Abstract

We report the emergence of an isolate belonging to the sequence type (ST)131-Escherichia coli high-risk clone with ceftazidime-avibactam resistance recovered from a patient with bacteremia in 2019. Antimicrobial susceptibility was determined and whole genome sequencing (Illumina-NovaSeq6000) and cloning experiments were performed to investigate its resistance phenotype. A KPC-3-producing E. coli isolate susceptible to ceftazidime-avibactam (MIC = 0.5/4 mg/L) and with non-wild type MIC of meropenem (8 mg/L) was detected in a blood culture performed at hospital admission. Following 10-days of standard ceftazidime-avibactam dose treatment, a second KPC-producing E. coli isolate with a phenotype resembling an extended-spectrum β-lactamase (ESBL) producer (meropenem 0.5 mg/L, piperacillin-tazobactam 16/8 mg/L) but resistant to ceftazidime-avibactam (16/4 mg/L) was recovered. Both E. coli isolates belonged to ST131, serotype O25:H4 and sublineage H30R1. Genomics analysis showed a core genome of 5,203,887 base pair with an evolutionary distance of 6 single nucleotide polymorphisms. A high content of resistance and virulence genes was detected in both isolates. The novel KPC-49 variant, an Arg-163-Ser mutant of blaKPC-3, was detected in the isolate with resistance to ceftazidime-avibactam. Cloning experiments revealed that blaKPC-49 gene increases ceftazidime-avibactam MIC and decreases carbapenem MICs when using a porin deficient Klebsiella pneumoniae strain as a host. Both blaKPC-3 and blaKPC-49 genes were located on the transposon Tn4401a as a part of an IncF [F1:A2:B20] plasmid. The emergence of novel blaKPC genes conferring decreased susceptibility to ceftazidime-avibactam and resembling ESBL production in the epidemic ST131-H30R1-E. coli high-risk clone presents a new challenge in clinical practice.

Keywords: ST131-H30R1-E. coli high-risk clone, ceftazidime-avibactam susceptibility, blaKPC-49, whole genome sequencing

1. Introduction

Global expansion of Escherichia coli sequence type 131 (ST131) among multidrug-resistant (MDR) Enterobacterales strains is a cause of great concern in Public Health. The ST131-E. coli clonal group associated with extended-spectrum-β-lactamase (ESBLs) production is the most frequent lineage among extraintestinal pathogenic E. coli (ExPEC) isolates [1,2]. The ST131 clone is part of the phylogenetic group B2 and predominantly corresponds to the O25b:H4 serotype [3]. The rapid and successful dissemination of the ST131 high-risk clone has been mainly attributed to the sublineage H30, defined by the presence of the specific fimbrial adhesin allele, fimH30 [4]. Within the H30 sublineage, two fluoroquinolone resistant clades have been widely identified causing human infections: clade 1 or H30R1 and clade 2 or H30Rx [4,5]. The ST131-H30R1-E. coli subclone has been additionally related to an extensive virulence profile [1,2] and with the production of ESBL enzymes, particularly CTX-M-27 (sublineage C1-M27) [6].

In Spain, KPC (Klebsiella pneumoniae carbapenemase) production among ST131-E. coli isolates has been scarcely reported [7]. KPC enzymes hydrolyze efficiently almost all β-lactam antibiotics, and older β-lactamase inhibitors such as clavulanic acid are ineffective to prevent β-lactam degradation. Mobilization and diffusion of blaKPC genes have been mostly linked to a conserved 10-kb Tn3-based transposon (Tn4401) and a wide variety of conjugative plasmids that frequently harbor resistance genes against other antimicrobial groups [8]. Infections caused by these MDR KPC-producing Enterobacterales isolates are usually difficult to treat and are frequently associated with high mortality and morbidity rates [9,10]. In February 2015, the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) approved the ceftazidime-avibactam combination as an alternative to carbapenems in patients with complicated intra-abdominal and urinary tract infections caused by MDR Gram-negative bacteria isolates [11]. Since then, several studies have demonstrated the in vivo efficacy of ceftazidime-avibactam in the treatment of infections caused by KPC-producers [12,13,14]. Moreover, a recent study has supported the presumptive use of ceftazidime-avibactam against carbapenem resistance E. coli isolates, including members of the ST131 lineage [15]. Nevertheless, the recent description of K. pneumoniae high-risk clones producing new KPC variants conferring resistance to ceftazidime-avibactam is a cause of great concern in the clinical setting [16,17,18].

The aim of this work was to describe the emergence of the novel KPC-49 variant conferring ceftazidime-avibactam resistance in an ST131-H30R1-E. coli isolate, with an ESBL resembled phenotype, recovered from an infected patient during the ceftazidime-avibactam treatment.

2. Results

2.1. Case Report

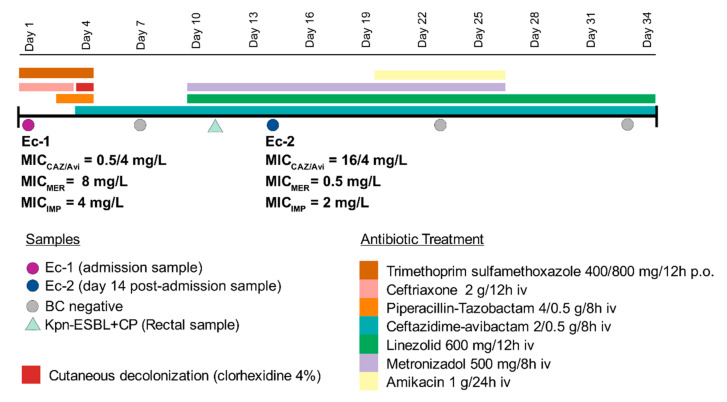

In April 2019, a 40–50 range age woman with a biliary cholangiocarcinoma was admitted at the Ramón y Cajal University Hospital (Madrid, Spain) with sepsis symptoms. Timeline of events during the hospital admission and antibiotic treatments received are represented in Figure 1. An E. coli isolate with an MDR phenotype consistent with carbapenemase production (Ec-1) was recovered at admission from a blood culture. Ec-1 showed non wild-type susceptibility to imipenem (MIC = 4 mg/L) and meropenem (MIC = 8 mg/L) and co-resistance to other antimicrobial groups, except ceftazidime-avibactam (MIC = 0.5/4 mg/L), tigecycline (MIC ≤ 0.5 mg/L), amikacin (MIC ≤ 8 mg/L), colistin (MIC ≤ 1 mg/L), and fosfomycin (MIC ≤ 32 mg/L) (Table 1). The eazyplex ®SuperBug CRE system demonstrated the presence of a blaKPC gene, and following the regional guidelines [19], the patient was placed under contact precautions in a single room.

Figure 1.

Timeline of events and antibiotic treatments received during the admission. CAZ/Avi = ceftazidime-avibactam; MER = meropenem; IMP = imipenem; BC = blood culture; Kpn = K. pneumoniae; p.o. = oral dosage; iv = intravenous.

Table 1.

Antimicrobial susceptibility results by broth microdilution and gradient strips for KPC-producing E. coli isolates (Ec-1 and Ec-2), KPC-producing E. coli transformants (pKPC-3-TM and pKPC-49-TM), the isogenic E. coli DH5α strain, KPC-producing K. pneumoniae transformants (pKPC-3-TM and pKPC-49-TM), and the SHV-5-producing K. pneumoniae CSUB10R strain (ΔompK35; ΔompK36; ΔompK37).

| Broth Microdilution (mg/L) (Interpretation) | Gradient Strips (mg/L) (Interpretation) | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Antimicrobials | Ec-1 | Ec-2 |

E. coli pKPC-3-TM |

E. coli pKPC-49-TM |

E. coli DH5α |

K. pneumoniae pKPC-3-TM | K. pneumoniae pKPC-49-TM | K. pneumoniae CSUB10R |

E. coli pKPC-3-TM |

E. coli pKPC-49-TM |

E. coli DH5α |

K. pneumoniae pKPC-3-TM | K. pneumoniae pKPC-49-TM | K. pneumoniae CSUB10R |

| Piperacillin-tazobactam | >64/4 (R) | 16/4 (I) | ≤4/4 (S) | ≤4/4 (S) | ≤4/4 (S) | >64/4 (R) | >64/4 (R) | >64/4 (R) | - | - | - | - | - | - |

| Ceftazidime | >32 (R) | >32 (R) | 1 (S) | 2 (I) | ≤0.25 (S) | >32 (R) | >32 (R) | >32 (R) | 0.25 (S) | 1 (S) | 0.19 (S) | >256 (R) | >256 (R) | >256 (R) |

| Cefotaxime | >32 (R) | >32 (R) | ≤0.25 (S) | ≤0.25 (S) | ≤0.25 (S) | >32 (R) | >32 (R) | >32 (R) | 0.032 (S) | 0.047 (S) | 0.032 (S) | >256 (R) | >256 (R) | >256 (R) |

| Cefepime | >64 (R) | 64 (R) | ≤0.125 (S) | 0.25 (S) | ≤0.125 (S) | >64 (R) | >64 (R) | 64 (R) | 0.047 (S) | 0.047 (S) | 0.023 (S) | >256 (R) | >256 (R) | 32 (R) |

| Aztreonam | >32 (R) | >32 (R) | 4 (I) | ≤0.5 (S) | ≤0.5 (S) | >32 (R) | >32 (R) | >32 (R) | - | - | - | - | - | - |

| Ceftazidime-avibactam | 0.5/4 (S) | 16/4 (R) | ≤0.125/4 (S) | ≤0.125/4 (S) | ≤0.125/4 (S) | 4/4 (S) | 4/4 (S) | 2/4 (S) | 0.047/4 (S) | 0.094/4 (S) | 0.094/4 (S) | 2/4 (S) | 12/4 (R) | 2/4 (S) |

| Imipenem | 4 (I) | 2 (S) | 0.5 (S) | ≤0.25 (S) | ≤0.25 (S) | >16 (R) | >16 (R) | 2 (S) | 0.25 (S) | 0.25 (S) | 0.38 (S) | >32 (R) | 4 (I) | 0.75 (S) |

| Meropenem | 8 (I) | 0.5 (S) | ≤0.125 (S) | ≤0.125 (S) | ≤0.125 (S) | 16 (R) | 8 (I) | 2 (S) | 0.023 (S) | 0.023 (S) | 0.032 (S) | 6 (I) | 2 (S) | 2 (S) |

| Gentamicin | >8 (R) | >8 (R) | ≤8 (S) | ≤8 (S) | ≤8 (S) | ≤8 (S) | ≤8 (S) | ≤8 (S) | - | - | - | - | - | - |

| Amikacin | ≤8 (S) | ≤8 (S) | ≤8 (S) | ≤8 (S) | ≤8 (S) | ≤8 (S) | ≤8 (S) | ≤8 (S) | - | - | - | - | - | - |

| Tobramycin | >8 (R) | >8 (R) | ≤8 (S) | ≤8 (S) | ≤8 (S) | ≤8 (S) | ≤8 (S) | ≤8 (S) | - | - | - | - | - | - |

| Ciprofloxacin | >2 (R) | >2 (R) | ≤2 (S) | ≤2 (S) | ≤2 (S) | >2 (R) | >2 (R) | >2 (R) | - | - | - | - | - | - |

| Tigecycline | ≤0.5 (S) | ≤0.5 (S) | ≤0.5 (S) | ≤0.5 (S) | ≤0.5 (S) | ≤0.5 (S) | ≤0.5 (S) | ≤0.5 (S) | - | - | - | - | - | - |

| Colistin | ≤2 (S) | ≤2 (S) | ≤2 (S) | ≤2 (S) | ≤2 (S) | ≤2 (S) | ≤2 (S) | ≤2 (S) | - | - | - | - | - | - |

| Fosfomycin | ≤32 (S) | ≤32 (S) | ≤32 (S) | ≤32 (S) | ≤32 (S) | >32 (S) | >32 (S) | >32 (S) | - | - | - | - | - | - |

At admission, the patient was treated with ceftriaxone (2 g/12 h iv) and trimethoprim sulfamethoxazole (400/800 mg/12 h po) during 3 and 4 days, respectively. Piperacillin-tazobactam (4/0.5 g/8 h iv) was also added between days 3 and 4. Treatment with ceftazidime-avibactam (2/0.5 g/8 h iv) was started on day 4 and was discontinued at discharge (after 30 days). On day 4, following the protocol of contact precautions, the patient’s skin was washed with a 4% soapy chlorhexidine antiseptic gel. On day 7, a sterile blood culture was recovered, but due to the recurrent fever, the antibiotic regimen was modified adding metronidazole (500 mg/8 h iv) and linezolid (600 mg/12 h iv) over ceftazidime-avibactam from day 10 to 27 (17 days) and to day 34 (24 days), respectively. On hospital day 12, a K. pneumoniae isolate with a phenotype compatible with KPC carbapenemase production was detected in a rectal culture. Unfortunately, this isolate was not preserved for subsequent analysis.

On day 14 post-admission, 10 days after the ceftazidime-avibactam treatment initiation, a second KPC-producing E. coli isolate (Ec-2) was recovered in a blood sample. This isolate (Ec-2) exhibited a phenotype compatible with an ESBL producer and showed an MIC reduction of 1-fold dilution to imipenem (MIC = 2 mg/L) and 4-fold dilutions to meropenem (MIC = 0.5 mg/L) with piperacillin-tazobactam in the susceptible, increased exposure category (I) (MIC = 16/4 mg/L). On the contrary, an increase of 5-fold dilutions to ceftazidime-avibactam MIC (16/4 mg/L) was observed compared to Ec-1 isolate. Moreover, Ec-2 remained susceptible to tigecycline (MIC ≤ 0.5 mg/L), amikacin (MIC ≤ 8 mg/L), colistin (MIC ≤ 1 mg/L) and fosfomycin (MIC ≤ 32 mg/L) (Table 1). The eazyplex ®SuperBug CRE system also confirmed the presence of a blaKPC in this isolate. On day 20, amikacin (500 mg/24 h iv) was administered until day 27 and blood cultures collected between days 23 and 33 were negative. Patient’s fever remitted and patient was discharged 34 days post-admission (Figure 1).

2.2. Genome Characteristics and E. coli Typing

Assembly of both Ec-1 and Ec-2 strains revealed an approximate genome size of 5.2 Mb with a G+C content of 50.7%. Information about genomes characteristics is summarized in Table S1. The functional classification of both annotated genomes using the KEGG2 database showed a majority of genes linked to metabolism (44%), followed by genetic information processing (28%) and signaling and cellular processes (25%). Phylogenetic analysis of Ec-1 and Ec-2 isolates showed a core genome of 5,203,887 base pair (bp) with six single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) (evolutionary distance of 1.15 SNPs/Mb) and one of them was the R163S mutation in blaKPC-3 (Table S2) designated as blaKPC-49 (accession number MN619655). Ec-1 and Ec-2 isolates were identified as ST131 by the Achtman scheme. Both ST131 isolates belonged to the serotype O25:H4 and were assigned to phylogroup B2. Moreover, both strains carried the fimH30 allele and were identified as subclone H30R1 (clade 1).

2.3. Resistance and Virulence Profile

Ec-1 and Ec-2 isolates contained the same antibiotic resistance genes conferring resistance to β-lactams (blaKPC-like, blaOXA-9, blaTEM-1, blaEC-6), aminoglycosides (aac3-IId, aadA5, aph(3″)-Ib and aph(6)-Id), macrolides (mphA-mrx), sulfonamides (sul1, sul2), tetracycline (tetA), and trimethoprim (dfrA17). Genes encoding blaCTX-M or other carbapenemases were not detected. Ec-2 isolate carried the novel variant blaKPC-49, differing from blaKPC-3 by a single nucleotide substitution (nt 487, C-A) resulting in the arginine-for-serine substitution at amino acid position 163 (R163S). Genes encoding multidrug resistance efflux pumps (acrAB-TolC, H-NS, emr and mdt) and acid resistance systems (gadXW) were also identified in both E. coli isolates. Moreover, fluoroquinolone resistance mutations in quinolone resistance-determining region (QRDR), including gyrA (S83L, D87N), parC (S80I, E84V), and parE (I529L), were found in both Ec-1 and Ec-2 isolates.

An identical virulence factor composition was detected in both ST131-E. coli isolates: aslA, chuA, chuS-Y, entB-F, entS, fdeC, fepA-D, fepG, fes, fimC-I, fyuA, irp1-2, iucA-D, iutA, kpsD, ompA, papB, papX, sat, senB, yagV/ecpE, yagW/ecpD, yagX/ecpC, yagY/ecpB, yagZ/ecpA, ybtA, ybtE, ybtP, ybtQ, ybtS, ybtT, ybtU, ybtX, ykgK/ecpR.

2.4. blaKPC Genetic Environment

KPC-3 and the novel KPC-49 variant were located on an IncFII plasmid also harboring FIA/FIB replicons. In silico pMLST typing confirmed that this IncF-FIA-FIB plasmid belonged to the F1:A2:B20 sequence type. Both blaKPC-3 and blaKPC-49 genes were found as part of the composite transposon Tn4401 (Tn3) designated as “isoform a” variant.

2.5. Resistance Phenotype Conferred by blaKPC-49 Gene

pKPC-3 and pKPC-49 recombinant plasmids were successfully obtained by cloning. Subsequently, pKPC-3 or pKPC-49 were transformed into the isogenic E. coli DH5-α strain. Additionally, with the purpose of investigating the resistance phenotype conferred by KPC-49 enzyme in comparison to KPC-3 in a genetic background more similar to the most common K. pneumoniae clinical strains, pKPC-3 and pKPC-49 plasmids were also transformed into the porin deficient SHV-5-producing K. pneumoniae CSUB10R (ΔompK35; ΔompK36; ΔompK37) strain. Changes in the MIC values of ceftazidime-avibactam and carbapenem antibiotics were non observed between pKPC-3- and pKPC-49 E. coli DH5-α transformants using microdilution and MIC gradient strips (Table 1). Nevertheless, an increased ceftazidime-avibactam MIC (≥3.5-fold) and a reduction of the MIC values for carbapenems, particularly imipenem (≥3-fold), were detected by gradient strips in the pKPC-49-K. pneumoniae-CSUB10R transformant over the corresponding pKPC-3-K. pneumoniae-CSUB10R (Table 1).

3. Discussion

To the best of our knowledge, we report for the first time an ST131-H30R1-E. coli strain producing a new KPC variant, the R163S mutant of blaKPC-3, conferring decreased susceptibility to ceftazidime-avibactam and designated as KPC-49. This ST131-E. coli strain was detected in a blood sample recovered from a patient during the antibiotic treatment with ceftazidime-avibactam (day 10). Typing characterization by WGS identified this ST131 strain as the H30R1 subclone, serotype O25:H4. The ST131-H30R1-E. coli subclone has been recently described in Europe as an emerging MDR pathogen involved in rectal colonization and associated with CTX-M-27 production (C1-M27 subclade) [6].

Association of ST131 strains with the production of KPC enzymes has been scarcely described and the few reports are in countries with a high endemicity level of KPC-producing K. pneumoniae [20,21]. For instance, a high incidence of the high-risk clone ST307-KPC-3-producing K. pneumoniae has been recently reported in both colonized and infected patients in our institution during the last two years (unpublished data). The persistence of certain K. pneumoniae clones, such as ST307, in the patient microbiome plays a crucial role in the cross-species transfer of carbapenemase genes [22,23]. Interestingly, a KPC-producing-K. pneumoniae isolate was also detected in a rectal sample from our patient during the admission. So that, we cannot rule out that the presence of this isolate in the patient microbiome could have facilitated the horizontal acquisition of blaKPC-3 gene by the ST131-E. coli.

Overall, the dissemination of blaKPC among different Enterobacterales species has been mainly related to the transposable element Tn4401a which is often carried on different conjugative plasmids [24]. In fact, cross-species transfer of IncF blaKPC-3-encoding plasmids from K. pneumoniae to E. coli have been previously described in infected patients [25]. On the other hand, IncFII plasmids with FIA/FIB replicons have also been detected among ST131-E. coli isolates, mostly linked to the blaESBLs genes dissemination. IncF (F1:A2:B20) plasmids have been usually associated with the H30R1 clade and IncF (F2:A1:B-) plasmids with the H30Rx clade [26,27]. Coincidentally, we found the ST131-H30R1 subclone harboring an IncF (F2:A1:B20) plasmid but encoding blaKPC-3 and the novel blaKPC-49 variant, not an ESBL-encoding gene. Furthermore, in contrast with previous studies [28], we found in both ST131-E. coli isolates a complete Tn4401a transposon, identical to that described in K. pneumoniae strains during the last decade. In fact, Tn4401a has been previously identified in our hospital as the genetic platform involved in the mobilization and diffusion of the blaKPC-3 gene in K. pneumoniae [24]. On the other hand, although blaCTX-M genes has been largely found inserted in both IncF-type plasmids and chromosomal locations in ST131-E. coli isolates [28], CTX-M-encoding genes were not detected in our isolates.

Coinciding with the reported literature, a high number of virulence and resistance genes was identified in both KPC-3- and KPC-49-ST131-H30R1-E. coli isolates [1,5]. The ST131-E. coli isolate recovered at admission showed a multidrug resistance profile, leaving few therapeutics options, as ceftazidime-avibactam, to treat the blood infection.

Although the in vivo clinical efficacy of ceftazidime-avibactam has been widely demonstrated [12,13], several studies have recently reported in K. pneumoniae epidemic clones the emergence of new ceftazidime-avibactam resistant KPC enzymes derived from point mutations in blaKPC-2 and blaKPC-3 genes, frequently after the antibiotic exposure [16,17,18]. In all cases, in vitro meropenem susceptibility was fully or partially restored due to these blaKPC mutations resulting in KPC-producing K. pneumoniae isolates with a phenotype resembling that of ESBL producers [16,17,18]. According to these data, the impact of ceftazidime-avibactam resistance could be minimized due to the lower carbapenem MICs. However, some studies have shown that after the discontinuation of ceftazidime-avibactam treatment, carbapenem resistant phenotype can be restored in K. pneumoniae isolates that still display ceftazidime-avibactam resistance [18]. In our study, a higher susceptibility to meropenem, imipenem, and piperacillin-tazobactam was observed in the KPC-49-ST131 strain coinciding with the increased ceftazidime-avibactam MIC. In concordance with previous reports, this resistance phenotype resembled that of an ESBL producer [16,17,18]. Importantly, our region is considered an endemic area of ESBL-producing E. coli isolates [29] and the emergence of the ST131-E. coli producing KPC carbapenemases but with an ESBL resistance profile could lead to under reporting of infections by KPC producers with potential carbapenemase activity.

According to our results, this resistance phenotype could be consequence of the R163S mutation in blaKPC-3. It is noteworthy that the blaKPC-49 was more clearly validated as a ceftazidime-avibactam resistance determinant in the porin-deficient strain K. pneumoniae CSUB10R. Previous studies have also demonstrated that mutated or non-functional OmpK35 and Ompk36 porins slightly contribute to increase ceftazidime-avibactam MICs in KPC-3-producing K. pneumoniae isolates [30,31]. It should also be noted that the K. pneumoniae CSUB10R strain shares a similar genetic background to the MDR-K. pneumoniae clinical strains that usually circulate in the hospital setting causing severe and difficult-to-treat infections. We believe that the potential contribution of the ST131-E. coli clone in the dissemination of novel blaKPC genes conferring ceftazidime-avibactam resistance, such as blaKPC-49, in epidemic K. pneumoniae clinical strains should be a cause of great concern for public health.

4. Material and Methods

4.1. Bacterial Isolates, Susceptibility Testing, and Patient’s Data

Bacterial identification was carried out using MALDI-TOF-MS (Bruker-Daltonics, Bremen, Germany). Minimum inhibitory concentrations (MICs) were determined by standard broth microdilution. Ceftazidime-avibactam susceptibility was additionally tested using gradient strips (Liofilchem, Roseto degli Abruzzi, Italy). We defined susceptible isolates as those categorized as S (susceptible, standard dose regimen) and I (susceptible, increased exposure) according to EUCAST-2019 criteria (http://www.eucast.org/clinical_breakpoints/). Clinical chart review was performed after local ethical committee approval (Ref. 293/19).

4.2. Resistance Genes Characterization

Carbapenemase genes were detected initially by the eazyplex®-Superbug-CRE system (Amplex-Biosystems GmbH, Giessen, Germany) and later confirmed by PCR and Sanger sequencing [32].

4.3. DNA Extraction, Whole Genome Sequencing, and Bioinformatics Analysis

Total DNA extraction from 2 mL exponential growth cultures was performed by the Chemagic DNA Bacterial External Lysis Kit (PerkinElmer Inc., Waltham, MA, USA). Whole genome sequencing was carried out by the Illumina NovaSeq 6000 platform (OGC, Oxford, UK) with 2 × 150 pb paired-end reads. Quality control and filtering of sequences were performed using FastQC v.0.11.8 (https://www.bioinformatics.babraham.ac.uk/projects/fastqc/) and Prinseq-lite-0.20.3 (http://prinseq.sourceforge.net/) tools, respectively. Preprocessing short-reads were assembled de novo using SPAdes v3.11.1 [33] and assembly evaluation was performed by QUAST v5.0.2 (http://quast.bioinf.spbau.ru/). The draft genomes were annotated by Prokka v.1.13.3 [34] and the functional categorization of predicted protein sequences were also classified using the KEGG Automatic Annotation Server and the KEGG2 database (http://www.genome.jp/kegg/kaa). Antimicrobial resistance and virulence genes were identified using Abricate v0.8.11 with the ResFinder, ARG-ANNOT, CARD and VFDB databases (threshold, 98% identity; 90% coverage). MLST v2.16.1 (https://github.com/tseemann/mlst) and the Achtman MLST scheme (http://mlst.warwick.ac.uk/mlst/dbs/Ecoli) were used in the in silico MLST assignment. Phylogroups, serotypes and fimH types were determined using ClermonTyping [35], SerotypeFinder and FimTyper (https://cge.cbs.dtu.dk/services/) tools, respectively. H30Rx sublineage was identified based on the G723A point mutation in ybbW using Blastn (http://blast.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/Blast.cgi) [36]. Chromosomal point mutations (gyrA, parC and parE genes) were identified using PointFinder software (https://cge.cbs.dtu.dk/services/). Variant calling was performed by Snippy v4.3.2 program. BWA-MEM v0.7.17 and Samtools v1.9 softwares were also used to confirm the presence of mutations between isolates. The genetic environment and the mobile genetic elements implicated in the dissemination of the blaKPC gene were characterized using PlasmidFinder and Plasmidspades v3.11.1 [37].

4.4. Validation of blaKPC-49 Variant

blaKPC-3 and blaKPC-49 genes were amplified by PCR using primers KPC-F (5′-AGGAATATCGTTGATGTCACT-3′) and KPC-R (5′-CTTACTGCCCGTTGACGCC-3′) and cloned into the pCR-Blunt II-TOPO vector following the manufacturer’s instructions (Zero Blunt TOPO PCR cloning kit; Invitrogen, Cergy-Pontoise, France). The recombinant plasmids pKPC-3 and pKPC-49 were transformed by heat shock into competent E. coli cells (NEB 5-alpha competent E. coli; New England BioLabs Inc., Ipswich, MA, USA) and then selected on Luria broth agar medium supplemented with ampicillin (30 mg/L), kanamycin (50 mg/L) and IPTG (isopropyl-β-D-thiogalactopyranoside)-Xgal (5-bromo-4-chloro-3-indolyl-β-D-galactopyranoside) (80 mg/L). Both pKPC-3 and pKPC-49 plasmids were also transferred by electroporation into the porin-deficient SHV-5-producing K. pneumoniae CSUB10R strain (ΔompK35; ΔompK36; ΔompK37) [38] and then selected in Luria broth agar medium supplemented with imipenem (4 mg/L). Successful transfer of blaKPC genes was confirmed by PCR and Sanger sequencing. MIC values in KPC-3 and KPC-49 transformants were also measured by broth microdilution. Additionally, most of the β-lactam antibiotics including ceftazidime-avibactam were tested in triplicate using MIC test strips.

4.5. Sequence Data

The blaKPC-49 gene and the complete genomes of both ST131-H30R1-E. coli isolates were deposited at DDBJ/ENA/GenBank under accession numbers MN619655, WIRF00000000 and WIRG00000000, respectively.

5. Conclusions

In the present work we report the in vivo emergence of a novel KPC variant (KPC-49) conferring a phenotype resembling that of ESBL producers in the ST131-E. coli high-risk clone during the treatment with ceftazidime-avibactam. The global expansion of the ST131-H30-E. coli high-risk clone in both community and hospital settings together with the successful acquisition of IncF-type plasmids harboring blaKPC genes that function as ESBL genes but also conferring resistance to new β-lactam and β-lactamase inhibitor combinations such as ceftazidime-avibactam, poses a new challenge to the patient management and the containment programs design to avoid the spread of MDR pathogens.

Supplementary Materials

The following are available online at https://www.mdpi.com/2076-0817/10/1/67/s1, Table S1: Genomic characteristics of KPC-producing E. coli isolates; Table S2: SNPs detected in the core genome of both KPC-producing E. coli isolates.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, M.H.-G., P.R.-G. and R.C.; Data curation, M.H.-G.; Formal analysis, M.H.-G.; Funding acquisition, P.R.-G. and R.C.; Investigation, M.H.-G., J.S.-L., L.M.-G., F.B.-A. and M.I.M.; Methodology, M.H.-G., J.S.-L., L.M.-G. and F.B.-A.; Supervision, M.I.M., P.R.-G. and R.C.; Writing—original draft, M.H.-G.; Writing—review & editing, M.I.M., P.R.-G. and R.C. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

M.H.-G. was supported with a contract from FIBIO (Fundación para la Investigación Biosanitaria del Instituto Ramón y Cajal de Investigaciones Sanitarias, IRYCIS, Madrid, Spain). We acknowledge financial support from Plan Nacional de I+D+I 2013–2016 and Instituto de Salud CarlosIII, Subdirección General de Redes y Centros de Investigación Cooperativa, Ministerio de Economía, Industria y Competitividad, Spanish Network for Research in Infectious Diseases (REIPI RD16/0016/0011) co-financed by European Development Regional Fund “A way to achieve Europe” (ERDF), Operative program Intelligent Growth 2014–2020. We also thank Mrs. Mary Harper for English correction of the manuscript.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted according to the guidelines of the Declaration of Helsinki, and approved by the Ramón y Cajal University Hospital Ethics Committee (Reference 293/19).

Informed Consent Statement

Patient consent was waived because it was not required by Ethics Committee since patient data was anonymized.

Ethics Committee Approval

This study was approved by the Ramón y Cajal University Hospital Ethics Committee (Reference 293/19).

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Footnotes

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Johnson J.R., Johnston B., Clabots C., Kuskowski M.A., Castanheira M. Escherichia coli Sequence Type ST131 as the Major Cause of Serious Multidrug-Resistant, E. coli Infections in the United States. Clin. Infect. Dis. 2010;51:286–294. doi: 10.1086/653932. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Johnson J.R., Menard M., Johnston B., Kuskowski M.A., Nichol K., Zhanel G.G. Epidemic clonal groups of Escherichia coli as a cause of antimicrobial-resistant urinary tract infections in Canada, 2002 to 2004. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 2009;53:2733–2739. doi: 10.1128/AAC.00297-09. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Nicolas-Chanoine M.H., Bertrand X., Madec J.Y. Escherichia coli st131, an intriguing clonal group. Clin. Microbiol. Rev. 2014;27:543–574. doi: 10.1128/CMR.00125-13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Johnson J.R., Tchesnokova V., Johnston B., Clabots C., Roberts P.L., Billig M., Riddell K., Rogers P., Qin X., Butler-Wu S., et al. Abrupt emergence of a single dominant multidrug-resistant strain of Escherichia coli. J. Infect. Dis. 2013;207:919–928. doi: 10.1093/infdis/jis933. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Lance B.P., Johnson J.R., Aziz M., Clabots C., Johnston B., Tchesnokova V., Nordstrom L., Billig M., Chattopadhyay S., Stegger M., et al. The Epidemic of extended-spectrum-beta-lactamase-producing Escherichia coli ST131 is driven by a single highly pathogenic subclone, H30-Rx. Am. Soc. Microbiol. 2013;4:1–10. doi: 10.1128/mBio.00377-13.Editor. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Merino I., Hernández-García M., Turrientes M.C., Pérez-Viso B., López-Fresneña N., Díaz Agero C., Maechler F., Fankhauser-Rodriguez C., Kola A., Schrenzel J., et al. Emergence of ESBL-E. coli-ST131-C1-M27 clade colonizing patients in Europe. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 2018;73:2973–2980. doi: 10.1093/jac/dky296. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ortega A., Sáez D., Bautista V., Fernández-Romero B., Lara N., Aracil B., Pérez-Vázquez M., Campos J., Oteo J. Carbapenemase-producing Escherichia coli is becoming more prevalent in Spain mainly because of the polyclonal dissemination of OXA-48. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 2016;71:2131–2138. doi: 10.1093/jac/dkw148. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Naas T., Cuzon G., Villegas M.V., Lartigue M.F., Quinn J.P., Nordmann P. Genetic structures at the origin of acquisition of the β-lactamase blaKPC gene. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 2008;52:1257–1263. doi: 10.1128/AAC.01451-07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Muñoz-Price S., Poirel L., Bonomo R., Schwaber M., Daikos G., Cormican M., Cornaglia G., Garau J. Clinical epidemiology of the global expansion of Klebsiella pneumoniae carbapenemases. Lancet Infect. Dis. 2013;13:785–796. doi: 10.1016/S1473-3099(13)70190-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Suay-García B., Pérez-Gracia M.T. Present and future of carbapenem-resistant Enterobacteriaceae (CRE) infections. Antibiotics. 2019;8:122. doi: 10.3390/antibiotics8030122. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Carmeli Y., Armstrong J., Laud P.J., Newell P., Stone G., Wardman A., Gasink L.B. Ceftazidime-avibactam or best available therapy in patients with ceftazidime-resistant Enterobacteriaceae and Pseudomonas aeruginosa complicated urinary tract infections or complicated intra-abdominal infections (REPRISE): A randomised, pathogen-directed. Lancet Infect. Dis. 2016;16:661–673. doi: 10.1016/S1473-3099(16)30004-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Wu G., Abraham T., Lee S. Ceftazidime-avibactam for treatment of carbapenem-resistant enterobacteriaceae bacteremia. Clin. Infect. Dis. 2016;63:1147–1148. doi: 10.1093/cid/ciw491. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Gugliandolo A., Caio C., Mezzatesta M.L., Rifici C., Bramanti P., Stefani S., Mazzon E. Successful ceftazidime-avibactam treatment of MDR-KPC-positive Klebsiella pneumoniae infection in a patient with traumatic brain injury. Medicine. 2017;96:1–6. doi: 10.1097/MD.0000000000007664. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Van Duin D., Lok J.J., Earley M., Cober E., Richter S.S., Perez F., Salata R.A., Kalayjian R.C., Watkins R.R., Doi Y., et al. Colistin versus veftazidime-avibactam in the treatment of infections due to carbapenem-resistant Enterobacteriaceae. Clin. Infect. Dis. 2018;66:163–171. doi: 10.1093/cid/cix783. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Johnston B.D., Thuras P., Porter S.B., Anacker M., VonBank B., Vagnone P.S., Witwer M., Castanheira M., Johnson J.R. Activity of cefiderocol, ceftazidime-avibactam, and eravacycline against carbapenem-resistant Escherichia coli isolates from the United States and international sites in relation to clonal background, resistance genes, coresistance, and region. Antimicrob. Agent Chemother. 2020;64:1–10. doi: 10.1128/AAC.00797-20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Shields R.K., Chen L., Cheng S., Chavda K.D., Press E.G. Emergence of ceftazidime-avibactam mutations during treatment of carbapenem-resistant Klebsiella pneumoniae Infections. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 2016;61:1–11. doi: 10.1128/AAC.02097-16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Haidar G., Clancy J.C., Shields R.K., Hao B.C., Cheng S., Nguyen M.H. Mutations in blaKPC-3 That confer ceftazidime-avibactam resistance encode novel KPC-3 variants that function as extended-spectrum β-lactamases. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 2017;61:1–6. doi: 10.1128/AAC.02534-16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Giddins M.J., Macesic N., Medini K.A., Stump S., Khan S., McConville T.H., Mehta M., Gomez-Simmonds A., Uhlemann A.-C. Successive emergence of ceftazidime-avibactam resistance through distinct genomic adaptations in blaKPC-2-harboring Klebsiella pneumoniae sequence type 307 Isolates. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 2018;62:1–8. doi: 10.1128/AAC.02101-17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Plan de Prevención y control frente a la infección por EPC en la Comunidad de Madrid. [(accessed on 13 January 2021)]; Versión 1-September 2013. Available online: https://www.comunidad.madrid/servicios/salud/prevencion-control-infecciones-epc.

- 20.Ripabelli G., Sammarco M.L., Scutellà M., Felice V., Tamburro M. Carbapenem-resistant KPC- and TEM-producing Escherichia coli ST131 isolated from a hospitalized patient with urinary tract infection: First isolation in molise region, central Italy, July 2018. Microb. Drug Resist. 2019;26 doi: 10.1089/mdr.2019.0085. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Piazza A., Caltagirone M., Bitar I., Nucleo E., Spalla M., Fogato E., D’Angelo R., Pagani L.R.M. Emergence of Escherichia coli sequence type 131 (ST131) and ST3948 with KPC-2, KPC-3 and KPC-8 carbapenemases from a long-term care and rehabilitation Facility (LTCRF) in Northern Italy. Adv. Exp. Med. Biol. 2015 doi: 10.1007/5584_2015_5017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Hernández-García M., Pérez-Viso B., Navarro-San Francisco C., Baquero F., Morosini M.I., Ruiz-Garbajosa P., Cantón R. Intestinal co-colonization with different carbapenemase-producing Enterobacterales isolates is not a rare event in an OXA-48 endemic area. EClinicalMedicine. 2019;15:72–79. doi: 10.1016/j.eclinm.2019.09.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Baquero F., Coque T.M., Martínez J.L., Aracil-Gisbert S., Lanza V.F. Gene transmission in the one health microbiosphere and the channels of antimicrobial resistance. Front. Microbiol. 2019;10:1–14. doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2019.02892. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Curiao T., Morosini M.I., Ruiz-Garbajosa P., Robustillo A., Baquero F., Coque T.M., Cantón R. Emergence of blaKPC-3-Tn4401a associated with a pKPN3/4-like plasmid within ST384 and ST388 Klebsiella pneumoniae clones in Spain. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 2010;65:1608–1614. doi: 10.1093/jac/dkq174. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Gona F., Barbera F., Pasquariello A.C., Grossi P., Gridelli B., Mezzatesta M.L., Caio C., Stefani S., Conaldi P.G. In Vivo multiclonal transfer of blaKPC-3 from Klebsiella pneumoniae to Escherichia coli in surgery patients. Clin. Microbiol. Infect. 2014;20:633–635. doi: 10.1111/1469-0691.12577. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kanamori H., Parobek C.M., Juliano J.J., Johnson J.R., Johnston B.D., Johnson T.J., Weber D.J., Rutala W.A., Anderson D.J. Genomic analysis of multidrug-resistant Escherichia coli from North Carolina community hospitals: Ongoing. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 2017;61:1–13. doi: 10.1128/AAC.00912-17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Johnson T.J., Danzeisen J.L., Youmans B., Case K., Llop K., Munoz-aguayo J., Flores-figueroa C., Aziz M., Stoesser N., Sokurenko E., et al. Separate F-type plasmids have shaped the evolution of the H 30 subclone of. mSphere. 2016;1:1–15. doi: 10.1128/mSphere.00121-16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Stoesser N., Sheppard A.E., Pankhurst L., de Maio N., Moore C.E., Sebra R., Turner P., Anson L.W., Kasarskis A., Batty E.M., et al. Evolutionary history of the global emergence of the Escherichia coli epidemic clone ST131. MBio. 2016;7:1–15. doi: 10.1128/mBio.02162-15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Díaz M.A., Hernández-Bello J.R., Rodríguez-Baño J., Martínez-Martínez L., Calvo J., Blanco J., Pascual A. Diversity of Escherichia coli strains producing extended-spectrum β-lactamases in Spain: Second nationwide study. J. Clin. Microbiol. 2010;48:2840–2845. doi: 10.1128/JCM.02147-09. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Humphries R.M., Hemarajata P. Resistance to ceftazidime-Avibactam in Klebsiella pneumoniae due to porin mutations & the increased expression of KPC-3. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 2017;61:10–11. doi: 10.1128/AAC.00537-17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Nelson K., Hemarajata P., Sun D., Rubio-Aparicio D., Tsivkovski R., Yang S., Sebra R., Kasarskis A., Nguyen H., Hanson B.M., et al. Resistance to Ceftazidime–Avibactam is due to transposition of KPC in a Porin–Deficient strain of Klebsiella pneumoniae. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 2017;61:e00989-17. doi: 10.1128/AAC.00989-17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.García-Fernández S., Morosini M.I., Marco F., Gijón D., Vergara A., Vila J., Ruiz-Garbajosa P., Cantón R. Evaluation of the eazyplex® SuperBug CRE system for rapid detection of carbapenemases and ESBLs in clinical Enterobacteriaceae isolates recovered at two Spanish hospitals. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 2014;70:1047–1050. doi: 10.1093/jac/dku476. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Bankevich A., Nurk S., Antipov D., Gurevich A.A., Dvorkin M., Kulikov A.S., Lesin V.M., Nikolenko S.I., Pham S.O.N., Prjibelski A.D., et al. SPAdes: A new genome assembly algorithm and its applications to single-cell sequencing. J. Comput. Biol. 2012;19:455–477. doi: 10.1089/cmb.2012.0021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Seemann T. Prokka: Rapid prokaryotic genome annotation. Bioinformatics. 2014;30:2068–2069. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btu153. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Beghain J., Bridier-Nahmias A., Nagard H.L., Denamur E., Clermont O. ClermonTyping: An easy-to-use and accurate in silico method for Escherichia genus strain phylotyping. Microb. Genom. 2018;4:1–8. doi: 10.1099/mgen.0.000192. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Banerjee R., Robicsek A., Kuskowski M.A., Porter S., Johnston B.D., Sokurenko E., Tchesnokova V., Price L.B., Johnson J.R. Molecular epidemiology of Escherichia coli sequence type 131 and its H30 and H30-Rx subclones among extended-spectrum-β-lactamase-positive and -negative E. coli clinical isolates from the Chicago region, 2007 to 2010. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 2013;57:6385–6388. doi: 10.1128/AAC.01604-13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Antipov D., Hartwick N., Shen M., Raiko M., Lapidus A., Pevzner P.A. Plasmidspades: Assembling plasmids from whole genome sequencing data. Bioinformatics. 2016;32:3380–3387. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btw493. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Ardanuy C., Liñares J., Domínguez M.A., Hernández-Allés S., Benedí V.J., Martínez-Martínez L. Outer membrane profiles of clonally related Klebsiella pneumoniae isolates from clinical samples and activities of cephalosporins and carbapenems. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 1998;42:1636–1640. doi: 10.1128/AAC.42.7.1636. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.