Graphical abstract

Central illustration. Impact of coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) on adult cardiac surgery activity.

Keywords: COVID-19, Adult cardiac surgery, Public health

Abbreviations: COVID-19, coronavirus disease 2019; EuroSCORE, European System for Cardiac Operative Risk Evaluation; ICU, intensive care unit; SARS-CoV-2, severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2; SFCTCV, French Society of Thoracic and Cardiovascular Surgery (Société française de chirurgie thoracique et cardiovasculaire)

Abstract

Background

The coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) outbreak had a direct impact on adult cardiac surgery activity, which systematically necessitates a postoperative stay in intensive care.

Aim

To study the effect of the COVID-19 lockdown on cardiac surgery activity and outcomes, by making a comparison with the corresponding period in 2019.

Methods

This prospective observational cohort study compared adult cardiac surgery activity in our high-volume referral university hospital from 9 March to 10 May 2020 versus 9 March to 10 May 2019. Data were collected in our local certified database and a national database sponsored by the French society of thoracic and cardiovascular surgery. The primary study endpoints were operative mortality and postoperative complications.

Results

With 105 interventions in 2020, our activity dropped by 57% compared with the same period in 2019. Patients were at higher risk, with a significantly higher EuroSCORE II score (3.8 ± 4.5% vs. 2.0 ± 1.8%; P < 0.001) and higher rates of active endocarditis (7.6% vs. 2.9%; P = 0.047) and recent myocardial infarction (9.5% vs. 0%; P < 0.001). The weight and priority of the interventions were significantly different in 2020 (P = 0.019 and P < 0.001, respectively). The rate of acute aortic syndromes was also significantly higher in 2020 (P < 0.001). Operative mortality was higher during the lockdown period (5.7% vs. 1.7%; P = 0.038). The postoperative course was more complicated in 2020, with more postoperative bleeding (P = 0.003), mechanical circulatory support (P = 0.032) and prolonged mechanical ventilation (P = 0.005). Only two patients (1.8%) developed a positive status for severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 after discharge.

Conclusions

Adult cardiac surgery was heavily affected by the COVID-19 lockdown. A further modulation plan is necessary to improve outcomes and reduce postponed operations to decrease operative mortality and morbidity.

Résumé

Contexte

L’épidémie de la COVID-19 a impacté sérieusement l’activité de chirurgie cardiaque adulte.

Objectif

Pour étudier l’impact et les résultats de cette crise sur notre activité chirurgicale pendant la durée du confinement en France, par rapport à l’année précédente.

Méthodes

Étude prospective observationnelle monocentrique, comparant l’activité de chirurgie cardiaque adulte du 09/03 au 10/05/2020 à la même période en 2019, dans une région épargnée lors de la première vague de la pandémie. Les données ont été saisies dans notre base de données locale, ainsi que dans la base de données nationale EPICARD, de la Société française de chirurgie thoracique et cardiovasculaire. Le critère de jugement principal était la mortalité opératoire.

Résultats

Avec 105 interventions, notre activité a chuté de 57 % par rapport à l’année précédente. Les patients étaient à plus haut risque opératoire, estimé par l’EuroSCORE II (3,8 ± 4,5 % vs 2,0 ± 1,8 % ; p < 0,001), avec un plus haut taux d’endocardites actives opérées (7,6 % vs 2,9 % ; p = 0,047) et significativement plus d’infarctus du myocardes récents (p < 0,001). Le type des interventions, ainsi que leur degré d’urgence, étaient significativement différents cette année (p = 0,019 et p < 0,001, respectivement). Le taux de syndromes aortiques aigus était plus important (p < 0,001) pour cette même période. La mortalité opératoire a été plus importante (5,7 % vs 1,7 % ; p = 0,038). Les patients ont saigné davantage en postopératoire (p = 0,003), ont nécessité davantage une ventilation invasive (p = 0,032) et pour une plus longue durée (p = 0,005). Seulement deux patients ont contracté la COVID-19 (1,8 %) après la sortie de l’hôpital.

Conclusions

La réduction de la morbi-mortalité de la chirurgie cardiaque adulte en période de pandémie nécessite un plan de modulation propre à cette activité chirurgicale spécialisée.

Mots clés: COVID-19, Chirurgie cardiaque adulte, Santé publique

Background

With more than 80 million patients tested positive to date and more than 2,000,000 global deaths [1], coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19), caused by infection with the novel severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2), has been declared a global pandemic by the World Health Organisation. Since the emergence of this virus in December 2019 in Wuhan (China) [2], it has spread quickly worldwide. At the time of writing, France was the eleventh country in the world by absolute number of confirmed cases (n = 266,040) [1]. Drastic measures were taken by different countries to prevent local health infrastructures being overwhelmed and the ensuing increased mortality in high-risk patients. In France, national lockdown was declared by the government for a total of 8 weeks, starting on 17 March 2020. All hospitals and clinics were asked to modify their intensive care unit (ICU) capacities, and to be ready for any surge in critically ill patients requiring advanced respiratory support.

Cardiac surgery systematically requires postoperative intensive care. As these specialised units were reserved for patients with COVID-19 necessitating respiratory support, elective open-heart surgeries were substantially delayed in almost all French centres; this raised concerns about patient safety while on the waiting list. A careful risk/benefit evaluation is required for candidates for cardiac surgery, as hospitals have been identified as the main sites of SARS-CoV-2 viral transmission, and cardiac comorbidity is associated with a more severe course of the disease.

The scientific committee and directory board of the French society of thoracic and cardiovascular surgery (Société française de chirurgie thoracique et cardiovasculaire [SFCTCV]) announced, starting on 17 March 2020, a guidance statement for triage of surgical candidates during this COVID-19 pandemic. This system is based on a “three-colour” stratification of patients on the waiting list (Table 1 ), corresponding to recommended delays to surgical treatment in the pandemic context. Other experts in cardiology and cardiothoracic surgery published similar recommendations in their respective countries, with patient admission and management purposes [3], [4], [5], [6].

Table 1.

French society for thoracic and cardiovascular surgery (SFCTCV) guidelines for the management of cardiac surgery candidates.

| Category | Clinical condition | Delay |

|---|---|---|

| Emergency | Any patient admitted for: | Immediate |

| – acute aortic dissection | ||

| – acute refractory cardiogenic shock necessitating salvage or emergent intervention | ||

| Red | Syncopal aortic stenosis | < 15 days |

| Ascending aortic aneurysm > 60 mm | ||

| Left-sided highly embolic cardiac tumour | ||

| Acute coronary syndrome with surgical indication | ||

| Active infective endocarditis | ||

| Orange | Left-sided valve disease with at least one among: | 2–4 weeks |

| – LVEF < 50% | ||

| – SPAP > 60 mmHg | ||

| – furosemide treatment > 120 mg/day | ||

| Left main disease or any chronic stable coronary disease necessitating surgical treatment | ||

| Any surgical cardiac disease with a decreased functional status since the initial report | ||

| Green | Any surgical cardiac disease for which a greater delay might worsen the final outcome | > 4 weeks |

Each category was assigned a maximum period of time for intervention. LVEF: left ventricular ejection fraction; SPAP: systolic pulmonary artery pressure; SFCRCV: Société française de chirurgie thoracique et cardiovasculaire.

Our aim was to evaluate the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic and the associated restrictive measures on the features and outcomes of cardiac surgical activity in a tertiary referral centre in France. Features and outcomes observed during the lockdown period (9 March to 10 May 2020) were compared with those in the corresponding time period in 2019. We discuss the relevant measures to prevent SARS-CoV-2 contamination, and their effect on the population of cardiac surgery recipients and on clinical results.

Methods

Epidemic situation and context

Our centre is located in the Brittany region of France (with a population of around 3,329,000 inhabitants) and was identified as the regional reference for management of SARS-CoV-2 positive cases. In this western part of the country, the incidence of COVID-19 was lower than in eastern regions. The first French cluster was identified in the eastern city of Mulhouse, where a communitarian meeting took place in February 2020 with more than 2500 people and was identified as a major spreader event. In Brittany, the first cluster was identified in a southern county of the region. The peak of COVID-19 admissions was predicted to occur in France and in Brittany between 30 March and 6 April 2020 [7]. With the ensuing national lockdown, unauthorised travel throughout the entire country was prohibited, and closure of almost all commodities and collective services was imposed. A national emergency plan was declared, and all university hospitals and tertiary healthcare facilities were asked to prepare for any surge of patients in urgent need of respiratory support to ICUs.

Before the start of the crisis, our cardiothoracic surgery department entailed 17 dedicated ICU beds and eight post-interventional care beds. From 12 March 2020, these units were mandated to function as polyvalent intensive care facilities; they received patients requiring urgent non-cardiac surgery, trauma patients and cases requiring medical intensive care, with the other ICUs within the hospital being dedicated to managing patients infected with SARS-CoV-2. Therefore, the capacity to receive patients after cardiac surgery was significantly diminished compared with the pre-lockdown period.

We modified our operating schedule in accordance with national and scientific guidelines (Table 1). Patients who were scheduled for an intervention during the initial lockdown period had their procedure postponed for a minimum of 4 weeks. Each postponed patient was accorded a priority degree according to the SFCTCV recommendations. Surgeons conducted telephone interviews with their patients, and assessed the risks associated with postponement of cardiac surgery. Telephone interviews were repeated 3 weeks later, to make a new evaluation of the clinical status of the patients on the waiting list, and to potentially reclassify them according to the SFCTCV guidelines.

Study design

We conducted a prospective single-centre study of cardiac surgery activity in our Cardiothoracic and vascular surgery department, which is among the top five centres in France, performing more than 1300 open-heart surgeries per year. All data pertaining to cardiac surgery recipients in our department (including, pre-, intra- and postoperative data until hospital discharge) are prospectively collected within the SFCTCV national database “EPICARD”. This database has been modified since the COVID-19 crisis in France to include any known COVID-19 test results or related clinical symptoms before admission, as well as whether postponement of the intervention, was required with respect to the initial schedule because of the pandemic situation. Additionally, the same data are entered into a local prospective database, registered in the National Committee for Informatics and Freedom (Commission nationale de l’informatique et des libertés [CNIL]) archive under the number 1207754. Both databases are approved by local and national ethic boards. Operative mortality and morbidity were defined as occurring within the 30th postoperative day, or later if during the same hospitalisation. The European system for cardiac operative risk evaluation (EuroSCORE) II score was obtained for all patients according to the calculator available online at www.euroscore.org.

Patients were followed up after discharge, for up to 2 months. A telephone interview was carried out in June 2020, and information about the post-discharge course was recorded; this included out-of-hospital mortality, morbidity and clinically/biologically confirmed infection with SARS-CoV-2 virus, occurring up to 2 months after cardiac surgery.

The primary study endpoints were in-hospital mortality and postoperative complications among cardiac surgery recipients during the period from 9 March to 10 May 2020. Secondary endpoints were 30-day survival and COVID-19 status during or after the hospital stay. All outcome measures were compared with those observed one year earlier, during the period from 9 March to 10 May 2019.

Statistical analysis

Continuous data are presented as means ± standard deviations or as medians if not normally distributed. Categorical data are presented as counts and percentages. Intergroup comparison was performed using the two-tailed Student's t-test and the Mann–Whitney U test. The alpha level was 0.05. Analyses were conducted using the statistical package for social sciences (SPSS) software for Windows (IBM, Armonk, NY, USA).

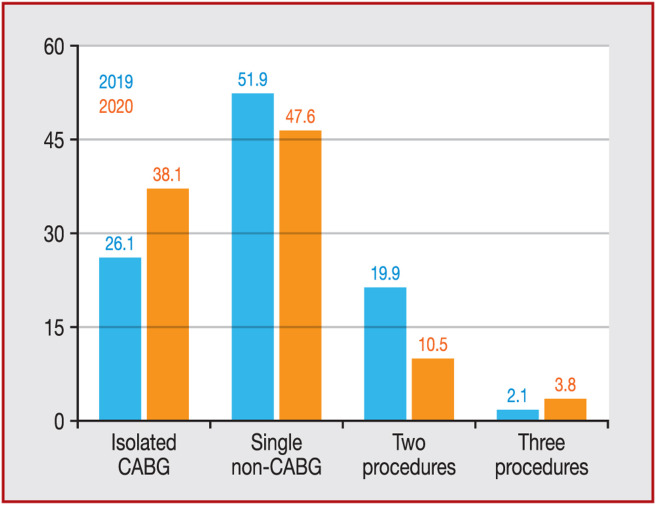

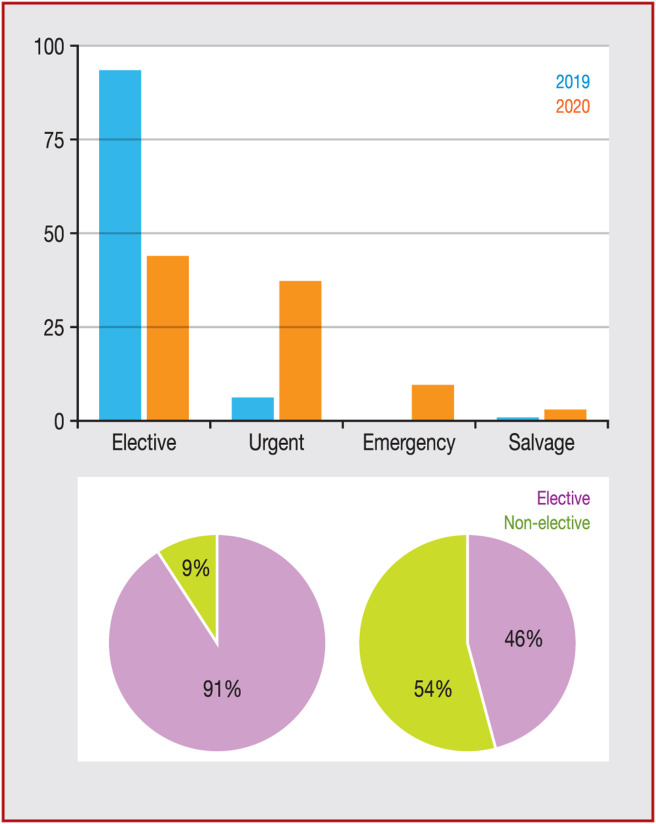

Results

During the period from 9 March to 10 May 2020, 105 patients underwent cardiac surgery in our department, representing a 57% drop compared with the same period in 2019 (105 vs. 242 patients). Seventy-nine patients were male (75%) and the mean age was 66.2 ± 10.8 years. The baseline characteristics of patients in the 2020 cohort are presented in Table 2 and are compared with the 2019 patient group. Mean body mass index was significantly lower compared with the 2019 cohort, (P < 0.001), whereas preoperative creatinine clearance was significantly greater in the 2020 cohort (86.6 ± 39.1 vs. 64.7 ± 27.9 mL/min; P < 0.001). Also, the mean preoperative EuroSCORE II score was significantly higher in 2020 (3.8 ± 4.5% vs. 2.0 ± 1.8%; P < 0.001). Concordantly, activity in 2020 was characterised by statistically higher rates of active endocarditis (7.6% vs. 2.9%; P = 0.047) recent acute myocardial infarction (9.5% vs. 0%; P < 0.001) and patients admitted with a critical preoperative status (preoperative administration of inotropes and/or circulatory mechanical support) (P < 0.001). The distribution of weight of interventions (as defined by EuroSCORE II) (Fig. 1 ) and their priorities were significantly different between cohorts (P = 0.019 and P < 0.001, respectively). The 2020 activity entailed a significantly higher rate of urgent/emergency cases (Fig. 2 ). Both the rate and absolute number of non-elective cases were higher in 2020 (Table 2). The rate of acute aortic syndromes (including aortic dissection, intramural hematoma and penetrating aortic ulcer) receiving non-elective surgical treatment was also significantly greater in 2020 (P < 0.001) (Table 2).

Table 2.

Baseline patient characteristics.

| 2019 | 2020 | P | |

|---|---|---|---|

| (n = 242) | (n = 105) | ||

| Preoperative | |||

| Age (years) | 67 ± 13.2 | 66.2 ± 10.8 | 0.57 |

| Male sex | 162 (66.9) | 79 (75.2) | 0.12 |

| Body surface area (m2) | 1.87 ± 0.23 | 1.92 ± 0.23 | 0.08 |

| Body mass index (kg/m) | 35.6 ± 9.3 | 27 ± 5.3 | < 0.001 |

| Preoperative creatinine (μmol/L) | 88.5 ± 61.9 | 95.4 ± 76.1 | 0.38 |

| Creatinine clearance (mL/min) | 64.7 ± 27.9 | 86.6 ± 39.1 | < 0.001 |

| LVEF (%) | 60.3 ± 10.8 | 58.2 ± 13.6 | 0.13 |

| SPAP (mmHg) | 31.3 ± 7.9 | 30.1 ± 10.1 | 0.25 |

| Active infectious endocarditis | 7 (2.9) | 8 (7.6) | 0.047 |

| Acute aortic syndrome | 1 (0.4) | 9 (8.6) | < 0.001 |

| Recent AMI | 0 (0) | 10 (9.5) | < 0.001 |

| Critical preoperative state | 0 (0) | 11 (10.5) | < 0.001 |

| EuroSCORE II score (%) | 2.0 ± 1.8 | 3.8 ± 4.5 | < 0.001 |

| Priority | < 0.001 | ||

| Elective | 221 (91.3) | 48 (45.7) | |

| Urgent | 20 (8.3) | 41 (39) | |

| Emergency | 0 (0) | 12 (11.4) | |

| Salvage | 1 (0.4) | 4 (3.8) |

Data are expressed as mean ± standard deviation or number (%). AMI: acute myocardial infarction; EuroSCORE: European System for Cardiac Operative Risk Evaluation; LVEF: left ventricular ejection fraction; SPAP: systolic pulmonary artery pressure.

Figure 1.

Distribution of intervention rates by their weight, according to the European system for cardiac operative risk evaluation (EuroSCORE) II classification, expressed as percentages. CABG: coronary artery bypass grafting.

Figure 2.

Distribution of intervention priorities (%) according to the European system for cardiac operative risk evaluation (EuroSCORE) II classification. Pie charts: intervention priorities classified by elective versus non-elective cases.

Operative mortality was significantly higher during the lockdown period (5.7% vs. 1.7%; P = 0.038). One of the patients who died was operated on for a post-infarction ventricular septal defect, after documented SARS-CoV-2 infection 2 weeks earlier; he died later of myocardial failure. Complications occurred more frequently in 2020 (in 44.8% vs. 9.9% of patients; P < 0.001) (Table 3 ), including postoperative bleeding (P = 0.003), mechanical support, such as an intra-aortic balloon pump (P = 0.032) or extracorporeal life support (P = 0.006), prolonged mechanical ventilation (P = 0.005) and reintubation (P = 0.008). We did not observe any significant difference in postoperative pulmonary infections (P = 0.70) or mediastinitis (P = 0.17). One patient was transplanted, and two patients were implanted with a long-term mechanical circulatory support device. Five patients underwent transcatheter aortic valve implantation. Postoperative stay was shorter in 2020 (10.1 vs. 11 days).

Table 3.

Intra- and postoperative outcomes.

| 2019 | 2020 | P | |

|---|---|---|---|

| CPB time (minutes) | 86.6 ± 47.6 | 115.2 ± 103.2 | 0.001 |

| CC time (minutes) | 73.2 ± 30.4 | 82.0 ± 36.3 | 0.029 |

| Any complication | 24 (9.9) | 47 (44.8) | < 0.001 |

| Postoperative bleeding | 7 (2.9) | 11 (10.5) | 0.003 |

| IABP | – | 2 (1.9) | 0.032 |

| ECLS | 3 (1.2) | 7 (6.7) | 0.006 |

| Prolonged intubation | 4 (1.7) | 8 (7.6) | 0.005 |

| Reintubation | – | 3 (2.9) | 0.008 |

| Pulmonary infection | 14 (5.8) | 5 (4.8) | 0.70 |

| Mediastinitis | 1 (0.4) | 2 (1.9) | 0.17 |

| Stroke | 4 (1.7) | 1 (1) | 0.62 |

| AKI with dialysis | 3 (1.2) | 4 (3.8) | 0.12 |

| Operative mortality | 4 (1.7) | 6 (5.7) | 0.038 |

Data are expressed as mean ± standard deviation or number (%). AKI: acute kidney injury; CC: cross-clamp; CPB: cardiopulmonary bypass; ECLS: extracorporeal life support; IABP: intra-aortic balloon pump.

Two patients (1.8%), both of whom were operated on before 16 March 2020, developed SARS-CoV-2 infection following their cardiac operation; they were discharged home, and were alive at the 2-month follow-up.

Finally, five patients on the waiting list died after their operation was postponed. Three of these patients were initially scheduled for coronary artery bypass grafting for three-vessel disease; the other two were waiting for carotid transcatheter aortic valve replacement. The causes of death among these patients were sudden cardiac death and refractory cardiac failure.

Discussion

The potentially detrimental effects of the COVID-19 outbreak on the management of patients affected by cardiac disease with surgical indication was foreseen by the middle of April 2020 [5]. We present the first detailed analysis of adult cardiac surgery activity during the COVID-19 lockdown period in a tertiary referral centre, including a comparison with activity during the same period in 2019. Given the life-threatening nature of cardiac diseases with surgical indication, dedicated planning of healthcare system resources will be required in the context of a COVID-19 second wave or other outbreaks. These original data underline the priority that should be attributed to the cardiac surgery department resuming elective activity, and substantiates previous recommendations [8]. The current observations were obtained from a country in Western Europe that was affected by the pandemic before other regions of the world, where earlier epidemiological phases are currently being experienced.

At the time of writing, France was the eleventh country in the world by number of confirmed COVID-19 cases. Nonetheless, significant imbalances existed between regions with respect to the number of confirmed cases; the western part of the country, where our hospital is located, was characterised by a remarkably lower incidence. The national emergency plan entailed transfer of critical patients from other regions of the country to our hospital. Hence, as a result of the shortage of ICU beds and ventilators, our cardiac surgical activity dropped by 57%. Patients were mainly admitted for urgent or emergency intervention (patients who had not had a previous intervention and were not classified according to the SFCTCV recommendations) and had an overall more severe risk profile at admission. Non-elective indications occurred not only with a significantly higher rate than in 2019, but their absolute number was also markedly greater than one year previously (Central illustration). Concordantly, the operative mortality and morbidity rates were significantly higher versus those observed in 2019. It can therefore be expected that the average hospital resource consumption per patient will be greater than for the corresponding 2019 period. Several factors can be proposed to explain these observations. The postponement of scheduled surgery for severe coronary or valvular disease exposes patients to a time-incremental risk of decompensation and admission in more critical conditions. Admissions to cardiology departments have decreased during the crisis [9], [10], thus limiting the capacity for diagnosis and exploration of heart disease. Finally, SARS-CoV-2 has a tropism for the cardiovascular system, and its role in accelerating or destabilising cardiovascular diseases is not fully understood [11]. Therefore, the organisation of healthcare services should entail identification of reference cardiac surgery centres with sufficient resources to manage a surge in non-elective and more complex cases during similar outbreak settings, including a second COVID-19 wave, with or without institution of a second lockdown. Such organisation should be orchestrated at a national level and modulated on a regional basis, depending on differential degrees of viral circulation in individual regions.

In our series, two cardiac surgery patients (1.8%) developed a SARS-CoV-2 positive status after their cardiac operation. After the institution of separate hospital pathways for patients with a SARS-CoV-2 positive status during the earliest phases of the lockdown period, no additional cases of SARS-CoV-2 infection occurred among patients operated on after 16 March 2020. A “one room–one patient” strategy and the rigorous selection of candidates by surgical priority (Table 1) were part of the institutional protocols to minimise the risk of nosocomial SARS-CoV-2 spread in this population.

Our study has some limitations; the short time period was perhaps a major confounding factor.

Conclusions

The COVID-19 pandemic heavily affected cardiac surgery activity, with an increased incidence of urgent/emergency cases, resulting in a higher rate of postoperative adverse events. Facing the risk of a second COVID-19 wave, a resource modulation plan should be developed to decrease the rate of postponed operations and to allow selected centres to manage relevant non-elective and complex surgical candidates.

Disclosure of interest

The authors declare that they have no competing interest.

Acknowledgments

The authors are thankful to Dr Calixte De La Bourdonnaye, Mrs Melanie Allainmat and Mrs Sylvie Marie for their invaluable help in data gathering and management.

Footnotes

Our experience in adult cardiac surgery activity during the French lockdown period. More emergent patients and higher mortality rate compared to the results a year earlier. Cardiac surgery should be preserved during lockdown periods, to avoid increased cardiovascular mortality.

References

- 1.Johns Hopkins University & Medicine. Coronavirus Resource Centre. Available at: https://coronavirus.jhu.edu.

- 2.Zhu N., Zhang D., Wang W., et al. A novel coronavirus from patients with pneumonia in China, 2019. N Engl J Med. 2020;382:727–733. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa2001017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Belluschi I., De Bonis M., Alfieri O., et al. First reorganisation in Europe of a regional cardiac surgery system to deal with the coronavirus-2019 pandemic. Eur J Cardiothorac Surg. 2020 doi: 10.1093/ejcts/ezaa185. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bonalumi G., di Mauro M., Garatti A., et al. The COVID-19 outbreak and its impact on hospitals in Italy: the model of cardiac surgery. Eur J Cardiothorac Surg. 2020;57:1025–1028. doi: 10.1093/ejcts/ezaa151. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Chieffo A., Stefanini G.G., Price S., et al. EAPCI position statement on invasive management of acute coronary syndromes during the COVID-19 pandemic. Eur Heart J. 2020;41:1839–1851. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehaa381. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hassan A., Arora R.C., Adams C., et al. Cardiac surgery in Canada during the COVID-19 pandemic: a guidance statement from the Canadian Society of Cardiac Surgeons. Can J Cardiol. 2020;36:952–955. doi: 10.1016/j.cjca.2020.04.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Massonnaud C, Roux J, Crépey P. Forecasting short term hospital needs in France. Available at: https://sfar.org/covid-19-forecasting-short-term-hospital-needs-in-france/.

- 8.Chikwe J., Gaudino M., Hameed I., et al. Committee recommendations for resuming cardiac surgery activity in the SARS-CoV-2 era: guidance from an international cardiac surgery consortium. Ann Thorac Surg. 2020;110:725–732. doi: 10.1016/j.athoracsur.2020.05.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.De Rosa S., Spaccarotella C., Basso C., et al. Reduction of hospitalisations for myocardial infarction in Italy in the COVID-19 era. Eur Heart J. 2020;41:2083–2088. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehaa409. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Metzler B., Siostrzonek P., Binder R.K., Bauer A., Reinstadler S.J. Decline of acute coronary syndrome admissions in Austria since the outbreak of COVID-19: the pandemic response causes cardiac collateral damage. Eur Heart J. 2020;41:1852–1853. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehaa314. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Xiong T.Y., Redwood S., Prendergast B., Chen M. Coronaviruses and the cardiovascular system: acute and long-term implications. Eur Heart J. 2020;41:1798–1800. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehaa231. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]