Abstract

BACKGROUND:

Pandemic severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2) is associated with high intensive care unit (ICU) mortality. We aimed to describe the clinical characteristics and outcomes of critically ill patients with coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) in a Canadian setting.

METHODS:

We conducted a retrospective case series of critically ill patients with laboratory-confirmed SARS-CoV-2 infection consecutively admitted to 1 of 6 ICUs in Metro Vancouver, British Columbia, Canada, between Feb. 21 and Apr. 14, 2020. Demographic, management and outcome data were collected by review of patient charts and electronic medical records.

RESULTS:

Between Feb. 21 and Apr. 14, 2020, 117 patients were admitted to the ICU with a confirmed diagnosis of COVID-19. The median age was 69 (interquartile range [IQR] 60–75) years, and 38 (32.5%) were female. At least 1 comorbidity was present in 86 (73.5%) patients. Invasive mechanical ventilation was required in 74 (63.2%) patients. The duration of mechanical ventilation was 13.5 (IQR 8–22) days overall and 11 (IQR 6–16) days for patients successfully discharged from the ICU. Tocilizumab was administered to 4 patients and hydroxychloroquine to 1 patient. As of May 5, 2020, a total of 18 (15.4%) patients had died, 12 (10.3%) remained in the ICU, 16 (13.7%) were discharged from the ICU but remained in hospital, and 71 (60.7%) were discharged home.

INTERPRETATION:

In our setting, mortality in critically ill patients with COVID-19 admitted to the ICU was lower than in previously published studies. These data suggest that the prognosis associated with critical illness due to COVID-19 may not be as poor as previously reported.

Severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2) causes coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19), now characterized as a pandemic by the World Health Organization. 1 Infection rates and deaths worldwide increased exponentially. About 35 000 confirmed cases and more than 1600 deaths were reported in Canada as of Apr. 21, 2020.2 In British Columbia, as of May 20, 2020, there were 2467 confirmed cases and 149 deaths.3 However, the number of new cases has been decreasing since the beginning of April 2020. More than 85% of the cases of COVID-19 in BC have been located in the Metro Vancouver area.3

Initial studies from China4 and Italy5 showed mortality ranging from 26% to 62% in critically ill patients with COVID-19. Studies from Seattle6 and New York7 reported overall mortality ranging from 23% to 50%. In these case series, between 13% and 71% of patients remained in the intensive care units (ICUs) at the time of publication, so actual mortality may be greater than reported. Canadian data describing critically ill patients with COVID-19 are lacking, and better characterization is crucial to direct critical care resource allocation and to understand the disease in our local context. The aim of our multicentre case series was to describe the demographic characteristics, management patterns and outcomes among critically ill patients with COVID-19 in Metro Vancouver.

Methods

We conducted a case series of all patients with COVID-19 admitted to an ICU in the Metro Vancouver area from Feb. 21 to Apr. 14, 2020, with outcomes followed until May 5, 2020. This area serves about 3 million residents of BC (population 4.9 million). The hospitals included were Vancouver General Hospital (46 ICU beds, quaternary hospital), Surrey Memorial Hospital (46 ICU beds, tertiary hospital), Lions Gate Hospital (11 ICU beds, community hospital), St. Paul’s Hospital (15 ICU beds, tertiary hospital), Royal Columbian Hospital (30 ICU beds, tertiary hospital) and Richmond Hospital (8 ICU beds, community hospital). All included ICUs are staffed by fellowship-trained intensive care physicians, operate on a nurse-to-patient ratio of about 1:1.2, and are affiliated with the University of British Columbia. They are all mixed units caring for both medical and surgical patients. In preparation for the pandemic, these hospitals were designated as COVID-19 centres, and, as such, critically ill patients with COVID-19 in their catchment areas were transferred to these sites. Admission into the ICUs occurred at the discretion of the attending critical care physician, but general criteria included all patients with suspected or confirmed SARS-CoV-2 infection who were requiring rapidly increasing oxygen supplementation, oxygen via high-flow nasal cannula, noninvasive positive pressure ventilation, mechanical ventilation or vasopressors. All consecutive patients with laboratory-confirmed SARS-CoV-2 infection who were admitted to one of the participating ICUs during the study period were enrolled.

Laboratory confirmation for SARS-CoV-2 was defined as a positive result on real-time reverse transcription polymerase chain reaction assay of nasal, pharyngeal or lower respiratory tract samples.

Data collection

Data were obtained from patient charts and the electronic medical record from each institution using a combination of professional clinical reviewers, 2 attending intensivists (A.R.M. and A.W.) and a clinical research assistant (N.A.F.). Demographic data, patient histories and examinations, laboratory data and clinical outcomes were collected throughout each patient’s hospital admission. Severity of illness was characterized by the APACHE II (Acute Physiology and Chronic Health Evaluation II) score using data from the first 24 hours of ICU admission.8 Additionally, Sequential Organ Failure Assessment (SOFA)9 on the initial day of ICU admission was used to further describe illness acuity. Depending on the variable, laboratory results were either presented at baseline value or at their peak value within the first 3 days of ICU stay. Mechanical ventilation parameters were recorded about 24 hours after the initiation of mechanical ventilation to ensure these parameters stabilized after intubation. Therapies received during the ICU stay were recorded, including supportive measures and pharmacologic agents. All investigations and therapies were performed at the discretion of the treating physicians. Daily hospital admission and ICU prevalence data were obtained from the Vancouver Coastal Health and Fraser Health authorities. Available ICU capacity data were obtained as part of the COVID-19 phase 1 critical care requirements planning.

Statistical analysis

Descriptive statistics were used to summarize baseline demographic characteristics, clinical characteristics, laboratory results at admission and, for the first 3 days in ICU, frequency of ICU interventions and therapies, ICU prevalence and clinical outcomes. Continuous variables were presented as mean and standard deviation (SD) or median and interquartile range (IQR) as appropriate. Categorical variables were presented as total number and percentage unless stated otherwise. No imputation was made for missing data. All analyses were performed using STATA 15.2.

Ethics approval

The University of British Columbia Clinical Research Ethics Board and Fraser Health Research Ethics Board approved this study. Owing to the retrospective and minimal-risk nature of the study, the need for informed consent was waived.

Results

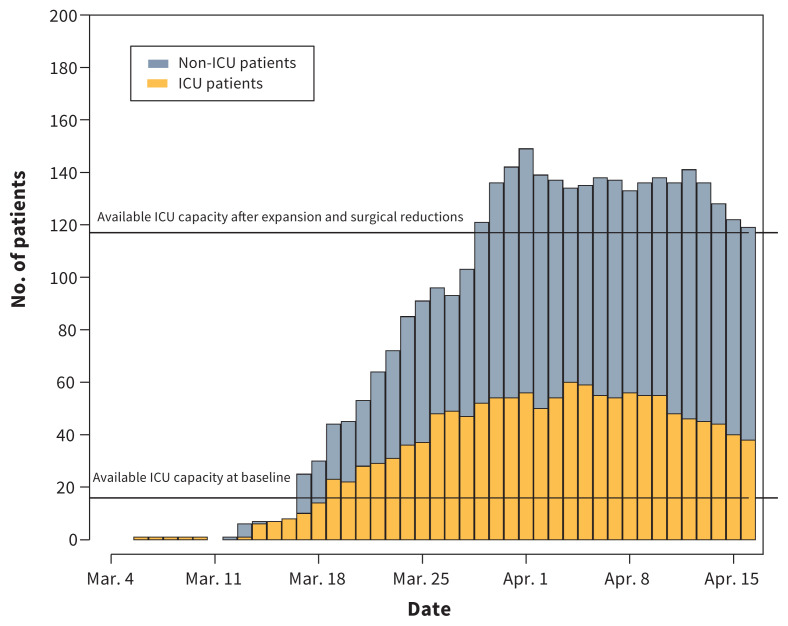

Between Feb. 21 and Apr. 14, 2020, we identified 117 critically ill patients with laboratory-confirmed SARS-CoV-2 infection admitted to an ICU in the region. There were no exclusions. The daily prevalence for patients admitted to hospital with COVID-19, stratified by admission to ICU, is presented in Figure 1. On a daily basis, a median of 40% (IQR 38%–45%) of hospital-admitted patients were admitted to the ICU.

Figure 1:

Epidemiologic curve of daily inpatient coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) prevalence, stratified by intensive care unit (ICU) admission. “Available ICU capacity at baseline” refers to available patient capacity above baseline occupancy. “Available ICU capacity after expansion and surgical reductions” refers to the COVID-19–specific measures that were introduced. These include physical bed expansion and newly available bed space from cancelling nonurgent and elective surgeries.

Eighty-eight (75.2%) patients were admitted from home, 25 (21.4%) patients were admitted from another hospital, and 4 (3.4%) were admitted from long-term care facilities. Baseline demographic and clinical characteristics are shown in Table 1 and are comparable to those in previous reports (Appendix 1, available at www.cmaj.ca/lookup/suppl/doi:10.1503/cmaj.200794/-/DC1). The median age of the patients was 69 (IQR 60–75) years, with a range of 23 to 92 years. Overall, 38 (32.5%) patients were female, and the mean duration of symptoms before ICU admission was 8 (SD 4.5) days. A total of 86 (73.5%) patients had at least 1 medical comorbidity. The most common comorbidities were hypertension (54 patients, 46.2%), dyslipidemia (43 patients, 36.8%) and diabetes mellitus (36 patients, 30.8%).

Table 1:

Baseline demographic and clinical characteristics of 117 critically ill patients with COVID-19 admitted to ICUs in Metro Vancouver, British Columbia

| Characteristic | No. (%) of patients* |

|---|---|

| Demographic characteristic | |

| Age, yr, median (IQR) | 69 (60–75) |

| Sex, female | 38 (32.5) |

| BMI, median (IQR)† | 28 (24–33) |

| Time from symptom onset to ICU admission, d, mean (± SD) | 8.0 (± 4.5) |

| APACHE II score, median (IQR)‡ | 18 (10–28) |

| SOFA score at admission, median (IQR)§ | 6 (2–11) |

| Enrolment site | |

| Quaternary or tertiary A | 39 (33.3) |

| Quaternary or tertiary B | 29 (24.8) |

| Quaternary or tertiary C | 21 (17.9) |

| Quaternary or tertiary D | 9 (7.7) |

| Community A | 13 (11.1) |

| Community B | 6 (5.1) |

| Comorbidity | |

| Hypertension | 54 (46.2) |

| Dyslipidemia | 43 (36.8) |

| Diabetes mellitus | 36 (30.8) |

| None | 31 (26.5) |

| Cardiovascular disease | 20 (17.1) |

| Current or former tobacco smoker | 16 (13.7) |

| Chronic kidney disease | 15 (12.8) |

| Asthma | 14 (12.0) |

| Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease | 8 (6.8) |

| Active malignancy | 7 (6.0) |

| Congestive heart failure | 4 (3.4) |

| Hemorrhagic or ischemic stroke | 4 (3.4) |

| Chronic liver disease | 2 (1.7) |

Note: APACHE = Acute Physiology and Chronic Health Evaluation, BMI = body mass index, COVID-19 = coronavirus disease 2019, ICU = intensive care unit, IQR = interquartile range, SD = standard deviation, SOFA = Sequential Organ Failure Assessment.

Unless stated otherwise.

BMI was recorded only for the 74 patients who underwent mechanical ventilation. Of these, 55 (74.3%) had data available.

The APACHE II score is a measure of illness acuity with possible scores ranging from 0 to 71. Higher scores indicate more severe illness and are associated with greater mortality. APACHE II scores were available for 95 (81.2%) patients.

The SOFA score is a measure of illness acuity with possible scores ranging from 0 to 24. Higher scores indicate more severe illness and are associated with greater mortality. SOFA scores on day 1 of ICU admission were available for 115 (98.3%) patients.

Laboratory results at ICU admission and for the first 3 days in the ICU are presented in Table 2. A baseline leukocyte count above 10.0 ×109/L was present in 35 (29.9%) patients, and 9 (7.7%) had counts below 4 ×109/L. Lymphocytopenia was common, with 79 (67.5%) patients having a lymphocyte count less than 1.0 ×109/L. A total of 37 (31.6%) patients had baseline serum creatinine values of 106 μmol/L or greater. Baseline serum lactate was 2.0 U/L or greater in 21 (17.9%) patients. A total of 67 (57.2%) had a peak d-dimer result greater than 500 μg/L during the first 3 days in the ICU with an overall median of 1560 (IQR 740–4000) μg/L. Overall, a total of 32 patients (27.4%) had either a peak troponin I level greater than 26 ng/L or a peak troponin T level greater than 0.02 ng/L during the first 3 days in the ICU.

Table 2:

Laboratory data at ICU admission and during ICU stay in 117 critically ill patients with COVID-19

| Variable | Laboratory data, median (IQR) | Reference |

|---|---|---|

| On admission to ICU | ||

| Leukocyte count, ×109/L | 8.1 (5.9–10.8) | 3.5–12.0 |

| Lymphocyte count, ×109/L | 0.8 (0.5–1) | 1.0–3.0 |

| Platelet count, ×109/L 215 | (161–271.5) | 150–400 |

| Serum creatinine level, μmol/L | 86 (70–114) | 50–110 |

| Total bilirubin level, μmol/L | 9 (6–14) | 3–22 |

| Direct bilirubin level, μmol/L | 3.5 (2–7) | 0–5 |

| Aspartate aminotransferase level, mU/mL | 63.5 (38–99) | 18–40 |

| Alanine aminotransferase level, mU/mL | 44 (27–88) | 17–63 |

| Lactate level, mmol/L | 1.5 (1.1–1.9) | 1–1.8 |

| First 3 days in ICU | ||

| Lowest platelet count, ×109/L | 190 (155–250) | 150–400 |

| Peak serum creatinine level, μmol/L | 101 (79–148) | 50–110 |

| Highest total bilirubin level, μmol/L | 10 (7–15) | 3–22 |

| Highest direct bilirubin level, μmol/L | 5 (3–9) | 0–5 |

| Highest d-dimer concentration, μg/L | 1560 (740–4000) | 0–229 |

| Highest ferritin level, ng/mL | 1125 (637–2058) | 15–400 |

| Highest C-reactive protein level, mg/L | 148 (87–232) | 0–10 |

| Highest creatine kinase level, U/L | 119 (49–255) | 25–200 |

| Highest troponin I level, ng/L | 15 (7–40) | < 26 |

| Highest troponin T level, ng/L | 0.02 (0.02–0.08) | 0–0.4 |

Note: COVID-19 = coronavirus disease 2019, ICU = intensive care unit, IQR = interquartile range.

The frequency of ICU interventions and therapies is shown in Table 3. The most frequent interventions were mechanical ventilation (74 patients, 63.2%), vasopressors (65 patients, 55.6%), neuromuscular blockade (50 patients, 42.7%) and high-flow nasal cannula (43 patients, 36.8%). The medians of the ratio between partial pressure of oxygen and fraction of inspired oxygen (PaO2:FiO2) and of static lung compliance after 24 hours of mechanical ventilation were 180 (IQR 148–216) and 35 (IQR 31–44) mL × cm H2O−1, respectively. No patients in our study received remdesivir, 1 (0.9%) patient received hydroxychloroquine and 4 (3.4%) patients received tocilizumab.

Table 3:

Management in the ICU and clinical outcomes in 117 critically ill patients with COVID-19

| Variable | No. (%) of patients* |

|---|---|

| ICU therapy | |

| Mechanical ventilation | 74 (63.2) |

| Vasopressors | 65 (55.6) |

| Neuromuscular blockade | 50 (42.7) |

| High-flow nasal cannula | 43 (36.8) |

| Prone ventilation | 21 (17.9) |

| Continuous renal replacement therapy | 16 (13.7) |

| Noninvasive positive-pressure ventilation | 15 (12.8) |

| Inhaled pulmonary vasodilators | 8 (6.8) |

| Extracorporeal membrane oxygenation | 3 (2.6) |

| Mechanical ventilation parameters 24 h after initiation, median (IQR)† | |

| Plateau pressure, cm H2O | 22 (20–24) |

| Positive end-expiratory pressure, cm H2O | 12 (10–14) |

| FiO2, % | 50 (40–60) |

| PaO2:FiO2 | 180 (148–216) |

| Tidal volume, mL/kg | 400 (350–450) |

| Compliance, mL × cm H2O−1 | 35 (31–44) |

| Pharmacologic therapy | |

| Steroids | 28 (23.9) |

| Tocilizumab | 4 (3.4) |

| Hydroxychloroquine | 1 (0.9) |

| Remdesivir | 0 (0.0) |

| Outcome | |

| Died in ICU | 18 (15.4) |

| Still in ICU | 12 (10.3) |

| Still in hospital (non-ICU) | 16 (13.7) |

| Discharged from hospital | 71 (60.7) |

| Reintubation within 48 h | 10 (8.5) |

| Readmission to ICU within 72 h | 6 (5.1) |

| ICU length of stay, d, median (IQR) | |

| Overall | 9 (5–21) |

| Patients discharged from ICU, n = 87 | 7 (3–16) |

| Patients discharged from hospital, n = 71 | 6 (3–11) |

| Deaths | 12 (7–18) |

| Hospital length of stay, d, median (IQR) | |

| Overall | 18 (11–30) |

| Patients discharged from ICU, n = 87 | 18 (10–32) |

| Patients discharged from hospital, n = 71 | 15 (8–22) |

| Deaths | 13 (8–18) |

| Duration of mechanical ventilation, d, median (IQR) | |

| Overall, n = 74 | 13.5 (8–22) |

| Extubated, n = 50 | 11.5 (6–18) |

| Patients discharged from ICU, n = 47 | 11 (6–16) |

| Patients discharged from hospital, n = 34 | 8 (5–13) |

| Deaths, n = 15 | 13 (10–20) |

Note: COVID-19 = coronavirus disease 2019, FiO2 = fraction of inspired oxygen, ICU = intensive care unit, IQR = interquartile range, PaO2 = partial pressure of oxygen.

Unless stated otherwise.

Complete mechanical ventilation parameters 24 hours after initiation were available for 48 (64.9%) of 74 patients who underwent mechanical ventilation.

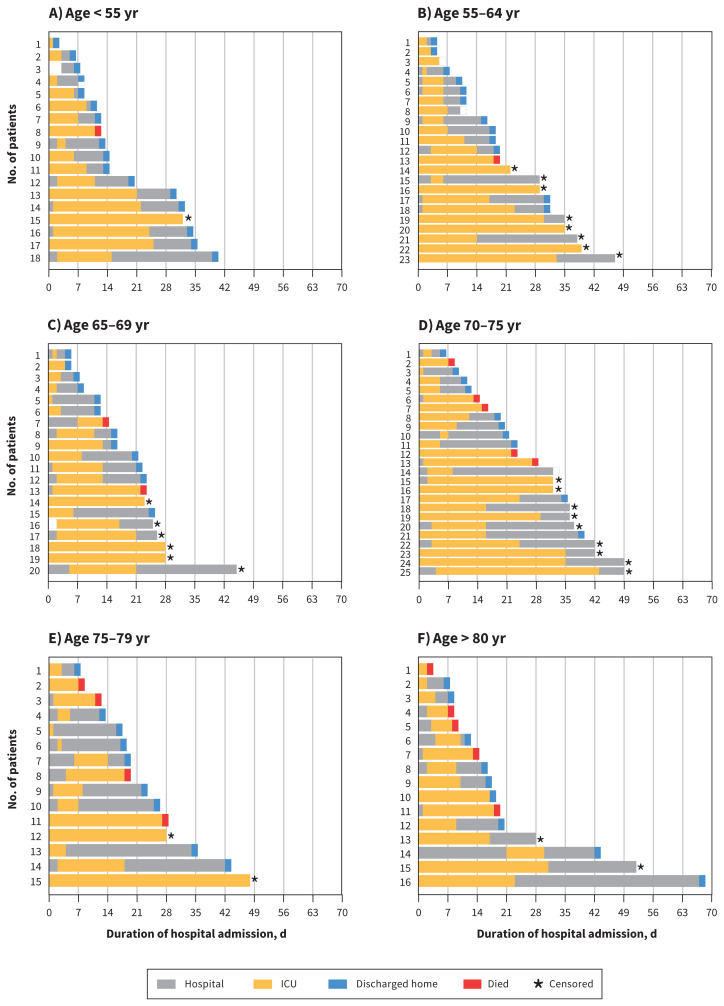

As of May 5, 2020, a total of 18 (15.4%) patients died, 12 (10.3%) remained in ICU, 16 (13.7%) were discharged from ICU but remained in hospital, and 71 (60.7%) were discharged home (Table 3, Figure 2). For the 28 patients still remaining in hospital, the median age was 69 (IQR 62–73) years, and the median ICU and hospital length of stay were 29 (IQR 18–33) days and 35 (IQR 28–42) days, respectively. The mortality for patients with an ICU outcome (either death or ICU discharge) was 18 of 105 (17.1%). Of the 18 patients who died, the median age was 75 (range 47–91) years, and 17 of 18 (94.4%) had at least 1 comorbidity. Two of the 18 patients who died had established do-not-intubate orders.

Figure 2:

Horizontal bar plots showing days of hospital admission for individual patients stratified by age group (A–F). *Censored refers to patients still in hospital (either ICU or non-ICU) at the time of study completion. Note: ICU = intensive care unit.

Of the 74 patients who underwent mechanical ventilation, 12 (16.2%) remained in ICU, 13 (17.6%) were discharged from ICU but remained in hospital, 34 (45.9%) were discharged home, and 15 (20.3%) died. Of the 16 patients who required continuous renal replacement therapy, 6 (37.5%) died, 7 (43.8%) were discharged from ICU and 3 (18.8%) were discharged home. All 16 (100%) required mechanical ventilation during their ICU stay.

Interpretation

In this case series of critically ill patients with laboratory-confirmed SARS-CoV-2 infection admitted to 1 of 6 ICUs in Metro Vancouver, the overall mortality was appreciably lower than in previously published studies, despite comparable baseline patient characteristics and a higher proportion of patients with completed hospital courses. Three-quarters of included patients in our study have been discharged from the ICU, and 61% have been discharged from hospital. In contrast to other studies, mortality did not markedly change for patients who underwent mechanical ventilation or for those who were discharged from the ICU.

Previous case series showed high mortality for critically ill patients admitted with COVID-19. In a retrospective case series of 1591 patients admitted to an ICU in Lombardy, Italy, the overall mortality was 26%.5 Importantly, most of the cohort remained in ICU at the time of publication. Mortality for patients who had an ICU outcome (death or discharge) was 61%. In a case series of 24 patients from Seattle the overall mortality was 50%, but mortality was 57% among patients with an ICU outcome.6 In a case series of 52 critically ill patients admitted to an ICU in Wuhan, China, the overall mortality was 62%, and mortality increased to 80% for patients with an ICU outcome.4 A case series from New York reported overall ICU mortality of 23%.7 Discharge from the ICU was not reported, so mortality with an ICU outcome could not be calculated. Mortality in patients with a hospital outcome (death or discharge) for critically ill patients in this case series was 78%.7 A strength of the current study is that it is a multicentre study involving all the ICUs in the Metro Vancouver area that have cared for patients with COVID-19, which includes a combination of quaternary, tertiary and community ICUs.

The patients in our study were similar in age, degree of comorbidities and reported severity of illness to those reported in the Lombardy, Seattle, New York and Wuhan case series. Patient severity of illness also appears to be comparable to other studies for measured covariates (e.g., PaO2:FiO2, compliance, APACHE II score and SOFA score). Patients in our study received invasive mechanical ventilation (63.2%) less frequently than in the Lombardy (88%), Seattle (75%) and New York (90%) studies, but more frequently than in the Wuhan (42%) cohort. The use of prone ventilation (17.9%) for our patients was similar to use in the Lombardy (27%), Seattle (28%) and Wuhan (12%) experiences.

In Metro Vancouver, we were initially hesitant to use high-flow nasal cannula early in the pandemic owing to concerns that it may cause aerosolization and transmission of SARS-CoV-2. However, after multidisciplinary review,10 and given that high-flow nasal cannula has been associated with lower mortality in hypoxemic respiratory failure,11 we decided to use high-flow nasal cannula in patients with COVID-19 under airborne precautions.

Despite the observed differences between patients and critical care interventions in these studies, it is unclear whether these solely account for the marked lower mortality that we report. We hypothesize that these encouraging results may be due to a broader system-level response that prevented an overwhelming surge of critically ill patients with COVID-19 from presenting to our hospitals and ICUs. On a daily basis, about 40% of our total hospital COVID-19 population was admitted to an ICU, reflecting the ready availability of ICU capacity. Although the authors do not report daily percentages, the recently published New York study reported that 22% of their total population of hospital-admitted patients had been admitted to the ICU at some point.7 Similar to our experience in Metro Vancouver, other jurisdictions also had large system-level responses. However, these occurred after their hospitals were already experiencing a surge of patients with COVID-19.12,13 Preventing our ICUs from being overwhelmed allowed them to be appropriately resourced to provide optimal critical care to patients with COVID-19. Normal ratios of health care worker to patient were maintained, personal protective equipment supply was sufficient and health care workers did not need to provide care that was outside of their normal scope of practice. Prioritized resource allocation was not required, and all patients with goals of care consistent with ICU admission received critical care.

Availability of critical care resources was assured through both enacting public health measures that reduced the incidence of COVID-19, and provincial and regional planning to increase available ICU capacity. In addition to social distancing, public health measures were enacted in a staged fashion starting with the beginning of the spring school break on Mar. 14.3 The following were banned on Mar. 16: mass gatherings of more than 50 people, entry of foreign nationals into Canada and symptomatic individuals from flights to Canada.3 At that time, returning international flights were restricted to 4 national airports.3 Additional public health measures included the following: declaring a provincial public health emergency and implementing public health orders of traveller self-isolation on Mar. 17, declaring a provincial state of emergency and implementing food and drink service restrictions on Mar. 18, closing the border between the United States and Canada to nonessential travel on Mar. 20, and closing personal service establishments on Mar. 21.3 Taken together, these measures resulted in a flattening of the epidemiologic prevalence curve in British Columbia, which is reflected in Figure 1.

Simultaneously, critical care capacity was substantially increased. On Mar. 16, nonurgent and elective surgeries were cancelled, reducing the need for postoperative intensive care beds. This also opened cardiac surgery ICU and postanesthesia care unit beds to be repurposed, increasing the number of available critical care beds in the COVID-19 centres in Metro Vancouver. The prepandemic available ICU capacity, based on prior occupancy rates, and the new available ICU capacity after expansion and surgical reductions are displayed in Figure 1.

Even in the absence of a pandemic, greater capacity strain at the time of ICU admission can lead to increased inpatient mortality,14 particularly with patients who are more severely ill.15 Furthermore, jurisdictions with high rates of patients with COVID-19 have been shown to have increased deaths not related to COVID-19, possibly reflecting the consequences of an overwhelmed medical system.16,17 Owing to the combination of public health measures and building additional ICU surge capacity, we were able to meet the demands of all patients with COVID-19 who presented to hospital and critical care. Another important observation from our study is that low mortality was observed in the absence of routine use of targeted pharmacologic therapies for COVID-19.18 Our findings do not disprove the efficacy of proposed pharmacologic therapies for critically ill patients with COVID-19. However, we highlight that excellent clinical outcomes can be achieved with accessible and high-level supportive critical care, independent of targeted pharmacologic therapies.

Limitations

This study has several important limitations. As this is a case series, causal effects for the reported outcomes cannot be determined. Any link between capacity and system-wide measures and the observed outcomes is speculative. The follow-up time is short relative to the course of the disease, and the reported mortality and length-of-stay data in this study could change. Finally, outcomes are not available for all patients as some still remained in ICU and hospital at the time of censoring.

Conclusion

In this case series of critically ill patients with laboratory-confirmed SARS-CoV-2 infection admitted to ICUs in Metro Vancouver, Canada, the overall mortality was 15%. This is lower than previously reported, despite low use of targeted pharmacologic therapies, which may reflect manageable patient burden owing to regional public health measures and additional ICU surge capacity.

Acknowledgements

The authors thank Steven Reynolds, Neilson McLean and Demetrious Sirounis for support in accessing data. They also thank the nurses and staff in the intensive care units for their care and dedication to our patients. Finally, they thank their patients for their participation in this study. None of these individuals were compensated for their role in the study.

Footnotes

Competing interests: None declared.

This article has been peer reviewed.

Contributors: Donald Griesdale, Anish Mitra and Nicholas Fergusson had full access to all the data in the study and take responsibility for the integrity of the data and the accuracy of the data analysis. Anish Mitra and Nicholas Fergusson equally contributed to this work as first coauthors. Anish Mitra, Nicholas Fergusson, Dean Chittock and Donald Griesdale contributed to the concept and design. All of the authors acquired, analyzed or interpreted the data. Anish Mitra, Nicholas Fergusson and Donald Griesdale drafted the manuscript. Anish Mitra, Nicholas Fergusson and Donald Griesdale performed the statistical analysis. All authors were involved in the critical revision of the manuscript, gave final approval of the version to be published and agreed to be accountable for all aspects of the work.

Funding: Donald Griesdale is supported through a Health Professional-Investigator Award from the Michael Smith Foundation for Health Research. Mypinder Sekhon is supported through the Vancouver Coastal Health Research Institute Clinician Scientist Award.

Data sharing: A deidentified data set is held on a secure server at Vancouver Coastal Health. The data-sharing agreement prohibits the data from being publicly available. Data requests may be granted provided there is an appropriate data-sharing agreement which would encompass both Vancouver Coastal Health and Fraser Health authorities. The data analysis code (STATA v15.2) is available on request.

References

- 1.WHO director-general’s opening remarks at the media briefing on COVID-19 — 11 March 2020. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2020. Mar. 11 Available: www.who.int/dg/speeches/detail/who-director-general-s-opening-remarks-at-the-media-briefing-on-covid-19---11-march-2020 (accessed 2020 Apr. 21). [Google Scholar]

- 2.Coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-2019) situation report — 92. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2020. Apr. 21 Available: www.who.int/emergencies/diseases/novel-coronavirus-2019/situation-reports (accessed 2020 Apr. 21). [Google Scholar]

- 3.BC COVID-19 dashboard. Vancouver: BC Centre for Disease Control; updated 2020 May 20. Available: www.bccdc.ca/health-info/diseases-conditions/covid-19/data (accessed 2020 May 20). [Google Scholar]

- 4.Yang X, Yu Y, Xu J, et al. Clinical course and outcomes of critically ill patients with SARS-CoV-2 pneumonia in Wuhan, China: a single-centered, retrospective, observational study. Lancet Respir Med 2020;8:475–81. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Grasselli G, Zangrillo A, Zanella A, et al. Baseline characteristics and outcomes of 1591 patients infected with SARS-CoV-2 admitted to ICUs of the Lombardy Region, Italy. JAMA 2020. Apr. 6 [Epub ahead of print]. 10.1001/jama.2020.5394. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bhatraju PK, Ghassemieh BJ, Nichols M, et al. COVID-19 in critically ill patients in the Seattle region — case series. N Engl J Med 2020. Mar. 30 [Epub ahead of print]. 10.1056/NEJMoa2004500. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Richardson S, Hirsch JS, Narasinhan M, et al. Presenting characteristics, comorbidities, and outcomes among 5700 patients hospitalized with COVID-19 in the New York City Area. JAMA 2020. Apr. 22 [Epub ahead of print]. 10.1001/jama.2020.6775. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Knaus WA, Draper EA, Wagner DP, et al. APACHE II — a severity of disease classification system. Crit Care Med 1985;13:818–29. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Vincent JL, Moreno R, Takala J, et al. The SOFA (Sepsis-related Organ Failure Assessment) score to describe organ dysfunction/failure. Intensive Care Med 1996;22:707–10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.High-flow oxygen during the COVID-19 pandemic. Vancouver: British Columbia Center for Disease Control; updated 2020 Apr. 15. Available: www.bccdc.ca/Health-Professionals-Site/Documents/COVID19_HighFlowOxygenRecommendations.pdf (accessed 2020 May 7). [Google Scholar]

- 11.Frat JP, Thille AW, Mercat A, et al. High-flow oxygen through nasal cannula in acute hypoxemic respiratory failure. N Engl J Med 2015;372:2185–96. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Grasselli G, Pesenti A, Cecconi M. Critical care utilization for the COVID-19 outbreak in Lombardy, Italy: early experience and forecast during an emergency response. JAMA 2020. Mar. 13 [Epub ahead of print]. 10.1001/jama.2020.4031. [Epub ahead of print]. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Wu Z, McGoogan JM. Characteristics of and important lessons from the coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) outbreak in China: summary of a report of 72 314 cases from the Chinese Center for Disease Control and Prevention. JAMA 2020; Feb. 24 [Epub ahead of print]. 10.1001/jama.2020.2648. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Fergusson NA, Ahkioon S, Nagarajan M, et al. Association of intensive care unit occupancy during admission and inpatient mortality: a retrospective cohort study. Can J Anaesth 2020;67:213–24. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Wilcox ME, Harrison D, Patel A, et al. Higher ICU capacity strain is associated with increased acute mortality in closed ICUs. Crit Care Med 2020;48:709–16. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Lazzerini M, Barbi E, Apicella A, et al. Delayed access or provision of care in Italy resulting from fear of COVID-19. Lancet Child Adolesc Health. 2020;4:e10–11. 10.1016/S2352-4642(20)30108-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Covid 19’s death toll appears higher than official figures suggest. The Economist 2020. Apr. 4 Available: www.economist.com/graphic-detail/2020/04/03/covid-19s-death-toll-appears-higher-than-official-figures-suggest (accessed 2020 Apr. 21).

- 18.Clinical Reference Group Recommendation: therapies for COVID-19. Vancouver: British Columbia Center for Disease Control; 2020:1–3. [updated 2020 Apr. 12]. Available: www.bccdc.ca/Health-ProfessionalsSite/Documents/Recommendation_Unproven_Therapies_COVID-19.pdf (accessed 2020 Apr. 21). [Google Scholar]