Abstract

The most common localization for intestinal Crohn’s disease (CD) is the terminal ileum and ileocecal area. It is estimated that patients with CD have one in four chance of undergoing surgery during their life. As surgery in ulcerative colitis ultimately cures the disease, in CD, regardless of the extent of bowel removed, the risk of disease recurrence is as high as 40%. In elective surgery, management of isolated Crohn’s colitis continues to evolve. Depending on the type of surgery performed, colonic CD patients often require further medical or surgical therapy to prevent or treat recurrence. The elective surgical treatment of colonic CD is strictly dependent on the localization of disease, and the choice of the procedure is dependent of the extent of colonic involvement and previous resection. The most common surgical options in colonic CD are total proctocolectomy (TPC) with permanent ileostomy, segmental bowel resection, subtotal colectomy. TPC completely removes all colonic and rectal disease and avoids the use of a potentially diseased anus. We will review current options for the elective surgical treatment of colonic CD, based on the current literature and our own personal experience.

Keywords: Crohn’s disease, Colonic Crohn’s disease, Surgery, Surgical treatment, Colonic resection, Segmental colectomy, Total colectomy

Core Tip: The most common localization for intestinal Crohn’s disease (CD) is the terminal ileum and ileocecal area. In elective surgery, management of isolated Crohn’s colitis continues to evolve. As surgery in ulcerative colitis ultimately cures the disease, in CD, regardless of the extent of bowel removed, the risk of disease recurrence is as high as 40%. Depending on the type of surgery performed, colonic CD patients often require further medical or surgical therapy to prevent or treat recurrence. The elective surgical treatment of colonic CD is strictly dependent on the localization of disease, and the choice of the procedure is dependent of the extent of colonic involvement and previous resection.

INTRODUCTION

The most common localization for intestinal Crohn’s disease (CD) is the terminal ileum and ileocecal area. CD can involve the entirety of the gastrointestinal tract and can be multifocal[1]. Incidence of isolated colonic CD varies from 25% to 60% of all comers[2]. In up to 40% of colonic CD, the rectum is spared from inflammation, a prerequisite for restoration of intestinal continuity in favorable cases, in contrast with ulcerative colitis (UC), where rectal involvement is the norm[2,3]. On the other hand, severe perianal fistulizing CD is a contraindication to restorative procedures.

COLONIC CROHN'S DISEASE

Colonic CD has clinical and phenotypical features that are different from the more common ileitis (Table 1). Colonic CD without perianal fistulizing involvement is often associated with a less aggressive phenotype and lower indication to surgery than ileal or ileocolonic CD[1,4]. Extraintestinal symptoms are statistically more frequent in colonic CD[5].

Table 1.

Features of ileal/ileocolonic Crohn’s disease, isolated colonic Crohn’s disease, and ulcerative colitis

| Characteristics | Ileal and ileocolonic CD | Isolated colonic CD | Ulcerative colitis |

| Sex | Slight female predominance (55%) | Female predominance (65%) | Equal or slight male predominance |

| Genetics | Crohn’s-associated genotype including NOD2/CARD15 | Genotype midway between CD and UC | UC-associated genotype including HLA-DRB1*01:03 |

| Serology | ASCA commonly positive; pANCA usually negative | ASCA less commonly positive than ileal CD; pANCA positive | ASCA usually negative; pANCA commonly positive |

| Mucosa-associated microbiota | Marked changes commonly including increased proteobacteria (e.g., E. coli) and fusobacteria | Intermediate changes similar to ileal/ileocolonic CD but less consistent | Modest changes, including slight increase in E. coli |

| Response to mesalazine | No efficacy | No efficacy | Good efficacy |

| Response to anti-TNF | Good efficacy | Good efficacy, probably better than for ileal/ileocolonic CD | Good efficacy |

| Response to exclusive enteral nutrition | Good efficacy | Probably good efficacy | No efficacy |

| Surgery rate and type | Required in majority | Required in minority. High failure for pouch-anal reconstruction | Required in minority. Low failure for pouch-anal reconstruction |

CD: Crohn’s disease; ASCA: Anti-Saccharomyces cerevisiae; HLA: Human leucocyte antigen; pANCA: Perinuclear antineutrophil cytoplasmic antibodies; TNF: Tumor necrosis factor; UC: Ulcerative colitis.

It is estimated that patients with CD have one in four chance of undergoing surgery during their life, but as surgery in UC ultimately cures the disease, in CD, regardless of the extent of bowel removed, the risk of disease recurrence is as high as 40%[6]. Depending on the type of surgery performed, colonic CD patients often require further medical or surgical therapy to prevent or treat recurrence.

Up to 31% of all colonic CD patients will require an end ileostomy in their lifetime. Restoration of intestinal continuity and preservation of adequate function and quality of life are of paramount importance.

The indication for operative management of CD include acute disease complications (i.e., toxic colitis with or without associated megacolon, hemorrhage, and perforation), chronic disease complications, such as neoplasia, growth retardation, and extra-intestinal manifestations, or failed medical therapy[2]. Failed medical therapy can take several forms including unresponsive disease, incomplete response, mediation-related complications, and non-compliance with pharmacological therapies.

The surgical treatment of colonic CD is strictly dependent on the localization of disease, disease phenotype and patient’s physiologic characteristics. Timing of surgery is critical to avoid an urgent operation often associated with postoperative complications and a temporary or permanent fecal diversion. The most common post-operative complications, such as leakage, abscess and peritonitis, occur in 13%-17% of all procedures, mostly when carried in emergency setting[7].

Patients suffering intraabdominal septic complications have statistically significantly higher 1-, 2-, 5-, and 10-year surgical recurrence rates (25%, 29%, 50%, and 57%) than patients without such complications (4%, 7%, 19%, and 38%, P = 0.0003)[8].

Patients undergoing emergency surgery for CD are at high risk for surgical site infections (SSI), due to severe malnutrition, anemia, immunosuppression secondary to medical therapy (especially with steroids) and chronic illness[7,9]. Previous studies have looked at the efficacy of oral antimicrobial prophylaxis with mechanical preparation during inflammatory bowel disease surgery, with a reduction in SSI of 10% when CD patients are treated with oral and intravenous antimicrobial prophylaxis[9]. However, surgery for Crohn is often complicated by the presence active intraabdominal infection and strictures precluding effective bowel preparation. This results in a higher risk of SSI in CD patients when compared to other elective colorectal operations[10].

In severe fulminant isolated CD or indeterminate colitis the surgical approach of choice is a subtotal colectomy (SC) with end ileostomy. The procedure can often be performed laparoscopically and it is usually well tolerated if properly timed. Moreover, it leaves a chance to restore the sphincter function.

In elective surgery, management of isolated Crohn’s colitis continues to evolve[11-13]. In this article, we will review current options for the elective surgical treatment of colonic CD, based on the current literature and our own personal experience.

Accurate preoperative assessment of the disease and patient’s characteristics are mandatory, especially in terms of location and natural history of the disease, previous resections, current therapy and general medical conditions. Since preoperative anemia, such as hemoglobin level of < 10 g/dL, is associated with an increased postoperative anastomotic leakage rate, an adequate treatment of anemia is mandatory before surgery. Nutrition and drug therapy optimization are advised in the elective setting[7]. In presence of abscess or signs of sepsis, surgery should be postponed after percutaneous or laparoscopic drainage and antibiotic treatment. Parenteral nutrition is also advised and liberally used in these patients.

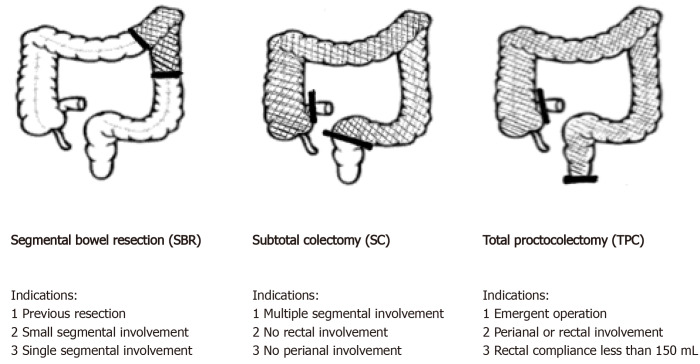

The elective surgical treatment of colonic CD is strictly dependent on the localization of disease, and the choice of the procedure is dependent of the extent of colonic involvement and previous resection (Figure 1). The most common surgical options in colonic CD are total proctocolectomy (TPC) with permanent ileostomy, segmental bowel resection (SBR), SC. TPC completely removes all colonic and rectal disease and avoids the use of a potentially diseased anus.

Figure 1.

Surgical procedures and indications in isolated colonic Crohn’s disease.

Perianal manifestations are linked to increased progression to complicated colonic CD.

The fecal stream plays an important role on the genesis of CD. Fistulizing disease in CD has a poor outcome if not properly treated. The fistulas can be treated through traditional surgery as seton drainage and long-term antibiotics, but exclusion of anal function, even temporary, can help in refractory perianal CD. Most recently the use of monoclonal antibodies to tumor necrosis factor alfa has been described to enhance healing of fistula, including perianal, in CD and allow to make a safe anastomosis in 80% of patient primarily treated with resection and terminal ileostomy, while allowing the healing of perianal disease when administered preoperatively in a number of patients.

In spite of new therapies, severe rectal and perianal involvement remains a contraindication to primary anastomosis, due to a high incidence (50%) of complications, such as leakage and refractory complex rectal fistula. Consequently, in the presence of perianal or rectal disease and colitis, TPC should be preferred.

Patients with proctocolitis that warrant operative treatment usually require a TPC with creation of a permanent ileostomy, especially those persons with colitis whose proctitis, anorectal sphincter dysfunction, or anoperineal sepsis is too severe for rectal preservation. In patients with CD recurrence in the small bowel after TPC is the lowest of all surgical options (around 30%).

TPC with permanent stoma is the safest option to avoid further operations in high-risk patients. On the other hand, TPC carries significant risks of perineal wound and stoma complications[6] and many patients prefer to avoid a permanent stoma. This has led to the adoption of sphincter preserving surgical strategies including segmental colectomy for limited disease and SC with anastomosis when the rectum is healthy.

SBR for CD colitis may offer improved function and a lower risk of a permanent stoma in the short term, but in the long-term recurrence rates as high as 50% (from 32% to 62% in different series)[6,13-19] can affect the anastomosis and other sites in the colon (Table 2). This technique showed an increased risk of postoperative complications[6]. Time to recurrence is faster following SBR compared to other surgical procedures; these patients require immunosuppressive medications and develop drug refractory distal disease.

Table 2.

Recurrence after segmental bowel resection and after total colectomy in patients with isolated colonic Crohn’s disease

| Ref. | Patient/type of surgery | Recurrence rate (%) |

| Longo et al[16], 1988 | 18 segmental bowel resection | 62 |

| 131 total colectomy | 65 | |

| Allan et al[15], 1989 | 36 segmental bowel resection | 66 |

| 63 total colectomy | 53 | |

| Bernell et al[18], 2001 | 134 segmental bowel resection | 49 |

| 106 total colectomy | 53 | |

| Andersson et al[19], 2002 | 31 segmental bowel resection | 39 |

| 26 total colectomy | 46 | |

| Martel et al[17], 2002 | 84 segmental bowel resection | 43 |

| 39 total colectomy | 41 | |

| Fichera et al[13], 2005 | 55 segmental bowel resection | 38.8 |

| 49 total colectomy | 22.9 | |

| 75 total proctocolectomy | 9.3 |

However, segmental colectomy allows a good colonic function and a perceived postoperative quality of life that is the highest of the three procedures.

Indication to SBR are a single colonic CD localization (< 20 cm of macroscopic involvement)[20].

Patients with extensive colonic involvement, or multiple segmental involvement, relative rectal sparing, and adequate ano-rectal continence are candidates to SC and ileo-rectal anastomosis. The recurrence rate for this approach varies from 41% to 74% in different series[6,14]. Both SC and SBR are equally effective treatment options for colonic CD with limited colonic involvement. Segmental colectomy is associated with earlier recurrences than subtotal/total procedure.

It should be emphasized that a recurrence can be treated medically and can take place years after the index surgery. Therefore, segmental or SC with ileorectal anastomosis allow a reasonable quality of life in young patients for a number of years, delaying the need for permanent fecal diversion.

Despite the increasing experience with laparoscopy in CD, one-fifth of selected cases still need conversion[12,21,22]. Several conditions, such as recurrent CD with dense adhesions, abdominopelvic sepsis, fistulizing CD, inflammatory mass, are at risk of a laparotomy, and when the severity of these condition is preoperatively known, a primary open approach should be considered. As far as laparoscopic techniques in colonic CD, even in high volume centers for Crohn surgery the conversion rates are higher than 25%[23]. Laparoscopy is the gold standard for ileocecal resection in CD[12], and several studies have demonstrated the superiority of laparoscopy over laparotomy in this setting, but the learning curve of colonic CD is steeper[24].

CONCLUSION

In conclusion the surgeon must remember that CD cannot be cured with surgery only. Instead, surgery is used in conjunction with maximal medical therapy to treat symptoms of the disease and improve the patient's quality of life. Surgical interventions should be limited in scope.

The management of isolated CD colitis continues to evolve. A surgical approach appears mandatory when the disease is no longer responsive to medical therapies, or when the complications of medical therapies become debilitating. Preoperative treatment with antibiotics, nutritional support, percutaneous drains, optimization of the medical treatment should be considered before colonic resection with a planned anastomosis. In CD colitis, a planned surgery avoids an emergency operation and the need for ileostomy. SBR were associated with the increased likelihood of developing postoperative SSI as opposed to extended colectomies. Segmental resections were performed mostly for strictures or fistulae/abscesses in the descending or sigmoid colon, and, in addition, more of these procedures were safely completed by an anastomosis. Extended colectomies were performed for non-stricturing/non-penetrating disease and were more often completed by stoma formation.

Elective surgery is strictly dependent on the localization of the disease. The choice of procedure is dependent of the extent of colonic involvement and previous resection of the small bowel. The presence and extent of proctitis should be taken into account especially when planning left-sided resections.

Isolated colonic CD patients tend to have better outcomes if treated in high-volume centers, and in the absence of local expertise, patients requiring elective surgery should be referred to a specialist unit.

Footnotes

Conflict-of-interest statement: The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Manuscript source: Invited manuscript

Peer-review started: November 12, 2020

First decision: November 29, 2020

Article in press: December 11, 2020

Specialty type: Gastroenterology and hepatology

Country/Territory of origin: Italy

Peer-review report’s scientific quality classification

Grade A (Excellent): 0

Grade B (Very good): B

Grade C (Good): 0

Grade D (Fair): 0

Grade E (Poor): 0

P-Reviewer: Stift A S-Editor: Chen XF L-Editor: A P-Editor: Li JH

Contributor Information

Maria Michela Chiarello, Department of Surgery, General Surgery Operative Unit, San Giovanni di Dio Hospital, Crotone 88900, Italy.

Maria Cariati, Department of Surgery, General Surgery Operative Unit, San Giovanni di Dio Hospital, Crotone 88900, Italy.

Giuseppe Brisinda, Department of Medical and Surgical Sciences, Abdominal Surgery Clinical Area, Catholic School of Medicine, Fondazione Policlinico Universitario A Gemelli IRCCS, Rome 00168, Italy. gbrisin@tin.it.

References

- 1.Justiniano CF, Aquina CT, Becerra AZ, Xu Z, Boodry CI, Swanger AA, Monson JRT, Fleming FJ. Postoperative Mortality After Nonelective Surgery for Inflammatory Bowel Disease Patients in the Era of Biologics. Ann Surg. 2019;269:686–691. doi: 10.1097/SLA.0000000000002628. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Tonelli F, Paroli GM. [Colorectal Crohn's disease: indications to surgical treatment] Ann Ital Chir. 2003;74:665–672. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Scaringi S, Di Martino C, Zambonin D, Fazi M, Canonico G, Leo F, Ficari F, Tonelli F. Colorectal cancer and Crohn's colitis: clinical implications from 313 surgical patients. World J Surg. 2013;37:902–910. doi: 10.1007/s00268-013-1922-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Arora U, Kedia S, Garg P, Bopanna S, Jain S, Yadav DP, Goyal S, Gupta V, Sahni P, Pal S, Dash NR, Madhusudhan KS, Sharma R, Makharia G, Ahuja V. Colonic Crohn's Disease Is Associated with Less Aggressive Disease Course Than Ileal or Ileocolonic Disease. Dig Dis Sci. 2018;63:1592–1599. doi: 10.1007/s10620-018-5041-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Toshniwal J, Chawlani R, Thawrani A, Sharma R, Arora A, Kotecha HL, Goyal M, Kirnake V, Jain P, Tyagi P, Bansal N, Sachdeva M, Ranjan P, Kumar M, Sharma P, Singla V, Bansal R, Shah V, Bhalla S, Kumar A. All ileo-cecal ulcers are not Crohn's: Changing perspectives of symptomatic ileocecal ulcers. World J Gastrointest Endosc. 2017;9:327–333. doi: 10.4253/wjge.v9.i7.327. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Angriman I, Pirozzolo G, Bardini R, Cavallin F, Castoro C, Scarpa M. A systematic review of segmental vs subtotal colectomy and subtotal colectomy vs total proctocolectomy for colonic Crohn's disease. Colorectal Dis. 2017;19:e279–e287. doi: 10.1111/codi.13769. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Chiarello MM, Brisinda G. A commentary on: Preoperative hypoalbuminemia is an independent risk factor for postoperative complications in Crohn's disease patients with normal BMI: A cohort study. Int J Surg. 2020;81:100–101. doi: 10.1016/j.ijsu.2020.07.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Iesalnieks I, Spinelli A, Frasson M, Di Candido F, Scheef B, Horesh N, Iborra M, Schlitt HJ, El-Hussuna A. Risk of postoperative morbidity in patients having bowel resection for colonic Crohn's disease. Tech Coloproctol. 2018;22:947–953. doi: 10.1007/s10151-018-1904-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Uchino M, Ikeuchi H, Bando T, Chohno T, Sasaki H, Horio Y, Nakajima K, Takesue Y. Efficacy of Preoperative Oral Antibiotic Prophylaxis for the Prevention of Surgical Site Infections in Patients With Crohn Disease: A Randomized Controlled Trial. Ann Surg. 2019;269:420–426. doi: 10.1097/SLA.0000000000002567. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Cima RR, Bergquist JR, Hanson KT, Thiels CA, Habermann EB. Outcomes are Local: Patient, Disease, and Procedure-Specific Risk Factors for Colorectal Surgical Site Infections from a Single Institution. J Gastrointest Surg. 2017;21:1142–1152. doi: 10.1007/s11605-017-3430-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kiran RP, Nisar PJ, Church JM, Fazio VW. The role of primary surgical procedure in maintaining intestinal continuity for patients with Crohn's colitis. Ann Surg. 2011;253:1130–1135. doi: 10.1097/SLA.0b013e318212b1a4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Mege D, Michelassi F. Laparoscopy in Crohn Disease: Learning Curve and Current Practice. Ann Surg. 2020;271:317–324. doi: 10.1097/SLA.0000000000002995. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Fichera A, McCormack R, Rubin MA, Hurst RD, Michelassi F. Long-term outcome of surgically treated Crohn's colitis: a prospective study. Dis Colon Rectum. 2005;48:963–969. doi: 10.1007/s10350-004-0906-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Tekkis PP, Purkayastha S, Lanitis S, Athanasiou T, Heriot AG, Orchard TR, Nicholls RJ, Darzi AW. A comparison of segmental vs subtotal/total colectomy for colonic Crohn's disease: a meta-analysis. Colorectal Dis. 2006;8:82–90. doi: 10.1111/j.1463-1318.2005.00903.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Allan A, Andrews H, Hilton CJ, Keighley MR, Allan RN, Alexander-Williams J. Segmental colonic resection is an appropriate operation for short skip lesions due to Crohn's disease in the colon. World J Surg. 1989;13:611–616. doi: 10.1007/BF01658882. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Longo WE, Ballantyne GH, Cahow CE. Treatment of Crohn's colitis. Segmental or total colectomy? Arch Surg. 1988;123:588–590. doi: 10.1001/archsurg.1988.01400290070011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Martel P, Betton PO, Gallot D, Malafosse M. Crohn's colitis: experience with segmental resections; results in a series of 84 patients. J Am Coll Surg. 2002;194:448–453. doi: 10.1016/s1072-7515(02)01122-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Bernell O, Lapidus A, Hellers G. Recurrence after colectomy in Crohn's colitis. Dis Colon Rectum. 2001;44:647–654. doi: 10.1007/BF02234559. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Andersson P, Olaison G, Bodemar G, Nyström PO, Sjödahl R. Surgery for Crohn colitis over a twenty-eight-year period: fewer stomas and the replacement of total colectomy by segmental resection. Scand J Gastroenterol. 2002;37:68–73. doi: 10.1080/003655202753387383. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Lightner AL. Segmental Resection versus Total Proctocolectomy for Crohn's Colitis: What is the Best Operation in the Setting of Medically Refractory Disease or Dysplasia? Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2018;24:532–538. doi: 10.1093/ibd/izx064. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Fichera A. Laparoscopic treatment of Crohn's disease. World J Surg. 2011;35:1500–1504. doi: 10.1007/s00268-011-1031-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Fichera A, Peng SL, Elisseou NM, Rubin MA, Hurst RD. Laparoscopy or conventional open surgery for patients with ileocolonic Crohn's disease? Surgery. 2007;142:566–571. doi: 10.1016/j.surg.2007.08.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Galata C, Kienle P, Weiss C, Seyfried S, Reißfelder C, Hardt J. Risk factors for early postoperative complications in patients with Crohn's disease after colorectal surgery other than ileocecal resection or right hemicolectomy. Int J Colorectal Dis. 2019;34:293–300. doi: 10.1007/s00384-018-3196-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Umanskiy K, Malhotra G, Chase A, Rubin MA, Hurst RD, Fichera A. Laparoscopic colectomy for Crohn's colitis. A large prospective comparative study. J Gastrointest Surg. 2010;14:658–663. doi: 10.1007/s11605-010-1157-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]