KEY POINTS

Illness and hospital admissions directly related to coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) have been infrequent for children and young people; however, pandemic-related service closures have resulted in limited access to primary and secondary health care, parental fear of seeking health care, closures of daycares and schools, and employment and financial instability.

Adverse childhood experiences, including family violence, nonaccidental trauma and mental illness, are expected to increase during lockdown and worsen during the anticipated economic recession.

Safe care must continue to be provided in the community and in hospital, virtually or, for select cohorts, in person.

Clear and transparent communication with children, young people and their families is needed regarding uncertainties about ongoing care and, where applicable, the reorganization of services.

Social re-introduction policies, resumption of normal health care services and changes to services should be informed by systematically collected data and understanding of families’ lived experiences.

As of June 21, 6982 individuals in Canada aged 19 years and younger, hereafter referred to as children and young people, had tested positive for severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2) infection, leading to 98 hospital admissions and 20 intensive care admissions, but no deaths.1 Aside from cases of pediatric multisystem inflammatory syndrome temporally associated with SARS-CoV-2 (PIMS-TS), for which understanding is still developing,2 worldwide, children and young people have been more mildly affected by coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) than adults.3

Countries that have seen substantial disruption to usual medical services and widespread public health measures related to COVID-19 are likely to see both immediate and long-term indirect effects of the pandemic on health. The potential adverse effects on children and young people’s health may be underappreciated. We discuss how limited access to primary and secondary health care, parental fear of seeking health care, daycare and school closures, employment and financial instability, and greater risk of exposure to adverse childhood experiences may lead to increased morbidity and mortality. We consider potential mitigation strategies, including restructuring the way in which health care is delivered for children and young people.

What are the potential indirect physical health effects of the COVID-19 pandemic in children and young people?

Pandemic-related service closures, warnings and public health measures have led to substantially reduced use of health care services by children, young people and families. In the United Kingdom,4 Ireland5 and Italy,6 routinely collected admissions data show decreases of up to 75% in pediatric emergency department attendances and admissions during lockdown compared with the same period in previous years. The Hospital for Sick Children in Toronto reported a reduction in pediatric emergency department visits by 30% in March and 62% in April 2020 compared with 2019 (Dr. Karim Jessa, The Hospital for Sick Children, Toronto, Ont: personal communication, 2020).

Delayed presentations for pediatric illness have been reported. In one 5-day period across 5 hospitals in Italy, 12 cases of delayed access to hospital for illnesses not related to COVID-19 were reported: 6 of the patients required intensive care and 4 died.6 Similar data emerging from low- and middle-income countries appear to align with this trend. A tertiary care pediatric hospital in India, for example, reported an increase in the number of children who presented with severe diabetic ketoacidosis in April 2020 during lockdown compared with the previous year.7 Delays in bringing children and young people to medical attention may be due to parental fears of exposure to SARS-CoV-2 in hospital facilities or on public transit, lack of child care for other children (especially for single parents), inability to access primary care because of service closures, or changes to hospital visitation policies that would see parents having to leave their children alone in hospital.

However, the effects of national lockdown policies, including quarantine and restricted travel, on children and young people’s social patterns and play opportunities have probably led to reduced transmission of other commonly acquired pathogens, reduced exposure to triggers for common respiratory problems or allergy, and possibly reduced accidental trauma.

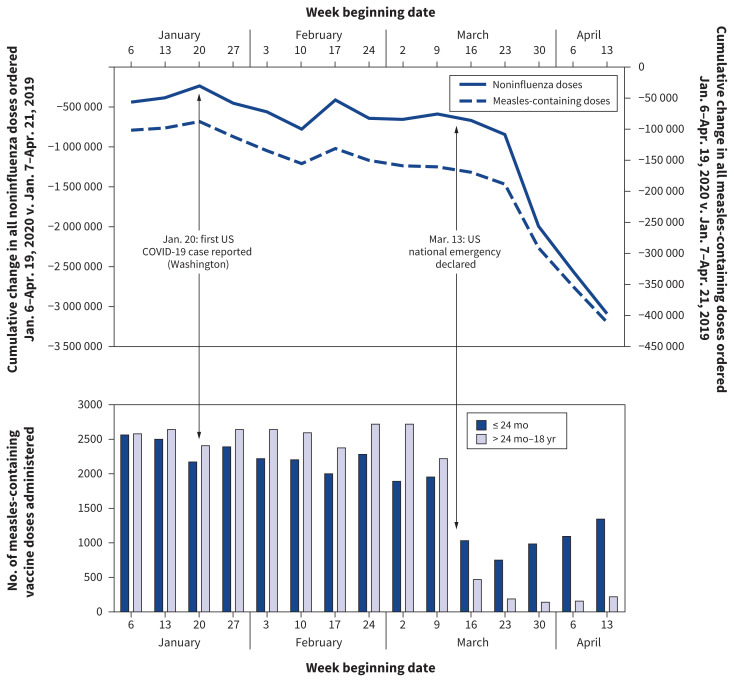

Closures of primary health care facilities because of inability to practise optimal infection control, combined with parental fear of attending health care settings, have led to widespread omission or delay of scheduled childhood vaccinations, which threatens reduced herd immunity and a resurgence of preventable infectious disease outbreaks in the future. A recent survey of 1000 pediatricians across the United States found that, compared with 2 months prior, vaccination rates decreased the week of Apr. 5, 2020, by 50% for measles, mumps and rubella and by 42% for diphtheria and whooping cough.8 The US Vaccines for Children Program recently reported a substantial decrease in noninfluenza childhood vaccinations, including measles, mumps and rubella, from the period covering Jan. 6–Apr. 19, 2020, compared with 2019 (Figure 1).9

Figure 1:

Weekly changes in Vaccines for Children Program provider orders* and Vaccine Safety Datalink doses administered† for routine pediatric vaccines — United States, Jan. 6–Apr. 19, 2020.9 *Vaccines for Children Program data represent the difference in cumulative doses of program-funded non-influenza and measles-containing vaccines ordered by health care providers at weekly intervals between Jan. 7–Apr. 21, 2019, and Jan. 6–Apr. 19, 2020. †Vaccine Safety Datalink data depict weekly measles-containing vaccine doses administered by age group (age ≤ 24 mo and > 24 mo–18 yr).

On May 22, the World Health Organization reported that routine childhood vaccination services had been suspended or postponed in 68 lower-income countries, affecting more than 80 million children under the age of 1 year, in part owing to a lack of transport of vaccines between countries and health care personnel. 10 This will reduce herd immunity to common infectious diseases of childhood globally.

Further harms may arise as routine child health checks are missed. Missed developmental assessments, for example, are particularly concerning given that about 15% of children have a delay in at least 1 domain of development, and early identification has been shown to improve cognitive development and medical outcomes.11

What are the potential social and mental health effects for children, young people and families?

Adverse childhood experiences — such as maltreatment, poverty and food insecurity — have been associated with mental health problems, obesity and cardiovascular disease in later life.12 Such experiences are likely to be more common for children and young people experiencing mandated social isolation, particularly for new refugees, marginalized families and those living in Indigenous communities, who already live with inadequate housing conditions, financial strain and food insecurity.13

Restrictions and cancellation of visits by child welfare services to at-risk families, and the potential for reduced supervised visits from birth parents to their children in foster care (e.g., mothers who continue to breastfeed under these supervisory visits), may add to harms. As the economic recession deepens, an increase in family violence is expected,14 which is likely to be associated with greater nonaccidental injury15 and mental trauma in children and young people.16 Existing economic and health inequities are likely to worsen.

In March, the United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization reported that more than 1.19 billion students across 150 countries were out of school as a result of governmental lockdown policies. Inability to attend school will lead to greater food insecurity for many children who depend on school meals, and loss of a place of safety for vulnerable children and those in care. School closures also cause upheaval in families’ lives as parents struggle to support their children’s educational needs while balancing employment demands and child care demands or dealing with financial uncertainty. An Italian survey of 245 mothers with children aged 2–5 years reported disrupted sleep schedules, boredom and decreased self-control with higher rates of emotional and behavioural problems in both mothers and their children as a result of nationwide lockdown.17

Physical distancing and lockdown requirements mean that children and young people have lost social interactions with others, may lack a structured routine and are likely less physically active. Repeat surveys of 2426 children and adolescents (6–17 yr) from 5 schools in Shanghai, China, showed a reduction of 7.3 hours per week in physical activity and an increase in 30 hours per week of screen time when comparing lifestyle patterns before and after implementation of pandemic public health measures.18 Prolonged screen time can compound feelings of difficulty concentrating, sadness and irritability, as already reported by adolescents in China, leading to signs of early depression and anxiety.19

The implications of physical distancing and lockdown orders are even greater for children with additional health care needs, such as support services for developmental difficulties — which may be stopped or reduced — or home oxygen, the supply of which may be threatened. Furthermore, families of children with additional medical needs may have had to make a difficult decision as to whether to continue to allow support workers into their homes to assist with essential medical care — often with inadequate personal protective equipment — or to assume sole responsibility for their child’s care needs with little respite.

Across Canada, policies mandating increased pay for essential health workers, including registered nurses and personal support workers, may force families to find additional funds to pay for necessary services, as there has been no increase in government-funded family budgets, such as Ontario’s Special Services at Home or Enhanced Respite for Children who are Medically Fragile and/or Technology Dependent programs.20 Health care workers in Italy have reported difficulties among families forced to care for children and adolescents with neurodevelopmental disorders at home without assistance,21 as well as increased rates of violent conduct, nonsuicidal self-injury and suicide attempts in young people.22

How can we safely provide care to children, young people and families during the pandemic?

Develop responsive and adaptive health care systems

Family doctors and pediatricians must communicate to parents and key workers, including daycare workers, teachers and social workers, that health services are open and accessible if a child or young person needs them. Essential health services must continue to be provided safely. Box 1 outlines which outpatient services should be delivered in person and which could be offered through virtual care.23

Box 1:

Essential outpatient services to prioritize for children and young people during the COVID-19 pandemic

In-person visit

Vaccinations, particularly for at-risk populations

Newborn care, including weight checks, jaundice and feeding assessments

Concerns with failure to thrive

Mild injuries, to avoid a visit to the emergency department

Acute illness

Maltreatment concerns

Screening programs (e.g., hearing screening)

Essential medicine delivery (e.g., chemotherapy)

Virtual visit

Developmental surveillance (e.g., 18-month check)

School, learning or behavioural concerns

Chronic disease management (e.g., type 1 diabetes, epilepsy and asthma)

Prescription refills

New or worsening mental health concerns

Note: COVID-19 = coronavirus disease 2019.

Hospital-based pediatric services should work proactively with children, young people and families to find alternative arrangements for specialty care. These include, for example, moving the location of infusion rooms for those who require chemotherapy or biologics to areas where exposure to SARS-CoV-2 is low, and restructuring secondary care services to community-based outreach services (e.g., for patients with eating disorders) or delivering vital therapies (e.g., physiotherapy, occupational therapy and cognitive behavioural therapy) using virtual platforms. Examples of innovation are already emerging, including the creation of virtual pediatric emergency departments at several children’s hospitals across Canada.24

Communicate clearly with children and families

Better understanding is needed regarding how families make decisions during pandemic measures about the complex needs of children and young people, so as to better support them. Both practical and personal considerations must be taken into account. Families may be appropriately reluctant to attend in-person visits, and careful explanation of the rationale behind the need for in-person attendance may be required. Practical approaches are needed for families with young children and children with medical needs whose families cannot adhere to strict directives.

Health care practitioners should be able to explain the rationale behind any recommendations made or changes to primary and secondary care services, to allow families to assess whether all the factors that they themselves consider important are being taken into account. Table 1 outlines common questions a health care provider may be asked and potential communication strategies to address them. Anticipating family concerns is key.

Table 1:

Approach to communicating uncertainties with families

| Uncertainty | Communication strategy |

|---|---|

| How will you keep my child safe in the clinic or hospital? | Anticipate family concerns, and communicate how the primary or secondary care setting is restructured, for example

|

| What will happen when I seek care? | Keep up to date on the policies and procedures of your facility and address how they may affect patients

|

| Why do I need to come to an in-person rather than a virtual visit? | Communicate the rationale for an in-person visit (e.g., physical examination) |

| How can I get to the clinic or hospital safely? | Ask patients what times are suitable for them, particularly in light of reduced public transportation service Offer free or reduced parking, if possible Consider pick-up and drop-off (shuttle) services with trusted providers |

| How have you made these decisions for my child? | Where relevant, explain the alternative processes that are occurring as a result of COVID-19 and discuss the risks and benefits in an open and transparent manner |

| Who can I ask if I have questions? | Provide your phone number or email for families to ask questions to reduce unnecessary in-person visits |

| What should I do to keep my family safe? | Suggest strategies for families, including

|

| What happens if someone in our household comes down with COVID-19? | Suggest strategies for families that consider their personal constraints, including

|

Note: COVID-19 = coronavirus disease 2019.

Age-appropriate public health messaging and communications about risk should be published to mitigate mental health effects of public health measures on children. Several resources have been developed to support positive parenting during the pandemic, and front-line workers should be encouraged to distribute resources such as these to families, children and young people (Figure 2, Box 2).

Figure 2:

Coronavirus disease 2019 fact sheet for 6- to 12-year-olds. Reproduced with permission from the COVID-19 Health Literacy Project (https://covid19healthliteracyproject.com/#).

Box 2:

Resources for caregivers and parents to explain the COVID-19 pandemic to children and young people

COVID-19 Health Literacy Project (multiple translations available) (https://covid19healthliteracyproject.com/#)

Canadian Paediatric Society. COVID-19 information and resources for pediatricians (www.cps.ca/en/tools-outils/covid-19-information-and-resources-for-paediatricians)

Caring for Kids. COVID-19 and your child (www.caringforkids.cps.ca/handouts/the-2019-novel-coronavirus-covid-19)

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Talking with children about coronavirus disease 2019 (www.cdc.gov/coronavirus/2019-ncov/daily-life-coping/talking-with-children.html)

UNICEF. Keeping children safe online during the COVID-19 pandemic — tips for parents and caregivers (www.unicef.org/laos/stories/keeping-children-safe-online-during-covid-19-pandemic)

Children’s Commissioner (UK). Children’s guide to coronavirus (www.childrenscommissioner.gov.uk/publication/childrens-guide-to-coronavirus)

Royal College of Paediatrics and Child Health (UK). COVID-19 — resources for parents and carers (www.rcpch.ac.uk/resources/covid-19-resources-parents-carers#downloadBox)

Note: COVID-19 = coronavirus disease 2019.

Make data-informed decisions

Data are critical to an effective pandemic response, and children and young people must not be forgotten. A better understanding is required of the multidirectional relations among children’s health and government, public health and societal responses to the pandemic. Patients and families should be involved in determining the goals of data generation and relevant outcomes related to health care delivery, education and social care.

Policies addressing the return to school and social activities need to weigh the physical and mental health of children and young people against virus transmissibility,25 and be communicated in a way that addresses the concerns of families. Currently, policies differ across Canada, with schools having reopened or partially reopened in some provinces and having remained closed for the remainder of the academic year in others. Social activity for children and young people during summer holidays, such as recreational camps, should incorporate detailed data collection processes to determine whether children and young people contract and spread SARS-CoV-2 locally, and with what impact to their home and community setting.

Well-designed, proactively administered surveys will help capture the lived experiences of children, young people and families, including assessment of financial hardship, housing and food insecurity, parental mental illness, and interparental conflict and violence. Careful estimation of economic hardship caused by public health interventions should inform government interventions, such as universal basic income, unconditional cash transfers to low-income families, or increases to funding for existing disability-support programs, to mitigate adverse childhood experiences.26

Real-time, national data on emergency department visits and hospital admissions, along with clear case definitions of delayed care, would facilitate early identification of delayed care (e.g., rising numbers of children with acute exacerbations of asthma, increase in seizure frequencies) and sequelae from COVID-19 (e.g., PIMS-TS). Such data would also allow for comparison of outcomes across time and place, and help researchers and policy-makers assess the effects of interventions and plan for later in this and future pandemics.

While local initiatives are underway, Canada should ideally implement a national surveillance system that captures physician-reported poor health outcomes related to delayed care, as has been established in the UK (www.rcpch.ac.uk/key-topics/covid-19) and New Zealand (www.otago.ac.nz/nzpsu/current-studies/#covid-19) supported by national pediatric associations.

Conclusion

Although severe COVID-19 seems to be rare in children and young people, this demographic group will likely experience a high burden of indirect physical, social and mental health effects related to reduced nonurgent care and general pandemic control measures. We owe it to our children and young people to proactively measure the indirect effects of the COVID-19 pandemic on their health and take steps to mitigate the collateral damage.

Acknowledgement

The authors thank Anne Fuller for her suggestions.

Footnotes

Competing interests: Neil Chanchlani declares a clinical research fellowship funded by Crohn’s and Colitis UK. No other competing interests were declared.

This article has been peer reviewed.

Contributors: Neil Chanchlani and Peter Gill contributed to the conceptualization and wrote the first draft. All of the authors contributed to writing and revising the article, gave final approval of the version to be published and agreed to be accountable for all aspects of the work.

Disclaimer: Neil Chanchlani is an associate editor for CMAJ and was not involved in the editorial decision-making process for this article.

References

- 1.Coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19): epidemiology update. Ottawa: Public Health Agency of Canada; updated 2020 June 15. Available: https://health-infobase.canada.ca/covid-19/epidemiological-summary-covid-19-cases.html (accessed 2020 June 21). [Google Scholar]

- 2.Riphagen S, Gomez X, Gonzalez-Martinez C, et al. Hyperinflammatory shock in children during COVID-19 pandemic. Lancet 2020;395:1607–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Dong Y, Mo X, Hu Y, et al. Epidemiology of COVID-19 among children in China. Pediatrics 2020;145:e20200702. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Isba R, Edge R, Jenner R, et al. Where have all the children gone? Decreases in paediatric emergency department attendances at the start of the COVID-19 pandemic of 2020. Arch Dis Child 2020. May 6 [Epub ahead of print]. 10.1136/archdischild-2020-319385. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 5.Dann L, Fitzsimons J, Gorman KM, et al. Disappearing act: COVID-19 and paediatric emergency department attendances. Arch Dis Child 2020. June 9 [Epub ahead of print]. 10.1136/archdischild-2020-319654. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Lazzerini M, Barbi E, Apicella A, et al. Delayed access or provision of care in Italy resulting from fear of COVID-19. Lancet Child Adolesc Health 2020;4:e10–1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Dayal D, Gupta S, Raithatha D, et al. Missing during COVID-19 lockdown: children with new-onset type 1 diabetes. Research Square 2020. May 13 [Epub ahead of print]. 10.21203/rs.3.rs-28594/v1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hoffman J. Vaccine rates drop dangerously as parents avoid doctor’s visits. The New York Times 2020. Apr. 23 Available: www.nytimes.com/2020/04/23/health/coronavirus-measles-vaccines.html (accessed 2020 Apr. 23).

- 9.Santoli JM, Lindley MC, DeSilva MB, et al. Effects of the COVID-19 pandemic on routine pediatric vaccine ordering and administration — United States, 2020. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep 2020;69:591–3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.At least 80 million children under one at risk of diseases such as diphtheria, measles and polio as COVID-19 disrupts routine vaccination efforts, warn Gavi, WHO and UNICEF [news release]. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2020. May 22 Available: www.who.int/news-room/detail/22-05-2020-at-least-80-million-children-under-one-at-risk-of-diseases-such-as-diphtheria-measles-and-polio-as-covid-19-disrupts-routine-vaccination-efforts-warn-gavi-who-and-unicef (accessed 2020 May 22). [Google Scholar]

- 11.Vitrikas K, Savard D, Bucaj M. Developmental delay: when and how to screen. Am Fam Physician 2017;96:36–43. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Danese A, Moffitt TE, Harrington H, et al. Adverse childhood experiences and adult risk factors for age-related disease: depression, inflammation, and clustering of metabolic risk markers. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med 2009;163:1135–43. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Willows N, Veugelers P, Raine K, et al. Associations between household food insecurity and health outcomes in the Aboriginal population (excluding reserves). Health Rep 2011;22:15–20. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Wong CA, Ming D, Maslow G, et al. Mitigating the impacts of the COVID-19 pandemic response on at-risk children. Pediatrics 2020. Apr. 21 [Epub ahead of print]. 10.1542/peds.2020-0973. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Huang MI, O’Riordan MA, Fitzenrider E, et al. Increased incidence of nonaccidental head trauma in infants associated with the economic recession. J Neurosurg Pediatr 2011;8:171–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Sprang G, Silman M. Posttraumatic stress disorder in parents and youth after health-related disasters. Disaster Med Public Health Prep 2013;7:105–10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Di Giorgio E, Di Riso D, Mioni G, et al. The interplay between mothers’ and children behavioral and psychological factors during COVID-19: an Italian study. PsyArXiv 2020. Apr. 30 [Epub ahead of print]. 10.31234/osf.io/dqk7h. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Xiang M, Zhang Z, Kuwahara K. Impact of COVID-19 pandemic on children and adolescents’ lifestyle behavior larger than expected. Prog Cardiovasc Dis 2020. April 30 [Epub ahead of print]. S0033-0620(20)30096-7. 10.1016/j.pcad.2020.04.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Xie X, Xue Q, Zhou Y, et al. Mental health status among children in home confinement during the coronavirus disease 2019 outbreak in Hubei Province, China. JAMA Pediatr 2020;e201619 [Epub ahead of print]. 10.1001/jamapediatrics.2020.1619. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ontario Ministry of Children, Community and Social Services. Temporary changes to the Special Services at Home (SSAH) and enhanced respite for medically fragile and/or technology dependent children programs [addendum]. Toronto: Queen’s Printer for Ontario; modified 2020 May 21. Available: www.children.gov.on.ca/htdocs/English/specialneeds/specialservices/addendum-april2020.aspx (accessed 2020 June 16). [Google Scholar]

- 21.de Girolamo G, Cerveri G, Clerici M, et al. Mental health in the coronavirus disease 2019 emergency — the Italian response. JAMA Psychiatry 2020. Apr. 30 [Epub ahead of print]. 10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2020.1276. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Cognigni M. An Italian paediatric department at the time of coronavirus: a resident’s point of view. Arch Dis Child 2020. Apr. 27 [Epub ahead of print]. 10.1136/archdischild-2020-319299. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Sharon R. Providing virtual care during a pandemic: a guide to telemedicine in the paediatric office [blog]. Ottawa: Canadian Paediatric Society; 2020. Mar. 26 Available: www.cps.ca/en/blog-blogue/virtual-care-during-a-pandemic (accessed 2020 Apr. 20). [Google Scholar]

- 24.Rosenfield D, Levinter J, Mizzi T, et al. Role for isolated emergency medicine physicians during a pandemic. CJEM 2020. May 5 [Epub ahead of print]. 10.1017/cem.2020.390. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Viner RM, Russell SJ, Croker H, et al. School closure and management practices during coronavirus outbreaks including COVID-19: a rapid systematic review. Lancet Child Adolesc Health 2020;4:397–404. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Brownell MD, Chartier MJ, Nickel NC, et al. PATHS Equity for Children Team. Unconditional prenatal income supplement and birth outcomes. Pediatrics 2016;137:e20152992. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]