Abstract

The diagnosis of indolent systemic mastocytosis can be quite a challenge due to its wide spectrum of clinical manifestations. We are reporting a case of misdiagnosed indolent systemic mastocytosis in a 41-year-old male that has been wrongly treated first as a Non-Hodgkin lymphoma. The patient had generalized lymphadenopathy and eosinophilia, which are rare manifestations of indolent systemic mastocytosis. The chronic neglected pruritus and elevated tryptase levels along with histological findings were the main clues that have led us to the final diagnosis of indolent systemic mastocytosis. Later during the coronavirus disease 2019 pandemic, the patient presented with symptoms that are common between coronavirus disease 2019 and mast cell activation syndrome. Coronavirus disease 2019 was confirmed with a polymerase chain reaction test. There were no clear guidelines for managing a case like ours, so our management plan was based on the latest recommendations published at that time.

Keywords: COVID-19, COVID-19 pandemic, Eosinophilia, Generalized lymphadenopathy, Indolent mastocytosis, Mast cell activation syndrome

Highlights

-

•

The difficulty of diagnosing indolent systemic mastocytosis comes from its exceptional diversity.

-

•

Little is known about management indolent systemic mastocytosis and coronavirus disease 2019.

-

•

Definitive evidence is lacking whether mast cells play a defending or accelerating role in coronavirus disease 2019.

1. Introduction

Systemic mastocytosis (SM) is a rare disorder; it affects about one in 500,000 people mainly in the developed countries [1]. Indolent systemic mastocytosis (ISM) is usually a benign form of SM characterized by an abnormal accumulation of neoplastic mast cells (MCs) [2]. ISM can manifest in a myriad of symptoms ranging from frequently inconvenient to possibly fatal, and is often confused with other internal disorders, which leads to delay in the diagnosis up to 10 years [3]. It is questionable whether patients with mastocytosis have an increased risk to acquire severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2) infection and/or an increased risk to develop a more severe course of coronavirus Disease 19 (COVID-19). It is also debatable whether MC mediator–related symptoms are aggravated by the viral infection and how treatment of MC diseases might affect the course of COVID-19 [4]. Treatment is so far unsettled and requires expert opinions based on case experience and reports from patients since no published data are yet available [4].

2. Case presentation

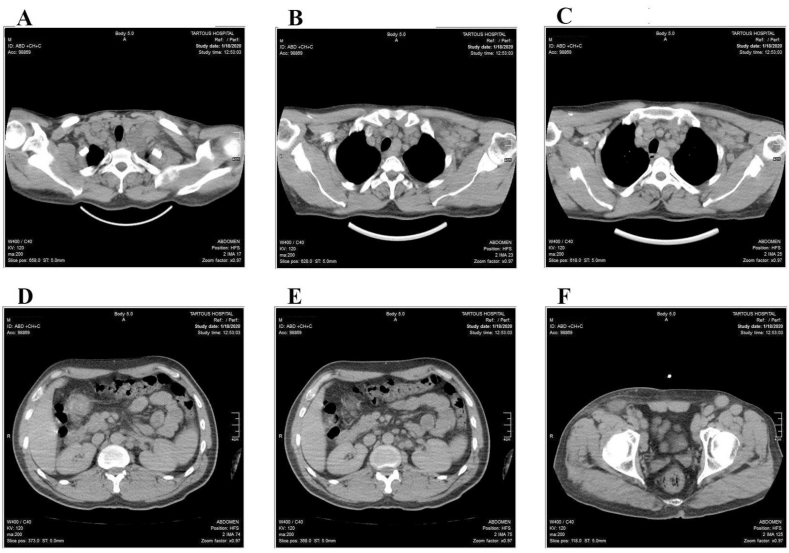

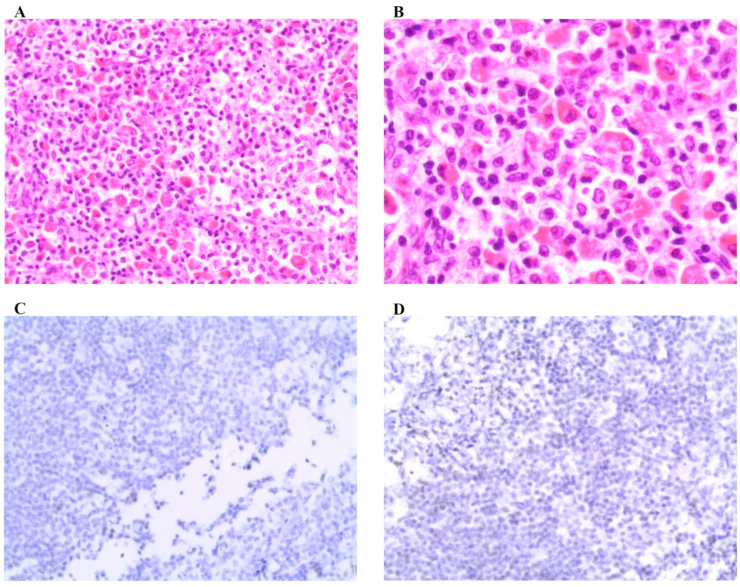

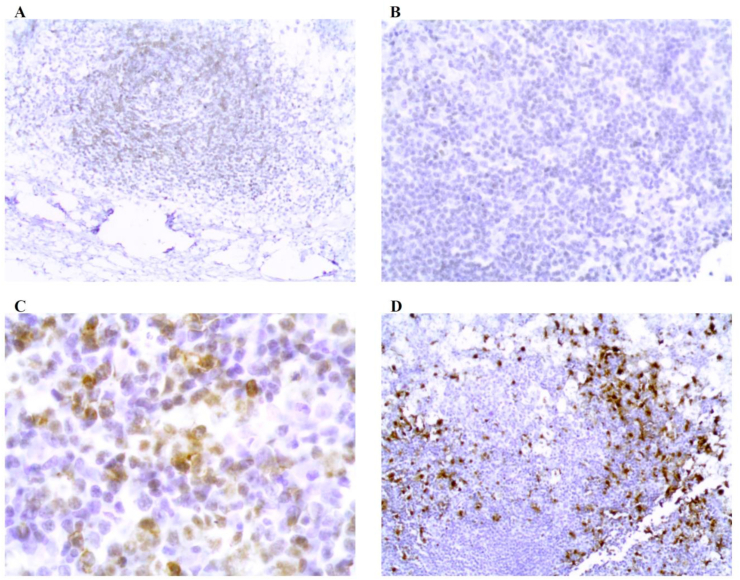

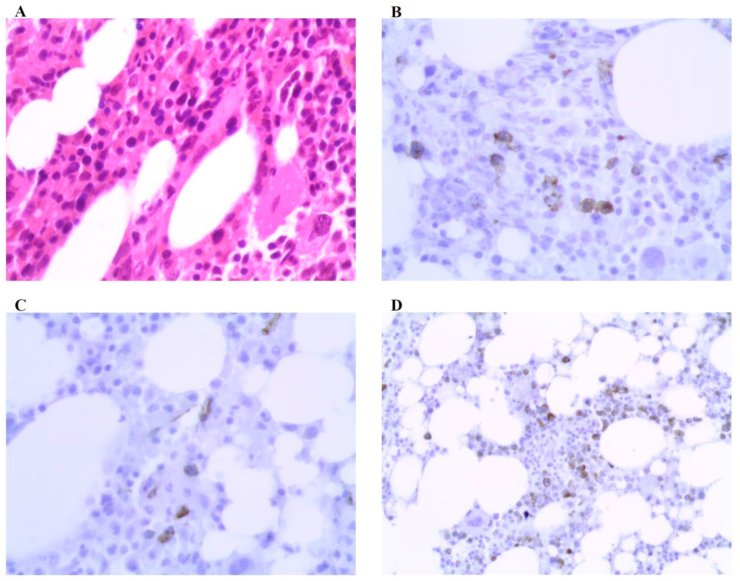

A 41-year-old male was transferred to our department from a rural hospital as a misdiagnosed Non-Hodgkin Lymphoma patient for further evaluation because he showed no noticeable improvements despite being treated with Cyclophosphamide, Vincristine and Prednisone (CVP) regimen for three months. A whole new reassessment was made. On history taking, we only found that he has been suffering from severely neglected pruritus for the past two years along with episodes of diarrhea accompanied by abdominal pain. The physical examination revealed enlarged cervical, axillary and inguinal lymph nodes. No hepatosplenomegaly was detected. Ultrasound revealed enlarged lymph nodes (up to 4 cm in diameter) with absence of their normal cortico-medullary differentiation and central resonance. The patient underwent a Computerized Tomography (CT) scan that showed generalized lymphadenopathy (Fig. 1). Admission workup was within normal except for mild cytopenia and eosinophilia (12%) (0.79 10 × 3/UL). In light of elevated eosinophilia and the neglected complaint of severe chronic pruritus along with the generalized lymphadenopathy found on CT scan, we suspected the presence of a mast cell disease. Thus, we performed a serum tryptase test; it turned out to be elevated 73 ng/ml (normal< 11.4 ng/ml). Therefore, biopsies of right inguinal lymph node and bone marrow were pursued to confirm our diagnosis. The inguinal lymph node biopsy revealed vascular proliferation, mast cells’ infiltration with accompanying eosinophilia, and variable fibrosis (Fig. 2, Fig. 3). Additionally, the bone marrow biopsy revealed 40–50% of bone marrow cellularity with a significant increase in mast cells (Fig. 4). Depending on the histological findings, the clinical symptoms and elevated serum tryptase, the patient met the criteria for the diagnosis of systemic mastocytosis (SM) [Table 1]. The immune staining panel (CD117, CD34, and MPO) of both biopsies supported the diagnosis of indolent systemic mastocytosis (ISM) type (Fig. 3, Fig. 4). The patient was treated with an antihistamine, cromolyn sodium, vitamin D and glucocorticoids and was advised to carry an epinephrine self-injector for emergencies, avoid the known symptom triggers and maintain regular follow-ups. On his first follow-up, there was a remarkable improvement of the symptoms with declined serum tryptase levels (went down to 20 ng/ml). Later during the pandemic of (COVID-19), the patient presented with sudden deterioration (severe generalized pruritus, urticaria, flushing, fever, and cough) despite taking an epinephrine self-injection. A chest x-ray (CXR) revealed peripheral ground-glass opacities (GGO) that affected the lower lobes, which is associated with COVID-19 in this pandemic period. COVID-19 was confirmed using PCR test, so the patient was treated according to COVID-19 treatment protocol used at our hospital (supportive care and remdesivir as an anti-viral drug), and his previous medical regimen was resumed with the exception of replacing glucocorticoids with omalizumab according to the recently published guideline for ISM patients infected by COVID-19. On the next follow-up (two weeks later) the patient showed a stability in ISM and improved COVID-19 symptoms.

Fig. 1.

Body CT scan that revealed multiple groups of enlarged lymph nodes: (A)bilateral cervical (3 cm in max diameter)and bilateral supraclavicular. (B&C)mediastinal and bilateral sub-axillary (2.5 cm in max diameter). (D&E) mild enlargement around the abdominal aorta and pelvis. (F)inguinal lymph nodes (4 cm in max diameter).

Fig. 2.

Lymph node biopsy immunohistochemical staining: (A)zoom200. (B)zoom400. (C)ALK negative. (D)CD1a negative.

Fig. 3.

Lymph node biopsy immunohistochemical staining: (A) CD45 negative. (B) CD68 negative. (C)CD117 positive. (D)S100 positive.

Fig. 4.

Bone marrow biopsy immunohistochemical staining: (A)zoom400. (B)CD117 positive. (C)CD34 positive. (D)MPO positive.

Table 1.

A diagnosis of systemic mastocytosis can be established when the major criterion and at least one minor criterion are fulfilled or when at least three minor criteria (without demonstration of the major criterion) are fulfilled.

| Mastocytosis Diagnostic Criteria | |

|---|---|

| Major Criterion* |

|

| Minor Criteria* |

|

| |

| |

| |

| B Findings |

|

| |

| |

| C Findings |

|

| |

| |

| |

| |

3. Discussion

Mastocytosis is a rare heterogeneous disorder that can occur at any age. It is characterized by expansion and accumulation of clonal mast cells (MCs) in various organ systems [2]. It is classified into two main types: cutaneous mastocytosis, which accounts for >80% of the mastocytosis cases, and systemic mastocytosis, which involves at least one extracutaneous organ [2]. ISM is by far the most frequent subtype involving mainly skin and bone marrow [5]. It is defined by SM criteria according to WHO 2017 classification of mastocytosis [6]. Due to the lack of clarity in the causes, symptoms and triggers, ISM is a disease that is extremely hard to diagnose, and accurate diagnosis may take up to 10 years [1], which justifies the delay of ISM diagnosis in our patient. Activation of MCs is responsible for most ISM symptoms [5]. The main trigger of MC degranulation is stimulation by IgE [7]. ISM symptoms are also chiefly attributed to MC degranulation and mediator release. According to Luis Escribano et al., skin lesions, which are the most frequent manifestation of ISM as they're found in 90% of patients, were absent in our patient. Other manifestations may include generalized pruritus 80%, flushing 56%, GI manifestations -such as Diarrhea 35%, abdominal cramping 30% and peptic symptoms 20%- hepatosplenomegaly 20%, osteoporosis 18%, bone fractures 3%, and Lymph node enlargement 3% [2](3). Eosinophilia, which is present in our case, is a rare laboratory finding found in 7% of cases [3]. Bone marrow is the most associated extracutaneous organ in ISM [2] with a low degree of infiltration that does not exceed 10% [2]. However, Lymph node involvement, particularly generalized lymphadenopathy, is an infrequent finding in ISM and is commonly associated with smoldering or aggressive subtypes [2]. The two novel screen parameters of ISM are the serum tryptase level, which was elevated (>20 ng\dl) in 71% of patients [3], and KIT D816V mutation which can be detected in >70% of patients [2,6]. One final crucial diagnostic feature of ISM is immunohistochemistry studies that identify MCs infiltrations in various tissues [2]. Because ISM has various symptoms, the treatment is customized for each patient; an antihistamine is used to control mediator effects [6], and corticosteroids and MCs stabilizers are used in patients with severe allergic reactions. Another important part of treatment is the avoidance of known symptom triggers [8]. Patients are also advised to carry epinephrine pen self-injectors to avoid the risk of life-threatening anaphylaxis. Although the overall prognosis of ISM patients is relatively good compared to other SM subgroups, transformation of ISM to a more aggressive form of the disease is evident in some ISM cases [2,8]. Thus, Follow-up investigations should be performed annually and must include physical examination and routine laboratory tests with serum tryptase [8]. The possible role of MCs in coronavirus infections remains uncertain; MCs are thought to have an active role in viral diseases such as COVID-19; however, they have also been suggested as possible contributors to coronavirus-mediated inflammation storm in the lungs [4]. The expert-dependent recommendations for ISM patients infected with COVID-19 are the followings [4]:

-

•

Always carry an adrenaline auto-injector.

-

•

Resume H1 and H2 antihistamines, cromolyn sodium, omalizumab, vitamin D, bisphosphonates and/or denosumab.

-

•

Stop or decrease systemic glucocorticoids if possible.

-

•

Adjust systemic glucocorticoid intake (stopping, reducing, or continuing) according to the phase of COVID-19.

-

•

Carry on hymenoptera venom immunotherapy.

-

•

Delay non-urgent medical visits for routine checkups.

4. Conclusion

To sum up, the difficulty of diagnosing indolent systemic mastocytosis comes from its exceptional diversity. Therefore, physicians must suspect indolent systemic mastocytosis upon recognizing the combination of its manifestations and confirm the diagnosis with serum tryptase test and histopathological studies. So far, little is known about managing ISM and coronavirus disease 2019, and definitive evidence is lacking whether mast cells play a defending or accelerating role in Coronavirus disease 2019.

Patient perspective

The patient participated in the treatment decision and he was satisfied with the results of the treatment after identifying the final diagnosis.

Patient consent form

Written informed consent was obtained from the patient for publication of this case report and accompanying images. A copy of the written consent is available for review by the Editor-in-Chief of this journal on request.

Provenance and peer review

Not commissioned, externally peer-reviewed.

Ethics approval

No ethical approval necessary.

Sources of funding

There are no sources of funding.

Author contribution

All authors contributed almost equally in all the phases of preparing the manuscript.

Registration of research studies

Not applicable. Our manuscript is a case report.

Guarantor

Amjad Soltany, MD.

Declaration of competing interest

We have no conflict of interest.

Acknowledgements

All thanks go to Zeinab Mohanna, an English Literature student in Tishreen University, for her linguistic revision and editing of our case and Dr. Ahmad Abo Abbad for his radiology consult.

Footnotes

Supplementary data to this article can be found online at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.amsu.2021.01.062.

Appendix A. Supplementary data

The following is the Supplementary data to this article:

References

- 1.Sev'er Aysan, Sibbald R. Gary, D'Arville Carrie. University of Toronto Press; 2009. Thousand Faces of Mastocytosis: Mistaken Medical Diagnoses, Patient Suffering & Gender Implications; pp. 84–112.http://mastocytosis.ca/MSC%20Research%20Paper%202009.pdf Available from. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Arber Daniel A., Campo Elias, Harris Nancy L. Elsevier; Philadelphia, PA: 2017. Elaine Sarkin Jaffe, and Leticia Quintanilla-Martinez. Hematopathology. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Escribano L., Alvarez-Twose I., Sánchez-Muñoz L., Garcia-Montero Andres, Rosa Núñez, Julia Almeida Prognosis in adult indolent systemic mastocytosis: a long-term study of the Spanish Network on Mastocytosis in a series of 145 patients. J. Allergy Clin. Immunol. 2009;124(3):514–521. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2009.05.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Valent P., Akin C., Bonadonna P. Risk and management of patients with mastocytosis and MCAS in the SARS-CoV-2 (COVID-19) pandemic: expert opinions. J. Allergy Clin. Immunol. 2020;146(2):300–306. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2020.06.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Desmond D.H., Carmichael M.G. Systemic mastocytosis: the difficult patient with a rare disease. Case presentation and brief review. Hawai‘i J. Med. Public Health. 2018;77(2):27–29. PMID: 29435387 PMCID: PMC5801525. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Valent P. Diagnosis and management of mastocytosis: an emerging challenge in applied hematology. Hematology Am Soc Hematol Educ Program. 2015;2015:98–105. doi: 10.1182/asheducation-2015.1.98. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Woessner S., Lafuente R., Pardo P., Rosell R., Rozman C., Sans-Sabrafen J. Systemic mastocytosis: a case report. Acta Haematol. 1977;58:321–331. doi: 10.1159/000207846. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Pardanani A. How I treat patients with indolent and smoldering mastocytosis (rare conditions but difficult to manage) Blood. 2013;121(16):3085–3094. doi: 10.1182/blood-2013-01-453183. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.