Dear Editor,

Corona virus disease 2019 (COVID-19) is associated with acute kidney injury (AKI) in patients that require critical care [1]. As we have previously reported, the association between clinical AKI and biomarkers was not strong, perhaps indicating less renal tissue damage [2]. Further, the preceding illness with high fever and restrictive fluid treatment in intensive care (ICU) may cause AKI through dehydration [3]. The mechanisms of AKI in COVID-19 may include direct viral injury [4]. However, urinary viral load in this cohort was low even in patients with severe AKI [5]. This study reports the prevalence of chronic kidney failure (CKD) three to 6 months after discharge in a cohort COVID-19 ICU patients. A total of 122 patients were included during their ICU stay. We excluded 3 who did not have COVID-19, 33 who died, and 26 who declined follow-up or did not have creatinine analysis. This left 60 patients analysed in the present study.

Baseline creatinine and eGFR were extracted from the medical records from the preceding year and used for CKD definition. AKI during the ICU-stay was defined according to KDIGO-criteria [6]. Kidney function at follow-up was estimated from plasma creatinine.

Data are expressed as mean ± standard deviation, median (IQR) or number of patients (%). Statistical differences were tested using Student’s t test, Wilcoxon’s Rank Sum Test or Chi-square-test as appropriate. p < 0.05 was considered significant.

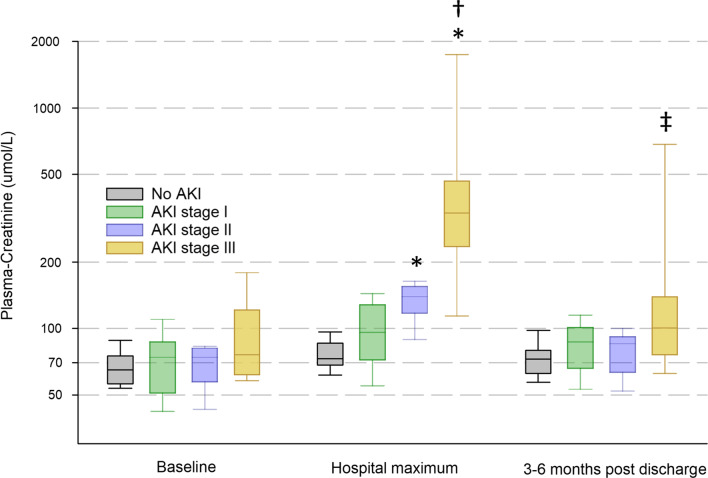

Before COVID-19 onset only six patients had CKD stage 3 or higher (Table 1). During intensive care 27 (45%) patients did not develop AKI, 19 (31%) developed stage 1, 6 (10%) stage 2, and 8 (13%) stage 3. Patients had higher maximal creatinine (p = 3.5*10–15) based on the level of AKI. This was driven by a significant increase in creatinine from baseline (p = 1.4*10–8), that was expectedly more pronounced with increasing AKI stage (p = 2.3*10–9). The increase tended to normalise at follow-up, but creatinine remained higher in patients with stage 3 AKI than those who never developed AKI during the ICU-stay (Fig. 1).

Table 1.

Patient characteristics of 60 followed-up after critial COVID-19 with kidney function three to six months after discharge. 50 patients (83%) did not progress, while 10 (17%) showed progression to a higher CKD stage. p indicates indicates probability of chance difference between patients without progression and patients with progression. Only severity of acute kidney injury (AKI) in the form of KDIGO stage 3 or dialysis, or duration of AKI in the form of acute kidney disease (AKD) were risk factors for CKD progression

| All patients | No progression | CKD progression | p | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Demographics | n = 60 | n = 50 | n = 10 | |

| Age | 60 ± 12 | 60 ± 13 | 59 ± 10 | NS |

| Women | 17(28%) | 15(30%) | 2(20%) | NS |

| BMI | 30 ± 6 | 30 ± 6 | 29 ± 6 | NS |

| Comorbidities | n (%) | |||

| Lung disease | 16(27%) | 14(28%) | 2(20%) | NS |

| Hypertension | 27(45%) | 24(48%) | 3(30%) | NS |

| Heart failure | 0 | 0 | 0 | NS |

| Ischemic heart disease | 2(3%) | 2(4%) | 0 | NS |

| Vascular disease | 4(6%) | 3(6%) | 1(10%) | NS |

| Malignancy | 2(3%) | 1(2%) | 1(10%) | NS |

| Diabetes mellitus | 12(20%) | 11(22%) | 1(10%) | NS |

| Neurological disease | 2(3%) | 2(4%) | 0 | NS |

| Psychiatric disease | 3(5%) | 3(6%) | 0 | NS |

| Current smoker | 3(5%) | 2(4%) | 1(10%) | NS |

| Kidney parameters | Mean ± SD or median (IQR) or n (%) | |||

| CKD stage ≥ 3 at baseline | 6(10%) | 6(12%) | 0 | NS |

| Baseline CKD stage | 2(1–2) | 2(2–2) | 1(1–2) | NS |

| Baseline creatinine | 77 ± 24 | 79 ± 25 | 68 ± 18 | NS |

| Baseline eGFR | 78 ± 13 | 76 ± 13 | 83 ± 11 | NS |

| Chronic dialysis at baseline | 0 | 0 | 0 | NS |

| Discharge creatinine | 94 ± 84 | 81 ± 54 | 162 ± 154 | NS |

| Discharge eGFR | 75 ± 23 | 76 ± 20 | 65 ± 35 | NS |

| Drugs at admission | n (%) | |||

| Steroid treatment | 5(8%) | 5(10%) | 0 | NS |

| ACEi/ARB | 20(33%) | 19(38%) | 1(10%) | NS |

| Anticoagulants | 6(10%) | 6(12%) | 0 | NS |

| ICU characteristics | n (%) or mean ± SD | |||

| SAPS3 at arrival | 51 ± 8 | 52 ± 8 | 49 ± 11 | NS |

| ICU Length of stay (days) | 12 ± 9 | 12 ± 9 | 13 ± 12 | NS |

| Lowest PO2/FiO2 (kPa) | 13 ± 6 | 12 ± 5 | 15 ± 12 | NS |

| Invasive ventilation (y/n) | 27(45%) | 23(46%) | 4(40%) | NS |

| Ventilator free days | 24 ± 7 | 25 ± 7 | 24 ± 10 | NS |

| Mild ARDS | 1(2%) | 1(2%) | 0 | NS |

| Moderate ARDS | 2(3%) | 2(4%) | 0 | NS |

| Severe ARDS | 28(47%) | 23(46) | 5(50%) | NS |

| Vasopressor (y/n) | 36(60%) | 29(58%) | 7(70%) | NS |

| Vasopressor free days | 26 ± 6 | 26 ± 6 | 25 ± 5 | NS |

| AKI (y/n) | 33(55%) | 26(52%) | 7(70%) | NS |

| Severe AKI (stage 3) | 9(15%) | 5(10%) | 4(40%) | 0.016 |

| Acute kidney disease (y/n) | 14(23%) | 5(10%) | 9(90%) | 0.019 |

| Dialysis in ICU (y/n) | 6(10%) | 3(6%) | 3(30%) | 0.02 |

| Dialysis free days | 29 ± 3 | 29 ± 3 | 28 ± 3 | NS |

| Chronic dialysis at follow-up | 1(1.7%) | 0 | 1(10%) | NS |

ACEi angiotensin converting enzyme inhibitor, AKI acute kidney injury, ARB angiotensin II receptor blocker, ARDS acute respiratory distress syndrome, BMI Body mass index, CKD chronic kidney disease, eGFR estimated GFR, ICU intensive care unit, IQR interquartile range, SAPS3 simplified acute physiology score-3, SD standard deviation

Fig. 1.

Progression of plasma creatinine in patients who developed different stages of AKI (No AKI n = 27, Stage 1 n = 19, Stage 2 n = 6, Stage 3 n = 8) during their ICU stay. A mixed model ANOVA on the logarithm of the concentration showed a significant difference in creatinine between stages (p = 3.5*10–15), as well as time-points (p = 1.4*10–8), with a highly significant interaction (p = 2.3*10–9). *Indicates significant difference compared to patients who did not develop AKI, †Compared to baseline for the same stage, and ‡compared to hospital maximum for the same stage by TukeyHSD

Average follow-up time was 18 ± 3 weeks after discharge (range 10 to 26 weeks). Ten patients progressed to a higher CKD stage at follow-up than before contracting COVID-19. Patients with KDIGO stage 3 were more likely to progress to a higher CKD stage (Odds ratio 4.9[1.4–31], p = 0.009). Acute kidney disease (AKD) defined as AKI lasting for more than 7 days was associated with progression of CKD (Odds ratio 3.9[1.2–21], p = 0.018). There were no other statistical differences between patients who showed CKD progression compared to those that did not with regards to basic demographics, comorbid disease or ICU admission characteristics (Table 1). It should be noted that sarcopenia after critical care would tend to lower creatinine and may lead to over estimation of GFR, and therefore the number of patients with CKD progression may be higher than estimated in this dataset.

The main strength of this study is its comprehensive characterisation of clinical parameters during intensive care as well as comorbid disease. The main limitations of the present dataset are the use of a CKD definition at baseline that depends on creatinine only, a relatively low number of patients leading to few endpoints, and loss to follow-up of 25% of patients without convalescent creatinine.

In conclusion, critical COVID-19 goes with progression of chronic kidney disease in a substantial number of patients. Progression in CKD grade was associated with AKD defined as more than 7 days of AKI, and with KDIGO stage 3 AKI during intensive care.

Acknowledgements

The authors thank research nurses Joanna Wessbergh and Elin Söderman, and the biobank assistants Erik Danielsson and Philip Karlsson for their expertise in compiling the study.

Authors’ contributions

All authors participated in conception and design of the study. EW and IML met patients during follow-up and collected samples. All authors had access to the data and participated in data collection and interpretation. MH drafted the manuscript, and all authors contributed to manuscript revision. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Funding

Open Access funding provided by Uppsala University. The study was funded by the SciLifeLab/KAW national COVID-19 research program Project Grant to MH (KAW 2020.0182), Swedish Society of Medicine to MH (SLS-938101), and the Swedish Research Council to RF (2014-02569 and 2014-07606).

Availability of data and materials

The datasets in the current study is available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

The presented data is part of a study approved by the National Ethical Review Agency (EPM; No. 2020-01623 and No. 2020-0362). Informed consent was obtained from the patient, or next of kin if the patient was unable to give consent during the ICU-stay, all included patients gave consent to participate in the follow-up study. The study was registered à priori (clinicaltrials.gov: https://clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/show/NCT04474249).

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

All authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Goyal P, Choi JJ, Pinheiro LC, Schenck EJ, Chen R, Jabri A, Satlin MJ, Campion TR, Jr, Nahid M, Ringel JB, et al. Clinical characteristics of Covid-19 in New York City. N Engl J Med. 2020;382(24):2372–2374. doi: 10.1056/NEJMc2010419. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Luther T, Bulow-Anderberg S, Larsson A, Rubertsson S, Lipcsey M, Frithiof R, Hultstrom M. COVID-19 patients in intensive care develop predominantly oliguric acute kidney injury. Acta Anaesthesiol Scand. 2020 doi: 10.1111/aas.13746. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hultstrom M, von Seth M, Frithiof R. Hyperreninemia and low total body water may contribute to acute kidney injury in COVID-19 patients in intensive care. J Hypertens. 2020;38(8):1613–1614. doi: 10.1097/HJH.0000000000002531. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Nadim MK, Forni LG, Mehta RL, Connor MJ, Jr, Liu KD, Ostermann M, Rimmele T, Zarbock A, Bell S, Bihorac A, et al. COVID-19-associated acute kidney injury: consensus report of the 25th Acute Disease Quality Initiative (ADQI) Workgroup. Nat Rev Nephrol. 2020;16(12):747–764. doi: 10.1038/s41581-020-00356-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Frithiof R, Bergqvist A, Jarhult JD, Lipcsey M, Hultstrom M. Presence of SARS-CoV-2 in urine is rare and not associated with acute kidney injury in critically ill COVID-19 patients. Crit Care. 2020;24(1):587. doi: 10.1186/s13054-020-03302-w. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kidney Disease: Improving Global Outcomes (KDIGO) acute kidney injury work group KDIGO clinical practice guideline for acute kidney injury. Kidney Int Suppl. 2012;2:1–138. doi: 10.1038/kisup.2012.1. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

The datasets in the current study is available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.