Abstract

The current COVID-19 pandemic caused by SARS-CoV-2 coronavirus is expanding around the globe. Hence, accurate and cheap portable sensors are crucially important for the clinical diagnosis of COVID-19. Molecularly imprinted polymers (MIPs) as robust synthetic molecular recognition materials with antibody-like ability to bind and discriminate between molecules can perfectly serve in building selective elements in such sensors. Herein, we report for the first time on the development of a MIP-based electrochemical sensor for detection of SARS-CoV-2 nucleoprotein (ncovNP). A key element of the sensor is a disposable sensor chip - thin film electrode - interfaced with a MIP-endowed selectivity for ncovNP and connected with a portable potentiostat. The resulting ncovNP sensor showed a linear response to ncovNP in the lysis buffer up to 111 fM with a detection and quantification limit of 15 fM and 50 fM, respectively. Notably, the sensor was capable of signaling ncovNP presence in nasopharyngeal swab samples of COVID-19 positive patients. The presented strategy unlocks a new route for the development of rapid COVID-19 diagnostic tools.

Keywords: Molecularly imprinted polymer, Electrochemical sensor, SARS-CoV-2 nucleoprotein, COVID-19 antigen test

Graphical abstract

1. Introduction

The ongoing outbreak of COVID-19 experienced around the globe was discovered in December 2019 in Wuhan, China (Zhou et al., 2020). WHO officially declared it a pandemic on 12th March 2020 (World Health Organization, 2020). The primary symptoms of COVID-19 infection are fever, coughing, shortness in breathing, etc. However, in some cases, patients may be asymptomatic, with no coughing, and fever or have mild symptoms. These asymptomatic patients have the greater potential to spread the disease quickly to other people. Therefore, to trace and diagnose COVID-19 patients, rapid and accurate COVID-19 carriers' screening is of crucial importance for the prevention of spreading the virus at the early stages.

Severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2) belongs to the enveloped, positive-stranded RNA virus family. SARS-CoV-2 has four major structural proteins: spike, membrane, envelope, and nucleocapsid. The SARS-CoV-2 nucleocapsid protein (ncovNP) is responsible for packaging and protecting coronavirus genomic RNA. The high abundance and immunogenicity of ncovNP make it a suitable antigen for the development of COVID-19 diagnostic tests (Diao et al., 2020). Thus, for example, the high diagnostic value of serum ncovNP in the early-stage of infection was confirmed by ELISA double antibody sandwich assay (Li et al., 2020).

Today, the reverse transcription polymerase chain reaction (RT-PCR) is one of the most accurate laboratory methods for detecting SARS-CoV-2 from the nasopharyngeal swab of patients and is used for routine diagnosis of COVID-19 in many laboratories worldwide (Lai et al., 2020). However, RT-PCR tests require expensive instrumentation and skilled personnel, have a long turnaround time and complex protocols as well as being prone to the false-negative results. Apart from that, ELISA methods have also been developed for SARS-CoV-2 antibodies testing in serum (EUA, 2020; Rump et al., 2021). Although the serological tests are cheaper and have shorter analysis time as compared to PCR tests but they are not suitable for the diagnosis at early-stage of infection, since the detectable level of antibodies is produced at 10–14 days after the onset of the symptoms and can therefore be used mainly for serological screening and epidemiological studies (Liu et al., 2020). Therefore, there is still a crucial demand for cheaper and portable biosensing devices to facilitate rapid testing for COVID-19. Recently, different testing technologies for rapid detection of a SARS-CoV-2 specific antigen (a viral protein) have been developed and some of them are already commercially available (FIND, 2020. SARS-CoV-2 diagnostic pipeline. 2020,” n.d.). Thus, Porte, L. et al. reported on the development of rapid SARS-CoV-2 antigen test based on fluorescence immunochromatographic assay (Porte et al., 2020). Seo et al. reported a field-effect transistor (FET)-based biosensing device for detecting SARS-CoV-2 spike protein in clinical samples (Seo et al., 2020). Up to date a number of SARS-CoV-2 antigen diagnostics tests have received the Emergency use authorization from FDA (FDA, 2020). However, most of these diagnostic tools rely on biological recognition elements, i.e diagnostic antibodies that ensure the selectivity of the device towards the target but reduce sensor shelf life and increase the cost.

Various approaches have been investigated to replace these biological receptors with artificial analogues. One of the promising approaches is the use of molecularly imprinted polymers (MIPs) - materials with antibody-like ability to bind and discriminate between molecules. Molecular imprinting can be defined as the process of template-induced formation of specific molecular recognition sites in the polymer material. In this process, a mixture of functional monomers is polymerized around a chosen target acting as a template. The subsequent removal of the templates from the formed polymer leaves behind binding sites that are complementary to the target molecule in size, shape and arrangement of functional groups and are thus capable of selectively recognizing these molecules. The main benefits of MIPs as synthetic receptors are excellent chemical and thermal stability coupled with their reproducible and cost-effective fabrication (Haupt and Mosbach, 2000; Zhao et al., 2019). The robust integration of a MIP with a sensor platform capable of responding upon interaction between MIP and a binding analyte is a key aspect in the design of a MIP-based sensor. Electrosynthesis was shown to be a convenient approach for the facile and effective interfacing of protein-MIPs with sensor transducers allowing rapid and controlled deposition of polymer films with tunable thickness (Erdőssy et al., 2016; Sharma et al., 2012).

MIPs integrated with different sensing platforms have been studied extensively in recent decades for detection of various disease biomarkers such as epithelial ovarian cancer antigen (Viswanathan et al., 2012), cancer biomarker-prostate specific antigen (Jolly et al., 2016), cancer tumor marker CA 15-3 (Wang et al., 2010), myoglobin (Shumyantseva et al., 2016), and cardiac troponin T (Silva et al., 2016). Our group recently reported on the development of MIP-based sensors for the detection of neurotrophic factor proteins such as BDNF and CDNF as the potential biomarkers of the neurodegenerative diseases (Kidakova et al, 2019, 2020). Furthermore, MIP-based sensors have also been investigated for the detection of viral proteins such as bovine leukemia virus glycoprotein gp51 (Ramanaviciene and Ramanavicius, 2004), dengue virus NS1 protein (Tai et al., 2005), glycoprotein of HIV type 1 (Lu et al., 2012). However, to date, according to our knowledge, the detection of ncovNP by a MIP-based sensor has never been reported in the literature.

Combination of MIPs and electrochemical methods represents a valuable approach to the development of low cost, sensitive, fast and portable sensing systems (Scheller et al., 2019). The detection principle of these sensors is mostly based on monitoring the charge transfer carried by a redox probe through a thin MIP film (Sharma et al., 2019).

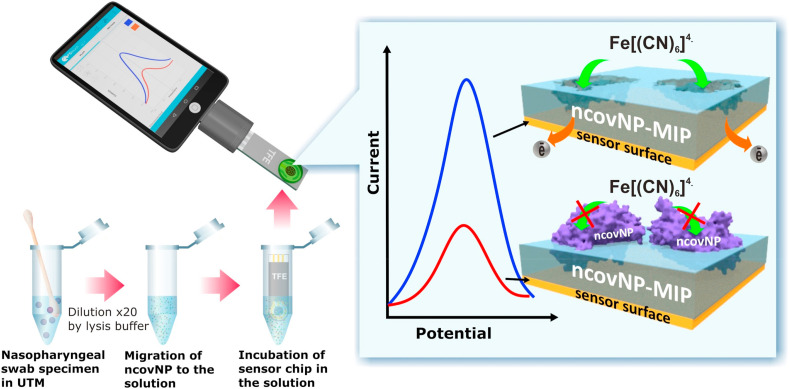

Herein, we report for the first time on the development of a MIP-based electrochemical ncovNP sensor (Fig. 1 ). A key element of the sensor is a disposable sensor chip - thin film electrode (TFE) - interfaced with a MIP-endowed selectivity for ncovNP (ncovNP-MIP). The chip was connected with a portable potentiostat and the capability of such a sensor system to selectively recognize the target analyte (ncovNP) was studied through differential pulse voltammetry (DPV) in the presence of a redox pair. The clinical diagnostic feasibility of ncovNP sensor was studied by analyzing the nasopharyngeal swab specimens of patients.

Fig. 1.

COVID-19 diagnostics principle by nconNP sensor analyzing the samples prepared from nasopharyngeal swab specimens of patients.

2. Experimental

2.1. Material and method

4-aminothiophenol (4-ATP), 2-mercaptoethanol (2-ME), m-phenylenediamine (mPD), bovine serum albumin (BSA), sodium dihydrogen phosphate dihydrate, disodium hydrogen phosphate, and sodium dodecyl sulfate were obtained from Sigma-Aldrich. Ethanol 96% was purchased from Estonian Spirit OÜ (Estonia). SARS-Cov-2 nucleoprotein (ncovNP), a subunit of SARS-Cov-2 spike protein (S1) and Cluster of Differentiation 48 (CD48) protein were provided by Icosagen AS (Estonia). Hepatitis C virus (HCV) surface viral antigen (E2) was obtained from the Institute of Macromolecular Compounds of the Russian Academy of Sciences. 3,3′-dithiobis [sulfosuccinimidyl propionate] (DTSSP) and Triton X-100 were purchased from Thermo Fisher Scientific Inc., sulfuric acid, hydrogen peroxide, potassium chloride (KCl), and acetic acid were purchased from Lach-ner, S.R.O. Sodium chloride (NaCl), Tris EDTA buffer concentrate, and ethylenediaminetetraacetic acid (EDTA) were obtained from Fluka analytical. Potassium ferricyanide and ferrocyanide were purchased from Riedel-de Haen. MicruX™ gold-based thin-film electrodes (Au-TFE) were purchased from Micrux Technologies (Spain). All chemicals were of analytical grade and were used as received without any further purification. Ultrapure Milli-Q water (resistivity 18.2 MΩ cm at 25 °C, EMD Millipore) was used for the preparation of all aqueous solutions.

2.2. Sensor fabrication

The ncovNP sensor was prepared by modification of Au-TFE with ncovNP-MIP film generated from poly-m-phenylenediamine (PmPD). m-Phenylenediamine as a suitable functional monomer was rationally selected by a computational modeling approach (Boroznjak et al., 2017) (see section S1 in SI for details). The protocol for synthesis of ncovNP-MIP was adapted from our previous work (Tretjakov et al., 2016). Before modification, Au-TFE was cleaned with a cold piranha solution (H2SO4:H2O2, 3:1) for 2 min, then rinsed with double distilled water and dried under a nitrogen atmosphere. The WE of the Au-TFE was modified with 4-ATP by incubating it in 100 mM 4-ATP ethanolic solution for 30 min and vortex for 5 min in ethanol to remove the non-bound 4-ATP. The cleavable linker monolayer was generated by the covalent attachment of DTSSP to 4-ATP/Au-TFE via drop casting of 4 μL (10 mM) DTSSP solution in phosphate buffered saline (PBS) for 30 min and washed with PBS. For ncovNP immobilization, 4 μL of PBS containing 0.55 μM of ncovNP was dropped on the cleavable linker modified electrode for 30 min and washed with plenty of PBS.

The synthesis of PmPD on ncovNP-modified Au-TFE was performed in the electrochemical cell (ED-AIO-Cell, Micrux Technologies, Spain) connected with the electrochemical workstation (Reference 600TM, Gamry Instruments, USA). PmPD film was electrodeposited from PBS containing 10 mM mPD at 0.6 V vs Ag/AgCl/KCl with an optimized charge density. Molecular imprints of ncovNP in the polymer film were generated by treating the polymer film with ethanolic solution of 0.1 M 2-ME to cleave the S–S bond of DTSSP and facilitate the release of ncovNP, followed by washing with a 10% acetic acid solution. A similar procedure was also adopted for the reference film, non-imprinted polymers (NIPs), with the exception of treating with 2-ME to save the covalent attachment of ncovNP in the polymer matrix in NIPs and to avoid formation of the molecular imprints of ncovNP in this film.

The sensor preparation steps were characterized by cyclic voltammetry (CV) in potential range of −0.2 to 0.2 at a scan rate of 100 mV/s. Cyclic voltammetry was conducted in 1 M KCl solution containing 4 mM redox probe K3[Fe(CN)6]/K4[Fe(CN)6].

2.3. Evaluation of the sensor performance

All the samples were prepared in a lysis buffer (LB) (pH = 7.2) containing 27.5 mM of Tris-HCl, 12.5 mM of EDTA, 1.5% (v/v) of Triton X-100, and 0.1% SDS diluted with MQ water to the desired volume and stored at 4 °C. The LB did not contain a strong chaotropic agent such as guanidinium chloride in order to minimally affect the native conformations of ncovNP.

The rebinding of ncovNP on the prepared ncovNP sensors was measured by means of DPV. The measurements were performed in the potential range of −0.2 to 0.2 V with the pulse amplitude of 0.025 V, pulse time of 0.025 s, step potential of 0.005 V and scan rate 0.1 V/s in 1 M KCl solution containing 4 mM redox probe K3[Fe(CN)6]/K4[Fe(CN)6] at room temperature. The response (I n) of the sensor was calculated as follows:

| In= (I0–I)/I0 | (1) |

where I 0 and I represent the DPV anodic peak currents measured after incubation in sample solutions without and with the target analyte (ncov-NP), respectively.

The thickness of ncovNP-MIP and incubation time in the sample solution were optimized (see section S2). Further, the ncovNP sensors with the optimized parameters were used to determine their analytical performance in prepared and clinical sample solutions.

The selectivity of the sensor was assessed by comparing the responses against the target (ncovNP) and interfering analytes (S1, BSA, E2 HCV, and CD48) at equivalent concentrations.

Limit of Detection (LOD), and Limit of Quantitation (LOQ) of the sensors were derived from linear regression of I n obtained in LB and COVID-19-negative clinical samples (see below) containing the known concentration of ncovNP:

| LOD = 3∙SD/b | (2) |

| LOQ = 10∙SD/b | (3) |

where SD and b represents the standard deviation and the slope of the regression line, respectively.

The clinical samples as solutions of nasopharyngeal specimens vortexed in UTM (universal transport medium) from four COVID-19 negative and four COVID-19 positive patients were obtained from the SYNLAB Eesti medical laboratory (Estonia). The presence or absence of the viral infection in the clinical samples was confirmed with RT-PCR method. Before testing the samples by ncovNP sensor they were vortexed for 30 min in LB to facilitate the viral protein release as well as to decrease (20 fold) the concentration of interfering species present in UTM. The LB-diluted samples from four COVID-19-negative patients were additionally spiked with ncovNP at a concentration range of 22.2–333 fM and used to construct the calibration plot and derive LOD and LOQ values. Reading DPV signals from ncovNP sensors was performed by portable potentiostats (EmStat3 Blue and Sensit Smart, PalmSens BV, The Netherlands).

3. Results and discussion

3.1. Operational principle of ncovNP sensor

A key element of the electrochemical sensor is a disposable Au-TFE chip modified with ncovNP-MIP as a recognition element and connected with the portable potentiostat that is controlled by a software in a tablet computer or mobile phone (Fig. 1). The potentiostat measures the reduction in the intensity of the charge transfer carried by [Fe(CN)6]3-/[Fe(CN)6]4- redox probe through the thin ncovNP-MIP film to the Au-TFE. If the film has rebound its macromolecular target (ncovNP) after incubation of the sensor chip in a sample solution, the charge transfer is efficiently hindered causing a current decrease that correlates with the concentration of the virus protein in the sample.

3.2. Preparation and optimization of ncovNP sensor

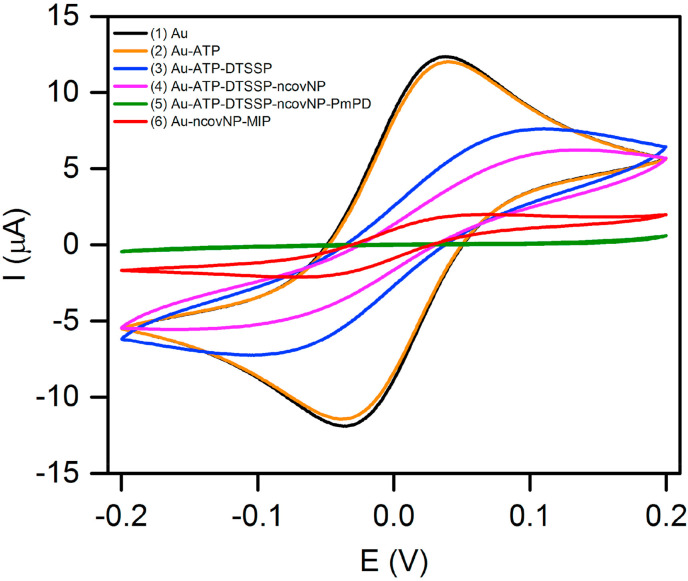

The ncovNP-MIP synthesis strategy is based on the electrochemical surface imprinting approach developed in our earlier study and successfully used to imprint various proteins (Kidakova et al., 2020; Tretjakov et al, 2013, 2016). All the fabrication steps were monitored by CV measurements (Fig. 2 ). It can be seen that while the modification of Au-TFE by 4-ATP monolayer almost did not affect anodic/cathodic current peaks of the redox couple indicating that this short thiol was too thin to effectively block electron transfer happening on the electrode surface, on the other hand, after the subsequent attachment ncovNP via DTSSP, the redox current peaks were significantly reduced. Nevertheless, it was still possible to initiate PmPD growth at a rather low potential (0.6 V vs Ag/AgCl/KCl) comparable with that at which the similar reaction happens at a bare Au-electrode (Fig. S3). The redox peaks completely disappeared after PmPD electrodeposition indicating non-conducting polymer film formation. However, the treatment of the modified electrode in mercaptoethanol and acetic acid caused a prominent increase in the peak current indicating supposedly, elution of ncovNP from the PmPD matrix and formation of molecular imprints, which tunneled the charge transfer across the ultra-thin non-conducting PmPD layer to the electrode.

Fig. 2.

Cyclic voltammograms recorded in 1 M KCl solution containing a 4 mM redox probe K3[Fe(CN)6]/K4[Fe(CN)6] on bare Au (1), and after the subsequent fabrication steps of ncovNP-MIP: modification by 4-ATP (2), DTSSP (3), and ncovNP (4), electrodeposition of PmPD (5) and treatment in 2-ME and acetic acid (6) (see section 2.3 for details).

Since the present imprinting approach allows the generation of macromolecular imprints situated at/or close to the polymer film surface, the deposition of polymer with an appropriate film thickness is of crucial importance in order to avoid irreversible entrapment of a protein and infeasibility of its removal during the subsequent washing out procedure. Another reason to optimize the thickness of PmPD is to provide sufficient charge transfer through the molecular imprints to the electrode for following responsive sensing of protein rebinding on the ncovNP-MIPs. It was found that PmPD film deposited by 2 mC/cm2 was optimal for ncovNP sensor preparation (see section S2 for details). Apparently, with this charge, the polymer generated at the surface of electrode confines the anchored ncovNPs, but does not hinder their successful extraction during ncovNP washing procedure. Thus, the resulting polymer is endowed with the ncovNP-selective imprints efficiently transducing the binding events of ncovNP.

Rebinding time of ncovNP at the surface of ncovNP sensor was another parameter that was optimized. The sensor response became saturated and reached equilibrium after 15 min incubation in the ncovNP containing sample (Fig. S5b). Therefore, 15 min was selected as the optimal time to rebind ncovNP at the surface of ncovNP sensor.

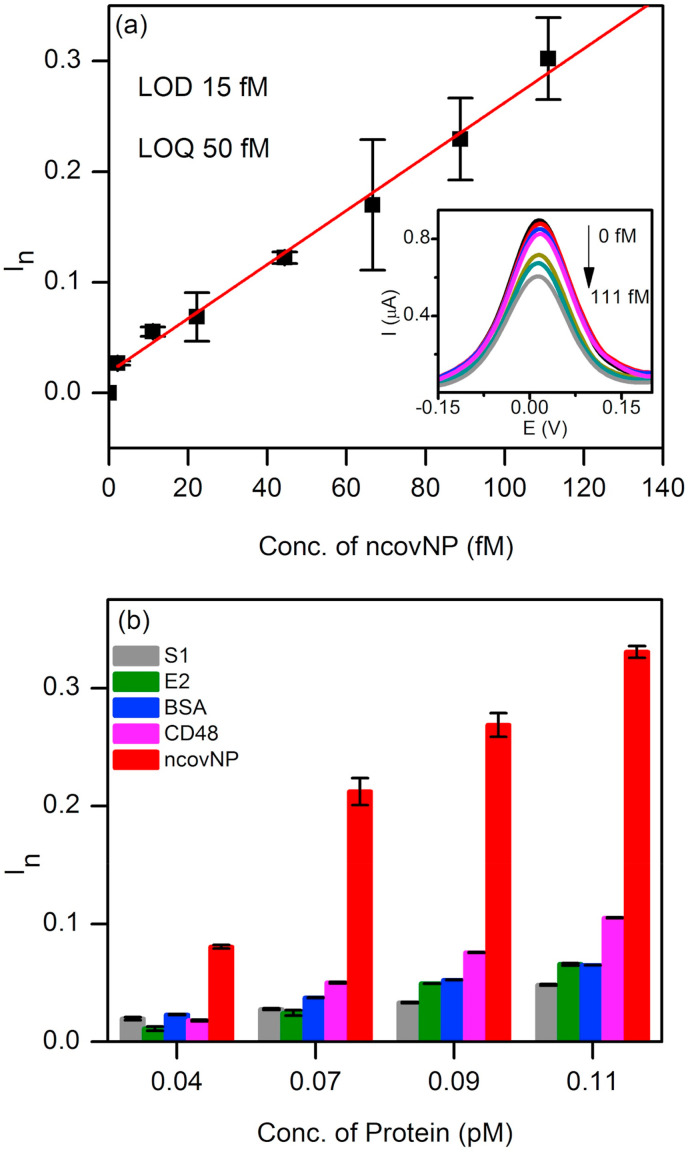

3.3. Performance of the sensor in ncovNP spiked lysis buffer

The calibration plot of ncovNP sensor against ncovNP in LB depicts the pseudo-linear increase of the sensor response with ncovNP concentration up to 111 fM (Fig. 3 a). The calculated LOD and LOQ values were 15 and 50 fM (0.7–2.2 pg/mL), respectively that fell well within the range of ncovNP level present in real samples of COVID-19 patients (Bar-On et al., 2020; Li et al., 2020; Pan et al., 2020).

Fig. 3.

(a) Calibration plot of ncovNP sensor obtained at the low concentration range of ncovNP (2–111 fM) in LB. The inset shows typical DPV curves used to construct the calibration plot. (b) Selectivity test of ncovNP sensor showing its responses against the different proteins (S1, E2 HCV, BSA, CD48 and ncovNP) applied at concentrations (0.04, 0.07, 0.09, and 0.11 pM) in LB.

The selectivity of the ncovNP sensor for ncovNP was explored by evaluating its ability to discriminate between target and interfering proteins such as S1 (75 kDa, pI 6.0), E2 HCV (47 kDa, pI 8.2), CD48 (22 kDa, pI 9.3), and BSA (66 kDa, pI 4.7). The selection of these proteins was based on the size, isoelectric point, molecular weight, and possible presence in real samples. Thus, CD48 was selected due to its close isoelectric point and smaller molecular mass, E2 HCV - as a protein having molecular weight close to ncovNP, S1, being a subunit of SARS-CoV-2 spike protein, can be present in the real clinical samples along with ncovNP. As it can be seen, the response of ncovNP sensor was considerably higher against ncovNP as compared to the responses against the interfering proteins demonstrating thus the appreciable selectivity of the fabricated device towards ncovNP (Fig. 3b) and promising uncompromised performance in clinical samples. Moreover, the ability of the sensor to discriminate between ncovNP and CD48, the protein with smaller size and close pI, provided additional evidence that the molecular cavities in ncovNP-MIP were complementary to ncovNP not only in size but also in arrangement of the functional groups (see Section S1, Fig. S1).

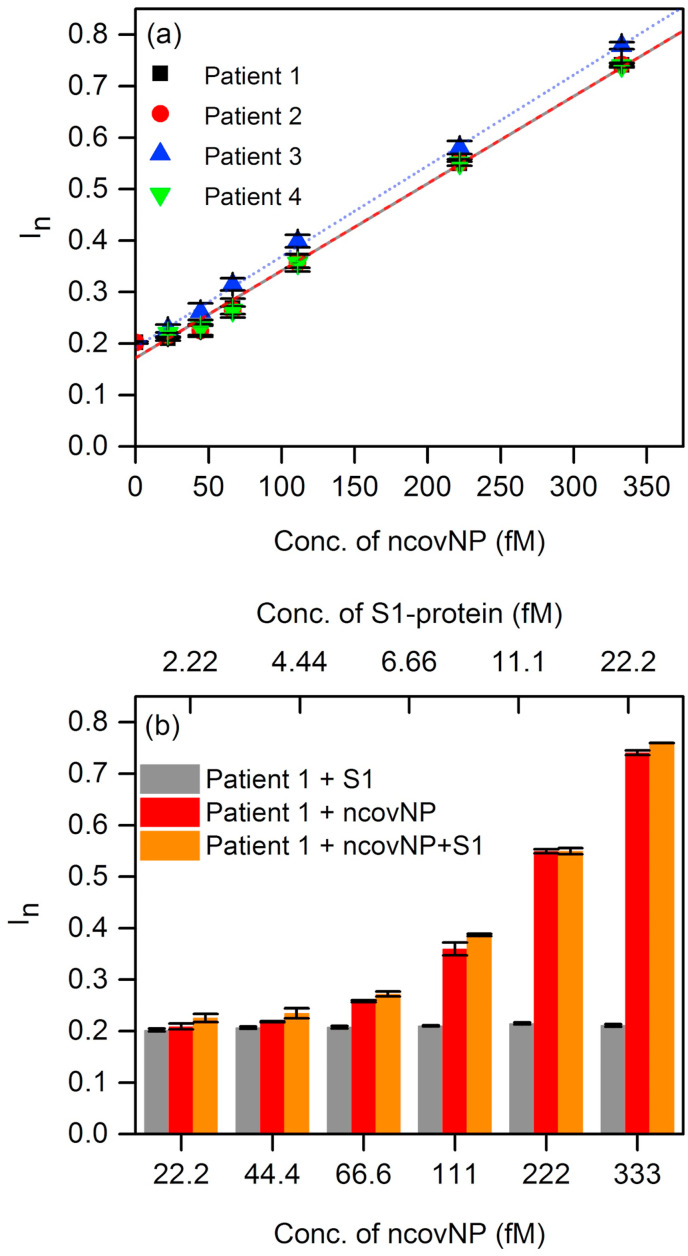

3.4. Sensor performance in clinical samples

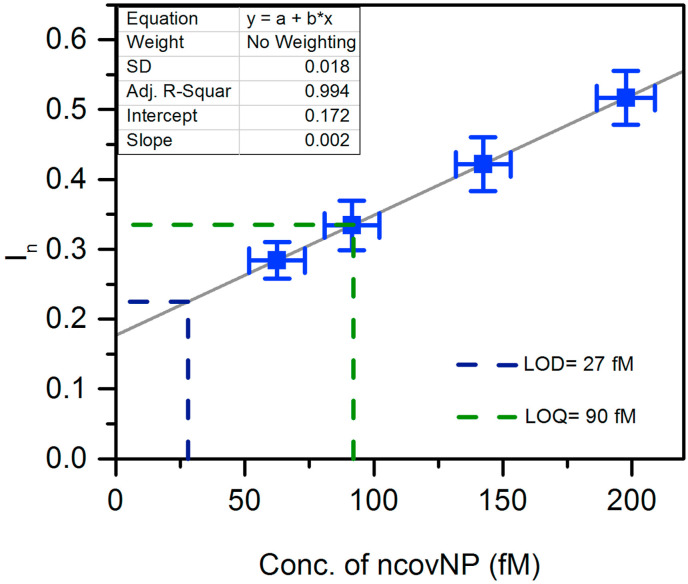

The clinical diagnostics feasibility of ncovNP sensor was assessed by analyzing the samples prepared from nasopharyngeal swab specimens of patients. First, the sensor was calibrated in COVID-19 negative samples spiked with known concentrations of ncovNP (Fig. 4 a). The sensor showed a pseudo-linear response versus ncovNP concentration in the range of 0.22–333 fM. LOD (27 fM) and LOQ (90 fM) were obtained by linearly regressing the averaged data of four COVID-19 negative patients. Thus, one can suppose that the patients' samples producing I n exceeding the values of 0.22 a.u. (corresponds to LOD) can be considered as COVID-19 positive. Moreover, the sensor demonstrated appreciable selectivity to ncovNP, since its response was almost insensitive to the addition of S1 in the COVID-19 negative sample, but raised immediately after ncovNP was spiked (Fig. 4b). These results promise that capability of the sensor to respond towards ncovNP will not be much disturbed in COVID-19 positive samples, where the other proteins of SARS-CoV-2 are presented.

Fig. 4.

(a) The calibration plots of ncovNP sensors obtained against COVID-19 negative samples in UTM, 20-fold diluted with LB and spiked with 22.2, 44.4, 66.6, 111, 222, 333 fM of ncovNP. (b) Cross-selectivity test of ncovNP sensor against S1, and mixture of ncovNP and S1 protein in COVID-19 negative sample in UTM 20-fold diluted with LB. The concentrations of ncovNP and S1 were selected in such a way to simulate their concentration ratio taking place in SARS-CoV-19 virus (Bar-On et al., 2020).

To explore the feasibility to use the sensors for COVID-19 diagnostics, they were tested against the RT-PCR confirmed COVID-19 samples. As it can be seen, four COVID-19 positive samples caused the responses, I n, higher than those against of the COVID-19 negative samples containing no ncovNP (y-intercept, 0.172 a.u.) or at least containing ncovNP at LOD (0.22 a.u.) (Table 1 , Fig. 5 ). It should be noted, samples of patient 6, patient 7 and patient 8, produced I n (0.331, 0.466 and 0.544 a.u.) corresponding to that caused by ncovNP at concentrations higher or close to LOQ (0.33 a.u.), while I n against the sample of patient 5 was higher than at LOD (0.22 a.u.). Despite the cycle threshold (Ct) values in RT-PCR analysis cannot be directly interpreted as viral load (Han et al., 2020), still a correlation between them and I n of the sensor was observed: the lower the Ct, the higher the I n. It is obvious that the sensor is responding to the presence of ncovNP in COVID-19 positive samples and demonstrated thus its potential in developing express tests for COVID-19.

Table 1.

Comparison of measurements made by ncovNP sensor and RT-PCR for COVID-19 positive nasopharynx swab specimens.

| SynLab sample code | ncovNP sensor response, In (a.u.) | Conc. of ncovNP as derived from Fig. 5, (fM)/(pg/ml) | RT-PCR, (Ct) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Patient 5 | 0.254 | 45 ± 11/2 ± 0.5 | 27 |

| Patient 6 | 0.331 | 90 ± 11/4 ± 0.5 | 27 |

| Patient 7 | 0.466 | 168 ± 11/8 ± 0.5 | 25 |

| Patient 8 | 0.544 | 214 ± 12/10 ± 0.5 | 22 |

Fig. 5.

The calibration plot (solid line) of ncovNP sensor obtained by linear regression of the averaged data in Fig. 4a. The blue rectangles represent data points corresponding In measured by ncovNP sensor against COVID-19 positive samples in UTM 20-fold diluted with LB. The error bars represent SDs (Miller and Miller, 2005). (For interpretation of the references to colour in this figure legend, the reader is referred to the Web version of this article.)

Finally, to examine the stability of the sensors, twelve (12) sensors were prepared and periodically, once a week, tested by the LB diluted COVID-19 negative samples spiked with ncovNP at concentration of 66.6 fM. The finding confirms that the response (I n) of the as-prepared sensors remained the same up to 9 weeks of storage, which reveals that ncovNP sensors have excellent long-term stability (Fig. S6).

4. Conclusion

In this work, we have developed for the first time a portable electrochemical sensor integrated with a molecular imprinted polymer (ncovNP-MIP) as a synthetic recognition element capable of selective detection of SARS-CoV-2 antigen (ncovNP). The synthesis parameters of ncovNP-MIP were optimized and the ability of the prepared sensor to selectively rebind the ncovNP was demonstrated. The sensor showed a linear response to ncovNP in the concentration range 2.22–111 fM in the lysis buffer, with LOD value of 15 fM and LOQ value of 50 fM. Moreover, it was able to differentiate ncovNP from interfering proteins (S1, BSA, CD48 and E2 HCV). The results of the sensor performance validation in the clinical samples of the nasopharynx swabs of patients were promising, confirming the capability of the sensor to detect ncovNP in the complex biological media.

The developed sensor that relies on a completely different approach as compared to the currently available SARS-CoV-2 antigen tests, could represent a valuable alternative as a portable diagnostic platform for the rapid screening for COVID-19.

Future work could be attempted to study the possible interference of the nucleoproteins of the other coronaviruses (MERS-CoV and SARS-CoV) to the ncovNP sensor response as well as to validate the sensor performance in patient's saliva samples, which enables non-invasive frequent sampling and reduces the need for trained healthcare professionals during collection.

CRediT authorship contribution statement

Abdul Raziq: Investigation, Validation, Writing - original draft, Visualization. Anna Kidakova: Conceptualization, Formal analysis, Visualization, Investigation. Roman Boroznjak: Investigation, Validation. Jekaterina Reut: Writing - original draft, Writing - review & editing. Andres Öpik: Funding acquisition. Vitali Syritski: Conceptualization, Methodology, Supervision, Writing - review & editing, Project administration, Funding acquisition, Resources.

Declaration of competing interest

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

Acknowledgement

This work was supported by Estonian Research Council grants PRG307 and COVSG34. The authors thank Icosagen AS and prof. Mart Ustav personally for kindly providing us with the SARS-CoV-2 nucleocapsid and spike proteins. The authors thank Synlab Eesti OÜ and Kaspar Ratnik and Paul Naaber personally for kindly providing the clinical samples and the laboratory facilities for their testing.

Footnotes

Supplementary data to this article can be found online at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bios.2021.113029.

Appendix A. Supplementary data

The following is the Supplementary data to this article:

References

- Bar-On Y.M., Flamholz A., Phillips R., Milo R. SARS-CoV-2 (COVID-19) by the numbers. eLife. 2020;9 doi: 10.7554/eLife.57309. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boroznjak R., Reut J., Tretjakov A., Lomaka A., Öpik A., Syritski V. A computational approach to study functional monomer‐protein molecular interactions to optimize protein molecular imprinting. J. Mol. Recogn. 2017;30:e2635. doi: 10.1002/jmr.2635. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Diao B., Wen K., Zhang J., Chen J., Han C., Chen Y., Wang S., Deng G., Zhou H., Wu Y. Accuracy of a nucleocapsid protein antigen rapid test in the diagnosis of SARS-CoV-2 infection. Clin. Microbiol. Infect. 2020 doi: 10.1016/j.cmi.2020.09.057. S1198743X2030611X In press ISSN - "1198-743X". [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Erdőssy J., Horváth V., Yarman A., Scheller F.W., Gyurcsányi R.E. Electrosynthesized molecularly imprinted polymers for protein recognition. TrAC Trends Anal. Chem. 2016;79:179–190. doi: 10.1016/j.trac.2015.12.018. Past , Present and Future challenges of Biosensors and Bioanalytical tools in Analytical Chemistry: a tribute to Prof Marco Mascini. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- EUA Authorized Serology Test Performance | [WWW Document], n.d. URL https://www.fda.gov/medical-devices/coronavirus-disease-2019-covid-19-emergency-use-authorizations-medical-devices/eua-authorized-serology-test-performance (accessed 1.5.21).

- In Vitro Diagnostics EUAs | FDA [WWW Document], 2020. URL https://www.fda.gov/medical-devices/coronavirus-disease-2019-covid-19-emergency-use-authorizations-medical-devices/vitro-diagnostics-euas#individual-antigen (accessed 12.14.20).

- FIND (Foundation for Innovative New Diagnostics). SARS-CoV-2 diagnostic pipeline. 2020 [WWW Document], n.d. URL https://www.finddx.org/covid-19/pipeline (accessed 10.28.20)..

- Han M.S., Byun J.-H., Cho Y., Rim J.H. RT-PCR for SARS-CoV-2: quantitative versus qualitative. Lancet Infect. Dis. 2020 doi: 10.1016/S1473-3099(20)30424-2. S1473309920304242 In press ISSN - "1473-3099". [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haupt K., Mosbach K. Molecularly imprinted polymers and their use in biomimetic sensors. Chem. Rev. 2000;100:2495–2504. doi: 10.1021/cr990099w. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jolly P., Tamboli V., Harniman R.L., Estrela P., Allender C.J., Bowen J.L. Aptamer–MIP hybrid receptor for highly sensitive electrochemical detection of prostate specific antigen. Biosens. Bioelectron. 2016;75:188–195. doi: 10.1016/j.bios.2015.08.043. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kidakova A., Reut J., Boroznjak R., Öpik A., Syritski V. Advanced sensing materials based on molecularly imprinted polymers towards developing point-of-care diagnostics devices. Proc. Est. Acad. Sci. 2019;68 doi: 10.3176/proc.2019.2.07. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kidakova A., Boroznjak R., Reut J., Öpik A., Saarma M., Syritski V. Molecularly imprinted polymer-based SAW sensor for label-free detection of cerebral dopamine neurotrophic factor protein. Sensor. Actuator. B Chem. 2020;308:127708. doi: 10.1016/j.snb.2020.127708. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Lai C.-C., Wang C.-Y., Ko W.-C., Hsueh P.-R. In vitro diagnostics of coronavirus disease 2019: technologies and application. J. Microbiol. Immunol. Infect. 2020 doi: 10.1016/j.jmii.2020.05.016. In press ISSN - "1684-1182". [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li T., Wang L., Wang H., Li X., Zhang S., Xu Y., Wei W. Serum SARS-COV-2 nucleocapsid protein: a sensitivity and specificity early diagnostic marker for SARS-COV-2 infection. Front. Cell. Infect. Microbiol. 2020;10:470. doi: 10.3389/fcimb.2020.00470. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu Ying, Liu Yueping, Diao B., Ren F., Wang Y., Ding J., Huang Q. 2020. Diagnostic Indexes of a Rapid IgG/IgM Combined Antibody Test for SARS-CoV-2. medRxiv. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lu C.-H., Zhang Y., Tang S.-F., Fang Z.-B., Yang H.-H., Chen X., Chen G.-N. Sensing HIV related protein using epitope imprinted hydrophilic polymer coated quartz crystal microbalance. Biosens. Bioelectron. 2012;31:439–444. doi: 10.1016/j.bios.2011.11.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miller James, Miller Jane. fifth ed. Pearson Education Limited; Harlow: 2005. Statistics and Chemometrics for Analytical Chemistry. [Google Scholar]

- Pan Y., Zhang D., Yang P., Poon L.L., Wang Q. Viral load of SARS-CoV-2 in clinical samples. Lancet Infect. Dis. 2020;20:411–412. doi: 10.1016/S1473-3099(20)30113-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Porte L., Legarraga P., Vollrath V., Aguilera X., Munita J.M., Araos R., Pizarro G., Vial P., Iruretagoyena M., Dittrich S. Evaluation of novel antigen-based rapid detection test for the diagnosis of SARS-CoV-2 in respiratory samples. Int. J. Infect. Dis. 2020;99:328–333. doi: 10.1016/j.ijid.2020.05.098. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ramanaviciene A., Ramanavicius A. Molecularly imprinted polypyrrole-based synthetic receptor for direct detection of bovine leukemia virus glycoproteins. Biosens. Bioelectron. 2004;20:1076–1082. doi: 10.1016/j.bios.2004.05.014. Special Issue on Synthetic Receptors. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rump A., Risti R., Kristal M.-L., Reut J., Syritski V., Lookene A., Ruutel Boudinot S. Dual ELISA using SARS-CoV-2 nucleocapsid protein produced in E. coli and CHO cells reveals epitope masking by N-glycosylation. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 2021;534:457–460. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2020.11.060. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scheller F.W., Zhang X., Yarman A., Wollenberger U., Gyurcsányi R.E. Molecularly imprinted polymer-based electrochemical sensors for biopolymers. Curr. Opin. Electrochem., Bioelectrochem. Electrocatal. 2019;14:53–59. doi: 10.1016/j.coelec.2018.12.005. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Seo G., Lee G., Kim M.J., Baek S.-H., Choi M., Ku K.B., Lee C.-S., Jun S., Park D., Kim H.G. Rapid detection of COVID-19 causative virus (SARS-CoV-2) in human nasopharyngeal swab specimens using field-effect transistor-based biosensor. ACS Nano. 2020;14:5135–5142. doi: 10.1021/acsnano.0c06726. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sharma P.S., Pietrzyk-Le A., D'Souza F., Kutner W. Electrochemically synthesized polymers in molecular imprinting for chemical sensing. Anal. Bioanal. Chem. 2012;402:3177–3204. doi: 10.1007/s00216-011-5696-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sharma P.S., Garcia-Cruz A., Cieplak M., Noworyta K.R., Kutner W. ‘Gate effect’ in molecularly imprinted polymers: the current state of understanding. Curr. Opin. Electrochem. 2019;16:50–56. doi: 10.1016/j.coelec.2019.04.020. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Shumyantseva V.V., Bulko T.V., Sigolaeva L.V., Kuzikov A.V., Archakov A.I. Electrosynthesis and binding properties of molecularly imprinted poly-o-phenylenediamine for selective recognition and direct electrochemical detection of myoglobin. Biosens. Bioelectron. 2016;86:330–336. doi: 10.1016/j.bios.2016.05.101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Silva B.V., Rodríguez B.A., Sales G.F., Maria Del Pilar T.S., Dutra R.F. An ultrasensitive human cardiac troponin T graphene screen-printed electrode based on electropolymerized-molecularly imprinted conducting polymer. Biosens. Bioelectron. 2016;77:978–985. doi: 10.1016/j.bios.2015.10.068. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tai D.-F., Lin C.-Y., Wu T.-Z., Chen L.-K. Recognition of dengue virus protein using epitope-mediated molecularly imprinted film. Anal. Chem. 2005;77:5140–5143. doi: 10.1021/ac0504060. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tretjakov A., Syritski V., Reut J., Boroznjak R., Volobujeva O., Öpik A. Surface molecularly imprinted polydopamine films for recognition of immunoglobulin G. Microchim. Acta. 2013;180:1433–1442. doi: 10.1007/s00604-013-1039-y. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Tretjakov A., Syritski V., Reut J., Boroznjak R., Öpik A. Molecularly imprinted polymer film interfaced with Surface Acoustic Wave technology as a sensing platform for label-free protein detection. Anal. Chim. Acta. 2016;902:182–188. doi: 10.1016/j.aca.2015.11.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Viswanathan S., Rani C., Ribeiro S., Delerue-Matos C. Molecular imprinted nanoelectrodes for ultra sensitive detection of ovarian cancer marker. Biosens. Bioelectron. 2012;33:179–183. doi: 10.1016/j.bios.2011.12.049. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang Y., Zhang Z., Jain V., Yi J., Mueller S., Sokolov J., Liu Z., Levon K., Rigas B., Rafailovich M.H. Potentiometric sensors based on surface molecular imprinting: detection of cancer biomarkers and viruses. Sensor. Actuator. B Chem. 2010;146:381–387. doi: 10.1016/j.snb.2010.02.032. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- World Health Organization . World Health Organization; 2020. Coronavirus Disease 2019 (COVID-19): Situation Report, 52 (No. 52) [Google Scholar]

- Zhao W., Li B., Xu S., Huang X., Luo J., Zhu Y., Liu X. Electrochemical protein recognition based on macromolecular self-assembly of molecularly imprinted polymer: a new strategy to mimic antibody for label-free biosensing. J. Mater. Chem. B. 2019;7:2311–2319. doi: 10.1039/C9TB00220K. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhou P., Yang X.-L., Wang X.-G., Hu B., Zhang L., Zhang W., Si H.-R., Zhu Y., Li B., Huang C.-L. A pneumonia outbreak associated with a new coronavirus of probable bat origin. Nature. 2020;579:270–273. doi: 10.1038/s41586-020-2012-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.