Abstract

The thermal degradation of linalool-chemotype Cinnamomum osmophloeum leaf essential oil and the stability effect of microencapsulation of leaf essential oil with β-cyclodextrin were studied. After thermal degradation of linalool-chemotype leaf essential oil, degraded compounds including β-myrcene, cis-ocimene and trans-ocimene, were formed through the dehydroxylation of linalool; and ene cyclization also occurs to linalool and its dehydroxylated products to form the compounds such as limonene, terpinolene and α-terpinene. The optimal microencapsulation conditions of leaf essential oil microcapsules were at a leaf essential oil to the β-cyclodextrin ratio of 15:85 and with a solvent ratio (ethanol to water) of 1:5. The maximum yield of leaf essential oil microencapsulated with β-cyclodextrin was 96.5%. According to results from the accelerated dry-heat aging test, β-cyclodextrin was fairly stable at 105 °C, and microencapsulation with β-cyclodextrin can efficiently slow down the emission of linalool-chemotype C. osmophloeum leaf essential oil.

Keywords: Cinnamomum osmophloeum, linalool, β-cyclodextrin, microencapsulation

1. Introduction

Natural products from cinnamon plants (Cinnamomum spp., Lauraceae) exhibit various bioactivities, such as antimicrobial, insecticidal, anti-inflammatory, antidiabetic activities and, etc. [1,2,3,4,5]. Cinnamomum osmophloeum Kanehira is commonly used as folk medicines and food flavors. It is scientifically reported that extracts and essential oils of C. osmophloeum exhibit the antioxidant, antibacterial, anxiolytic, xanthine oxidase inhibitory effects, and so forth [6,7,8,9].

Parts of natural plant products, especially essential oils, are highly volatile in the ambient environment and, therefore, may result in thermal oxidation/degradation. Microencapsulation or nanoencapsulation of the essential oils and extracts could provide protection and enhance the stabilization [10,11,12]. Encapsulation materials used include gelatin, cyclodextrins, gum arabic, caseinates, alginates, cellulose derivatives, chitosans, etc. [13,14,15,16]. Properties of natural plant products after microencapsulation would be influenced by the kinds of core-shell structures and coating materials [17,18,19,20].

Cyclodextrins are amphiphilic hollow cyclic oligosaccharides and form the inclusion complexes with versatile molecules [17,21,22]. β-Cyclodextrin, composed of seven α-d-glucopyranose units, is the most common cyclodextrin product and of good durability; it is a multifunctional encapsulation material to keep the bioactive ingredients from volatilization, oxidization, and etc. [23,24,25]. Many researchers have reported the microencapsulation of the bioactive constituents, essentials oil, or supercritical fluid extracts with β-cyclodextrin [9,10,26,27]. Ramos et al. proved that the inclusion of isopulegol, an alcoholic monoterpene, in β-cyclodextrin is an effective method to improve its antiedematogenic and anti-inflammatory activities [28]. Cyclodextrins are appropriate carriers for delivering or releasing natural products in the pharmaceutical, food and cosmetic industries [16,29,30,31,32,33].

The aims of this study were to investigate the thermal degradation of linalool-chemotype C. osmophloeum leaf essential oil, find the optimal reaction conditions of microencapsulation of leaf essential oil with β-cyclodextrin, and evaluate the stabilization of leaf essential oil microcapsules. Through our research, it is expected to reveal the changes in the chemical structure of linalool during thermal decomposition and properly preserve the linalool-chemotype C. osmophloeum leaf essential oil by microencapsulating with β-cyclodextrin.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Hydrodistillation

Fresh C. osmophloeum leaves were collected from Lienhuachih Research Center of Taiwan Forestry Research Institute in Nantou County, Taiwan. Leaves were hydrodistilled in a Clevenger apparatus for 6 h to obtain the leaf essential oil. The yield of leaf essential oil was 3.46 ± 0.06% (w/w). Leaf essential oil was stored in the dark glass bottle and kept in the refrigerator at 4 °C.

2.2. GC–MS Analysis

The constituents of the leaf essential oil were analyzed by Thermo Trace GC Ultra gas chromatograph equipped with a Polaris Q MSD mass spectrometer (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Austin, TX, USA). Each 1 μL analyte was injected into the DB-5MS capillary column (Crossbond 5% phenyl methyl polysiloxane, 30 m length × 0.25 mm i.d. × 0.25 µm film thickness). The temperature program was: 60 °C initial temperature for 1 min; 4 °C/min up to 220 °C and hold for 2 min; and 20 °C/min up to 250 °C and hold for 3 min. The flow rate of carrier gas helium was 1 mL/min, and the split ratio was 1:10. Constituents were identified by comparing the mass spectra (m/z 50–600 amu) with NIST and Wiley library data, Kovats index (KI) [34] and authentic standards. Quantification of constituents was analyzed by integrating the peak area of the chromatogram using GC equipped with the flame ionization detector (FID).

2.3. Microencapsulation

Leaf essential oil microencapsulated with β-cyclodextrin was using the co-precipitation method with slight revisions [35,36,37]. β-Cyclodextrin (5 g) was first dissolved in 300 mL different ratio of ethanol/water solution at 50 °C for 5 min; the solution was cooled down to 25 °C. Linalool/leaf essential oil (0.88 g) was dissolved in 10 mL ethanol; and then added to the β-cyclodextrin solution, stirred at 600 rpm for 1 h. The solution was kept in the refrigerator at 4 °C overnight; the co-precipitated microcapsules were filtered and then washed with 50 mL distilled water. Microcapsules were dried at 50 °C in the oven for 24 h. The yield of leaf oil microcapsules was calculated by the following Formula (1).

| Yield (%) = microcapsules (g)/[β-cyclodextrin (g) + leaf essential oil (g)] × 100 | (1) |

2.4. Accelerated Dry-Heat Aging Test

An accelerated dry-heat aging test (ISO 5630–1; CNS 12,887–1) was used to evaluate the thermostability of leaf oil microcapsules. Microcapsules were heated at 105 °C in a ventilated oven. Weights of leaf oil microcapsules were measured during the accelerated dry-heat aging test (1, 2, 4, and 8 days). After the aging test, weight losses of leaf oil microcapsules were calculated.

2.5. Statistical Analysis

Results data were statistically analyzed using Scheffé’s test of the SAS system (version 9.2, Cary, NC, USA) with a 95% confidence interval. Scheffé’s test is a post hoc multiple comparison method with stringent error control.

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Changes in Composition of C. osmophloeum Leaf Oil after Thermal Degradation

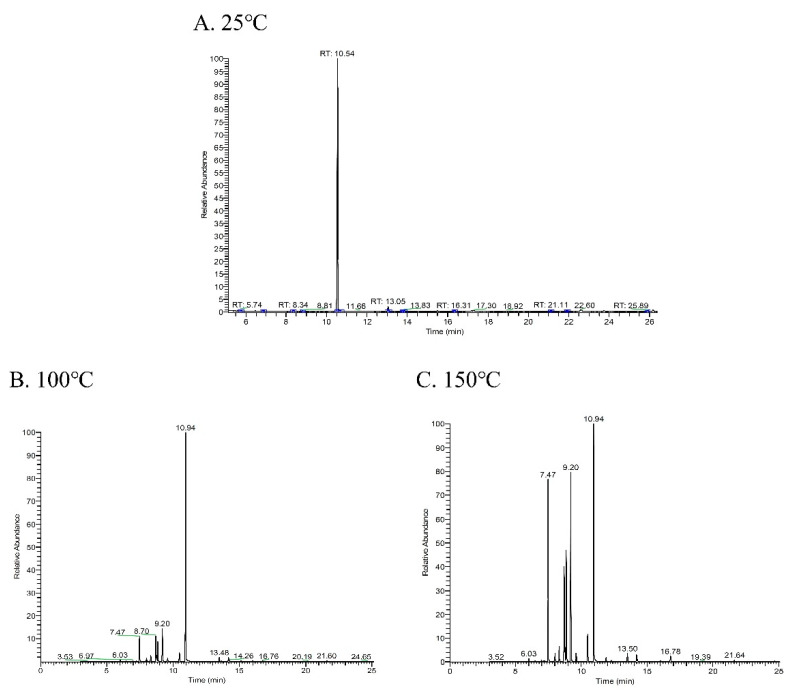

Constituents of C. osmophloeum leaf essential oil were analyzed by GC–MS; a gas chromatogram of leaf essential oil is shown in Figure 1A. The main constituent of leaf essential oil was linalool (93.30%), the other minor constituents were 2-methyl benzofuran (1.99%), α-pinene (0.66%), cinnamyl acetate (0.63%), limonene (0.61%), β-caryophyllene (0.59%), methyl chavicol (0.57%), and trans-cinnamaldehyde (0.52%), as listed in Table 1. Due to the high content of linalool, C. osmophloeum leaf essential oil was classified into the linalool-chemotype.

Figure 1.

Gas chromatogram of linalool-chemotype C. osmophloeum leaf oil after thermal degradation. (A) 25 °C; (B) 100 °C; (C) 150 °C.

Table 1.

Compositions of linalool-chemotype Cinnamomum osmophloeum leaf essential oil after thermal degradation.

| Rt | KI | rKI | Constituent | Content (%) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| (min) | Original | 100 °C | 150 °C | |||

| 6.03 | 938 | 939 | α-Pinene | 0.66 | 0.36 | 0.29 |

| 7.21 | 982 | 979 | β-Pinene | 0.28 | 0.07 | 0.06 |

| 7.47 | 991 | 990 | β-Myrcene | - | 5.56 | 17.89 |

| 8.01 | 1007 | 1002 | α-Phellandrene | - | 0.91 | 0.98 |

| 8.32 | 1017 | 1017 | α-Terpinene | - | 1.49 | 1.69 |

| 8.70 | 1027 | 1029 | Limonene | 0.61 | 7.77 | 11.40 |

| 8.86 | 1032 | 1037 | cis-Ocimene | - | 4.70 | 11.72 |

| 9.20 | 1049 | 1050 | trans-Ocimene | 0.32 | 7.94 | 20.08 |

| 9.60 | 1055 | 1059 | γ-Terpinene | - | 0.86 | 0.97 |

| 10.48 | 1082 | 1088 | Terpinolene | - | 2.53 | 3.37 |

| 10.94 | 1100 | 1096 | Linalool | 93.30 | 64.01 | 27.54 |

| 13.48 | 1180 | - | 2-Methylbenzofuran | 1.99 | 1.23 | 1.07 |

| 14.17 | 1186 | 1188 | α-Terpineol | 0.28 | 1.50 | 1.12 |

| 14.28 | 1198 | 1196 | Methyl chavicol | 0.57 | - | - |

| 16.80 | 1273 | 1270 | trans-Cinnamaldehyde | 0.52 | 0.15 | 0.74 |

| 21.64 | 1420 | 1424 | β-Caryophyllene | 0.59 | 0.22 | 0.17 |

| 22.42 | 1445 | 1446 | Cinnamyl acetate | 0.63 | 0.02 | - |

RT: retention time (min); KI: Kovats index relative to n-alkanes (C9 – C24) on a DB-5MS column; rKI: Kovats index on a DB-5MS column in the reference [34].

As presented in Figure 1B, several significant peaks occurred in the gas chromatogram of leaf essential oil after the heat treatment at 100 °C for 30 min. The content of the main constitute, linalool, was reduced from 93.30% to 64.01% (Table 1). New constituents were observed for β-myrcene (5.56%), α-phellandrene (0.91%), α-terpinene (1.49%), cis-ocimene (4.70%), γ-terpinene, and terpinolene (2.53%) in the thermally degraded leaf essential oil. Major variations were found for the increasing contents of limonene and trans-ocimene, which were 0.61% and 0.32% in the raw leaf essential oil and obviously increased to 7.77% and 7.94% in the thermally degraded specimen.

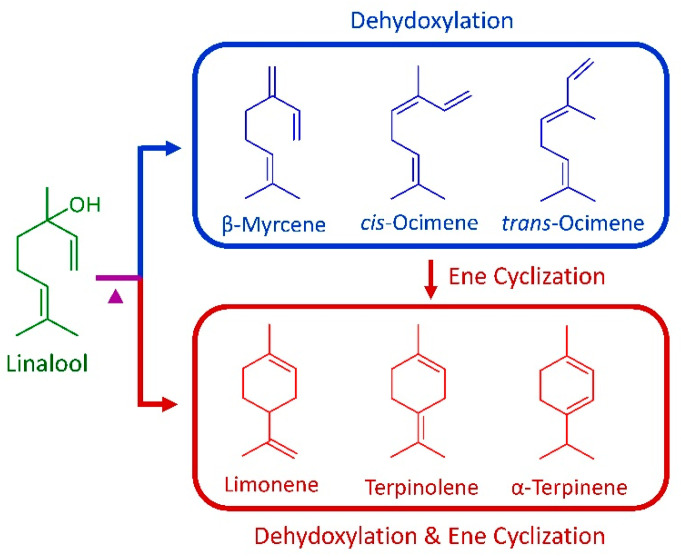

Similar degradation was observed from the gas chromatogram of leaf essential oil after the heat treatment at 150 °C for 30 min (Figure 1C). Linalool had a remarkable decrease in content from 93.30% in the original leaf essential oil to 27.54% in the 150 °C-degraded specimens. The peaks of the new compounds generated under more severe heat treatment became more obvious; trans-ocimene was present in the degraded leaf essential oil of 20.08%, β-myrcene 17.89%, cis-ocimene 11.72%, limonene 11.40%, terpinolene 3.37%, and α-terpinene 1.69%, in comparison with the original leaf essential oil, where these contents were much smaller. The increased amount (65.22%) of these compounds was close to the decrease in linalool (65.76%). Figure 2 illustrates the degradation mechanism of linalool and chemical structures of degradation products. After heat treatments at 100 °C and 150 °C, compounds β-myrcene, cis-ocimene and trans-ocimene were formed through the dehydroxylation of linalool. Moreover, ene cyclization occurred to linalool and its dehydroxylated products, further formed the compounds limonene, terpinolene and α-terpinene.

Figure 2.

Schematic illustration of the thermal degradation of linalool.

Leiner et al. (2013) investigated the pyrolysis behavior of linalool. Linalool was pyrolyzed in a temperature range of 350–600 °C under nitrogen and underwent ene-type cyclization reactions leading to plinols, four cyclopentanol compounds [38]. The result varied from this study may be due to the different heating temperatures and the environment (under N2 or under air).

3.2. Optimization of Microencapsulation of Leaf Essential Oil with β-Cyclodextrin

The preparation method of microencapsulation can influence the property of β-cyclodextrin microcapsules. Kfoury et al. (2016) studied the aroma release effect from the solid inclusion complexes of β-cyclodextrin with trans-anethole by two preparation methods, freeze-drying (FD) and co-precipitation coupled to FD (Cop-FD). Cop-FD microcapsules retained more efficiently trans-anethole than that of FD microcapsules; it revealed co-precipitation method provide superior inclusion characteristics [12].

The specimen to β-cyclodextrin ratio and the solvent ratio is the important factors that influence the yield of microcapsules. Yields of linalool and leaf essential oil microencapsulated with β-cyclodextrin by different reaction conditions are presented in Table 2. β-Cyclodextrin completely dissolved in the solution (ethanol/water, 1:2 v/v) by heating at 50 °C for 5 min, then the solution was cooled down to 25 °C without adding the core material, and no powders/crystals formed or precipitated even at 4 °C. The highest yield of microcapsule was 94.2% at the linalool to the β-cyclodextrin ratio of 15:85 (w/w), which was quite close to the molar ratio (linalool:β-cyclodextrin) of 1:1.

Table 2.

Yields of linalool and leaf essential oil microencapsulated with β-cyclodextrin.

| Specimen | Specimen: β-CD (w/w) |

EtOH: H2O (v/v) |

Yield (%) |

|---|---|---|---|

| 0:100 | 1:2 | 0.0 ± 0.0 d* | |

| 5:95 | 1:2 | 54.3 ± 3.1 a* | |

| Linalool | 10:90 | 1:2 | 86.9 ± 0.2 b |

| 15:85 | 1:2 | 94.2 ± 0.4 c | |

| 20:80 | 1:2 | 91.0 ± 0.5 b,c | |

| 15:85 | 1:7 | 93.3 ± 0.6 B | |

| 15:85 | 1:5 | 98.1 ± 0.1 C | |

| Linalool | 15:85 | 1:3 | 97.0 ± 0.4 C |

| 15:85 | 1:2 | 94.2 ± 0.4 B | |

| 15:85 | 1:1 | 83.4 ± 1.8 A | |

| Leaf essential oil | 15:85 | 1:5 | 96.5 ± 0.2 |

*: Different letters (a–d and A–C) in Table refer to statistically significant difference at the level of p < 0.05 according to Scheffé’s test.

As for the ethanol/water ratio, the highest yield of microcapsule was 98.1% under the 1:5 ratio of ethanol to water. There was no statistically significant difference in the microcapsule yields between the solvent ratio of 1:3 and 1:5 (p < 0.05). Using the optimal reaction conditions, the yield of linalool-chemotype leaf essential oil microencapsulated with β-cyclodextrin was 96.5%.

3.3. Stabilization and Release of Leaf Essential Oil Microcapsules

The constituents of common essential oils from aroma plants are small molecular weight and highly volatile. The encapsulation of limonene would influence its properties, such as evaporation, stabilization and controlled release, by different encapsulation methods and selected materials. The retention of limonene in extruded starch (non-encapsulation) was quite low (8.0%) compared with that of limonene microencapsulated with β-cyclodextrin (92.2%) [20].

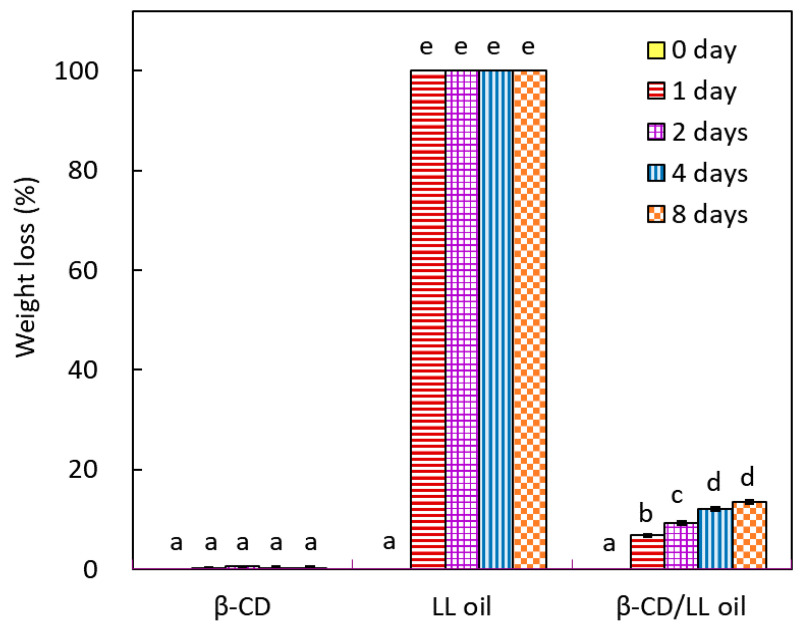

Using the accelerated dry-heat aging test to evaluate the stability and release of leaf essential oil microcapsules. Figure 3 shows the weight losses of β-cyclodextrin (β-CD), linalool-chemotype leaf essential oil (LL oil), and leaf oil microcapsules (β-CD/LL oil) at 105 °C during the accelerated aging period. The weight loss of β-CD was very slight (less than 0.5%) after 8 days of the accelerated aging test; it indicated that β-CD was thermostable at 105 °C. Trotta et al. (2000) investigated the thermal behavior of β-CD; the decomposition temperature of β-cyclodextrin was 250 °C by using the thermogravimetric analysis (TGA) [39]. Weight losses of linalool-chemotype leaf essential oil was 99.1% after 30 min at 105 °C (data not shown in Figure 2); leaf essential oil exhibited highly volatile in the high-temperature environment. Weight losses of leaf essential oil microcapsules were 6.73%, 9.33%, 12.14%, and 13.40% after 1, 2, 4, and 8 days of the aging test, respectively. Results revealed that microencapsulation with β-cyclodextrin slowed down the release/emission of leaf essential oil in the dry-heat aging test and improved the thermal stabilization of linalool-chemotype leaf essential oil.

Figure 3.

Changes in weight loss of leaf essential oil microcapsules during the dry-heat aging period. β-CD: β-cyclodextrin; LL oil: C. osmophloeum leaf oil; β-CD/LL oil: leaf oil microcapsules; different letters (a–e) in the figure refer to the statistically significant difference at the level of p < 0.05 according to the Scheffé’s test.

4. Conclusions

The thermal degradation of linalool-chemotype C. osmophloeum leaf oil is investigated by GC–MS. After the heat treatment, compounds β-myrcene, cis-ocimene and trans-ocimene form through the dehydroxylation of linalool and compounds limonene, terpinolene and α-terpinene by a further ene cyclization. The significantly high microcapsule yield of 96.5% is obtained from the optimal reaction conditions with the leaf essential oil to the β-cyclodextrin ratio of 15:85 and ethanol to water ratio of 1:5. Based on the accelerated dry-heat aging assay, β-cyclodextrin is stable under the environment at 105 °C, and microencapsulation with β-cyclodextrin effectively slows down the release/emission of leaf essential oil.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank the Taiwan Forestry Bureau for the financial support and the Taiwan Forestry Research Institute for the collection of plant material.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, S.-T.C. and H.-T.C.; methodology, C.-Y.L., L.-S.H. and H.-T.C.; formal analysis and Investigation, C.-Y.L., L.-S.H. and H.-T.C.; writing and Editing, S.-T.C. and H.-T.C. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by Forestry Bureau, Council of Agriculture, Executive Yuan, Taipei, Taiwan.

Data Availability Statement

The data are available are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Sample Availability

Samples are available the corresponding author.

Footnotes

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Bandara T., Uluwaduge I., Jansz E.R. Bioactivity of cinnamon with special emphasis on diabetes mellitus: A review. Int. J. Food Sci. Nutr. 2012;63:380–386. doi: 10.3109/09637486.2011.627849. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Melgarejo-Flores B.G., Ortega-Ramirez L.A., Silva-Espinoza B.A., Gonzalez-Aguilar G.A., Miranda M.R.A., Ayala-Zavala J.F. Antifungal protection and antioxidant enhancement of table grapes treated with emulsions, vapors, and coatings of cinnamon leaf oil. Postharvest Biol. Technol. 2013;86:321–328. doi: 10.1016/j.postharvbio.2013.07.027. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Rao P.V., Gan S.H. Cinnamon: A multifaceted medicinal plant. Evid. Based Complement. Altern. Med. 2014;2014:642942. doi: 10.1155/2014/642942. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Davaatseren M., Jo Y.J., Hong G.P., Hur H.J., Park S., Choi M.J. Studies on the Anti-oxidative function of trans-cinnamaldehyde-included β-cyclodextrin complex. Molecules. 2017;21:1644. doi: 10.3390/molecules22121868. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kumar S., Kumari R., Mishra S. Pharmacological properties and their medicinal uses of Cinnamomum: A review. J. Pharm. Pharmacol. 2019;71:1735–1761. doi: 10.1111/jphp.13173. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Wu C.L., Chang H.T., Hsui Y.R., Hsu Y.W., Liu J.Y., Wang S.Y., Chang S.T. Antioxidant-enriched leaf water extracts of Cinnamomum osmophloeum from eleven provenances and their bioactive flavonoid glycosides. BioResources. 2013;5:571–580. doi: 10.15376/biores.8.1.571-580. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Chang S.T., Chen P.F., Chang S.C. Antibacterial activity of leaf essential oils and their constituents from Cinnamomum osmophloeum. J. Ethnopharmacol. 2001;77:123–127. doi: 10.1016/S0378-8741(01)00273-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Cheng B.H., Sheen L.Y., Chang S.T. Evaluation of anxiolytic potency of essential oil and S-(+)-linalool from Cinnamomum osmophloeum ct. linalool leaves in mice. J. Tradit. Complement. Med. 2015;5:27–34. doi: 10.1016/j.jtcme.2014.10.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Huang C.Y., Yeh T.F., Hsu F.L., Lin C.Y., Chang S.T., Chang H.T. Xanthine oxidase inhibitory activity and thermostability of cinnamaldehyde-chemotype leaf oil of Cinnamomum osmophloeum microencapsulated with β-cyclodextrin. Molecules. 2018;23:1107. doi: 10.3390/molecules23051107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kaiser C.S., Rompp H., Schmidt P.C. Supercritical carbon dioxide extraction of chamomile flowers: Extraction efficiency, stability, and in-line inclusion of chamomile-carbon dioxide extract in β-cyclodextrin. Phytochem. Anal. 2004;15:249–256. doi: 10.1002/pca.775. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Wang J., Cao Y., Sun B., Wang C. Physicochemical and release characterisation of garlic oil-β-cyclodextrin inclusion complexes. Food Chem. 2011;127:1680–1685. doi: 10.1016/j.foodchem.2011.02.036. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kfoury M., Auezova L., Greige-Gerges H., Larsen K.L., Fourmentin S. Release studies of trans-anethole from β-cyclodextrin solid inclusion complexes by multiple headspace extraction. Carbohydr. Polym. 2016;151:1245–1250. doi: 10.1016/j.carbpol.2016.06.079. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Pires M.A.S., Santos R.A.S., Sinisterra R.D. Pharmaceutical composition of hydrochlorothiazide: β-cyclodextrin: Preparation by three different methods, physico-chemical characterization and in vivo diuretic activity evaluation. Molecules. 2011;16:4482–4499. doi: 10.3390/molecules16064482. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Moya-Ortega M.D., Alvarez-Lorenzo C., Concheiro A., Loftsson T. Cyclodextrin- based nanogels for pharmaceutical and biomedical applications. Int. J. Pharm. 2012;428:152–163. doi: 10.1016/j.ijpharm.2012.02.038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Szente L., Szeman J., Sohajda T. Analytical characterization of cyclodextrins: History, official methods and recommended new techniques. J. Pharm. Biomed. Anal. 2016;130:347–365. doi: 10.1016/j.jpba.2016.05.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Braga S.S. Cyclodextrins: Emerging medicines of the new millennium. Biomolecules. 2019;9:801. doi: 10.3390/biom9120801. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Guimaraes A.G., Oliveira M.A., Alves R.S., Menezes P.P., Serafini M.R., Araujo A.A.S., Bezerra D.P., Quintans L.J. Encapsulation of carvacrol, a monoterpene present in the essential oil of oregano, with β-cyclodextrin, improves the pharmacological response on cancer pain experimental protocols. Chem. Biol. Interact. 2015;227:69–76. doi: 10.1016/j.cbi.2014.12.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Nascimento S.S., Araujo A.A.S., Brito R.G., Serafini M.R., Menezes P.P., DeSantana J.M., Lucca W., Alves P.B., Blank A.F., Oliveira R.C.M., et al. Cyclodextrin-complexed Ocimum basilicum leaves essential oil increases fos protein expression in the central nervous system and produce an antihyperalgesic effect in animal models for fibromyalgia. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2015;16:547–563. doi: 10.3390/ijms16010547. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Bomfim L.M., Menezes L.R., Rodrigues A.C., Dias R.B., Rocha C.A., Soares M.B., Neto A.F., Nascimento M.P., Campos A.F., Silva L.C., et al. Antitumour activity of the microencapsulation of Annona vepretorum essential oil. Basic Clin. Pharmacol. Toxicol. 2016;118:208–213. doi: 10.1111/bcpt.12488. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ibanez M.D., Sanchez-Ballester N.M., Blazquez M.A. Encapsulated limonene: A pleasant lemon-like aroma with promising application in the agri-food industry. A review. Molecules. 2020;25:2598. doi: 10.3390/molecules25112598. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Szejtli J. Introduction and general overview of cyclodextrin chemistry. Chem. Rev. 1998;98:1743–1753. doi: 10.1021/cr970022c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Spada G., Gavini E., Cossu M., Rassu G., Carta A., Giunchedi P. Evaluation of the effect of hydroxypropyl β-cyclodextrin on topical administration of milk thistle extract. Carbohydr. Polym. 2013;92:40–47. doi: 10.1016/j.carbpol.2012.09.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Hill L.E., Gomes C., Taylor T.M. Characterization of beta-cyclodextrin inclusion complexes containing essential oils (trans-cinnamaldehyde, eugenol, cinnamon bark, and clove bud extracts) for antimicrobial delivery applications. LWT-Food Sci. Technol. 2013;51:86–93. doi: 10.1016/j.lwt.2012.11.011. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Maes C., Bouquillon S., Fauconnier M.L. Encapsulation of essential oils for the development of biosourced pesticides with controlled release: A review. Molecules. 2019;24:2539. doi: 10.3390/molecules24142539. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Becerril R., Nerin C., Silva F. Encapsulation systems for antimicrobial food packaging components: An update. Molecules. 2020;25:1134. doi: 10.3390/molecules25051134. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Quintans J.S.S., Menezes P.P., Santos M.R.V., Bonjardim L.R., Almeida J.R.G.S., Gelain D.P., Araujo A.A.S., Quintans-Junior L.J. Improvement of p-cymene antinociceptive and anti-inflammatory effects by inclusion in β-cyclodextrin. Phytomedicine. 2013;20:436–440. doi: 10.1016/j.phymed.2012.12.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Jiang S., Li J.N., Jiang Z.T. Inclusion reactions of β-cyclodextrin and its derivatives with cinnamaldehyde in Cinnamomum loureirii essential oil. Eur. Food. Res. Technol. 2010;230:543–550. doi: 10.1007/s00217-009-1192-z. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Ramos A.G.B., de Menezes I.R.A., da Silva M.S.A., Pessoa R.T., de Lacerda Neto L.J., Passos F.R.S., Coutinho H.D.M., Iriti M., Quintans-Junior L.J. Antiedematogenic and anti-inflammatory activity of the monoterpene isopulegol and its β-cyclodextrin (β-CD) inclusion complex in animal inflammation models. Foods. 2020;9:630. doi: 10.3390/foods9050630. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Waleczek K.J., Marques H.M.C., Hempel B., Schmidt P.C. Phase solubility studies of pure (2)-α-bisabolol and camomile essential oil with β-cyclodextrin. Eur. J. Pharm. Biopharm. 2003;55:247–251. doi: 10.1016/S0939-6411(02)00166-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Iacovino R., Caso J.V., Rapuano F., Russo A., Isidori M., Lavorgna M., Gaetano Malgieri G., Isernia C. Physicochemical characterization and cytotoxic activity evaluation of hydroxymethylferrocene: β-cyclodextrin inclusion complex. Molecules. 2012;17:6056–6070. doi: 10.3390/molecules17056056. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Iacovino R., Rapuano F., Caso J.V., Russo A., Lavorgna M., Russo C., Isidori M., Russo L., Malgieri G., Isernia C. β-Cyclodextrin inclusion complex to improve physicochemical properties of pipemidic acid: Characterization and bioactivity evaluation. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2013;14:13022–13041. doi: 10.3390/ijms140713022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Ciobanu A., Mallard I., Landy D., Brabie G., Nistor D., Fourmentin S. Retention of aroma compounds from Mentha piperita essential oil by cyclodextrins and crosslinked cyclodextrin polymers. Food Chem. 2013;138:291–297. doi: 10.1016/j.foodchem.2012.10.106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Donato C.D., Lavorgna M., Fattorusso R., Isernia C., Isidori M., Malgieri G., Piscitelli C., Russo C., Russo L., Iacovino R. Alpha- and beta-cyclodextrin inclusion complexes with 5-fluorouracil: Characterization and cytotoxic activity evaluation. Molecules. 2016;22:1868. doi: 10.3390/molecules21121644. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Adams R.P. Identification of Essential Oil Components by Gas Chromatography/Mass Spectrometry. Allured Publishing Corporation; Carol Stream, IL, USA: 2007. pp. 6–398. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Ayala-Zavala J.F., Soto-Valdez H., Gonzalez-Leon A., Alvarez-Parrilla E., Martin-Belloso O., Gonzalez-Aguilar G.A. Microencapsulation of cinnamon leaf (Cinnamomum zeylanicum) and garlic (Allium sativum) oils in β-cyclodextrin. J. Incl. Phenom. Macrocycl. Chem. 2008;60:359–368. doi: 10.1007/s10847-007-9385-1. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Liu H., Yang G., Tang Y., Cao D., Qi T., Qi Y., Fan G. Physicochemical characterization and pharmacokinetics evaluation of β-caryophyllene/β-cyclodextrin inclusion complex. Int. J. Pharm. 2013;450:304–310. doi: 10.1016/j.ijpharm.2013.04.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Abarca R.L., Rodriguez F.J., Guarda A., Galotto M.J., Bruna J.E. Characterization of beta-cyclodextrin inclusion complexes containing an essential oil component. Food Chem. 2016;196:968–975. doi: 10.1016/j.foodchem.2015.10.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Leiner J., Stolle A., Ondruschka B., Netscher T., Bonrath W. Thermal behavior of pinan-2-ol and linalool. Molecules. 2013;18:8358–8375. doi: 10.3390/molecules18078358. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Trotta F., Zanetti M., Camino G. Thermal degradation of cyclodextrins. Polym. Degrad. Stab. 2000;69:373–379. doi: 10.1016/S0141-3910(00)00084-7. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

The data are available are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.