Abstract

We present a case of a young adult male who was treated successfully for renal AA-amyloidosis secondary to human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) infection using highly active anti-retroviral therapy (HAART). He presented with lobar pneumonia, acute kidney injury, nephrotic syndrome and newly diagnosed HIV infection and was initiated on HARRT and haemodialysis. Kidney biopsy was consistent with amyloid deposition of the AA-type. His clinical condition improved gradually and after 10 months of therapy, he regained sufficient excretory function to become dialysis independent. Two years later, he remained well, with a recovered CD4 count and a glomerular filtration rate of 63 mL/min/1.73 m2. Patients with renal AA-amyloidosis typically present with slowly progressive chronic kidney disease, often leading to end-stage kidney disease within months. To our knowledge, this is the first reported case of biopsy proven renal AA-amyloidosis in a newly diagnosed HIV positive patient to present with acute kidney injury leading to dialysis dependence over a period of 2 weeks, which was successfully treated using HAART.

Keywords: Haemodialysis, Chronic kidney disease, Renal biopsy, Nephrotic syndrome

Introduction

AA-amyloidosis is a systemic disease whose clinical course is characteristically dominated by the renal dysfunction [1]. Patients typically present with nephrotic range proteinuria, nephrotic syndrome and slowly progressive chronic kidney disease (CKD), frequently leading to end-stage kidney disease (ESKD) [2]. Left untreated, AA-amyloidosis carries a rather poor prognosis, especially in patients who progress to ESKD. We present a case of HIV related renal AA-amyloidosis in a patient with no other co-morbidities or risk factors, presenting with nephrotic syndrome and rapidly progressive renal dysfunction, becoming dialysis dependent in a matter of 2 weeks. The patient was successfully treated with HAART, allowing him to come off dialysis after 10 months of therapy. In addition, this case highlights the complexity and challenging diagnosis of renal disease in HIV infected patients, with renal biopsy being of utmost importance for accurate diagnosis and management.

Case history

A 39-year-old male from Liberia presented with a cough productive of blood tinged sputum, left sided pleurisy and lower limb swelling. The swelling had been present for a few weeks, but the cough and pleurisy were present for 3 days. The patient had been treated successfully for pulmonary tuberculosis 10 years previously. There was no other significant past medical history and he was on no regular medications. He admitted to a 20 pack-year smoking history but denied excessive alcohol or intravenous drug use.

Initial examination revealed a temperature of 37.7 °C, blood pressure of 110/70 mmHg and a regular pulse rate of 110 beats/min. His heart sounds were normal and auscultation of the chest revealed left basal coarse crepitations. He had bilateral pitting oedema up to his knees. Abdominal, musculoskeletal and neurological examination was unremarkable.

Initial laboratory investigation showed a white cell count of 13.31 × 109/L with predominant neutrophilia and a C-reactive protein of 383 mg/L (normal range: 0–5 mg/L). Kidney function was deranged with a serum creatinine of 152 µmol/L and blood urea nitrogen of 10.3 mmol/L. Urinalysis detected 500 mg/dL of protein, otherwise bland sediment. Protein was subsequently quantified at 17 g/day and his serum albumin was 25 g/L. The rest of the complete blood count and liver panel were within normal limits. Chest X-ray revealed a left basal consolidation consistent with a lobar pneumonia and old post-tuberculosis changes in the right apex. An ultrasound examination of the kidneys showed swollen kidneys with loss of corticomedullary differentiation, but otherwise normal Doppler signals in both renal artery and vein. The patient was started on intravenous co-amoxiclav 1.2 g 8 hourly.

On day-3, the patient tested positive for human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) with a viral load of 17,800 copies/mL and a CD4 count of 149 cells/mm3. Thus, he was started on Zidovudine 100 mg thrice daily, Lamivudine 50 mg once daily and combined Lopinavir/Ritonavir 200 mg/50 mg 2 tablets twice daily. Further relevant investigations including thyroid function tests, coagulation profile, fibrinogen, anti-nuclear antibody, anti-neutrophil cytoplasmic antibodies, anti-glomerular basement antibody, complement levels, cryoglobulins, serum protein electrophoresis, serum free light chairs, and an infection screen including hepatitis B and hepatitis C serology and tests for syphilis, mycoplasma and legionella were all within normal limits. No organisms were identified in the blood and sputum cultures. Given the history of previous tuberculosis, 3 sputum samples were examined using Ziehl–Neelsen staining and polymerase chain reaction for tuberculosis; all negative. A transthoracic echocardiogram was normal.

The patient never showed features of sepsis syndrome and within the first week of therapy his C-reactive protein almost normalized and the chest related symptoms resolved. However, he had an evolving acute kidney injury (AKI) and on day-7 the serum creatinine reached 480 µmol/L with an estimated glomerular filtration rate (eGFR) of 12 mL/min/1.73 m2. At that point there were no indications for acute haemodialysis and the differential diagnosis was that of HIV associated nephropathy, possibly worsened by an element of acute tubular necrosis due to the underlying pneumonia.

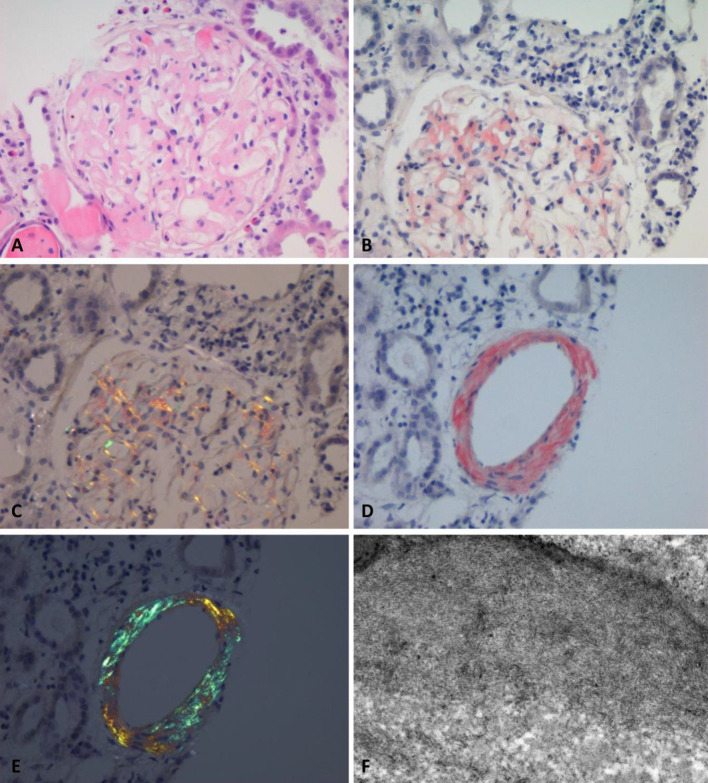

On day-10, his serum creatinine continued rising, reaching 540 µmol/L. The patient was becoming increasingly nephrotic with widespread tissue oedema and a serum albumin of 19 g/L. At this point the patient underwent an ultrasound guided renal biopsy. Light microscopy revealed capillary loop and mesangial thickening with amorphous material in 8 out of 22 glomeruli and in the vascular walls with Congo red staining that displayed apple-green birefringence in keeping with the diagnosis of amyloidosis. A fair number of tubules also appeared to contain eosinophilic and variably Periodic acid-Schiff (PAS) positive cast material. There was also a mild and patchy tubular dilatation with flattening of the lining epithelium. Immunohistochemistry of the amyloid deposits was performed using monospecific antibodies which tested positive for amyloid of the AA-type and negative for kappa and lambda chains. Electron microscopy revealed extensive deposition of fibrillary material in the mesangial and capillary loops, consistent with the light microscopic diagnosis of amyloidosis. No immune deposits or podocyte damage consistent with HIV nephropathy was seen (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1.

a Amyloid deposits under high-power light microscope using Haematoxylin and Eosin stain (× 300). b Glomerular amyloid deposits using Congo red stain (× 300) c Glomerular amyloid deposits showing apple-green birefringence under polarised light (× 300). d Arterial wall amyloid deposits using Congo red stain (× 300). e Arterial wall amyloid deposits showing strong apple-green birefringence under polarised light (× 300). f Electron microscopy showing typical deposition of fibrillary material in the mesangial and capillary loops (× 10,000)

By day-19, his kidney function did not show any signs of recovery and the serum creatinine was in excess of 600 µmol/L (eGFR 10 mL/min/1.73 m2). In addition, he became increasingly oliguric with extensive signs of fluid overload. Thus, the patient was initiated on haemodialysis via a tunnelled intravenous catheter.

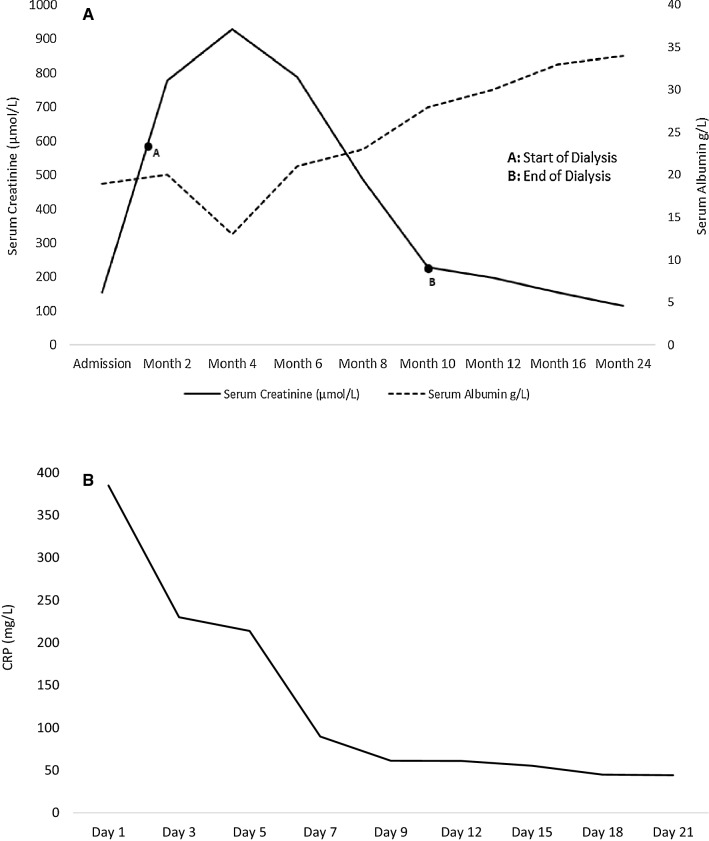

Five days later his fluid status had improved significantly and was discharged with thrice weekly sessions of haemodialysis and weekly follow-up visits. Due to gastrointestinal upset, Lopinavir/Ritonavir was changed to Nevirapine 200 mg once daily with up-titration to twice daily. A repeat chest X-ray was performed 6 weeks later which confirmed complete radiological resolution of the left basal pneumonia. The viral load at 6 months was 1120 copies/mL and the CD4 count was 410 cells/mm3. The patient remained dialysis dependent for a total of 10 months. At that stage, his urine output started to improve and his blood chemistry showed clear signs of amelioration, ultimately managing to stop dialysis altogether (Fig. 2a). Two years later, the patient remained well with an eGFR of 63 mL/min/1.73 m2.

Fig. 2.

a Graph illustrating serum creatinine and serum albumin levels against time for the duration of follow-up. b Graph illustrating CRP against time for the duration admission

Discussion

AA-amyloidosis results from the deposition of insoluble amyloid fibrils derived from circulating serum amyloid-A (SAA) protein, an acute phase reactant associated with many chronic inflammatory conditions [3, 4]. The majority of cases (up to 40%) have been attributed to rheumatic conditions, followed by chronic infections, malignancy, and other inflammatory conditions [5–7]. However, the direct association between HIV infection and AA-amyloidosis has been sporadically documented.

The three stages of HIV infection include acute HIV infection, chronic HIV infection and acquired immunodeficiency syndrome (AIDS). The chronic phase of HIV is characterised by a dynamic balance between the host and the virus and is what determines an individual’s course of disease [8]. Chronic immune activation aimed at reducing the viral replication is the cornerstone of the second stage. Without HAART, progressive decline of the naïve and memory T-cell pool and systemic CD4 T-cell depletion is observed, causing the host-virus balance to tip with a cumulative increase in the viral load [9]. HIV is thus known to result in a chronic inflammatory immune activation and so it is plausible that HIV infection can result in amyloid deposition [10]. SAA have been indeed reported to be present in patients with a CD4 count of < 200 cells/mL [11].

To our knowledge, this is the first reported case of biopsy proven renal AA-amyloidosis in a newly diagnosed HIV positive patient to present with nephrotic syndrome and rapidly progressive renal dysfunction leading to dialysis dependence over a period of 2 weeks. Coelho et al. [11] described a case of HIV related AA-amyloidosis and nephrotic syndrome, albeit maintaining normal excretory function. Cozzi et al. [12] described another case of nephrotic syndrome due to AA-amyloidosis in the context of HIV infection and haemophilia. However, once again, his excretory function remained within normal limits. Kurz et al. [13] described a case series consisting of 11 patients with AKI in HIV positive patients treated with combination antiretroviral therapy. Amongst these cases, one patient was diagnosed with AA-amyloidosis; however, this patient had co-infection with Hepatitis C virus thus raising the question of whether the renal amyloid was the result of HCV infection. De Vallière et al. [14] described a case of renal AA-amyloidosis in the context of HIV infection and concomitant visceral Leishmaniasis in the context of intravenous drug use. Finally, Newey et al. [15] described a case of both renal and gastrointestinal AA-amyloidosis in the setting of HIV infection. Yet again, this case had concomitant Hepatitis C virus infection and intravenous/subcutaneous drug use.

Focusing on the clinical course of our index patient, it remains debatable if the lobar pneumonia had contributed to the development of the acute decline in kidney function as initially suspected. In addition to the AA-Amyloid deposits in all compartments of the renal parenchyma, a mild patchy acute tubular injury reminiscent of acute tubular necrosis was appreciated in the kidney biopsy. However, if this was the sole cause, one would have expected a much earlier recovery. Indeed, the patient never showed signs of sepsis syndrome and the respiratory symptoms together with the inflammatory markers had resolved within 1 week of the initial presentation (Fig. 2b). Instead, renal recovery had a rather protracted course, seemingly coinciding with the reduction in viral load and recovery of the CD4 count. Tuberculosis infection has been also implicated in AA-amyloid deposition. In a study conducted in South Africa, tuberculosis was present in up to 60% of biopsy samples showing AA-amyloidosis [2]. Whilst our patient had been treated for pulmonary tuberculosis 10 years previously, he had no features of active tuberculosis during the admission under discussion. Thus, we believe that the increased AA-amyloid formation was directly related to the uncontrolled HIV viraemia and the recovery in renal function was a direct response to HAART. A repeat kidney biopsy would have perhaps confirmed resorption of the AA-amyloid fibrils. However, at this point, a repeat biopsy would not have changed the patient’s management and therefore was considered unnecessary from a therapeutic perspective.

AA-amyloidosis features in less than 2% of all renal biopsies in the context of HIV infection [2, 16, 17]. However, in a study conducted by Jung et al. [18] renal AA-amyloidosis was the predominant cause of progressive CKD in up to 50% of intravenous drug users in Germany. Although HIV infection was significantly commoner in patients with AA-amyloidosis compared to patients diagnosed with other type of CKD, this study was not designed to assess causality of amyloidosis, especially in the presence of other confounding variables such as duration of intravenous drug use and frequency of bacterial infections, especially involving skin and soft tissues. Therefore, it remains unclear if the deposition of AA-amyloid in the study above was related to the chronic skin infections at the site of injection or the HIV replication itself [18]. Certainly, acute phase reactants such as serum amyloid-A levels were higher in HIV positive individuals even in the absence of intravenous drug use compared to non-users [19]. Moreover, our index case proves that AA-amyloidosis in the context of HIV infection is possible even without a history of intravenous drug abuse or chronic opportunistic infections. The seemingly low incidence of HIV related AA-amyloidosis might be related to under-diagnosis. We speculate that some HIV patients presenting with nephrotic syndrome and renal insufficiency are erroneously diagnosed with HIV associated nephropathy on clinical ground alone. Our case reinforces the importance of tissue diagnosis in HIV positive patients prior to HAART initiation.

Treatment strategies mainly revolve around targeting the underlying inflammatory condition. For instance, immunosuppressive therapy has been shown to result in stabilisation and sometimes even reversal of the amyloid deposits with improvement in renal function in certain rheumatic conditions [20–22]. In our index case, we believe that HAART has led to the resolution of proteinuria and almost complete recovery of excretory function even after a prolonged period of haemodialysis dependence. This suggests that HAART can be successfully employed to reverse advanced HIV related renal AA-amyloidosis. Multicentre collaboration and registry analysis would be beneficial to investigate outcomes in such a rare condition.

Conclusion

There are several interesting features about this case of HIV related renal AA-amyloidosis. Our patient denied any intravenous drug abuse, had no concomitant chronic infections and presented with AKI requiring haemodialysis within 2 weeks of the initial presentation. Significant improvement in proteinuria and almost complete recovery of excretory function even after 10 months of haemodialysis dependence seems to be directly related to treatment with HAART. Two years after diagnosis, the patient had almost normal excretory function with a GFR of 63 mL/min/1.73 m2.

Compliance with ethical standards

Conflict of interest

All the authors declare no competing interest in this study.

Human and animal rights

This article does not contain any studies with human participants or animals performed by any of the authors.

Informed consent

Informed consent was obtained for the publication of this case study.

Footnotes

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Lachmann HJ, Goodman HJ, Gilbertson JA, et al. Natural history and outcome in systemic AA amyloidosis. N Engl J Med. 2007;356(23):2361–2371. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa070265. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hassen M, Bates W, Moosa MR. Pattern of renal amyloidosis in South Africa. BMC Nephrol. 2019;20(1):406. doi: 10.1186/s12882-019-1601-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Merlini G, Bellotti V. Molecular mechanisms of amyloidosis. N Engl J Med. 2003;349(6):583–596. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra023144. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Papa R, Lachmann HJ. Secondary, AA, amyloidosis. Rheum Dis Clin North Am. 2018;44(4):585–603. doi: 10.1016/j.rdc.2018.06.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Gertz MA, Kyle RA. Secondary systemic amyloidosis: response and survival in 64 patients. Medicine (Baltimore) 1991;70(4):246–256. doi: 10.1097/00005792-199107000-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ozen S. Renal amyloidosis in familial Mediterranean fever. Kidney Int. 2004;65(3):1118–1127. doi: 10.1111/j.1523-1755.2004.00485.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Connolly JO, Gillmore JD, Lachmann HJ, Davenport A, Hawkins PN, Woolfson RG. Renal amyloidosis in intravenous drug users. QJM. 2006;99(11):737–742. doi: 10.1093/qjmed/hcl092. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ford E, Puronen C, Sereti I. Immunopathogenesis of asymptomatic chronic HIV Infection: the calm before the storm. Cur Opin HIV AIDS. 2009;4(3):206–214. doi: 10.1097/COH.0b013e328329c68c. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Chan-Tack K, Uche A, Greisman L, Redfield R, Ahuja N, Weinman E, et al. Acute renal failure and nephrotic range proteinuria due to amyloidosis in an HIV-infected patient. Am J Med Sci. 2006;332(6):364–367. doi: 10.1097/00000441-200612000-00012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Paiardini M, Muller-Trutwin M. HIV-associated chronic immune activation. Immunol Rev. 2013;254(1):78–101. doi: 10.1111/imr.12079. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Coelho S, Fernandes A, Soares E, Valério P, Farinha A, Natário A, Sá J. Amyloidosis related to HIV—an unusual cause of nephrotic syndrome in HIV patients. Port J Nephrol Hypert. 2017;31(3):207–211. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Cozzi PJ, Abu-Jawdeh GM, Green RM, Green D. Amyloidosis in association with human immunodeficiency virus infection. Clin Infect Dis. 1992;14(1):189–191. doi: 10.1093/clinids/14.1.189. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kurz M, Burkhalter F, Dickenmann M, Hopfer H, Mayr M, Elzi L, Battegay M. Acute kidney injury KDIGO stage 2 to 3 in HIV-positive patients treated with cART–a case series over 11 years in a cohort of 1,153 patients. Swiss Med Wkly. 2015;29(145):w14135. doi: 10.4414/smw.2015.14135. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.de Vallière S, Mary C, Joneberg JE, Rotman S, Bullani R, Greub G, Gillmore JD, Buffet PA, Tarr PE. AA-amyloidosis caused by visceral leishmaniasis in a human immunodeficiency virus-infected patient. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 2009;81(2):209–212. doi: 10.4269/ajtmh.2009.81.209. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Newey C, Odedra BJ, Standish RA, Furmali R, Edwards SG, Miller RF. Renal and gastrointestinal amyloidosis in an HIV-infected injection drug user. Int J STD AIDS. 2007;18(5):357–358. doi: 10.1258/095646207780749691. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Wyatt CM, Morgello S, Katz-Malamed R, Wei C, Klotman ME, Klotman PE, D'Agati VD. The spectrum of kidney disease in patients with AIDS in the era of antiretroviral therapy. Kidney Int. 2009;75(4):428–434. doi: 10.1038/ki.2008.604. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Nebuloni M, Barbiano di Belgiojoso G, Genderini A, Tosoni A, Riani LN, Heidempergher M, Zerbi P, Vago L. Glomerular lesions in HIV-positive patients: a 20-year biopsy experience from Northern Italy. Clin Nephrol. 2009;72(1):38–45. doi: 10.5414/cnp72038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Jung O, Haack HS, Buettner M, Betz C, Stephan C, Gruetzmacher P, Amann K, Bickel M. Renal AA-amyloidosis in intravenous drug users–a role for HIV-infection? BMC Nephrol. 2012;21(13):151. doi: 10.1186/1471-2369-13-151. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Samikkannu T, Rao KVK, Arias AY, Kalaichezian A, Sagar V, Yoo C, et al. HIV infection and drugs of abuse: role of acute phase proteins. J Neuroinflammation. 2013;10(1):113. doi: 10.1186/1742-2094-10-113. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Mpofu S, Teh LS, Smith PJ, Moots RJ, Hawkins PN. Cytostatic therapy for AA amyloidosis complicating psoriatic spondyloarthropathy. Rheumatology (Oxford) 2003;42(2):362–366. doi: 10.1093/rheumatology/keg101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Nakamura T, Yamamura Y, Tomoda K, Tsukano M, Shono M, Baba S. Efficacy of cyclophosphamide combined with prednisolone in patients with AA amyloidosis secondary to rheumatoid arthritis. Clin Rheumatol. 2003;22(6):371–375. doi: 10.1007/s10067-003-0763-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Berglund K, Thysell H, Keller C. Results, principles and pitfalls in the management of renal AA-amyloidosis; a 10–21 year follow up of 16 patients with rheumatic disease treated with alkylating cytostatics. J Rheumatol. 1993;20(12):2051–2057. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]