Abstract

The COVID-19 pandemic caused France to impose a strict lockdown, affecting families' habits in many domains. This study evaluated possible changes in child eating behaviors, parental feeding practices, and parental motivations when buying food during the lockdown, compared to the period before the lockdown. Parents of 498 children aged 3–12 years (238 boys; M = 7.32; SD = 2.27) completed an online survey with items from validated questionnaires (e.g., CEDQ, CEBQ, HomeSTEAD). They reported on their (child's) current situation during the lockdown, and retrospectively on the period before the lockdown. Many parents reported changes in child eating behaviors, feeding practices, and food shopping motivations. When changes occurred, child appetite, food enjoyment, food responsiveness and emotional overeating significantly increased during the lockdown. Increased child boredom significantly predicted increased food responsiveness, emotional overeating and snack frequency in between meals. When parents changed their practices, they generally became more permissive: less rules, more soothing with food, more child autonomy. They bought pleasurable and sustainable foods more frequently, prepared more home-cooked meals and cooked more with the child. Level of education and increased stress level predicted changes in parental practices and motivations. This study provides insights in factors that can induce positive and negative changes in families' eating, feeding and cooking behaviors. This can stimulate future studies and interventions.

Keywords: Child eating behavior, Snacking, Food parenting practices, BMI, Boredom, Stress

1. Introduction

At the end of 2019, the highly contagious coronavirus SARS-CoV-2 causing a severe acute respiratory syndrome (COVID-19) has sparked a pandemic. Many countries worldwide were affected by the spread of this virus, forcing governments to protect their inhabitants by imposing strict rules. In France, a strict first lockdown took place from March 17 until May 10, 2020. During this period, schools were closed, working from home was enforced except for some specific professional domains (e.g., working in hospital, in food shops). Leaving your home was allowed only under certain circumstances and only after filling in a special certificate. Valid reasons to leave your home, indicated on this certificate, were for example essential work, grocery shopping, medical reasons, urgent family matters or assistance to vulnerable people, and open-air physical activities (limited to 1 h a day at a maximal distance of 1 km from your home).

The lockdown forced people to adapt their everyday behaviors to the new situation, including their food-related behaviors. This particular situation stimulated many researchers to study the impact of the lockdown on eating behaviors. Most studies have been conducted with adolescents or adults. For example, Di Renzo et al. (2020) studied eating habits and lifestyles changes during the lockdown among the Italian population (aged between 12 and 86 years). Marty, de Lauzon, Labesse & Nicklaus (2021) studied how changes in French adults’ food choice motives were related to changes in nutritional quality during the lockdown compared to the period before the lockdown. Pietrobelli et al. (2020) conducted a study in Italy on eating behavior with parents of children aged 6–18 years, but the sample was very small (N = 41) and the children all had obesity.

The current study is original and complementary to these researches as it focused specifically on changes in children's eating behaviors and families' feeding practices during the lockdown, compared to the period before the lockdown.

Since schools were closed and most people had to work from home or were technically unemployed, many children and adults had to consume all their meals at home. Parents were consequently responsible for their child's food intake throughout the whole day, and this could be challenging in terms of time (additional meal planning, food shopping, food preparation), especially for those parents who were still working. The pandemic also faced some parents with changed accessibility and availability of foods and food insecurity, in particular those parents who were financially vulnerable (Loopstra, 2020).

The psychological states (fear, depressive symptoms, stress, etc.) linked to the COVID-19 pandemic (Jiao et al., 2020; Wang et al., 2020) possibly also affected children's and parents' eating behaviors and consequently also their motivations when buying foods. In fact, previous studies have shown that the experience of stress and negative emotions leads people to overeat and makes them reach for so-called “comfort foods”, rich in sugar and calories (Evers, Dingemans, Junghans, & Boevé, 2018; Michels et al., 2012; Rodríguez-Martín & Meule, 2015). Increased levels of boredom have previously also been associated with increased energy intake (Moynihan et al., 2015).

Similarly, parents possibly adapted their parental feeding practices, i.e., the behavioral strategies to control what, how much, when, and where the child eats (Ventura & Birch, 2008), to this unseen situation. On the one hand, because of child-driven reasons: to meet the changed eating and emotional needs of their child at home. On the other hand, because of situation-driven or parent-driven reasons: changes in families' routines could for example affect the timing of meals or parents could have provided foods to entertain their children while working from home. As parental feeding practices have an important influence on child eating behavior (Birch, 1999), it is of importance to explore how these practices may have changed during the lockdown to obtain a more complete picture of the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on the food domain. Moreover, young children are very dependent on their parents for food intake (e.g., Poti & Popkin, 2011): what parents buy and their motivations when buying foods for their child influence children's eating behavior. (Rigal, Chabanet, Issanchou, & Monnery-Patris, 2012). It is thus important to differentiate their food shopping motivations from adults in general.

Therefore, this study's first goal was to evaluate possible changes in eating behaviors in children aged 3–12 years, in parental eating and cooking behaviors, in parental feeding practices, and also in parental motivations when shopping for food during the lockdown, compared to the period before the lockdown. The age range of 3–12 years was chosen because these children are still highly dependent on their caregivers for their food intake. Given the results of previous studies highlighting the impact of stress and of boredom on eating behaviors (Evers et al., 2018, Michels et al., 2012; Rodríguez-Martín & Meule, 2015; Moynihan et al., 2015), the second goal of this study was to explore possible links between, on the one side, changes in the child's level of boredom at home, changes in parental stress at home, and child and parental socio-demographic variables, and, on the other side the changes in children's and parental eating behaviors, practices and motivations for food shopping during the lockdown.

2. Method

2.1. Recruitment and ethics

An online questionnaire was used to obtain data for this study. Parents were recruited via an agency disposing of a panel of participants all over France. Prerequisites to participate were (1) having a child aged 3–12 years, and (2) no recent changes in the parent's or child's eating behaviors due to other reasons than a change of habits linked to the lockdown (e.g., following a new diet to lose weight, changed eating behaviors because of a medical treatment, changed eating behaviors because of religious reasons). The questionnaire was anonymous and on the first page of the questionnaire, parents were required to tick a box indicating that they understood and accepted the study information and data protection policy. The questionnaire was open for participation from the 30th of April until the 10th of May 2020 (the end of the strict lockdown in France). Participants received a voucher of six euros for questionnaire completion. An ethical approval (n°20–686) was granted for this study by the Institutional Review Board (IRB00003888, IORG0003254, FWA00005831) of the French Institute of Medical Research and Health, and a study registration was done by the data protection service involved (CNRS).

2.2. Measures

2.2.1. Demographics

Parents were asked to report the sex of the child and his/her date of birth to ensure a correct calculation of the child's age and his/her normed body mass index’ (BMI) z-score. Once these calculations were completed, the child's birth date was deleted to minimize information that could possibly help to identify the participants. Parents were also asked to report their own sex, age, relationship status, number of children in the household, level of education, type of housing, employment status before and during the lockdown, and their perception of their financial status. In addition, to describe the general eating habits of our sample during the lockdown, parents were asked to report the number of meals (breakfast, lunch, mid-afternoon snack, dinner) their child generally took at home on a weekly basis (ranging from 1 to 7) during the lockdown, and if they took more, less, or the same number of meals with their child compared to the period before the lockdown.

2.2.2. Child eating behaviors

2.2.2.1. Appetite, food enjoyment, food pickiness

The Children's Eating Difficulties Questionnaire (CEDQ; Rigal et al., 2012) was used to measure the child's levels of appetite (three items; e.g., My child eats small quantities (even if the food is liked) (Reversed item)), food enjoyment (three items; e.g., My child looks forward to mealtimes), and food pickiness (three items; e.g., My child only eats a small variety of foods). Parents were asked to rate their agreement with each item on a five-point Likert scale (Strongly disagree, Disagree, Neither agree nor disagree, Agree, Strongly agree), according to their child's eating behavior during the lockdown, and retrospectively for the period before the lockdown. A score was calculated for each period. Scores were calculated in such way so higher scores indicated a higher appetite, a higher food enjoyment, and a higher level of food pickiness in the child.

2.2.2.2. Food responsiveness and emotional overeating

The Children's Eating Behavior Questionnaire (CEBQ; Wardle, Guthrie, Sandreson, Rapoport, 2001) was used to measure the child's levels of food responsiveness (five items; e.g., My child is always asking for food), and emotional overeating (four items; e.g., My child eats more when anxious). Parents rated their agreement with each item on a five-point scale (Never, Rarely, Sometimes, Often, Always), for both the period before and during the lockdown. For emotional overeating, we also added a sixth answer option: not applicable, as we were not sure if all children would have already presented all emotions (worried, annoyed, anxious, boredom) during the lockdown. Higher scores indicated higher food responsiveness and more emotional overeating.

2.2.2.3. Snacking frequency and types of snacks

In France, the mid-afternoon snack (“goûter”) is a common practice and is perceived as an additional meal beside breakfast, lunch and dinner, especially in children (Francou & Hébel, 2017, pp. 1–4). We therefore distinguished between the frequency of the mid-afternoon snack (which usually also includes a drink) and the frequency of other snacks/drinks in between meals. We clearly explained the difference between both types of snacking occasions to parents in the instructions of the questions. For the mid-afternoon snack, parents were asked to rate the child's frequency of this snacking occasion on a four-point scale (Less than once a week, 1–3 times per week, 4–6 times per week, Every day), for both the period before and during the lockdown. For other snacks/drinks, parents rated the frequency on a seven-point scale (Less than once a week, 1–3 times per week, 4–6 times per week, once per day, Twice a day, Three times a day, 4 or more times a day), also for both the period before and during the lockdown. We gave examples of possible snacks/drinks (e.g., candy, piece of bread, fruit, compote, yoghurt, salty or sweet biscuits) to illustrate that any food and drink, except water, should be counted as a snack/drink.

We asked parents as well about the types of foods their child usually consumed during snack times: “When your child has a mid-afternoon snack or a snack/drink in between meals, how often does (s)he consume the following types of foods and drinks?”. The frequency of each type of food/drink (Table 4) was rated on a five-point scale (Never, Rarely, Sometimes, Often, Always), for both the period before and during the lockdown. The selection of the types of foods and drinks was based on the food groups presented in a French food consumption report (Anses, 2017).

Table 4.

Snacking frequency: percentage of total sample of parents (N = 498) reporting a change for their child (%), mean scores before and during the lockdown (M before and M during) for these children with changed behaviors, standard deviations (SD), difference in mean scores (M difference = M during – M before), and paired-samples t-tests (t value and p value).

| Types of food/drinks consumed during (mid-afternoon) snacks | % | M (SD) before | M (SD) during | M difference | t | p |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Candy, chocolate | 26 | 2.57 (0.86) | 3.47 (0.98) | 0.89 | 9.26 | <0.001 |

| Fruit juice | 22 | 2.36 (1.01) | 3.09 (1.10) | 0.73 | 7.53 | <0.001 |

| Soda | 11 | 2.13 (0.83) | 3.02 (0.99) | 0.89 | 7.24 | <0.001 |

| Chips, salty biscuits | 13 | 2.33 (1.06) | 3.17 (1.06) | 0.83 | 6.47 | <0.001 |

| Ice cream | 27 | 2.20 (0.71) | 2.66 (1.14) | 0.58 | 5.68 | <0.001 |

| Pastries, cake, sweet cookies | 30 | 2.97 (0.95) | 3.48 (1.09) | 0.52 | 4.76 | <0.001 |

| Cream dessert | 15 | 2.20 (0.94) | 2.80 (1.13) | 0.61 | 4.35 | <0.001 |

| Milks | 19 | 2.53 (1.00) | 3.06 (1.26) | 0.54 | 4.02 | <0.001 |

| Yoghurt, cheese, quark | 21 | 2.39 (1.00) | 2.90 (1.16) | 0.50 | 3.95 | <0.001 |

| Fresh and dried fruits | 23 | 2.63 (1.00) | 3.00 (1.15) | 0.37 | 3.29 | 0.001 |

| Nuts | 10 | 2.23 (0.88) | 2.69 (1.15) | 0.46 | 2.68 | 0.010 |

| Bread | 28 | 2.70 (0.91) | 2.92 (1.16) | 0.22 | 1.96 | 0.052 |

| Sandwich, pizza, savory pies | 4 | 2.58 (0.69) | 3.05 (1.08) | 0.47 | 1.69 | 0.108 |

| Cheese | 11 | 2.43 (0.95) | 2.66 (1.18) | 0.23 | 1.29 | 0.204 |

| Cereals, cereal bars | 22 | 2.42 (0.86) | 2.52 (1.11) | 0.10 | 0.82 | 0.414 |

| Compote, fruits in syrup | 25 | 3.26 (1.11) | 2.97 (1.20) | −0.29 | −2.24 | 0.027 |

Answer modalities ranged from never (1) to always (5).

Significant results (p < 0.05) in bold.

2.2.3. Child boredom

Parents were asked to report how often their child was bored at home on a five-point scale (Never, Rarely, Sometimes, Often, Always), for both the period before and during the lockdown. Higher scores indicated higher levels of boredom at home.

2.2.4. Parental feeding practices

Parental feeding practices were derived from the Home Self-Administered Tool for Environmental Assessment of Activity and Diet Family Food Practices Survey (HomeSTEAD; Vaughn, Dearth-Wesley, Tabak, Bryant, & Ward, 2017). This 86-item instrument captures five coercive control practices (CCP), seven autonomy support practices (ASP), and twelve structure practices (SP). We selected seven practices we thought to be susceptible for change during the lockdown: Soothing with food (CCP; four items; e.g., I give my child something to eat or drink when she or he is bored or worried, even if I know she or he is not hungry), Guided choices - when (ASP; three items; e.g., I let my child eat between meals whenever she or he wants), Guided choices - what (ASP; three items; e.g., I allow my child to choose what she or he has for snacks), Guided choice - amount (ASP; three items; e.g., During meals, I allow my child to decide when she or he has had enough to eat.), Rules and limits around unhealthy foods (SP; four items; e.g., I place limits on the sweet or salty snacks (candy, ice cream, cake, potato chips, tortilla chips) that my child eats), Meal setting (SP; three items; e.g., Do you limit snacking to designated places in your home?; I insist my child eats meals at the table.), and Atmosphere of meals (SP; three items; e.g., Dinner time is usually a pleasant time for the family). Parents rated their use of these practices on a five-point scale (Never, Rarely, Sometimes, Often, Always), for both the period before and during the lockdown. Higher scores indicated the use of more soothing with foods, more child autonomy, more rules and limits, a stricter meal setting, and a more positive meal atmosphere. The items were translated from English to French by several researchers of the team, and some questions were slightly modified; to adapt them to the French situation (e.g., mid-afternoon snack “goûter” vs. other snacks/drinks) or to be more uniform within the entire questionnaire (Supplementary data).

One additional feeding practice “Feeding on a schedule” was selected for this study. This three-item dimension (e.g., During the week, do you make him/her eat at set times?) was retrieved from the Infant Feeding Questionnaire (IFQ; Baughcum et al., 2001) and has already been validated for the use in French samples (Monnery-Patris, Rigal, Peteuil, Chabanet, & Issanchou, 2019). Parents rated their answers on a five-point scale (Never, Rarely, Sometimes, Often, Always), for both the period before the lockdown and during the lockdown. Higher scores indicated stricter times for eating.

2.2.5. Parental motivations for buying foods

Changes in parental motivations for buying foods were assessed using 19 items. Most of these items were retrieved from the Questionnaire relating to Parental Motivations when buying food for children (Rigal et al., 2012). This 17-item instrument captures six dimensions of parental motivations: convenience (e.g., easy to cook), weight-control (e.g., not too high in calories), natural-content (e.g., fresh), health-concern (e.g., high in vitamins), preference (e.g., adapted to children's taste), price (e.g., good price-quality). Originally, parents are asked to rate their agreement with each item: e.g.,“For my child, I am careful to buy food which are… easy to cook” on a five-point scale ranging from “very wrong for me” (1) to “very true for me” (5). For this study, we wanted to evaluate the changes in parental motivations (during vs. before the lockdown) in a direct way, so we reformulated all items to e.g., “Compared to the period before the lockdown, you buy and prepare foods for your child(ren) that are… easy to cook”. Parents indicated a possible difference on a five-point scale (Much less often than before, A bit less often than before, As often as before, A bit more often than before, Much more often than before). The answers were rescored to −2, −1, 0, 1, 2 respectively so negative scores would indicate a decrease, zero no change, and positive scores an increase. Four original items were deleted because they were less relevant for this study, and the dimensions sustainability (three items, i.e., locally produced; seasonal products; biological), pleasure (one item: pleasurable), conservation (one item: easy to store for a longer period) and comfort (one item: comfort foods) were added.

2.2.6. Parental eating and cooking behaviors and stress level at home

Parents were asked to rate their own frequency of intake of a mid-afternoon snack and of other snacks/drinks in between meals using the same scales as for the children, also for both the period before and during the lockdown.

Parents were also asked to report how often they felt stressed or tensed at home on a five-point Likert scale (Never, Rarely, Sometimes, Often, Always), for both the period before and during the lockdown. Higher scores indicated higher levels of stress at home.

Parents were also asked to report changes in their emotional eating, in the preparation of homemade dishes, in the preparation of comfort foods, and in the time they spent cooking with their child(ren). These changes were directly rated on a five-point scale (Much less than before, A bit less than before, As often as before, A bit more than before, Much more than before). The answers were rescored to −2, −1, 0, 1, 2 respectively so negative scores would indicate a decrease, zero no change, and positive scores an increase.

The questionnaire also contained three open questions to ask parents about their food-related experiences during the COVID-19 lockdown. The results of these questions are not presented in this paper.

2.2.7. Anthropometric data for parent and child

As measuring and weighing participants was impossible for the researchers during the COVID-19 lockdown, parents were asked to self-report their current weight and height, and the weight and height of their child. Parents were encouraged to report recent child measurements carried out by health professionals from the child's medical health book. If no recent measures were available in this book, or if the measurements of height and weight were not carried out within a time span of two months, we asked them to measure and/or weigh their child at home. Parents' and children's BMI were calculated by dividing their weight (kg) by their height (m) squared. For children, normed BMI z-scores were calculated using WHO's (2006) international growth standards for children.

2.3. Statistical analyses

R version 3.6.1 (R Core Team, 2019) was used to clean and analyse the data.

2.3.1. Data cleaning

Questionnaires were excluded when the child was younger than 3 years or older than 12.9 years (n = 4), when the child had an illness (different from food allergy) susceptible of influencing his/her eating (e.g., autism, thyroid disease; n = 8), or when the child was born very premature (<28 weeks of gestation; n = 0). When information on age, sex, illness or prematurity was missing, these questionnaires were also excluded (n = 20).

2.3.2. Preliminary analyses

Cronbach's alphas were calculated to test the psychometric properties of the measures used for evaluating child eating behaviors and parental feeding practices before and during the lockdown. When these alphas were too low (<0.60), confirmatory factor analyses (CFA) with a SEM approach (Bollen, 1989; Kaur et al., 2006) were performed to gain more insights in the factor structures and to potentially optimize them. Acceptable Cronbach alphas were observed for all child eating behaviors (ranging between 0.79 and 0.87). For parental feeding practices, some Cronbach's alphas were acceptable (ranging between 0.63 and 0.81; for soothing with food, rules and limits around healthy food, atmosphere of meals), some were borderline acceptable (ranging between 0.52 and 0.57; for guided choices - when, and feeding on a schedule) and some were found lower (ranging between 0.31 and 0.41; for guided choices – what and amount, and meal setting). In contrast, the CFAs indicated acceptable factor loadings for all practices, except for guided choices - amount. One item was deleted for this dimension because the factor loading was very low. Details are available in Supplementary data.

2.3.3. Primary analyses

Scores were calculated for each dimension by averaging the scores of the corresponding items, for the period of the lockdown, and for the period before the lockdown. For the dimensions emotional overeating and soothing with food, the answer option “not applicable” was coded as missing value. For emotional overeating, 22 parents responded with “not applicable” to all corresponding items, and for soothing with food, six parents responded with “not applicable” to all items. These parents thus did not report changes in this behavior/practice during the lockdown compared to before the lockdown. Proportions of individuals showing a change (scoreduring lockdown - scorebefore lockdown ≠ 0) were calculated for each child behavior and each parental feeding practice. For those children/parents for whom changes were reported, paired-samples t-tests were conducted for each behavior/practice in order to compare mean scores of both periods (M during lockdown - M before lockdown). Simple regressions were performed to study the effects of changes in level of child boredom at home, child age, child sex, and child z-BMI (as a continuous variable) on changes in child eating behaviors. Simple regressions were also used to study the effects of parental demographics (parent's sex, BMI, relationship status, level of education, work status during lockdown, perception of financial status) and changes in parental stress levels at home, on changes in parental feeding practices, changes in parental motivations for buying foods, and on changes in parental cooking behaviors. Whenever the results of these simple regressions indicated multiple significant predictors for a given dependent variable, we subsequently performed a multiple regression analysis to verify if the relations remained significant after controlling for the effects of the other predictors. In all regression analyses, the dependent variables only included the children/parents for whom changes in their behaviors, practices or motivations were reported. This approach was chosen since this study was specifically designed to focus on possible predictors of the observed changes, but also for statistical reasons (i.e., to meet the assumption of normality, and to maintain a homogenous variance). The significance level was set at p < 0.05 for all analyses. Our analytic plan was pre-specified in our study file and submitted to the ethical committee before the data were collected.

3. Results

3.1. Participants

A sample of 498 parents of children aged 3.0–12.3 years (47.8% boys; M age = 7.3; SD = 2.2) was retained for analyses after data cleaning. The demographics for the parents are presented in Table 1 . According to parental reports of child weight and height, 8% of children aged 3.0–5.0 years had underweight (z-BMI < −2), 68% had a normal weight (−2 ≤ z-BMI < 1), 18% were at risk for overweight (1 ≤ z-BMI < 2), 5% had overweight (2 ≤ z-BMI < 3), and 1% had obesity (z-BMI > 3) (categories derived from WHO, 2006). Among the children aged 5.1–12.3 years, 6% had underweight (z-BMI < −2), 69% had a normal weight (−2 ≤ z-BMI < 1), 15% had overweight (1 ≤ z-BMI < 2), and 9% had obesity (z-BMI > 2) (categories derived from de Onis et al., 2007). During the lockdown, the children in this study took on average 6.8 breakfasts a week at home, 6.8 lunches, and 7.0 dinners. Fourteen percent of parents reported taking more breakfasts with their child during the lockdown than before, 85% reported no difference, and 1% of parents reported a decrease. For lunch, 59% of parents reported an increase in lunches taken with their child, 37% no difference, and 3% a decrease. Forty-six percent of parents reported an increase in the number of mid-afternoon snacks taken with their child, 50% no difference, and 4% a decrease. For dinner, 14% of parents reported an increase in dinners taken with their child, 86% no difference, and 1% a decrease.

Table 1.

Demographics for parents.

| Demographic | Parents (n = 498) |

|---|---|

| Sex (female/male) [%] | 71.7/28.3 |

| Age [%] | |

| 25–34 years | 30.5 |

| 35–49 years | 67.9 |

| 50–64 years | 1.6 |

| BMI [%] | |

| Underweight (<18.5 kg/m2) | 3.4 |

| Normal weight (18.5–25 kg/m2) | 51.6 |

| Overweight (25–30 kg/m2) | 29.7 |

| Obesity (≥30 kg/m2) | 15.3 |

| Relationship status (couple/single parent) [%] | 89.2/10.8 |

| Number of children in household, mean (SD) | 2.1 (0.9) |

| Level of education [%] | |

| Low (secondary studies degree or lower) | 33.5 |

| Middle (higher technology degree or first cycle of higher education) | 26.7 |

| High (university degree) | 39.8 |

| Type of housing [%] | |

| Apartment without a balcony or a terrace | 6.8 |

| Apartment with a balcony or terrace | 20.7 |

| House without a garden | 1.0 |

| House with a garden | 71.5 |

| Work status before the lockdown [%] | |

| Working (part-time or full-time) | 85.1 |

| Unemployed, job seeker | 4.8 |

| Other (e.g., student, parental leave, parent at home) | 11.0 |

| Work status during the lockdown [%] | |

| Working outside the house (part-time or full-time) | 20.7 |

| Working from home (part-time or full-time) | 35.1 |

| At home, not working | 35.1 |

| Other (e.g., student) | 9.0 |

| Perception of financial situation [%] | |

| You can't make ends meet without going into debt | 3.2 |

| You get by but only just | 12.9 |

| Should be careful | 34.9 |

| It's OK | 36.3 |

| At ease | 11.6 |

| I do not want to answer | 1.0 |

3.2. Children

3.2.1. Changes in child eating behaviors (during versus before lockdown)

Sixty percent of parents reported a change in at least one dimension of their child's eating behaviors during the lockdown compared to the period before the lockdown. When looking only at the children with changed behaviors, paired-samples t-tests resulted in a significant increase for all behaviors but food pickiness (Table 2 ). The highest increases in mean score were observed for emotional eating (+0.61) and for food responsiveness (+0.44).

Table 2.

Child eating behaviors: percentage of total sample of parents (N = 498) reporting a change for their child (%), mean scores before and during the lockdown (M before and M during) for these children with changed behaviors, standard deviations (SD), difference in mean scores (M difference = M during – M before), and paired-samples t-tests (t value and p value).

| Child eating behavior | % | M (SD) before | M (SD) during | M difference | t | p |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Emotional overeatinga | 31 | 2.43 (0.74) | 3.05 (0.91) | 0.61 | 12.43 | <0.001 |

| Food responsivenessa | 45 | 2.46 (0.70) | 2.90 (0.93) | 0.44 | 11.49 | <0.001 |

| Food enjoymentb | 28 | 2.69 (0.58) | 2.96 (0.86) | 0.27 | 3.87 | <0.001 |

| Appetiteb | 33 | 2.18 (0.76) | 2.30 (0.93) | 0.12 | 1.98 | 0.049 |

| Food pickinessb | 20 | 2.97 (0.89) | 2.85 (1.01) | −0.12 | −1.41 | 0.162 |

Significant results (p < 0.05) in bold.

Answer modalities ranged from never (1) to always (5).

Answer modalities ranged from strongly disagree (1) to strongly agree (5).

In this study, two types of snacking were studied: the mid-afternoon snack (perceived as a meal for children in France) and snacks/drinks in between meals. The frequency of the mid-afternoon snack increased in 15% of children (during versus before the lockdown), decreased in 9%, and did not change in 76% of children. The majority of children already had a daily mid-afternoon snack before the lockdown, and maintained this habit during the lockdown (Table 3 ). Parents reported an increase in snack frequency in between meals in 36% of children, a decrease in 4% of children, and no change in 60% of children.

Table 3.

Frequency of mid-afternoon snacks and of snacks/drinks in between meals for all children and all parents (N = 498), before and during the lockdown.

| Children |

Parents |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| before (%) | during (%) | before (%) | during (%) | |

| Mid-afternoon snacks | ||||

| < 1 time a week | 1 | 1 | 39 | 21 |

| 1–3 times per week | 8 | 4 | 25 | 26 |

| 4–6 times per week | 13 | 10 | 12 | 18 |

| Every day | 78 | 84 | 25 | 34 |

| Snacks/drinks in between meals | ||||

| < 1 time a week | 51 | 39 | 53 | 45 |

| 1–3 times per week | 20 | 19 | 24 | 22 |

| 4–6 times per week | 6 | 9 | 6 | 9 |

| Once a day | 16 | 16 | 11 | 14 |

| Twice a day | 4 | 12 | 4 | 6 |

| 3 times a day | 1 | 3 | 1 | 2 |

| 4 or more times a day | 2 | 3 | 1 | 3 |

Concerning the types of foods consumed by the children during (mid-afternoon) snack occasions, 66% of parents reported at least one change in consumption during the lockdown versus before. When studying only the children with a change in their consumption, paired-samples t-tests resulted in a statistically significant increase in mean scores (M during lockdown - M before lockdown) for candy/chocolate, fruit juices, sodas, chips/salty biscuits, ice creams, pastries/cake/sweet cookies, cream dessert, milks, yoghurt/cheese/quark, fresh and dried fruits, and nuts. A significant decrease in the consumption of compote/fruits in syrup was observed (Table 4 ).

3.2.2. Links with child boredom, age, sex, and z-BMI

Forty-five percent of parents reported no change in their child's level of boredom at home during the lockdown compared to the period before the lockdown, 53% reported an increase in level of boredom, and 2% a decrease. A paired-samples t-test performed on the scores of the children for whom changes were reported (n = 276) indicated a significant increase in mean score of level of boredom (+1.20, t(275) = 26.82, p < 0.001; M before = 2.28, SD before = 0.67; M during = 3.48, SD during = 0.70).

Simple regressions indicated that a greater increase in children's level of boredom at home (during vs. before lockdown) was significantly linked with a greater increase in emotional overeating, in food responsiveness and in snack frequency in between meals (Table 5 ). Simple regressions also indicated that child age, child sex and child z-BMI were not significant predictors for changes in child boredom levels, neither for changes in child (mid-afternoon) snack frequency, nor for changes in child eating behaviors, except for a significantly smaller increase in food responsiveness in children with higher BMI z-scores (β = −0.07, t = −2.96, p < 0.001). The results of these regression analyses, significant and non-significant, can be found in Supplementary data.

Table 5.

Simple linear regression models with the changes in child eating behaviors (when change occurred) as dependent variables, and the change in child level of boredom as independent variable.

| Change in | Df | Estimate | Std. Error | t | p |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Emotional overeating | 150 | 0.20 | 0.05 | 3.59 | <0.001 |

| Food responsiveness | 224 | 0.14 | 0.04 | 3.26 | <0.001 |

| Food enjoyment | 135 | 0.08 | 0.08 | 1.03 | 0.30 |

| Appetite | 164 | −0.02 | 0.07 | −0.34 | 0.74 |

| Food pickiness | 96 | 0.01 | 0.09 | 0.14 | 0.89 |

| Mid-afternoon snack frequency | 116 | −0.19 | 0.15 | −1.27 | 0.21 |

| Snack frequency in between meals | 198 | 0.28 | 0.10 | 2.78 | 0.01 |

Significant results (p < 0.05) in bold.

3.3. Parents

3.3.1. Changes in parental feeding practices

Sixty percent of parents reported at least one change in their feeding practices during lockdown compared to the period before the lockdown. When including only the parents who reported a change, paired-samples t-tests resulted in a significant increase in mean scores for soothing with food, guided choices - when, what and amount, and meal atmosphere. A significant decrease was observed for rules and limits around unhealthy foods, meal setting, and feeding on a schedule (Table 6 ). The greatest increases in mean score were observed for soothing with food (+0.43) and guided choices - when (+0.36), the greatest decrease was observed for feeding on a schedule (−0.40).

Table 6.

Parental feeding practices: percentage of total sample of parents (N = 498) reporting a change (%), mean scores before and during the lockdown (M before and M during) for these parents with changed practice, standard deviations (SD), difference in mean scores (M difference = M during – M before), and paired-samples t-tests (t value and p value).

| Parental feeding practice | % | M (SD) before | M (SD) during | M difference | t | p |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Soothing with food | 18 | 1.62 (0.61) | 2.06 (0.75) | 0.43 | 11.44 | <0.001 |

| Guided choices - whena | 26 | 1.60 (0.57) | 1.96 (0.64) | 0.36 | 8.79 | <0.001 |

| Guided choices - amounta | 14 | 2.59 (0.88) | 2.89 (0.82) | 0.30 | 4.00 | <0.001 |

| Guided choices - whata | 22 | 2.33 (0.68) | 2.50 (0.65) | 0.18 | 3.41 | <0.001 |

| Meal atmosphere | 23 | 4.01 (0.73) | 4.28 (0.76) | 0.27 | 4.05 | <0.001 |

| Rules and limits around unhealthy foods | 27 | 3.78 (0.73) | 3.68 (0.69) | −0.10 | −2.40 | 0.018 |

| Meal settingb | 13 | 4.03 (0.63) | 3.84 (0.54) | −0.20 | −3.72 | <0.001 |

| Feeding on a schedule | 31 | 4.29 (0.56) | 3.90 (0.61) | −0.40 | −8.40 | <0.001 |

Answer modalities ranged from never (1) to always (5).

Significant results (p < 0.05) in bold.

Higher scores for guided choice indicate higher levels of autonomy granted to the child.

Meal setting refers to the place where the child eats, higher scores indicate stricter rules.

3.3.2. Changes in parental motivations for buying foods

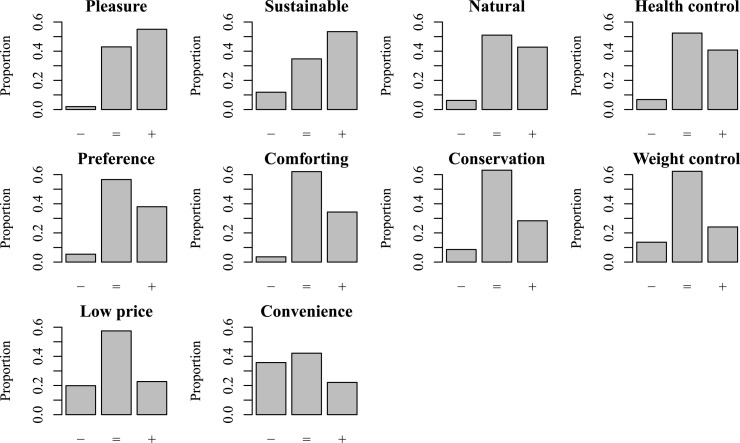

Eighty-five percent of parents reported at least one change in their motivations to buy and prepare certain foods for their child(ren) during the lockdown compared to the period before the lockdown. For each motivation dimension, proportions of parents who reported no change, a decrease, or an increase are presented in Fig. 1 . Greatest increases in motivation were observed for buying pleasurable and sustainable foods. The greatest decrease in motivation was observed for buying convenient foods.

Fig. 1.

Proportions of parents who reported a decrease (−), no difference (=), and an increase (+) in their motivation to buy/prepare certain foods for their child(ren).

3.3.3. Changes in parental eating and cooking behaviors

The frequency of the mid-afternoon snack increased in 35% of parents (during versus before the lockdown), decreased in 4%, and did not change in 61% of parents. Thirty-one percent of parents reported an increase in their snack frequency in between meals, 8% reported a decrease, and 62% no change. The frequencies of both snack occasions in parents before and during the lockdown are presented in Table 3. When asked if the lockdown and the accompanying emotions (e.g., boredom, stress, anxiety) induced parents to have more, the same or less desire to eat during the lockdown than before, 46% of parents answered that they felt more like eating than before, 41% of parents reported no change, and 14% of parents reported feeling less like eating than before.

When asked about the preparation of homemade dishes, 66% of parents reported preparing more homemade dishes than before, 30% reported no change, and 4% of parents reported preparing less homemade dishes. When asked about the preparation of comforting foods or recipes, 57% of parents reported preparing more comforting foods or recipes, 40% reported no change, and 3% reported preparing less. When asked about the time they spent cooking with their child(ren), 71% of parents reported spending more time cooking with their child(ren), 26% reported no change, and 2% reported spending less time cooking together.

3.3.4. Links with changes in parental level of stress and parental demographics

3.3.4.1. Effects of changes in parental stress level on parental feeding practices

Forty-four percent of parents reported no change in their level of stress at home during the lockdown compared to the period before the lockdown. An increase in level of stress was reported by 42% of parents and a decrease by 14%. A paired-samples t-test performed on the scores of the parents with a change in their stress level (n = 280), indicated a significant increase in mean score of stress level with +0.59 (t(279) = 7.70, p < 0.001; M before = 2.74, SD before = 0.86; M during = 3.33, SD during = 0.93).

Simple regressions indicated that greater increases in stress level were linked with greater increases in guided choice - amount (more autonomy for the child to decide the amount of intake) (Table 7 ): on average, guided choice – amount increased during the lockdown (Table 6), and this increase was even greater if stress level increased. Also, on average, the meal time atmosphere quality improved during the lockdown (Table 6), but not for those parents who became more stressed at home (Table 7). More specifically, compared to the period before the lockdown, there was no improvement in meal atmosphere quality if parents’ stress level increased by one unit, and there was a decrease in atmosphere quality if the stress level increased by more than one unit.

Table 7.

Simple linear regression models with the changes in parental feeding practices (when change occurred) as dependent variables and the change in parental level of stress as independent variable.

| Change in | Df | Estimate | Std. Error | t | p |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Soothing with food | 89 | −0.04 | 0.03 | −1.38 | 0.17 |

| Guided choices – when | 128 | 0.01 | 0.03 | 0.43 | 0.67 |

| Guided choices – what | 107 | 0.02 | 0.04 | 0.49 | 0.62 |

| Guided choices – amount | 68 | 0.15 | 0.06 | 2.38 | 0.02 |

| Meal atmosphere | 115 | −0.34 | 0.04 | −7.67 | <0.001 |

| Rules and limits around unhealthy foods | 133 | 0.03 | 0.04 | 0.82 | 0.41 |

| Meal setting | 65 | −0.08 | 0.06 | −1.35 | 0.18 |

| Feeding on a schedule | 154 | −0.06 | 0.04 | −1.42 | 0.16 |

Significant results (p < 0.05) in bold.

3.3.4.2. Effects of parental demographics on changes in parental feeding practices

Some parental demographics were also identified as significant predictors of changes in parental feeding practices. Simple regressions indicated that the decrease in rules and limits around unhealthy foods (Table 6) was even greater among parents with a higher level of education (β = −0.08, t = −2.45, p = 0.02; see Supplementary data). Feeding on schedule decreased on average (Table 6), but a smaller decrease was observed in more educated parents (β = 0.11, t = 2.56, p = 0.01; see Supplementary data). In other words, parents became more permissive regarding the times to eat, but to a lower extent among higher educated parents. Parental sex significantly predicted changes in guided choices – when (β = 0.22, t = 2.32, p = 0.02): mothers showed an increase in this practice and thus granted increased autonomy to the child in deciding when to eat, while fathers did not show such a change. Finally, a higher parental BMI predicted a significantly smaller increase in meal atmosphere quality (β = −0.03, t = −2.47, p = 0.01). The results of all regression analyses, significant and non-significant, can be found in Supplementary data.

3.3.4.3. Effects of parental demographics on changes in parental cooking behavior

Regarding parental cooking behaviors, simple regressions indicated that a higher level of education and a more comfortable perceived financial status predicted greater increases in time spent cooking with the child (Table 8 ). However, for level of education, this result became non-significant after adjustment for financial status in a multiple regression model (β = +0.05, t = 1.69, p = 0.09).

Table 8.

Simple linear regression models with changes in cooking behaviors (when change occurred) as dependent variables and parental demographics as independent variables.

| Df | Estimate | Std. Error | t | p | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| More homemade dishes | |||||

| Level of education | 347 | 0.07 | 0.04 | 1.87 | 0.06 |

| No worka[ref working outside] | 346 | 0.16 | 0.12 | 1.41 | 0.16 |

| Working from home [ref working outside] | 346 | 0.18 | 0.12 | 1.50 | 0.13 |

| Financial statusb | 344 | 0.03 | 0.04 | 0.75 | 0.46 |

| Single parent [ref couple] | 347 | −0.20 | 0.13 | −1.51 | 0.13 |

| Parent BMI | 347 | 0.01 | 0.01 | 1.27 | 0.20 |

| Parent sex [ref men] | 347 | 0.03 | 0.09 | 0.32 | 0.75 |

| More time spent cooking with child | |||||

| Level of education | 365 | 0.06 | 0.03 | 2.11 | 0.04c |

| No worka[ref working outside] | 364 | 0.07 | 0.10 | 0.71 | 0.48 |

| Working from home [ref working outside] | 364 | 0.03 | 0.10 | 0.27 | 0.79 |

| Financial statusb | 362 | 0.09 | 0.04 | 2.34 | 0.02d |

| Single parent [ref couple] | 365 | −0.14 | 0.11 | −1.28 | 0.20 |

| Parent BMI | 365 | 0.00 | 0.01 | −0.67 | 0.50 |

| Parent sex [ref men] | 365 | −0.00 | 0.08 | −0.04 | 0.96 |

No work refers to those parents who were at home without work; e.g., those who were technically unemployed due to the lockdown, parents on parental leave, students, etc.

Perceived financial status ranges from less to more comfortable.

No longer significant after adjustment for financial status (multiple regression).

Remains significant after adjustment for level of education (multiple regression).

3.3.4.4. Effects of parental demographics on changes in parental motivations for buying foods

Some parental demographics were also identified as significant predictors of changes in parental motivations for buying foods for their child(ren). Employment status during the lockdown significantly predicted changes in the motivation to buy convenient foods: parents who were working from home (β = −0.54, t = −3.18, p < 0.001) and parents who were at home without work (β = −0.41, t = −2.41, p = 0.02) showed a significant decrease in this motivation, while parents working outside the home showed no significant change in this motivation. In simple regressions, parental level of education (β = −0.11, t = −2.18, p = 0.03) and parent BMI (β = 0.03, t = 2.05, p = 0.04) also significantly predicted changes in the motivation for buying convenient foods. However, in a multiple regression including these three predictors (work status, level of education, parent BMI), only the effect of work status remained significant when adjusted for the effects of these other predictors.

Furthermore, in simple regressions, parents with a higher level of education showed a greater increase in the motivation to buy healthy foods (β = 0.13, t = 3.25, p < 0.001), foods linked to weight control (β = 0.12, t = 2.37, p = 0.02), comforting foods (β = 0.12, t = 2.28, p = 0.02), and sustainable foods (β = 0.17, t = 5.04, p < 0.001) than parents with a lower level of education. In a simple regression model, perceived financial status also significantly predicted changes in the motivation to buy foods related to weight control (β = 0.13, t = 2.08, p = 0.04), but in a multiple regression model, both the effects of level of education and financial status became non-significant after adjustment for each other's effect. Also, in simple regressions, parents with a more comfortable perceived financial status showed a greater increase in the motivation to buy sustainable foods (β = 0.14, t = 3.19, p < 0.001) and single parents showed a smaller increase in this motivation (β = −0.37, t = −2.57, p = 0.01) compared to parents with a less comfortable financial status and parents with a partner. In a multiple regression, level of education and family situation (“single parent”) remained significant predictors for sustainability after adjusting for each other's effects, but not financial status. Finally, parents with a higher BMI showed a smaller increase in the motivation to buy foods that can easily be preserved (“conservation”) (β = −0.04, t = −2.22, p = 0.03). The results of all regression analyses, significant and non-significant, can be found in Supplementary data.

4. Discussion

This study wanted to evaluate possible changes in eating and feeding habits in families with young children during the COVID-19 lockdown in France, versus the period before the lockdown. The results showed that not all, but a majority of parents reported some changes in their child's eating behaviors, in their feeding practices, their food shopping motivations, and in their own eating and cooking behaviors. This clearly indicates that the lockdown had an important impact on families' eating and feeding habits at home.

Children showed significant increases in “food approach” behaviors during the lockdown (behaviors involving a movement toward or a desire for foods: i.e. food enjoyment, emotional overeating, food responsiveness (Vandeweghe, Vervoort, Verbeken, Moens, & Braet, 2016; Webber, Cooke, Hill, & Wardle, 2010)). Children's snack frequency in between meals also increased significantly. Moreover, increases in emotional overeating, food responsiveness and snack frequency were predicted by an increase in child boredom at home: children may have tried to “fill up” their time with eating or found comfort and enjoyment in food during this unusual, monotonous period. In children, the literature related to bored-eating is scarce and the construct is often lumped together in questionnaires with emotional- and stress-eating (e.g., in CDEBQ, CEBQ). In this study, we also studied emotional overeating in a more general way with the CEBQ (four items studying overeating in response to both boredom, anxiety, annoyment, and worry). However, recent studies have indicated that bored-eating is viewed as a distinct construct by mothers, and may be a more common practice in children than emotional- or stress-eating. Therefore, the authors suggested that it may be of interest to present and to study bored-eating separately from other emotions (Hayman et al., 2014, Koball, Meers, Storfer-Isser, Domoff, & Musher-Eizenman, 2012). In adults, boredom has previously been found to increase the desire to eat unhealthily (e.g., Moynihan et al., 2015). Similar to the results in adults, our results showed that increased boredom in children was strongly related to increased food responsiveness, increased emotional overeating and increased snack frequency. Our study thus showed that also in (young) children boredom can play a role in their desire for foods.

Moreover, even though the COVID-19 lockdown was an unusual situation, the increased manifestation of these food approach behaviors and their link with child boredom could be cause for concern. It suggests that these children did not merely rely on their internal cues of hunger and satiety when asking for foods/drinks (crucial for an optimal self-regulation of food intake); and ignoring internal cues could possibly make children overeat and induce weight gain if maintained for a long period (Kral et al., 2012; Monnery-Patris et al., 2019). With age, research has shown that children rely less on their internal cues for their food intake (e.g., Fox, Devaney, Reidy, Razafindrakoto, & Ziegler, 2006). It is therefore important to encourage children (and their caregivers) from a young age to listen to their inner sensations for food intake, and to maintain this even in more challenging situations. Parents and schools could play an important role in guiding children in using adaptive self-regulation strategies and in modeling these strategies. In both children and adults, several types of interventions such as mindfulness-based interventions and appetite awareness training have been proposed to increase awareness of hunger and satiety cues, with various levels of success (e.g., in adults: Alberts, Thewissen, & Raes, 2012; Craighead & Allen, 1995; Kristeller & Wolever, 2010; van de Veer, van Herpen, & van Trijp, 2012; in children: Bloom, Sharpe, Mullan, & Zucker, 2013; Boutelle et al., 2011; Johnson; 2000; Lumeng et al., 2017). Some interventions were for example successful in the short term, but not in the long term (Bloom et al., 2013). Reigh, Rolls, Savage, Johnson, and Keller (2020) recently also suggested a technology-enhanced intervention for preschoolers, using an interactive character-based technology platform and educational materials for parents, to improve preschoolers' energy intake regulation and their knowledge related to hunger, fullness and digestion. In their pilot study, preschoolers' (N = 33) knowledge increased significantly and boys’ short-term energy compensation improved following a 4-week intervention.

The results of our study further showed that when feeding practices were adapted, there was a significant trend to more permissive, child-centered and pleasure-oriented practices: parents reported less rules and limits, more soothing with food and gave more autonomy to the child in deciding when, what, how much and where to eat. Regarding the types of foods offered during snacking, we also observed increased intake of so-called “comfort foods”. The theory of division of autonomy states that parents should be mainly responsible for what, when and where the child eats, but the child for the amount of food eaten (Satter, 1990, Vaughn et al., 2016). Here, we could thus argue that parents may have become a bit too permissive regarding the types of foods offered during the lockdown, there was also a significant decrease in structure of the meals (timing of meals, place). By contrast, the increases in guided choices (i.e., more child autonomy) may indicate that parents had the opportunity to listen better to children's needs and demands, and to respond to them in a more responsive way (even though we are aware that these child demands were not only based on children's internal cues, as discussed above). Interestingly, our results also showed that parental level of stress played a role in changes in parental feeding practices during the lockdown: greater increases in stress predicted greater increases in giving autonomy to the child regarding the amount to eat, and no improvement in meal atmosphere quality (in contrast to parents with no increases in stress).

Furthermore, parents showed many changes in their motivations when buying foods for their children. Greatest increases in motivations were observed for buying pleasurable foods, sustainable foods, natural foods and healthy foods. These findings are in accordance with the findings of a French survey that was carried out by Ipsos during the lockdown in April 2020 for L'Observatoire E. Leclerc des nouvelles consommations: they found that French consumers aged 16–75 years turned more to products of French origin (45%), fresh products (37%) or products from short circuits (37%). Sixty-three percent of consumers claimed that they consumed more local products in order to support the local economy during the lockdown. For the parents in our study, pleasure also became an important motivation, and this is in line with the observed increases in snack frequency in both parents and children, increased emotional eating in both, and the increase in the preparation of comforting foods/recipes during the lockdown. From a cultural point of view, family meals in France were already known to be strongly pleasure-oriented (Lhuissier et al., 2013), and the lockdown seemed to have reinforced this. Convenience became less important for many parents, which can be supported by their reported increase in the preparation of home-cooked meals and their increase in time cooking with their children. Di Renzo et al. (2020) also observed this increase in homemade recipes during the lockdown in Italy.

In the present study, parental motivations for buying foods for their child(ren), changes in parental feeding practices and parental cooking behaviors were significantly predicted by parental characteristics. We observed that especially a higher level of education was linked to some more favorable changes in behaviors: for example, maintaining to eat at set times, buying more sustainable and healthy foods, more cooking with the child, preparing more homemade dishes (marginal effect: p = 0.06). These results may imply that it is of interest to take into account parental level of education when planning interventions to improve parental feeding behaviors. Parents with different levels of education may experience different barriers and facilitators for changing their behaviors. It seems that, during the lockdown, increased time at home could have played a role in facilitating cooking with the child, preparing homemade dishes and buying more local, sustainable foods, but more particularly for parents with higher levels of education. Previous studies have already shown that parental education level is linked to differences in parental feeding practices and in parental motivations when buying foods for their child. For instance, parents with lower levels of education tend to be less concerned by health and more concerned by children's preferences when buying foods (Rigal, Champel, Hébel, & Lahlou, 2019), they serve larger portion sizes (Hébel, 2017; Rigal et al., 2019) and are less likely to restrict their child's intake of unhealthy foods (Wijtzes et al., 2013).

The COVID-19 pandemic has changed our habits in many ways during the lockdown, but even after months, we have not gone back to the situation “before the pandemic”. As we are still reshaping some of our habits, we suggest that future research and policy makers also focus on the implications for the food domain in all its facets, this by also taking into account possible facilitators and barriers linked to people's socio-demographic characteristics.

We acknowledge that there were several limitations to this study. First, parental practices and behaviors were self-reported in this study and may be subject to social desirability bias even though the questionnaires were anonymous. The children's eating behaviors and level of boredom were also parent-reported and thus reflected the parent's perception. Second, the data obtained about the period before the lockdown was reported retrospectively, possibly leading to a recall bias that can threaten the internal validity of our study (Delgado Rodriguez and Llorca, 2014, Hassan, 2006). Yet, recall accuracy diminishes with increasing time gap, and as the time gap in this study was very small (max. eight weeks), we think the recall bias was limited here. Here, we also want to note that we did not define “the period before the lockdown” for the parents. It is therefore possible that parents interpreted this period in different ways (more or less broad) and thus responded differently based on their own interpretation, with possible corresponding effects on our results. We hope, however, that the differential interpretations would be limited because of the high contrast between the two periods parents needed to report on: the “normal” life and related general habits right before the lockdown versus those during the lockdown.

Meanwhile, this study also has several strengths. To our knowledge, it is the only study that looked in a more systemic way at changes in families' food habits during the COVID-19 lockdown, including eating and cooking behaviors, parental feeding practices and parental motivations when buying foods for the family. Other studies tend to focus uniquely on adults or on children. Our sample may not be entirely representative of the national population in France: there was for example a relatively small sample of parents with a low level of education (33.5% in our sample compared to approximately 55% in the French population (Insee, 2016, pp. 1–256)), and the majority of our participants were female (71.7%). However, we managed to recruit parents with diverse profiles, also in terms of work status, perceived financial situation, relationship status, and BMI categories (of both children and adults) that were very close to representativeness in the French population (Argouarc'h & Picard, 2018; Verdot, Torres, Salanave, Deschamps, 2017). This enabled us to obtain a broad idea of the changes in eating and feeding habits in young children and their parents in France, and of the parental characteristics that were linked to these changes.

5. Conclusion and perspectives

This study provided unique insights into how a drastic change in habits is accompanied by changes in eating and feeding habits both on parent and child level. The unusual situation drove some parents to turn a blind eye to the usual feeding rules, and to privilege enjoyment and comfort at home. Changes in child boredom and parental stress were found to influence eating and feeding behaviors, and some parental characteristics were identified as possible barriers and facilitators for eating, feeding and cooking behaviors. These insights could be useful for future studies and interventions, and could be of interest to policy makers. Qualitative studies that reflect the experiences of parents and children during the lockdown could also be interesting to complement our results. They could provide us, for example, with more insights into reasons why eating behaviors, feeding practices and food shopping motivations have changed or not, and if the lockdown and the accompanying changes have had an impact on families’ food habits on a longer term and why.

Authors contributions

KP, SI and SM-P conceptualized the study. KP and CC conducted all analyses. KP wrote a first version of the manuscript, thereafter all authors contributed to editing the manuscript and they all approved the final article.

Funding sources

This work was supported by the European Union's horizon 2020 research and innovation program (Marie Sklodowska-Curie grant agreement No 764985: EDULIA project); and by a grant from the Conseil Régional Bourgogne, Franche-Comte (PARI grant).

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank the independent ethical committee Inserm for accepting to review their study protocol in a very limited time span. They also thank the participants for their interest in the study.

Footnotes

Supplementary data to this article can be found online at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.appet.2021.105132.

Appendix A. Supplementary data

The following are the Supplementary data to this article:

References

- Alberts H.J., Thewissen R., Raes L. Dealing with problematic eating behaviour. The effects of a mindfulness-based intervention on eating behaviour, food cravings, dichotomous thinking and body image concern. Appetite. 2012;58(3):847–851. doi: 10.1016/j.appet.2012.01.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Anses . Maisons-Alfort: Agence Nationale de Sécurité Sanitaire de l'Alimentation, de l'Environnement et du Travail (ANSES); 2017. Troisième étude individuelle nationale des consommations alimentaires (Etude INCA3). Actualisation de la base de données des consommations alimentaires et de l’estimation des apports nutritionnels des individus vivant en France.https://www.anses.fr/ Retrieved from. [Google Scholar]

- Argouarc’h J., Picard S. Les niveaux de vie en 2016. La prime d’activité soutients l’évolution du niveau de vie des plus modestes. Insee Première. 2018;1710:1–4. https://www.insee.fr/ Retrieved from. [Google Scholar]

- Baughcum A.E., Powers S.W., Johnson S.B., Chamberlin L.A., Deeks C.M., Jain A., et al. Maternal feeding practices and beliefs and their relationships to overweight in early childhood. Journal of Developmental and Behavioral Pediatrics. 2001;22(6):391–408. doi: 10.1097/00004703-200112000-00007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Birch L.L. Development of food preferences. Annual Review of Nutrition. 1999;19(1):41–62. doi: 10.1146/annurev.nutr.19.1.41. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bloom T., Sharpe L., Mullan B., Zucker N. A pilot evaluation of appetite‐awareness training in the treatment of childhood overweight and obesity: A preliminary investigation. International Journal of Eating Disorders. 2013;46(1):47–51. doi: 10.1542/peds.106.6.1429. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bollen K.A. A new incremental fit index for general structural equation models. Sociological Methods & Research. 1989;17(3):303–316. doi: 10.1177/0049124189017003004. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Boutelle K.N., Peterson C.B., Rydell S.A., Zucker N.L., Cafri G., Harnack L. Two novel treatments to reduce overeating in overweight children: A randomized controlled trial. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 2011;79(6):759–771. doi: 10.1037/a0025713. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Craighead L.W., Allen H.N. Appetite awareness training: A cognitive behavioral intervention for binge eating. Cognitive and Behavioral Practice. 1995;2(2):249–270. doi: 10.1016/S1077-7229(95)80013-1. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Delgado-Rodriguez M., Llorca J. Bias. Journal of Epidemiological Community Health. 2014;58:635–641. doi: 10.1136/jech.2003.008466. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Di Renzo L., Gualtieri P., Pivari F., Soldati L., Attinà A., Cinelli G., et al. Eating habits and lifestyle changes during COVID-19 lockdown: An Italian survey. Journal of Translational Medicine. 2020;18:229. doi: 10.1186/s12967-020-02399-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Evers C., Dingemans A., Junghans A.F., Boevé A. Feeling bad or feeling good, does emotion affect your consumption of food? A meta-analysis of the experimental evidence. Neuroscience & Biobehavioral Reviews. 2018;92:195–208. doi: 10.1016/j.neubiorev.2018.05.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fox M.K., Devaney B., Reidy K., Razafindrakoto C., Ziegler P. Relationship between portion size and energy intake among infants and toddlers: Evidence of self-regulation. Journal of the American Dietetic Association. 2006;106(Suppl. 1):77–83. doi: 10.1016/j.jada.2005.09.039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Francou A., Hébel P. Consommation et Modes de Vie; 2017. Le goûter en perte de vitesse et loin des recommandations.http://www.credoc.fr/ Retrieved from. [Google Scholar]

- Hassan E. Recall bias can be a threat to retrospective and prospective research designs. The Internet Journal of Epidemiology. 2006;3(2):339–412. [Google Scholar]

- Hayman L.W., Jr., Lee H.J., Miller A.L., Lumeng J.C. Low-income women's conceptualizations of emotional-and stress-eating. Appetite. 2014;83:269–276. doi: 10.1016/j.appet.2014.09.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hébel P. Journées Francophones de Nutrition; Nantes, France: 2017. Nouvelles données sur les déterminants des quantités consommées. [Google Scholar]

- Insee . édition 2016. 2016, November 22. France, portrait social, édition 2016. Insee Références.https://www.insee.fr/ Retrieved from. [Google Scholar]

- Jiao W.Y., Wang L.N., Liu J., Fang S.F., Jiao F.Y., Pettoello-Mantovani M., et al. Behavioral and emotional disorders in children during the COVID-19 epidemic. The Journal of Pediatrics. 2020;221:264–266. doi: 10.1016/j.jpeds.2020.03.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnson S.L. Improving preschoolers' self-regulation of energy intake. Pediatrics. 2000;106(6):1429–1435. doi: 10.1002/eat.22041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaur H., Li C., Nazir N., Choi W.S., Resnicow K., Birch L.L., et al. Confirmatory factor analysis of the child-feeding questionnaire among parents of adolescents. Appetite. 2006;47(1):36–45. doi: 10.1016/j.appet.2006.01.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koball A.M., Meers M.R., Storfer-Isser A., Domoff S.E., Musher-Eizenman D.R. Eating when bored: Revision of the Emotional Eating Scale with a focus on boredom. Health Psychology. 2012;31(4):521–524. doi: 10.1037/a0025893. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kral T.V., Allison D.B., Birch L.L., Stallings V.A., Moore R.H., Faith M.S. Caloric compensation and eating in the absence of hunger in 5-to 12-y-old weight-discordant siblings. American Journal of Clinical Nutrition. 2012;96(3):574–583. doi: 10.3945/ajcn.112.037952. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kristeller J.L., Wolever R.Q. Mindfulness-based eating awareness training for treating binge eating disorder: The conceptual foundation. Eating Disorders. 2010;19(1):49–61. doi: 10.1080/10640266.2011.533605. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lhuissier A., Tichit C., Caillavet F., Cardon P., Masullo A., Martin-Fernandez J., et al. Who still eats three meals a day? Findings from a quantitative survey in the paris area. Appetite. 2013;63:59–69. doi: 10.1016/j.appet.2012.12.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Loopstra R. Vulnerability to food insecurity since the COVID-19 lockdown. 2020, April 14. https://foodfoundation.org.uk/publication/vulnerability-to-food-insecurity-since-the-covid-19-lockdown/ Retrieved from.

- Lumeng J.C., Miller A.L., Horodynski M.A., Brophy-Herb H.E., Contreras D., Lee H.…Peterson K.E. Improving self-regulation for obesity prevention in head start: A randomized controlled trial. Pediatrics. 2017;139(5) doi: 10.1542/peds.2016-2047. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- L'Observatoire E.Leclerc des Nouvelles Consommations COVID-19 et consommation : 57% des Français accordent davantage d’importance au prix [press release] 2020, May 6. https://nouvellesconso.leclerc/wp-content/uploads/2020/05/Communique%CC%81-de-presse_OBSERVATOIRE-E.Leclerc-060520.pdf

- Marty L., de Lauzon-Guillain B., Labesse M., Nicklaus S. Food choice motives and the nutritional quality of diet during the COVID-19 lockdown in France. Appetite. 2021;157:105005. doi: 10.1016/j.appet.2020.105005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Michels N., Sioen I., Braet C., Eiben G., Hebestreit A., Huybrechts I., et al. Stress, emotional eating behaviour and dietary patterns in children. Appetite. 2012;59(3):762–769. doi: 10.1016/j.appet.2012.08.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Monnery-Patris S., Rigal N., Peteuil A., Chabanet C., Issanchou S. Development of a new questionnaire to assess the links between children's self-regulation of eating and related parental feeding practices. Appetite. 2019;138:174–183. doi: 10.1016/j.appet.2019.03.029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moynihan A.B., Van Tilburg W.A., Igou E.R., Wisman A., Donnelly A.E., Mulcaire J.B. Eaten up by boredom: Consuming food to escape awareness of the bored self. Frontiers in Psychology. 2015;6:369. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2015.00369. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- de Onis M., Onyango A.W., Borghi E., Siyam A., Nishida C., Siekmann J. Development of a WHO growth reference for school-aged children and adolescents. Bulletin of the World Health Organization. 2007;85:660–667. doi: 10.2471/blt.07.043497. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pietrobelli A., Pecoraro L., Ferruzzi A., Heo M., Faith M., Zoller T., et al. Effects of COVID‐19 lockdown on lifestyle behaviors in children with obesity living in verona, Italy: A longitudinal study. Obesity. 2020 doi: 10.1002/oby.22861. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Poti J.M., Popkin B.M. Trends in energy intake among US children by eating location and food source, 1977-2006. Journal of the American Dietetic Association. 2011;111(8):1156–1164. doi: 10.1016/j.jada.2011.05.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- R Core Team . R Foundation for Statistical Computing; Vienna, Austria: 2019. R: A language and environment for statistical computing.https://www.R-project.org/ Retrieved from. [Google Scholar]

- Reigh N.A., Rolls B.J., Savage J.S., Johnson S.L., Keller K.L. Development and preliminary testing of a technology-enhanced intervention to improve energy intake regulation in children. Appetite. 2020;155:104830. doi: 10.1016/j.appet.2020.104830. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rigal N., Chabanet C., Issanchou S., Monnery-Patris S. Links between maternal feeding practices and children's eating difficulties. Validation of French tools. Appetite. 2012;58(2):629–637. doi: 10.1016/j.appet.2011.12.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rigal N., Champel C., Hébel P., Lahlou S. Food portion at ages 8–11 and obesogeny: The amount of food given to children varies with the mother's education and the child's appetite arousal. Social Science & Medicine. 2019;228:111–116. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2019.03.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rodríguez-Martín B.C., Meule A. Food craving: New contributions on its assessment, moderators, and consequences. Frontiers in Psychology. 2015;6:21. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2015.00021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Satter E. The feeding relationship: Problems and interventions. The Journal of Pediatrics. 1990;117(2):S181–S189. doi: 10.1016/S0022-3476(05)80017-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vandeweghe L., Vervoort L., Verbeken S., Moens E., Braet C. Food approach and food avoidance in young children: Relation with reward sensitivity and punishment sensitivity. Frontiers in Psychology. 2016;7:928. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2016.00928. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vaughn A.E., Dearth-Wesley T., Tabak R.G., Bryant M., Ward D.S. Development of a comprehensive assessment of food parenting practices: The home self-administered tool for environmental assessment of activity and diet family food practices survey. Journal of the Academy of Nutrition and Dietetics. 2017;117(2):214–227. doi: 10.1016/j.jand.2016.07.021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vaughn A.E., Ward D.S., Fisher J.O., Faith M.S., Hughes S.O., Kremers S.P., et al. Fundamental constructs in food parenting practices: A content map to guide future research. Nutrition Reviews. 2016;74(2):98–117. doi: 10.1093/nutrit/nuv061. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van de Veer E., van Herpen E., van Trijp H. Body and mind: How mindfulness enhances consumers' responsiveness to physiological cues in food consumption. Advances in Consumer Research. 2012;39:603–604. [Google Scholar]

- Ventura A.K., Birch L.L. Does parenting affect children's eating and weight status? International Journal of Behavioral Nutrition and Physical Activity. 2008;5(1):1–12. doi: 10.1186/1479-5868-5-15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Verdot C., Torres M., Salavane B., Deschamps V. 2017. Children and adults body mass index in France in 2015. Results of the Esteban Study and trends since 2006. Bulletin épidémiologique hebdomadaire H8; pp. 234–241.http://invs.santepubliquefrance.fr/ Retrieved from. [Google Scholar]

- Wang C., Pan R., Wan X., Tan Y., Xu L., Ho C.S., et al. Immediate psychological responses and associated factors during the initial stage of the 2019 coronavirus disease (COVID-19) epidemic among the general population in China. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2020;17(5):1729. doi: 10.3390/ijerph17051729. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wardle J., Guthrie C.A., Sanderson S., Rapoport L. Development of the children's eating behaviour questionnaire. The Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry and Allied Disciplines. 2001;42(7):963–970. doi: 10.1017/S0021963001007727. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Webber L., Cooke L., Hill C., Wardle J. Associations between children's appetitive traits and maternal feeding practices. Journal of the American Dietetic Association. 2010;110(11):1718–1722. doi: 10.1016/j.jada.2010.08.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- WHO The WHO child growth standards website. 2006. http://www.who.int/ Retrieved from.

- Wijtzes A.I., Jansen W., Jansen P.W., Jaddoe V.W., Hofman A., Raat H. Maternal educational level and preschool children's consumption of high-calorie snacks and sugar-containing beverages: Mediation by the family food environment. Preventive Medicine. 2013;57:607–612. doi: 10.1016/j.ypmed.2013.08.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.