Coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) has been described as a storm. It has affected over 215 regions/countries and the number of cases worldwide has reached 42,003,0601.

Singapore is an independent, multi-ethnic city-state with a population of 5,704,000. Having experienced severe acute respiratory syndrome (SARS) in 2003, the Singapore healthcare and surveillance systems have enhanced its pandemic preparedness responses. Despite coping and adapting well to contain the first wave of COVID-19, the systems were put to the test with an increase in the percentage of untraceable transmission within the community and widespread transmission among the migrant worker population. As of October 23, the city-state has recorded 57,941 cases of COVID-19 infection [1]; of this, 94.04% (n=54,492) were linked to migrant workers living in dormitories [2]. The nation's fatality rate of 0.05% is below global average (4%) [1]. Since the initiation of a nation-wide stay-at-home measure (circuit breaker) on April 7, the number of new cases and unlinked cases in the community has decreased significantly. Public health interventions such as contact tracing, enhanced surveillance testing in the dormitories have also lead to earlier detection and quarantine, thus preventing further uncontrolled transmission among migrant worker living in the dormitories [3].

While Singapore has made significant attempts to strengthen its epidemiological response to pandemic crises, it is uncertain whether the society is sufficiently resilient from the perspective of public health emergency preparedness, public hygiene practices as well as civic-mindedness. Singapore's experience thus far suggests that efficient and capable healthcare and surveillance systems alone are not sufficient to ensure success in the containment of a pandemic. The current COVID-19 pandemic has shaken the international system with tremendous impact on the public health system, and the daily lives of all individuals.

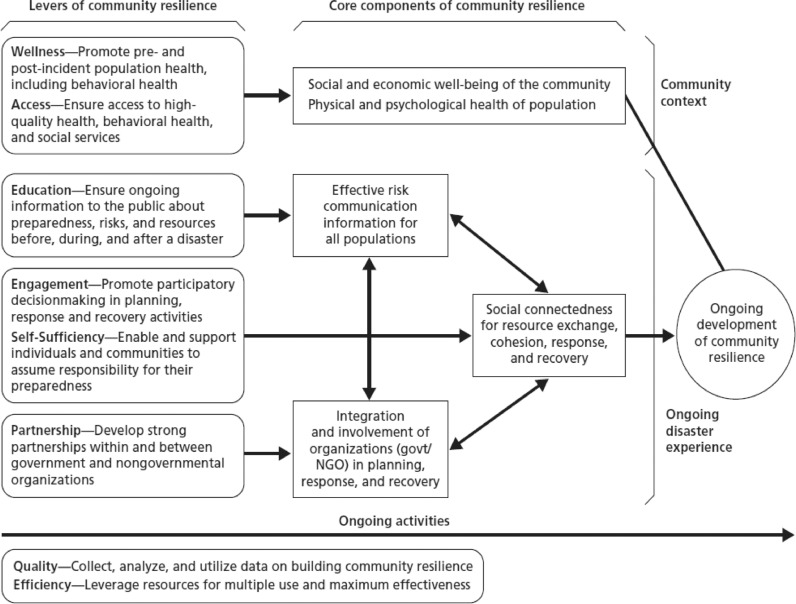

Community resilience as a framework can help us to better understand a community's persistent capacity to overcome and rebound from adversity. Based on the conceptual framework by Anita Chandra and colleagues [4], components of community resilience include a number of domains: physical and psychological health, communication, social connectedness and integration and involvement of organisations (Fig. 1). An equally important element that has not been emphasised sufficiently in this framework, is civic-mindedness and social responsibility [5,6]. Indeed, collective responsibility, and the sacrifice of individual desires, is key in fighting COVID-19 [7,12], especially in the protection of vulnerable and at-risk populations.

Fig. 1.

Components community resilience (extracted from Anita Chandra and colleagues [4]).

In this commentary, we describe Singapore's ongoing government policies and community efforts in combating COVID-19. We highlighted specific milestones related to the spread of COVID-19, and the enactment of safety measures in Singapore (Table 1), and areas that can be strengthened to enhance the community's preparedness in responding to future infectious disease outbreaks are also discussed.

Table 1.

| Date | Events |

|---|---|

| Jan 3 | Implementation of temperature screening for all inbound travellers from Wuhan |

| Jan 22 | Temperature screening was expanded to all travellers coming in from China Quarantine measures were extended to travellers with travel history to China within 14 days and displayed symptoms it is announced Anyone with acute respiratory infection who had been to any hospital in China within 14 days were isolated in hospital in Singapore Multi-ministry task force formed |

| Jan 23 | First confirmed case was warded at Singapore General Hospital, contact tracing began Temperature screening was implemented at all sea and land checkpoints |

| Jan 27 | Children and pre-school employees in Singapore were given mandatory 14-day leave of absence (LOA) if they had travelled to mainland China Singaporeans were advised against making non-essential trips to the Hubei province |

| Jan 29 | All visitors with recent travel history to Hubei or with passports issued in Hubei were not allowed to enter or transit in Singapore |

| Feb 1 | New visitors of any nationality with recent travel history to mainland China were not allowed to enter or transit in Singapore from 11.59pm on Feb 1 Four masks per household were handed out by the government, with advice to wear the masks only when unwell and visiting a doctor |

| Feb 4 | First cluster at Yong Thai Hang medical hall |

| Feb 7 | Disease Outbreak Response System Condition (DORSCON) level was raised to orange after more local cases emerged without links to previous cases or travel history to mainland China Workplaces were advised to carry out temperature screening and schools suspended inter-school and external activities till the end of the March school holidays Panic buying in supermarkets |

| Feb 10 | The Ministry of Manpower (MOM) ordered all dormitories to step up cleaning and precautionary measures All mass activities were suspended and the use of common dormitory facilities were staggered |

| Feb 17 | A new stay-home notice was announced - a person on a stay-home notice cannot leave their residence for 14 days All Singapore residents and pass holders returning from mainland China must complete a 14-day stay-home notice |

| Feb 25 | Contact tracing team finds a link between the Life Church and Missions and the Grace Assembly of God clusters First time serological testing was used to uncover a COVID-19 patient, who recovered before he/she was tested for the disease |

| Mar 3 | All travellers from Iran, Northern Italy and South Korea were not allowed to transit or enter Singapore |

| Mar 10 | Senior centric activities were suspended for 14 days from Mar 11 |

| Mar 12 | Mosques in Singapore were closed temporarily, after 90 Singaporeans attended a mass religious event in Kuala Lumpur that had been linked to dozens of cases in other countries |

| Mar 13 | Safe distancing measures were announced All ticketed cultural, sports and entertainment events with 250 participants or more were deferred or cancelled |

| Mar 15 | Anyone with recent travel history to ASEAN countries, Japan, Switzerland or the United Kingdom were issued a 14-day stay-home notice |

| Mar 18 | All new and present work pass holders had to receive approval from MOM before coming back to Singapore Upon arrival, stay-home notice must be served Singaporeans were advised to defer all travel abroad |

| Mar 20 | Stricter safe-distancing measures were rolled out in Singapore |

| Mar 21 | Singapore announced first 2 deaths |

| Mar 22 | All short-term pass holders were barred from entering or transiting in Singapore |

| Mar 26 | All entertainment venues, places of worship, attractions and tuition centres were closed. Restrictions were put in place at malls, museums and attractions. F&B outlets must ensure sufficient separation of dine-in areas |

| Mar 27 | Remaining public places must reduce crowd density to one person per 16 square meters |

| Mar 30 | First cluster detected at migrant workers dormitory |

| Apr 3 | Prime Minister Lee Hsien Loong announced a “circuit breaker” would run from Apr 7 to May 4. Only essential services could keep their premises open, and all schools were and students shifted to home-based learning Masks should be used when people leave the house for essential needs |

| Apr 7 | Circuit breaker commenced |

| Apr 12 | Stiffer penalties were introduced for those who continue to flout the rules –no more written warnings and a S$300 fine for the first offence |

| Apr 14 | Mask-wearing outside of one's house was mandatory |

| Apr 21 | Extension of circuit breaker till June 1. The measures were also tightened, with barber and bubble teashops closing |

| Apr 30 | Changi Airport Terminal 2 suspended operations for 18 months |

| Jun 1 | The circuit breaker ended and Singapore entered Phase One of reopening. Parents and grandparents could receive up to two visitors at once, from the same household |

| Jun 2 | Schools re-opened, but only graduating students to attend daily lessons |

| Jun 19 | Singapore moved to Phase Two of reopening. Dining-in was permitted, and households could receive up to five visitors |

1. Physical health by population segments

The Ministry of Health of Singapore responded to the pandemic with a comprehensive medical strategy to detect COVID-19 early, reduce community-based transmission and ensure those infected receive prompt treatment [8]. Singapore employed a test-isolate-quarantine-contact trace strategy to reduce community-based transmission [9]. At the start of the pandemic, only public hospitals were equipped to carry out screening and diagnostic tests for the virus. The capacity was expanded to include Public Health Preparedness Clinics, which comprised a consolidation of private primary care clinic to respond to public health emergencies. These clinics, were activated to perform COVID-19 tests, provide investigations and subsidised treatment for those with respiratory symptoms such as such as fever, cough, sore throat and runny nose [10].

As part of the medical strategy, community partners (private general practitioners, private companies, volunteers) were engaged to provide care for clinically stable cases and to rapidly set up community facilities for healthcare use. For example, 9 out of 10 patients with COVID-19 were treated in community facilities instead of acute hospitals [11]. In addition, about 3,000 retired healthcare professionals worked alongside active healthcare professionals and military officers in these facilities to manage COVID-19 patients that were stable and clinically well [12]. This whole-of-society effort prevented the tertiary systems from being overwhelmed and kept fatalities rate low [13].

Strategies employed by the Singapore government had been successful in controlling the virus transmission among citizens and permanent residents. However, widespread transmission within the migrant worker population highlighted the danger of underestimating the risk of contagion among vulnerable and hidden groups of people within the community. World Health Organisation (WHO) defines community as groups of people that may or may not be spatially connected, but share common interests, concerns or identities [14]. In the case of a pandemic, the definition of a community is no longer theoretical but essentially determines the scope, coverage and impact of the policies across the population segments. A common definition of community should be adopted across government agencies and organisations. Such adoption ensures that all segments of the population will be covered by government policies and included for public health emergency preparedness training [15,16].

In Singapore, the foreign workforce, accounts for 24% (1,351,800) of the total population [17], [18], [19]. Of which, 23.9% (323,000) of these migrant workers reside in dormitories, which are often cramped. In addition, these workers work in high-density and pressure-packed environments. Evidence had shown that a complex interplay of factors (e.g. socio-economic factors, living conditions, financial factors, language and cultural barriers to healthcare access, behavioural risks) often leads to a higher risk of infectious disease spread among migrant workers [20,21]. For example, a survey reported low awareness of healthcare insurance among migrant workers and majority of them delay in seeking medical care and continued to work while sick [14]. Separately, it was reported that migrant workers lived in cramped and ill-ventilated rooms with limited space in communal areas such as kitchens are toilets and subpar hygiene. These structural issues in terms of housing and welfare coupled with low health awareness encouraged infectious disease outbreak [22], [23], [24]. Further, these conditions made it challenging to implement safety measures and for migrant workers to adhere to the measures implemented. Hence, apart from existing regulations (e.g., pre-employment testing, vaccination, routine medical examinations etc.), addressing behavioural factors related to hygiene and health-seeking behaviours, and providing timely medical access are important immediate policy responses to the gaps identified during the pandemic. Specifically, continuous education on personal hygiene, increasing the awareness and knowledge on healthcare insurance coverage and entitlement, encouraging them to seek medical help early, communicated in their native languages, and making healthcare more accessible, are of paramount importance. For example, regional healthcare centres have been set up within dormitories to improve access to medical care [25]. Previously, migrant workers need to travel out of their dormitories to seek medical treatment. These newly set up medical centres greatly improve medical access to the migrant workers, further encouraging early treatment. For migrant workers who do not reside within the dormitories, telemedicine has also been made available for them [25]. To alleviate worries on healthcare costs, consultation fees for acute respiratory illness, acute and chronic conditions have been waived. Medication, and treatment for acute respiratory illness are also provided at no costs to the workers [25]. Addressing concerns on healthcare costs, bringing healthcare nearer to them and raising the awareness of the migrant workers, helped encourage early medical treatment and will guard against future infectious disease outbreaks. At the systems-level, attention to the design of the dormitories for migrant workers, ensuring sufficient ventilation and space in the communal areas (e.g., toilets, kitchen, living space), limiting the number of people in each bedroom and upkeeping hygiene standards of the living quarters will also be crucial. Rethinking and raising the standards of living spaces for migrant workers in the post-pandemic world will reduce the risk of future infectious disease outbreaks, and ensure measures can be safely and easily implemented. Certainly, there are limits to relying on private, profit-motivated entities to be responsible for the building, maintenance of living spaces of the migrant workers as well as for their welfare [26]. Hence, apart on the reviews of laws on housing and living conditions of the migrant workers, frequent checks and heavier penalties from authorities will ensure dormitory operators upkeep the living standards of the migrant workers. Continuous engagement between migrant workers, private operators and government agencies will be key to addressing the difficulties and concerns (e.g. increasing operating costs) faced by different parties and make certain the standards of the living and welfare of the migrant workers can be sustainably maintained [26]. A crucial lesson learnt from the outbreak within the dormitories is that living spaces for any segments within the population should never be overlooked. In addition, accessible healthcare and healthcare concerns, especially of the vulnerable population should be addressed from the start. These are ongoing efforts to address modifiable factors to contain the spread of COVID-19 within the context of pandemic management, but addressing systemic factors will also be essential for building resilience for the society as a whole. Deploying and expanding preventive measures is a step forward in improving the physical health and welfare of this vital yet vulnerable population within our community, thus, reducing the risk of future infectious disease outbreak [20].

Besides attending to COVID-19 patients, the healthcare system continued to care for patients with chronic diseases and individuals with acute care needs. Medical communities in Singapore rapidly switched to the use of telemedicine to ensure the continuity in medical care while reducing crowding of patients in medical premises [27]. In support of video consultations, the Ministry of Health extended the use of Community Health Assist Scheme (CHAS) cards and Medisave (a national medical saving scheme) for patients with stable chronic conditions (diabetes, hypertension, lipid disorder, major depression, schizophrenia, bipolar disorder and anxiety) to pay for video consultations starting early April [28]. Doctors were required to undergo telemedicine e-training prior to the provision of video consultation. Video consultations were limited only to patients whom doctors had previous physical consultations, to assess patient's suitability for virtual consultations. No doubt the use video consultation had been a useful solution during this infectious disease outbreak. However, medical communities were aware that the use of technology in place of face-to-face- consultations would be challenging and deemed unnatural for some patients [29]. It should be highlighted that the success of novel telehealth platforms will require a careful selection based on factors such patient's age, interests, physical capabilities, functional independence, familiarity and access to technology [29].

2. Greater attention for psychological health

Apart from physical health, the COVID-19 pandemic also had an effect on emotional and social functioning of individuals. The uncertain nature of the crisis, imposition of unfamiliar public health measures that infringed upon personal freedoms, large financial losses, were among the major stressors contributing to widespread emotional distress and increased risk for psychiatric symptoms [30,31]. This crisis also resulted in more frequent relapses among those with mental illnesses [32], [33], [34]. The elderly, in particular, those who lived alone, were at high risk of depression and isolation with the implementation of physical distancing. Closure of schools and shifting to full home-based learning also resulted in increased anxiety among school going children, especially those from disadvantaged families.

Mental health interventions and responses remained largely slow and inadequate in Singapore. For example, allied health services (e.g., private counselling and social work) were not categorised as essential services during the initial period of the circuit breaker. This meant that individuals suffering from mental illnesses and those experiencing emotional distress were unable to seek professional help. During the same period of time, most workplaces were closed and full home-based learning were implemented among primary and secondary schools. This meant that working parents of young children had to juggle between working from home and preforming childrearing duties with little support. Closure of university and college campuses led to local students from dysfunctional homes returning to potential pressure-cooker environments [35] while international students were isolated within their small rooms [35]. These disruptions in academic and social life, uncertainties about examinations and graduation, as well as diminishing career prospects with a looming recession contributed to a sense of fear, worry and anxiety experience by the students [35]. Separately, while the national budgets (Unity, Resilience, Solidarity and Fortitude budgets) were intended to address the effects of COVID-19, it did not have any direct allocation of funds for mental healthcare support or research [31].

Recognising the profound and broad spectrum of psychological impact [36], a national hotline was subsequently established on April 10, along with other community-based hotlines [31], to provide emotional and psychological support for the public. This highlighted that a reactive policy might not be ideal. Instead, early investments in mental healthcare infrastructure, programmes and research to enhance the public's psychological preparedness were needed. For example, proactive identification of individuals at higher risk of psychological morbidities is necessary for early interventions [37]. Identification of vulnerable individuals (e.g., elderly who are living alone, individuals with existing mental health conditions, student populations, and migrant workers) also ensures that community-based organisations can frequently touch based with them to assess their emotional and mental well-being and to ensure that they are supported, especially during the COVID-19 period. Capacity building for community-based detection and management of mental health conditions has been ongoing as part of the National Mental Health Blueprint efforts. The pandemic spotlighted the need to accelerate some of these efforts. Education and training regarding psychosocial issues should be extended to community partners (e.g., general medical practitioners, community-based volunteers and community-based nurses, school teachers and university professors), who often act as the first line of support. Specifically, general medical practitioners can monitor psychosocial needs, deliver resources and psychological support for their patients, and if, needed, refer to the psychiatrists for further management [38]. In addition, community partners also play an important role in disseminating and communicating evidence-based resources related to mental health, mental health triage and referral and bereavement care to the public [37]. Adding up, these strategies will strengthen the community's mental health resilience and reduce the possibility of developing psychiatric morbidities [31].

Introduction of the circuit breaker meant that older persons were unable to take part in their usual social or exercise activities organised by the senior activity centres, day care centres. This meant that the older persons, especially those who live alone, are forced to stay home, experiencing social isolation during this period [39]. Anticipating the impact on the seniors, especially those living alone, staff working in the senior activity centres and community-based organisations, actively reached out to these vulnerable individuals and to check in on them. Government agencies have also started to provide assistance to seniors to pick up basic digital skills, as evidence have shown that those who engaged in communication via the use of technology (smartphone apps to message or video-call others) have a higher levels of well-being and lower sense of social isolation [39]. First, schemes were made available such that smartphones and internet plans are affordable to the seniors. Second, digital ambassadors have been deployed to various community centres, public libraries to encourage seniors to attend programmes to pick up and strengthen digital literacy skills. Further, redesigning living spaces, with an enclave of social support will enable seniors to age gracefully in the privacy of their own home, regardless of circumstances [40]. Intentionally reaching out to our seniors to empower them with digital knowledge, rethinking their living spaces, and continuously supporting them through existing social networks will ensure that our elderlies continue to be prepared for future public health emergencies.

During circuit breaker, Singapore schools shifted to full home-based learning. To ensure students on financial assistance schemes have adequate resources to access online learning and can be supervised and supported by their teachers, they received devices such as tablets, computers and dongles for internet access. Despite the additional support from Ministry of Education and community-based organisations, children from disadvantaged backgrounds inevitably still faced difficulties in adapting due to a lack of conducive home environment or presence of a mature adult to facilitate learning [41]. In addition, students from disadvantaged homes may also have to worry about parents losing their job, not having enough to eat and fear over the possibility of domestic violence. In contrast, children whose parents have stable jobs, more flexible working hours, proper living quarters may have less worry and are able to enjoy more quality family time [42]. As such, early investments and educational support, especially for children from disadvantaged background is crucial to ensure they continue to be engaged in education, especially during a pandemic. Social service centres must also continue to take an active approach to reach out to the vulnerable children to provide necessary support to maintain their well-being. A holistic support from government agencies and community-based organisations is needed to prioritise education and welfare for children from disadvantaged families.

3. Economic well-being

The economic cost and consequences of this pandemic is serious and devastating. With worldwide travel restrictions and cities being in lockdown, the global economy has virtually come to a stop [43,44]. This has resulted in economic fallout leading to lasting implications on the quantity and quality of jobs worldwide. The international labour organisation estimated global unemployment to be more than 25 million, significantly more than the 2008 global financial crisis. Those who remain employed could experience a significant income loss [45]. Similarly, Singapore's economy has been severely affected. Singapore gross domestic product (GDP) has been forecasted to shrink between 4% and 7% for the year 2020. Retrenchments and unemployment are expected to go up. The unemployment rate is projected to spike above 5 per cent - higher than 4.1 per cent during the 2008 global financial crisis and 4.5 per cent during the SARS outbreak [46]. Disproportionately affected are those with low education attainment, doing manual jobs, front line service staff in food and beverage or hotel industry [47]. Lower-income workers - those who earn less than $3,000 per month - make up almost half who have experienced a fall in salaries. Within this group, 51 per cent saw their incomes fall by more than half [48]. Together, the evidence demonstrated that the effects of a crisis are unevenly distributed across the population segment. As such, sociodemographic factors must be taken into consideration when developing policies and support schemes.

In Singapore, having significant national reserves from past budgetary savings has allowed the government to swiftly introduce a series of initiatives to protect jobs, support households and companies. The Ministry of Finance unveiled a series of fiscal plans aimed at providing support for households, and workers, and to stabilise and protect businesses during this time of economic uncertainty. The Singapore government had dedicated close to S$100 billion through four different budgets that were introduced in quick succession: Unity, Resilience, Solidarity and Fortitude Budgets [49].

To mitigate the immediate effects of COVID-19 on unemployment and financial hardship, the budgets provided wage support pegged at 25–75% of the first US$3,369 (US$ 1: S$1.37) gross monthly salary and will be made available until March 2021. Other various schemes such as the Workfare Special Payment, the Self-Employed Person Income Relief Scheme (SIRS) and the COVID-19 Support Grant were also implemented to provide enable people to hold on to their jobs or to provide income support for households [50]. To expand employment and up-skilling opportunities, schemes such as SGUnited Jobs and Skills Package were created [51]. The National Jobs Council, which included representatives from the labour movement and business associations, had been set up to coordinate efforts from all the government agencies, with the primary objective to grow jobs and training opportunities for the people [52]. Through these efforts, the government aims to create 40,000 jobs, 25,000 traineeships and 30,000 paid skills training places. To re-skill and adapt the labour force to a more uncertain future, the plans included the provision of training opportunities for workers, and to build innovation, research and development capabilities as well as digitising public and private sectors.

Separately, foreign worker levy rebate have been introduced to waive foreign worker levies for companies [53]. The Singapore Ministry of Manpower encouraged companies to continue paying salaries to the migrant workers. Errant employers will not be able to apply from anymore support schemes and work pass privileges curtailed [53]. Furthermore, the Ministry also ensured that migrant workers continued to be paid while under quarantine and that their food, lodging and healthcare costs to be covered. Together, these frameworks were designed to ensure that the job support provided by the government is passed on to the workers and helped ensure job security for migrant workers [54].

The Monetary Authority of Singapore further introduced flexibility in loans and insurance premium payments for small and medium enterprises to allow businesses and enterprises more room to manoeuvre in the midst of current volatile economy [55]. The Ministry of Law also introduced the COVID-19 (Temporary Measures) Act to provide for a deferment of contractual obligations, suspension of rental payment for up to six months and prevents deposits paid from being forfeited [56]. These assistance schemes will help to cushion employees and companies and prevent complete fallout of the economies during this challenging period. Mortgage deferment was also allowed to support borrowers facing cash flow problems to allow the deferment of the repayment of the principal or both principal and interest up to 31 December 2020.

The Singaporean government has adopted a multipronged approach on the economic front to protect jobs and reboot the economy. Efforts from private and public sector as well as a nation of skilled, and capable people who seek continuous upgrade will support this endeavour. Given the positive correlation between economy, stable housing, individual productivity and health, taking care of a community's economic well-being, will influence its ability to bounce back from the COVID-19 induced economic downturn [57]. Moving forward, it will also be important to monitor the longer-term impact of this pandemic on various populations as the situation gradually improves. It difficult at this point to ascertain the longer-run effects of COVID-19, especially on the vulnerable population. However, our current lessons have pointed that a wholistic, inclusive population wide approach may buffer the people from the long drawn out effects of this pandemic and improve our long-term community resilience.

4. Effective communication strategies to combat fake news and to adopt a new behaviour

Fakes news and misinformation on COVID-19, have caused anxiety and confusion within the community [58]. To this, Singapore's approach has been to utilise various social media channels (e.g., WhatsApp, Telegram, Twitter), official website as well as traditional media communications to broaden access to information, to convey clarifications as well as debunk falsehoods in an efficient and timely manner [59]. Identification of source credibility, exposing denial, and corrections that explain causal relationships can be effective in countering misinformation [60]. However, it should be highlighted that debunking misinformation using fact checking and correction can be tedious due to the vast amount of false information. Hence, preventive strategies should be introduced during peacetimes to boost the public's media and information literacy by educating the public to spot fake news [61]. Enhancing media and information literacy involve empowering readers with critical thinking and analytical skills to evaluate the accuracy of the information as well as the navigation skills to find information online that is credible and reliable. These are essential skills in identifying fake news and misinformation [62,63]. In addition to these strategies, encouraging responsible sharing practices among individuals as well as instilling more stringent policies and artificial intelligence algorithms to prevent and detect fake news among social media platforms are useful preventive approaches [64].

Effective communication by the government, community leaders or community-based organisations plays an influential role in changing behaviours. As such, engaging perceived trusted voiced for targeted audiences and establishing social norms and community support had been highlighted to be effective in changing behaviours [60]. In Singapore, the multi-ministry task force provided daily updates and advice on safety measures for the public. The trust in the government had a direct impact on the adoption of socially responsible behaviours [65]. In addition, to best persuade the target population, an understanding of their motivation and what appeals to them most, will be essential [60]. Messaging approaches may emphasise on the benefits to the recipient, focusing on protecting others, aligning with the recipient's moral values, appealing to social consensus or scientific norms [60]. In Singapore, messages to the elderly population to adhere to the safety measures were focused on the benefits to the recipient, highlighting that staying home during the circuit breaker period was for their personal safety. On the other hand, the message to the general population not only explained the science behind the measures but also highlighted that compliance kept the seniors safe. This two-prong message emphasised on the scientific explanation of the measures and at the same time, appealed to the recipient's moral values [66,67]. The communication strategy adopted by the Singapore government led to an overall general compliance of precautionary measures.

In summary, understanding what works for the target population and tailoring the message to the audience is essential for effective communication between the government and the public. Moving forward, leaders will also need to turn to psychological and behavioural sciences to examine what strategies can be employed to ensure the changed behaviour is sustained.

5. Civic-mindedness and responsibility

One of the main responses triggered during a pandemic is fear. Fear can result in changes in behaviour. If an individual feels helpless in dealing with the threat, it can result in defensive reactions and panic [68]. In times of chaos and uncertainties, people act blindly and excessively out of self-preservation. An example is the response of ‘panic-buying’ observed when the disease outbreak response system (DOSRCON) orange was announced in Singapore [69]. On the other spectrum, in the presence of threat, people may also exhibit optimism bias, where an individual believe that bad things are less likely to befall oneself [60,70]. This cognitive bias can result in a behaviour where people take fewer safety precautions or less likely to adhere to safety measures recommended [70]. For example, not wearing a mask in public or adhering to physical distancing. The negative emotions and reactions triggered by this pandemic, such self-centred interest, fear, sense of panic, optimism bias will override individuals’ sensibility, resulting in the violation of measures, negligently or knowingly [71], undermining the precautionary measures that have been implemented.

Civic-mindedness is a culture and involves a sense of responsibility towards one's community (local, national or global), to each other and the society [40,41]. In a community with strong civic-mindedness, people, individually and collectively feel empowered to do the right things [72]. This requires the society to try to preserve privacy and individual liberty while ensuring that individuals also strive to achieve more public good through good behaviour [72,73], ultimately gearing towards social and societal betterment.

In Singapore, numerous campaigns have been initiated over the years to create a culture and societal norm where people clean up after themselves as acts of graciousness and consideration for others [74], to improve public and personal hygiene. Schools have also implemented cleaning activities to help students cultivate good habits [75]. However, sustained progress in behaviour change and mind set shift toward a more conscientious, caring and compassionate society has yet to be achieved [76].

On the other hand, in Japan and Taiwan, it is a social norm and a sign of consideration for others, to wear a mask when one is unwell (with cold or flu) to avoid infecting others [77], [78], [79]. The Japanese regard civic-mindedness and responsibility as second nature as they believe that one should be conscious of cleanliness. For example, the Japanese commonly practice “cough etiquette” where they cough into a tissue and dispose of it properly as a sign of consideration [78,80]. Hand washing and sanitising is also a big part of the Japanese way of life where hand sanitisers are common sightings in offices and shops. It stems from a belief that one should be cleaned before interacting with the another party, to avoid passing on germs and viruses [78]. During the fight against the pandemic, the Taiwanese had also cooperated fully by complying with the measures implemented and follow physical distancing guidelines voluntarily [81], [82], [83]. This self-discipline is driven by the belief that everyone has an important role to play in fighting this pandemic. The high level of civic-mindedness and responsibility that the Taiwanese and Japanese have been known for is translated in their habits and behaviour, and has played a key role in the containment of the virus.

People's behaviour is often influenced by social norms such as perceived action of the others or is also regulated by moral norms and values. Social enforcement encouraged people to embrace and internalise shared guidelines, making them motivated to do what is considered right while avoiding behaviours that seem wrong, and not having to not rely on law enforcements [84]. As such, it may be effective for local campaign messaging to incorporate morality, cooperation, kindness and compassion to encourage pro-social behaviours, thereby improving civic-mindedness and responsibility among individuals. Moving forward, healthcare officers and policy makers will need to draw on evidence from behavioural and social sciences to enhance communication on improving civic-mindedness of the people.

6. Social connectedness and integration and involvement of organisations

Empowerment of individuals, developments of social networks, and partnerships among organisations are major components of community resilience. During an acute phase of an emergency, essential items (e.g.: masks, hand sanitisers, first aid equipment) may be unavailable. Under such circumstances, leveraging on empowered individuals and available resources within the community will be an effective solution. In the initial period of COVID-19, face masks and sanitisers were in short supply. In response, individuals in the local community banded together to sew and distribute reusable masks, especially for children and vulnerable populations. In residential buildings, residents had also taken the initiative to strap alcohol wipes and bottles of hand sanitisers in elevators for community use [85]. These community efforts played a role in alleviating public anxiety during uncertain times and were excellent examples of empowered and connected individuals assuming responsibility during a crisis period. Individuals and organisations in Singapore had also initiated various activities, such as food delivery to students on quarantine and migrant workers, providing electronic devices to low-income families with children, checking in on vulnerable populations, providing grocery shopping services for senior citizens. Continuous efforts to build on social cohesion and forging a sense of common identity and commitment for the community will translate to a sense of collaboration. This will ensure that individuals continue to look out for each other to strengthen the resilience of the community.

Strong partnership between community-based organisations and government agencies are key to provide integrated care for the community. Often, community-based organisations have a good understanding of the social demographics and needs of the local population. This meant that they were able to identify the most vulnerable and actively reach out to them. For example, while many of the community-based programmes were suspended during the circuit breaker period, these organisations continued to provide weekly phone or face-to-face checks on frail or homebound seniors who live alone or lack a competent caregiver [86]. In addition, a strong rapport between community-based organisations and residents meant they are best positioned to effectively communicate best practices to empower residents. Thus, partnerships between government agencies partnerships and community-based partners will ensure information from healthcare systems and government agencies will be effectively communicated to the intended population [87]. An exemplary example of essential inter-agency cooperation was the contact tracing teams of the Ministry of Health, Singapore Police Force, Singapore Armed Forces, and volunteers for the purposes of rapidly determining the links between individuals confirmed with COVID-19 and their contacts. Similarly, Singapore's biomedical research and laboratory community were quickly mobilised and worked together to develop the world's first SARS-CoV-2 serological test to rapidly detect neutralising antibodies without need for containment facilities or live biological materials [88]. Put together, close collaboration between community-based agencies and government agencies are essential in providing prompt assistance to the public and in tackling any crisis.

7. Summary

This experience provided important reminders and lessons for Singapore for managing the effects of future infectious disease outbreaks that might be applied to other countries. First, the outbreaks that occurred within the dormitories were an important caution, in particular to resource limited, low- or middle-income countries with a larger congregation of people living in informal housing [89]. Second, continuous investment in the public health surveillance and health systems, will ensure that the systems are prepared for any future outbreaks. Close collaborative efforts between private and public healthcare institutions during this pandemic demonstrated the importance of enhancing cohesiveness within the local healthcare system. This strong partnership added much-needed bed space and manpower [90]. This has been key in keeping COVID-19 death rate low while effectively managing the rate of infection in the community. Third, clear and up-to-date accessible communication between government agencies and the public, had been key in reducing anxiety and confusion about safety measures introduced in the community. Fourth, cultivating a culture of strong community cohesiveness has led to the majority of the public adhering to safe distancing measures and to act in a more sustainable manner, especially during this pandemic [91].

These lessons learnt are clear examples on the need to build community resilience during peace time. Efforts in building community resilience can be focused into 4 main areas – physical and psychological health, economic well-being, communication, social connectedness and integration and involvement of organisations, with the addition of civic-mindedness and responsibility. Investments in these areas will be crucial in helping communities mitigate challenges, unite individuals to bounce back from the gravest of adversities. Moving forward, more research will also be needed to examine the longitudinal psycho-socio- and community impact of COVID-19. A holistic understanding of the coping mechanism of the community, in particular the vulnerable and at-risk groups during this pandemic will inform policy and practice to enhance future public health responses and supportive programmes.

Author contributions

YWF wrote the manuscript. YWF, TWS contributed to content development of the manuscript. All authors critically revised the manuscript and reviewed the final version.

Declaration of Competing Interest

The authors declare no competing interests.

References

- 1.worldometer. COVID-19 Coronavirus pandemic. 2020 [cited 2020; Available from: https://www.worldometers.info/coronavirus/-countries

- 2.Ministry of Health S. COVID-19 Situation report. 2020 [cited 2020; Available from: https://covidsitrep.moh.gov.sg/

- 3.gov.sg. COVID-19: Cases in Singapore. 2020 [cited 2020; Available from: https://www.gov.sg/article/covid-19-cases-in-singapore

- 4.Chandra A, Acosta J, Howard S, Uscher-Pines L, Williams M, Yeung D. Building community resilience to disasters: a way forward to enhance national health security. Rand Health Q. 2011;1(1):6. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Health TR. The RAND corporation is a nonprofit institution that helps improve policy and decision making through research and analysis. 2011 [cited 2020; Available from: http://www.rand.org

- 6.Maak T. The COVID-19 responsibility we all own. 2020 [cited 2020; Available from: https://pursuit.unimelb.edu.au/articles/the-covid-19-responsibility-we-all-own

- 7.Woon W. Why responsibility must come before freedom in Singapore's fight against Covid-19. 2020 [cited 2020; Available from: https://www.todayonline.com/commentary/why-responsibility-must-come-freedom-singapores-fight-against-covid-19

- 8.Health Mo. Comprehensive Medical Strategy for COVID-19. 2020 [cited 2020; Available from: https://www.moh.gov.sg/news-highlights/details/comprehensive-medical-strategy-for-covid-19

- 9.Ng Y LZ, Chua YX, Chaw WL, Zhao Z, Er B, Pung R, Chiew CJ, Lye DC, Heng D, Lee VJ. Evaluation of the effectiveness of surveillance and containment measures for the first 100 patients with COVID-19 in Singapore — January 2–February 29, 2020. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2020;69:6. doi: 10.15585/mmwr.mm6911e1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Health Mo. I am showing respiratory symptoms (like a cough, runny nose or fever), where should I go. 2020 [cited; Available from: https://www.gov.sg/article/i-am-showing-respiratory-symptoms-where-should-i-go

- 11.Kurohi R. 2020. 9 in 10 coronavirus patients in Singapore housed in community facilities.https://www.straitstimes.com/singapore/9-in-10-coronavirus-patients-housed-in-isolation-facilities [cited 2020; Available from: [Google Scholar]

- 12.Chua N. Covid-19: S'pore seeking volunteers from 'all walks of life' to support healthcare workers. 2020 [cited 2020; Available from: https://mothership.sg/2020/04/healthcare-volunteers-all-walks/).

- 13.Ministry of Health S. Ministerial Statement by Mr Gan Kim Yong, Minister for Health, At Parliament, On the Second Update On Whole-of-government Response to Covid-19, 4 May 2020. 2020 [cited 2020; Available from: https://www.moh.gov.sg/news-highlights/details/ministerial-statement-by-mr-gan-kim-yong-minister-for-health-at-parliament-on-the-second-update-on-whole-of-government-response-to-covid-19-4-may-2020

- 14.Organization WH . 7th Global Conference on Health Promotion. 2009. https://www.who.int/healthpromotion/conferences/7gchp/track1/en/ Track 1: Community empowerment[cited 2020; Available from: [Google Scholar]

- 15.Staff G-i-A. Safeguarding foreign workers in Singapore. 2019 [cited 2020; Available from: https://lkyspp.nus.edu.sg/gia/article/foreign-domestic-workers

- 16.Anita Chandra JDA, Stefanie Howard, Lori Uscher-Pines, Malcolm V. Williams, Douglas Yeung, Jeffrey Garnett, Lisa S. Meredith. Building comunity resilience to disasters: a roadmap to guide local planning. 2011 [cited 2020; Available from: https://www.rand.org/pubs/research_briefs/RB9574.html [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 17.Sreenivasan V. Singapore firms and workers should seek new normal. 2020 [cited; Available from: https://www.straitstimes.com/business/economy/singapore-firms-and-workers-should-seek-new-normal

- 18.Department of Statistics S. Singapore population. 2020 [cited; Available from: https://www.singstat.gov.sg/modules/infographics/population

- 19.Manpower Mo. Foreign workforce numbers. 2020 [cited 2020; Available from: https://www.mom.gov.sg/documents-and-publications/foreign-workforce-numbers

- 20.Sadarangani SP, Lim PL, Vasoo S. Infectious diseases and migrant worker health in Singapore: a receiving country's perspective. J Travel Med. 2017;24(4) doi: 10.1093/jtm/tax014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Ang JW, Koh CJ, Chua BW, Narayanaswamy S, Wijaya L, Chan LG. Are migrant workers in Singapore receiving adequate healthcare? A survey of doctors working in public tertiary healthcare institutions. Singapore Med J. 2019 doi: 10.11622/smedj.2019101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Zhuo T. Don't blame migrant workers for coronavirus spread. 2020 [cited 2020; Available from: https://www.straitstimes.com/opinion/dont-blame-migrant-workers-for-coronavirus-spread

- 23.Ng Jun Sen JO. The Big Read: Solving Singapore's foreign workers problem requires serious soul searching, from top to bottom. 2020 [cited 2020; Available from: https://www.channelnewsasia.com/news/singapore/coronavirus-covid-19-foreign-workers-big-read-dormitories-12718880

- 24.Zhang LM. 80 breaches found at purpose-built dorms annually for the past 3 years: MOM. 2020 [cited 2020; Available from: https://www.straitstimes.com/singapore/80-breaches-found-at-purpose-built-dorms-annually-for-the-past-three-years-mom

- 25.Ministry of Manpower S. Advisory on continued medical support for migrant workers. 2020 [cited 2020; Available from: https://www.mom.gov.sg/covid-19/advisory-on-continued-medical-support-for-migrant-workers

- 26.Liang LY. Lessons from high-density dorms spark new approach. 2020 [cited 2020; Available from: https://www.straitstimes.com/singapore/lessons-from-high-density-dorms-spark-new-approach

- 27.Oza A. Commentary: Making a trip to the clinic is not the only way to get medical treatment during COVID-19. 2020 [cited; Available from: https://www.channelnewsasia.com/news/commentary/tele-health-medicine-safe-to-visit-hospitals-doctors-covid-19-12865540

- 28.Wei TT. Coronavirus: Patients can tap Chas and Medisave for video consultations for chronic conditions. 2020 [cited 2020; Available from: https://www.straitstimes.com/singapore/health/coronavirus-patients-can-tap-chas-and-medisave-for-video-consultations-for-chronic

- 29.Dinesen B, Nonnecke B, Lindeman D, Toft E, Kidholm K, Jethwani K. Personalized telehealth in the future: a global research agenda. J Med Internet Res. 2016;18(3):e53. doi: 10.2196/jmir.5257. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Benson NM, Ongur D, Hsu J. COVID-19 testing and patients in mental health facilities. Lancet Psychiatry. 2020;7(6):476–477. doi: 10.1016/S2215-0366(20)30198-X. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Xiangyun L. Commentary: Our approach to mental health needs to change. COVID-19 will force us to. 2020 [cited 2020; Available from: https://www.channelnewsasia.com/news/commentary/covid-19-may-worsen-mental-health-in-singapore-12703566

- 32.Justin Ong NM. Covid-19: Impact on mental health under the spotlight, as MOH clarifies stance on treatment amid 'circuit breaker' Read more at https://www.todayonline.com/singapore/managing-mental-health-during-covid-19-moh-says-treatments-patients-not-essential-services. 2020 [cited; Available from: https://www.todayonline.com/singapore/managing-mental-health-during-covid-19-moh-says-treatments-patients-not-essential-services

- 33.Rachel Phua AHM. COVID-19: Worries about pandemic see more calls to mental health helplines. 2020 [cited; Available from: https://www.channelnewsasia.com/news/singapore/covid-19-fear-toll-mental-health-hotline-anxiety-singapore-12631710

- 34.Tan T. Anxiety and worry amid Covid-19 uncertainty. 2020 [cited 2020; Available from: https://www.straitstimes.com/singapore/anxiety-and-worry-amid-covid-19-uncertainty

- 35.Ho AHY. COVID-19 and social distancing: Impacts on youths, university and post-secondary students. 2020 [cited 2020; Available from: https://www.academia.sg/academic-views/covid-19-and-social-distancing-impacts-on-youths-university-and-post-secondary-students/

- 36.Teo J. Covid-19 will have a long-tail effect on mental health, experts predict. 2020 [cited 2020; Available from: https://www.straitstimes.com/singapore/health/covid-19-will-have-a-long-tail-effect-on-mental-health-experts-predict

- 37.Ho CS, Chee CY, Ho RC. Mental health strategies to combat the psychological impact of COVID-19 beyond paranoia and panic. Ann Acad Med Singapore. 2020;49(3):155–160. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Pfefferbaum B, North CS. Mental health and the Covid-19 pandemic. New Eng J Med. 2020;383(6):510–512. doi: 10.1056/NEJMp2008017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Han GY. Seniors felt less socially satisfied, more isolated during Covid-19 circuit breaker period: Survey. 2020 [cited 2020; Available from: https://www.straitstimes.com/singapore/lower-satisfaction-levels-higher-social-isolation-for-senior-citizens-during-circuit

- 40.Lin C. New flats for the elderly to be launched in February BTO exercise, with subscription to care services. 2020 [cited 2020; Available from: https://www.channelnewsasia.com/news/singapore/bto-flats-elderly-bukit-batok-care-services-assisted-living-13742262

- 41.Yeo S. A lost or more resilient generation? 6 ways Covid-19 changed childhood in Singapore. 2020 [cited 2020; Available from: https://www.straitstimes.com/lifestyle/6-ways-covid-19-changed-childhood-in-singapore-a-lost-or-more-resilient-generation

- 42.DAvie S. Covid-19 pandemic shows children's well-being and success depend on more than just what happens in school. 2020 [cited 2020; Available from: https://www.straitstimes.com/opinion/pandemic-shows-inequality-begins-at-home-for-students-learning

- 43.Whyman O. COVID-19 Risks outook: a preliminary mapping and its implications. 2020 [cited 2020; Available from: https://www.oliverwyman.com/content/dam/oliver-wyman/v2/publications/2020/may/covid-19-risks-outlook-a-preliminary-mapping-and-its-implications.pdf

- 44.OECD. OECD Policy Responses to Coronavirus (COVID-19), From pandemic to recovery: Local employment and economic development. 2020 [cited 2020; Available from: http://www.oecd.org/coronavirus/policy-responses/from-pandemic-to-recovery-local-employment-and-economic-development-879d2913/.

- 45.Ho O. Covid-19 jobs and skills package aims to save jobs, create new openings, help hard-hit groups, says DPM Heng. 2020 [cited; Available from: https://www.straitstimes.com/politics/three-thrusts-to-jobs-and-skills-package-saving-jobs-creating-new-openings-giving-more-help

- 46.Phua R. Retrenchments and withdrawn job offers: Singapore's labour market shows signs of COVID-19 strain. 2020 [cited; Available from: https://www.channelnewsasia.com/news/business/covid19-strain-labour-market-retrenchments-rescinded-job-offers-12665732

- 47.Ho G. Rethinking jobs for Covid-19 and beyond. 2020 [cited 2020; Available from: https://www.straitstimes.com/politics/rethinking-jobs-for-covid-19-and-beyond

- 48.Seow J. Lower-wage workers in Singapore hit hard by fallout of pandemic. 2020 [cited 2020; Available from: https://www.straitstimes.com/singapore/manpower/lower-wage-workers-here-hit-hard-by-fallout-of-pandemic

- 49.Liang LY. $33b set aside in Fortitude Budget, bringing Singapore's Covid-19 war chest to nearly $100 billion. 2020 [cited 2020; Available from: https://www.straitstimes.com/politics/parliament-33-billion-set-aside-in-fortitude-budget-bringing-covid-19-war-chest-to-nearly

- 50.Finance Mo. Jobs support scheme. 2020 [cited 2020; Available from: https://www.singaporebudget.gov.sg/docs/default-source/budget_2020/download/pdf/resilience-budget-enhanced-jobs-support-scheme.pdf

- 51.Singapore W. SGUnited jobs virtual career fair. 2020 [cited 2020; Available from: https://www.wsg.gov.sg/SGUnited.html

- 52.Seow J. National Jobs Council will create jobs and training opportunities on an unprecedented scale: Tharman. 2020 [cited 2020; Available from: https://www.straitstimes.com/singapore/manpower/national-jobs-council-will-create-jobs-and-training-opportunities-on-an

- 53.Ho O. Coronavirus: pass on jobs support to workers or lose future payouts, MOM warns employers. 2020 [cited 2020; Available from: https://www.straitstimes.com/singapore/manpower/coronavirus-pass-on-jobs-support-to-workers-or-lose-future-payouts-mom-warns

- 54.Ministry of Manpower S. Advisory on salary payment to foreign workers residing in dormitories. 2020 [cited 2020; Available from: https://www.mom.gov.sg/covid-19/advisory-on-salary-payment-to-foreign-workers

- 55.Singapore MAo. MAS and financial industry to support individuals and SMEs affected by the COVID-19 Pandemic. 2020 [cited 2020; Available from: https://www.mas.gov.sg/news/media-releases/2020/mas-and-financial-industry-to-support-individuals-and-smes-affected-by-the-covid-19-pandemic

- 56.Ng C. Coronavirus: New law offers relief over affected events and payments. 2020 [cited; Available from: https://www.straitstimes.com/singapore/new-law-offers-relief-over-affected-events-and-payments

- 57.Plough A, Fielding JE, Chandra A, Williams M, Eisenman D, Wells KB. Building community disaster resilience: perspectives from a large urban county department of public health. Am J Public Health. 2013;103(7):1190–1197. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2013.301268. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Mahmud AH. Government has debunked 40 instances of fake news on COVID-19: Iswaran. 2020 [cited 2020; Available from: https://www.channelnewsasia.com/news/singapore/government-debunk-fake-news-covid-19-iswaran-12700042

- 59.Hou Y, Tan YR, Lim WY, Lee V, Tan LWL, Chen MI. Adequacy of public health communications on H7N9 and MERS in Singapore: insights from a community based cross-sectional study. BMC Public Health. 2018;18(1):436. doi: 10.1186/s12889-018-5340-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Bavel JJV, Baicker K, Boggio PS, Capraro V, Cichocka A, Cikara M. Using social and behavioural science to support COVID-19 pandemic response. Nat Hum Behav. 2020;4(5):460–471. doi: 10.1038/s41562-020-0884-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Yahya Y. Teaching guidelines on how to spot fake news to be launched. 2018 [cited 2020; Available from: https://www.straitstimes.com/singapore/teaching-guidelines-on-how-to-spot-fake-news-to-be-launched

- 62.Jones-Jang S.M., Mortensen T., Liu J. Does media literacy help identification of fake news? Information literacy helps, but other literacies don't. Am Behav Sci. 2019 doi: 10.1177/0002764219869406. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Alice Huguet JK, Garrett Baker, Marjory S. Blumenthal. Exploring media literacy education as a tool for mitigating truth decay. 2019 [cited; Available from: https://www.rand.org/content/dam/rand/pubs/research_reports/RR3000/RR3050/RAND_RR3050.pdf

- 64.Gulizar Haciyakupoglu JYH, V.S. Suguna, Dymples Leong, and Muhammad Faizal Bin Abdul Rahman. Countering fake news a survey of recent global initiatives. 2018 [cited; Available from: https://www.rsis.edu.sg/wp-content/uploads/2018/03/PR180307_Countering-Fake-News.pdf

- 65.Singapore NTUo. NCID, NUS and NTU studies highlight the role of socio-behavioural factors in managing COVID-19. 2020 [cited 2020; Available from: https://media.ntu.edu.sg/NewsReleases/Pages/newsdetail.aspx?news=221cc9a8-f0cd-40ac-a837-c1caf19897b7

- 66.Today. Covid-19: PM Lee makes ‘special appeal’ to older S'poreans to stay home for their own safety. 2020 [cited 2020; Available from: https://www.todayonline.com/singapore/covid-19-pm-lee-makes-special-appeal-older-sporeans-stay-home-their-own-safety,

- 67.gov.sg. The science behind why masks help prevent COVID-19 spread. 2020 [cited 2020; Available from: https://www.gov.sg/article/the-science-behind-why-masks-help-prevent-covid-19-spread

- 68.Witte K, Allen M. A meta-analysis of fear appeals: implications for effective public health campaigns. Health Educ Behav. 2000;27(5):591–615. doi: 10.1177/109019810002700506. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Low Youjin AC. The big read: panic buying grabbed the headlines, but a quiet resilience is seeing Singaporeans through COVID-19 outbreak. 2020 [cited 2020; Available from: https://www.channelnewsasia.com/news/singapore/coronavirus-covid-19-panic-buying-singapore-dorscon-orange-12439480

- 70.Franco M. This bias explains why people don't take COVID-19 seriously. 2020 [cited 2020; Available from: https://www.psychologytoday.com/sg/blog/platonic-love/202003/bias-explains-why-people-dont-take-covid-19-seriously

- 71.Chan D. A toolkit to deal with negative reactions in the Covid-19 crisis. 2020 [cited; Available from: https://www.straitstimes.com/opinion/a-toolkit-to-deal-with-negative-reactions-in-the-covid-19-crisis

- 72.Ken ANY. Strong civic-mindedness key to achieving active citizenry. 2016 [cited; Available from: https://www.todayonline.com/voices/strong-civic-mindedness-key-achieving-active-citizenry

- 73.Diana Smart JWT, Ann Sanson. The development of civic mindedness in Australian adolescents. 2000 [cited; Available from: https://www.researchgate.net/profile/John_Toumbourou/publication/292124642_The_development_of_civic_mindedness_in_Australian_adolescents/links/5c6774d1299bf1e3a5abed58/The-development-of-civic-mindedness-in-Australian-adolescents.pdf

- 74.Council PH. Keeping Singapore clean. 2018 [cited 2020; Available from: https://www.publichygienecouncil.sg/about)

- 75.Yang C. All schools to have cleaning activities from January. 2016 [cited; Available from: https://www.straitstimes.com/singapore/education/all-schools-to-have-cleaning-activities-daily-from-january

- 76.Koh T. Five tests that Singaporeans must pass to be a truly First World people. 2019 [cited; Available from: https://www.publichygienecouncil.sg/reads/2019/12/23/1

- 77.Smith N. Social distancing is the norm in Japan. That's why COVID-19 spread is slow there. 2020 [cited; Available from: https://theprint.in/health/social-distancing-is-the-norm-in-japan-thats-why-covid-19-spread-is-slow-there/384498/

- 78.Steven John Powell AMC. What Japan can teach us about cleanliness. 2019 [cited; Available from: http://www.bbc.com/travel/story/20191006-what-japan-can-teach-us-about-cleanliness

- 79.Liu WT-yaK. Life with face masks, then and now. 2020 [cited 2020; Available from: https://focustaiwan.tw/society/202005115001

- 80.Making C. Japan takes hand washing to new level. 2009 [cited 2020; Available from: https://www.latimes.com/archives/la-xpm-2009-oct-16-fg-japan-clean-hands16-story.html

- 81.Sui C. 2020. In Taiwan, the coronavirus pandemic is playing out very differently. What does life without a lockdown look like?https://www.nbcnews.com/news/world/taiwanese-authorities-stay-vigilant-virus-crisis-eases-n1188781 [cited; Available from: [Google Scholar]

- 82.Everington K. Wearing face masks prevented spread of coronavirus in Taiwan: CECC. 2020 [cited 2020; Available from: https://www.taiwannews.com.tw/en/news/3927810

- 83.Yi-ching C. CORONAVIRUS/How Taiwan has been able to keep COVID-19 at bay. 2020 [cited 2020; Available from: https://focustaiwan.tw/society/202003160019

- 84.John Tooby LC. Groups in mind: the coalition roots of war and morality. 2010 [cited; Available from: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/267974874_Groups_in_Mind_The_Coalitional_Roots_oWar_and_Morality

- 85.Mohan ICM. 'The kampung spirit is still alive': Punggol residents step up amid coronavirus outbreak. 2020 [cited 2020; Available from: https://www.channelnewsasia.com/news/singapore/wuhan-coronavirus-singapore-virus-punggol-kampung-spirit-12397614

- 86.Matthew Loh KC. ‘Now the days seem longer’: with social activities halted, isolated seniors struggle to pass time 2020 [cited 2020; Available from: https://www.todayonline.com/singapore/now-days-seem-longer-social-activities-halted-isolated-seniors-struggle-pass-time

- 87.Ting CY. Coronavirus: Govt assures religious leaders that events and worship can continue, but with precautions. 2020 [cited 2020; Available from: https://www.straitstimes.com/singapore/coronavirus-govt-assures-religious-leaders-that-events-and-worship-can-continue-but-with

- 88.School DM. cPass™ SARS-CoV-2 neutralising antibody detection kit. 2020 [cited 2020; Available from: https://www.duke-nus.edu.sg/covid-19

- 89.Staff G-i-A. COVID-19: lesson learned? What comes next. 2020 [cited 2020; Available from: https://lkyspp.nus.edu.sg/gia/article/covid-19-lessons-learned-what-comes-next)

- 90.Vasoo LYSaS. Lessons from a pandemic: How Covid-19 is managed and prevented in Singapore. 2020 [cited 2020; Available from: https://www.straitstimes.com/singapore/lessons-from-a-pandemic

- 91.Khalik S. Lessons from one million Covid-19 deaths. 2020 [cited 2020; Available from: https://www.straitstimes.com/singapore/lessons-from-one-million

- 92.Goh T. Six months of Covid-19 in Singapore: A timeline. 2020 [cited 2020; Available from: https://www.straitstimes.com/singapore/six-months-of-covid-19-in-singapore-a-timeline

- 93.Yong M. Timeline: How the COVID-19 outbreak has evolved in Singapore so far. 2020 [cited 2020; Available from: https://www.channelnewsasia.com/news/singapore/singapore-covid-19-outbreak-evolved-coronavirus-deaths-timeline-12639444