Abstract

Purpose

Long non-coding RNAs (lncRNAs) have been shown to be involved in many human diseases. In this study, we aimed to reveal the role and molecular mechanism of lncRNA EPB41L4A-AS1 in type 2 diabetic mellitus (T2DM)-related inflammation.

Methods

To explore the relationships between the expression of EPB41L4A-AS1 and inflammatory factors in the blood of T2DM patients, we analyzed peripheral blood mononuclear cell (PBMC) expression microarrays of T2DM patients and expression microarrays of PBMC treated with lipopolysaccharide (LPS) from the GEO database. The relationship between EPB41L4A-AS1 and phospho-p65 was explored by Western blotting (WB) and immunofluorescence. The interactions between EPB41L4A-AS1 and myeloid differentiation factor 88 (MYD88) were also verified through quantitative real-time PCR, WB, and chromatin immunoprecipitation. Glycolysis and mitochondrial stress were detected by Seahorse.

Results

EPB41L4A-AS1 showed very low expression, which was significantly negatively correlated with levels of inflammatory factors in PBMCs of T2DM patients and PBMCs treated with LPS. These results were verified by cell experiments on PBMC and THP-1 cells. Knockdown of EPB41L4A-AS1 led to the phosphorylation and nuclear translocation of p65 and thus activated the NF-κB signaling pathway; it also reduced the enrichment of H3K9me3 in the MYD88 promoter and increased expression of MYD88. Overall, EPB41L4A-AS1 knockdown promoted the level of glycolysis and ultimately enhanced the inflammatory response.

Conclusion

EPB41L4A-AS1 knockdown activated the NF-κB signaling pathway through a MYD88-dependent regulatory mechanism, promoted glycolysis, and ultimately enhanced the inflammatory response. These results demonstrate that EPB41L4A-AS1 is closely associated with inflammation in T2DM, and that low expression of EPB41L4A-AS1 may be used as an indicator of chronic inflammation and possible diabetic vascular complications in T2DM patients.

Keywords: inflammation, diabetes, EPB41L4A-AS1, NF-κB, MYD88

Introduction

In recent years, type 2 diabetes mellitus (T2DM) has become epidemic in many developed and developing countries. Owing to its high incidence and severe complications, it represents a major global public health problem.1 Increasing evidence indicates that T2DM involves a chronic inflammatory response, that is, metabolism-induced inflammation.2 In T2DM, excessive glucose and free fatty acids stimulate islets and insulin-sensitive tissues, leading to a local inflammatory response and releasing cytokines and chemokines including IL-1β, tumor necrosis factor-α (TNF-α), CCL2, and CXCL8.3 Conversely, data from several studies suggest that inflammation can, in turn, promote the development of T2DM by inducing insulin resistance and inhibiting β-cell function.2,4 Clinically, recent findings show that leukocytes such as lymphocytes are significantly increased in T2DM patients, and that cytokines including IL-1β, IL-12, and TNF-α can regulate the release of insulin, affecting the sensitivity of surrounding tissues.5

Long non-coding RNAs (lncRNAs) are a class of non-coding RNAs that are usually longer than 200 nucleotides in length.6 Most lncRNAs have no protein‐coding capabilities, although a few of them may produce small functional peptides.7 In recent years, with the development of high-throughput sequencing technology, various functions of lncRNAs, including in transcription and post-transcriptional regulation, have gradually been discovered.8,9 To date, several lncRNAs related to T2DM have been reported. NONRATT021972, a lncRNA associated with the p38 mitogen-activated protein kinase (p38 MAPK) signaling pathway, influences TNF-α and contributes to the pathophysiologic processes of diabetes.10 The lncRNA growth-arrest specific transcript 5 (GAS5) regulates the insulin signaling pathway and modulates the decrease in glucose metabolism and insulin resistance involved in the induction of T2DM.11

LncRNA EPB41L4A-AS1 is located in chromosome 5q22.2. Early studies have shown that EPB41L4A-AS1 can encode a small peptide named TIGA1 (transcript induced by growth arrest 1). Ectopic expression of EPB41L4A-AS1 can inhibit the growth and proliferation of tumor cells.12 However, our previous research found that EPB41L4A-AS1 mainly functioned as an lncRNA and that it was closely associated with the regulation of cell metabolism.13,14 In tumor cells, low expression of EPB41L4A-AS1 was involved in p53-mediated tumor metabolic reprogramming, and promoted glycolysis and glutamine metabolism and the Warburg effect.13 Consistently, we also found that in early recurrent miscarriage (RM), upregulation of EPB41L4A-AS1 expression inhibited glycolysis in placental trophoblast cells, resulting in inhibition of the Warburg effect.14 It is well known that energy support is needed to activate the immune response, and that glycolysis is the main source of cellular energy. The regulatory effect of EPB41L4A-AS1 on glucose metabolism suggests that it may participate in the process of immune inflammation. However, the role of EPB41L4A-AS1 in T2DM-related inflammation is still unknown.

Here, we report that lncRNA EPB41L4A-AS1 regulates the inflammatory response of peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMC) in T2DM. We found that the expression of lncRNA EPB41L4A-AS1 showed significant negative correlations with inflammatory factors in both PBMC of T2DM patients and PBMC treated with lipopolysaccharide (LPS). EPB41L4A-AS1 knockdown increased expression of inflammatory factors under high-glucose and high-fat conditions and following LPS treatment. Furthermore, we demonstrated that in T2DM, EPB41L4A-AS1 knockdown could activate the NF-κB signaling pathway through a myeloid differentiation factor 88 (MYD88)-dependent regulatory mechanism, thereby increasing expression levels of inflammatory factors including IL-1β and IL-8.

Materials and Methods

Cell Culture and Induction

THP-1 cells were purchased from the China Center for Type Culture Collection. According to the Declaration of Helsinki, the extraction of human PBMCs was approved by the Bioethics Committee of Shenzhen International Graduate School of Tsinghua University (No. 2020–41). In addition, informed consent was obtained from every volunteer. PBMCs were derived from the blood of healthy volunteers and separated from peripheral blood by density gradient centrifugation at 600 RCF for 6 min. All cells were cultured in RPMI 1640 medium (Gibco, Life Technologies, Grand Island, NY, USA) supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum (Gibco, Life Technologies, Grand Island, NY, USA) in a 5% CO2 incubator at 37°C. Cells were stimulated with LPS (Sigma-Aldrich, Merck, Darmstadt, Germany) or high glucose (HG, Sigma-Aldrich, Merck, Darmstadt, Germany) plus palmitic acid (PA, Sigma-Aldrich, Merck, Darmstadt, Germany). THP-1 and PBMC cells were induced by treatment with 55 mM HG plus 250 μmol/L PA, or with 1 μg/mL LPS. For quantitative real-time PCR (qRT-PCR), shnc, shEPB41L4A-AS1-1, and shEPB41L4A-AS1-2 cells were induced by treatment with 55 mM glucose in combination with different concentrations of PA (125 μmol/L, 250 μmol/L, 500 μmol/L), or with 100 ng to 1 μg/mL LPS. For enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) experiments, shnc, shEPB41L4A-AS1-1, and shEPB41L4A-AS1-2 cells were induced with 55 mM glucose plus 250 μmol/L PA, or with 200 ng/mL LPS. In the experiments to detect NF-κB and MYD88 in EPB41L4A-AS1 knockdown cell lines induced by LPS, 200 ng/mL LPS was used.

All lentivirus-based short hairpin RNAs (shRNAs: shnc, shEPB41L4A-AS1-1, shEPB41L4A-AS2-2) were purchased from Shanghai Genechem Co., Ltd. (Shanghai, China). The lentivirus was co-transfected with polybrene 298 (Sangon Biotech, Shanghai, China), and 1 μg/mL puromycin (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA, USA) was added for screening of the control cell line (shnc) and knockdown cell lines (shEPB41L4A-AS1-1, shEPB41L4A-AS2-2). qRT-PCR was used to detect the knockdown efficiency of EPB41L4A-AS1 in shEPB41L4A-AS1-1 and shEPB41L4A-AS2-2 cell lines, and the shnc cell line was used as a control. Compared with shnc, the knockdown efficiency of EPB41L4A-AS1 in shEPB41L4A-AS1-1 and shEPB41L4A-AS2-2 cells reached about 70%. The shRNA sequences are shown in Supplemental Table 1. MYD88 was knocked down with MYD88-specific RNA interference. The short interfering RNA sequences are shown in Supplemental Table 2.

Bioinformatics Analysis and ELISA

Pathological data of T2DM patients (GDS3875, GDS3874) and LPS-induced PBMC data (GDS2856) were downloaded from the GEO database (https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/). The histone modification level of the MYD88 promoter region was analyzed using the ENCODE database (http://genome.ucsc.edu/). To obtain the cell lysates, cells were lysed with cell lysis buffer (50 mM Tris HCl [pH 8.0], 1% Triton X-100, and 4 M urea) (Sangon Biotech, Shanghai, China). And the cell lysis buffer was supplemented with a mixture of protease inhibitors (Roche) to extract proteins. The expression levels of human IL-1β and IL-8 in cell media and lysates was determined using an ELISA kit (Dakewe Biotech, Shenzhen, Guangdong, China).

qRT-PCR

A ReversTra Ace kit (TOYOBO, Osaka, Japan) was used to reverse transcribe total RNA into cDNA. qRT-PCR was performed using a SYBR® Green Real-time-PCR kit (TOYOBO, Osaka, Japan). To ensure accuracy and biological repeatability, all samples were analyzed in triplicate. ACTB was used as an internal control, and relative abundance was calculated using the 2−ΔΔCT method. The qRT-PCR primers are shown in Supplemental Table 3.

Western Blot (WB) Analysis

THP-1 shnc, shEPB41L4A-AS1-1, and shEPB41L4A-AS1-2 cells were either left untreated or treated with 200 ng/mL LPS for 6 h. Then, cells were lysed with cell lysis buffer (50 mM Tris HCl [pH 8.0], 1% Triton X-100, and 4 M urea) (Sangon Biotech, Shanghai, China) supplemented with a mixture of protease inhibitors (Roche) to extract proteins. Heat the samples at 100°C for 10 minutes to denature the cells. Lysates were separated by sodium dodecyl sulfate polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (Sangon Biotech, Shanghai, China) and transferred to nitrocellulose membranes (Sangon Biotech, Shanghai, China) for WB analysis. After blocking with bovine serum albumin, the membranes were incubated with the following primary antibodies: P65 (#8242), Phospho-p65 (#3033), MYD88 (#4283), GAPDH (#5174) (Cell Signaling Technology, Danvers, MA, USA). Membranes were washed in TBST for 10 min three times, incubated with horseradish peroxidase-conjugated rabbit secondary antibodies (#5450-0010, SeraCare Life Sciences, Milford, MA), then washed in TBST for 10 min four times. Finally, enhanced chemiluminescence (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA, USA) was used to visualize the protein bands.

Immunofluorescence and Confocal Assay

Transparent glass slides were placed at the bottom of six-well plates, coated with poly-D-lysine solution (Sangon Biotech, Shanghai, China) for 30 min, rinsed with phosphate-buffered saline, and dried. Cells (2 × 105 per well) were added and cultured with medium containing LPS for 6 h. The medium was aspirated, and cells were washed with PBS and fixed with 4% paraformaldehyde (Sangon Biotech, Shanghai, China) before being washed three more times with PBS and incubated with 0.1% Triton X-100 (Sangon Biotech, Shanghai, China) for 15 min. After blocking with 3% bovine serum albumin (Sangon Biotech, Shanghai, China) for 1 h, cells were incubated with phospho-p65 antibody (#3033, Cell Signaling Technology, Danvers, MA, USA) for 1 h, washed three times, and incubated with Alexa Fluor 488 (Abcam, Cambridge, UK) for 1 h. Cells were then observed under a laser confocal microscope (Olympus FV1000, Tokyo, Japan).

Chromatin Immunoprecipitation (ChIP) Assay

The bottoms of 10 cm dishes were coated with poly-D-lysine Solution (Sangon Biotech, Shanghai, China) for 30 min, then washed and dried. Cells were lysed with ChIP lysis buffer (5 mM EDTA, 50 mM Tris-HCl [pH 8.0], 0.1% deoxycholate, 150 mM NaCl, 1% Triton X-100, and proteinase inhibitor) (Sangon Biotech, Shanghai, China). After ultrasonication, the supernatants were taken and incubated with Dynabeads Protein G (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA, USA), and H3K9me3 (ab8898) and H3K27me3 (ab6002) (Abcam, Cambridge, UK) antibodies. DNA was purified and detected by qRT-PCR. The ChIP-qPCR primers are shown in Supplemental Table 4.

Glycolysis Measurements and Mitochondrial Respiration

Seahorse assay plates were coated with poly-D-lysine solution (Sangon Biotech, Shanghai, China) and then washed and dried. Cells were added, and the plates were placed in a 37°C, carbon dioxide-free incubator overnight. The appropriate kits (Agilent Technologies, Santa Clara, CA, USA) kits were used to detect extracellular acidification rate (ECAR) and oxygen consumption rate (OCR), respectively. All tests were performed in triplicate.

Statistical Analyses

All data are expressed as mean ± SD. SPSS was used for statistical analysis. Differences were compared using two-tailed Student’s t-tests; P<0.05 was considered to be statistically significant. Data were plotted with GraphPad Prism 7.0.

Results

Negative Correlations Between EPB41L4A-AS1 and Inflammatory Factors in Peripheral Blood of Diabetic Patients

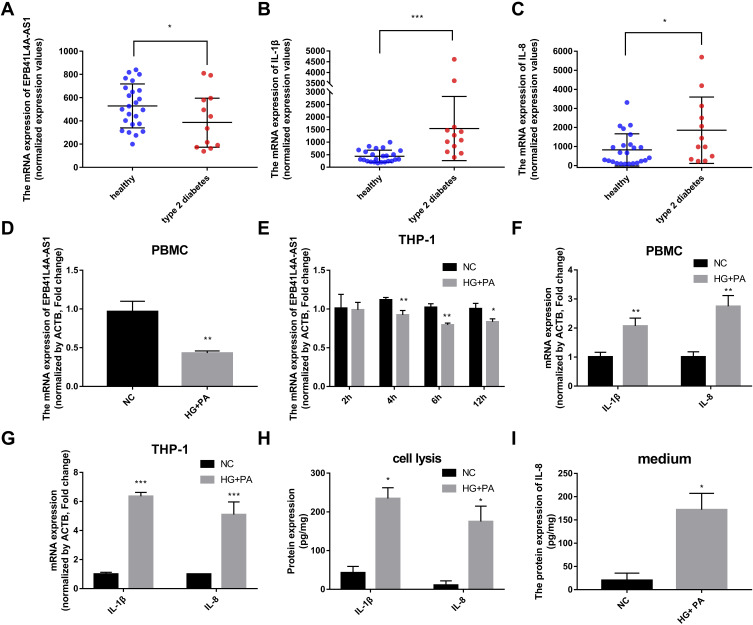

To explore the relationships between the expression of EPB41L4A-AS1 and inflammatory factors in the blood of T2DM patients, we analyzed PBMC expression microarrays of T2DM patients from the GEO database (GDS3875, GDS3874). Compared with healthy individuals, EPB41L4A-AS1 expression was significantly reduced in the PBMCs of T2DM patients (Figure 1A), and the expression of inflammatory factors IL-1β and IL-8 was upregulated (Figure 1B and C).

Figure 1.

Expression of EPB41L4A-AS1 and inflammatory factors in PBMC of T2DM patients, and experimental induction of PBMC and THP-1 cells by HG and high-fat conditions. (A) EPB41L4A-AS1 expression was decreased in the PBMC of T2MD patients compared with those of healthy individuals (GEO dataset GDS3875). (B–C) Expression of inflammatory factors IL-1β and IL-8 in PBMC of T2DM patients (GEO dataset GDS3874). (D) EPB41L4A-AS1 expression in PBMC after 55 mM HG + 250 μmol/L PA treatment for 12 h (n=3). (E) EPB41L4A-AS1 expression in THP-1 cells after 55 mM HG + 250 μmol/L PA treatment for 2–12 h (n=3). (F) IL-1β and IL-8 mRNA expression in PBMC after 55 mM HG + 250 μmol/L PA treatment for 12 h (n=3). (G) IL-1β and IL-8 mRNA expression in THP-1 cells after 55 mM HG + 250 μmol/L PA treatment for 6 h (n=3). (H) IL-1β and IL-8 protein expression in cell lysate of THP-1 cells after 55 mM HG + 250 μmol/L PA treatment for 6 h (n=3). (I) IL-8 protein expression in medium of THP-1 cells after 55 mM HG + 250 μmol/L PA treatment for 6 h (n=3). Data are shown as mean ± SD. *P<0.05, **P<0.01, ***P<0.001; Student’s t-test. HG, high glucose; NC, untreated; PA, palmitic acid.

To verify the connections between EPB41L4A-AS1 and inflammatory factors in T2DM, we used HG combined with PA to simulate the hyperglycemia and hyperlipidemia that occur in T2DM. PBMCs and THP-1 cells were treated with 55 mM HG plus 250 μmol/L PA. In both PBMC and THP-1 cells, EPB41L4A-AS1 was significantly decreased by treatment with HG plus PA (Figure 1D and E). After 6 h of this treatment, EPB41L4A-AS1 in THP-1 cells showed the greatest decrease in expression (Figure 1D). By contrast, the qRT-PCR results showed that the expression levels of IL-1β and IL-8 were significantly increased (Figure 1F and G). At the protein level, expression of IL-1β and IL-8 was significantly increased in the lysate of THP-1 cells, whereas the expression of IL-8 was significantly increased in the cell medium (IL-1β was not detected) (Figure 1H and I).

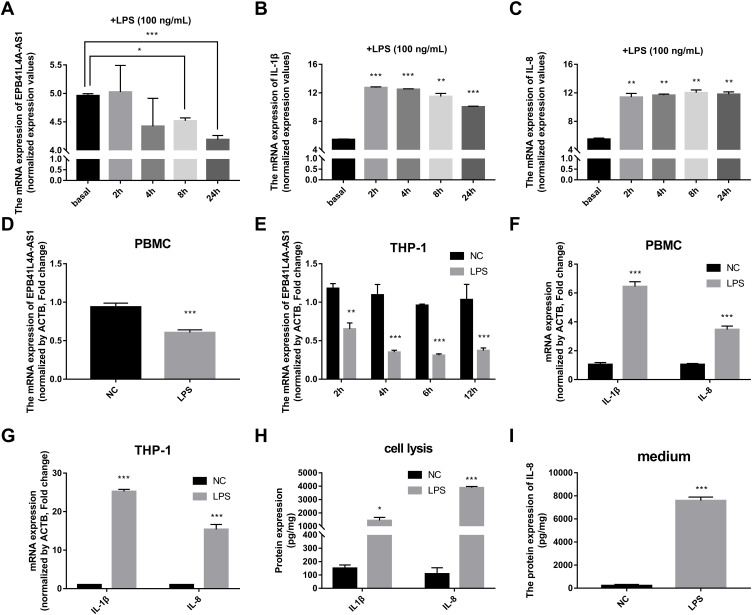

Negative Correlations Between EPB41L4A-AS1 and Inflammatory Factors Induced by LPS

It is well known that inflammatory factors and the chronic inflammatory responses that they mediate are inseparably involved in the process of T2DM.5 To further reveal the relationship between EPB41L4A-AS1 and inflammation in T2DM, we analyzed expression microarrays from the GEO database (GDS2856) of human PBMCs treated with 100 ng/mL LPS for 0, 2, 4, 8, and 24 h. The results showed that EPB41L4A-AS1 was significantly downregulated in PBMC after 8 h and 24 h LPS treatment (Figure 2A), and the inflammatory factors IL-1β and IL-8 were significantly upregulated (Figure 2B and C). In PBMC, after LPS treatment, the expression of EPB41L4A-AS1 and inflammatory factors displayed the contrary tendency. Therefore, based on analysis of PBMC expression microarrays of T2DM patients combined with the chronic inflammatory response in T2DM, we speculated that there are correlations between the expression of EPB41L4A-AS1 and inflammatory factors.

Figure 2.

Expression of EPB41L4A-AS1 and inflammatory factors in PBMC and THP-1 cells induced by LPS. (A–C) Expression of EPB41L4A-AS1 and inflammatory factors IL-1β and IL-8 at different times (basal, 2, 4, 8, and 24 h) during LPS treatment of PBMC (GEO dataset GDS2856). (D) EPB41L4A-AS1 expression in PBMC after 1 μg/mL LPS treatment for 24 h (n=3). (E) EPB41L4A-AS1 expression in THP-1 cells after 1 μg/mL LPS treatment for 2–12 h (n=3). (F) IL-1β and IL-8 expression in PBMC after 1 μg/mL LPS treatment for 24 h (n=3). (G) IL-1β and IL-8 expression in THP-1 cells after 1 μg/mL LPS treatment for 6 h (n=3). (H) IL-1β and IL-8 protein expression in cell lysate of THP-1 cells after 1 μg/mL LPS treatment for 6 h (n=3). (I) IL-8 protein expression in medium of THP-1 cells after 1 μg/mL LPS treatment for 6 h (n=3). NC indicates negative control. Data are shown as mean ± SD. *P<0.05, **P<0.01, ***P<0.001; Student’s t-test.

To reveal the relationships between expression of EPB41L4A-AS1 and inflammatory factors under the stimulation of inflammation at a cellular level, we used LPS to simulate a possible inflammatory reaction in T2DM. PBMC and THP-1 cells were treated with 1 μg/mL LPS for 24 h and 2–12 h, respectively. In both PBMC and THP-1 cells, expression of EPB41L4A-AS1 was significantly downregulated after 1 μg/mL LPS treatment. The expression level of EPB41L4A-AS1 reached its minimum after 6 h of LPS treatment in THP-1 cells (Figure 2D and E). We also analyzed the expression of inflammatory factors (IL-1β and IL-8) in PBMC and THP-1 cells after treatment with 1 μg/mL LPS at both the transcription and protein levels. The qRT-PCR results revealed that mRNA expression of IL-1β and IL-8 was significantly increased (Figure 2F and G). Besides, in THP-1 cell lysate, ELISA analyses verified that IL-1β and IL-8 showed the same expression pattern, whereas the expression of IL-8 was significantly increased in the medium of THP-1 cells (IL-1β was not detected) (Figure 2H and I). These results further verify the negative correlations between EPB41L4A-AS1 and inflammatory factors.

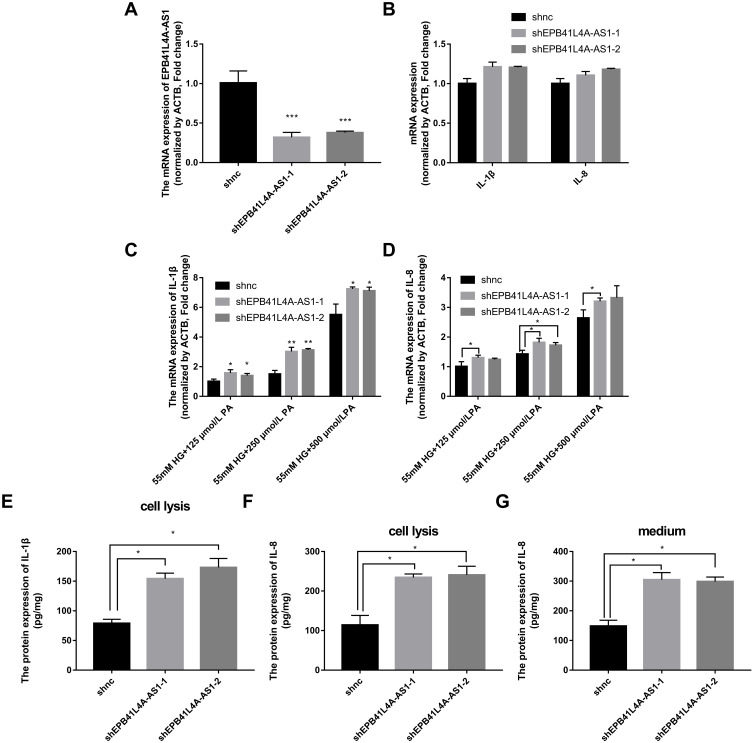

EPB41L4A-AS1 Knockdown Increased Expression of Inflammatory Factors Under HG and High-Fat Conditions

To verify the effects of EPB41L4A-AS1 expression on inflammatory factors, we performed gene knockdown of EPB41L4A-AS1 in THP-1 cells. Two cell lines were obtained, shEPB41L4A-AS1-1 and shEPB41L4A-AS1-2 (Figure 3A). Without inflammatory stimulation, the expression of IL-1β and IL-8 showed a less significant difference between shnc cell lines and EPB41L4A-AS1-knockdown cell lines (shEPB41L4A-AS1-1 and shEPB41L4A-AS1-2) (Figure 3B). Then, we used 55 mM glucose in combination with different concentrations of PA (125 μmol/L, 250 μmol/L, 500 μmol/L) to stimulate shnc, shEPB41L4A-AS1-1, and shEPB41L4A-AS1-2 cell lines; shnc was used as the negative control. The expression of inflammatory factors IL-1β and IL-8 was detected by qRT-PCR. We found that with increasing PA concentration, the mRNA expression levels of IL-1β and IL-8 in shEPB41L4A-AS1-1 and shEPB41L4A-AS1-2 cell lines became significantly higher than those in shnc (Figure 3C and D). In addition, consistent with the transcription level, the protein expression of IL-1β in cell lysate was also significantly increased (Figure 3E). However, no protein expression of IL-1β was detected in the medium. Compared with shnc, IL-8 was highly expressed in the cell lysates and media of shEPB41L4A-AS1-1 and shEPB41L4A-AS1-2 cells (Figure 3F and G). These results show that under HG and high-fat conditions, the absence of EPB41L4A-AS1 could significantly increase the expression of IL-1β at both mRNA and protein levels.

Figure 3.

Expression of inflammatory factors was increased in EPB41L4A-AS1-knockdown cell lines under HG and high-fat conditions. (A) EPB41L4A-AS1 expression in shnc, shEPB41L4A-AS1-1, and shEPB41L4A-AS1-2 cells (n=3). (B) IL-1β expression in shnc, shEPB41L4A-AS1-1, and shEPB41L4A-AS1-2 cells (n=3). (C) IL-1β mRNA expression in shnc, shEPB41L4A-AS1-1, and shEPB41L4A-AS1-2 cells treated with 55 mM glucose plus different concentrations of PA (125, 250, 500 μmol/L) (n=3). (D) IL-8 mRNA expression in shnc, shEPB41L4A-AS1-1, and shEPB41L4A-AS1-2 cells after treatment with 55 mM glucose plus different concentrations of PA (125, 250, 500 μmol/L) (n=3). (E) IL-1β protein expression in cell lysate of shnc, shEPB41L4A-AS1-1, and shEPB41L4A-AS1-2 cells after 55 mM glucose plus 250 μmol/L PA treatment (n=3). (F–G) IL-8 protein expression in cell lysate and media of shnc, shEPB41L4A-AS1-1, and shEPB41L4A-AS1-2 cells after 55 mM glucose plus 250 μmol/L PA treatment (n=3). Data are shown as mean ± SD. *P<0.05, **P<0.01, ***P<0.001; Student’s t-test.

EPB41L4A-AS1 Knockdown Increased Expression of Inflammatory Factors Under LPS Treatment

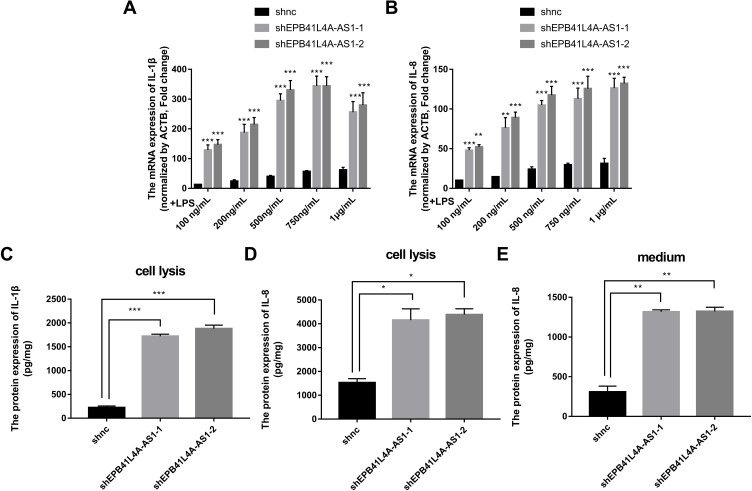

To verify the correlations between EPB41L4A-AS1 and LPS-induced inflammation, shnc, shEPB41L4A-AS1-1, and shEPB41L4A-AS1-2 cells were treated with LPS at different concentrations; the shnc cells were used as a negative control. Expression of IL-1β and IL-8 was detected by qRT-PCR. With increasing LPS concentration, the expression levels of IL-1β and IL-8 in the shnc, shEPB41L4A-AS1-1, and shEPB41L4A-AS1-2 cell lines showed an increasing trend. However, IL-1β and IL-8 showed a significantly greater gincrease in expression in the shEPB41L4A-AS1-1 and shEPB41L4A-AS1-2 cell lines than in shnc cells. The greatest differences between the expression levels of IL-1β and IL-8 in shnc cells and those in shEPB41L4A-AS1-1 and shEPB41L4A-AS1-2 cells were observed after treatment with 200 ng LPS (Figure 4A and B). These results show that EPB41L4A-AS1 knockdown increased expression of inflammatory factors at the mRNA level under LPS treatment.

Figure 4.

Expression of inflammatory factors was increased in EPB41L4A-AS1-knockdown cell lines under LPS treatment. (A–B) IL-1β and IL-8 mRNA expression in shnc, shEPB41L4A-AS1-1, and shEPB41L4A-AS1-2 cells after treatment with different concentrations of LPS (100 ng to 1 μg) for 6 h (n=3). (C–D) IL-1β and IL-8 protein expression in cell lysate of shnc, shEPB41L4A-AS1-1, and shEPB41L4A-AS1-2 cells after 200 ng/mL LPS treatment for 6 h (n=3). (E) IL-8 protein expression in media of shnc, shEPB41L4A-AS1-1, shEPB41L4A-AS1-2 cells after 200 ng/mL LPS treatment for 6 h (n=3). Data are shown as mean ± SD. *P<0.05, **P<0.01, ***P<0.001; Student’s t-test.

To further verify the effects of EPB41L4A-AS1 expression on inflammatory factors under LPS treatment at the protein level, ELISA was performed to detect the expression of inflammatory factors in cell lysates and media of shEPB41L4A-AS1-1, shEPB41L4A-AS1-2, and shnc cells. With 200 ng LPS treatment, IL-1β and IL-8 were more highly expressed in the cell lysates of shEPB41L4A-AS1-1 and shEPB41L4A-AS1-2 cells compared with shnc cells (Figure 4C and D). Similarly, the expression of IL-8 in the media of shEPB41L4A-AS1-1 and shEPB41L4A-AS1-2 cells was significantly increased (Figure 4E).

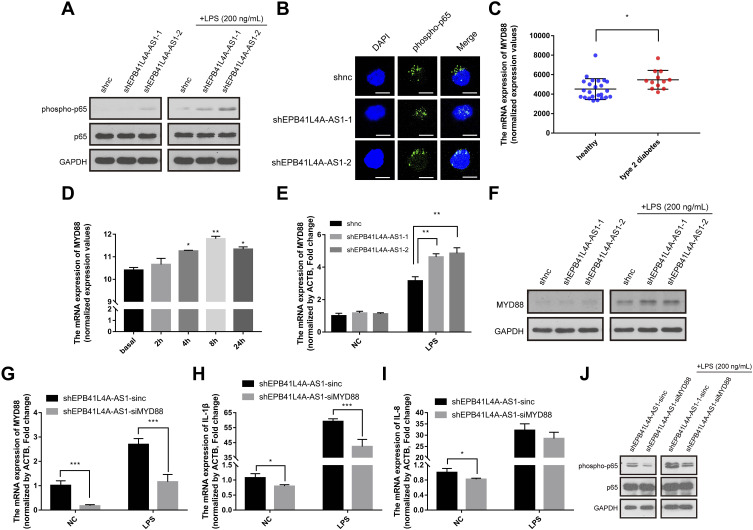

EPB41L4A-AS1 Knockdown Induced MYD88-Mediated NF-κB Activation

As IL-1β and IL-8 are induced by the NF-κB signaling pathway, we hypothesized that EPB41L4A-AS1 may also be involved in the activation of the NF-κB pathway. Activation of the canonical NF-κB signaling pathway involves the phosphorylation of IκB family members, which leads to the release, phosphorylation, and nuclear translocation of p65.15 Thus, by detecting the phosphorylation of p65, we could determine the activation of the NF-κB signaling pathway. To investigate whether EPB41L4A-AS1 was involved in the activation of the NF-κB signaling pathway, we used WB to detect the expression of phospho-p65 in shnc, shEPB41L4A-AS1-1, and shEPB41L4A-AS1-2 cell lines. After 200 ng LPS treatment, the expression of phospho-p65 was higher in shEPB41L4A-AS1-1 and shEPB41L4A-AS1-2 cells than in shnc cells (Figure 5A). Furthermore, previous research showed that after NF-κB activation, phospho-p65 crossed the nuclear membrane and relocated in the nucleus.16–18 Therefore, we performed an immunofluorescence experiment to detect the subcellular localization of phospho-p65 in shnc, shEPB41L4A-AS1-1, and shEPB41L4A-AS1-2 cells under 200 ng LPS treatment. After LPS treatment, the fluorescence signals of phospho-p65 were significantly enriched in the nuclei of shEPB41L4A-AS1-1 and shEPB41L4A-AS1-2 cells, but not in those of shnc cells (Figure 5B). Based on the results of the WB and immunofluorescence experiments, we considered that the absence of EPB41L4A-AS1 would improve the activation of the NF-κB pathway under LPS treatment and increase the expression of inflammatory factors.

Figure 5.

EPB41L4A-AS1 knockdown induced MYD88-mediated activation of the NF-κB pathway. (A) Expression of phospho-p65 and p65 in shnc, shEPB41L4A-AS1-1, and shEPB41L4A-AS1-2 cells without LPS treatment and with 200 ng/mL LPS treatment. (B) Immunofluorescence localization of phospho-p65 in shnc, shEPB41L4A-AS1-1, and shEPB41L4A-AS1-2 cells after 200 ng/mL LPS treatment. Bar represents 20 μm. (C) MYD88 expression in PBMC expression microarray (GDS3874) for T2DM patients. (D) MYD88 expression in expression microarray of human PBMC treated with LPS (GDS2856). (E–F) mRNA and protein expression of MYD88 in shnc, shEPB41L4A-AS1-1, and shEPB41L4A-AS1-2 cells after 200 ng/mL LPS treatment. (G–I) mRNA expression of MYD88, IL-1B, and IL-8 in shEPB41L4A-AS1-sinc and shEPB41L4A-AS1-siMYD88 cells after 200 ng/mL LPS treatment. (J) Expression of phospho-p65 and p65 in shEPB41L4A-AS1-sinc and shEPB41L4A-AS1-siMYD88 cells without LPS treatment and with 200 ng/mL LPS treatment. Data are shown as mean ± SD. *P<0.05, **P<0.01, ***P<0.001; Student’s t-test.

In order to clarify the key factors involved in the activation of NF-κB by EPB41L4A-AS1 knockdown, we analyzed a PBMC expression microarray (GDS3874) of T2DM patients. The expression of MYD88 in the PBMC of T2DM patients was significantly higher compared with that in PBMC of healthy individuals (Figure 5C). Moreover, in another expression microarray from the GEO database (GDS2856), MYD88 was significantly upregulated in PBMC after 4 h, 8 h, and 24 h LPS treatment (Figure 5D). Then, using qRT-PCR and WB, we examined the expression of MYD88 in shnc, shEPB41L4A-AS1-1, and shEPB41L4A-AS1-2 cells after LPS treatment at both the transcription and protein levels. MYD88 expression levels were higher in shEPB41L4A-AS1-1 and shEPB41L4A-AS1-2 cells compared with those in shnc cells (Figure 5E and F). To further clarify that the activation of the NF-κB pathway induced by EPB41L4A-AS1 knockdown was mediated by MYD88, we knocked down MYD88 in the EPB41L4A-AS1 knockdown cells and detected NF-κB activity and the expression of inflammatory factors. Knocking down MYD88 in shEPB41L4A-AS1 cells reduced the expression of inflammatory factors IL-1B and IL-8 (Figure 5G and I). The WB results also showed that knocking down MYD88 in shEPB41L4A-AS1 cells resulted in lower NF-κB activity (Figure 5J).

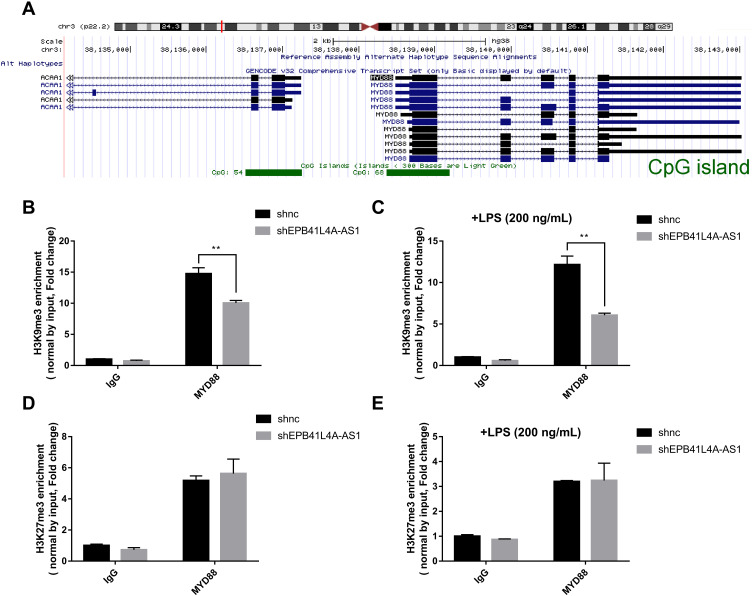

EPB41L4A-AS1 Knockdown Promoted the Upregulation of MYD88 by Enhancing the Enrichment of H3K9me3 in the MYD88 Promoter

The regulation of histone modification is one of the most common methods by which lncRNAs regulate the transcription of downstream genes. In order to further investigate whether EPB41L4A-AS1 regulated MYD88 transcription by regulating the histone modification of MYD88, we analyzed the ENCODE database and found CpG islands in the MYD88 promoter region (Figure 6A). Then, we performed ChIP assays to analyze the enrichment of H3K9me3 and H3K27me3 in the MYD88 promoter. Compared with shnc cells, the knockdown of EPB41L4A-AS1 significantly reduced the enrichment of H3K9me3 in the promoter region of MYD88 (Figure 6B). Under 200 ng LPS treatment, EPB41L4A-AS1 knockdown resulted in a greater reduction of H3K9me3 in the promoter region of MYD88 (Figure 6C). However, knockdown of EPB41L4A-AS1 had almost no effect on the enrichment of H3K27me3 in the promoter region of MYD88 (Figure 6D and E). Therefore, we concluded that EPB41L4A-AS1 knockdown promoted the expression of MYD88 by reducing the enrichment of H3K9me3 in the promoter region of MYD88.

Figure 6.

EPB41L4A-AS1 knockdown enhanced enrichment of H3K9me3 in the promoter of MYD88. (A) Location of CpG island in the MYD88 promoter region, from ENCODE database. (B) ChIP analysis of H3K9me3 enrichment in the promoter of MYD88 without LPS treatment (n=3). (C) ChIP analysis of H3K9me3 enrichment in the promoter of MYD88 with 200 ng/mL LPS treatment (n=3). (D) ChIP analysis of H3K27me3 enrichment in the promoter of MYD88 without LPS treatment (n=3). (E) ChIP analysis of H3K27me3 enrichment in the promoter of MYD88 with 200 ng/mL LPS treatment (n=3). Data are shown as mean ± SD. **P<0.01; Student’s t-test.

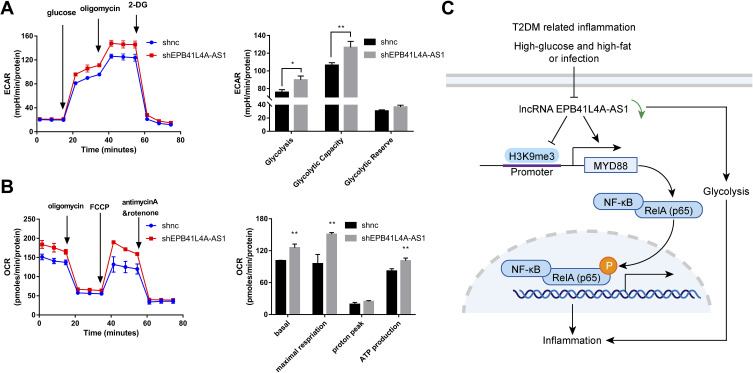

EPB41L4A-AS1 Regulated Glycolysis and Mitochondrial Stress

It has been reported that glucose metabolism can participate in cellular immune responses.19 To investigate whether EPB41L4A-AS1 participated the regulation of glycolysis and mitochondrial stress, we detected physiological indicators of aerobic glycolysis and mitochondrial stress in shnc and shEPB41L4A-AS1 cells, including ECAR and OCR. The results indicated that EPB41L4A-AS1 knockdown promoted glycolysis and enhanced glycolysis capacity (Figure 7A). In addition, the absence of EPB41L4AAS1 significantly increased OCR and enhanced mitochondrial respiration (Figure 7B). Similar results have been reported in previous studies in this laboratory.13,14

Figure 7.

EPB41L4A-AS1 knockdown increased glycolysis and mitochondrial stress. (A) ECAR in shnc and shEPB41L4A-AS1 cells (n=3). (B) OCR in shnc and shEPB41L4A-AS1 cells (n=3). (C) Schematic model of MYD88-mediated activation of the NF-κB pathway by EPB41L4A-AS1 in T2DM-related inflammation. Data are shown as mean ± SD. *P<0.05, **P<0.01; Student’s t-test.

Discussion

The NF-κB transcription factor family plays an important part in the regulation of the inflammatory response process. NF-κB family members regulate a wide range of inflammatory genes and participate in inflammatory regulation. In canonical signaling pathways, intracellular signal transduction is cascade activated; NF‑κB is phosphorylated, which eventually leads to its nuclear translocation. Research has consistently demonstrated that many lncRNAs can regulate the inflammatory response by regulating the NF-κB pathway. In acute spinal cord injury, expression of lncRNA metastasis-associated lung adenocarcinoma transcript 1 was significantly increased; this promoted activation of the NF‑κB signaling pathway by downregulating miR-199b and resulted in the accumulation of inflammatory cytokines including TNF-α and IL-1β.20 In cardiomyocytes of mice with sepsis, increased expression of lncRNA HOTAIR promoted phosphorylation of the NF-κB p65 subunit and activated the NF-κB pathway, thereby stimulating the release of the inflammatory factor TNF-α.21

In this study, the role and regulatory mechanism of lncRNA EPB41L4A-AS1 in the inflammatory process of diabetes were revealed. First, using the GEO database, analysis of PBMC of T2DM patients and PBMC stimulated by LPS showed that EPB41L4A-AS1 was negatively correlated with inflammatory factors (Figures 1 and 2). Hyperglycemia and hyperlipidemia, as well as a chronic inflammatory response, are the main characteristics of T2DM. Ordinarily, HG plus PA medium is used to simulate the diabetic environment, and LPS is used to simulate the T2DM-related inflammatory response.22–25 We found that at the cellular level, high-glucose and high-fat (PA) conditions and inflammatory (LPS) stimulation showed similar effects, that is, a decrease in the expression of EPB41L4A-AS1, which promoted the expression of IL-1β and IL-8. In EPB41L4A-AS1-knockdown cell lines, at both transcription and post-transcription levels, inflammatory stimulation significantly induced the expression of inflammatory factors. Owing to the absence of EPB41L4A-AS1 expression, the increasing amplitude of inflammatory factors expression in EPB41L4A-AS1-knockdown cell lines was significantly higher than in control shnc cells. Moreover, we did not detect IL-1β protein expression in the media of these cells. By combining analysis of protein structures with other research, we found that IL-1α and IL-1β could not be secreted into the media owing to the lack of signaling peptides.23

Previous studies have shown that MYD88 can be activated not only by expression of inflammatory factors such as IL-1β but also by LPS induction; furthermore, this activation could mediate activation of the NF-κB pathway via TRAF6, IRAK1, and IRAK2 and influence the immune response.26–28 Studies have shown that lncRNA AGAP2-AS1 enhances the enrichment of H3K27ac in the promoter region of MYD88, which leads to the upregulation of MYD88 and eventually activates the NF-κB pathway.29 Other studies have shown that E3 ubiquitin ligase Nrdp1 binds to polyubiquitinated MYD88, leading to MYD88 degradation, which results in inhibition of the activation of the NF-κB pathway.30 In this research, in knockdown cell lines under LPS treatment, the absence of EPB41L4A-AS1 expression led to activation of the NF-κB pathway, mediated by high expression of MYD88. Our results suggest that low expression of EPB41L4A-AS1 promoted the expression of MYD88 by reducing the enrichment of H3K9me3 in the MYD88 promoter region and subsequently promoting activation of the NF-κB pathway.

It is well known that when cellular immunity is activated, glucose metabolism will be enhanced.31 At the same time, energy production by oxidative phosphorylation is converted to aerobic glycolysis to maintain inflammation.32 At the metabolic level, we found that EPB41L4A-AS1 knockdown enhanced glycolysis metabolism and mitochondrial stress (Figure 7). Our previous research demonstrated that EPB41L4A-AS1 could regulate cellular metabolic reprogramming in tumors and early RM.13,14 In tumor cells, EPB41L4A-AS1 was regulated by p53 and participated in p53-mediated tumor metabolic reprogramming. Knockdown of p53 could reduce the expression of EPB41L4A-AS1, which in turn improved glycolysis and glutamine metabolism. Moreover, inhibition of the expression of EPB41L4A-AS1 triggered the Warburg effect.13 Research on RM has consistently shown that overexpression of EPB41L4A-AS1 in placental trophoblast cells inhibits glycolysis but increases the dependence of mitochondrial metabolism on fatty acid oxidation, thereby inhibiting the Warburg effect, which is necessary for the rapid growth of placental villus, and eventually leading to miscarriage.14

Conclusions

In summary, in the GEO database, the expression of EPB41L4A-AS1 was decreased in T2DM-related inflammation and showed negative correlations with the expression of inflammatory factors. Our cell experiments had similar results. We further found that EPB41L4A-AS1 knockdown increased expression of inflammatory factors under both LPS treatment and HG and high-fat conditions. Finally, we demonstrated that the absence of EPB41L4A-AS1 expression, on the one hand, activated the MYD88-dependent NF-κB pathway by reducing the enrichment of H3K9me3 in the promoter region of MYD88, and, on the other hand, increased the level of glycolysis and ultimately enhanced the inflammatory response (Figure 7C). The following conclusions can be drawn from the present study. The decreased expression of EPB41L4A-AS1 in PBMC induced by HG and high-fat conditions or by LPS stimulation may be used as an indicator of chronic inflammation in T2DM patients; it also suggests the existence of possible diabetic vascular complications. Moreover, these findings suggest that in T2DM treatment, therapeutic drugs that function as both hypoglycemic and anti-inflammatory agents, such as canagliflozin, should be taken into consideration.

Acknowledgments

This research was funded by the international cooperation fund of Shenzhen (GJHZ20180929162002061) and the National Natural Science Foundation of Young Scientists of China (31900540).

Statement of Ethics

The research was approved by the Bioethics Committee of Shenzhen International Graduate School of Tsinghua University (No. 2020-41). All procedures performed in this study were ethically in accordance with the World Medical Association Declaration of Helsinki.

Disclosure

The authors report no conflicts of interest in this work.

References

- 1.Wu Y, Ding Y, Tanaka Y, et al. Risk factors contributing to type 2 diabetes and recent advances in the treatment and prevention. Int J Med Sci. 2014;11(11):1185–1200. doi: 10.7150/ijms.10001 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Prattichizzo F, De Nigris V, Spiga R, et al. Inflammageing and metaflammation: the yin and yang of type 2 diabetes. Ageing Res Rev. 2018;41:1–17. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Donath MY, Shoelson SE. Type 2 diabetes as an inflammatory disease. Nat Rev Immunol. 2011;11:98–107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Pedersen BK. Anti‐inflammatory effects of exercise: role in diabetes and cardiovascular disease. Eur J Clin Invest. 2017;47:600–611. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Petrie JR, Guzik TJ, Touyz RM. Diabetes, hypertension, and cardiovascular disease: clinical insights and vascular mechanisms. Can J Cardiol. 2018;34:575–584. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Zhang X, Hong R, Chen W, et al. The role of long noncoding RNA in major human disease. Bioorg Chem. 2019;103214. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.de Oliveira JC, Oliveira LC, Mathias C, et al. Long non‐coding RNAs in cancer: another layer of complexity. J Gene Med. 2019;21:e3065. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Li Y, Egranov SD, Yang L, et al. Molecular mechanisms of long noncoding RNAs‐mediated cancer metastasis. Gene Chromosome Canc. 2019;58:200–207. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Marchese FP, Raimondi I, Huarte M. The multidimensional mechanisms of long noncoding RNA function. Genome Biol. 2017;18:206. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Suwal A, Hao J, Liu X, et al. NONRATT021972 long-noncoding RNA: A promising lncRNA in diabetes-related diseases. Int J Med Sci. 2019;16(6):902–908. doi: 10.7150/ijms.34200 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Shi Y, Patel NA, Cai J. Discovery of a macrocyclic γ-AApeptide binding to lncRNA GAS5 and its therapeutic implication in Type 2 diabetes. Future Med Chem. 2019;11(17):1756–8927. doi: 10.4155/fmc-2019-0148 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Yabuta N, Onda H, Watanabe M, et al. Isolation and characterization of the TIGA genes, whose transcripts are induced by growth arrest. Nucleic Acids Res. 2006;34(17):4878–4892. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkl651 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Liao M, Liao W, Xu N, et al. LncRNA EPB41L4A-AS1 regulates glycolysis and glutaminolysis by mediating nucleolar translocation of HDAC2. EBioMedicine. 2019;41:200–213. doi: 10.1016/j.ebiom.2019.01.035 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Zhu Y, Liu Q, Liao M, et al. Overexpression of lncRNA EPB41L4A-AS1 Induces Metabolic Reprogramming in Trophoblast Cells and Placenta Tissue of Miscarriage. Mol Ther-Nucl Acids. 2019;18:518–532. doi: 10.1016/j.omtn.2019.09.017 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Sun S. The non-canonical NF-κB pathway in immunity and inflammation. Nat Rev Immunol. 2017;17:545–558. doi: 10.1038/nri.2017.52 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Zhou W, Chen X, Hu Q, et al. Galectin-3 activates TLR4/NF-κB signaling to promote lung adenocarcinoma cell proliferation through activating lncRNA-NEAT1 expression. BMC Cancer. 2018;18(1):580. doi: 10.1186/s12885-018-4461-z [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Roy A, Ahir M, Bhattacharya S, et al. Induction of mitochondrial apoptotic pathway in triple negative breast carcinoma cells by methylglyoxal via generation of reactive oxygen species. Mol Carcinog. 2017;56:2086–2103. doi: 10.1002/mc.22665 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Li S, Cui K, Fu J, et al. EPO promotes axonal sprouting via upregulating GDF10. Neurosci Lett. 2019;711:134412. doi: 10.1016/j.neulet.2019.134412 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Wang N, Li J, Zhao T, et al. FGF-21 plays a crucial role in the glucose uptake of activated monocytes. Inflammation. 2019;16(1):73–80. doi: 10.1007/s10753-017-0665-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Zhou H, Wang L, Wang D, et al. Long noncoding RNA MALAT1 contributes to inflammatory response of microglia following spinal cord injury via the modulation of a miR-199b/IKKβ/NF-κB signaling pathway. Am J Phys Cell Phys. 2018;315(1):C52–C61. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.00278.2017 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Wu H, Liu J, Li W, et al. LncRNA-HOTAIR promotes TNF-α production in cardiomyocytes of LPS-induced sepsis mice by activating NF-κB pathway. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2016;471(1):240–246. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2016.01.117 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Chokpaisarn J, Urao N, Voravuthikunchai SP, et al. Quercus infectoria inhibits Set7/NF-κB inflammatory pathway in macrophages exposed to a diabetic environment. Cytokine. 2017;17:29–36. doi: 10.1016/j.cyto.2017.04.005 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Bhatta A, Yao L, Xu Z, et al. Obesity-induced vascular dysfunction and arterial stiffening requires endothelial cell arginase 1. Cardiovasc Res. 2017;113:1664–1676. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Huang S, Rutkowsky JM, Snodgrass RG, et al. Saturated fatty acids activate TLR-mediated proinflammatory signaling pathways. J Lipid Res. 2012;53:2002–2013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Sheedy FJ, Palsson-McDermott E, Hennessy EJ, et al. Negative regulation of TLR4 via targeting of the proinflammatory tumor suppressor PDCD4 by the microRNA miR-21. Nat Immunol. 2010;11:141–147. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Gorina R, Font‐Nieves M, Márquez‐Kisinousky L, et al. Astrocyte TLR4 activation induces a proinflammatory environment through the interplay between MyD88‐dependent NFκB signaling, MAPK, and Jak1/Stat1 pathways. Glia. 2011;59:242–255. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kawai T, Sato S, Ishii KJ, et al. Interferon-α induction through Toll-like receptors involves a direct interaction of IRF7 with MyD88 and TRAF6. Nat Immunol. 2004;5:1061–1068. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Ohnishi H, Tochio H, Kato Z, et al. Structural basis for the multiple interactions of the MyD88 TIR domain in TLR4 signaling. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S As. 2009;106:10260–10265. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Dong H, Wang W, Mo S, et al. SP1-induced lncRNA AGAP2-AS1 expression promotes chemoresistance of breast cancer by epigenetic regulation of MyD88. J Exp Clin Cancer Res. 2018;37:1–15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar] [Retracted]

- 30.Wang C, Chen T, Zhang J, et al. The E3 ubiquitin ligase Nrdp1ʹpreferentially’promotes TLR-mediated production of type I interferon. Nat Immunol. 2009;10:744–752. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Palsson‐McDermott EM, O’neill LA. The Warburg effect then and now: from cancer to inflammatory diseases. Bioessays. 2013;35:965–973. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Maratou E, Dimitriadis G, Kollias A, et al. Glucose transporter expression on the plasma membrane of resting and activated white blood cells. Eur J Clin Invest. 2007;37:282–290. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]