Abstract

Background

Dialysis care often focuses on outcomes that are of lesser importance to patients than to clinicians. There is growing international interest in individualizing care based on patient priorities, but evidence-based approaches are lacking. The objective of this study was to develop a person-centered dialysis care planning program. To achieve this objective we performed qualitative interviews, responsively developed a novel care planning program and then assessed program content and burden.

Methods

We conducted 25 concept elicitation interviews with US hemodialysis patients, care partners and care providers, using thematic analysis to analyze transcripts. Interview findings and interdisciplinary stakeholder panel input informed the development of a new care planning program, My Dialysis Plan. We then conducted 19 cognitive debriefing interviews with patients, care partners and care providers to assess the program’s content and face validities, comprehensibility and burden.

Results

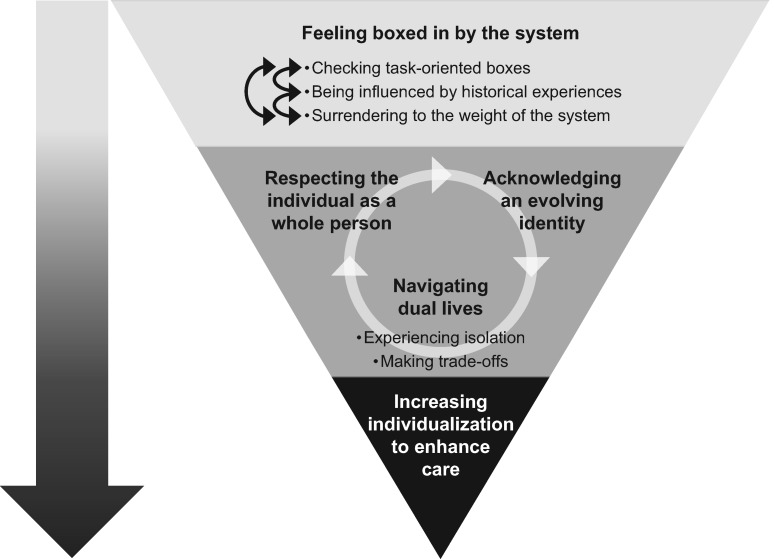

We identified five themes in concept elicitation interviews: feeling boxed in by the system, navigating dual lives, acknowledging an evolving identity, respecting the individual as a whole person and increasing individualization to enhance care. We then developed a person-centered care planning program and supporting materials that underwent 32 stakeholder-informed iterations. Data from subsequent cognitive interviews led to program revisions intended to improve contextualization and understanding, decrease burden and facilitate implementation.

Conclusions

My Dialysis Plan is a content-valid, person-centered dialysis care planning program that aims to promote care individualization. Investigation of the program’s capacity to improve patient experiences and outcomes is needed.

Keywords: care plan, dialysis, person-centered, priorities, qualitative research

INTRODUCTION

Dialysis care often focuses on biochemical markers and other easily quantifiable metrics, yet patients prioritize outcomes relevant to their well-being and lifestyle, such as fatigue, relationships and ability to travel [1, 2]. Patients and providers from diverse international regions have described dialysis care as prescriptive, focused on dialysis ‘process’ rather than dialysis ‘care’ [3–5]. Existing data suggest that the absence of meaningful care team engagement and inadequate individualization of care detract from patients’ experiences [6, 7]. To promote more person-centered care, patient-enriched stakeholder groups [8] and the international guideline body, Kidney Disease: Improving Global Outcomes [9], have advocated aligning dialysis care with patient-identified ‘life goals’.

Person-centered care is an extension of patient-centered care, defined by the Institute of Medicine as care that is ‘respectful of and responsive to individual patient preferences, needs, and values, and ensuring that patient values guide all clinical decisions’. [10]. While patient-centered care focuses on ‘patient’ interactions with the health system, person-centered care shifts the focus to the individual [11–13]. It rests on four principles: delivering care with compassion, respect and dignity; providing well-coordinated care; individualizing care to account for medical, psychosocial and practical needs; and enabling patients to assume active roles in their care [11, 13, 14]. Applying the philosophy of person-centered care to dialysis could promote alignment of dialysis care with patient-identified goals and priorities. Despite the growing interest in this approach [3, 13, 15], there are few evidence-based processes to support implementation. However, the dialysis interdisciplinary plan of care (i.e. care plan) represents an existing process that could be used to identify and address patient goals, although current approaches often fall short [3].

We undertook this study to develop a person-centered dialysis care planning program. To achieve this objective we characterized patient and dialysis care team perspectives on life goals and dialysis care planning, used our findings to inform the development of a novel approach to the interdisciplinary plan of care and performed cognitive debriefing interviews to assess content and face validities, comprehensibility and burden of the program’s supporting materials.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

We followed the Consolidated Criteria for Reporting Qualitative Health Research (Supplementary data, Table S1) [16]. These studies were approved by the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill Institutional Review Boards (studies 18-1735 and 18-3083). All participants provided informed consent.

Concept elicitation interview participants and data collection

For concept elicitation interviews, we recruited adult maintenance hemodialysis patients, care partners (i.e. family members) and care providers (i.e. dialysis clinic personnel and medical providers) from four North Carolina dialysis clinics. We included care partners as patient proxy reporters in efforts to increase the depth of our data, not to replace patient-reported data. We excluded individuals receiving hemodialysis for <3 months or with cognitive impairment (per nephrologist) and non-English speakers. We used purposive sampling to promote diversity in age, dialysis vintage, education level and professional role [17]. Participants received a $30 remuneration.

We developed a semistructured interview guide (Supplementary data, Table S2) based on a literature review and input from a 12-member stakeholder panel (5 individuals living with kidney disease, 5 medical providers and 2 dialysis clinic personnel). Interviews were conducted in a private setting, recorded and transcribed.

Care planning program development

We then developed an interdisciplinary person-centered care planning program that is rooted in the goal-directed care model. Goal-directed care, a conceptual framework for delivering person-centered care, involves framing medical decision-making around patient goals (i.e. priorities) rather than medical problems [18–22]. The approach promotes collaboration between patients and care teams and facilitates individualization of care through mutually agreed upon meaningful goals. Drawing upon our elicited patient and care partner perspectives on goals and dialysis care plans, as well as care provider perspectives on goal-directed care planning implementation, three research team members (A.D., D.F. and J.E.F.) developed a draft program and supporting materials. Iterative stakeholder input informed initial draft edits. We then conducted cognitive debriefing interviews with the target population to identify additional modifications.

Cognitive debriefing interview participants and data collection

Using the same selection criteria, sampling strategy and recruitment methods as for concept elicitation interviews, we recruited hemodialysis patients, care partners and care provider participants from two North Carolina dialysis clinics for cognitive debriefing interviews. To enrich the sample with input from individuals unfamiliar with the project, we recruited additional individuals who did not participate in concept elicitation interviews. Participants received a $25 remuneration.

Cognitive interviews assessed the new care planning materials’ content, face validity, comprehensibility and burden. We also sought to understand the feasibility of program implementation in real-world clinical environments. Participants used the think-aloud method while reviewing and annotating the draft materials [23]. Thereafter, one interviewer (A.D.) performed semistructured interviews to elicit more detailed information (Supplementary data, Table S2). Participant responses were recorded on standardized note templates. Materials were iterated in accordance with interview findings and updated versions were returned to participants for review.

Data analysis

A professional transcription service transcribed digitally recorded concept elicitation interviews. We imported transcriptions into ATLAS.ti software (version 7, Berlin, Germany) and analyzed the data using inductive thematic analysis as described by Clarke and Braun [24, 25]. Two team members (A.D. and S.L.M.) used line-by-line coding to identify concepts within transcripts. We reviewed field notes on nonverbal behaviors, interview settings and reasons for interview guide question adaptations to provide additional context for participant responses [26]. Through iterative discussions (researcher triangulation), researchers (A.D., S.L.M. and J.E.F.) categorized semantically related concepts into themes and subthemes. In doing so, we identified overlap across concepts in patient, care partner and care provider transcripts. Data were thus pooled across participant types. The team returned to source data to corroborate findings and develop a thematic schema. Interviews were ceased when no new codes were identified after three consecutive interviews (data saturation).

Cognitive debriefing data were entered into the Research Electronic Data Capture database. We aggregated the data in table format by materials type and section to identify needed updates. When evaluating comprehension and relevance, we weighted information provided by three or more participants.

RESULTS

Participant characteristics

We completed 25 concept elicitation interviews with 13 hemodialysis patients, 3 care partners and 9 providers (Table 1). The average age of patient participants was 57 ± 9 years, six (46%) were female and eight (62%) had received dialysis for at least 6 years. Among provider participants, four (44%) were medical providers (physicians, advanced practice providers) and five (56%) were clinic personnel (dietitians, social workers, nurses) who together averaged 11 ± 7 years of experience working in dialysis.

Table 1.

Participant characteristics a

| Characteristics | Concept elicitation (n=25) | Cognitive interviews (n=19) |

|---|---|---|

| Dialysis patient interviews, n | 13 | 9 |

| Age (years), median (range) | 54 (46–74) | 62 (36–72) |

| Female, n (%) | 6 (46.1) | 3 (33.3) |

| Race, n (%) | ||

| Black | 12 (92.3) | 6 (66.7) |

| White | 0 (0) | 2 (22.2) |

| Mixed | 1 (7.7) | 1 (11.1) |

| Dialysis vintage (years) | ||

| ≤1 | 1 (7.7) | 2 (22.2) |

| 2–5 | 4 (30.8) | 3 (33.3) |

| ≥6 | 8 (61.5) | 4 (44.4) |

| Education, n (%) | ||

| <High school | 2 (15.4) | 0 (0) |

| High school graduate | 8 (61.5) | 3 (33.3) |

| Some college | 2 (15.4) | 5 (55.5) |

| College graduate or more | 1 (7.7) | 1 (11.1) |

| Positive recall of dialogue about healthcare goals with dialysis care team, n (%) | 8 (61.5) | – |

| Interview duration (min), median (range) | 54 (34–82) | 44 (36–65) |

| Dialysis care partner interviews, n | 3 | 1 |

| Age (years), median (range) | 69 (53–79) | 60 |

| Female, n (%) | 3 (100) | 1 |

| Race, n (%) | ||

| Black | 2 (66.6) | 0 (0) |

| White | 1 (33.3) | 1 (100) |

| Dialysis vintage of patient (years), n (%) | ||

| ≤1 | 1 (33.3) | 0 (0) |

| 2–5 | 1 (33.3) | 0 (0) |

| ≥6 | 1 (33.3) | 1 (100) |

| Interview duration (min), median (range) | 47 (45–61) | 37 |

| Dialysis care provider interviews, n | 9 | 9 |

| Participant type, n (%) | ||

| Medical providerb | 4 (44.4) | 4 (44.4) |

| Dietitian | 2 (22.2) | 0 (0) |

| Social worker | 2 (22.2) | 3 (33.3) |

| Nurse | 1 (11.1) | 2 (22.2) |

| Time in role (years), median (range) | 4 (0.2–19) | 4 (0.2–14) |

| Time in dialysis care (years), median (range) | 11 (3–23) | 13 (2.5–23) |

| Positive interest in incorporating GDC into dialysis care, n (%) | 9 (100) | – |

| Interview duration (min), median (range) | 63 (54–85) | 58 (47–88) |

Thirteen (68%) cognitive debriefing interview participants were unique from concept elicitation interview participants. All characteristics data were self-reported by participants.

Medical provider participant type includes five unique physicians and one advanced practice provider.

GDC: goal-directed care.

We completed 19 cognitive debriefing interviews with 9 hemodialysis patients, 1 care partner and 9 care providers. The average age of patient participants was 60 ± 11 years and three (33%) were female. Among providers, four (44%) were medical providers and five (56%) were clinic personnel who together averaged 12 ± 7 years of experience working in dialysis.

Concept elicitation interview themes

We identified five major themes: feeling boxed in by the system, navigating dual lives, acknowledging an evolving identity, respecting the individual as a whole person and increasing individualization to enhance care. Figure 1 displays the thematic schema. Table 2 and Supplementary data, Table S3 contain illustrative quotations.

FIGURE 1.

Thematic schema from concept elicitation interviews. The thematic schema displays the identified themes and subthemes: (i) feeling boxed in by the system (checking task-oriented boxes, surrendering to the weight of the system and being influenced by historical experiences); (ii) navigating dual lives (experiencing isolation and making trade-offs); (iii) acknowledging an evolving identity; (iv) respecting the individual as a whole person and (v) increasing individualization to enhance care. As indicated by the downward-directed arrow, the upside down triangle depicts how the themes of feeling boxed in by the system, navigating dual lives, acknowledging an evolving identity and respecting the individual as a whole person all point to care individualization as a vehicle by which to enhance care. The circular arrow connecting navigating dual lives, acknowledging an evolving identity and respecting the individual as a whole person reflects the interconnected nature of these three themes.

Table 2.

Illustrative quotations from concept elicitation interview participants

| Themes and subthemes with supporting quotations |

|---|

| Feeling boxed in by the system |

| Checking task-oriented boxes |

| Care Partner: ‘The team meetings are just a walk-through to check off the boxes, because Medicare probably requires it quarterly’. |

| Nurse: ‘…it's just the same routine thing over and over and over and not necessarily getting anywhere. It's more just check the boxes…I don't think [patients] look at it as a way for them to let me know really what's going on’. |

| Medical provider: ‘I think it’s artificial, contrived, ineffective most of the time; more about dotting ‘I's’ than it is actual care planning’. |

| Surrendering to the weight of the system |

| Patient: ‘I don’t ask for nothing, and I just come in, try to do this, get it out of the way and get out of here’. |

| Nurse: ‘It's like we do [individualize care], and then it just kind of dwindles back down to those rigid guidelines because we lose that personal touch. Over time you have so many people, and it's just a rush and it's what we have to get to’. |

| Social worker: ‘I do feel like we often rush through the care plan to get through the requirement. I think we often just lose over time—just kind of with anything—you lose the value of why care plans are important, and your main focus is to get in compliance’. |

| Medical provider: ‘… we have to do things a certain way, you know, and there’s protocols and there’s standards and there’s research and formulas as to why we do it this way…it just sometimes feels like you’re just slapping [the patient] on the hand with a ruler, like back away now… this is ours. And you feel like you’re practicing this very paternalistic form of medicine’. |

| Being influenced by historical experiences |

| Patient: ‘I just keep it to myself, because [the care team is] not really going to put forth an effort to fix none of it, and I don’t like to waste my time’. |

| Care partner: ‘I did not bring my ambitious self to the [recent care plan] meeting because I didn’t feel there was anything that happened after the last [care plan] meeting’. |

| Social worker: ‘… if it’s something [patients] feel like they asked for before and it hasn’t been honored or if patients get fussed at too much. It just depends on…the history of what’s happened with the team and how well-supported [patients] feel’. |

| Navigating dual lives |

| Experiencing isolation |

| Patient: ‘Sometimes it’s hard to explain to family what you’re really going through because they’re not here’. |

| Care partner: ‘He was used to working, and mingling, and having friends in different areas. But he’s not able to do that no more, and I think that that might have something to do with that feeling of [not having] self-worth’. |

| Making trade-offs |

| Patient: ‘It’s not so much dialysis get in the way, it’s the effects of dialysis…Because you never know, sometimes you may plan something but then the next day you’re just not feeling well so you may have to cancel your plans or rearrange things in your schedule’. |

| Social worker: ‘A [patient] said, I just want to try to reduce my treatment time to see if that’ll let me be able to cook more and be with my family more. So we looked at that goal and tried to figure out what we could do, and reduced her time, and now she’s feeling better, but she’s not meeting clinical guidelines. But she’s happier…it’s stressful for the [care] team’. |

| Acknowledging an evolving identity |

| Patient: ‘I don't go like I used to. I just sit at home more, and I don't do nothing, really. Well, I used to be a busy body going all the time, but I just sit at home now’. |

| Nurse: ‘I don't think people really know who they are. They kind of lose that because they're so busy just trying to survive day-to-day with following the diet and getting their treatment and taking their medicine and that sort of thing … so they lose that interest, like knitting or whatever they might want to do’. |

| Respecting the individual as a whole person |

| Patient: ‘[It] was like you just some number, you know, like you—kind of like cattle, and get through your little assessment and then go onto the next person’. |

| Patient: ‘Well, I think it’s two-fold. I think the medical care of dialysis, the treatments are good, and I think the personal is also good. I think it has to be intertwined, you know… to meet the goals of the total person?’ |

| Nurse: ‘…it would be nice for the patient to know that we take interest in them as a person versus a patient’. |

| Medical provider: ‘If I would just look at dialysis care, it’s just going to be looking at those [quantitative] parameters. If I look at the patient as a whole, you start looking at other sort of parameters, as well…I think that would be looking at the patient instead of just looking at dialysis’. |

| Increasing individualization to enhance care |

| Patient: ‘The more [the care team] knows, the more the care plans are individually catered to each patient, because everybody’s different, although the goals may be the same, but it may be different how you attain those goals’. |

| Nurse: ‘I feel that if anybody—anybody, not just the patient, but if you recognize that I'm taking a personal interest in you, you're going to be more willing to open up to me, to talk to me, and maybe come to me whenever you feel like you need help or to share an accomplishment’. |

| Medical provider: ‘I think that we should be incorporating patients’ goals into their care, and I think we need to come up with a way to sort of measure that and make sure that they’re moving forward in it, just like we do phosphorous’. |

Feeling boxed in by the system. Participants lamented that the dialysis delivery system structure often negatively affected care provision and hence patient experiences with care plans. Three subthemes (checking task-oriented boxes, surrendering to the weight of the system and being influenced by historical experiences) comprised this theme. Many care providers described feeling confined by requirements set forth by payers and dialysis organizations. They acknowledged that these expectations positively and negatively influenced care (e.g. creating professional accountability while artificially pushing laboratory goals). Many patients described this system-imposed rigidity as negatively influencing their experiences, leading to feelings of resentment and questions about care team intentions.

Providers experienced the weight of the system through pressure to ‘check-off’ task-oriented responsibilities. A dietitian commented, ‘It feels like we’re doing the care plan just to meet criteria or requirements for Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS)’. In turn, patients experienced comparable weight when they perceived these system-dictated responsibilities as taking priority over patient-identified needs. These feelings were unwanted by providers and patients alike, yet omnipresent; all felt powerless to impose change due to workload, limited understanding or prior unsuccessful attempts. As such, they ultimately surrendered to the system. Past negative experiences with care planning and overall dialysis care influenced both the providers’ and patients’ ability to imagine change.

Navigating dual lives. Participants described challenges arising from oscillating between dual worlds (dialysis and nondialysis), each with its own and often conflicting pressures. Two subthemes (experiencing isolation and making trade-offs) comprised this theme. For some patients, their dialysis and nondialysis lives intersected, but for others, the two remained independent. Many providers acknowledged that limited understanding of their patients’ nondialysis burdens affected their ability to individualize care. As such, patients experienced a spectrum of isolation. Some patients intentionally isolated themselves (e.g. not disclosing information, separating their two ‘worlds’), while others experienced isolation involuntarily due to a lack of resources (e.g. transportation, social support). Balancing dual lives presented challenges that permeated day-to-day activities, patient–provider relationships and the overall dialysis experience. Furthermore, patients and providers described limited opportunities to engage in conversation about patients’ competing priorities, even during care plan meetings. As a result, some patients described making unsupported, difficult trade-off decisions between dialysis care and life priorities. For example, one recounted anxiety when choosing between attending and skipping treatments to be with his hospitalized wife.

Acknowledging an evolving identity. Some patients distinguished between their existences before and after starting dialysis, describing how dialysis robbed them of their former selves and/or future opportunities. However, others refused to allow dialysis to affect their core identities, noting that it only caused them to reprioritize. All patients developed coping strategies and made lifestyle modifications after initiating dialysis. This evolution was ongoing and emotionally draining. For some, infrequent provider acknowledgement and/or limited understanding of these struggles influenced how they interacted with their care providers. For example, one patient stated ‘I just keep it to myself because [the care team is] not really going to put forth an effort’. These feelings were exacerbated when medical recommendations did not align with patient priorities.

Respecting the individual as a whole person. All participants expressed the significance of and desire to acknowledge individuals as whole people with multifaceted lives, not merely patients with kidney failure. Specifically, patients wanted to be regarded as more than a number or laboratory value, they wanted respect for their identities outside of the dialysis context. Care providers appreciated that showing genuine interest in patients as human beings might influence patient willingness to communicate more openly about a range of subjects. Moreover, providers felt their jobs would be more satisfying if they were better able to focus on the whole person rather than system-imposed artificial outcomes.

Increasing individualization to enhance care. All participants felt that supporting patients in reaching personal goals might increase satisfaction with dialysis care and plans of care, enhancing overall well-being for patients and care team members alike. In fact, some providers proffered examples of when such support improved patient activation while simultaneously building team rapport (e.g. coordinating transportation to a golf course and following up about the experience). Patients described dialysis care as more meaningful when centered on their individual needs and priorities. Care providers desired to offer such care but expressed a need for training to do so effectively. A few providers indicated that focusing on life goals was out of their practice scope, suggesting that social workers were better equipped to address nondialysis-related goals.

Overall, participants viewed ‘quality’ dialysis care as safe, effective medical care that is tailored to meet individual patient needs and priorities and delivered with an authentic, personal touch. All care providers, regardless of their views on professional role limitations, expressed interest in providing more person-centered dialysis care.

Person-centered care planning program development

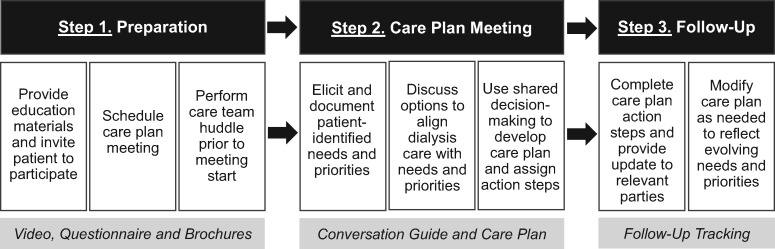

We used concept elicitation interview findings to develop an initial draft of a person-centered care planning program (Figure 2) [18–22]. Specifically, we focused on the principles of delivering care with compassion and respect, individualizing care and encouraging patient activation in care [11, 13, 14]. The program’s supporting materials were designed to equip patients and care team members with information and resources to use the interdisciplinary plan-of-care meeting to align dialysis care with patient priorities via shared decision-making. We used the term ‘priority’ rather than ‘life goal’ or ‘goal’, because the latter two did not resonate well with participants. Participants associated the term ‘life goal’ with lofty ideas (e.g. ‘play professional football’, ‘win the lottery’) and ‘goal’ with specific treatment outcomes such as laboratory values (e.g. phosphorus, Kt/V). During interviews, questions such as ‘What’s important to you?’ and ‘What matters to you?’ elicited patients’ aspirations more consistently than asking about ‘life goals’ (Supplementary data, Table S4).

FIGURE 2.

Proposed person-centered care planning approach. The figure displays the three primary steps involved in the proposed person-centered care planning approach. Each step is comprised of multiple actions, with associated materials to facilitate program implementation (light gray boxes).

To balance the patient-stated preference for brevity with the care provider–stated preference for specificity in written materials, we developed separate educational resources for patients and care team members. The brochures described the care planning approach and rationale and provided example strategies for incorporation into routine practice. Table 3 summarizes concept elicitation interview-derived data informing program development. We sought iterative stakeholder input on content relevance and program feasibility, responsively revising the materials 32 times prior to cognitive interviews.

Table 3.

Patient and care team suggestions for care planning program content updates a

| Element | Patients and care partner suggestions | Care team member suggestions |

|---|---|---|

| Length | Keep as short as possible | Keep as short as possible but not at the expense of contextualizing examples |

| Medium | Written and video | Written |

| Terminology | Avoid medical terminology without description(s), even for terms used routinely in health care (e.g. care plan, confidentiality) | Emphasize dialysis-specific examples and include descriptions and definitions for key terms (e.g. person-centered, shared decision-making) |

| Replace term ‘life goal’ with phrase ‘needs and priorities’ | Replace term ‘life goal’ with ‘personal goal’ and/or ‘needs and priorities’ | |

| Content | Provide example meeting topics, potential life priorities and more preparation questions | Provide a succinct program introduction, overview and rationale |

| Use empowering language about working together, creating/maintaining open communication and actively participating in the care plan meeting | Add a graphic that shows the differences in the problem- and priority-based approaches to care plans | |

| Explain the potential benefit of discussing both medical and personal priorities and concerns during care plan meetings | Provide references for evidence-based support of program implementation | |

| Explain why family and/or care partners might attend care plan meetings | Provide a step-by-step care plan meeting conversation guide to assist in eliciting patient priorities | |

| Emphasize confidentiality of discussions occurring at care plan meetings | Provide example patient priorities, barriers and care plan actions | |

| Provide note-taking space | Give examples of potential implementation challenges and possible solutions | |

| Logistics | Provide advanced notice of upcoming care plan meetings with options for location, timing and attendees | Use private settings for the care plan meeting and include family and/or care partners if desired by the patient |

| Perform a final review of the developed care plan and associated actions prior to meeting conclusion | Provide a recommended timeline for program implementation (e.g. meeting invitations, team huddles, follow-up) | |

| Provide a hard copy of the care plan for the patient and/or care partner to take home | Add guidance for conducting follow-up with patients and maintaining care team communication |

Data garnered from patient and care provider concept elicitation interviews.

Cognitive debriefing interview findings and responsive revisions

Table 4 summarizes cognitive interview findings and subsequent materials revisions. Overall, participants expressed agreement with and understanding of the information, with eight (89%) patients describing the brochure as ‘easy’ or ‘very easy’ to understand. Some patients recommended additional content. Specifically, four (44%) patients expressed interest in more information on care plan meeting confidentiality and five (56%) suggested additional questions to help patients prepare for meetings. All care providers said that inclusion of evidence-based data in the brochure provided justification for the approach, but five (63%) providers desired more examples of how to integrate patient-identified, nondialysis-related priorities into care plans. A few care providers requested clarification on implementation (e.g. timeline, roles and logistics). All expressed optimism for the potential of incorporating the program into practice so long as it was adapted to individual environments. In response to the materials, one physician said, ‘I will think more about how I talk with patients and what’s important to them’, and a social worker commented, ‘[There is] a possibility that we “can” do things differently’.

Table 4.

Cognitive interview key findings and responsive material updates a

| Element | Key findings | Responsive material updates |

|---|---|---|

| Patient materials | ||

| Content | Clear and succinct introduction needed | Created cover page with brief overview |

| Phrase ‘working for you’ unclear | Replaced with ‘meeting your needs’ | |

| Phrase ‘Don’t be afraid to speak up’ felt patronizing to some participants | Replaced with ‘Don’t be shy! Speak up! Your voice matters’. | |

| Term ‘person-centered’ difficult to understand | Replaced with ‘what matters most to you’ | |

| Term ‘individualized’ unclear | Updated to ‘unique to your needs and priorities’ | |

| Term ‘care plan’ rarely recognized without description or additional context | Added content on meeting frequency, attendees and discussion topic examples to orient patient to care plan meeting | |

| Formatting | Text-heavy, increase white space | Converted paragraph text into bullet points |

| Headers not easily noticeable | Bolded, colored and increased header font size | |

| Sequence of items unclear | Added numbering when applicable | |

| General comments | Physically difficult to distinguish from other documents received in clinic | Altered material dimensions and paper weight and added more color to clearly differentiate |

| Receiving a copy of the care plan may help patients remember the meeting discussion | Added, ‘Your care team will give you a copy of your care plan to take home’. | |

| Consistent communication is helpful, but patients often have different relationships with different care team members | Added, ‘You can always talk to a care team member. You don’t have to wait for another meeting’. | |

| Preparation questions helpful and relevant, but not comprehensive | Added questions about overall dialysis experience/ concerns and desired life changes | |

| Care team materials | ||

| Content | Lacks instructions to orient reader | Created cover page with brief overview |

| Seems bulky, difficult to skim easily | Added table of contents for easier navigation | |

| Redundant between sections | Collapsed information | |

| Example priorities, barriers, challenges and solutions need to be more realistic, less ideal | Used specific examples as recommended in various interviews | |

| Example solutions appear to be concrete answers, rather than suggested approaches | Edited to acknowledge variability in possible actions for individual patients and circumstances | |

| Formatting | Text-heavy, but should retain information | Changed paragraph text into bullet format |

| Conversation guide appears to be suggestions for engaging in discussion, rather than step-by-step instructions | Numbered steps to indicate a clear process by which to elicit patient preferences | |

| General comments | Timeline seems unclear; care teams would likely need to alter from clinic to clinic | Updated language to reflect a more flexible timeline to meet individual clinic needs |

| Lacking in disease-specific examples; contains too much emphasis on personal priorities | Added more examples of health-related patient priorities and possible actions | |

| Process requires effort, but would create meaningful patient interactions and more individualized care plans | Incorporated language around significance of helping patients achieve both their personal and medical goals | |

| Resources helpful for meeting preparation, patient engagement and team organization | Merged resources and process description into single care team packet | |

Data garnered from patient and care provider cognitive debriefing interviews.

In general, participants recommended some wording, formatting and content modifications (Table 4). In response, we revised the content to add contextualization, increase clarity, decrease burden and facilitate implementation. Specifically, we added an introduction to the patient brochure and instructions to the provider materials, increased the white space and incorporated specific examples of aligning dialysis care with patient priorities, among other changes. The resulting person-centered dialysis care planning program, My Dialysis Plan, aims to facilitate individualization of dialysis care plans and improve care experiences for patients and providers. Program materials include a short video introduction to spark patient activation and written materials to equip patients and providers with implementation strategies (https://unckidneycenter.org/kidneyhealthlibrary/my-dialysis-plan/) (Supplementary data).

DISCUSSION

Our findings provide insight into some of the challenges and opportunities in aligning dialysis care with patient priorities. Participants recognized that dialysis delivery system-level constraints (e.g. payer requirements, laboratory targets) and individual patient-level challenges (e.g. evolving identities, conflicting personal and medical priorities) contribute to disconnect between patients and dialysis care teams. That disconnect negatively influences the patient experience of care and the provider experience of providing it, often manifesting as one-sided decision-making that is unaligned with what matters most to patients. Participants expressed optimism that rooting interdisciplinary plans of care in patient priorities, as exemplified by My Dialysis Plan, may be an effective way to improve patient and clinician experiences. Subsequent interviews yielded evidence that the program and accompanying materials are acceptable and understandable to their target audiences.

Person-centered care improves adherence, communication and clinical outcomes among patients with multiple chronic medical conditions [27–34]. The approach can bolster patient care team relationships by promoting greater equality between the patient and care team; shared responsibility; development of a broader, more meaningful context to care and patient priorities as a foundation for shared decision-making [35]. As such, there is substantial interest in incorporating the philosophy into dialysis care as well as general medical care, but uptake has been slow [3, 10, 12, 13, 36]. A recent UK survey revealed that 40% of kidney physicians either sometimes or never seek to either identify patients’ personal goals or develop action plans to achieve them [37]. More than 60% of physician respondents reported sometimes or never asking patients what they wanted to focus on [37]. A Canadian analysis identified lack of time, infrastructure and ‘prescriptive’ care delivery as key barriers to implementing person-centered care in the dialysis setting [3].

Despite the challenges, a more individualized approach to dialysis care is desired and feasible [8, 9]. In fact, existing US regulations as well as international guidance require or recommend that interdisciplinary dialysis care teams develop individualized plans of care [38–40]. In practice, these plans are often health problem focused and centered on biochemical markers and other clinical targets rather than patient priority focused. Despite current limitations, the existing care planning process could support delivery of more person-centered care. Therefore we developed My Dialysis Plan to help dialysis care teams elicit and incorporate patient priorities into the interdisciplinary plan of care. For example, upon learning about a patient’s desire to play basketball again, the care team might refer her to physical therapy for strengthening. As the desired outcome is meaningful to the patient, she may be more inclined to attend appointments. Or, upon learning that a patient regrets starting dialysis [41], as the therapy has not improved his energy, the care team may initiate goals of care and advanced directive and end-of-life discussions during a care plan meeting. In both examples, individual patient priorities drive care decision-making.

We acknowledge that not all components of My Dialysis Plan may be equally useful to all clinics. As such, we encourage care teams to adapt the program to individual clinic environments. For example, in implementing My Dialysis Plan, it may be helpful to review and/or supplement the program with existing resources for dialysis care planning and shared decision-making (e.g. National Kidney Foundation Council of Nephrology Social Workers Care Planning Resource Toolkit [42]). In addition, other resources, such as Mandel et al.’s serious illness conversation guide for key care transitions [43] and Schell et al.’s communication framework for aligning treatment choices with patient goals and values for elderly and frail patients [44] may be helpful when discussing care transitions, end-of-life goals and advanced directives.

The strengths of our study include the number and diversity of participants as well as incorporation of interdisciplinary stakeholder input throughout program development. Study limitations relate to transferability to other settings due to inclusion of English-speaking, adult participants receiving maintenance hemodialysis in southeastern US academic institution–affiliated clinics with overrepresentation of individuals of black race. Second, care partner participants served as proxy reporters for patient perspectives, raising the potential for recall and proxy response bias. However, all care partners were family members, and concept elicitation interview questions were general rather than detail-oriented, minimizing these potential biases [45–47]. Related, we included only three care partners, necessitating further exploration of their perspectives in the future. Third, dialysis care planning approaches likely vary widely among clinics in the US and certainly internationally. Additionally, we developed English-language materials. Future work to capture non-English-speaking patient perspectives and identify necessary cultural adaptations is needed. Finally, we sought to include individuals with diverse educational experiences, yet there were no individuals with less than a high school education among cognitive interview participants.

In conclusion, we present a content-valid person-centered dialysis care planning program that aims to promote dialysis care individualization through optimization of the interdisciplinary plan of care. Future work must examine My Dialysis Plan implementation feasibility and capacity to improve patient experiences and outcomes.

SUPPLEMENTARY DATA

Supplementary data are available at ndt online.

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

The authors would like to thank all study participants (patients, care partners and providers) for sharing their time, perspectives and experiences on life goals and dialysis care planning. The authors also thank Kevin Fowler, David White, Lucy Menefee, Bradley Manton, Lisa Harvey, Shirley Franks and Colleen Chavis for their contributions while serving on the stakeholder panel.

FUNDING

This project was funded the American Institutes for Research, with support from the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation, for a patient-centered measurement pilot study (grant 0449700001). The funder had no role in the study design, data collection, analysis, manuscript writing or the decision to submit the report for publication. J.E.F. is supported by the National Institute of Diabetes, Digestive and Kidney Diseases (K23 DK109401).

AUTHORS’ CONTRIBUTIONS

J.E.F. and D.F. were involved in the conception and design. J.E.F. was responsible for oversight. J.E.F, A.D. and S.L.M. were responsible for analyzing data. A.D., D.F., S.L.M., J.W.M., A.V.K., D.A.D. and J.E.F. were involved in intellectual content, interpretation of data, article drafting and final approval.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST STATEMENT

In the last 2 years, J.E.F. has received speaking honoraria from the American Renal Associates, American Society of Nephrology, Dialysis Clinic, Inc., National Kidney Foundation and multiple universities as well as investigator-initiated research funding unrelated to this project from the Renal Research Institute, a subsidiary of Fresenius Kidney Care North America. J.E.F. is on the medical advisory board to NxStage Medical, now owned by Fresenius Kidney Care, North America and has received consulting fees from Fresenius Kidney Care, North America and AstraZeneca. J.W.M has written and published a book for patients on goal-oriented care from which he receives royalties. The remaining authors have nothing to disclose. The results presented in this article have not been published previously in whole or part, except in abstract form.

REFERENCES

- 1. Evangelidis N, Tong A, Manns B. et al. Developing a set of core outcomes for trials in hemodialysis: an International Delphi Survey. Am J Kidney Dis 2017; 70: 464–475 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Tong A, Manns B, Hemmelgarn B. et al. Establishing core outcome domains in hemodialysis: report of the Standardized Outcomes in Nephrology-Hemodialysis (SONG-HD) Consensus Workshop. Am J Kidney Dis 2017; 69: 97–107 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Lewis RA, Benzies KM, MacRae J. et al. An exploratory study of person-centered care in a large urban hemodialysis program in Canada using a qualitative case-study methodology. Can J Kidney Health Dis 2019; 6: 205435811987153. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Finkelstein FO. Performance measures in dialysis facilities: what is the goal? Clin J Am Soc Nephrol 2015; 10: 156–158 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Bevan MT. Nursing in the dialysis unit: technological enframing and a declining art, or an imperative for caring. J Adv Nurs 1998; 27: 730–736 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Goff SL, Eneanya ND, Feinberg R. et al. Advance care planning: a qualitative study of dialysis patients and families. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol 2015; 10: 390–400 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Flythe JE, Dorough A, Narendra JH. et al. Perspectives on symptom experiences and symptom reporting among individuals on hemodialysis. Nephrol Dial Transplant 2018; 33: 1842–1852 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services. End-Stage Renal Disease Patient-Reported Outcomes Technical Expert Panel Final Report 2017: 1–242. https://www.cms.gov/Medicare/Quality-Initiatives-Patient-Assessment-Instruments/MMS/TEP-Current-Panels.html (1 October 2019, date last accessed)

- 9. Chan CT, Blankestijn PJ, Dember LM. et al. Dialysis initiation, modality choice, access, and prescription: conclusions from a Kidney Disease: Improving Global Outcomes (KDIGO) Controversies Conference. Kidney Int 2019; 96: 37–47 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Brummel-Smith K, Butler D, Frieder M et al. , Institute of Medicine, Committee on Quality of Health Care in America. Crossing the Quality Chasm: A New Health System for the 21st Century. Washington, DC: National Academies Press, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- 11.American Geriatrics Society Expert Panel on Person-Centered Care. Person-centered care: a definition and essential elements. J Am Geriatr Soc 2016; 64: 15–18 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Freidin N, O’Hare AM, Wong SPY.. Person-centered care for older adults with kidney disease: core curriculum 2019. Am J Kidney Dis 2019; 74: 407–416 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Morton RL, Sellars M.. From patient-centered to person-centered care for kidney diseases. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol 2019; 14: 623–625 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Slater P, McCance T, McCormack B.. The development and testing of the Person-centred Practice Inventory – Staff (PCPI-S). Int J Qual Health Care 2017; 29: 541–547 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Collins A. Measuring What Really Matters Health Foundation. https://www.health.org.uk/sites/default/files/MeasuringWhatReallyMatters.pdf(12 October 2019, date last accessed)

- 16. Tong A, Sainsbury P, Craig J.. Consolidated criteria for reporting qualitative research (COREQ): a 32-item checklist for interviews and focus groups. Int J Qual Health Care 2007; 19: 349–357 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Sandelowski M. Combining qualitative and quantitative sampling, data collection, and analysis techniques in mixed-method studies. Res Nurs Health 2000; 23: 246–255 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Mold JW. Goal-Directed Health Care: Redefining Health and Health Care in the Era of Value-Based Care https://www.cureus.com/articles/5935-goal-directed-health-care-redefining-health-and-health-care-in-the-era-of-value-based-care (1 October 2019, date last accessed) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 19. Mold JW, Hamm R, Scheid D.. Evidence-based medicine meets goal-directed health care. Fam Med 2003; 35: 360–364 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Reuben DB, Tinetti ME.. Goal-oriented patient care—an alternative health outcomes paradigm. N Engl J Med 2012; 366: 777–779 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Schellinger SE, Anderson EW, Frazer MS. et al. Patient self-defined goals: essentials of person-centered care for serious illness. Am J Hosp Palliat Care 2018; 35: 159–165 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Tinetti ME, Naik AD, Dodson JA.. Moving from disease-centered to patient goals-directed care for patients with multiple chronic conditions: patient value-based care. JAMA Cardiol 2016; 1: 9–10 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Ericsson KA, Simon HA.. Verbal reports as data. Psychol Rev 1980; 87: 215–251 [Google Scholar]

- 24. Braun V, Clarke V.. Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qual Res Psychol 2006; 3: 77–101 [Google Scholar]

- 25. Braun V, Clarke V.. Successful Qualitative Research: A Practical Guide for Beginners . London: Sage, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 26. Phillippi J, Lauderdale J.. A guide to field notes for qualitative research: context and conversation. Qual Health Res 2018; 28: 381–388 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Hurn J, Kneebone I, Cropley M.. Goal setting as an outcome measure: a systematic review. Clin Rehabil 2006; 20: 756–772 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Stuck AE, Moser A, Morf U . et al. Effect of health risk assessment and counselling on health behaviour and survival in older people: a pragmatic randomised trial. PLoS Med 2015; 12: e1001889. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Nagykaldi ZJ, Tange H, De Maeseneer J.. Moving from problem-oriented to goal-directed health records. Ann Fam Med 2018; 16: 155–159 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Valentijn PP, Pereira FA, Ruospo M. et al. Person-centered integrated care for chronic kidney disease: a systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol 2018; 13: 375–386 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Turner-Stokes L. Goal attainment scaling and its relationship with standardized outcome measures: a commentary. J Rehabil Med 2011; 43: 70–72 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Rockwood K, Howlett S, Stadnyk K. et al. Responsiveness of goal attainment scaling in a randomized controlled trial of comprehensive geriatric assessment. J Clin Epidemiol 2003; 56: 736–743 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Tinetti ME, Naik AD, Dindo L. et al. Association of patient priorities-aligned decision-making with patient outcomes and ambulatory health care burden among older adults with multiple chronic conditions: a nonrandomized clinical trial. JAMA Intern Med 2019. doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2019.4235. [Epub ahead of print] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Blaum CS, Rosen J, Naik AD. et al. Feasibility of implementing patient priorities care for older adults with multiple chronic conditions. J Am Geriatr Soc 2018; 66: 2009–2016 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Waters D, Sierpina VS.. Goal-directed health care and the chronic pain patient: a new vision of the healing encounter. Pain Physician 2006; 9: 353–360 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.World Health Organization. WHO Framework on Integrated People-Centred Health Services https://www.who.int/servicedeliverysafety/areas/people-centred-care/en/ (5 October 2019, date last accessed).

- 37. Gair R, Steenkamp R, Caskey F. et al. Clinician Support for Patient Activation Measure (CS-PAM) Survey, Cohort 1 https://www.thinkkidneys.nhs.uk/ckd/wp-content/uploads/sites/4/2016/10/CS-PAM-Report-FINAL.pdf (12 December 2019, date last accessed)

- 38.Kidney Health Australia. Caring for Australasians with Renal Impairment (KHA-CARI) Guidelines https://kidney.org.au/health-professionals/support/kha-cari-guidelines (12 December 2019, date last accessed) [DOI] [PubMed]

- 39.Renal Association. Clinical Practice Guidelines: Haemodialysis https://renal.org/wp-content/uploads/2019/10/FINAL-HD-Guideline.pdf (12 December 2019, date last accessed)

- 40.Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services. ESRD Facility Conditions for Coverage https://www.cms.gov/Regulations-and-Guidance/Legislation/CFCsAndCoPs/Downloads/ESRDfinalrule0415.pdf (5 October 2019, date last accessed)

- 41. Davison SN. End-of-life care preferences and needs: perceptions of patients with chronic kidney disease. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol 2010; 5: 195–204 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.National Kidney Foundation Council of Social Workers. Care Planning Resource Toolkit https://www.kidney.org/sites/default/files/docs/cnswcareplanningresourcetoolkit.pdf (5 October 2019, date last accessed)

- 43. Mandel EI, Bernacki RE, Block SD.. Serious illness conversations in ESRD. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol 2017; 12: 854–863 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Schell JO, Cohen RA.. A communication framework for dialysis decision-making for frail elderly patients. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol 2014; 9: 2014–2021 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Milne DJ, Mulder LL, Beelen HC. et al. Patients’ self-report and family caregivers’ perception of quality of life in patients with advanced cancer: how do they compare? Eur J Cancer Care 2006; 15: 125–132 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Tomkins S. Proxy respondents in a case-control study: validity, reliability and Impact PhD dissertation. London: London School of Hygiene & Tropical Medicine, 2006. https://researchonline.lshtm.ac.uk/id/eprint/768483/ (5 October 2019, date last accessed)

- 47. Weinfurt KP, Trucco SM, Willke RJ. et al. Measuring agreement between patient and proxy responses to multidimensional health-related quality-of-life measures in clinical trials. An application of psychometric profile analysis. J Clin Epidemiol 2002; 55: 608–618 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.