Summary

The availability of a safe and effective vaccine would be the eventual measure to deal with severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus-2 (SARS-CoV-2) threat. Here, we have assessed the immunogenicity and protective efficacy of inactivated SARS-CoV-2 vaccine candidates BBV152A, BBV152B, and BBV152C in Syrian hamsters. Three dose vaccination regimes with vaccine candidates induced significant titers of SARS-CoV-2-specific IgG and neutralizing antibodies. BBV152A and BBV152B vaccine candidates remarkably generated a quick and robust immune response. Post-SARS-CoV-2 infection, vaccinated hamsters did not show any histopathological changes in the lungs. The protection of the hamster was evident by the rapid clearance of the virus from lower respiratory tract, reduced virus load in upper respiratory tract, absence of lung pathology, and robust humoral immune response. These findings confirm the immunogenic potential of the vaccine candidates and further protection of hamsters challenged with SARS-CoV-2. Of the three candidates, BBV152A showed the better response.

Subject areas: Biological Sciences, Immunity, Immunology, Viral Microbiology, Virology

Graphical Abstract

Highlights

-

•

Vaccine candidates, BBV152 induced potent humoral immune response in Syrian hamsters

-

•

Early viral clearance from lower respiratory tract in vaccinated hamsters

-

•

BBV152 vaccine candidates protected Syrian hamsters from pneumonia

Biological Sciences; Immunity; Immunology; Viral Microbiology; Virology

Introduction

Since the first report in December 2019, severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus-2 (SARS-CoV-2) has spread at an alarming rate. It has infected more than 55.3 million people with about 1.3 million cases succumbed to the disease across 220 countries and territories around the world until 18 November 2020 (World Health Organization, 2020a). Globally, scientific communities are actively engaged and trying to develop suitable vaccine candidates and specific antiviral therapies against this virus. Vaccination is the most significant pharmaceutical intervention for the prevention of any infectious disease impacting the health of communities worldwide. Accelerated efforts are being taken for the development of a safe and effective vaccine worldwide which is evident by the number of vaccine candidates under preclinical and clinical evaluation. According to the World Health Organization draft landscape document on COVID-19 candidate vaccines published on 3rd November 2020, 47 vaccine candidates are under clinical and 155 under preclinical studies (World Health Organization, 2020b).

SARS-CoV-2 is an enveloped, single-stranded, positive-sense RNA virus that belongs to the genus Betacoronavirus of the family Coronaviridae. There are other coronaviruses known to infect humans like human coronavirus (HCoV) 229E and NL63 (Alphacoronavirus), HCoV-OC43, HKU1, SARS-CoV, and Middle East respiratory syndrome coronavirus (MERS-CoV) (Betacoronavirus). Although the reported mortality of COVID-19 is less compared to the SARS and MERS, the rate of transmission is much higher than these viruses (Wilder-Smith, et al., 2020). The disease has an overall case fatality rate of 0.5%–2.8% with higher rates i.e. 3.7–14.8% in elderly patients (The Center for Evidence-Based Medicine, 2020).

The origin of SARS-CoV-2 seems to be from bat, while the role of intermediate host is still debatable (Docea, et al., 2020). SARS-CoV-2 is usually transmitted through droplets and contact with contaminated surfaces (Phan et al., 2020). Adults and elderly individuals with history of respiratory diseases, metabolic diseases and weaker immune system are more prone to the disease (Tsatsakis, et al., 2020). Additionally, there are many factors like environmental factors, societal customs, and personal hygiene which can aid in the spread of SARS-CoV-2 (Goumenou, et al., 2020). On an average, symptomatic cases can transmit the infection to three people. However, the virus can be also be transmitted during the early phase of illness when the patients are asymptomatic (Li, et al., 2020).

The incubation period of COVID-19 ranges from 2 to 14 days with a median period of 5 days. It is characterized by mild to severe illness with signs and symptoms such as fever, dry cough, vomiting, diarrhea, myalgia, dyspnea, and pulmonary infiltrates (Tsatsakis, et al., 2020). There are no approved antiviral drugs available for the treatment of COVID-19. The mild cases are treated symptomatically, and severe cases are managed with intensive care interventions. Recently, the use of remdesivir for the treatment of COVID-19 cases has been authorized by the US Food and drug organization under Emergency Use Authorization. However, it is yet to be given not complete approval (Islam, et al., 2020). Considering the pandemic's nature and dreadful scenario of COVID-19, vaccines will be the most appropriate and effective intervention for controlling the rapid spread of this disease.

Currently along with the conventional vaccine development platforms, advanced technologies are being used for the development of vaccines against SARS-CoV-2 like messenger RNA, DNA, viral vectors, recombinant subunit proteins, virus-like particles, etc (Pandey et al., 2020). Despite the advances in vaccine design technologies, the development of an inactivated vaccine remains the most simple and relatively less expensive approach to produce a safe and effective vaccine. Inactivated vaccines have been used effectively to curb many infectious diseases in the past (Sanders et al., 2015). Recently, two inactivated SARS-CoV-2 vaccine candidates have shown promising results in preclinical trials (Gao et al., 2020; Wang et al., 2020).

Multiple animal models have been used to evaluate the efficacy of SARS-CoV-2 vaccine candidates. Syrian hamster (Mesocricetus auratus) is one such model which has been used in diverse research studies on SARS-CoV-2 and seems to be the appropriate model as it mimics the human disease in comparison to other animals (Mohandas et al., 2020; Luan et al., 2020; Chan et al., 2020; Imai et al., 2020; Wang et al., 2019; Sia et al., 2020). Moreover, high binding affinity of SARS-CoV-2 spike glycoprotein receptor-binding domain to hamster ACE2 has been predicted with in silico structural analysis (Chan et al., 2020). The study on the SARS-CoV-2 pathogenesis in hamsters demonstrated the pulmonary pathology and high lung viral load during the first week of infection (Chan et al., 2020). Similarly, our study among various small laboratory animal models demonstrated effective SARS-CoV-2 replication in the upper and lower respiratory tract of hamsters compared to mice (Mohandas et al., 2020). Besides this, Syrian hamsters have been successfully used to evaluate medical countermeasures for SARS-CoV-2 by multiple research groups (Luan et al., 2020; Chan et al., 2020; Imai et al., 2020; Rogers et al., 2020; Tostanoski et al., 2020).

We have developed three whole virion inactivated vaccine candidates BBV152A [3μg + Aluminum hydroxide (Algel)-Imidazoquinoline (IMDG)], BBV152B (6μg + Algel-IMDG) and BBV152C (6μg + Algel) using β-propiolactone inactivation method. The vaccine candidates along with Algel adjuvant alone or with Algel chemisorbed with IMDG was found to be immunogenic and safe in the preclinical studies on laboratory mice, rats, and rabbits (Ganneru et al., 2020). Here, we report the immunization of Syrian hamsters with these vaccine candidates and evaluation of protective efficacy against SARS-CoV-2 by carrying out virus challenge experiment in immunized hamsters.

Results

Optimization of SARS-CoV-2 challenge dose in Syrian hamsters

For assessment of the SARS-CoV-2 challenge dose after immunization, a 10-fold serial dilutions of 105.5 median tissue culture infectious dose (TCID50) were used. One hundred microliter (μL) from each of the 5 dilutions (105.5, 104.5,103.5, 102.5, and 101.5) was inoculated intranasally in 5 groups of 6 hamsters each. On 3 day post-infection (DPI), 3 hamsters each from all the 5 groups were sacrificed and the lung viral titers were measured. Virus load was found to be similar in all the hamsters by real-time Reverse transcription-Polymerase Chain Reaction (RT-PCR) irrespective of the virus dilutions inoculated. Further to confirm this finding, virus titration was performed on the same lung samples and TCID50 titer ranging between 105.48 and 105.58 was observed in all samples on 3 DPI (Figure S1). Similarly on day 14, the remaining hamsters were sacrificed and lung samples were found to show a titer of 102.5 TCID50/ml in all the animals, indicating that viral inoculums could induce disease in all hamsters (Figure S1). On histopathological analysis, lungs samples of the hamsters inoculated with the 105.5 TCID50 and 104.5 TCID50 dilutions collected on 3DPI showed mild inflammatory changes indicating beginning of pneumonia, whereas other groups showed minimal or no changes. On 14 DPI, the lung pathological changes were found minimal in all groups indicating recovery from infection. Even though the lung viral titers in all groups were similar irrespective of the dose of virus inoculums, the lung pathological changes indicated the rapid induction of pneumonic changes in 105.5 and 104.5 dilutions. Hence, a virus dilution dose of 105.5 TCID50 was used for virus challenge.

Clinical observations during BBV152A, BBV152B, and BBV152C immunization period and after SARS-CoV-2 challenge

We immunized four groups of 6–8-week-old Syrian hamsters (9 hamsters in each group), with phosphate buffered saline (group I), BBV152C (group II), BBV152A (group III), and BBV152B (group IV) (Figure 1) with two doses on day 0 and 14. All the hamsters received one more booster dose on day 35. Rectal temperature remained within the normal range, and no clinical signs were observed in all the groups throughout the immunization period. The body weight increased until 7 weeks post-immunization (Figure 2A) but following SARS-CoV-2 infection on day 50, a decrease in body weight was observed in all the groups (Figure 2B). However, the percentage decrease in vaccinated groups were lesser compared to the group I. The decrease in body weight of group III hamsters was less as compared to other groups (Figure 2B).

Figure 1.

Schematic presentation of experiments in hamsters

Three doses of placebo were administered to the first group of the animals which were controls in the study. Three different inactivated SARS-CoV-2 vaccine formulations (2 doses + boost) were administered to the three groups of animals. All the animals were challenged at 15 days after the third dose. Samples were collected at different time points of immunization period and post-infection as indicated in the figure. Necropsy was performed for three hamsters from each group at 3, 7, and 15 DPI.

Figure 2.

Percent body weight gain/loss in hamsters

(A) Percentage of body weight gain in hamsters during the immunization period.

(B) Percent difference in body weight in hamsters after SARS-CoV-2 challenge. Mean along with standard deviation (SD) is depicted in the scatterplot. The statistical significance was assessed using the Kruskal-Wallis test followed by the two-tailed Mann-Whitney test between the two groups; p values less than 0.05 were considered to be statistically significant.

Inactivated whole virion vaccine candidates BBV152A, BBV152B, and BBV152C induced specific IgG/neutralizing antibody

Anti-SARS-CoV-2 IgG antibody response was detected by third week in 8 of 9 hamsters of group IV with an average optical density (OD) of 0.62, 8 of 9 hamsters in group III with an average OD of 0.42 and in 2 of 9 hamsters (average OD = 0.285) of group II. On day 48, IgG antibody response was found to be increasing in the vaccinated groups with an average OD of 1.32 in group IV (9 of 9 hamsters), 1.2 in group III (9 of 9 hamsters) and 0.55 in group II (9 of 9 hamsters) (Figures 3A and 3C). All the animals in group I remained negative for IgG antibody during immunization period, whereas after virus challenge, 2 of 3 hamsters showed IgG positivity by 7 DPI and 3 of 3 by 14 DPI (average OD = 0.29) in the group I (Figure 3B). In the vaccinated groups, an increasing trend with an average OD of 0.84, 0.97, and 0.91 was observed on days 3, 7, and 15 DPI, respectively (Figure 3D). No significant difference was observed in the IgG antibody response post-infection in group III and IV.

Figure 3.

Humoral response in vaccinated animals

(A) IgG antibody response for all groups of animals observed on 12, 21, and 48 days.

(B) IgG antibody response at post-infection (3, 7, and 15 DPI) for all groups of animals.

(C) Comparison of IgG antibody titers between groups on 12, 21, and 48 days.

(D) Comparison of IgG antibody titers between groups after virus challenge at 3, 7, and 15 DPI.

(E). Comparison of IgG2 antibody titers between groups during immunization period at 21 and 48 days and post virus challenge at 3,7, and 15 DPI.

(F and G) (F). Comparison of NAb titers response during a three-dose vaccine regime for all groups of animals observed on 12, 21, and 48 days (G). Comparison of NAb titers response in SARS-CoV-2 infected animals on 3, 7, and 15 DPI. Mean along with standard deviation (SD) is depicted in the scatterplot. The statistical significance was assessed using the Kruskal-Wallis test followed by the two-tailed Mann-Whitney test between the two groups; p values less than 0.05 were considered to be statistically significant. The dotted lines indicate the limit of detection of the assay.

IgG antibody response in vaccinated hamsters was further characterized to determine the IgG subclass profiles. On sub-typing, IgG2 was detected in all the IgG antibody positive samples, whereas it was negative for IgG1 during immunization and post-infection phase (Figure 3E). All three formulations of vaccine candidates significantly induced IgG2 with an increasing trend post-infection.

Neutralizing antibody (NAb) started appearing in the immunized groups at third week of immunization and increased till seventh week with highest titer (mean = 28,810) in group III (Figure 3F). After virus infection, the highest titer of NAb (mean = 85,623) was seen in group III animals on 15 DPI. Group I did not show NAb response during immunization phase and after virus infection till 15 DPI (Figure 3G).

Detection of SARS-CoV-2 genomic RNA (gRNA) in swabs/ organ samples after virus challenge in immunized animals

SARS-CoV-2 viral genomic RNA (gRNA) copy number in throat swabs (TSs) of group I were significantly higher than other groups on 3, 5, and 7 DPI (Figure 4A). The viral gRNA in group I persisted till 10 DPI, whereas it was cleared in all the vaccinated groups by 7 DPI. Higher copy numbers of viral gRNA were detected in the nasal washings of group I in comparison to immunized animals (Figure 4B).

Figure 4.

Log10 plot for the genomic viral RNA detection in throat swab and nasal wash after virus challenge

Genomic viral RNA load in (A) Throat Swab collected at 3, 5, 7, 10, and 15 DPI for the all groups (B) Nasal wash genomic viral RNA at 3, 7, and 15 DPI for the all groups. Mean along with standard deviation (SD) is depicted in the scatterplot. The statistical significance was assessed using the Kruskal-Wallis test followed by the two-tailed Mann-Whitney test between the two groups; p values less than 0.05 were considered to be statistically significant. The dotted lines indicate the limit of detection of the assay.

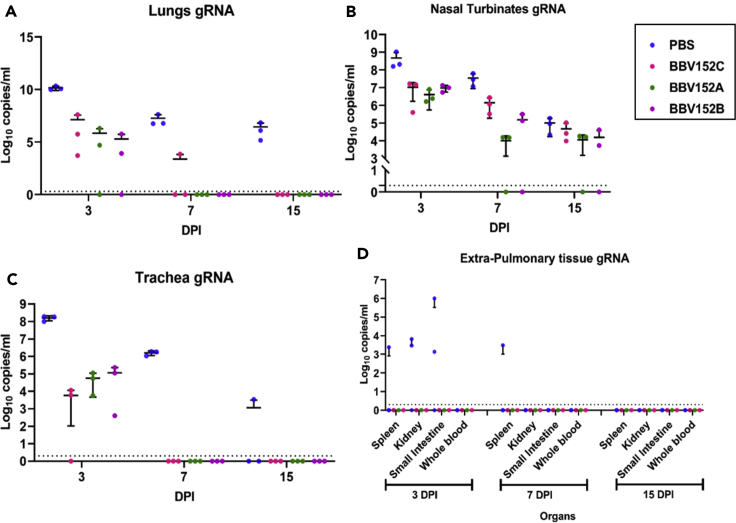

Lungs (Figure 5A), nasal turbinates (Figure 5B), and trachea (Figure 5C) of group I showed higher viral gRNA copy number compared to immunized groups on 3 and 7 DPI. Trachea was cleared of viral gRNA by 7 DPI in all the vaccinated groups. Complete gRNA clearance was observed from lungs of group III and IV on 7 DPI and from group II by 15 DPI. Nasal turbinates viral gRNA persisted in all the groups till 15 DPI but with lower copy numbers in vaccinated groups compared to group I. No viral subgenomic (sg) RNA was detected in TS, nasal wash, nasal turbinate or trachea of animals of vaccinated groups. However viral sgRNA was detected in lungs (3/3), trachea (1/3), and nasal turbinate (1/3) in group I animals on 3 DPI. The spleen, kidney, and small intestine of hamsters of group I showed viral gRNA positivity on 3 DPI as well (Figure 5D).

Figure 5.

Log10 plot of the genomic viral RNA detection in the respiratory tract and extra pulmonary specimens

Genomic viral RNA load in (A) lung, (B) nasal turbinates, (C) trachea, (D) extra pulmonary organs at 3, 7, and 15 DPI. Mean along with standard deviation (SD) is depicted in the scatterplot. The statistical significance was assessed using the Kruskal-Wallis test followed by the two-tailed Mann-Whitney test between the two groups; p values less than 0.05 were considered to be statistically significant. The dotted lines indicate the limit of detection of the assay.

Virus titration

Lungs and nasal turbinate samples of group I showed an average titer of 106 and 105.5 TCID50/ml, respectively, on 3 DPI. In the vaccinated groups III and IV, nasal turbinates showed an average titer of 105 and 104 TCID50/ml on 3DPI, whereas the lungs titer was found considerably less (102.5TCID50/ml) compared to group I. In contrast, group II did not show live virus titer in any of the specimens on 3, 7, and 15 DPI. The samples of group II animals (n = 3) on 3 and 7 DPI were repeated for virus titration and also attempt was made for virus isolation, but in second passage in Vero CCL81 cells, the viral RNA presence was found negligible in samples showing that virus was not replicating in these samples. On 7 DPI, only nasal turbinates of group I showed virus titer, whereas vaccinated groups were negative. This correlates with the decreasing trend of gRNA and sgRNA in immunized groups after 3 DPI.

Pathological and immuno-histochemical findings in lungs after virus challenge

The lungs of the vaccinated groups appeared normal on 3, 7, and 15 DPI (Figures 6B, 6C, and 6D) grossly, whereas on 7 DPI, the lungs of group I showed diffuse areas of consolidation and congestion (Figure 6A). On histopathological examination, lung sections from group I animals showed congestion, haemorrhages, exudations in the alveoli, mononuclear cell infiltration in the alveolar interstitium, and pneumocyte hyperplasia on 3 and 7 DPI (Figures 6E and 6F). Occasionally, loss of bronchiolar epithelium was also observed. By 15 DPI, fibro-elastic proliferation with collagen deposition at alveolar epithelial lining were observed in the lungs of group I (Figure 6G). Vaccinated group animals did not show any histopathological evidence of pneumonia except few congestive foci on 3 DPI (Figures 6H, 6I, 6J, and S2). The viral antigen could be detected in alveolar type-II pneumocytes and macrophages on 3, 7, and 15 DPI in the lungs of group I animals (Figures 7A, 7B, and 7C), whereas only focal positivity was detected in the vaccinated groups on 3 DPI. On 7 and 15 DPI, viral antigen was not detected in the lung sections of vaccinated hamsters from all the groups on immunohistochemistry (Figures 7D, 7E, 7F, and S3).

Figure 6.

Gross and histopathological observations of lungs in hamsters after virus inoculation

(A–D) (A) Lungs of hamster from group I on 7 DPI showing diffuse areas of consolidation and congestion in the left and right lower lobe with few congestive foci in right upper lobe, scale bar = 0.73cm. Lungs from (B) group II, scale bar = 0.65cm (C) group III, scale bar = 0.73cm and (D) group IV showing normal gross appearance on 7 DPI scale bar = 0.52cm.

(E) Lung tissue from group I on 3 DPI showing acute inflammatory response with diffuse alveolar damage, haemorrhages, inflammatory cell infiltration (black arrow), hyaline membrane formation (white arrow), and accumulation of eosinophilic edematous exudate (star), scale bar = 20μm.

(F) Lung tissue of group I on 7 DPI showing acute interstitial pneumonia with marked alveolar damage, thickening of alveolar and accumulation of mononuclear cells, and macrophages (white arrow), and lysed erythrocytes in the alveolar luminal space (star), scale bar = 20μm.

(G–J) (G) Lung tissue from group I on 15 DPI depicting interstitial pneumonia with marked thickening of alveolar septa with type-II pneumocyte hyperplasia and fibro-elastic proliferation with collagen deposition at alveolar epithelial lining (white arrow), scale bar = 20μm. Lung section from group II showing no evidence of disease (H) on 3 DPI few congestive foci, scale bar = 20μm (I) on 7 DPI, scale bar = 20μm (J) on 15 DPI, scale bar = 20μm.

Figure 7.

Immunohistochemistry findings in lungs of hamsters after virus challenge

Left panel depicts group treated with placebo and the right panel shows vaccinated group II animals. Lung section from group I showing viral antigen (A) on 3 DPI in alveolar type-II pneumocytes (black arrow) and in alveolar macrophages (white arrow), scale bar = 20μm (B) on 7 DPI in alveolar type-II pneumocytes (black arrow), scale bar = 20μm (C) on 15 DPI in type-II alveolar pneumocytes (black arrow), scale bar = 20μm. Lung section from group II showing viral antigen (D) on 3 DPI in alveolar macrophages (black arrow), scale bar = 20μm (E) on 7 DPI in alveolar epithelium and alveolar macrophages, scale bar = 20μm (F) on 15 DPI in the alveolar epithelium and alveolar macrophages, scale bar = 20μm.

Cytokine profile after virus challenge

After challenge with the virus, vaccinated groups did not show any significant elevation of cytokines i.e TNF-α, IL-4, IL-10, IL-6, IFN-γ, and IL-12, whereas in control group increased level of IL-12 was detected on 3 DPI which further reduced on 7 and 15 DPI (Figure S4).

Discussion

Preclinical research in animal models is an important step in evaluating the immunogenicity and protective efficacy of vaccine candidates. Syrian hamster (Mesocricetus auratus) has been used in diverse research studies on SARS-CoV-2 and seems to be the appropriate model as it mimics the clinical signs, antibody response, viral kinetics, and histopathological changes of human disease (Chan et al., 2020; Luan et al., 2020; Mohandas et al., 2020; Imai et al., 2020; Wang et al., 2019). We performed a preliminary dose optimization study in Syrian hamsters for the experiment and observed that the viral RNA load in the lungs samples of infected hamsters did not show any difference with dose administered. Similar findings were reported with experimental inoculation of 103 or 105 TCID50 of SARS-CoV and 105.6 PFU or 103 PFU SARS CoV-2 in Syrian hamsters (Roberts et al., 2005; Imai et al., 2020) indicating the capability of virus to replicate to high titers in pulmonary tract, even at lower doses. We observed replication even at still lower doses of 101.5 and 102.5 TCID50 than earlier reported studies.

The safety and immunogenicity profile of the vaccine candidates BBV152A, BBV152B, and BBV152C has been established in mice, rat, and rabbit models (Ganneru et al., 2020). Here, we report the immunogenicity and protective efficacy of these inactivated SARS-CoV-2 vaccine candidates in the hamster model. NAb are considered as a correlate of protection in SARS-CoV-2 infection in humans (Addetia et al., 2020). SARS-CoV-2 vaccination experiments in hamster and rhesus macaque models also indicated the same (Tostanoski et al., 2020; Yu et al., 2020). BBV152 induced SARS-CoV-2-specific IgG or NAbs in hamsters from third week post-immunization similar to the response observed in mice, rats, rabbits, and rhesus macaques (Ganneru et al., 2020; Yadav et al., 2020). In other SARS-CoV-2 inactivated vaccine candidates like PiCoVacc and BBIBP-CorV, studied in non-human primate model, the NAb were observed from first and second week, respectively, with a period of detection till 5 weeks (Gao et al., 2020; Wang et al., 2020). In the BBV152A, BBV152B, and BBV152C vaccinated groups, NAbs showed an increasing trend till 7 weeks and also after SARS-CoV-2 challenge (15 DPI). Although there was no statistically significant difference, group III showed the highest NAb titer after challenge i.e, a 2–3-fold rise compared to pre-challenge. Dose sparing effect of the antigen was evident in the NAb response after challenge by Algel + IMDG group similar to the study reports of Ganneru et al. (2020) in mice. A limitation of this study is that we could not assess the cross-neutralizing ability of this NAb with other related virus like SARS-CoV. Recent studies have reported the existence of broad cross-neutralizing epitopes within lineage B and the cross-neutralizing ability of two SARS-CoV NAb to neutralize SARS-CoV-2 (Lv et al., 2020).

We identified the IgG subclasses induced by BBV152A, BBV152B, and BBV152C and found a predominant IgG2 response with an increasing trend during the immunization and post challenge phase in hamsters. Studies in mice model with the same vaccine candidate have shown a distinct Th1 biased response with a higher average ratio of IgG2a/IgG1 especially with the Algel + IMDG group (Ganneru et al., 2020).

Compared to the placebo group, rapid virus clearance was observed in the vaccinated groups from the respiratory tract except for nasal turbinates. We observed the viral gRNA persistence in the nasal turbinates till day 15 in all groups, but the gRNA copy number was lower in vaccinated groups compared to placebo. Many SARS-CoV-2 vaccines in development also reported the absence or partial clearance of virus from the upper respiratory tract (van Doremalen et al., 2020; Yu et al., 2020). Upper and lower respiratory tract protection is thought to be mainly mediated by the secretory IgA and IgG, respectively (Reynolds, 1988; Holmgren and Czerkinsky, 2005). Intramuscular vaccinations generally lead to antigen-specific systemic humoral and cell-mediated immune responses, but their ability to induce mucosal immunity is poor (Krammer, 2020). There are also reports of parenteral vaccine-induced mucosal responses in humans and experimental animal models (Clements and Freytag, 2016). Mucosal immune responses were not studied in the current experiment.

The inactivated vaccine candidates BBV152A, BBV152B, and BBV152C studies in rhesus macaque showed complete clearance of virus by 7 DPI in respiratory organs (Yadav et al., 2020). Dose-related difference in viral clearance was observed in other inactivated vaccine candidates like PiCOvacc and BBIBP-CorV, where lower dose groups were found less effective in clearance (Gao et al., 2020; Wang et al., 2020). Gross and histopathological examination of the lungs of the placebo group had evidence of interstitial pneumonia in the placebo group on 3 and 7 DPI. However, vaccinated groups had no evidence of gross and histopathological changes indicating the protective efficacy of these inactivated vaccine candidates. Lower viral load, absence of lung pathology, and high titers of neutralizing antibodies post-infection demonstrate the protective efficacy of BBV152A, BBV152B, and BBV152C in immunized hamsters, and of these three candidates, BBV152A showed the better response.

Limitations of the study

The cross-neutralizing potential of the NAb with other SARS CoV-2 clades, longevity of the antibody response, and the cell-mediated immune response elicited by vaccine candidates needs to be explored further.

Resource availability

Lead contact

Further information and requests for resources and reagents should be directed to the lead contact, Dr. Pragya D Yadav, Scientist ‘E’ and group Leader, Maximum Containment Facility, Indian Council of Medical Research-National Institute of Virology, Pune at (hellopragya22@gmail.com).

Materials availability

This study did not generate new unique reagents.

Data and code availability

The published article includes all data sets generated or analyzed during this study.

Methods

All methods can be found in the accompanying Transparent Methods supplemental file.

Acknowledgments

The authors acknowledge the financial support provided by the Indian Council of Medical Research, New Delhi, at ICMR-National Institute of Virology, Pune. We acknowledge the support received from laboratory team which includes Dr. Himanshu Kaushal, Deepak Mali, Rashmi Gunjikar, Rajen Lakra, Shreekant Baradkar, Pranita Gawande, Ganesh Chopade, Manjunath Holleppanavar, Ratan More, Darpan Phagiwala, Chetan Patil, Sanjay Thorat, Ratan More, Madhav Acharya, Malvika Salave, Ashwini Baghmare, Ciyona, Sapna Gawande, Nitin Deshpande, Poonam Bodke, Deepika Chawdhary, Mayur Mohite, Vishal Gaikwad and Nandkumar Sharma of ICMR-National Institute of Virology, Pune, India. We acknowledge the excellent support of Dr. Sapan Kumar Behra, Dr. Shashi Kanth Muni and Dr. Brunda Ganneru from Bharat Biotech International Limited, Genome Valley, Hyderabad, Dr. Rajaram Ravikrishnan, RCC Laboratories India Private Limited, Hyderabad, and Dr B. Dinesh Kumar, Scientist G, ICMR-National Institute of Nutrition, Hyderabad, Telangana, India.

Author contributions

PDY, SM, KM, PA, NG, and BB conceived and designed the study. KME, RE, VKS, and SDP performed vaccine design and production. PDY and SM performed the planning of animal experiments. SM, PDY, MK, AK, and CM performed the animal experimentation. PDY, AS, GS, GD, DN, and DYP performed the laboratory work planning and data analysis. GD, SP, RJ, TM, SS, and PS performed sample processing in the laboratory. PDY, SM, DN, AS, and DYP have drafted the manuscript. PDY, SM, AS, DYP, KM, PA, NG, SP, and BB substantively revised it. All authors reviewed the manuscript and agree to its contents.

Declaration of interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Published: February 19, 2021

Footnotes

Supplemental information can be found online at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.isci.2021.102054.

Supplemental information

References

- Addetia A., Crawford K.H., Dingens A., Zhu H., Roychoudhury P., Huang M.L., Jerome K.R., Bloom J.D., Greninger A.L. Neutralizing antibodies correlate with protection from SARS-CoV-2 in humans during a fishery vessel outbreak with a high attack rate. J. Clin. Microbiol. 2020;58:e02107–e02120. doi: 10.1128/JCM.02107-20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chan J.F., Zhang A.J., Yuan S., Poon V.K., Chan C.C., Lee A.C., Chan W.M., Fan Z., Tsoi H.W., Wen L., Liang R. Simulation of the clinical and pathological manifestations of Coronavirus Disease 2019 (COVID-19) in golden Syrian hamster model: implications for disease pathogenesis and transmissibility. Clin. Infect. Dis. Mar. 2020;26:ciaa325. doi: 10.1093/cid/ciaa325. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clements J.D., Freytag L.C. Parenteral vaccination can be an effective means of inducing protective mucosal responses. Clin. Vaccin. Immunol. 2016;23:438–441. doi: 10.1128/CVI.00214-16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Docea A.O., Tsatsakis A., Albulescu D., Cristea O., Zlatian O., Vinceti M., Moschos S.A., Tsoukalas D., Goumenou M., Drakoulis N., Dumanov J.M. A new threat from an old enemy: Re-emergence of coronavirus. Int. J. Mol. Med. 2020;45:1631–1643. doi: 10.3892/ijmm.2020.4555. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ganneru B., Jogdand H., Dharam V.K., Molugu N.R., Prasad S.D., Vellimudu S., Ella K.M., Ravikrishnan R., Awasthi A., Jose J., Rao P. bioRxiv; 2020. Evaluation of Safety and Immunogenicity of an Adjuvanted, TH-1 Skewed, Whole Virion Inactivated SARS-CoV-2 Vaccine-Bbv152. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Gao Q., Bao L., Mao H., Wang L., Xu K., Yang M., Li Y., Zhu L., Wang N., Lv Z., Gao H. Development of an inactivated vaccine candidate for SARS-CoV-2. Science. 2020;369:77–81. doi: 10.1126/science.abc1932. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goumenou M., Sarigiannis D., Tsatsakis A., Anesti O., Docea A.O., Petrakis D., Tsoukalas D., Kostoff R., Rakitskii V., Spandidos D.A., Aschner M. COVID-19 in Northern Italy: an integrative overview of factors possibly influencing the sharp increase of the outbreak. Mol. Med. Rep. 2020;22:20–32. doi: 10.3892/mmr.2020.11079. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Holmgren J., Czerkinsky C. Mucosal immunity and vaccines. Nat. Med. 2005;11:S45–S53. doi: 10.1038/nm1213. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Imai M., Iwatsuki-Horimoto K., Hatta M., Loeber S., Halfmann P.J., Nakajima N., Watanabe T., Ujie M., Takahashi K., Ito M. Syrian hamsters as a small animal model for SARS-CoV-2 infection and countermeasure development. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 2020;117:16587–16595. doi: 10.1073/pnas.2009799117. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Islam M.T., Nasiruddin M., Khan I.N., Mishra S.K., Kudrat-E-Zahan M., Riaz T.A., Ali E.S., Rahman M.S., Mubarak M.S., Martorell M., Cho W.C. A perspective on emerging therapeutic interventions for COVID-19. Front. Public Health. 2020;8:281. doi: 10.3389/fpubh.2020.00281. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krammer F. SARS-CoV-2 vaccines in development. Nature. 2020;586:516–527. doi: 10.1038/s41586-020-2798-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li Q., Guan X., Wu P., Wang X., Zhou L., Tong Y., Ren R., Leung K.S.M., Lau E.H.Y., Wong J.Y. Early transmission dynamics in Wuhan, China, of novel coronavirus–infected pneumonia. N. Engl. J. Med. 2020;382:1199–1207. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa2001316. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Luan J., Lu Y., Jin X., Zhang L. Spike protein recognition of mammalian ACE2 predicts the host range and an optimized ACE2 for SARS-CoV-2 infection. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 2020;526:165–169. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2020.03.047. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lv Z., Deng Y.Q., Ye Q., Cao L., Sun C.Y., Fan C., Huang W., Sun S., Sun Y., Zhu L. Structural basis for neutralization of SARS-CoV-2 and SARS-CoV by a potent therapeutic antibody. Science. 2020;369:1505–1509. doi: 10.1126/science.abc5881. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mohandas S., Jain R., Yadav P.D., Shete-Aich A., Sarkale P., Kadam M., Kumar A., Deshpande G., Baradkar S., Patil S. Evaluation of the susceptibility of mice & hamsters to SARS-CoV-2 infection. Indian J. Med. Res. 2020;151:479. doi: 10.4103/ijmr.IJMR_2235_20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pandey S.C., Pande V., Sati D., Upreti S., Samant M. Vaccination strategies to combat novel corona virus SARS-CoV-2. Life Sci. 2020;256:117956. doi: 10.1016/j.lfs.2020.117956. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Phan L.T., Nguyen T.V., Luong Q.C., Nguyen T.V., Nguyen H.T., Le H.Q., Nguyen T.T., Cao T.M., Pham Q.D. Importation and human-to-human transmission of a novel coronavirus in Vietnam. N. Engl. J. Med. 2020;382:872–874. doi: 10.1056/NEJMc2001272. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reynolds H.Y. Immunoglobulin G and its function in the human respiratory tract. Mayo Clinic Proc. 1988;63:161–174. doi: 10.1016/s0025-6196(12)64949-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roberts A., Vogel L., Guarner J., Hayes N., Murphy B., Saki S., Subbarao K. Severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus infection of golden Syrian hamsters. J.Virol. 2005;79:503–511. doi: 10.1128/JVI.79.1.503-511.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rogers T.F., Zhao F., Huang D., Beutler N., Burns A., He W.T., Limbo O., Smith C., Song G., Woehl J., Yang L. Isolation of potent SARS-CoV-2 neutralizing antibodies and protection from disease in a small animal model. Science. 2020;369:956–963. doi: 10.1126/science.abc7520. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sanders B., Koldijk M., Schuitemaker H. Vaccine Analysis: Strategies, Principles, and Control. Springer; 2015. Inactivated viral vaccines; pp. 45–80. [Google Scholar]

- Sia S.F., Yan L.M., Chin A.W., Fung K., Choy K.T., Wong A.Y., Kaewpreedee P., Perera R.A., Poon L.L., Nicholls J.M. Pathogenesis and transmission of SARS-CoV-2 in golden hamsters. Nature. 2020;583:834–838. doi: 10.1038/s41586-020-2342-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- The Centre for Evidence-Based Medicine Global Covid-19 case fatality rates. 2020. https://www.cebm.net/covid-19/global-covid-19-case-fatality-rates/

- Tostanoski L.H., Wegmann F., Martinot A.J., Loos C., McMahan K., Mercado N.B., Yu J., Chan C.N., Bondoc S., Starke C.E., Nekorchuk M. Ad26 vaccine protects against SARS-CoV-2 severe clinical disease in hamsters. Nat. Med. 2020;26:1694–1700. doi: 10.1038/s41591-020-1070-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tsatsakis A., Calina D., Falzone L., Petrakis D., Mitrut R., Siokas V., Pennisi M., Lanza G., Libra M., Doukas S.G., Doukas P.G. SARS-CoV-2 pathophysiology and its clinical implications: an integrative overview of the pharmacotherapeutic management of COVID-19. Food Chem. Toxicol. 2020;146:111769. doi: 10.1016/j.fct.2020.111769. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van Doremalen N., Lambe T., Spencer A., Belij-Rammerstorfer S., Purushotham J.N., Port J.R., Avanzato V.A., Bushmaker T., Flaxman A., Ulaszewska M. ChAdOx1 nCoV-19 vaccine prevents SARS-CoV-2 pneumonia in rhesus macaques. Nature. 2020;586:578–582. doi: 10.1038/s41586-020-2608-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang H., Zhang Y., Huang B., Deng W., Quan Y., Wang W., Xu W., Zhao Y., Li N., Zhang J. Development of an inactivated vaccine candidate, BBIBP-CorV, with potent protection against SARS-CoV-2. Cell. 2020;182:713–721. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2020.06.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang Y., Miao J., Chard L., Wang Z. Syrian hamster as an animal model for the study on infectious diseases. Front. Immunol. 2019;10:2329. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2019.02329. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wilder-Smith A., Chiew C.J., Lee V.J. Can we contain the COVID-19 outbreak with the same measures as for SARS? Lancet Infect. Dis. 2020;20:E102–E105. doi: 10.1016/S1473-3099(20)30129-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- World Health Organization Coronavirus disease (COVID-19) outbreak situation. 2020. https://www.who.int/emergencies/diseases/novel-coronavirus-2019

- World Health Organization . 2020. Draft Landscape of COVID-19 Candidate Vaccines.https://www.who.int/who-documents-detail/draft-landscape-of-covid-19-candidate-vaccines 28 August 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Yadav P., Ella R., Kumar S., Patil D., Mohandas S., Shete A., Bhati G., Sapkal G., Kaushal H., Patil S. Remarkable immunogenicity and protective efficacy of BBV152, an inactivated SARS-CoV-2 vaccine in rhesus macaques. Res. Square. 2020 doi: 10.21203/rs.3.rs-65715/v1. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Yu J., Tostanoski L.H., Peter L., Mercado N.B., McMahan K., Mahrokhian S.H., Nkolola J.P., Liu J., Li Z., Chandrashekar A., Martinez D.R. DNA vaccine protection against SARS-CoV-2 in rhesus macaques. Science. 2020;369:806–811. doi: 10.1126/science.abc6284. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

The published article includes all data sets generated or analyzed during this study.