Why was the cohort set up?

Illicit drug use is associated with severe health-related harms and an elevated risk of mortality. In Canada and globally, people with substance use disorder (PWSUD) experience high rates of co-occurring mental illness, infectious disease and chronic conditions that are further exacerbated by high rates of poverty and homelessness.1,2 However, despite their complex health challenges, PWSUD face substantial barriers to care.3–6 Historically, primary care, substance use services and mental health care services have developed and operated separately in North America.7,8 As a result, PWSUD often access care from multiple sources9 and rely heavily on acute and emergency services.10–14 This kind of fragmented care delivery has been associated with poor health outcomes.2,15 Nonetheless, despite a growing recognition of the importance of integrated care for this population, significant barriers to health care integration remain.2,16,17 Improved integration across the continuum of health care services for PWSUD, including improved linkages between acute, primary and community-based services, is urgently needed.

In British Columbia (BC), Canada, a public health emergency was declared in April 2016 following a rapid increase in drug-related deaths due to contamination of the illicit drug supply with fentanyl and its analogues.18,19 In 2017, there were 1495 illicit drug overdose deaths in the province (rate 30.4 per 100 000), representing an increase of 51% from 2016 and 182% from 2015.19 The announcement prompted a coordinated and multifaceted public health response across the province, including the establishment of emergency harm reduction services,20–22 numerous policy and practice initiatives to improve treatment availability for PWSUD23–27 and a newly formed Ministry of Mental Health and Addictions to coordinate these efforts.28

Much of this response was concentrated in Vancouver’s Downtown Eastside (DTES) neighbourhood, where a large proportion of the province’s most vulnerable PWSUD reside and access health care services. The DTES has historically experienced high rates of poverty, homelessness, communicable disease and complex concurrent substance use and mental health disorders,29–31 presenting unique challenges to the delivery of health care services in the neighbourhood. Before the public health emergency declaration, Vancouver Coastal Health Authority (VCH) planned a systemic redesign of health care services in the DTES. A key focus of this redesign was to improve access to coordinated, integrated health care.32 The Downtown Eastside Second Generation Strategy (DTES-2GS) included: the establishment of a low-barrier addiction clinic providing rapid access to opioid agonist treatment (OAT); a new community health clinic for people with multiple concurrent disorders; integrated care teams within three existing community health clinics; intensive case management teams; a new drop-in centre; partnerships with private clinics to improve care coordination with public health care services; staff competency training including Indigenous cultural safety, trauma-informed care, harm reduction and pain management; and the integration of peer navigators into health care teams.32–35

Within this context, we developed the provincial cohort of PWSUD and a key subgroup DTES-2GS to monitor service use, health care integration and patient outcomes in British Columbia on a continuing basis and also, to provide the foundation for evaluative studies on the costs and benefits of the DTES-2GS. A unique and unprecedented linkage of local and provincial health administrative data sources was conducted to develop a set of quantitative indicators to achieve these evaluative aims. British Columbia operates as a single-payer health care system, offering some of the world’s most comprehensive health administrative datasets. However, provincial data sources do not capture all services specific to the DTES-2GS, which are necessary to effectively evaluate its impact on health care integration across the continuum of health care services available in the DTES. To address this limitation, we linked provincial-level data with VCH-specific data sources capturing community health care services and acute care contacts in the DTES. The resulting database offers a critical opportunity to evaluate the impact of these health system changes amid an unprecedented public health emergency. We secured funding for this cohort from the Canadian Institutes of Health Research, with additional funding support from VCH.

Who is in the cohort?

The cohort was defined based on an individual-level linkage of seven health administrative databases held by Population Data BC (provincial data holdings) and VCH data stewards. The Discharge Abstract Database (DAD),36 the Medical Services Plan (MSP) database,37 the PharmaNet database,38 the National Ambulatory Care Reporting System (NACRS)39 and the Vital Statistics database were provided to the study team by Population Data BC.40 These datasets were linked with two local VCH datasets: the EDMart database and the CommunityMart database. The datasets were deterministically linked based on unique personal health numbers used to track individual contacts with the health care system which are recorded in each database. We describe each of the component databases included in our analyses in Figure 1. We also present key features of the databases in Supplementary Table S1, available as Supplementary data at IJE online, a list of hospitals reporting to NACRS in Supplementary Table S2, available as Supplementary data at IJE online, and community-based services captured in the CommunityMart database in Supplementary Table S3, available as Supplementary data at IJE online.

Figure 1.

Data linkage and key variables of the provincial and local databases. Acronyms: BC: British Columbia, VCH: Vancouver Coast Health Authority, DTES-2GS: Downtown Eastside Second Generation Strategy, ICD-9/10-CA: International Statistical Classification of Diseases and Related Health Problems (ICD), Ninth and Tenth Revisions, Canada.

The provincial cohort includes all people with any indication of substance use disorder (SUD) in any of the linked health administrative databases between 1 April 2009 and 31 March 2017. The case-finding algorithm used to identify this population is described in Supplementary Table S4, available as Supplementary data at IJE online. Two key subgroups comprise the provincial substance use disorder cohort: the DTES-2GS cohort and non-DTES-2GS PWSUD. The DTES-2GS cohort is the subset of the provincial cohort selected based on an indication of DTES residency in the DAD or EDMart, or receiving at least one community-based service in the DTES within the study period. This cohort will primarily inform the evaluation of the DTES-2GS through the analysis of care pathways of people exposed to the DTES-2GS policy changes. Other members of the provincial SUD cohort will provide a basis of comparison to evaluate the effects of specific services and policies introduced as part of the DTES-2GS. As of 31 March 2017, there were 162 099 individuals in the provincial cohort, with 22 579 (13.9%) included in the DTES-2GS cohort (Table 1).

Table 1.

Demographic characteristics and health service use rates of cohort participants

| Characteristics, n (%) | Provincial cohort | DTES-2GS cohort | Non-DTES-2GS PWSUD |

|---|---|---|---|

| n = 162 099 (100) | n = 22 579 (13.9) | n = 139 520 (86.1) | |

| At least one hospitalization | 133 483 (82.4) | 19 589 (86.8) | 113 894 (81.6) |

| At least one emergency department visit | 111 100 (68.5) | 20 328 (90.0) | 90 772 (65.1) |

| At least one physician billing record | 160 726 (99.2) | 21 752 (96.3) | 138 974 (99.6) |

| At least one drug dispensation record | 154 253 (95.2) | 21 953 (97.2) | 132 300 (94.8) |

| Follow-up years, median (IQR) | 6.8 (3.8,7.8) | 8.0 (7.8,8.0) | 5.8 (3.8,7.8) |

| Age at cohort entry, median (IQR) | 39.8 (27.7,51.3) | 39.3 (29.0,48.3) | 39.8 (27.5,51.9) |

| Gender | |||

| Female | 64 776 (40.0) | 6764 (30.0) | 58 012 (41.6) |

| Male | 97 315 (60.0) | 15 813 (70.0) | 81 502 (58.4) |

| Unknown | 8 (0.0) | 2 (0.0) | 6 (0.0) |

| Ever lived in Downtown Eastsidea | 21 070 (13.0) | 17 420 (77.2) | 3650 (2.6) |

| Homeless, everb | 13 154 (8.1) | 7641 (33.8) | 5513 (4.0) |

| Receiving any income assistance, everc | 85 991 (53.1) | 19 471 (86.2) | 66 520 (47.7) |

| Fiscal year of cohort entry | |||

| 2009 | 153 102 (94.5) | 21 077 (93.3) | 132 025 (94.6) |

| 2010–12 | 4191 (2.6) | 750 (3.3) | 3441 (2.5) |

| 2013–15 | 3165 (2.0) | 605 (2.7) | 2560 (1.8) |

| 2016–17 | 1641 (1.0) | 147 (0.7) | 1494 (1.1) |

| Health care service use rate per person-year, median (IQR) | |||

| Physician visit rate | 20.5 (9.8, 38.6) | 17.4 (7.8, 35.7) | 20.9 (10.2, 39.0) |

| Drug dispensation days | 619.7 (147.6, 1760.8) | 575.5 (167.7, 1461.3) | 629.1 (143.9, 1815.5) |

| ER visit rate and total numbersd | 0.6 (0.0,1.7) | 1.0 (0.4,2.3) | 0.4 (0.0,1.7) |

| 0 | 50 999 (31.5) | 2251 (10.0) | 48 748 (34.9) |

| 1 | 20 945 (12.9) | 1855 (8.2) | 19 090 (13.7) |

| 2–5 | 44 493 (27.5) | 5970 (26.4) | 38 523 (27.6) |

| 6+ | 45 662 (28.2) | 12 503 (55.4) | 33 159 (23.8) |

| Hospitalization rate and total numbers | 0.7 (0.3,1.6) | 0.5 (0.1,1.0) | 0.8 (0.3,1.7) |

| 0 | 28 616 (17.7) | 2990 (13.2) | 25 626 (18.4) |

| 1 | 15 636 (9.7) | 3549 (15.7) | 12 087 (8.7) |

| 2–5 | 56 248 (34.7) | 8740 (38.7) | 47 508 (34.1) |

| 6+ | 61 599 (38.0) | 7300 (32.3) | 54 299 (38.9) |

| Died as of 31 March 2017 | 18 093 (11.2) | 2548 (11.3) | 15 545 (11.1) |

| Administrative loss to follow-upe | 10 569 (6.5) | 243 (1.1) | 10 326 (7.4) |

DTES, Downtown Eastside; DTES-2GS, Downtown Eastside Second Generation Strategy; PWSUD, people with substance use disorder; IQR: inter-quartile range; ER: emergency room; ICD-9/10-CA, International Statistical Classification of Diseases and Related Health Problems (ICD), Ninth and Tenth Revisions, Canada.

Individuals having DTES indication, determined by known residential postal code, or homeless user of DTES-2GS services in at least one health care record during follow-up.

Determined by ICD-9-CA code V60.0, V60.1 or ICD-10-CA code Z59.0, Z59.1 in at least one health care record during follow-up, or homeless user of DTES-2GS services.

At least one PharmaNet record of enrolment in Pharmacare Plan C during follow-up.

DTES-2GS cohort: emergency department admission was available from 1 April 2009 onwards. Control group: emergency department admission was available from 1 April 2012 onwards.

No health care record 66 months preceding end of study follow-up date 31 March 2017.

Cohort characteristics

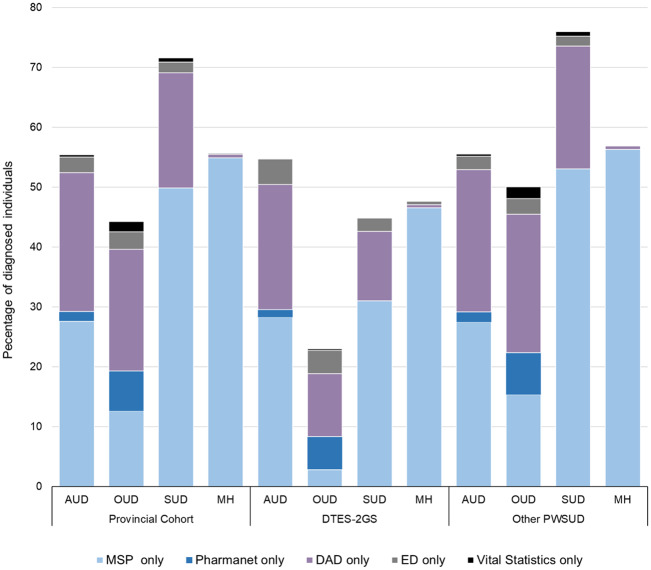

Table 1 provides demographic and health service use characteristics and Table 2 provides health conditions of each of the three cohort subgroups. The provincial cohort was predominantly male (60.0%), with a median age of 39.9 [interquartile range (IQR): 27.7, 51.3] years at the first health service use record. Just over half (53.1%) of the cohort had a history of receiving income assistance and 8.1% were homeless at least once during the study period. The majority (68.5%) of the provincial cohort had at least one emergency department (ED) visit, 82.4% had at least one hospitalization and nearly everyone had at least one physician billing and drug dispensation record (99.2% and 95.2%, respectively). We identified 57 176 (35.3%) individuals with opioid use disorder (OUD), 151 325 (93.4%) individuals with non-opioid SUD and 138 990 (85.7%) individuals with a mental health condition. Physician billing records exclusively captured approximately half of all non-opioid SUD (49.9%) and mental health conditions (55.0%) and a small number (12.6%) of OUD. A further 21.0% of non-opioid SUD were identified only in acute care (Figure 2).

Table 2.

Identification of substance use disorders and mental health conditions among cohort participants

| Number of individuals (%)a |

|||

|---|---|---|---|

| Health conditions | Provincial cohort | DTES-2GS cohort | Non-DTES-2GS PWSUD |

| n = 162 099 | n = 22 579 | n = 139 520 | |

| Alcohol use disorders | 60 327 (37.2) | 11 396 (50.5) | 48 931 (35.1) |

| Opioid use disorder | 57 176 (35.3) | 12 515 (55.4) | 44 661 (32.0) |

| Other substance use disordersb | 151 323 (93.4) | 21 649 (95.9) | 129 674 (92.9) |

| Any mental health conditions | 138 990 (85.7) | 19 943 (88.3) | 119 047 (85.3) |

| Anxiety disorder | 113 186 (69.8) | 16 241 (71.9) | 96 945 (69.5) |

| Depression | 117 786 (72.7) | 16 745 (74.2) | 101 041 (72.4) |

| Bipolar disorder | 49 471 (30.5) | 8165 (36.2) | 41 306 (29.6) |

| Schizophrenia or other psychoses | 31 317 (19.3) | 7373 (32.7) | 23 944 (17.2) |

| Stress and adjustment disorder | 63 775 (39.3) | 10 254 (45.4) | 53 521 (38.4) |

| Personality disorders | 25 996 (16.0) | 5261 (23.3) | 20 735 (14.9) |

| Development disorder | 1790 (1.1) | 450 (2.0) | 1340 (1.0) |

| Attention deficiency | 9749 (6.0) | 1576 (7.0) | 8173 (5.9) |

DTES-2GS, Downtown Eastside Second Generation Strategy; PWSUD, people with substance use disorder.

Numerator: number of diagnosed individuals; denominator: number of cohort participants.

Non-opioid or non-alcohol substance use disorder.

Figure 2.

Identification of substance use disorders and mental health conditions. Acronyms: AUD: alcohol use disorder; OUD: opioid use disorder; SUD: non-opioid, non-alcohol substance use disorder; MH: mental health, PWSUD: people with substance use disorder; MSP: Medical Services Plan; DAD: District Abstract Database; ED: Emergency Department.

Compared with non-DTES-2GS PWSUD, a higher percentage of DTES-2GS cohort participants were homeless (33.8% vs 4.0%) and received income assistance (86.2% vs. 47.7%) (Table 1). At the end of follow-up, more DTES-2GS cohort members visited the ED (90.0% vs 65.1%) and were hospitalized (86.8% vs 81.6%) compared with non-DTES-2GS PWSUD. In the DTES-2GS cohort, we identified 21 649 (96.0%) people with non-opioid SUD, 12 515 (55.5%) people with opioid use disorder (PWOUD) and 19 943 (88.3%) people with a mental health condition (Table 2).

How often have they been followed up?

This cohort captures health care use longitudinally. Data capture in the initial extract ran from 1 April 2009 to 31 March 2017. Since follow-up depends on health system contacts, individuals are lost to follow-up if they move out of British Columbia or die. Individuals with no death record at end of the study period, and no records in the health administrative databases between 1 September 2011 and 31 March 2017, were classified as lost to follow-up. This 66-month cut-off period was determined empirically based on the 97.5th percentile in gap times between points of contact with health care services captured in our database. The detailed information regarding the determination of the cut-off period is described elsewhere.41 The median duration of follow-up of the provincial cohort was 6.8 (IQR: 3.8, 7.8) years from first health care service contact until the end of study follow-up or death; 11.2% of the cohort died during follow-up and another 6.5% were lost to follow-up; 2.2% of the individuals who were lost to follow-up and 14.1% of the individuals who died were in the DTES-2GS cohort. Of the total 133 437 individuals alive and not administratively censored at the end of the study period, 14.8% were in the DTES-2GS cohort. The cohort will be updated annually as new data become available.

What has been measured?

Patient demographics

We obtained information on individuals’ demographic characteristics including age, gender, location, DTES residency, receipt of income assistance, homelessness status at the time of service use, and death through the provincial vital statistics database.

Health care services data

The DAD contains information on all admitted patient services at all hospitals.42 For acute care, the resource intensity weight, comorbidity code, Major Clinical Category code43 and the Case Mix Group Plus code43,44 enable researchers to estimate daily costs per hospital stay. The PharmaNet database includes information on cost of medications dispensed by the pharmacies in the province; it provides a unique opportunity to estimate the province-wide spending on prescription medications for SUD and co-existing conditions. Finally, the CommunityMart database documents individual contacts with community-based services within VCH. Similar data are not available for other regions of the province.

Health care integration and monitoring

Together, these datasets allow for a robust examination of health care integration across the near-full spectrum of health care services available to cohort participants. This linkage makes the identification and quantification of care pathways between these services possible over time, providing critical time-to-event data for a wide variety of health care service endpoints and patient outcomes. Key novel measures of health care integration include: the receipt of community-based (e.g. housing, detoxification, sobering, support recovery, discharge planning) and primary care services following discharge from ED and hospital; receipt of primary and acute care services following discharge from community-based addiction services; and patient movement between community-based services. These indicators will enable the study team to better identify barriers to care and health care integration for a patient population with complex care needs.

What has it found?

An initial draw of VCH data was retrieved in April 2017 and the linkage to the provincial administrative data was made available in August 2019. Our initial steps have been to assess the validity of the under-researched components of the database, provide descriptive analyses of these data to understand and communicate its strengths and weaknesses to our collaborators, and generate measures of health system performance.

Validation of ED and hospital diagnostic codes

Studies assessing the validity and comprehensiveness of regionalized databases providing community-based and acute care services are limited.45 Using a subset of the DTES-2GS cohort data, we examined the concordance between ED and hospital diagnostic codes for identifying mental health and SUDs and conducted analyses to identify patient- and ED visit-related factors independently associated with discordance.45 Among 48 116 pairs of ED and hospital discharge diagnoses codes, we found a high (overall agreement = 0.89, positive agreement = 0.74, kappa = 0.67) level of concordance for broad categories of mental health conditions, and a fair (overall agreement = 0.89, positive agreement = 0.31, kappa = 0.27) level of concordance for SUD. A comparable proportion of visits were classified as mental health-related in ED and hospital (21.7% vs 22.0%), and SUD was less likely to be indicated as the primary cause in ED as opposed to in hospital (3.8% vs 11.7%). In multiple regression analyses, ED visits occurring during holidays, weekends and overnight (9:00 pm-8:59 am) were associated with increased odds of discordance in identifying mental health disorders. These findings support the use of ED primary diagnosis codes in addition to hospital records for case attribution of these conditions, and provide evidence supporting the use of ED data for improvement of surveillance and monitoring of mental health and SUDs.

Descriptive analysis of community-based service referrals

The CommunityMart database, capturing records of community-based services provided outside acute care in the DTES, will serve as a platform to evaluate low-barrier addiction care, mental health care and housing programmes. We summarized different types of community-based services captured by the CommunityMart database, and longitudinally examined the selected types of community-based service referrals between 2009 and 2016 (Figure 3). The database captured service provided by 27 teams (Supplementary Table S3) providing primary care, other health care, group programmes, addiction care (e.g. detox, daytox, sobering unit and support recovery), home and community care, mental health care services and discharge planning in the DTES. A total of 18 470 (81.8%) DTES-2GS cohort participants accessed community-based services in the DTES during this period, totalling 196 577 new service referrals. During this period, 25% to 27% of all new referrals were for detox services, 4% to 6% were to sobering units and 8% to 10% were for mental health care services. A small number (926; 7.7%) of diagnosed PWOUD in the DTES-2GS cohort received new referrals for opioid agonist treatment in community-based services. Further, 141 (0.6%) members of the DTES-2GS cohort accessed community-based services as the first point of contact for substance use-related health issues, and 15 (0.1%) were captured only in the CommunityMart database.

Figure 3.

Overview of substance use disorders, mental health condition, and housing-related community-based service referrals among the DTES-2GS cohort: April 1, 2009, to March 31, 2017.a Legend: a. Individuals=18 470, all-cause referrals=196 577.

Integration into a provincial performance measurement system

To support the response to the opioid overdose public health emergency in British Columbia, a related project is under way to develop a comprehensive set of health system performance measures for PWOUD in British Columbia using best practices in validation and endorsement.46–50 Using a similarly defined cohort from provincial administrative data, 104 unique performance measures were developed to quantify: the cascade of care for OUD; compliance with clinical guidelines;51 health care integration, both across the spectrum of available health care services and specifically for treatment of concurrent disorders; and health care use. Given the unique availability of linkable data on community-based services in VCH, the DTES-2GS cohort was leveraged to develop 26 of these measures, focusing on health care integration between acute and community services.

For example, we quantified all-cause ED readmissions within 30 days of discharge among the provincial cohort, considering ED admissions after an individual’s first date of diagnoses. The percentage of all-cause ED readmissions increased from 49.5% in 2013 to 60.5% in 2017. We observed this increasing trend for provincial cohort participants with OUD and mental health conditions. In 2017, ED readmission rates were highest among cohort participants with OUD (62.7%) followed by mental health disorders (61.7%) (Figure 4). We also quantified the percentage of community-based service referrals within 30 days of ED discharge among DTES-2GS cohort participants with OUD. The percentage increased from 14.0% in 2013 to 17.5% in 2017 (Figure 5).

Figure 4.

All-cause emergency department readmission within 30 days of discharge.Legend: BL: Provincial cohort participants with opioid and other substance use disorder (baseline); PWOUD: Provincial cohort participants with opioid use disorder; PWMH: Provincial cohort participants with any mental health condition; Numerator = Emergency department (ED) discharges among cohort participantsa with an ED readmissionb for any cause within 30 days, denominator = ED dischargesa among cohort participantsa; a. Excludes emergency department admissions transferred to hospital. b. Includes emergency department readmissions transferred to hospital as well as discharged from emergency department. c. ED discharges from first day of diagnoses to 31 March 2017.

Figure 5.

Community-based service referrals within 30 days of emergency department discharge. Legend: Numerator: Emergency department discharges among DTES-2GS cohort participants with opioid use disordera with a community-based serviceb referral within 30 daysb. Denominator: Emergency department discharges among DTES-2GS cohort participants with opioid use disorderb. a. Excludes emergency department admissions transferred to hospital. b. Included case management, counselling, consultation, nursing, in-and outpatient addiction care, group program, primary care, older adult care, housing support, and other health support. c. Prior to emergency department or hospital admission

We identified 12 170 PWOUD within VCH in 2017. Of these, 9809 (80.6%) were in the DTES-2GS cohort. Our initial findings revealed significant gaps in treatment engagement in VCH. In 2017, 69.4% of PWOUD in VCH had ever accessed opioid agonist treatment, 52.6% of those ever engaged were currently on treatment and 74.0% of those on treatment were retained for at least 12 months.

What are the main strengths and weaknesses?

The DTES-2GS cohort is based on a novel linkage between provincial health administrative data and local data capturing community-based service interactions. A key strength of this cohort is that it provides a near-comprehensive record of health system interactions in the DTES and elsewhere across VCH which is unprecedented in the province. Linkage to the VCH CommunityMart database allows for the examination of a wide range of community-based services including detoxification, support recovery and specialty sobering units which are not captured elsewhere. Additionally, the linkage allows a robust examination of the integration between acute and community-based services which is not possible with provincial health administrative datasets alone. Health care integration is critical for providing adequate care and monitoring health outcomes of populations with complex health needs. In the DTES, a high proportion of the population experiences concurrent disorders2,29 and reports an inability to access primary care.17 This population relies heavily on community-based agencies or informal supports rather than formal health care services 2 and often presents to acute and emergency care as the first point of contact.11–13,52 This cohort will enable researchers to better identify barriers to care among marginalized populations.

To complete the capture of health care services in this dataset, we plan to request linkage to the British Columbia Centre for Disease Control HIV and hepatitis C virus testing registries and the British Columbia Centre for Excellence in HIV/AIDS laboratory and drug treatment programme registries. Linkage with additional surveillance and treatment data will allow for an expanded scope of research and a unique opportunity to accurately assess the health care use patterns of people living with HIV and viral hepatitis. Together with the existing cohort data, these databases will nearly cover the full spectrum of health care services provided in BC, some of which have never been linked to the broader provincial health data system.

We note several limitations. First, the degree of reporting to CommunityMart varies between community-based services. Previous to the DTES-2GS, reporting was based on site-specific documentation policies. Reporting is now mandated and is expected to increase as the DTES-2GS is implemented.53 Second, harm reduction services, including naloxone kit distribution and overdose prevention site visitation, constitute an important part of the continuum of care for PWSUD, particularly during the public health emergency in opioid overdose. However, these services do not require individuals to provide self-identifying information. Identification such as personal health number is needed for linkage across datasets and subsequent evaluation alongside other health care services. The current estimate of the PWSUD among the health service users in DTES is 22.2%.45 If the PWSUD do not use any other health services besides harm reduction services, the absence of individual-level data may also result in an underestimate of the PWSUD in the DTES. Finally, there are some noteworthy exclusions inherent in the provincial health administrative datasets. The PharmaNet database excluded medications dispensed in hospital, claims paid by the Federal government (Veterans, Royal Canadian Mounted Police, Armed Forces, Status First Nations and Federal inmates) and antiretroviral medications dispensed from the British Columbia Centre for Excellence in HIV/AIDS.38 The MSP database may exclude some services delivered by physicians in community-based settings, since these physicians are paid whether or not they submit a billing claim.54 Last, the NACRS database was limited in its data capture. This database was available after 1 April 2012, and only 29 hospitals in the province were reporting to NACRS at the end of follow-up. However, these hospitals provide ambulatory care to the majority of the provincial population (Supplementary Table S2).

Can I get hold of the data? Where can I find out more?

Requests and suggestions for analyses must have approval from all database stewards. Requests will be approved at the discretion of the British Columbia Ministry of Health and Vancouver Coastal Health. More information can be found at [https://www.popdata.bc.ca] and [http://dtes.vch.ca/]. Enquiries can be sent by e-mail to [Rachael.McKendry@vch.ca].

Supplementary data

Supplementary data are available at IJE online.

Author contributions

B.N., L.W. and D.P. conceptualized the study. F.H. and L.W. conducted data cleaning and analyses. F.H., L.P., L.W. and D.P. wrote the first draft. F.H., L.P., L.W., B.N., D.P., T.F.S., N.L., R.M., B.W., R.J., K.H., R.B. and C.M. provided critical review and edits to the manuscript. B.N. and C.M. secured funding for the study. All authors have approved the final article.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

We thank Population Data BC and Vancouver Coastal Health Authority staff involved in data access and procurement, including: Melissa Medearis, Michael Li, Joleen Wright, Christopher Mah, Janine Johnstone, Susan Sirett and Kacy Fehr.

Funding

This work was supported by Vancouver Coastal Health Authority and the Canadian Institutes of Health Research (GIR-145128).

Conflict of interest

None declared.

References

- 1. Milloy MJ, Montaner J, Wood E.. Barriers to HIV treatment among people who use injection drugs: implications for ‘treatment as prevention’. Curr Opinion HIV AIDS 2012;7:332–38. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Wang L, Panagiotoglou D, Min JE. et al. Inability to access health and social services associated with mental health among people who inject drugs in a Canadian setting. Drug Alcohol Depend 2016;168:22–29. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Hopwood M, Treloar C.. The drugs that dare not speak their name: Injecting and other illicit drug use during treatment for hepatitis C infection. Int J Drug Policy 2007;18:374–80. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Biancarelli DL, Biello KB, Childs E. et al. Strategies used by people who inject drugs to avoid stigma in health care settings. Drug Alcohol Depend 2019;198:80–86. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Paquette CE, Syvertsen JL, Pollini RA.. Stigma at every turn: Health services experiences among people who inject drugs. Int J Drug Policy 2018;57:104–10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Neale J, Tompkins C, Sheard L.. Barriers to accessing generic health and social care services: a qualitative study of injecting drug users. Health Soc Care Community 2007;16:147–54. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Canadian Centre on Substance Abuse. Systems Approach Workbook: Integration Substance Use and Mental Health Systems, Ottawa; CCSA, 2013.

- 8. Rush B, Fogg B, Nadeau L, Furlong A. On the integration of mental health and substance use services and systems: main report. Canadian Executive Council on Addictions. 2008.

- 9. Nosyk B, Fischer B, Sun H. et al. High levels of opioid analgesic co-prescription among methadone maintenance treatment clients in British Columbia, Canada: results from a population-level retrospective cohort study. Am J Addict 2014;23:257–64. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Hansagi H, Engdahl B, Romelsjö A.. Predictors of repeated emergency department visits among persons treated for addiction. Eur Addict Res 2012;18:47–53. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Kerr T, Wood E, Grafstein E. et al. High rates of primary care and emergency department use among injection drug users in Vancouver. J Public Health (Oxf) 2005;27:62–66. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Palepu A, Strathdee S, Hogg R. et al. The social determinants of emergency department and hospital use by injection drug users in Canada. J Urban Health 1999;76:409–18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Fairbairn N, Milloy M, Zhang R. et al. Emergency department utilization among a cohort of HIV-positive injecting drug users in a Canadian setting. J Emerg Med 2012;43:236–43. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Zhang L, Norena M, Gadermann A. et al. Concurrent disorders and health care utilization among homeless and vulnerably housed persons in Canada. J Dual Diagn 2018;14:21–31. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Nosyk B, Min JE, Colley G. et al. The causal effect of opioid substitution treatment on HAART medication refill adherence. AIDS 2015;29:965–73. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Olding M, Hayashi K, Pearce LA. et al. Developing a patient-reported experience questionnaire with and for people who use drugs: a community engagement process in Vancouver's Downtown Eastside. Int J Drug Policy 2018;59:16–23. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Brar R, Milloy MJ, DeBeck K. et al. Inability to access primary care clinics among people who inject drugs in a Canadian setting of universal health care. Canadian Family Physician. 2019. In press. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 18.Government of British Columbia. Provincial Health Officer Declares Public Health Emergency, Vancouver, BC: Government of British Columbia, 2016.

- 19.British Columbia Coroners Service. Illicit Drug Overdose Deaths in BC: January 1, 2009 to October 31, 2019. Burnaby, BC: British Columbia Coroners Service, 2019.

- 20.Vancouver Coastal Health. Overdose Prevention and Response. Vancouver, BC: Vancouver Coastal Health, 2017.

- 21.Government of British Columbia. Overdose Prevention., Vancouver, BC: Government of British Columbia, 2018.

- 22. Scheuermeyer F, Grafstein E, Buxton J. et al. Safety of a modified community trailer to manage patients with presumed fentanyl overdose. J Urban Health 2019;96:21–26. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.British Columbia Centre on Substance Use. Provincial Opioid Addiction Treatment Support Program. Vancouver, BC: British Columbia Centre on Substance Use, 2018.

- 24.Government of British Columbia. Opioid Use Disorder: Diagnosis and Management in Primary Care Vancouver, BC: Government of British Columbia, 2018.

- 25. Laing MK, Tupper KW, Fairbairn N.. Drug checking as a potential strategic overdose response in the fentanyl era. Int J Drug Policy 2018;62:59–66. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.British Columbia Ministry of Health. Psychiatric Medications Plan (Plan G), Victoria, BC: British Columbia Ministry of Health, 2018.

- 27.College of Physicians and Surgeons of British Columbia. Practice Standard: Prescribing Methadone. Vancouver, BC: College of Physicians and Surgeons of British Columbia, 2018.

- 28.Province of British Columbia. Ministry of Mental Health & Addictions. A pathway to hope: A roadmap for making mental health and addictions care better for people in British Columbia. 2019.

- 29. Linden IA, Mar IY, Werker GR, Jang K, Krausz M.. Research on a vulnerable neighbourhood - the Vancouver Downtown Eastside from 2001 to 2011. J Urban Health 2013;90:559–73. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Roe GW. Fixed in place: Vancouver's Downtown Eastside and the community of clients. BC Stud 2009;1:26. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Wilson-Bates DF . Lost in Transition: how a Lack of Capacity in the Mental Health System is Failing Vancouver’s Mentally Ill and Draining Police Resources Vancouver, BC: Vancouver Police Department, 2008.

- 32.Vancouver Coastal Health. The 2nd Generation Strategy Vancouver, BC: Vancouver Coastal Health, 2017.

- 33.Vancouver Coastal Health. Downtown Eastside Second Generation Health System Strategy: Design Paper. Vancouver, BC: Vancouver Coastal Health, 2015.

- 34.Vancouver Coastal Health. New Clinic and New Model of Care in the Downtown Eastside. Vancouver, BC: Vancouver Coastal Health, 2018.

- 35.Vancouver Coastal Health. DTES Connections Officially Opens in DTES. Vancouver, BC: Vancouver Coastal Health, 2017.

- 36.British Columbia Ministry of Health. Discharge Abstract Database (Hospital Separations). Victoria, BC: British Columbia Ministry of Health, 2017.

- 37.British Columbia Ministry of Health. Medical Services Plan (MSP). Victoria, BC: British Columbia Ministry of Health, 2017.

- 38.British Columbia Ministry of Health. PharmaNet. Victoria, BC: British Columbia Ministry of Health, 2017.

- 39.British Columbia Ministry of Health. National Ambulatory Care Reporting System (NACRS). Victoria, BC: British Columbia Ministry of Health, 2017.

- 40.British Columbia Vital Statistics Agency. Vital Statistics Deaths. Victoria, BC: British Columbia Ministry of Health, 2017.

- 41. Piske M, Zhou C, Min JE. et al. The cascade of care for opioid use disorder: a retrospective study in British Columbia, Canada. Addiction 2020;115:1482–93. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Canadian Institute for Health Information. Canadian Classification of Health Interventions (CCI) Ottawa: Canadian Institutes of Health Information, 2012.

- 43.Canadian Institutes of Health Information. Background Paper for the Redevelopment of the Acute Care Inpatient Grouping Methodology Using ICD-10-CA/CCI Classification Systems. Ottawa: Canadian Institutes of Health Information, 2004.

- 44.Canadian Institute for Health Information. Case Mix Group Plus (CMG+) Ottawa: Canadian Institutes of Health Information, 2018.

- 45. Wang L, Homayra F, Pearce LA. et al. Identifying mental health and substance use disorders using emergency department and hospital records: a population-based retrospective cohort study of diagnostic concordance and disease attribution. BMJ Open 2019;9:e030530. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.National Quality Forum. Opioids and Opioid Use Disorder Technical Expert Panel. Available from https://www.qualityforum.org/ProjectMaterials.aspx?projectID=89435.

- 47.Health Quality Ontario. How Indicators are Selected to Measure Ontario’s Health System Performance Toronto, ON: Health Quality Ontario, 2018.

- 48. Fitch K, Bernstein SJ, Aguilar MD. et al. The RAND/UCLA Appropriateness Method User's Manual 2001. No. MR-1269-DG-XII/RE:126. Santa Monica, CA: RAND:Corp; 2001.

- 49. Pronovost PJ, Lilford R.. A road map for improving the performance of performance measures. Health Aff 2011;30:569–73. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Hsu CC, Sandford BA.. The Delphi technique: Making sense of consensus. Pract Assess Res Eval 2007;12: 10. [Google Scholar]

- 51.Government of British Columbia. A Guideline for the Clinical Management of Opioid Use Disorder. Vancouver, BC: Government of British Columbia, 2017.

- 52. Gill PJ, Saunders N, Gandhi S. et al. Emergency department as a first contact for mental health problems in children and youth. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry 2017;56:475–82. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Vancouver Coastal Health. The New PARIS Clinical Care Plan Now Live. Vancouver, BC: VCH, 2016.

- 54.Government of British Columbia. Alternative Payments Program. Vancouver, BC: Government of British Columbia, 2018.

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.