Abstract

Research that analyzes the effect of different environmental factors on the impact of COVID-19 focus primarily on meteorological variables such as humidity and temperature or on air pollution variables. However, noise pollution is also a relevant environmental factor that contributes to the worsening of chronic cardiovascular diseases and even diabetes. This study analyzes the role of short-term noise pollution levels on the incidence and severity of cases of COVID-19 in Madrid from February 1 to May 31, 2020. The following variables were used in the study: daily noise levels averaged over 14 days; daily incidence rates, average cumulative incidence over 14 days; hospital admissions, Intensive Care Unit (ICU) admissions and mortality due to COVID-19. We controlled for the effect of the pollutants PM10 and NO2 as well as for variables related to seasonality and autoregressive nature. GLM models with Poisson regressions were carried out using significant variable selection (p < 0.05) to calculate attributable RR. The results of the modeling using a single variable show that the levels of noise (leq24 h) were related to the incidence rate, the rate of hospital admissions, the ICU admissions and the rate of average cumulative incidence over 14 days. These associations presented lags, and the first association was with incidence (lag 7 and lag 10), then with hospital admissions (lag 17) and finally ICU admissions (lag 22). There was no association with deaths due to COVID-19. In the results of the models that included PM10, NO2, Leq24 h and the control variables simultaneously, we observed that only Leq24 h went on to become a part of the models using COVID-19 variables, including the 14-day average cumulative incidence. These results show that noise pollution is an important environmental variable that is relevant in relation to the incidence and severity of COVID-19 in the Province of Madrid.

Keywords: COVID-19, Morbidity, Mortality, Traffic noise, Air pollution

1. Introduction

In analyzing the impact of different environmental factors on the incidence and severity of COVID-19, studies focus primarily on the role of meteorological variables or air pollution variables. In terms of meteorological variables, the majority of studies consider temperature and humidity (Holtmann et al., 2020; CDC, 2020; Lipsitch& Phil, 2020; Tobías et al., 2020; Sajadi et al., 2020). Other studies also consider parameters such as ultraviolet radiation (Yao et al., 2020) and wind speed (Islam et al., 2020) as atmospheric variables that can affect the spread of SARS-CoV-2. Other research focuses on geographic factors such as latitude, which indirectly represents conditions of temperature and humidity, which could explain the behavior of the spread of the virus (CEBM, 2020).

On the other hand, the existence of a clear mechanism through which air pollution can affect the immunological system as well as the worsening of respiratory, cardiovascular and endocrine illnesses (Sood et al., 2018; Domingo Rovira, 2020), upon which COVID-19 also acts (Hu et al., 2020; Arentz et al., 2020) is still unclear. Thus, multiple studies have been recently carried out that focus on the effect of particulate matter, specifically on concentrations of NO2 (Comunian et al., 2020; Zoran et al., 2020; Zhao et al., 2020; Ogen et al., 2020; Setti et al., 2020; Bontempi E., 2020). Some studies even analyze the joint effect of meteorological variables and air pollution variables (Linares et al., 2021).

The definition of air pollution includes “the presence of substances or energy forms in the air …” (BOE, 2007), and a clear biological mechanism exists by which noise affects the immune system (Recio et al., 2016). Exposure to noise also worsens—over the short-term—the same pathologies as air pollution (Recio et al., 2017; WHO et al., 2018) and sometimes has an even greater impact than does air pollution (Tobías et al., 2015). Despite this, there is practically no study that analyzes the impact of exposure to noise on the incidence and severity of COVID-19. The studies that have been carried out related to the possible relationship between noise and COVID-19 concern the decrease in hospital admissions due to cardiovascular causes resulting from the registered decrease in the levels of noise during the confinement (Dutheil et al., 2020).

On January 31, 2020, the first case of COVID-19 was registered in Spain, and by May 31 there were 239,429 registered cases and 27,127 deaths. At that time, Spain was European country with the third highest numbers in terms of confirmed cases, after Russia and the UK (MSCBS, 2020a). More than 28.7 percent of cases occurred in the region of Madrid, and Madrid accounted for around 32 percent of the total number of fatalities registered in Spain. Madrid was the region in Spain with the greatest number of cases and deaths (MSCBS, 2020a).

On the other hand, nine million people in Spain endure noise levels above the 65 dB recommended by the World Health Organization (WHO). In fact, 72.3 percent of Spaniards believe that they live in a noisy city. In Madrid, 92.9 percent feel this way, and Madrid is the city with the highest percentage, followed by Barcelona and Seville (DKV-GAES, 2015).

The objective of this study was to analyze the possible daily relationship that exists over the short-term between noise levels registered and 14-day averages in Madrid and rates of incidence, 14-day average cumulative incidence, hospital admissions, Intensive Care Unit (ICU) admissions and deaths due to COVID-19 during the period of February 1 to May 31, 2020. We controlled for the effect of the pollutants PM10 and NO2 and for different confounding variables.

2. Materials and methods

2.1. Dependent and independent variables

The COVID-19 positive case data were based on a positive result of the PCR test, for 99.74 percent of the data. The rest were diagnosed based on symptoms compatible with the disease.

Cases defined in this way refer to daily cases in the Province of Madrid that occurred during the period of February 1 to May 31, 2020. During this period a state of alarm was declared, and the population was confined homebound except for essential travel, beginning on March 14, with restrictions on movements and social interactions (BOE, 2020). The state of alarm remained in place until June 21, 2020 (BOE, 2020b).

The data analyzed correspond to the number of cases diagnosed as COVID-19 positive in different categories: number of cases, number of emergency room admissions, number of Intensive Care Unit (ICU) admissions, and the number of deaths due to COVID-19. Data were provided by the National Center for Epidemiology at the Carlos III Health Institute. The population data for the Province of Madrid were provided by the National Statistics Institute (NSI). Based on these data, we calculated the following rates:

COVID-19 incidence rate per 100,000 inhabitants: (Number of COVID-19 positive cases/population) X 100,000 inhabitants.

Rate of emergency room admissions for COVID-19 per 100,000 inhabitants: (Number of COVID-19 positive emergency room admissions/population) X 100,000 inhabitants.

In the case of ICU admissions and deaths, rates per million inhabitants were used, to result in a lower number.

Rate of ICU hospital admissions for COVID-19 per 1,000,000 inhabitants: (Number of COVID-19 positive ICU admissions/population) X 1,000,000 inhabitants.

Rate of deaths due to COVID-19 per 1,000,000 inhabitants: (Number of COVID-19 positive deaths/population) X 1,000,000 inhabitants.

Average cumulative incidence over 14 days: Average value of positive COVID-19 cases over a period of 14 days.

The independent variables were made up of noise levels and data on air pollution.

Noise level data refer to 24-h average values (Leq24 h) in A-weighted dB—dB(A) (Leq24 h) —obtained based on information from the sources (IOS, 2017):

-

-

The noise monitoring network of the City Council of Madrid, made up of 30 operating stations (Ayuntamiento de Madrid, 2020).

-

-

The noise monitoring network of the Spanish Airport Navigation Area (AENA), made up of a total of 22 stations distributed in different municipalities of the Province of Madrid, in the area covered by the Madrid Barajas airport (AENA, 2020).

Each element in the data series consists of the arithmetic average of the indicators obtained for the 52 monitoring stations, which characterize the total noise, without separation of the sources of sound. The air pollution data are made up of the average daily values of concentrations of de PM10 and NO2 in μg/m3, obtained as an average of the values measured at the stations located in the Community of Madrid. These data were provided by the Spanish Environmental Ministry (MITECO). The average daily values were used to calculate the 14-day average values for these independent variables.

As control variables, meteorological data have been used: Daily maximum temperature and absolute humidity. These values made up the average values of the observations corresponding to the AEMET stations located in Madrid. They were provided by the State Meteorological Agency (AEMET).

2.2. Analysis methodology

Generalized Linear Regression Models (GLM) with Poisson link were developed based on the dependent variables (average rates and incidence of positive COVID-19 cases) and the independent variables (noise and air pollution). These models controlled for the series trend and seasonality of 120, 90, 60 and 30 days as well as the autoregressive nature of the series. We also controlled for weekly seasonality by including the days of the week as dummy variables in the models. For example, when the data correspond to Tuesday, the value in the data cell corresponding to the variable “day of the week” is equal to 1; all the other days of the week for the same data are zero.

First GLM were carried out between each dependent variable and the average daily values of the independent variables and later with the 14-day average values of the independent variables. The modeling process using a single variable served to establish the time lags in which statistically significant associations were produced between the dependent variables, referred to as lags, and the independent variables.

The lags considered were those of up to 28 days, given that the average time between infection and death tends to be around 18 days (Verity et al., 2020), although there are other studies that stretch it to up to 2 months (Chu et al., 2004) Later, multivariate models were carried out that included the noise variable (Leq 24 h) and the air pollution variable (PM10 and NO2) and took into account the aforementioned control variables.

A weekly distributed lag model was used. In a first step, the lags were introduced for the independent variables from 0 to 7 days. In a second step, the lags corresponding to 8–14 days were introduced, while maintaining the lag variables that were statically significant in the first step, and so on up to 28 days to complete the range of lag days considered in the analysis.

Based on the values of the estimators, relative risks were calculated (RR) in the form RR = eβ with β being the value of the estimator obtained in the Poisson modeling.

A negative coefficient in the estimator indicates that an increase in the value of the independent variable is associated with a decrease in the value of the dependent variable. The RR is calculated by an increase of 10 μg/m3 of PM10 and NO2 and 1 dB(A) in the Leq24 h value.

The variable selection method used was back-stepwise and associations with p < 0.05 were considered to be statistically significant. We controlled for over- and under-dispersion.

3. Results

69,987 cases of COVID were registered during the period analyzed, with a maximum daily value of 2834 cases and a minimum of two. Of these cases, 33,570 (47.96%) were admitted to the hospital (2.93%) were admitted to the ICU and 8306 people (11.87%) died.

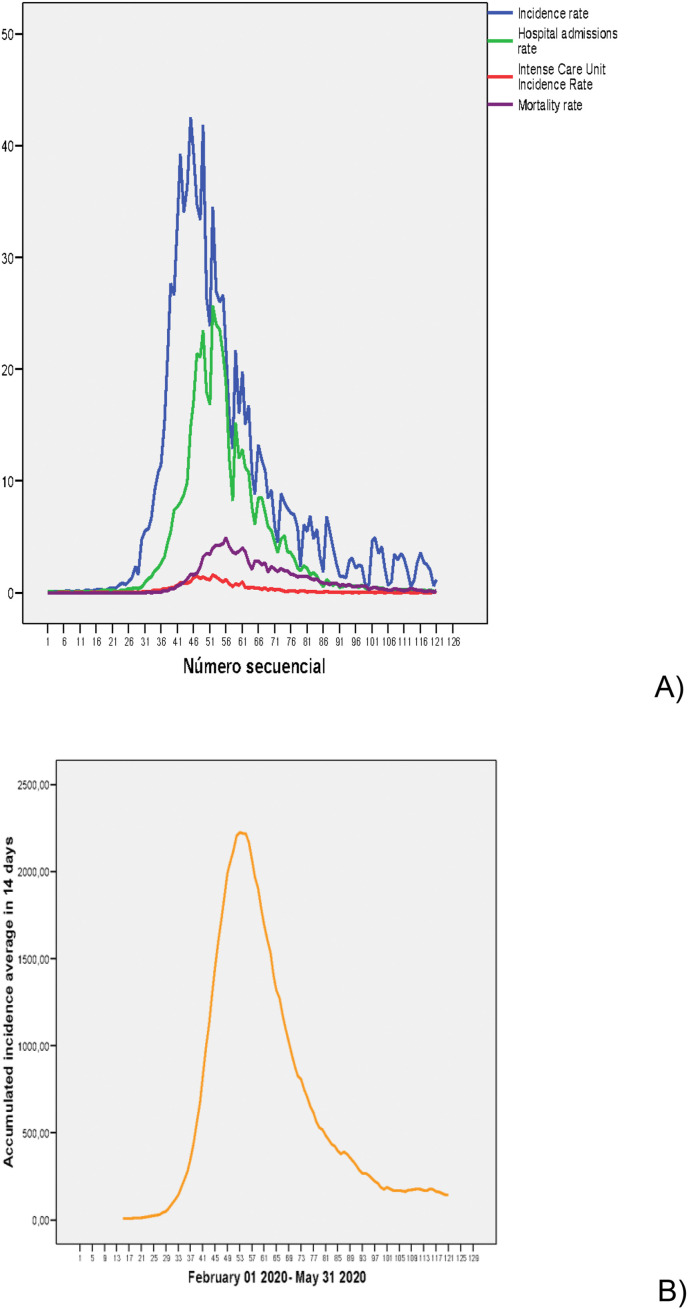

Table 1 shows the descriptive statistics for the incidence rates, rates of hospital admission and ICU admission, death rate and the average incidence over 14 days. Fig. 1 A and B shows the time evolution during the period analyzed, which corresponds to the so called “first wave,” as can be observed.

Table 1.

Descriptive statistics of the COVID-19 rate variables and independent variables analyzed during the period 02-01-2020 to 05-31–2020.

| Maximum | Minimum | Mean | Std. Deviation | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Incidence rate a | 42.53 | 0.03 | 8.68 | 11.12 |

| Hospital admissions rate a | 25.71 | 0.03 | 4.16 | 6.45 |

| Intensive Care Unit (ICU) admissions rateb | 15.76 | 0.00 | 2.54 | 3.98 |

| Mortality rateb | 49.22 | 0.00 | 10.30 | 12.91 |

| Cumulative average incidence over 14 days | 2225.0 | 7.3 | 645.0 | 684.2 |

| Leq24 h (dB(A)) | 61.3 | 51.1 | 55.7 | 2.4 |

| PM10 (μg/m3) | 85.1 | 5.1 | 15.8 | 12.2 |

| NO2 (μg/m3) | 57.3 | 2.5 | 18.8 | 13.6 |

Cases per 100,000 inhabitants.

Cases per million inhabitants.

Fig. 1.

A) Temporal evolution of incidence rate; hospital admissions rate; intensive care unit admission rate, and mortality rate from February 1, 2020 to May 31, 2020. All in cases per 100,000 inhabitants. B) Temporal evolution of average cumulative incidence over 14 days.

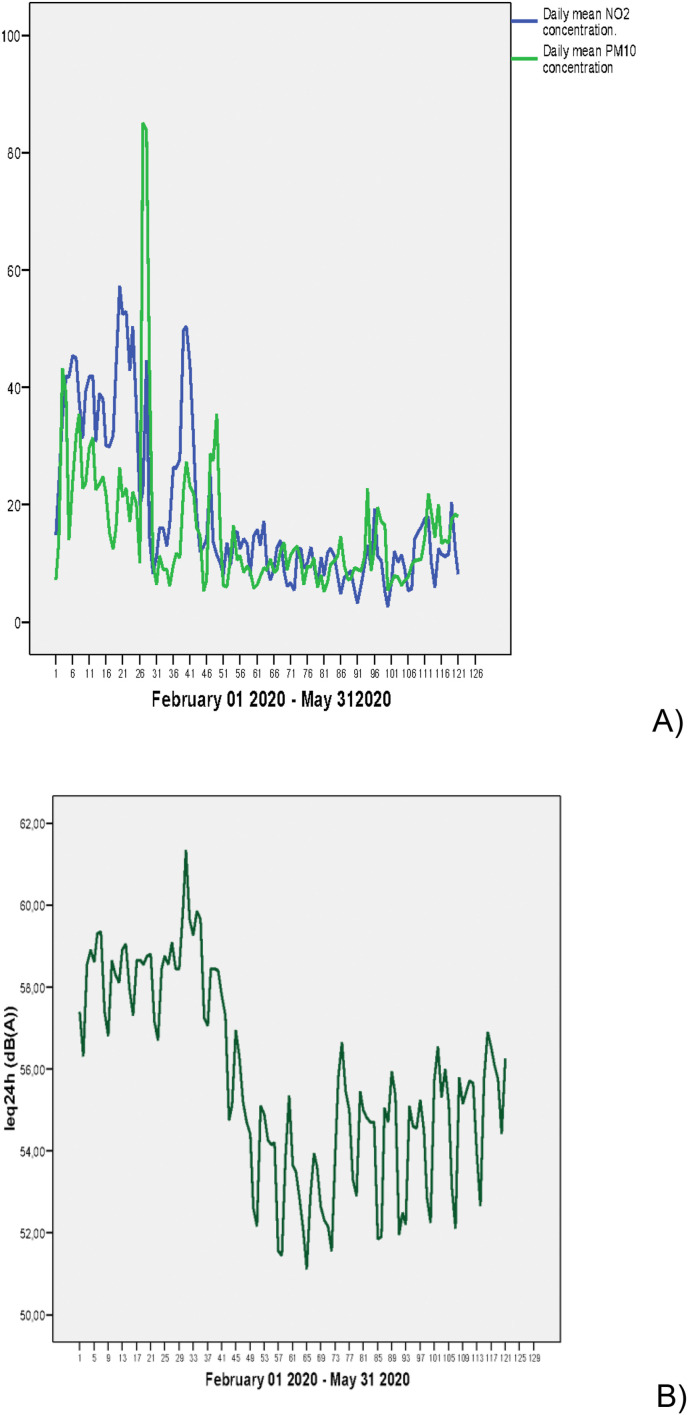

The descriptive statistics of the independent variables also appear in Table 1. Fig. 2 A and B shows the time evolution for both PM10 and NO2 and for Leq24 h, which shows an abrupt decrease in these values. It is especially marked in the case of Leq24 h, where the range of variation in the values of Leq24 h is of 10.2 dB(A), compared to 80 μg/m3 for PM10 and 54.8 μg/m3 for NO2.

Fig. 2.

Temporal evolution of: A) Daily mean concentration of NO2 and PM10 (μg/m3); B) Leq24 h (dB(A)).

Table 2 shows the Pearson bivariate correlation coefficients between the independent variables, with statistically significant associations between all of the variables considered. It should be noted that there is a high correlation (0.672) between the values of NO2 and Leq24 h, whereas the correlation between PM10 and Leq24 h is slightly lower (0.391).

Table 2.

Pearson correlation coefficients. ** significance p < 0.01

| NO2 | PM10 | Leq24 h | |

|---|---|---|---|

| NO2 | 1 | 0.519** | 0.672** |

| PM10 | 0.519** | 1 | 0.391** |

| Leq24 h | 0.672** | 0.391** | 1 |

Table 3 shows the results of the single variable modeling in relation to the average daily values. The noise measured via Leq24 h is related both to the incidence rate as well as the hospital admission rate, ICU admissions and the cumulative incidence rate over 14 days. These associations show time lags, the first of which is associated with incidence (lag 7 and 10), and later hospital admissions (lag 17), and finally ICU admissions (lag 22). There was no association with deaths due to COVID-19. Table 3 also shows the single variable models for PM10 and NO2.

Table 3.

Lags in which statistically significant associations are established between the daily values of the independent variables and the analyzed COVID-19 variables.

| Leq24 h (dB(A)) | PM10 (μg/m3) | NO2 (μg/m3) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Incidence rate | Single Variable | 7/10 | 12 | 0/14/21 |

| All Variables | 7/10 | Without effect | Without effect | |

| Cumulative average incidence over 14 days | Single Variable | 17 | 25/28 | Without effect |

| All Variables | 17 | 25/28 | Without effect | |

| Hospital admissions rate | Single Variable | 17 | 20 | 5/19 |

| All Variables | 24 | Without effect | 5 | |

| Intensive Care Unit admissions rate | Single Variable | 22 | 14/19 | 21/28 |

| All Variables | 22 | Without effect | 28 | |

Table 4 shows the lags in which associations are produced for the 14-day average variables, and they show very similar behavior to what was obtained for the daily values.

Table 4.

Lags in which statistically significant associations are established between the values averaged over 14 days of the independent variables and the analyzed COVID-19 variables.

| Leq24 h (dB(A)) | PM10 (μg/m3) | NO2 (μg/m3) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Incidence rate | Single Variable | 7 | 11 | 13 |

| All Variables | 7 | 11 | 13 | |

| Cumulative average incidence over 14 days | Single Variable | 11 | 15 | Without effect |

| All Variables | 11 | 15 | Without effect | |

| Hospital admissions rate | Single Variable | 12 | 14 | 28 |

| All Variables | 12 | 14 | Without effect | |

| Intensive Care Unit admissions rate | Single Variable | 12 | 20 | 21/28 |

| All Variables | 22 | Without effect | 21 | |

Table 5 shows the models with all of the variables, which simultaneously include PM10, NO2 and Leq24 h and the control variables for both the daily values as well as the 24-h average values. As shown in the table, Leq24 h is the variable that would become a part of all of the models used with the COVID-19 variables, including cumulative average incidence over 14 days.

Table 5.

Relative risks corresponding to final models with all the independent variables. The RR correspond to an increase of 1 dB(A) in Leq24 h values and 10 μg/m3 of PM10 and NO2 concentrations.

| DAILY VALUES | AVERAGED VALUES (0–14 DAYS) | |

|---|---|---|

| Incidence rate | Leq24 (7) RR: 1.24 (1.18 1.30) Leq24 (10) RR: 1.07 (1.03 1.13) |

Leq24 (7) RR: 1.29 (1.11 1.50) PM10 (11) RR: 1.33 (1.03 1.73) NO2 (13) RR: 1,45 (1,14 1,76) |

| Cumulative average incidence over 14 days | Leq24 (17) RR: 1.01 (1.00 1.02) PM10 (25) RR: 1.01 (1.00 1.01) PM10 (28) RR: 1.01 (1.00 1.01) |

Leq24 (11) RR: 1.28 (1.20 1.36) PM10 (15) RR: 1.09 (1.06 1.12) |

| Hospital admissions rate | Leq24 (17) RR: 1.07 (1.00 1.02) NO2 (5) RR: 1.12 (1.01 1.24) |

Leq24 (12) RR: 1.22 (1.01 1.48) PM10 (14) RR: 1.56 (1.06 2.20) |

| Intensive Care Unit admissions rate | Leq24 (22) RR: 1.13 (1.04 1.22) NO2 (28) RR: 1.12 (1.02 1.22) |

Leq24 (12) RR: 1.73 (1.38 2.19) NO2 (21) RR: 1.43 (1.08 1.89) |

In terms of the meteorological variables used as control variables, the GLM models show that the coefficients related to COVID-19 variables are negative.

4. Discussion

One fact worth highlighting related to the COVID-19 variables is the high proportion of admissions for the cases detected, which was over 47 percent. Also notable is the high percentage of deaths, which was around 12 percent, much higher than the 4 percent that was established by the WHO as the worldwide death rate with respect to those diagnosed (WHO, 2020). The cause of these high percentages is probably the fact that during the period in question, Madrid only provided PCR testing to those people who presented symptomatology of a certain level of severity. This was shown in a study of the prevalence of SARS-CoV-2 in Spain (ENE-COVID) (Pollán et al., 2020) that stated that, “one in three infections seems to be asymptomatic, while a substantial number of symptomatic cases remained untested”. It is currently estimated that in this period only 10 percent of true cases were detected. On the other hand, the severity of the cases detected could also explain the effects in short-term lags for the case of NO2 in terms of incidence, hospital admissions and ICU admissions (Linares et al., 2021).

Fig. 2A and B clearly show a decrease in the concentrations of the pollutants and noise levels in Madrid during the period analyzed. If the values of the first and last week of the study period are compared, there was a decrease in the concentrations of 34.5 percent for PM10 and 66.8 percent for NO2 (Linares et al., 2021). In the case of Leq24 h, the decrease between the first and final weeks was 3 dB(A), and the decrease reached 5.4 dB(A) for some periods during the strictest parts of the confinement. These results agree with the decreases observed in the city of Madrid in other studies that estimated a decrease of between 4 and 7 dB(A) for different zones in the city (Asensio et al., 2020).

In terms of the meteorological variables, the GLM models show that the coefficients related to COVID-19 variables are negative. That is to say, low and humid temperatures are related to higher incidence rates. On the other hand, the serological study of the prevalence of SARS-CoV-2 in Spain (ENE-COVID) (Pollán et al., 2020) indicates that a lower prevalence of COVID-19 in Spain was produced in coastal regions that, during the time of the study and in general, are characterized by higher temperatures and humidity than the interior areas of the peninsula (AEMET, 2020).

The decrease in automobile traffic was the primary cause of the decreases that occurred in both air pollutants and noise pollution. Automobile traffic is the primary cause of noise in large cities (Navares et al., 2020). This common source explains the collinearity found between NO2 and Leq24 h shown in Table 2. In the case of PM10 this collinearity decreased in a clear way, although it maintained statistical significance due to the fact that, during the period, both PM10 and automobile traffic were amplified by the intrusion of natural-origin Saharan dust at the end of February of 2020 (MITECO et al., 2020). This can be observed in the registered increase of more than 80 μg/m3 in Fig. 2a.

However, the most noteworthy result of this study is the robust association found between noise levels and the COVID-19 variables analyzed, with the exception of mortality.

Table 3 shows the lags for which there was an association established between daily values and the COVID-19 variables analyzed. First, the incidence rate for lags 7 and 10 is coherent with the time necessary for the incubation period of the disease and the onset of symptoms, established between 2 and 12 days after contracting the disease (Lauer, 2020), and the days that pass prior to the worsening of symptoms and consequent hospital admission (MSCBS, 2020b). In our case, hospital admissions were produced in lag 17, which would account for those people who, once infected, experienced worsening of their symptoms and had to go to the hospital, and finally, for those people for whom symptoms became so severe that they had to be admitted to the ICU.

There are three possible mechanisms that could explain these associations between noise levels and the incidence and severity of COVID-19 measured through hospital admissions and ICU admissions.

On one hand, noise is capable of influencing the immune system through three factors, one of which is the stressful nature of noise (Recio et al., 2016). The association between noise and psychological stress and the occurrence and worsening of respiratory diseases has been thoroughly studied (Aich et al., 2009). The hypothalamus activates the adrenal medullary and the sympathetic arm of the autonomic nervous system, starting SAM regulation with an increase in blood flow to the muscles, an increase in blood pressure and in heart rate and respiratory rate, along with a decrease in gastro-intestinal activity. The hypothalamus then activates the adrenal cortex, which releases cortisol and other glucocorticoids. Among other activities, glucocorticoids are responsible for ensuring the flow of blood glucose to the brain and for elevating or stabilizing blood glucose levels, for mobilizing protein reserves, or regulating the immune system (Irwin 2012).

Second, sleep alterations are produced by nighttime noise. Studies carried out in animals and humans have found associations between sleep wave cycles and the neuroendocrine and immune systems (Majde and Krueger, 2005). Sleep inhibits several structures of the central nervous system, so the activity of the cortical connections is greatly reduced to seek the isolation of the outside world. Both during and out of sleep the limbic system is on permanent alert, configuring the primary emotions that the hippocampus contributes to modeling through memory. During sleep these unconscious emotions can cause autonomic awakenings and activate the hypothalamus, disturbing the REM phase by background noise, or the phases of deep sleep or slow waves (SWS) by noise peaks (Pirrera et al., 2010).

Third, there is the impact of oxidative stress. Inflammatory processes associated with psychological stress as a result of traffic noise are one source of oxidative stress. Oxidative stress has the effect of a reduction in antioxidants during the immune response and the promotion of infectious diseases (Trefler et al., 2014). In addition to debilitating the immune system, there are numerous studies that link short and long-term noise to morbidity and mortality related to respiratory and cardiovascular illnesses and diabetes. The WHO guide (WHO, 2018) highlights the quality of evidence between exposure to traffic noise and incidence of diabetes is moderate, based on a cohort study (Van Kempen et al., 2018). New cohort studies in Switzerland (Eze et al., 2017) and in Barcelona, Spain, shows that long-term exposure to noise is related to increased diabetes mortality (Barceló et al., 2016). The WHO guides (WHO, 2018) highlight the quality of evidence between exposure to traffic noise and incidence of diabetes is moderate, based on a cohort study (van Kempen et al., 2018). New cohort studies in Switzerland (Eze et al., 2017) and in Barcelona, Spain, shows that long-term exposure to noise is related to increased diabetes mortality (Barceló et al., 2016). Short-term exposure to traffic air pollution has been related to nighttime noise in Madrid, Spain (Tobías et al., 2015b).

These are diseases that are associated with poor prognosis in patients who have been diagnosed with COVID-19 (Hu et al., 2020; Arentz et al., 2020; Zhou et al., 2020). Short-term noise is related to hospital emergency admissions due to both cardiovascular and respiratory diseases (Tobías et al., 2001). However, it is also related to short-term mortality due to circulatory, respiratory and metabolic issues (Recio et al., 2017; WHO et al., 2018; Linares and Díaz, 2019), especially for those over age 65 (Recio et al., 2017), which is the population for which COVID-19 has had the greatest incidence in many countries in Europe (Remuzzi et al., 2020) and in Spain (RENAVE, 2020). These are the same mechanisms that underlie the associations found with air pollution (Linares et al., 2021; Domigo and Rovira, 2020; Frontera et al., 2020; Zoran et al., 2020).

Furthermore, there is another factor that can explain a role of noise beyond the associations based solely on the biological mechanisms already mentioned, which is that noise is an indicator of human activity, especially in large cities (Linares and Díaz, 2007). Noise is a reflection of the number of automobiles that circulate in the city (Navares et al., 2020), and it also accounts for the presence of people in the streets and activity in leisure areas (Asensio et al., 2020). Therefore, noise can explain factors related to vehicle mobility and human activity that is related to the transmission of COVID-19. Furthermore, this type of pollution is less dependent on meteorological conditions than air pollution.

In other words, noise is an indirect indicator of an increase in human activity, which could indicate a greater risk COVID-19 transmission, a greater increase in the incidence of cases and a greater number of severe cases among vulnerable groups.

This added effect of noise pollution that is similar to the short-term effect of NO2 or PM10 could explain why noise shows associations with all of the COVID variables considered (with the exception of mortality), which is something that does not occur in the case of the air pollutants, as shown in Table 3.

The results in Table 4 that refer to the 14-day average values serve to justify the findings related to the daily values, and to support their robustness. The fact that the associations found for the daily values are also found for the averaged values indicate that they are not due to seasonal factors that are similar between the dependent and independent variables.

4.1. Strengths and weaknesses of this study

One of the principal strengths of this study is the length of the series. Even though the series length is 121 days, or four months, it is greater than the majority of the studies carried out to date. On the other hand, the period analyzed corresponds to a period that includes a time both pre-state of alarm and during the state of alarm, with homogeneous restrictions applying to the entirety of the zone of the study. The entire area considered in the study was subjected to the same conditions in terms of “physical distancing and other public health interventions” (Villeneuve and Goldberg 2020).

The duration of the series allowed for carrying out generalized linear models with control variables such as trend, seasonalities and autoregressive components. Furthermore, it allowed for carrying out multivariate models that included both pollution variables and noise while accounting for the collinearity among them.

On the other hand, the Province of Madrid has 6,685,471 inhabitants, 49 percent of whom live in the city of Madrid, which has an air pollution and noise measurement network made up of 30 measurement stations. In the rest of the area, there are 22 fixed stations that measure noise. In other words, there are 52 stations for a territory of 8000 Km2. As such, the spatial allocation is important (one station for every 1.7 km) and provides a high level of representativeness to the measures of the independent variables (Villeneuve and Goldberg 2020).

In addition, for much of the analysis period, the population was confined to their homes. Mobility was greatly reduced, so the exposure of people was not as variable as it would be during a period of normality.

Another of the study strengths is the robustness of the results, first among the lags for which associations were established, which are coherent with the biological mechanisms that link the different variables analyzed and the incidence and severity of the disease to the incubation period and the course of the disease. In addition, associations were not established only with a single indicator, but rather among four indicators, with coherent results among them. This robustness also applies to the multivariate models and to the results obtained for both the daily series and the averaged series.

This study used an ecological time series design, which includes all the epidemiological limitations inherent in this type of study, especially the ecological fallacy, which is a weakness of the study, since it is impossible to know which of the three possible hypotheses that associate noise with the COVID-19 variables is the one that truly explains the association. The fact that authors have performed the analysis for the Madrid geographical area as single area, means they cannot compare among different zones with diverse characteristics, as demographic or socioeconomics variables, as it is conducted in other studies (Saez at al. 2020; Ahmadi et al., 2020; Coccia et al., 2020; Pequeno et al., 2020).

In the analysis all the variables were averaged, weighted by population. However, not all inhabitants in the small area or bigger area actually had these mean values of the variables, leading to a measurement error, most likely random. If the explanatory variables are measured with error, the estimators will be inconsistent (Greene, 2018). Nevertheless, if the between-area variability of the variable measured with error is much greater than the within-area variability of such variable then the effect of measurement error on the estimator consistency may be negligible (Elliott and Savitz, 2008). In our case, the Madrid region is an administrative unit that, in most cases, is quite heterogeneous. In any case, when, as in the region, this criterion is not met, the presence of measurement errors tends to underestimate the effect of the variable measured with error (Saez et al., 2020).

On the other hand, paradoxically, the length of the series could be considered a weakness, because it only accounts for a period of four months, without taking into account complete annual variation. Furthermore, the time period is totally anomalous in terms of the decrease in the pollutants and in noise as well as human confinement, therefore the exposure to the external environmental variables represents an important bias. On the other hand, the conditions under which the data were obtained corresponds to a time in which the case definition was only registered when people already presented important symptoms of the disease.

The two points mentioned imply the need for prudence in extrapolating the results of the study to points in time other than those in which the study was carried out. Future studies will analyze, together and with more depth, the impact of climate variability, air pollution and other extrinsic factors in COVID-19 transmission. They should also be able to consider other important factors that were not considered here, such as the connectivity between places with high incidence, patterns of social relationships, the susceptibility of the population, and surveillance data on respiratory infections, for example.

5. Conclusions

The results obtained in this study show that the noise measured through the Leq24 indicator are related to the incidence and severity of COVID-19 in the Province of Madrid. This effect is independent of that found for air pollution and predominant in relation to the effect of NO2 and PM10.

Disclaimer

The researchers declare that they have no conflict of interest that would compromise the independence of this research. The views expressed by the authors do not necessarily coincide with those of the institutions they are affiliated with.

Credit author statement

Julio Díaz. Original idea of the study. Study design; Elaboration and revision of the manuscript. José A López-Bueno. Providing and Analysis of data; Elaboration and revision of the manuscript. Dante Culqui. Epidemiological study design. Elaboration and revision of the manuscript. César Asensio. Providing and Analysis of data; Elaboration and revision of the manuscript. Gerardo Sánchez-Martínez. Epidemiological study design. Elaboration and revision of the manuscript. Cristina Linares. Original idea of the study. Study design; Elaboration and revision of the manuscript.

Declaration of competing interest

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

Acknowledgements

The authors gratefully acknowledge ENPY 221/20 project grant from the Carlos III Institute of Health.

References

- AEMET . 2020. Atlas climático de España.http://www.aemet.es/es/serviciosclimaticos/datosclimatologicos/atlas_climatico [Google Scholar]

- Aena . 2020. Web AENA, Emisiones Acústica del aeropuerto de Madrid barajas.http://www.aena.es/es/aeropuerto-madrid-barajas/sirma-mapa-terminales.html [Google Scholar]

- Ahmadi M., Sharifi A., Dorosti S., Ghoushchi S.J., Ghanbari N. Investigation of effective climatology parameters on COVID-19 outbreak in Iran. Sci. Total Environ. 2020;729:138705. doi: 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2020.138705. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aich P., Potter A.A., Griebel P.J. Modern approaches to understanding stress and disease susceptibility: are view with special emphasis on respiratory disease. Int. J. Gen. Med. 2009;30:19–32. doi: 10.2147/ijgm.s4843. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arentz M., Yim E., Klaff L., et al. Characteristics and outcomes of 21 critically Ill patients with COVID‐19 in Washington State. J. Am. Med. Assoc. 2020;323(16):1612–1614. doi: 10.1001/jama.2020.4326. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Asensio C., Pavón I., de Arcas G., Asensio C., et al. Changes in noise levels in the city of Madrid during COVID-19 lockdown in 2020. J. Acoust. Soc. Am. 2020 Sep;148(3):1748. doi: 10.1121/10.0002008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barceló M.A., Varga D., Tobías A., Díaz J., Linares C., Sáez M. Long term effects of traffic noise on mortality in the city of Barcelona, 2004-2007. Environ. Res. 2016;147:193–206. doi: 10.1016/j.envres.2016.02.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- BOE . 2007. Boletín Oficial del Estado de 16 de noviembre de.https://www.boe.es/buscar/pdf/2007/BOE-A-2007-19744-consolidado.pdf [Google Scholar]

- BOE . 2020. Boletín Oficial del Estado 14 de marzo de 2020.https://www.boe.es/diario_boe/txt.php?id=BOE-A-2020-3692 Real Decreto 463/2020. [Google Scholar]

- Bontempi E. First data analysis about possible COVID-19 virus airborne diffusion due to air particulate matter (PM): the case of Lombardy (Italy) Environ. Res. 2020;186:109639. doi: 10.1016/j.envres.2020.109639. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- CDC . 2020. Coronavirus Disease 2019 (COVID-19): Frequently Asked Questions.https://www.cdc.gov/coronavirus/2019-ncov/faq.html [Google Scholar]

- CEBM Effect of latitude on COVID-19. 2020. https://www.cebm.net/covid-19/effect-of-latitude-on-covid-19/ Available online at:

- Chu C.M., Poon L.L., Cheng V.C., Chan K.S., Hung I.F., Wong M.M., et al. Initial viral load and the outcomes of SARS. CMAJ (Can. Med. Assoc. J.) 2004 Nov 23;171(11):1349–1352. doi: 10.1503/cmaj.1040398. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coccia M. Factors determining the diffusion of COVID-19 and suggested strategy to prevent future accelerated viral infectivity similar to COVID-19. Sci. Total Environ. 2020;729:138474. doi: 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2020.138474. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Comunian S., Dongo D., Milani C., Palestini P. Air pollution and covid-19: the role of particulate matter in the spread and increase of covid-19's morbidity and mortality. Int. J. Environ. Res. Publ. Health. 2020 Jun 22;17(12):4487. doi: 10.3390/ijerph17124487. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- de Madrid Ayuntamiento. 2020. Web Ayuntamiento de Madrid, Contaminación acústica, datos históricos diarios.https://datos.madrid.es [Google Scholar]

- Dkv-Gaes . 2015. III Informe Ruido Y Salud DKV-GAES.https://www.actasanitaria.com/documentos/iii-informe-ruido-y-salud-dkv-gaes/ [Google Scholar]

- Domigo J.L., Rovira J. Effects of air pollutants on the transmission and severity of respiratory viral infections. Environ. Res. 2020;187:109650. doi: 10.1016/j.envres.2020.109650. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dutheil F., Baker J.S., Navel V. COVID‐19 and cardiovascular risk: flying toward a silent world? J. Clin. Hypertens. 2020 doi: 10.1111/jch.14019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Elliott P., Savitz D.A. Design issues in small-area studies of environment and health. Environ. Health Perspect. 2008;116(8):1098–1104. doi: 10.1289/ehp.10817. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eze I.C., Foraster M., Schaffner E., Vienneau D., Héritier H., Rudzik F., Thiesse L., Pieren R., Imboden M., von Eckardstein A., Schindler C., Brink M., Cajochen C., Wunderli J.-M., Röösli M., Probst-Hensch N. Long-term exposure to transportation noise and air pollution in relation to incident diabetes in the SAPALDIA study. Int. J. Epidemiol. 2017 Aug;46(4):1115–1125. doi: 10.1093/ije/dyx020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frontera A., Cianfanelli L., Vlachos K., Landoni G., Cremona J. Severe air pollution links to higher mortality in COVID-19 patients: the "double-hit" hypothesis. J. Infect. 2020 doi: 10.1016/j.jinf.2020.05.031. 0163-4453. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Greene W.H. eighth ed. Pearson; Boston, London: 2018. Econometric Analysis. (Chapter 5) [Google Scholar]

- Holtmann, M., Jones, M., Shah, A., Holtmann, G., Low ambient temperatures are associated with more rapid spread of COVID-19 in the early phase of the endemic, Environ. Res., 10.1016/j.envres.2020.109625. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Hu Y., Sun J., Dai Z., et al. Prevalence and severity of corona virus disease 2019 (COVID‐19): a systematic review and meta‐analysis. J. Clin. Virol. 2020;127:104371. doi: 10.1016/j.jcv.2020.104371. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Irwin M.R. Sleep and infectious disease risk. Sleep. 2012 Aug 1;35(8):1025–1026. doi: 10.5665/sleep.1976. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Islam N., Shabnam S., Erzurumluoglu A.M. Temperature, humidity, and wind speed are associated with lower Covid-19 incidence. medRxiv. 2020 [Google Scholar]

- ISO 1996-2:2017 . International Organization of Standards; Geneva, Switzerland: 2017. Description, Measurement and Assessment of Environmental Noise. Part 2: Determination of Sound Pressure Levels. [Google Scholar]

- Lauer S.A., Grantz K.H., Bi Q., Jones F.K., Zheng Q., Meredith H.R., Azman A.S., Reich N.G., Lessler J. The incubation period of coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) from publicly reported confirmed cases: estimation and application. Ann. Intern. Med. 2020 May 5;172(9):577–582. doi: 10.7326/M20-0504. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Linares C., Díaz J. Impacto de la contaminación acústica urbana sobre la salud. Viure en Salut. 2007;74:4–5. [Google Scholar]

- Linares C., Díaz J. Ruido de tráfico y enfermedades respiratorias: ¿Hay evidencias? Arch. Bronconeumol. 2019 doi: 10.1016/j.arbres.2019.03.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Linares C., Belda F., López-Bueno J.A., Luna M.Y., Sánchez-Martínez G., Hervella B., Culqui D., Díaz J. Short-term effect of air pollution and meteorological variables on the incidence and severity of COVID-19 during the state of alarm in Spain: the case of Madrid. Environ. Res. 2021 doi: 10.1186/s12302-021-00548-1. (Press) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lipsitch M. DPhil seasonality of SARS-CoV-2: will COVID-19 go away on its own in warmer weather? Center for communicable disease dynamics. Harvard T.H. Chan School of Public Health. 2020 https://ccdd.hsph.harvard.edu/will-covid-19-go-away-on-its-own-in-warmer-weather/ [Google Scholar]

- Majde J.A., Krueger J.M. Links between the innate immune system and sleep. J. Allergy Clin. Immunol. 2005;116:1188–1198. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2005.08.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MITECO . 2020. Ministerio para la Transición Ecológica.https://www.miteco.gob.es/es/calidad-y-evaluacion-ambiental/temas/atmosfera-y-calidad-del-aire/calidad-del-aire/evaluacion-datos/fuentes-naturales/Prediccion_episodios_2020.aspx [Google Scholar]

- MSCBS Ministerio de Sanidad, consumo y bienestar social. 2020. https://www.mscbs.gob.es/profesionales/saludPublica/ccayes/alertasActual/nCov/documentos/Actualizacion_122_COVID-19.pdf

- MSCBS Ministerio de Sanidad, consumo y bienestar social. 2020. https://www.mscbs.gob.es/profesionales/saludPublica/ccayes/alertasActual/nCov/documentos/20200417_ITCoronavirus.pdf

- Navares R., Aznarte J.L., Linares C., Díaz J. Direct assessment of health impact from traffic intensity. Environ. Res. 2020;184(C):109254. doi: 10.1016/j.envres.2020.109254. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ogen Y. Assessing nitrogen dioxide (NO2) levels as contributing factor to coronavirus (COVID-19) fatality. Sci. Total Environ. 2020 doi: 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2020.138605. 0048-9697. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pequeno P., Mendel B., Rosa C., Bosholn M., Souza J.L., Baccaro F., Barbosa R., Magnusson W. Air transportation, population density and temperature predict the spread of COVID-19 in Brazil. PeerJ. 2020;8 doi: 10.7717/peerj.9322. 2020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pirrera S., De Valck E., Cluydts R. Nocturnal road traffic noise: a review on its assessment and consequences on sleep and health. Environ. Int. 2010 Jul;36(5):492–498. doi: 10.1016/j.envint.2010.03.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pollán M., Pérez-Gómez B., Pastor-Barriuso R., Oteo J., Hernán M.A., Pérez-Olmeda M., et al. Prevalence of SARS-CoV-2 in Spain (ENE-COVID): a nationwide, population-based seroepidemiological Study. Lancet. 2020;396:535–544. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(20)31483-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Recio A., Linares C., Banegas J.R., Díaz J. Road traffic noise effects on cardiovascular, respiratory and metabolic health: an integrative model of biological mechanisms. Environ. Res. 2016;146:359–370. doi: 10.1016/j.envres.2015.12.036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Recio A., Linares C., Banegas J.R., Díaz J. Impact of road traffic noise on cause-specific mortality in Madrid (Spin) Sci. Total Environ. 2017;590–591:171–173. doi: 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2017.02.193. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Remuzzi A., Remuzzi G. COVID-19 and Italy: what next? Lancet. 2020 Apr 11;395:1225–1228. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(20)30627-9. 10231 Epub 2020 Mar 13. PMID: 32178769; PMCID: PMC7102589. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saez M., Tobías A., Barceló M.A. Effects of long-term exposure to air pollutants on the spatial spread of COVID-19 in Catalonia, Spain. Environ. Res. 2020;191:110177. doi: 10.1016/j.envres.2020.110177. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sajadi M.M., Habibzadeh P., Vintzileos A., Shokouhi S., Miralles-Wilhelm F., Amoroso A. March 5, 2020. Temperature, Humidity and Latitude Analysis to Predict Potential Spread and Seasonality for COVID-19.https://ssrn.com/abstract=3550308 Available at: SSRN: [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Setti L., Passarini F., G De Genari G., et al. 2020. The Potential Role of Particulate Matter in the Spreading of COVID-19 in Northern Italy: First Evidence-Based Research Hypotheses BMJ. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sood A., Assad N.A., Barnes P.J., Churg A., Gordon S.B., Harrod K.S., et al. ERS/ATS workshop report on respiratory health effects of household air pollution. Eur. Respir. J. 2018 Jan 4;51(1):1700698. doi: 10.1183/13993003.00698-2017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tobías A., Molina T. Is temperature reducing the transmission of COVID-19? Environ. Res. 2020;186:109553. doi: 10.1016/j.envres.2020.109553. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tobías A., Díaz J., Sáez M., Alberdi J.C. Use of Poisson regression and box jenkins models to evaluate the short-term effects of environmental noise levels on health in Madrid, Spain. Eur. J. Epidemiol. 2001;17:765–771. doi: 10.1023/a:1015663013620. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tobías A., Recio A., Díaz J., Linares C. Health impact assessment of traffic noise. Environ. Res. 2015;137:136–140. doi: 10.1016/j.envres.2014.12.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tobías A., Díaz J., Recio A., Linares C. Traffic noise and risk of mortality from diabetes. Acta Diabetol. 2015;52:187–188. doi: 10.1007/s00592-014-0593-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Trefler S., Rodríguez A., Martín-Loeches I., Sanchez V., Marín J., Llauradó M., et al. Oxidative stress in immunocompetent patients with severe community-acquired pneumonia. A pilot study. Med. Intensiva. 2014;38:73–82. doi: 10.1016/j.medin.2013.01.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Van Kempen E., Casas M., Pershagen G., Foraster M. WHO environmental noise guidelines for the European Region: a systematic review on environmental noise and cardiovascular and metabolic effects: a summary. Int. J. Environ. Res. Publ. Health. 2018;15(2) doi: 10.3390/ijerph15020379. http://www.mdpi.com/1660-4601/15/2/379/htm pii: E379 ( [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Verity R., Okell L.C., Dorigatti I., Winskill P., Whittaker C., Imai N., et al. Estimates of the severity of coronavirus disease 2019: a model-based analysis. Lancet Infect. Dis. 2020 Jun;20;(6):669–677. doi: 10.1016/S1473-3099(20)30243-7. Epub 2020 Mar 30. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Villeneuve P.J., Goldberg M.S. Methodological considerations for epidemiological studies of air pollution and the SARS and COVID-19 coronavirus outbreaks. Environ. Health Perspect. 2020;128(9) doi: 10.1289/EHP7411. Published 2020 Sep. 9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- WHO. World Health Organization Media briefing WHO 03 august 2020. 2020. https://www.tododisca.com/oms-tasa-letalidad-coronavirus-alta/

- WHO. World Health Organization. Regional . Copenhagen; 2018. Office for Europe. Environmental Noise Guidelines for the European Regio. [Google Scholar]

- Yao Y., Pan J., Wang W., Liu Z., et al. Association of particulate matter pollution and case fatality rate of COVID-19 in 49 Chinese cities. Sci. Total Environ. 2020 doi: 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2020.140396. 0048-9697. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhou F., Yu T., Du R., Fan G., Liu Y., Liu Z., Xiang J., Wang Y., Song B., Gu X., Guan L., Wei Y., Li H., Wu X., Xu J., Tu S., Zhang Y., Chen H., Cao B. Clinical course and risk factors for mortality of adult inpatients with COVID-19 in Wuhan, China: a retrospective cohort study. Lancet. 2020 Mar 28;395:1054–1062. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(20)30566-3. 10229. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zoran MA, Savastru RS, Savastru DM, Tautan MN. Assessing the Relationship between Surface Levels of PM2.5 and PM10 Particulate Matter Impact on COVID-19 in Milan, Italy. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]