Abstract

The present study aimed at evaluating clinical utility of periosteal pedicle graft with coronally advanced flap (PPG + CAF) vs modified coronally advanced flap (M-CAF) in cases of multiple adjacent gingival recessions involving maxillary and mandibular anteriors labially. Random allocation of 40 patients with 269 gingival recessions was done into two groups. In Test group (20 patients) periosteal pedicle graft followed by coronally advanced flap (PPG + CAF) technique was performed and in control group (20 patients) modified coronally advanced flap (M-CAF) was attempted. Primary outcome measures included percentage root coverage (PRC), gingival thickness (GT), probing depth (PD), clinical attachment level (CAL), recession depth (RD) and width of keratinized gingiva (WKG). Secondary outcomes measures were patient centred outcomes, plaque index (PI) and gingival index (GI). Patients were recalled at baseline, 3,6 and 18 months postoperatively.

Results

There was a significant decrease in the mean recession depth from 3.58 ± 0.53 mm (baseline) to 0.22 ± 0.01 mm (18 months) in PPG + CAF test group and 3.7 ± 0.56 mm (baseline) to 0.21 ± 0.01 mm (18 months) in M-CAF control group. With 85% root coverage in test group and 78% root coverage in control group, the difference was statistically significant at 18 months. The test group showed significant higher clinical attachment level gain and increase in width of keratinized gingiva as compared to control group.

Conclusion

In both the study groups PPG + CAF and M-CAF, significant root coverage was achieved. However, in terms of increase in width of keratinized gingiva, gingival thickness and percentage root coverage, PPG + CAF group presented significantly better results than M-CAF group at 18 months follow up. Thus, periosteum can be used as a pedicle graft along with coronally advanced flap as an alternative method in achieving better results with minimal cost.

Keywords: Aesthetics, Coronally advanced flap, Gingival recession, Modified coronally advanced flap, Multiple gingival recessions, Periosteal pedicle flap, Periosteum, Root coverage

1. Introduction

Gingival recession is a result of lost periodontal tissues and it needs management to prevent further breakdown and restore periodontal health. Gingival recession can be localized or generalized that can cause difficulty in oral hygiene maintenance,hypersensitivity, mobility and esthetic concern.1Multiple adjacent recessions are difficult to treat as the surgical field is large, involving factors like root anatomy, bony dehiscence, residual keratinized tissue, patients overall health and acceptance to treatment protocols.2Other factors are the amount of donor tissue that can be obtained for covering the recession area from palate, maxillary tuberosity and other areas and the number of surgical procedures to be taken to get the desired results. Several surgical techniques have been illustrated with the aim of complete root coverage and esthetic harmony with the surrounding tissues. Single or combination of techniques have been implemented with connective tissue grafts, bone grafts as a regenerative strategies to regain the lost periodontal tissues along with coronally advanced flap (CAF).3

Zucchelli and De Santis described a modified coronally advanced flap(M-CAF)technique in cases of multiple gingival recession using split-full-split thickness flap.4 This technique results in tension free closure of flap, maintains flap thickness and obliterates the use of vertical incision promoting wound healing. Closure of vertical incision becomes challenging in inaccessible areas like posterior maxilla sometimes and so M-CAF is a predictable option in management of multiple gingival recession defects.

Recently, periosteum as a pedicle graft (PPG) along with coronally advanced flap was introduced in the management of gingival recession defects with promising results.5The rationale behind the use of periosteum as a pedicle graft is its high vascularity, osteogenic potential, rich source of fibroblasts, osteoblasts and stem cells.6 It eliminates the need of second surgical donor site, reduces surgical time, cost and patients apprehension. Periosteal pedicle graft has its own blood supply which gives a better chance of adaptation and revascularization in the surgical site. Thus, the present study aimed at evaluation of clinical efficacy of periosteal pedicle graft with CAF and modified coronally advanced flap (M-CAF)in maxillary and mandibular anterior teeth in labial multiple gingival recession defects treatment. In both the treatment procedures, the flap retains its own blood supply, eliminates any second surgical site or addition of any foreign graft or membrane and so such similar comparisons can give us better insight to their effectiveness. It is hypothesized that when periosteum is used as graft, it promotes regeneration of lost periodontal tissues in the treatment site. Periosteum has osteogenic potential, is a rich source progenitor cells and stem cells .7 These cells are capable of regenerating the lost periodontal tissues i.e. cementum, periodontal ligament and alveolar bone.

2. Materials and methods

2.1. Study settings

This was a randomized, controlled, parallel arm, trial with 18-months follow-up. Subjects attending outpatient department of periodontology from October 2015 to December 2016 were included in the study. A total of 40 subjects with chief complaint of dentinal hypersentivity and elongation of teeth participated in the study. The study was approved by the Institutional ethical committee, J.S.S Academy of Higher Education and Research. All the study procedures were performed after written informed consent by the subjects.

Inclusion Criteria.

-

•

Subjects having age 18–60 years

-

•

Systemically healthy subjects

-

•

Full-mouth plaque score (FMPS)8 and full-mouth bleeding score(FMBS) < 15%9

-

•

Multiple adjacent teeth (≥3) having Miller Class I and II recession defects10 (≥1 mm in depth) in the maxilla or mandible region.

-

•

No past history of any periodontal surgery in the recession defect area.

-

•

Teeth involving recession defect had no caries or restoration.

-

•

Cementoenamel junction (CEJ) dentifiable.

Exclusion criteria were.

-

•

Any conditions contraindicated for periodontal surgery

-

•

Subjects on medications interfering periodontal healing.

2.2. Clinical parameters

Clinical measurements were recorded by single examiner (PS) masked to surgical procedure throughout the study duration. Following measurements were taken using UNC- 15 probe (PCP-UNC-15 probe, Hu-Friedy, Chicago, IL, USA).

Distance from gingival margin to the base of the gingival sulcus was considered as probing pocket depth (PPD).

Recession depth (RD) was the vertical depth of the recession measured from the cementoenamel junction (CEJ) to the gingival margin. 50 defects were examined with thrice repetition and a Cohen’s kappa of 0.86 was obtained.

Clinical attachment level (CAL) was measured from the CEJ to the base of the gingival sulcus.

Width of the keratinized gingival (WKG) was measured from the mucogingival junction to the gingival margin.

Gingival thickness (GT) was measured in an area 1.5 mm apical to the gingival margin with the help of endodontic spreader having rubber stopper. The spreader was inserted perpendicularly to the gingival surfaces till bony resistance was felt. The distance was measured with digital calliper and rounded to the nearest 0.1 mm.11

Percentage of root coverage was calculated as12

Plaque index13 and gingival index14 was recorded at baseline, 3,6, 12 and 18 months.

Patient centred outcomes like reduction in dentin hypersensitivity, colour of gingiva, intraoperative pain/discomfort, post operative complications, cost effectiveness, were also recorded. These outcomes were recorded dichotomously (score 0 was given to no/not satisfied and score 1 means yes/satisfied). Duration of the surgery was also recorded.

Root esthetic score15 as described by Cairo et al. was used for esthetic evaluation.

2.3. Sample size

The sample size calculation was based on sample used in previous study.16 Accordingly for a minimal root coverage of clinical significance 1 mm, α = 0.05, a confidence interval (CI) = 95%, 18 patients per group was required. Allowing attrition rate of 20%, 22 patients in each group was decided.

2.4. Randomization

The patients were randomly allocated to either of the treatment group based on computer generated randomization table (GraphPad Prism for Windows 10, La Jolla, CA, USA). Allocation was concealed in coded envelopes and opened at the time of the surgery.

2.5. Pre surgical procedure

Scaling and root planning by ultrasonic scaler and gracey curettes (Hu-Friedy, Chicago, Illinois) were performed in all the enrolled patients followed by maintenance therapy. Oral hygiene instructions included brushing with roll technique using soft bristled toothbrush for 2 months before surgery.

2.6. Surgical procedure

All the surgical interventions were performed by a single clinician (SN). The surgical site was anesthetized with local infiltration of 2% lidocaine with adrenaline 1:80,000 in the maxillary area and in case of mandiblular area, mental block was given on both sides of the premolar area. Patients were advised to rinse with 10 ml of 0.2% Chlorhexidine digluconate mouthwash for 1 min.

2.7. PPG + CAF (test group)

The patients were treated with a combination of periosteal pedicle graft and coronally advanced flap as illustrated by Mahajan.17 An intrasulcular incision was given on the buccal aspect of each tooth involved with 15C (Swann-Morton Ltd., Sheffield, UK) blade followed by a horizontal right angle incision slightly coronal to the CEJ was placed into the adjacent interdental papilla. This horizontal incision was connected by the vertical incisions which was placed divergent extending from the gingival margin to the alveolar mucosa on the two sides of the last tooth involved (Fig. 1a, Fig. 1b, Fig. 1c). A full thickness flap was raised 3–4 mm apical to the bony dehiscence, from this point apically, partial thickness flap was created by sharp dissection to expose adequate periosteum. The exposed periosteum was slowly separated from the apical end using periosteal elevator (Hu-freidy P-24) from the underlying bone, while care was taken that it remained attached at it coronal most ends. De-epithelisation of the papillae adjacent to the defect was performed.

Fig. 1a.

Baseline situation showing multiple gingival recessions in the mandible with tobacco stains before oral prophylaxis.

Fig. 1b.

Baseline situation showing multiple gingival recessions in the mandible at the surgery day.

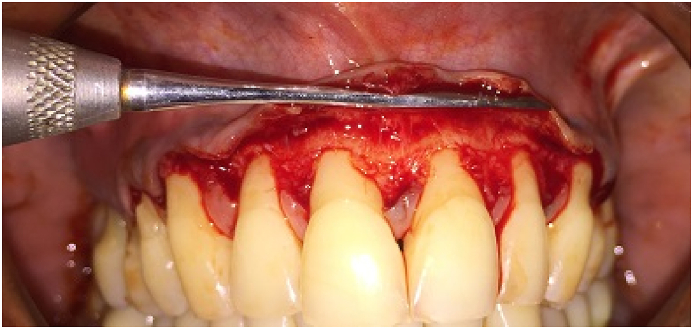

Fig. 1c.

Full thickness flap reflected 3–4 mm apical to gingival margin and then split thickness flap reflected, exposing the underlying periosteum.

The periosteum as a pedicle graft was harvested and inverted over the exposed root surface (Fig. 1d, Fig. 1e).

Fig. 1d.

The periosteum is slowly detached from its apical end while care is taken that it is attached at the coronal most end and everted slowly to cover the exposed root surface.

Fig. 1e.

the apically detached periosteal pedicle graft is stabilised on the root surface, covering the recession defects.

No sutures were placed to stabilise the PPG coronally as it remained stable over the root surface. This modification was done from conventional PPG technique to reduce the time and suture expense. The PPG covering the denuded root surface was completely covered with coronally advanced flap and stabilised with resorbable vicryl suture (4–0) (Ethicon, Johnson & Johnson, Aurangabad, India) using sling sutures. Interrupted sutures were placed to close the releasing incisions (Fig. 1f). The surgical area was covered with noneugenol periodontal dressing (Coepack, GC America).

Fig. 1f.

Coronally advanced flap covering the periosteal pedicle graft and stabilised with sling sutures.

2.8. M-CAF (control group)

Coronally advanced flap as modified by Zucchelli and De Sanctis was performed.4 An envelope flap was designed by placing oblique submarginal incisions at the interdental areas and intrasulcular incisions were placed using a15C blade (Fig. 2a, Fig. 2ba and b). The oblique incisions started at the cementoenamel junction of the central tooth involved. The flap was elevated with a split-full-split approach in the corono-apical direction. Split thickness flap was elevated in the most apical part of the flap to provide tension free coronal advancement (Fig. 2c). The interdental papillae were de-epithelialized and the modified coronally advanced flap was positioned coronally to the CEJ and secured using resorbable vicryl sling sutures. To immobilize the gingival margin which is critical during healing phase composite bonded coronally anchored sutures were placed for 3 weeks for better stability of the flap coronally (Fig. 2 d).

Fig. 2a.

Baseline situation showing multiple gingival recessions in the maxilla.

Fig. 2b.

Oblique submarginal incisions at the interdental areas.

Fig. 2c.

Split-full-split thickness flap reflected.

Fig. 2d.

Coronally advanced flap covering the recession defects and stabilised using sling and coronally anchored bonded sutures.

2.9. Postsurgical care

Patients were given an ice bag to be applied intermittently for the first 4 h following surgery. They were prescribed amoxicillin 500 mg thrice daily for 5 days and diclofenac sodium 50 mg twice daily for 3 days. Patients were advised to avoid any mechanical trauma and brushing for next 2 weeks. To maintain oral hygiene they were instructed to rinse mouth with chlorhexidine digluconate 0.2% mouthwash twice daily for at least 2 weeks. At 1 week follow up, removal of the periodontal dressing was done and the area was flushed with normal saline. Patients were recalled on regular basis for necessary prophylaxis and oral hygiene reinforcement every 3 months and then 6 months interval till the completion of the study (Fig. 1g, Fig. 1h, Fig. 1i, Fig. 2e, Fig. 2f).

Fig. 1g.

2 weeks follow up post surgery.

Fig. 1h.

3 months postoperative.

Fig. 1i.

Clinical outcome at 18 months post operative.

Fig. 2e.

2 weeks post operative follow up.

Fig. 2f.

Clinical outcome at 18 months post operative.

2.10. Statistical analysis

Statistical analyses were performed with a statistical software (SPSS for WindowsVersion16.0, SPSS Inc.,Chicago,IL). Descriptive statistics for quantitative data were presented as means and standard deviation and as percentage for qualitative data. Repeated measure anova and two-tailed Wilcoxon’s signed-rank tests was done for comparison of different techniques on RD, PPD, CAL, WKG parameters at different interval of time. Chi-square test was done for qualitative data. The results were statistically significant at p < 0.05.

3. Results

A total of 40 patients with mean age 38.2 ± 5 years (22 women, 18 males) diagnosed with multiple gingival recessions were treated by a single clinician (Fig. 3). 12 patients were smokers and 5 patients gave history of smokeless tobacco. In the test group 5 patients were smokers and 3 consumed smokeless tobacco and in the control group there were 7 smokers and 2 smokeless tobacco patients.Patients were advised to quit smoking 6 weeks before the surgical procedure and were counselled to quit the habit altogether. All the patients presented with good oral hygiene throughout the study period (FMPS < 20%;FMBS < 20%). The patients reported no postoperative complications except for 1 having postoperative edema in test group which subsided in 14 days.

Fig. 3.

Study participants.

Treatment of 269 gingival recessions was done. Gingival recessions in 18 patients were in anterior maxilla with 64 areas treated by PPG + CAF and 59 by M-CAF. 146 (22 patients) with gingival recession were treated in the anterior mandible with 72 recessions were treated with PPG + CAF and 74 with M-CAF. No statistical significant difference was seen in between the two treatment procedure in relation to treated areas (p > 0.05).

3.1. Plaque index

In the test group (PPG + CAF) the FMPS score reduced from 0.67 ± 0.23 (baseline) to 0.23 ± 0.18 at 3 months and in control group (M-CAF) from 0.63 ± 0.14 (baseline) to 0.21 ± 0.13 at 3 months.

This reduction in plaque score was statistically significant (p < 0.05). Further, statistical increase at 6, 12 and 18 months in either groups was not seen (p > 0.05) (Table 1).

Table 1.

Clinical Parameters and Intergroup Comparison of Primary and Secondary outcomes.

| Clinical para-meter | Baseline Group |

3 months Group |

6 months Group |

12 months Group |

18 months Group |

p-value | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Test | Control | Test | Control | Test | Control | Test | Control | Test | Control | ||

| RD (mm) | 3.58 ± 0.53 | 3.7 ± 0.56 | 0.46 ± 0.9 | 0.38 ± 0.15 | 0.37 ± 0.9 | 0.33 ± 0.10 | 0.27 ± 0.14 | 0.23 ± 0.11 | 0.22 ± 0.8 | 0.21 ± 0.7 | <0.05 |

| PD (mm) | 1.14 ± 0.12 | 1.15 ± 0.11 | 0.64 ± 0.12 | 0.68 ± 0.11 | 0.62 ± 0.13 | 0.67 ± 0.11 | 0.61 ± 0.13 | 0.65 ± 0.15 | 0.65 ± 0.11 | 0.66 ± 0.14 | >0.05 |

| CAL (mm) | 4.46 ± 0.21 | 4.34 ± 0.21 | 1.15 ± 0.02 | 1.16 ± 0.02 | 1.13 ± 0.01 | 1.14 ± 0.03 | 1.07 ± 0.06 | 1.05 ± 0.07 | 1.06 ± 0.06 | 1.04 ± 0.08 | >0.05 |

| WKG (mm) | 3.02 ± 0.27 | 3.09 ± 0.32 | 3.38 ± 0.11 | 3.36 ± 0.18 | 5.87 ± 0.16 | 5.19 ± 0.14 | 5.83 ± 0.17 | 5.11 ± 0.13 | 5.85 ± 0.12 | 5.02 ± 0.11 | <0.05 |

| GT | 1.02 ± 0.35 | 1.25 ± 0.33 | 1.36 ± 0.33 | 1.28 ± 0.24 | 1.37 ± 0.23 | 1.29 ± 0.22 | 1.36 ± 0.25 | 1.28 ± 0.23 | 1.37 ± 0.13 | 1.28 ± 0.15 | <0.05 |

| PI | 0.67 ± 0.23 | 0.63 ± 0.14 | 0.23 ± 0.18 | 0.21 ± 0.13 | 0.01 ± 0.01 | 0.02 ± 0.02 | 0.03 ± 0.01 | 0.04 ± 0.01 | 0.02 ± 0.01 | 0.01 ± 0.03 | >0.05 |

| GI | 0.01 ± 0.01 | 0.02 ± 0.01 | 0.01 ± 0.02 | 0.01 ± 0.01 | 0.01 ± 0.02 | 0.01 ± 0.01 | 0.01 ± 0.03 | 0.02 ± 0.01 | 0.02 ± 0.01 | 0.02 ± 0.02 | >0.05 |

| RES | 7.87 ± 0.52 | 7.81 ± 0.47 | >0.05 | ||||||||

| CRC (%) | 85.23 ± 2.31 | 78.31 ± 0.78 | <0.05 | ||||||||

RD = gingival recession depth; CRC = complete root coverage; PD = probing depth;CAL = clinical attachment level.

WKG = Width of keratinized gingiva; RC = root coverage; PI = plaque index; GI = gingival index,GT = gingival thickness,RES = root esthetic score,∗Intergroup p value.p < 0.05 statistically significant.

3.2. Gingival index

In both the groups statistically significant decrease in gingival index was seen from baseline to 3 months, however no statistical difference in between or within the group was seen at 6,12 and 18 months duration(p > 0.05) (Table 1).

3.3. Gingival recession depth

In the test group, the mean recession depth (RD) at baseline was 3.5 ± 0.53 mm which was reduced to 0.22 ± 0.11 mm at 18 months. In the control group, the mean RD at baseline was 3.7 ± 0.56 mm which reduced to 0.21 ± 0.14 mm at 18 months. This reduction was statistically significant (p < 0.05) in between and within the both the groups (p < 0.05) (Table 2).

Table 2.

Intergroup comparison of different patient- centred outcome.

| Test(mean ± SD) | Control(mean ± SD) | p value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Duration of surgery(min) | 76 ± 3.68 | 61.27 ± 2.72 | <0.05 |

| Intraoperative Pain | 9.5 ± 1.1 | 8.1 ± 1.3 | <0.05 |

| Cost effectiveness(mean %) | 86 ± 1.3 |

85 ± 1.4 |

>0.05 |

| Color(mean%) | 90.9 ± 9.1 |

95.5 ± 4.5 |

>0.05 |

| Dentin hypersensitivity(mean%) | 89.9 ± 8.1 |

86.4 ± 13.6 |

>0.05 |

Intergroup p value. P < 0.05 statistically significant, SD-standard deviation.

3.4. Percentage root coverage

PPG + CAF group showed 85.23 ± 2.31% mean percentage root coverage at 18 months duration whereas M-CAF group showed 78.31 ± 0.78% at 18 months. This difference was statistically significant, test group showing higher mean root coverage percentage as compared to control group (p < 0.05) (Table 1).

3.5. Width of keratinized gingiva

Mean width of keratinized gingiva increased 3.02 ± 0.27 mm (baseline) to 5.85 ± 0.12 mm (18 months) in test group. In the control group it increased 3.09 ± 0.32 mm to 5.12 ± 0.11 mm. This increase was statistically significant within the group (p < 0.05). The test group showed statistical increase in WKG at 18 months duration when compared to control group (p < 0.05) (Table 1).

3.6. Clinical attachment level

In the test group mean CAL was 4.46 ± 0.21 mm (baseline) to 1.06 ± 0.06 mm at 18 months with a mean gain of 3.40 ± 0.15 mm. The mean CAL was 4.34 ± 0.21(baseline) to 1.04 ± 0.08 mm at 18 months, a mean gain of 3.30 ± 0.13 mm.This CAL gain from baseline to 18 months was statistically significant within the group(p < 0.05). However in between the groups no significant difference was seen(p > 0.05) (Table 1).

3.7. Probing depth

In the test group the mean probing depth was 1.14 ± 0.12 mm (baseline) and reduced to 0.65 ± 0.11 mm at 18 months. In the control group the mean reduction was 1.15 ± 0.11 mm (baseline) to 0.66 ± 0.14 mm at 18 months. This reduction was statistically significant (p < 0.05) within the group but not between the groups (p > 0.05) (Table 1).

3.8. Gingival thickness

The thickness of gingiva increased from 1.02 ± 0.35 mm baseline to 1.37 ± 0.13 mm at 18 months in the test group. In the control group this increase was 1.25 ± 0.33 mm (baseline) to 1.28 ± 0.15 mm at 18 months. The increase in gingival thickness was statistically significant in test group when compared to control group (p < 0.05) and within the group, statistical significance was seen in test group only (p < 0.05) (Table 1).

3.9. Root esthetic score

Mean root esthetic score was 7.87 ± 0.52 in test group and 7.81 ± 0.47 in control group. This difference was statistically insignificant (p > 0.05) (Table 1).

3.10. Patient centred outcomes

In both the groups patients reported favourable colour match and no significant difference was seen (p > 0.05). Increase intraoperative pain was observed in test group as compared to control groups(p < 0.05). This difference was statistically significant (p > 0.05). Patients reported statistically significant reduction in dentin hypersentivity in test group as compared to control groups. No statistical difference in cost effectiveness was reported by patients in between the groups (p > 0.05) (Table 3).

Table 3.

Clinical Difference Between Change in Clinical Parameters (mean ± SD, in mm) PPG + CAF and M-CAF After 12 Months.

| Clinical Parameter | Test group | Control group | p value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Gingival recession Reduction |

3.36 ± 0.42 | 3.49 ± 0.45 | <0.05 |

| Change in probing Depth |

0.49 ± 0.1 | 0.49 ± 0.1 | >0.05 |

| Width of keratinized gingiva |

2.83 ± 0.15 | 2.93 ± 0.21 | <0.05 |

| Gingival thickness | 0.35 ± 0.22 | 0.03 ± 0.18 | <0.05 |

p < 0.05 statistically significant, SD-standard deviation.

4. Discussion

The results of the present study illustrate that the surgical technique combining modified CAF with PPG is effective in management of multiple adjacent gingival recession defects.

To the authors knowledge there are no randomised clinical trials comparing PPG + CAF and M-CAF and so direct comparison of results with other studies was not feasible. However, a case series on evaluating the effectiveness of PPG + CAF and CAF alone showed PPG + CAF group having more predictable percentage of root coverage and superior esthetic outcomes for multiple gingival recession defects treatment.18 The results of this case series are in accordance with our study, in the present study percentage of root coverage in test group was 85.23 ± 2.31% as compared to control group 78.31 ± 0.78% at 18 months follow up. This can be attributed to the periosteum when used as a pedicle graft renders a highly vascular area favouring new attachment and wound healing in underlying avascular root surface. Periosteal cells are rich source of vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) promoting angiogenesis, bone formation and wound healing.19 Thus, when periosteum itself is used as a graft, it promotes revascularization, regeneration and early wound healing, thereby creating better chance of graft survival. Lekovic et al. used PPG as an autologous barrier membrane in the treatment of Grade II furcation defects and found significant reduction in pocket depth and gain in attachment level.20

Stability of root coverage depends on various factors like intraoperative techniques used, postoperative care.21 Gingival thickness is an important factor contributing to the stability of recession coverage. Thin gingival margins are more vulnerable to future recession if the gingiva is of thin biotype. Periosteum as a membrane might increase the chance of achieving greater gingival thickness post operatively. This was seen in the present study, gingival thickness was significantly increased in the test group when compared to control group at 18 months.

Another randomised controlled trial having split mouth study design compared PPG with vestibular incision sub-periosteal tunnel access(VISTA) technique using Bio-Guide membrane with GEM 21S demonstrated that significant recession reduction was seen in both the groups.22 However, clinical attachment gain and width of keratinized tissue were significantly higher in the VISTA group compared with the PPG group. This might be due to additional use of bone graft GEM 21S rendering more favourable environment for regeneration as compared with periosteum when used as a membrane only.

WKG increased significantly in both the groups at 3 months but the increase was statistically significant at 18 months in test group as compared to control. This indicates potential long term stability of periosteal pedicle graft in achieving width of keratinized tissue. Connective tissues grafts are known for increasing the width of keratinized gingiva by epithelialization known as induction mechanism. Periosteum having rich source of fibroblasts, osteoblasts, progenitor cells and mesenchymal stem cells might be capable in inducing similar mechanism achieving keratinization.23 The results of the present study is similar to the case series presentation by Mahajan et al. in which mean WKG increase of 0.12 ± 0. 02 mm was seen with clinical significance p<0.00010.17

In both the groups PD reduction and CAL gain was significant from baseline to 18 months postoperatively. In the present study, mean gain in CAL in both groups was 3.5 mm.This represents formation of new attachment throughout the defect. True analysis of the level and type of attachment is only possible on surgical re-entry which was difficult due to ethical issues. However, in a study by Steiner et al. normal periodontal architecture was found on surgical entry after use of inverted periosteal graft.24 This suggests the possible reason for reduction in PD and CAL gain significantly seen in this study.

Patient centred outcomes, reduction in dentin hypersensitivity was seen significantly at 3 months in both the groups and the results sustained over a period of 18 months in both the groups(p < 0.05). No statistically significant difference in the colour of gingiva was observed between the groups. However, in PPG group more surgical duration was taken to complete the procedure as compared with the control group as longer time was required in harvesting the periosteal pedicle graft when compared to modified coronally advanced flap (Table 2).

This could be also a possible reason for more intraoperative significant discomfort was reported in the test group.

4.1. Limitations of the study

Histologic assessment of the type of attachment was not performed due to ethical considerations. Split mouth study design would have given more comparable results. Longer duration of follow up would have helped us to critically evaluate results stability.

5. Conclusion

The success of root coverage procedures lies in percentage of root coverage, patient centred outcomes like esthetic satisfaction, relief from chief complain like dentin hypersensitivity. This gives us scope of new treatment strategies to explore possible success in all the aspects. In developing countries the choice of treatment is dependent on cost effectiveness of the procedure along with less postsurgical pain. The use of PPG reduces cost without compromising the chance of successful recession coverage. Thus, we conclude that the use of periosteal pedicle graft along with coronally advanced flap is a viable treatment procedure in achieving optimal patient based recession outcomes.

Funding statement

The study was self funded.

Declaration of competing interest

No conflicts of interest was reported by the authors associated to this study.

Contributor Information

Swet Nisha, Email: swetnisha1@gmail.com.

Pratibha Shashikumar, Email: dr.pratibhashashikumar@jssuni.edu.in.

References

- 1.Wennstrom J.L. Mucogingival therapy. Ann Periodontol. 1996;1:671–701. doi: 10.1902/annals.1996.1.1.671. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hofmanner P., Alessandri R., Laugisch O. Predictability of surgical techniques used for coverage of multiple adjacent gingival recessions—a systematic review. Quintessence Int. 2012;43:545–554. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Cairo F., Pagliaro U., Nieri M. Treatment of gingival recession with coronally advanced flap procedures: a systematic review. J Clin Periodontol. 2008;35(8 Suppl):s136–s162. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-051X.2008.01267.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Zucchelli G., De Sanctis M. Treatment of multiple recession-type defects in patients with esthetic demands. J Periodontol. 2000;71:1506–1514. doi: 10.1902/jop.2000.71.9.1506. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Mahajan A. Periosteal pedicle graft for the treatment of gingival recession defects: a novel technique. Aust Dent J. 2009;54:250–254. doi: 10.1111/j.1834-7819.2009.01128.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Augustin G., Antabak A., Davila S. The periosteum Part 1: anatomy, histology and molecular biology. Injury. 2007;38:1115–1130. doi: 10.1016/j.injury.2007.05.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Mizuno H., Hata K.I., Kojima K., Bonassar L.J., Vacanti C.A., Ueda M. A novel approach to regenerating periodontal tissue by grafting autologous cultured periosteum. Tissue Eng. 2006;12:1227–1335. doi: 10.1089/ten.2006.12.1227. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.O’Leary T.J., Drake R.B., Naylor J.E. The plaque control record. J Periodontol. 1972;43:38. doi: 10.1902/jop.1972.43.1.38. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ainamo J., Bay I. Problems and proposals for recording gingivitis and plaque. Int Dent J. 1975;25:229–235. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Miller P.D., Jr. A classification of marginal tissue recession. Int J Periodontics Restor Dent. 1985;5:8–13. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Marques de Araujo Lidya Nara, Batista Borges Samuel, Targino dos Santos Matheus, Costa Lima Kenio, de Vasconcelos Gurgel Bruno César. Assessment of gingival phenotype through periodontal and crown characteristics: a cluster analysis. J Int Acad Periodontol. 2020;22/1:21–28. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Paolantonio M. Treatment of gingival recession by combined periodontal regenerative technique,guided tissue regeneration and subpedicle connective tissue graft.A comparative clinical study. J Periodontaol. 2002;73:53–62. doi: 10.1902/jop.2002.73.1.53. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Silness J., Loe H. Periodontal disease in pregnancy. II. Correlation between oral hygiene and periodontal conditions. Acta Odontol Scand. 1964;22:121–135. doi: 10.3109/00016356408993968. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Loe H., Silness J. Periodontal disease in pregnancy I. Prevalence and severity. Acta Odontol Scand. 1963;21:533–551. doi: 10.3109/00016356309011240. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Cario F., Rotundo R., Miller P.D., Pini Prato G.P. Root coverage esthetic score: a system to evaluate the esthetic outcome of the treatment of gingival recession through evaluation of clinical cases. J Periodontol. 2009;80:705–710. doi: 10.1902/jop.2009.080565. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Zucchelli G., Mele M., Mazzotti C., Marzadori M., Montebugnoli L., De Sanctis M. Coronally advanced flap with and without vertical releasing incisions for the treatment of multiple gingival recessions: a comparative controlled randomized clinical trial. J Periodontol. 2009;80:1083–1094. doi: 10.1902/jop.2009.090041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Mahajan A. Treatment of multiple gingival recession defects using periosteal pedicle graft: a case series. J Periodontol. 2010;81:1426–1431. doi: 10.1902/jop.2010.100134. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Mahajan A., Asi K.S. Comparison of effectiveness of the novel periosteal pedicle graft technique with coronally advanced flap for the treatment of long-span unesthetic multiple gingival recession defects. Clinical Advances in Periodontics. 2018;8(2):77–83. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Bourke H.E., Sandison A., Hughes S.P., Reichert I.L. Vascular endothelial growth factor in human periosteum- normal expression and response to fracture. J Bone Joint Surg. 2003;85:S1–S4. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Lekovic V., Kenny E.B., Carranza F.A., Martignoni M. The use of autogenous periosteal grafts as barriers for the treatment of Class II furcation involvements in lower molars. J Periodontol. 1991;62:775–780. doi: 10.1902/jop.1991.62.12.775. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Huang L.H., Neiva R.E., Wang H.L. Factors affecting the outcomes of coronally advanced flap root coverage procedure. J Periodontol. 2005;76:1729–1734. doi: 10.1902/jop.2005.76.10.1729. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Dandu S.R., Murthy K.R. Multiple gingival recession defects treated with coronally adavnced flap and either the VISTA technique enhanced with GEM21S or periosteal pedicle graft: a 9 month clinical study. Int.J Periodontics Restorative Dent. 2016;36:231–237. doi: 10.11607/prd.2533. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Mahajan A. Periosteum: a highly underrated tool in dentistry. Int J Dent. 2012;2012:717816. doi: 10.1155/2012/717816. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Steiner G.G., Kallet M.P., Steiner D.M., Roulet D.N. The inverted periosteal graft. Comp Cont Educ Dent. 2007;28:154–161. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]