Abstract

Background

Pregnant women and their neonates represent 2 vulnerable populations with an interdependent immune system that are highly susceptible to viral infections. The immune response of pregnant women to severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 and the interplay of how the maternal immune response affects the neonatal passive immunity have not been studied systematically.

Objective

We characterized the serologic response in pregnant women and studied how this serologic response correlates with the maternal clinical presentation and with the rate and level of passive immunity that the neonate received from the mother.

Study Design

Women who gave birth and who tested positive for immunoglobulin M or immunoglobulin G against severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 using semiquantitative detection in a New York City hospital between March 22, 2020, and May 31, 2020, were included in this study. A retrospective chart review of the cases that met the inclusion criteria was conducted to determine the presence of coronavirus disease 2019 symptoms and the use of oxygen support. Serology levels were compared between the symptomatic and asymptomatic patients using a Welch 2 sample t test. Further chart review of the same patient cohort was conducted to identify the dates of self-reported onset of coronavirus disease 2019 symptoms and the timing of the peak immunoglobulin M and immunoglobulin G antibody levels after symptom onset was visualized using local polynomial regression smoothing on log2-scaled serologic values. To study the neonatal serology response, umbilical cord blood samples of the neonates born to the subset of serology positive pregnant women were tested for serologic antibody responses. The maternal antibody levels of serology positive vs the maternal antibody levels of serology negative neonates were compared using the Welch 2 sample t test. The relationship between the quantitative maternal and quantitative neonatal serologic data was studied using a Pearson correlation and linear regression. A multiple linear regression analysis was conducted using maternal symptoms, maternal serology levels, and maternal use of oxygen support to determine the predictors of neonatal immunoglobulin G levels.

Results

A total of 88 serology positive pregnant women were included in this study. The antibody levels were higher in symptomatic pregnant women than in asymptomatic pregnant women. Serology studies in 34 women with symptom onset data revealed that the maternal immunoglobulin M and immunoglobulin G levels peak around 15 and 30 days after the onset of coronavirus disease 2019 symptoms, respectively. Furthermore, studies of 50 neonates born to this subset of serology positive women showed that passive immunity in the form of immunoglobulin G is conferred in 78% of all neonates. The presence of passive immunity is dependent on the maternal antibody levels, and the levels of neonatal immunoglobulin G correlate with maternal immunoglobulin G levels. The maternal immunoglobulin G levels and maternal use of oxygen support were predictive of the neonatal immunoglobulin G levels.

Conclusion

We demonstrated that maternal serologies correlate with symptomatic maternal infection, and higher levels of maternal antibodies are associated with passive neonatal immunity. The maternal immunoglobulin G levels and maternal use of oxygen support, a marker of disease severity, predicted the neonatal immunoglobulin G levels. These data will further guide the screening for this uniquely linked population of mothers and their neonates and can aid in developing maternal vaccination strategies.

Key words: antibody levels, asymptomatic infection, baby, convalescent infection, cord blood, COVID-19 infection, mother, mother-baby dyads, passive immunity, predictor, prevalence, symptomatic infection, time course

Introduction

As the novel severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2) spread rapidly through New York City in March 2020—the global epicenter of the disease at that time—the obstetrical unit within a New York City hospital implemented universal testing of all women admitted to the labor and delivery unit to screen this uniquely vulnerable patient population. During this peak of the pandemic, 10% to 15% of all women admitted to labor and delivery units in the New York City area tested positive for SARS-CoV-2 using reverse transcription polymerase chain reaction (RT-PCR) testing.1 , 2 An updated report from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention in October 2020 stated that pregnant women with symptomatic coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) infections were at an increased risk for intensive care unit admission, invasive ventilation, extracorporeal membrane oxygenation, and death.3 Additional prospective and retrospective studies have shown that pregnant women infected with SARS-CoV-2 are at an increased risk for other morbidities as well, including higher rates of cesarean delivery, increased postpartum complications (including fever, hypoxia, and hospital readmissions postdischarge) and placental pathology including fetal vascular malperfusion; however, it should be noted that the risk for premature delivery may still require further study.10, 11, 4, 5, 6, 7, 8, 9

AJOG at a Glance.

Why was this study conducted?

Previous studies on the serologic response to severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 viral infection have been focused on the general population but the timing and level of serologic response in pregnant women are not well characterized. The passive transmission of maternal antibodies to neonates have not been studied systematically at scale.

Key findings

Asymptomatic pregnant women mount a lower serologic response than symptomatic pregnant women. The timing of immunoglobulin M (IgM) and immunoglobulin G (IgG) antibody response levels peak at 15 days and 30 days after onset of coronavirus disease 2019 symptoms, respectively. The maternal IgG antibodies correlate positively with and predict the antibody levels of the neonates.

What does this add to what is known?

This study provides a comprehensive, semiquantitative analysis of the levels and timing of IgM and IgG antibodies in pregnant women. Mothers with higher antibody levels exhibit a higher likelihood of transferring antibodies to their neonates.

There has been a recent interest in serology testing as a means of detecting exposure to SARS-CoV-2, to limit disease spread, and to potentially predict outcomes.12, 13, 14 Studies have reported that nearly 100% of patients with confirmed SARS-CoV-2 will receive positive test results for immunoglobulin G (IgG) or immunoglobulin M (IgM) antibodies within 19 days of exposure, even after RT-PCR results revert to negative.15, 16, 17 Some data suggest that high levels of IgG are associated with more severe illness,18 whereas asymptomatic patients are more likely to convert to serology negative in the convalescent phase of infection.19 The protective nature of antibodies against SARS-CoV-2 against future infection is still unclear.20

Pregnant women and their neonates have a unique interdependent immune system. The interactions between the maternal immune system and fetal placenta result in changes that alter both the innate and adaptive host responses to infections.21 For this reason, current studies on the serologic responses to SARS-CoV-2 may not be applicable to the pregnant population. Studies to date have demonstrated the rate of serology positive results in pregnant women,22 , 23 but a detailed analysis of the timing and levels of the responses in these pregnant patients have not been well characterized.

Passive transfer of antibodies against SARS-CoV-2 has not been studied systematically beyond the demonstration of neonatal antibodies in a small number of cases, and it is not clear if these antibodies are protective against disease.24 There have been reports of transplacental transmission of SARS-CoV-2 and of symptomatic neonates who tested positive for SARS-CoV-2 after being born to mothers with positive PCR test results.25, 26, 27, 28, 29, 30 However, in these cases, the serologic status of the mother was either negative or not reported. A small case series demonstrated the presence of antibodies in RT-PCR–negative, asymptomatic neonates born to symptomatic women.31 However, the rate of transfer of maternal antibodies from the mother to the neonate and if asymptomatic women can transfer antibodies to neonates have not been established yet.32 In this paper, we aimed to systematically explore the serologic responses of mothers and neonates in both symptomatic and asymptomatic cases.

Materials and Methods

Study population

A total of 88 pregnant women who tested positive for SARS-CoV-2–specific antibodies (serology positive) at a single institution in New York City were included in this study. Of the 88 women, 67 delivered between April 18, 2020, and May 31, 2020, and were identified to be serology positive using universal serology testing. An additional 21 of the 88 women were identified to be serology positive between March 22, 2020, and April 17, 2020, after undergoing testing because of a suspicion of SARS-CoV-2 infection or exposure. The neonates born to these mothers were also included in this study and underwent serology testing using umbilical cord blood.

Laboratory testing

Patients were tested for IgM and IgG antibodies against SARS-CoV-2 using the serum or plasma from peripheral blood (for the mothers) or the plasma from umbilical cord blood (for the neonates) using the clinical testing Pylon 3D platform (ET HealthCare, Palo Alto, CA). The Pylon 3D platform utilizes a fluorescence-based reporting system that allows for the semiquantitative detection of anti–SARS-CoV-2 IgG and IgM with a specificity of 98.8% and 99.4%, respectively.8 The antibody levels were expressed as log2 (value) + 1.

Statistical analyses

To study the association between the symptoms and the serologic results, retrospective chart review was conducted to identify symptoms at the time of serology testing. Patients with any of the following COVID-19 symptoms, reported before or at the time of admission, were categorized as symptomatic: self-reported fever, cough, sore throat, rhinorrhea, shortness of breath, diarrhea, other gastrointestinal symptoms, myalgias, and loss of sense of taste or smell;4 , 24 those without any of the listed symptoms were categorized as asymptomatic. The IgM and IgG values of symptomatic and asymptomatic patients were plotted as continuous variables and were expressed as the median (interquartile range) with error bars representing 95% confidence intervals. The serology antibody levels between the symptomatic and asymptomatic patients were compared using a Welch 2 sample t test. A P value of <.05 was considered statistically significant.

To study the time course of the antibody response at the cohort level, retrospective chart review was conducted to identify the dates of onset of the first COVID-19 symptoms. Of the 88 serology positive pregnant women, 34 had documentation of the specific dates of the onset of COVID-19 symptoms. The IgM and IgG antibody levels were correlated to the number of days elapsed from the date of COVID-19 symptom onset using local polynomial regression smoothing on log2-scaled serologic values.

We studied the relationship between the quantitative maternal and neonatal IgG levels using Pearson correlation and linear regression. To understand if the maternal antibody levels were different between the pregnant women who gave birth to serology positive neonates and those who gave birth to serology negative neonates, the maternal antibody levels were compared between those who delivered serology positive vs serology negative neonates using a Welch 2 sample t test.

Retrospective chart review identified 5 women who required oxygen support (3 women needed a nasal cannula and 2 women needed a nonrebreather) during their hospital course, which likely served as a marker of disease severity. A multiple linear regression analysis was conducted to predict neonatal IgG levels from maternal symptoms (present or absent), maternal IgG level, maternal IgM level, and maternal use of oxygen support.

Statistical analyses were performed using R (version 3.6.1 R Core Team, Austria), RStudio (version 1.1.463, RStudio Team, Boston, MA), and SPSS Statistics (version 1.0.0.1461, IBM Corp, Armonk, NY).

This study was approved by the institutional review board protocols 20-03021682 and 20-04021792. A waiver of consent was granted by the institutional review board.

Results

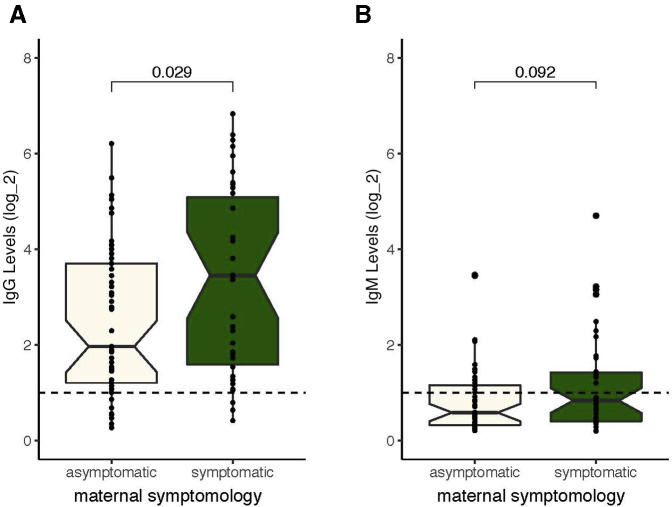

We identified 88 pregnant women who tested positive for SARS-CoV-2 IgM or IgG antibodies (10 women were IgM positive, 24 were IgM and IgG positive, and 54 women were IgG positive). A retrospective chart analysis of all 88 serology positive mothers showed that 42.0% (37/88) were symptomatic, whereas 58.0% (51/88) of serology positive patients were asymptomatic (Figure 1 ). Both asymptomatic and symptomatic pregnant women mounted a detectable IgM (Figure 1, B) and IgG (Figure 1, A) response, however, the IgG levels were significantly higher in symptomatic mothers than in asymptomatic mothers (P=.029) (Figure 1, A).

Figure 1.

IgG and IgM levels in symptomatic and asymptomatic pregnant women

A comparison of the level of (A) IgG and (B) IgM serology values in asymptomatic (beige, n=51) and symptomatic (green, n=37) pregnant women. All the positive serology cutoffs were 1 (dashed line). The values are shown on a log2 scale.

IgG, immunoglobulin G; IgM, immunoglobulin M.

Kubiak et al. Severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 serology levels in pregnant women and their neonates. Am J Obstet Gynecol 2021.

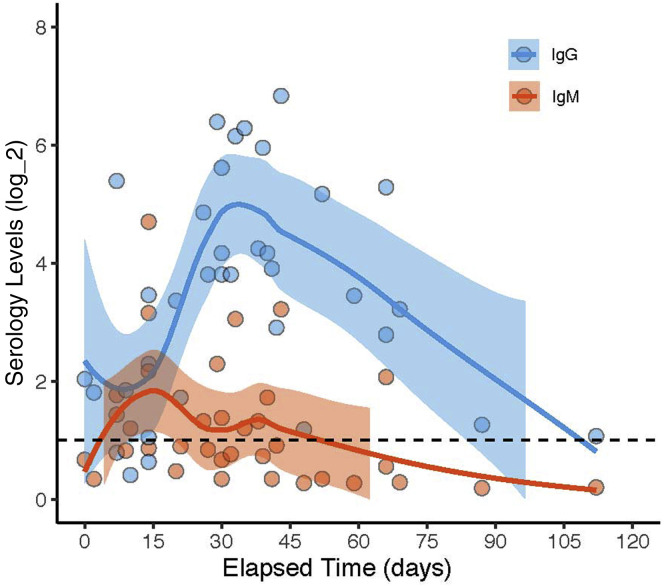

Of the 88 serology positive pregnant women, 34 women had documentation of the specific dates of the onset of first COVID-19 symptoms. Analysis of the relationship between the elapsed time from the date of symptom onset and the antibody levels for these 34 data points demonstrated that the IgM levels peaked around 15 days after symptom onset at the cohort level, whereas the IgG levels started to peak around 30 days after symptom onset and could last for more than 90 days (Figure 2 ).

Figure 2.

Timing of the serologic response in pregnant women

The serologic results were plotted as a function of time to better understand the timing of antibody response. A, IgG (blue) and IgM (red) values for each pregnant woman plotted as a function of elapsed time from the first COVID-19 symptoms. All positive serology cutoffs were 1 (dashed line). The values are shown on a log2 scale. Data are plotted as LOESS curves for each group. The shaded regions indicate the 95% confidence intervals derived during LOESS.

IgG, immunoglobulin G; IgM, immunoglobulin M; LOESS, local polynomial regression smoothing.

Kubiak et al. Severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 serology levels in pregnant women and their neonates. Am J Obstet Gynecol 2021.

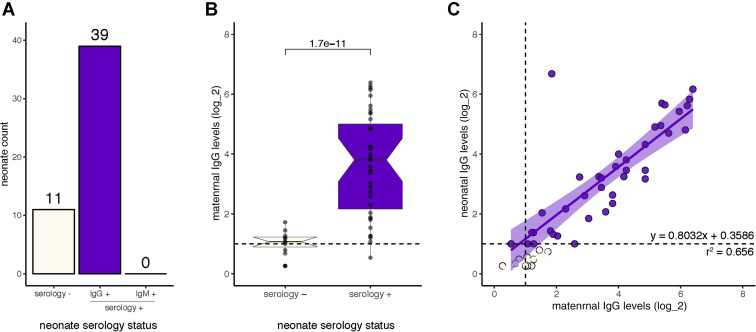

To better understand passive immunity, we analyzed 50 neonates born to a subset of our cohort of 88 pregnant women with positive serologic results. Of the 50 neonates, 78% (39/50) had positive serologic findings (with 14 being born to IgM and IgG positive mothers, 24 to IgG positive mothers, and 1 who was right at the limit of detection for both IgM and IgG was born to an IgM positive mother). All 39 neonates only had IgG antibodies and none of the neonates had IgM (Figure 3 , A). RT-PCR analysis of the 39 serology positive neonates showed that 29 of the 39 neonates (74%) were RT-PCR negative, but 10 of the 39 neonates were not tested because of a lack of sample capture. To study the factors that dictate passive immunity via SARS-CoV-2 antibodies, we analyzed the IgG levels of these mothers and neonates. Neonates with SARS-CoV-2–specific IgG antibodies were born to mothers with significantly higher IgG levels than neonates without IgG antibodies (P=1.7e-11) (Figure 3, B); and of the 39 serology positive neonates, we found that the IgG levels were positively correlated to the maternal IgG levels (Figure 3, C). A multiple linear regression analysis was conducted to show that the maternal IgG levels (P<.0005) and oxygen supplementation in a limited number of patients (P=.001) were predictive of the neonatal IgG levels. However, the maternal IgM levels and maternal symptoms were not predictive of neonatal IgG levels (P=.290 and P=.506, respectively). Model statistics: F(4, 45)=36.686; P<.0005; R2=0.826.

Figure 3.

Passive immunity and the serology levels in neonates

Neonates were tested for serology to understand the rate of passive immunity and the pattern of passive immunity between the mother to child. A, The number of neonates that were serology negative (beige) vs IgG positive (purple) neonates. No neonates were IgM positive. B, The maternal IgG antibody levels grouped by those mothers who gave birth to serology positive neonates (purple, n=39) and those who gave birth to serology negative neonates (beige, n=11). C, The IgG levels of mothers vs IgG levels of neonates. All positive serology cutoffs were 1 (dashed line). Values are shown on a log2 scale.

IgG, immunoglobulin G; IgM, immunoglobulin M.

Kubiak et al. Severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 serology levels in pregnant women and their neonates. Am J Obstet Gynecol 2021.

Comment

Principal findings

The IgG antibody response in symptomatic pregnant women was significantly higher than that of asymptomatic pregnant women. In pregnant women, the IgM and IgG levels peaked at 15 days and 30 days after COVID-19 symptom onset, respectively. Passive immunity in the form of IgG was demonstrated in 78% of the neonates, and the serology levels in mothers correlated with the serology levels of the matched neonates. The serology levels in mothers and oxygen supplementation in a limited number of mothers predicted the serology levels of the matched neonates.

Results

This study provides semiquantitative and separate IgM and IgG data for a cohort of 88 pregnant women and 50 of their neonates. The timing of the IgM and IgG response among pregnant women mirrors the timing seen in the general population and the expected classical pattern of IgM and IgG antibody response to infections.15, 16, 17 , 33 Asymptomatic women mount an immune response, albeit weaker than symptomatic women, which is consistent with similar findings in nonpregnant individuals.9 Passive immunity has been demonstrated in small cohorts or case studies, but our semiquantitative study on a large mother-baby dyad cohort demonstrated that there is a correlation between the maternal antibody levels and the amount of IgG detected in the neonatal umbilical cord blood. Furthermore, we demonstrated that maternal IgG levels and maternal oxygen supplementation—a marker of disease severity—predicted the neonatal IgG levels.

Clinical implications

We found that both symptomatic and asymptomatic women mounted a detectable antibody response; however, symptomatic women mounted a higher IgG response. Because asymptomatic, nonpregnant patients are more likely to convert to serology negative in the convalescent phase of the infection,19 and because a large cohort of the pregnant women are also asymptomatic, these data hint to a potential faster conversion to serology negative in many pregnant women, implying that even women with documented infections could be antibody negative by the time of birth, particularly if they were infected early during their pregnancies. Whether the antibodies are protective, and if so, at what levels these antibodies are correlated with protection, and how long that protection lasts are critical areas that need to be investigated next.

We demonstrated that the timeline of antibody response in pregnant women is similar to that of the nonpregnant patient population and does not deviate from the classical patterns of IgM and IgG responses.15, 16, 17 , 33 Given the difficulty to enroll pregnant women in vaccination studies, these data that confirm the classical patterns of IgM and IgG responses in SARS-CoV-2 infection, may support the reference to frameworks established in previous maternal vaccination protocols.

This study strongly suggests that maternal SARS-CoV-2–specific IgG antibodies are transferred to the neonate, particularly when the mother has a high IgG level. This implies that maternal SARS-CoV-2 infections stimulate the production of IgG antibodies, which readily cross the placenta, consistent with other maternal infections. These data suggest that if the mother mounts an antibody response secondary to a vaccination against SARS-CoV-2, those antibodies could also cross the placenta into the neonate, potentially protecting both the mother and her neonate from future infection. It is not known how protective the maternally derived IgG antibodies are for the neonate and how long the protection lasts.

Research implications

Using the methodologies described here, a larger cohort of mothers could be tested and serial studies on the same cohort could be conducted to understand the timeline of antibody production and clearance. Follow-up studies with the neonates could be conducted to study whether the maternal antibodies provide protection and would allow a better understanding of the clearance curve of the antibodies following birth. These studies will ultimately inform the scientific community about the potential benefit of maternal vaccination against SARS-CoV-2 infection when it becomes available.

Strengths and limitations

Our study has multiple strengths. Our cohort is large with consistent clinical data available. In addition, we utilized a semiquantitative, independent analysis of both IgM and IgG levels in mothers and their matched neonates. A limitation is that we did not have data on all the neonates born to our serology positive cohort because of a lack of sample capture given that this was not a prospective collection study.

The inclusion of serology positive women from both the use of universal serology testing and testing because of a suspicion for COVID-19 infection may contribute to sampling bias by sampling more severe patients; however, analysis done only on the cohort of patients identified using universal serology testing also led to the same rate of symptomatic vs asymptomatic women. The findings on the serologic differences between symptomatic and asymptomatic women are limited by the fact that we only captured data about the symptoms for 34 of the women and there may be a lack of data capture or recall bias. The serologic difference may also be caused by differences in the timing of their infections. Asymptomatic women may have a lower IgG antibody level because of a more recent infection than women who were symptomatic, and thus these women may develop both higher antibody levels and symptoms over time. The data on the timing of the serologic responses from the date of symptom onset are dependent on self-reported dates of symptoms, which introduces recall bias and are more representative of the symptomatic populations. The analysis from the time of symptom onset fails to capture the delay between when a woman became infected and when she became symptomatic; however, it is difficult to ascertain the true timing of infection in a clinical study setting. Given the lack of serial sampling of each individual patient to study the time course of serologic response, we relied on the overall trend of the entire cohort of pregnant women.

The majority of our neonatal blood samples utilized umbilical cord blood, which may be at risk of maternal blood contamination; however, we believe that these findings could not be attributed to maternal blood contamination because of the following reasons: (1) these samples were utilized for neonatal blood typing without any issues or maternal blood typing confusion, (2) none of the neonates born to IgM positive mothers tested IgM positive as would be expected if contamination did occur, and (3) peripheral blood samples available for some of the neonates served as confirmation that the presence of IgG was not because of maternal blood contamination (data not shown).

The findings on predictors of neonatal serology levels are limited by clinical data capture, and the sample size may obscure other predictors of the neonatal serology response. In addition, the data on maternal oxygen supplementation used in the multiple linear regression analysis was limited to a small number of patients, and we suspect that oxygen supplementation in the mothers is a marker of disease severity.

Conclusions

These data on the timing of the IgG and IgM response following infection and the duration of the antibody response during pregnancy may help to inform about the use of a protective vaccine for pregnant women. Our findings suggest that maternal vaccination, which stimulates the maternal IgG response, may confer protection to the neonate. Furthermore, a certain level of maternal IgG may be necessary to transfer a sufficient level of antibodies to the neonate.

Footnotes

J.M.K. and E.A.M. contributed equally to this work.

The authors report no conflict of interest.

Financial support for the research was from the Weill Cornell Medicine, New York-Presbyterian Hospital, New York, NY. The sponsors had no role in the design of this study, collection, analysis, and interpretation of data, writing of the manuscript, or the decision to submit this manuscript.

Cite this article as: Kubiak JM, Murphy EA, Yee J, et al. Severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 serology levels in pregnant women and their neonates. Am J Obstet Gynecol 2021;225:73.e1-7.

Supplementary Data

Short video

Kubiak et al. Severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 antibody in mothers and neonates. Am J Obstet Gynecol 2021.

Long video

Kubiak et al. Severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 antibody in mothers and neonates. Am J Obstet Gynecol 2021.

References

- 1.Sutton D., Fuchs K., D’Alton M., Goffman D. Universal screening for SARS-CoV-2 in women admitted for delivery. N Engl J Med. 2020;382:2163–2164. doi: 10.1056/NEJMc2009316. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Campbell K.H., Tornatore J.M., Lawrence K.E., et al. Prevalence of SARS-CoV-2 Among patients admitted for childbirth in Southern Connecticut. JAMA. 2020;323:2520–2522. doi: 10.1001/jama.2020.8904. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Zambrano L.D., Ellington S., Strid P., et al. Update: characteristics of symptomatic women of reproductive age with laboratory-confirmed SARS-CoV-2 infection by pregnancy status - United States, January 22-October 3, 2020. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2020;69:1641–1647. doi: 10.15585/mmwr.mm6944e3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Prabhu M., Cagino K., Matthews K.C., et al. Pregnancy and postpartum outcomes in a universally tested population for SARS-CoV-2 in New York City: a prospective cohort study. BJOG. 2020;127:1548–1556. doi: 10.1111/1471-0528.16403. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.DeBolt C.A., Bianco A., Limaye M.A., et al. Pregnant women with severe or critical coronavirus disease 2019 have increased composite morbidity compared with nonpregnant matched controls. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2020 doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2020.11.022. [Epub ahead of print] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Pirjani R., Hosseini R., Soori T., et al. Maternal and neonatal outcomes in COVID-19 infected pregnancies: a prospective cohort study. J Travel Med. 2020;27:taaa158. doi: 10.1093/jtm/taaa158. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Marín Gabriel M.A., Reyne Vergeli M., Caserío Carbonero S., et al. Maternal, perinatal and neonatal outcomes with COVID-19: a multicenter study of 242 pregnancies and their 248 infant newborns during their first month of life. Pediatr Infect Dis J. 2020;39:e393–e397. doi: 10.1097/INF.0000000000002902. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Antoun L., Taweel N.E., Ahmed I., Patni S., Honest H. Maternal COVID-19 infection, clinical characteristics, pregnancy, and neonatal outcome: a prospective cohort study. Eur J Obstet Gynecol Reprod Biol. 2020;252:559–562. doi: 10.1016/j.ejogrb.2020.07.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Allotey J., Stallings E., Bonet M., et al. Clinical manifestations, risk factors, and maternal and perinatal outcomes of coronavirus disease 2019 in pregnancy: living systematic review and meta-analysis. BMJ. 2020;370:m3320. doi: 10.1136/bmj.m3320. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Di Toro F., Gjoka M., Di Lorenzo G., et al. Impact of COVID-19 on maternal and neonatal outcomes: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Clin Microbiol Infect. 2021;27:36–46. doi: 10.1016/j.cmi.2020.10.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ellington S., Strid P., Tong V.T., et al. Characteristics of women of reproductive age with laboratory-confirmed SARS-CoV-2 infection by pregnancy status. United States, January 22-June 7, 2020. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2020;69:769–775. doi: 10.15585/mmwr.mm6925a1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Zullo F., Di Mascio D., Saccone G. Coronavirus disease 2019 antibody testing in pregnancy. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2020;2:100142. doi: 10.1016/j.ajogmf.2020.100142. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Peeling R.W., Wedderburn C.J., Garcia P.J., et al. Serology testing in the COVID-19 pandemic response. Lancet Infect Dis. 2020;20:e245–e249. doi: 10.1016/S1473-3099(20)30517-X. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Villalaín C., Herraiz I., Luczkowiak J., et al. Seroprevalence analysis of SARS-CoV-2 in pregnant women along the first pandemic outbreak and perinatal outcome. PLoS One. 2020;15 doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0243029. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Yang H.S., Racine-Brzostek S.E., Lee W.T., et al. SARS-CoV-2 antibody characterization in emergency department, hospitalized and convalescent patients by two semi-quantitative immunoassays. Clin Chim Act. 2020;509:117–125. doi: 10.1016/j.cca.2020.06.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Long Q.X., Liu B.Z., Deng H.J., et al. Antibody responses to SARS-CoV-2 in patients with COVID-19. Nat Med. 2020;26:845–848. doi: 10.1038/s41591-020-0897-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.To K.K.W., Tsang O.T.Y., Leung W.S., et al. Temporal profiles of viral load in posterior oropharyngeal saliva samples and serum antibody responses during infection by SARS-CoV-2: an observational cohort study. Lancet Infect Dis. 2020;20:565–574. doi: 10.1016/S1473-3099(20)30196-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Zhang B., Zhou X., Zhu C., et al. Immune phenotyping based on the neutrophil-to-lymphocyte ratio and IgG level predicts disease severity and outcome for patients with COVID-19. Front Mol Biosci. 2020;7:157. doi: 10.3389/fmolb.2020.00157. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Long Q.X., Tang X.J., Shi Q.L., et al. Clinical and immunological assessment of asymptomatic SARS-CoV-2 infections. Nat Med. 2020;26:1200–1204. doi: 10.1038/s41591-020-0965-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Winter A.K., Hegde S.T. The important role of serology for COVID-19 control. Lancet Infect Dis. 2020;20:758–759. doi: 10.1016/S1473-3099(20)30322-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Mor G., Cardenas I. The immune system in pregnancy: a Unique Complexity. Am J Reprod Immunol. 2011;63:425–433. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0897.2010.00836.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Crovetto F., Crispi F., Llurba E., Figueras F., Gómez-Roig M.D., Gratacós E. Seroprevalence and presentation of SARS-CoV-2 in pregnancy. Lancet. 2020;396:530–531. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(20)31714-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Flannery D.D., Gouma S., Dhudasia M.B., et al. SARS-CoV-2 seroprevalence among parturient women in Philadelphia. Sci Immunol. 2020;5 doi: 10.1126/sciimmunol.abd5709. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Pettirosso E., Giles M., Cole S., Rees M. COVID-19 and pregnancy: a review of clinical characteristics, obstetric outcomes and vertical transmission. Aust N Z J Obstet Gynaecol. 2020;60:640–659. doi: 10.1111/ajo.13204. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Vivanti A.J., Vauloup-Fellous C., Prevot S., et al. Transplacental transmission of SARS-CoV-2 infection. Nat Commun. 2020;11:3572. doi: 10.1038/s41467-020-17436-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Alzamora M.C., Paredes T., Caceres D., Webb C.M., Valdez L.M., La Rosa M. Severe COVID-19 during pregnancy and possible vertical transmission. Am J Perinatol. 2020;37:861–865. doi: 10.1055/s-0040-1710050. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Dong L., Tian J., He S., et al. Possible vertical transmission of SARS-CoV-2 from an infected mother to her newborn. JAMA. 2020;323:1846–1848. doi: 10.1001/jama.2020.4621. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Zeng L., Xia S., Yuan W., et al. Neonatal early-onset infection with SARS-CoV-2 in 33 neonates born to mothers with COVID-19 in Wuhan, China. JAMA Pediatr. 2020;174:722–725. doi: 10.1001/jamapediatrics.2020.0878. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Lamouroux A., Attie-Bitach T., Martinovic J., Leruez-Ville M., Ville Y. Evidence for and against vertical transmission for severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2020;223:91.e1–91.e4. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2020.04.039. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Shah P.S., Diambomba Y., Acharya G., Morris S.K., Bitnun A. Classification system and case definition for SARS-CoV-2 infection in pregnant women, fetuses, and neonates. Acta Obstet Gynecol Scand. 2020;99:565–568. doi: 10.1111/aogs.13870. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Zeng H., Xu C., Fan J., et al. Antibodies in infants born to mothers with COVID-19 pneumonia. JAMA. 2020;323:1848–1849. doi: 10.1001/jama.2020.4861. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Toner L.E., Gelber S.E., Pena J.A., Fox N.S., Rebarber A. A case report to assess passive immunity in a COVID positive pregnant patient. Am J Perinatol. 2020;37:1280–1282. doi: 10.1055/s-0040-1715643. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Sethuraman N., Jeremiah S.S., Ryo A. Interpreting diagnostic tests for SARS-CoV-2. JAMA. 2020;323:2249–2251. doi: 10.1001/jama.2020.8259. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Short video

Kubiak et al. Severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 antibody in mothers and neonates. Am J Obstet Gynecol 2021.

Long video

Kubiak et al. Severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 antibody in mothers and neonates. Am J Obstet Gynecol 2021.