Abstract

To identify the common and specific structural basis of bipolar depression (BD) and unipolar depression (UD) is crucial for clinical diagnosis. In this study, a total of 85 participants, including 22 BD patients, 36 UD patients, and 27 healthy controls, were enrolled. A voxel-based morphology method was used to identify the common and specific changes of the gray matter volume (GMV) to determine the structural basis. Significant differences in GMV were found among the three groups. Compared with healthy controls, UD patients showed decreased GMV in the orbital part of the left inferior frontal gyrus, whereas BD patients showed decreased GMV in the orbital part of the left middle frontal gyrus. Compared with BD, UD patients have increased GMV in the left supramarginal gyrus and middle temporal gyrus. Our results revealed different structural changes in UD and BD patients suggesting BD and UD have different neurophysiological underpinnings. Our study contributes toward the biological determination of morphometric changes, which could help to discriminate between UD and BD.

Keywords: bipolar disorder, unipolar depression, gray matter volume, voxel-based morphology, structural MRI

Introduction

Bipolar and unipolar depression (BD and UD) are leading causes of disability worldwide in view of the often recurrent pattern of illness, which significantly impinges on the quality of life of affected individuals (Delvecchio et al., 2012). UD and BD are both characterized by depressive symptoms, lack of interest, and loss of pleasure. Previous studies have found that 7–52% of UD patients with an initial diagnosis of BD and 0.5–1% of UD patients are converted to BD each year (Jiang et al., 2020). Until now, mental illness is diagnosed primarily through a careful assessment of behavior and subjective reports of abnormal experiences to categorize patients (Phillips and Kupfer, 2013). This means that it is difficult for clinicians to distinguish the two disorders based solely on clinical manifestations (Chen et al., 2018). The high rate of misdiagnosis can lead to a poor prognosis (Yu et al., 2020). Many researchers are seeking objective and reliable biomarkers that can differentiate between UD and BD patients. The development of neuroimaging techniques provides an opportunity to identify UD and BD and to deepen our understanding of the underlying mechanisms of affective disorders.

Neuroimaging techniques have received growing attention for studying brain alterations in affective disorders, which are associated with structural and functional abnormalities of the brain (Bremner et al., 2002; Wu et al., 2016, 2017; Wang et al., 2018, 2019b, 2020; Andreou and Borgwardt, 2020). Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) is a non-invasive method to characterize the brain structure and function in vivo (Abe et al., 2010; Takamura and Hanakawa, 2017; Wang et al., 2019a). Voxel-based morphometry (VBM) is a widely used method to quantitatively detect the density and volume of brain tissue at the voxel-based level, which can reflect the differences in brain tissue composition and characteristics of individuals with BD and UD (Arnone et al., 2012, 2016, 2018; Selvaraj et al., 2012). Several studies using VBM have revealed alterations in the gray matter volume (GMV) in various brain regions in UD and BD patients compared with healthy controls (HCs) (Kandilarova et al., 2019). For example, there is reduced GMV in the prefrontal cortex (PFC), anterior cingulate cortex (ACC), hippocampus (Han et al., 2019), and amygdala (Wang et al., 2017; Calvo et al., 2019) in patients with major depressive disorder. In contrast, GMV is reduced primarily in the PFC, anterior cingulate cortex, insular cortex (Bora et al., 2010), temporal regions (Farrow et al., 2005), and orbitofrontal cortex (Eker et al., 2014) in BD patients. A meta-analysis of VBM study on UD and BD reported that GMV in the left parahippocampal gyrus and right dorsolateral PFC was significantly greater in UD patients than BD patients (Wise et al., 2017). In addition, compared with UD patients, BD patients showed reduced GMV in the right inferior frontal gyrus, middle cingulate gyrus, hippocampus, and amygdala (Bai et al., 2020). Although the previous studies have reported the structural changes in BD and UD patients, the common and specific changes in GMV in the same study remain unclear.

In this study, we recruited medication-free patients with UD and BD disorders, currently experiencing a major depressive episode. The study aimed to investigate morphometric changes in these two conditions in view of the paucity of studies directly comparing UD with BD in the same mood state and the difficulty in recruiting medication-free individuals with mood disorders (Wise et al., 2016a). Based on the findings of previous studies, we hypothesized that both BD and UD patients might show decreased GMV in PFC compared with HCs, and BD patients show decreased GMV in temporal and parietal lobes compared with UD.

Materials and Methods

Participants

The Ethical Committee of the First Hospital of Shanxi Medical University (20091217), Shanxi, China, approved the study. A full written and verbal explanation of the study was provided before enrollment, and each participant was provided written consent. We recruited the first-episode patients, including 22 type I BD patients and 36 UD patients from the First Hospital of Shanxi Medical University between December 2018 and July 2019. BD participants were included if they were medication-free and presented for the first time with a depressive episode and having experienced a previous manic episode, met criteria for bipolar disorder according to the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, Fourth Edition (DSM-IV). The UD patients were included if they were medication-free and had never experienced a previous manic episode based on the diagnosis criterion of DSM-IV. The 27 HCs were recruited by advertisement. All of the participants were right-handed, according to their accounts. Two experienced psychiatrists diagnosed BD and UD according to the Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-IV criteria. The reliability coefficient of the two assessors is 0.935, and the reliability coefficient for each subitem ranges from 0.85 to 1. All the HCs were screened using the Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-IV Non-Patient Edition to confirm the lifetime absence of illness by a clinical doctor (AZ) who is one of the coauthors. For each patient, the depressive states in both BD and UD participants were evaluated based on the 24-item Hamilton Rating Scale for Depression (HAMD-24) (Williams, 1988). The anxiety states were evaluated based on the Hamilton Anxiety Scale (HAMA) (Hamilton, 1959), and the manic states were evaluated based on the Young Mania Rating Scale (YMRS) (Young et al., 1978). Inclusion criteria for BD and UD patients were as follows: (1) aged from 18 to 55 years old; (2) UD and BD patients were a total HAMD-24 score > 20, and BD patients were a total YMRS score < 7; (3) without other Axis-I and Axis-II psychiatric disorders (except for UD, BD, and anxiety disorders); (4) without a history of organic brain disorders, neurological disorders, cardiovascular diseases, alcohol/substance abuse or dependence, pregnancy, or any physical illness; (5) no electroconvulsive therapy before participating in the study; (6) UD had no family history of BD; and (7) qualified to undergo an MRI. All patients were either medication-naïve or had not been taking medication for at least 6 months at the scan time. Among all the patients, two MD patients were self-administered zopiclone 6 months ago, which has been discontinued for 6 months, whereas the remaining 56 patients were not treated. The inclusion criteria for the HC group were as follows: (1) aged from 18 to 55 years old; (2) without any present or past significant medical or neurological illness; (3) without history of psychiatric illness in first-degree relatives; (4) without history of head injury; and (5) qualified to undergo an MRI.

Image Acquisition

All participants underwent MRI scanning using a MAGNETOM Trio Tim 3.0 T system (Siemens Medical Solutions, Germany) equipped with a 32-channel head coil at the Shanxi Provincial People’s Hospital in Taiyuan. None of the participants, identified by two experienced radiologists as having significant brain abnormalities, was excluded from the study. During the scan, all participants were asked to relax with their eyes closed but to remain awake. Using 3D-FLASH sequence, a high-resolution T1-weighted MRI image was acquired with the parameters as follows: repetition time = 2,300 ms, echo time = 2.95 ms, FOV = 225 × 240 mm, matrix = 240 × 256 mm, flip angle = 9°, and voxel size = 0.9375 × 0.9375 × 1.2 mm3.

Voxel-Based Morphometry

To examine differences in GMV among the three groups, VBM analysis was performed using SPM81 and VBM82 toolkits. First, all T1-weighted images were corrected for bias-field inhomogeneity and then segmented into gray matter (GM), white matter, and cerebrospinal fluid. After segmentation, the GM maps were registered into the MNI space using both linear and non-linear affine transformations. Finally, the normalized GM images were smoothed with a Gaussian kernel of 8 mm full width at half maximum for statistical analyses.

Statistical Analyses

The demographic and clinical characteristics among the UD, BD, and HC groups were compared using SPSS 22.0 version. A one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) was used to compare the age and years of education for the three groups. The χ2se-test was used to compare the sex differences among the groups. Statistical significance was set at p < 0.05.

Whole-brain VBM maps of the three groups were compared by ANOVA with total brain volume and sex information as covariates to identify abnormalities among the three groups, and post hoc two samples t-tests with total brain volume and sex information as covariates were used to identify differences between each pair of groups. The significant level was determined using the AlphaSim correction method with voxel level P < 0.001 and cluster level P < 0.05. Moreover, the average GMV values of brain areas with changed GMV were extracted, and the correlation analyses between the GMV values and the clinical performances of the UD group and BD group were calculated. The significant level was set at P < 0.05 with Bonferroni correction.

Results

Demographic and Clinical Comparisons

There was no statistical difference in age, sex, or years of education among the three groups (All P > 0.05). Moreover, there was no statistical difference in the HAMD-24, HAMA, and YMRS scores between the BD and UD groups (Table 1).

TABLE 1.

Demographic and clinical characteristics of all the participants.

| UD group (n = 36) | BD-I group (n = 22) | HC group (n = 27) | Statistical value | P-value | |

| Sex (M/F) | 16/20 | 11/11 | 13/14 | 0.188 | 0.910a |

| Age (years) | 34.11 ± 10.39 | 35.17 ± 9.98 | 32.44 ± 8.57 | 0.802 | 0.436b |

| Duration of disease (month) | 10.19 ± 5.28 | 11.14 ± 4.5 | 0.7 | 0.49 | |

| Education (years) | 12.38 ± 3.25 | 12.10 ± 3.37 | 13.96 ± 3.24 | 2.238 | 0.079b |

| HAMD-24 scores | 25.52 ± 4.27 | 24.45 ± 3.52 | N/A | 1.424 | 0.164c |

| HAMA scores | 17.76 ± 5.70 | 17.18 ± 3.82 | N/A | 0.309 | 0.759c |

| YMRS scores | 1.81 ± 0.82 | 2.10 ± 0.67 | N/A | 0.102 | 0.253c |

UD, unipolar depression; BD-I, type I bipolar depression; HC, healthy control; HAMD-24, 24-item Hamilton Depression Rating Scale; HAMA, Hamilton Anxiety Scale; YMRS, Young Mania Rating Scale; M, male; F, female; N/A, not applicable.

achi-square test; bone-way ANOVA; ctwo-sample t-test.

Voxel-Based Morphometry Analysis

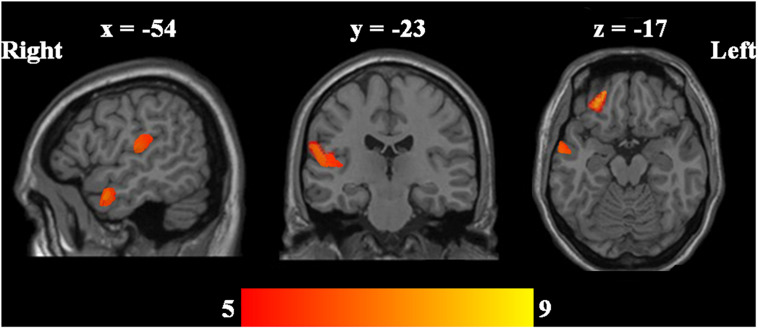

Using ANOVA, the regional GMV in the left middle temporal gyrus, orbital part of the left middle frontal gyrus, orbital part of the left inferior frontal gyrus, and left supramarginal gyrus showed significant differences among the three groups (Table 2 and Figure 1).

TABLE 2.

Regional GMV differences between UD groups, BD groups and HC groups.

| Brain areas | Cluster size | BA | L/R | MNI coordinates |

F-value |

||

| x | y | z | (peak) | ||||

| Differences among three groups | |||||||

| Middle temporal gyrus | 245 | 21 | L | −59 | 2 | −20 | 7.807 |

| Orbital part of the inferior frontal gyrus | 401 | 11/47 | L | −27 | 42 | −17 | 7.774 |

| Supramarginal gyrus | 450 | 40 | L | −54 | −23 | 13 | 7.344 |

| UD > BD | |||||||

| Supramarginal gyrus | 484 | 40 | L | −54 | −21 | 15 | 3.295 |

| BD < HC | |||||||

| Orbital part of the middle frontal gyrus | 156 | 10, 10 | L | −24 | 56 | 10 | −3.351 |

| UD < HC | |||||||

| Orbital part of inferior frontal gyrus | 299 | 11, 11, and 47 | L | −27 | 42 | −15 | −3.325 |

BA, brodmann area; MNI, montreal neurological institute; L/R, left/right hemisphere.

FIGURE 1.

ANOVA was performed to determine whether there are GMV differences among UD, BD, and HCs. Significant level was defined using AlphaSim correction P < 0.05 with voxel-level P < 0.001.

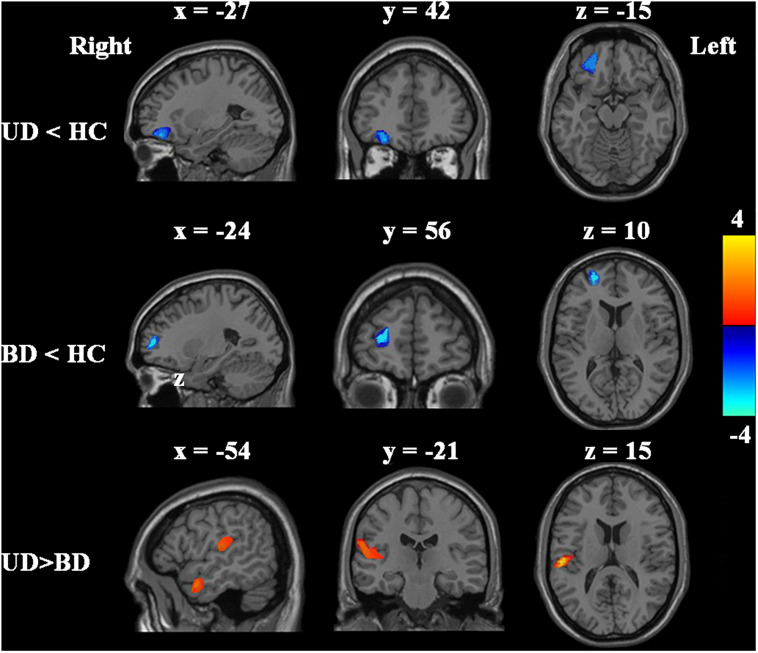

Compared with HCs, the UD patients showed significantly decreased GMV in the orbital part of the left inferior frontal gyrus, whereas BD patients showed significantly decreased GMV in the orbital part of the left middle frontal gyrus (Table 2 and Figure 2). Compared with BD patients, UD had increased GMV in the left supramarginal gyrus and middle temporal gyrus (Table 2 and Figure 2).

FIGURE 2.

Post hoc two-sample t-tests were performed to identify GMV differences between UD, BD, and HCs groups. Significant level was determined using AlphaSim correction P < 0.05 with voxel-level P < 0.001.

Associations Between the Altered Gray Matter Volume and Clinical Characteristics

In the UD and BD groups, Pearson’s correlation analyses were performed between the altered GMV and the HAMD-24 and YMRS scores. There were no significant associations between the GMV and HAMD-24 (r = 0.17 and P > 0.05) or YMRS (r = 0.23 and P > 0.05).

Discussion

In this study, we reported that patients with mood disorders (UD and BD) showed specific GMV differences in the left middle temporal gyrus, orbital part of the middle frontal gyrus, inferior frontal gyrus, and supramarginal gyrus. These findings were consistent with the reports by previous studies (Yang et al., 2017; Kandilarova et al., 2019). The previous studies of UD or BD patients demonstrated reduced GMV in the amygdala, ventral striatum, posterior cingulate cortex, hippocampus, parahippocampal cortex, superior temporal gyrus, and temporopolar cortex (Drevets, 2007; Wang et al., 2017). A previous study about UD found reduced GMV in the temporal lobe regions, especially in the superior temporal gyrus (Ma et al., 2012). Additionally, in young and middle-aged patients with a familial risk of depression, the subjects have a thinner cortex than HCs in the extrahippocampal medial temporal lobe and other brain regions (Peterson et al., 2009). In BD patients, smaller volume and less gray matter densities in the left ventromedial temporal lobe, thinner cingulate, and orbital cortex were found compared with HCs, and changed cortical thickness was associated with abnormal autonomic response to emotional stimuli (Lochhead et al., 2004; Lyoo et al., 2006). All these findings suggested that structural changes may be the neuropathological basis and a neural marker to distinguish the UD and BD patients (Donix et al., 2018).

Gray matter volume differences between UD and BD have been reported in a previous study that found significantly less GMV in the hippocampal formation, insula, and temporal pole in patients with BD than in patients with UD (Redlich et al., 2014). Moreover, Versace et al. (2010) reported that BD showed less fractional anisotropy in the left superior longitudinal fasciculus of the supramarginal gyrus and left posterior cingulum than those with UD (Wise et al., 2016b). In addition, bipolar I disorder patients showed decreased activation in the middle temporal gyrus compared with UD patients (Cerullo et al., 2014). In our study, we further revealed that patients with BD had decreased GMV in the left supramarginal gyrus and middle temporal gyrus than UD patients. Considering these regions play an important role in emotion processing and regulation, we speculated that the above brain regions with structural and functional changes may be the neuroanatomical basis of clinical symptoms of UD and BD. However, we found that the altered GMV was not associated with HAMD-24 scores, suggesting that this difference may be related to the disease itself but not to its clinical symptoms. This is just a speculative explanation and cannot rule out that the clinical symptoms caused by the altered brain regions of UD and BD groups not reflected in the HAMD-24 scores. Therefore, it is necessary to expand the sample size for further research and exploration.

Prefrontal cortex is a complex structure whose main function is related to control emotion, attention, reward processing, and response inhibition (Cerullo et al., 2009). The orbital part of the PFC is located in the rostral frontal lobe. The orbital part of the PFC is involved in learning, memory, higher cognitive function, emotional regulation, and psychiatric disorders (Downar, 2019). Our results showed that UD and BD patients had less GMV in the orbital part of the left middle frontal gyrus and inferior frontal gyrus compared with HCs. This finding was supported by the previous structural and meta-analysis studies that reported decreased cortical thickness and decreased functional activities in UD and BD patients (Fitzgerald et al., 2008; Lim et al., 2013; Han et al., 2014; Abe et al., 2015; Fung et al., 2015). All the results demonstrated that both BD and UD patients have structural changes in the orbital part of the PFC, which may be associated with abnormalities in emotional and cognitive functions.

There are some limitations to this study. First, our study only includes a small sample, and all these findings need to be replicated in larger sample size and a wider range of symptoms to further confirm the experimental results. Second, children and the elderly were not included in the study to exclude the influence of immature children and physical diseases of the elderly on the results. Third, because of some UD and BD patients with high HAMA scores, this may affect our current findings. Fourth, we did not measure the IQ for patients; whether IQ affects the findings needs to be further validated. Finally, a long-term follow-up study is needed to determine whether UD patients convert to BD.

In conclusion, we revealed specific brain structural abnormalities in BD and UD patients using VBM analyses. These findings provided us with the opportunities to identify UD and BD and to gain knowledge of the neural underpinning of affective disorders. The specific differences in GMV found between BD and UD may serve as effective biomarkers to distinguish UD from BD in the future.

Data Availability Statement

The raw data supporting the conclusions of this article will be made available by the authors, without undue reservation.

Ethics Statement

The studies involving human participants were reviewed and approved by the First Hospital of Shanxi Medical University. The patients/participants provided their written informed consent to participate in this study.

Author Contributions

YX and NS designed the experiments. JW, PL, JW, AZ, SL, and CY performed the clinical data collection and assessment. JW and PL performed the neuroimaging data analysis and wrote the draft. All the authors discussed the results and reviewed the manuscript.

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Funding. This study was supported by the National Natural Science Youth Fund Project (81601192 and 81701345), National Natural Science Foundation of China (81971601), National Key Research And Development Program of China (2016YFC1307103), Research Project supported by Shanxi Scholarship Council of China (HGKY2019098), 136 Medical Rejuvenation Project of Shanxi Province, Program of the Youth Sanjin Scholars, and Program for the Outstanding Innovative Teams of Higher Learning Institutions of Shanxi.

References

- Abe C., Ekman C. J., Sellgren C., Petrovic P., Ingvar M., Landen M. (2015). Manic episodes are related to changes in frontal cortex: a longitudinal neuroimaging study of bipolar disorder 1. Brain 138 3440–3448. 10.1093/brain/awv266 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Abe O., Yamasue H., Kasai K., Yamada H., Aoki S., Inoue H., et al. (2010). Voxel-based analyses of gray/white matter volume and diffusion tensor data in major depression. Psychiatry Res. 181 64–70. 10.1016/j.pscychresns.2009.07.007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Andreou C., Borgwardt S. (2020). Structural and functional imaging markers for susceptibility to psychosis. Mol. Psychiatry 25 2773–2785. 10.1038/s41380-020-0679-7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arnone D., Cavanagh J., Gerber D., Lawrie S. M., Ebmeier K. P., McIntosh A. M. (2018). Magnetic resonance imaging studies in bipolar disorder and schizophrenia: meta-analysis. Br. J. Psychiatry 195 194–201. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arnone D., Job D., Selvaraj S., Abe O., Amico F., Cheng Y., et al. (2016). Computational meta-analysis of statistical parametric maps in major depression. Hum. Brain Mapp. 37 1393–1404. 10.1002/hbm.23108 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arnone D., McIntosh A. M., Ebmeier K. P., Munafò M. R., Anderson I. M. (2012). Magnetic resonance imaging studies in unipolar depression: systematic review and meta-regression analyses. Eur. Neuropsychopharmacol. 22 1–16. 10.1016/j.euroneuro.2011.05.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bai Y. M., Chen M. H., Hsu J. W., Huang K. L., Tu P. C., Chang W. C., et al. (2020). A comparison study of metabolic profiles, immunity, and brain gray matter volumes between patients with bipolar disorder and depressive disorder. J. Neuroinflammation 17:42. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bora E., Fornito A., Yucel M., Pantelis C. (2010). Voxelwise meta-analysis of gray matter abnormalities in bipolar disorder. Biol. Psychiatry 67 1097–1105. 10.1016/j.biopsych.2010.01.020 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bremner J. D., Vythilingam M., Vermetten E., Nazeer A., Adil J., Khan S., et al. (2002). Reduced volume of orbitofrontal cortex in major depression. Biol. Psychiatry 51 273–279. 10.1016/s0006-3223(01)01336-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Calvo A., Delvecchio G., Altamura A. C., Soares J. C., Brambilla P. (2019). Gray matter differences between affective and non-affective first episode psychosis: a review of Magnetic Resonance Imaging studies: Special Section on “Translational and Neuroscience Studies in Affective Disorders” Section Editor, Maria Nobile MD, PhD. This Section of JAD focuses on the relevance of translational and neuroscience studies in providing a better understanding of the neural basis of affective disorders. The main aim is to briefly summaries relevant research findings in clinical neuroscience with particular regards to specific innovative topics in mood and anxiety disorders. J. Affect. Disord. 243 564–574. 10.1016/j.jad.2018.03.008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cerullo M. A., Adler C. M., Delbello M. P., Strakowski S. M. (2009). The functional neuroanatomy of bipolar disorder. Int. Rev. Psychiatry 21 314–322. 10.1080/09540260902962107 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cerullo M. A., Eliassen J. C., Smith C. T., Fleck D. E., Nelson E. B., Strawn J. R., et al. (2014). Bipolar I disorder and major depressive disorder show similar brain activation during depression. Bipolar Disord. 16 703–712. 10.1111/bdi.12225 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen L., Wang Y., Niu C., Zhong S., Hu H., Chen P., et al. (2018). Common and distinct abnormal frontal-limbic system structural and functional patterns in patients with major depression and bipolar disorder. NeuroImage Clin. 20 42–50. 10.1016/j.nicl.2018.07.002 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Delvecchio G., Fossati P., Boyer P., Brambilla P., Falkai P., Gruber O., et al. (2012). Common and distinct neural correlates of emotional processing in Bipolar Disorder and Major Depressive Disorder: a voxel-based meta-analysis of functional magnetic resonance imaging studies. Eur. Neuropsychopharmacol. J. Eur. Coll. Neuropsychopharmacol. 22 100–113. 10.1016/j.euroneuro.2011.07.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Donix M., Haussmann R., Helling F., Zweiniger A., Lange J., Werner A., et al. (2018). Cognitive impairment and medial temporal lobe structure in young adults with a depressive episode. J. Affect. Disord. 237 112–117. 10.1016/j.jad.2018.05.015 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Downar J. (2019). Orbitofrontal cortex: a ‘non-rewarding’ new treatment target in depression? Curr. Biol. 29 R59–R62. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Drevets W. C. (2007). Orbitofrontal cortex function and structure in depression. Ann. N. Y. Acad. Sci. 1121 499–527. 10.1196/annals.1401.029 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eker C., Simsek F., Yilmazer E. E., Kitis O., Cinar C., Eker O. D., et al. (2014). Brain regions associated with risk and resistance for bipolar I disorder: a voxel-based MRI study of patients with bipolar disorder and their healthy siblings. Bipolar Disord. 16 249–261. 10.1111/bdi.12181 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Farrow T. F., Whitford T. J., Williams L. M., Gomes L., Harris A. W. (2005). Diagnosis-related regional gray matter loss over two years in first episode schizophrenia and bipolar disorder. Biol. Psychiatry 58 713–723. 10.1016/j.biopsych.2005.04.033 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fitzgerald P. B., Laird A. R., Maller J., Daskalakis Z. J. (2008). A meta-analytic study of changes in brain activation in depression. Hum. Brain Mapp. 29 683–695. 10.1002/hbm.20426 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fung G., Deng Y., Zhao Q., Li Z., Qu M., Li K., et al. (2015). Distinguishing bipolar and major depressive disorders by brain structural morphometry: a pilot study. BMC Psychiatry 15:298. 10.1186/s12888-015-0685-5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hamilton M. (1959). The assessment of anxiety states by rating. Br. J. Med. Psychol. 32 50–55. 10.1111/j.2044-8341.1959.tb00467.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Han K. M., Choi S., Jung J., Na K. S., Yoon H. K., Lee M. S., et al. (2014). Cortical thickness, cortical and subcortical volume, and white matter integrity in patients with their first episode of major depression. J. Affect. Disord. 155 42–48. 10.1016/j.jad.2013.10.021 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Han K. M., De Berardis D., Fornaro M., Kim Y. K. (2019). Differentiating between bipolar and unipolar depression in functional and structural MRI studies. Prog. Neuropsychopharmacol. Biol. Psychiatry 91 20–27. 10.1016/j.pnpbp.2018.03.022 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jiang X., Fu S., Yin Z., Kang J., Wang X., Zhou Y., et al. (2020). Common and distinct neural activities in frontoparietal network in first-episode bipolar disorder and major depressive disorder: preliminary findings from a follow-up resting state fMRI study. J. Affect. Disord. 260 653–659. 10.1016/j.jad.2019.09.063 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kandilarova S., Stoyanov D., Sirakov N., Maes M., Specht K. (2019). Reduced grey matter volume in frontal and temporal areas in depression: contributions from voxel-based morphometry study. Acta Neuropsychiatr. 31 252–257. 10.1017/neu.2019.20 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lim C. S., Baldessarini R. J., Vieta E., Yucel M., Bora E., Sim K. (2013). Longitudinal neuroimaging and neuropsychological changes in bipolar disorder patients: review of the evidence. Neurosci. Biobehav. Rev. 37 418–435. 10.1016/j.neubiorev.2013.01.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lochhead R. A., Parsey R. V., Oquendo M. A., Mann J. J. (2004). Regional brain gray matter volume differences in patients with bipolar disorder as assessed by optimized voxel-based morphometry. Biol. Psychiatry 55 1154–1162. 10.1016/j.biopsych.2004.02.026 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lyoo I. K., Sung Y. H., Dager S. R., Friedman S. D., Lee J. Y., Kim S. J., et al. (2006). Regional cerebral cortical thinning in bipolar disorder. Bipolar Disord. 8 65–74. 10.1111/j.1399-5618.2006.00284.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ma C., Ding J., Li J., Guo W., Long Z., Liu F., et al. (2012). Resting-state functional connectivity bias of middle temporal gyrus and caudate with altered gray matter volume in major depression. PLoS One 7:e45263. 10.1371/journal.pone.0045263 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peterson B. S., Warner V., Bansal R., Zhu H., Hao X., Liu J., et al. (2009). Cortical thinning in persons at increased familial risk for major depression. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 106 6273–6278. 10.1073/pnas.0805311106 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Phillips M. L., Kupfer D. J. (2013). Bipolar disorder diagnosis: challenges and future directions. Lancet 381 1663–1671. 10.1016/s0140-6736(13)60989-7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Redlich R., Almeida J. J., Grotegerd D., Opel N., Kugel H., Heindel W., et al. (2014). Brain morphometric biomarkers distinguishing unipolar and bipolar depression. A voxel-based morphometry-pattern classification approach. JAMA Psychiatry 71 1222–1230. 10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2014.1100 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Selvaraj S., Arnone D., Job D., Stanfield A., Farrow T. F., Nugent A. C., et al. (2012). Grey matter differences in bipolar disorder: a meta-analysis of voxel-based morphometry studies. Bipolar Disord. 14 135–145. 10.1111/j.1399-5618.2012.01000.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Takamura T., Hanakawa T. (2017). Clinical utility of resting-state functional connectivity magnetic resonance imaging for mood and cognitive disorders. J. Neural Transm. 124 821–839. 10.1007/s00702-017-1710-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Versace A., Almeida J. R., Quevedo K., Thompson W. K., Terwilliger R. A., Hassel S., et al. (2010). Right orbitofrontal corticolimbic and left corticocortical white matter connectivity differentiate bipolar and unipolar depression. Biol. Psychiatry 68 560–567. 10.1016/j.biopsych.2010.04.036 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang J., Becker B., Wang L., Li H., Zhao X., Jiang T. (2019a). Corresponding anatomical and coactivation architecture of the human precuneus showing similar connectivity patterns with macaques. NeuroImage 200 562–574. 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2019.07.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang J., Ji Y., Li X., He Z., Wei Q., Bai T., et al. (2020). Improved and residual functional abnormalities in major depressive disorder after electroconvulsive therapy. Prog. Neuropsychopharmacol. Biol. Psychiatry 100:109888 10.1016/j.pnpbp.2020.109888 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang J., Wei Q., Bai T., Zhou X., Sun H., Becker B., et al. (2017). Electroconvulsive therapy selectively enhanced feedforward connectivity from fusiform face area to amygdala in major depressive disorder. Soc. cogn. Affect. Neurosci. 12 1983–1992. 10.1093/scan/nsx100 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang J., Wei Q., Wang L., Zhang H., Bai T., Cheng L., et al. (2018). Functional reorganization of intra- and internetwork connectivity in major depressive disorder after electroconvulsive therapy. Hum. Brain Mapp. 39 1403–1411. 10.1002/hbm.23928 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang L., Wei Q., Wang C., Xu J., Wang K., Tian Y., et al. (2019b). Altered functional connectivity patterns of insular subregions in major depressive disorder after electroconvulsive therapy. Brain Imaging Behav. 14 753–761. 10.1007/s11682-018-0013-z [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Williams J. B. (1988). A structured interview guide for the Hamilton Depression Rating Scale. Arch. Gen. Psychiatry 45 742–747. 10.1001/archpsyc.1988.01800320058007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wise T., Arnone D., Marwood L., Zahn R., Lythe K. E., Young A. H. (2016a). Recruiting for research studies using online public advertisements: examples from research in affective disorders. Neuropsychiatr. Dis. Treat 12 279–285. 10.2147/ndt.s90941 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wise T., Radua J., Nortje G., Cleare A. J., Young A. H., Arnone D. (2016b). Voxel-based meta-analytical evidence of structural disconnectivity in major depression and bipolar disorder. Biol. Psychiatry 79 293–302. 10.1016/j.biopsych.2015.03.004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wise T., Radua J., Via E., Cardoner N., Abe O., Adams T. M., et al. (2017). Common and distinct patterns of grey-matter volume alteration in major depression and bipolar disorder: evidence from voxel-based meta-analysis. Mol. Psychiatry 22 1455–1463. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu H., Sun H., Wang C., Yu L., Li Y., Peng H., et al. (2017). Abnormalities in the structural covariance of emotion regulation networks in major depressive disorder. J. Psychiatr. Res. 84 237–242. 10.1016/j.jpsychires.2016.10.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu H., Sun H., Xu J., Wu Y., Wang C., Xiao J., et al. (2016). Changed hub and corresponding functional connectivity of subgenual anterior cingulate cortex in major depressive disorder. Front. Neuroanat. 10:120. 10.3389/fnana.2016.00120 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang X., Peng Z., Ma X., Meng Y., Li M., Zhang J., et al. (2017). Sex differences in the clinical characteristics and brain gray matter volume alterations in unmedicated patients with major depressive disorder. Sci. Rep. 7:2515. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Young R. C., Biggs J. T., Ziegler V. E., Meyer D. A. (1978). A rating scale for mania: reliability, validity and sensitivity. Br. J. Psychiatry J. Ment. Sci. 133 429–435. 10.1192/bjp.133.5.429 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yu Z., Qin J., Xiong X., Xu F., Wang J., Hou F., et al. (2020). Abnormal topology of brain functional networks in unipolar depression and bipolar disorder using optimal graph thresholding. Prog. Neuropsychopharmacol. Biol. Psychiatry 96:109758. 10.1016/j.pnpbp.2019.109758 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

The raw data supporting the conclusions of this article will be made available by the authors, without undue reservation.