202–6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. McNeil MB, Dennison DD, Shelton CD. et al. In vitro isolation and characterization of oxazolidinone-resistant Mycobacterium tuberculosis. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 2017; 61: e01296–17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Perdigão J, Maltez F, Machado D. et al. Beyond extensively drug-resistant tuberculosis in Lisbon, Portugal: a case of linezolid resistance acquisition presenting as an iliopsoas abscess. Int J Antimicrob Agents 2016; 48: 569–70. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56. Banu S, Pholwat S, Foongladda S. et al. Performance of TaqMan array card to detect TB drug resistance on direct specimens. PLoS One 2017; 12: e0177167. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57. Heyckendorf J, Andres S, Köser CU. et al. What is resistance? Impact of phenotypic versus molecular drug resistance testing on therapy for multi- and extensively drug-resistant tuberculosis. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 2018; 62: e01550–17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58. Lee M, Lee J, Carroll MW. et al. Linezolid for treatment of chronic extensively drug-resistant tuberculosis. N Engl J Med 2012; 367: 1508–18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59. Balasubramanian V, Solapure S, Iyer H. et al. Bactericidal activity and mechanism of action of AZD5847, a novel oxazolidinone for treatment of tuberculosis. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 2014; 58: 495–502. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60. Haver HL, Chua A, Ghode P. et al. Mutations in genes for the F420 biosynthetic pathway and a nitroreductase enzyme are the primary resistance determinants in spontaneous in vitro-selected PA-824-resistant mutants of Mycobacterium tuberculosis. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 2015; 59: 5316–23. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61. Fujiwara M, Kawasaki M, Hariguchi N. et al. Mechanisms of resistance to delamanid, a drug for Mycobacterium tuberculosis. Tuberculosis (Edinb) 2018; 108: 186–94. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62. Manjunatha UH, Boshoff H, Dowd CS. et al. Identification of a nitroimidazo-oxazine-specific protein involved in PA-824 resistance in Mycobacterium tuberculosis. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 2006; 103: 431–6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63. Feuerriegel S, Köser CU, Baù D. et al. Impact of fgd1 and ddn diversity in Mycobacterium tuberculosis complex on in vitro susceptibility to PA-824. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 2011; 55: 5718–22. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64. Kidwai S, Park C-Y, Mawatwal S. et al. Dual mechanism of action of 5-nitro-1,10-phenanthroline against Mycobacterium tuberculosis. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 2017; 61: e00969–17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65. Hurdle JG, Lee RB, Budha NR. et al. A microbiological assessment of novel nitrofuranylamides as anti-tuberculosis agents. J Antimicrob Chemother 2008; 62: 1037–45. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66. Ismail N, Omar SV, Ismail NA. et al. Collated data of mutation frequencies and associated genetic variants of bedaquiline, clofazimine and linezolid resistance in Mycobacterium tuberculosis. Data Brief 2018; 20: 1975–83. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67. DeJesus MA, Gerrick ER, Xu W. et al. Comprehensive essentiality analysis of the Mycobacterium tuberculosis genome via saturating transposon mutagenesis. mBio 2017; 8: e02133–16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68. Ismail N, Peters RPH, Ismail NA. et al. Clofazimine exposure in vitro selects efflux pump mutants and bedaquiline resistance. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 2019; 63: e02141–18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69. Everitt D, Conradie F. A Phase 3 Study Assessing the Safety and Efficacy of Bedaquiline Plus PA-824 Plus Linezolid in Subjects With Drug Resistant Pulmonary Tuberculosis. https://clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/show/NCT02333799.

- 70. Conradie F, Diacon A, Everitt D. et al. The Nix-TB Trial of Pretomanid, Bedaquiline and Linezolid to Treat XDR-TB. Conference on Retroviruses and Opportunistic Infections, Seattle, Washington, USA, 8–11 March 2020 Abstract 80LB. https://www.croiconference.org/sessions/nix-tb-trial-pretomanid-bedaquiline-and-linezolid-treat-xdr-tb.

- 71. Schecter GF, Scott C, True L. et al. Linezolid in the treatment of multidrug-resistant tuberculosis. Clin Infect Dis 2010; 50: 49–55. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72. Schön T, Miotto P, Köser CU. et al. Mycobacterium tuberculosis drug-resistance testing: challenges, recent developments and perspectives. Clin Microbiol Infect 2017; 23: 154–60. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73. Schön T, Matuschek E, Mohamed S. et al. Standards for MIC testing that apply to the majority of bacterial pathogens should also be enforced for Mycobacterium tuberculosis complex. Clin Microbiol Infect 2019; 25: 403–5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.