Historically, infectious disease outbreaks have exposed social inequalities. It is clear that coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) is doing the same and, even though historians shy away from looking into the crystal ball, it seems that the global experience with the virus will be shaped by inequities. Like the influenza outbreak in 1918–1920, COVID-19 is not a democratic disease.

History shows that lived experience during an epidemic is influenced by factors such as trust in and access to health care, the availability of financial and social supports that are equitable and based in social justice, and the fulfillment of basic human needs, such as clean, running water and safe workplaces.

Several historians have documented social differentials during the 1918 influenza outbreak in Canada. In urban centres, death rates per population varied considerably by socioeconomic status, ethnicity and race. Poorer neighbourhoods, including those with families that had recently immigrated to Canada, had higher mortality rates in cities like Winnipeg and Hamilton.1,2 Deaths among Indigenous people were higher than among non-Indigenous people: 6.2 out of every 1000 non-Indigenous Canadians died of influenza, whereas known death rates among Indigenous people living on reserves ranged from 10.3 per 1000 population in Prince Edward Island to 61 per 1000 in Alberta.3

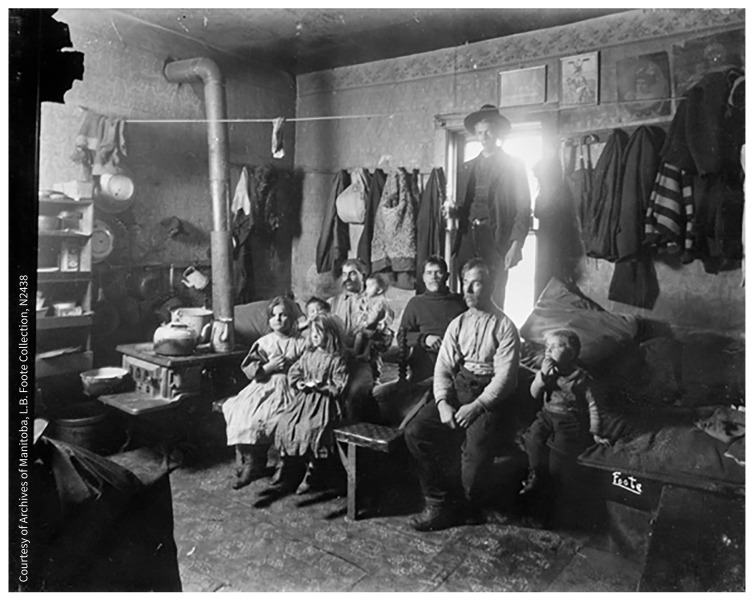

The numbers tell only part of the story, however. The flu pandemic was also qualitatively different for those most deeply affected by it, and it altered their life courses in distinctive ways. The wealthy were not immune during the influenza pandemic, but they had capacity to combat the disease that the poor did not. Influenza spread quickly through households in densely populated urban areas, where families had limited access to hot, running water; houses were cheaply constructed and poorly ventilated; and where the physical isolation of the infected was virtually impossible. The poor state of housing and the lack of key sanitary infrastructure in working-class districts was not unknown, but governments had done nothing to ameliorate it. Had they done so, influenza may not have spread as rapidly as it did, infecting entire families.

Unidentified family (1910).

Image courtesy of Courtesy of Archives of Manitoba, L.B. Foote Collection, N2438

In a pre–welfare state era, Canadians faced a dilemma, caught between continuing to do paid work and going without food or paying the rent. Individual quarantine measures were introduced to slow the spread of the disease, but these were not accompanied by income supports. Health officials were, rightly, afraid that people would not report their illnesses so that they could continue on the job. Even now we don’t really know the extent to which people worked when ill. We do know that waged workers who missed work because of illness had no legal right to sick pay — still the case in Canada today — and there was no government employment insurance. Employees like the theatre workers in Winnipeg, who lost their wages for more than six weeks because of public closures of places of leisure, were denied any income relief from the government authorities who had closed their workplaces. Appealing to City Hall for support, their wives and union representatives advocating on their behalf were told that everyone in society had to do their bit. Attitudes like this contributed to labour unrest, culminating in the historic strike waves of early 1919.

Most Canadians in 1918–1919 would have faced barriers to accessing preventive or curative health care during the pandemic. The public health system was still small and underdeveloped, especially in rural areas. Some rural municipalities (despite their key role in implementing public health measures at the time) did not have health officers or permanent health boards. Most provinces had no departments of health. Ontario’s, for example, was created in 1924 and British Columbia’s in 1946. The federal government’s public health department did not exist until 1919, created after the pandemic. Preventive infrastructure was minimal, and there was unequal access to medical treatment.

Physicians worked in private practice across the country. Many people could not afford treatment by a physician or a visiting nurse. Hospital care was available to some extent, but this was patchwork. There was no universal public insurance for admission to hospital; the first province to introduce this was Saskatchewan, in 1945. Religious hospitals and “general” hospitals partly funded by governments had been expanding in the early 20th century, but their relationship with the larger community was problematic. The hospital segregation of racial minorities and Indigenous people was frequent. Asian Canadians at the Vancouver General Hospital, for example, were treated in a segregated basement ward.4 Similar racial segregation existed in those few general hospitals that would treat Indigenous people; overall, access to health care for Indigenous people was limited and inequitable. As Maureen Lux argues in her recent study, Separate Beds, “The Indian annexes, Indian wings, and basement wards, demanded by community prejudice and inadequately funded by the state, actively shaped inequality and constructed an image of Aboriginal people as less worthy of care.”5

Poor white patients were housed in wards much less pleasant or private than those for middle-class patients who could afford to pay. Eligibility for hospital coverage in publicly funded hospitals was often means tested through intrusive personal financial questions. This was a demoralizing process for patients and, if hospital administrators considered families able to pay, care was allegedly often withheld.

All of these factors contributed to mistrust of the health care system during the 1918–1920 flu pandemic, which may have deterred influenza sufferers from seeking care. Many influenza victims in Canada suffered, survived or died the way they had through previous outbreaks of infectious diseases: in their homes, with the help of family and neighbours, if they were fortunate. Mutual aid, both formal and informal, sustained communities.

The 1918–1920 influenza pandemic was especially challenging because of the demographic profile of its victims, who were mostly younger adults between the ages of 20 and 40 years. In some locations, more men died than women. The economic and emotional consequences for children and families were severe. If a male breadwinner died, families experienced downward economic mobility from which they often could not recover. This was exacerbated by gender inequality in the labour market; women had few employment options and faced unequal pay. In some cases, female single parents whose husbands died from flu could qualify for mothers’ allowances, but only Manitoba and Saskatchewan had enacted these programs by 1918; Alberta’s was introduced in 1919.6 Benefits were means tested and miserly and were accompanied by ongoing scrutiny and questioning of women’s behaviour, parenting skills and housekeeping. In Manitoba, benefits were withdrawn when a child turned 14 and, as a result, most had to leave school to enter the workforce. Thus did influenza limit the life chances of a generation of children from poorer backgrounds.

If mothers died of influenza, fathers struggled to find care for young children. This was one factor that drove an increase in institutional care in orphanages in the post-pandemic period. An understudied aspect of the flu pandemic’s social impact is the institutionalization of children who had lost one or both parents to influenza. In Winnipeg, the Protestant Winnipeg Children’s Home housed the children of flu victims, as did the Jewish Orphanage, which expanded to accommodate the increased need from across Western Canada.7 Orphanage care, still common at the time, was used by some parents to ensure the security and survival of their children. However, it posed a threat to family connection during a time of widespread grief and loss.

Life in Canada after the pandemic was unsettled, and its normal social structures unstable. In 1919 there was labour unrest across the country, most famously the Winnipeg General Strike, which began in May 1919 and shut down the city for almost six weeks. At the heart of these struggles was the need for a “living wage.” Labour activism, however, was harshly suppressed by governments, with the use of force and imprisonment. Social change occurred only slowly. Calls for health care reform, when they did fully coalesce in the labour and farmer movements of the 1930s, drew from international models of socialized health care that had developed after the pandemic, including the “red medicine” of the Soviet Union.8 The birth of Canadian medicare can be traced to these movements for greater health equity.

Footnotes

This article has been peer reviewed.

Competing interests: None declared.

CMAJ Podcasts: author interview at https://soundcloud.com/cmajpodcasts/201074-medsoc

References

- 1.Jones EW. Influenza 1918: death, disease and struggle in Winnipeg. Toronto: University of Toronto Press; 2007: 59–63. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Herring DA, Korol E. The north south divide: social inequality and mortality from the 1918 influenza pandemic in Hamilton, Ontario. In: Fahrni M, Jones EW. editors. Epidemic encounters: influenza, society, and culture in Canada, 1918–1920. Toronto: University of Toronto Press; 2012:97–112. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Humphries M. The last plague: Spanish influenza and the politics of public health in Canada. Toronto: University of Toronto Press; 2013:128. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Gagan D, Gagan R. “Evil reports” for “ignorant minds”? Patient experience and public confidence in the emerging modern hospital: Vancouver General Hospital, 1912”. Can Bull Med Hist 2001;18:349–67. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Lux MK. Separate beds: a history of Indian hospitals in Canada, 1920s–1980s. Toronto: University of Toronto Press; 2016: 21. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Gavigan S, Chunn D. From Mothers’ Allowance to mothers need not apply: Canadian welfare law as legal and neo-liberal reforms. Osgoode Hall Law J 2007;45: 741 n 24. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Graham S. Building Canadian Jewish citizens out of the abandoned children of Western Canada: the Winnipeg Jewish Orphanage, 1917–1948 [dissertation]. Winnipeg: University of Manitoba; 2020:87. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Jones EW. Radical medicine: the international origins of socialized health care in Canada. Winnipeg: ARP Books; 2019. [Google Scholar]