Abstract

HIV self-testing (HIVST) with online real-time counseling (HIVST-online) is an evidence-based intervention to increase HIV testing coverage and to ensure linkage to care for men who have sex with men (MSM). A community-based organization (CBO) recruited 122 MSM who had ever used HIVST-online (ever-users) and another 228 new-users from multiple sources and promoted HIVST-online. A free oral fluid-based HIVST kit was sent to all the participants by mail. Experienced HIVST administrators implemented HIVST-online by providing real-time instruction, standard-of-care pre-test and post-test counseling via live-chat application. The number of HIVST-online sessions performed was documented by the administrators. The post-test evaluation was conducted 6 months after the pre-test survey. At month 6, 63.1% of ever-users and 40.4% of new-users received HIVST-online. Taking other types of HIV testing into account, 79.4% of ever-users and 58.6% of new-users being followed up at month 6 received any HIV testing during the project period. Ever-users were more likely to receive HIVST-online and any HIV testing as compared to new-users. Four HIVST-online users were screened to be HIV positive and linked to the treatment. The process evaluation of HIVST-online was positive. Implementation of HIVST-online was helpful to improve HIV testing coverage and repeated HIV testing among Chinese MSM. A larger scale implementation should be considered.

Keywords: HIV self-testing, online real-time counseling, pilot implementation, outcome and process evaluation, men who have sex with men

1. Introduction

Human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) is a serious public health threat among men who have sex with men (MSM) [1,2,3]. In China, the National Health and Family Planning Commission estimated the overall HIV prevalence among MSM to be 7.7%, and over a quarter of new HIV cases were attributed to MSM [4]. In Hong Kong, the HIV prevalence among MSM was 6.54% in 2017 [5]. MSM accounted for 59.6% of all the reported new HIV cases in 2018 [6].

HIV testing plays a crucial role in the era of “treat all”. Antiretroviral therapy (ART) is highly effective in preventing HIV transmission (over 90%) under conditions of good adherence [7,8,9]. Therefore, the World Health Organization (WHO) recommends ART to all people living with HIV, regardless of their CD4 T cell level [10]. The high coverage of HIV testing among a high-risk population (e.g., MSM) is indispensable to achieve the 90–90–90 targets established by the Joint United Nations Program on HIV/AIDS (i.e., 90% of all people living with HIV know their HIV status, 90% of people with diagnosed HIV receive ART, and 90% of all people on an HIV treatment achieve viral suppression) [11]. With counseling in place, HIV testing and counseling can both detect HIV cases and reduce risk behaviors [12,13]. Therefore, international health authorities recommend MSM to take up HIV testing every 6 months [14,15].

The coverage of HIV testing among MSM was low in Hong Kong. It was estimated that only 80% of HIV-infected MSM were identified in Hong Kong [16]. Very few MSM performed repeated testing (taking up two episodes of HIV testing 6 months apart) as recommended [17]. HIV self-testing (HIVST) is a useful means to increase both the coverage and frequency of HIV testing among MSM [18]. The WHO strongly recommends that HIVST should be offered as an additional approach to existing HIV testing services [19]. At least 77 countries have adopted policies supporting HIVST [20]. In Hong Kong, HIVST kits are available in registered pharmaceutical stores or through online purchase. Starting from 2015, several community-based organizations (CBOs) started to provide HIVST services to MSM. In September 2019, the Hong Kong Department of Health also launched an HIVST program [21]. People can order HIVST kits and upload testing results via an online platform. Most of these existing services provided optional post-test counseling to users. Users can call through a hotline or submit their testing results online to obtain counseling services.

The WHO recommends that pre-test and post-test counseling services should be provided during HIV testing services [22]. There is a concern that HIVST users may skip counseling services. Some researchers argued that the lack of counseling support is a key limitation of HIVST, which might delay linkage to care and treatment [23]. An innovative HIVST service model (HIVST-online) was developed for MSM in Hong Kong, which includes the online promotion of HIVST, delivery of free HIVST kits through mail/express, provision of online real-time instruction, and pre-test/post-test counseling for HIVST users via live chat application. In the pre-test counseling, the administrators assess users’ risk of HIV infection by asking several standard questions (e.g., use of condoms, alcohol/drug during sexual behaviors), inform users on their risk level and explain the rationale. For users at high risk, the administrators prepare them for potential positive testing results. For users without high risk, advices on maintaining safe sex practices are provided. In the end of pre-test counseling, the administrators seek users’ consent to perform HIVST. In the post-test counseling, the administrators interpret the testing results for the participants. For users receiving negative testing results, the administrators explain the window period, provide advices for safe sex practice, and emphasize the needs of regular testing. For users with positive testing results, the administrators provide mental health first aid, information on follow-up services, and facilitate them to receive confirmatory testing in the Department of Health [24]. A randomized controlled trial (RCT) showed that HIVST-online could significantly increase HIV testing uptake [24]. The United States Center for Disease Control and Prevention listed HIVST-online as an evidence-based intervention [25]. However, it is unclear whether HIVST-online is useful to increase repeated HIV testing among MSM.

A CBO having good access to local MSM adapted HIVST-online and started a pilot implementation in January 2017. We evaluated the effectiveness of HIVST-online in increasing HIV testing and repeated testing among MSM in Hong Kong. We compared the uptake of HIVST-online and any HIV testing during a 6-month follow-up period between MSM who were ever-users and new-users of HIVST-online. Indicators of the process evaluation included the level of satisfaction of HIVST-online implementation. In addition, baseline factors predicting the HIVST-online uptake were also investigated.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Design

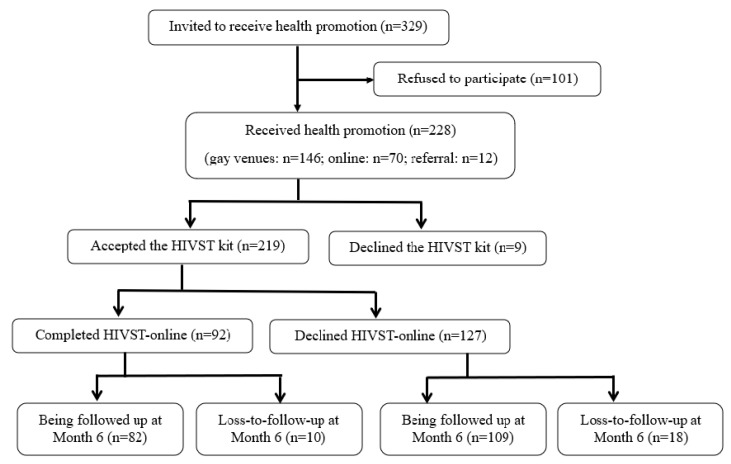

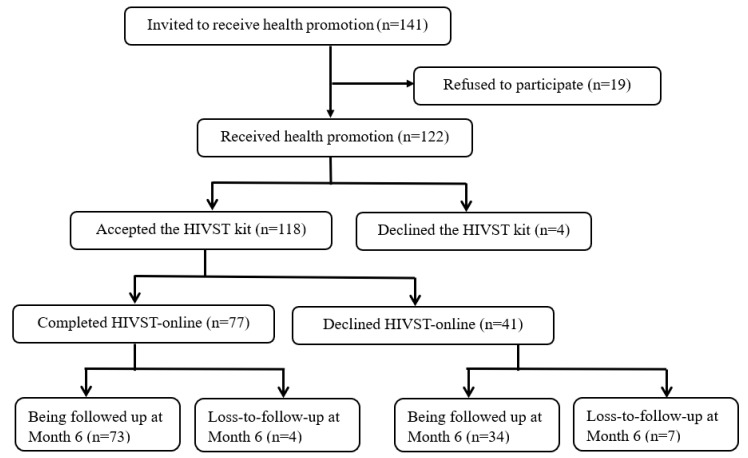

The pilot implementation was conducted from January to December 2017. All participants completed a baseline telephone survey before they received health promotion and implementation of HIVST-online, and completed another telephone survey 6 months after the baseline telephone survey. There was no control or comparison group. The study was registered at ClinicalTrials.gov, number NCT03268564. The flowchart diagram was shown in Figure 1 and Figure 2.

Figure 1.

Flow diagram of the recruitment and uptake of human immunodeficiency virus self-testing (HIVST)-online among new-users.

Figure 2.

Flow diagram of the recruitment and uptake of HIVST-online among ever-users.

2.2. Participants

Inclusion criteria were (1) Hong Kong Chinese speaking males aged ≥18 years old, (2) had anal sex with at least one man in the last 6 months, (3) willing to leave contacts to complete the post-test evaluation, and (4) having access to live-chat applications, e.g., Line (Line Corporation, Tokyo, Japan), Skype (Skype technologies, Microsoft, Palo Alto, CA, USA), or Facetime (Apple Inc., Cupertino, CA, USA). HIV-infected MSM were excluded.

2.3. Recruitment Process

The CBO staff approached MSM in six gay bars and six gay saunas at different time slots on weekdays and at weekends. The CBO staff also conducted online outreach by posting information on the study periodically as discussion topics on two gay websites with the highest traffic in Hong Kong. Interested participants could contact the CBO staff. Recruitment was supplemented by peer referrals. MSM experience a high level of stigma in China and the pre-test/post-test measurements included sensitive topics such as sexual behaviors and history of sexually transmitted infections. The signature on the informed consent document would be the only record linking the participant to the research and the principal risk of harm to the subject would be a breach of confidentiality. Therefore, we sought the endorsement from the Institutional Review Board (IRB) to waive participants’ signature on informed consent documents. Verbal informed consent was obtained according to the IRB guideline [26]. Participants were briefed on the research procedures and before the administration of the data collection, informed that they had the right to terminate the study at any time, and were given an information sheet (either a hardcopy on site or a softcopy through online communication) explaining the purpose, procedures, potential psychological distress caused by HIVST, benefits of joining the program, and their right to end participation at any time. The CBO staff signed a form pledging that the participants had been fully informed about the program. Participants were also briefed on data security. The pledge forms and their contact information were kept separately and stored in a locked cabinet. The participants’ name or contact information would not appear on the questionnaire or in the dataset. Multiple forms of contact information were obtained in order to make an appointment to conduct the pre-test survey and health promotion. Out of 329 MSM who were eligible to join the program, 101 (30.7%) refused to participate since they did not have time and/or for other logistical reasons; 228 (67.3%) participated in the program and received health promotion (gay venues: n = 146; online: n = 70; referral: n = 12) (Figure 1).

In addition, the CBO staff also approached HIVST-online ever-users in the previous RCT [24]. The procedures to obtain informed consent were similar to those for new-users. There were 189 MSM who had used HIVST-online in the previous RCT, the CBO staff was able to contact 141 of them, 19 refused to participate since they did not have time, and 122 provided verbal informed consent to join the program (Figure 2). Therefore, the pilot program covered 350 MSM in Hong Kong, including 228 new-users and 122 ever-users.

2.4. Training of CBO Staff

Eight CBO staff received 14-h basic motivational interviewing (MI) training by an experienced trainer who is a member of the Motivational Interviewing Network of Trainers. They worked as fieldworkers for health promotion. They were trained to deliver MI over the phone to increase their confidence. The role-plays and protocol specific practice were conducted twice a week for 4 weeks, and maintained by coaching sessions every 2 weeks by the same trainer. Fieldworkers were not deployed in the fieldwork unless they achieved an adequate level of competence. Ongoing support and supervision was provided by the trainer. In addition, six CBO staff received a 4-h training workshop on HIVST-online. They worked as HIVST-online administrators in the pilot program.

2.5. Baseline Telephone Survey and Health Promotion

By appointment and through telephone, the CBO staff conducted the 10-min baseline survey. All participants were then sent a link to access the project webpage. The project webpage contained the following health promotion components during the project period:

-

(1)

An online video promoting HIVST-online: The video was used in the previous RCT [24]. In the video, a local MSM narratively discussed the benefits and barriers of HIVST-online, demonstrated its procedures, and emphasized that HIVST was easy to use, as well as the availability of immediate online support.

-

(2)

A new online video promoting regular HIV testing. The video was based on the maintenance theories [27]. In the video, a peer MSM shared his positive experience of using HIVST-online, and emphasized the importance of regular HIV testing.

-

(3)

An online demonstration video on how to use oral fluid-based HIVST kits.

-

(4)

Other health promotion components, including: (i) description of the project, (ii) knowledge and benefit of the HIVST, (iii) information about HIV epidemic among MSM in Hong Kong, (iv) a discussion forum containing positive feedbacks of HIVST-online users, and (v) contact of the program staff (phone, social media, and email).

In addition, new-users received a 15-min MI session over the phone. Fieldworkers made an appointment with the participants to conduct the MI. Ever-users did not receive MI, as they were already motivated to receive the service.

2.6. Implementation of HIVST-Online

The implementation was similar to that of the RCT [24].

(1) Receiving a free oral fluid-based HIVST kit: The HIVST kit used in this study (AwareTM Oral) is the brand of the Calypte Biomedical Corporation in the United States. It has a proven sensitivity/specificity of >99.8% and has been approved for marketing by the State of Food and Drug Administration in China. The kit was available online at a price of about HKD 200 (USD 25.8) during the project period. Unless there is an objection, all the participants were sent a free HIVST kit in a plain envelope without any identification of the program. Participants could also receive the kit sent by express to an address or pick it up in person by mail or express.

(2) Prospective users made appointments with HIVST-online administrators by phone/social media after they have received the HIVST kit.

(3) Through video chat, the administrators explained how to use the HIVST and sent the aforementioned demonstration video to the users if needed. They guaranteed that participants were anonymous and did not need to show their faces if desired and that no taping would be made.

(4) The standard-of-care pre-test counseling was also provided, which covered the knowledge of HIV prevention, risk assessment, and benefits of HIV testing.

(5) Participants performed HIVST, under online and real-time supervision provided by the administrators. It took about 20 min to know the screening results. Users showed the test results visually to the administrators. The standard-of-care post-test counseling was then provided (15–25 min), which covered the following topics: (i) Explanation of the testing results, (ii) reminders for those who received negative results about their risk of HIV infection, and assistance for setting up specific goals for safe-sex behaviors, and (iii) psychological support for those who received positive results, which emphasized that they had to take up a free confirmatory HIV antibody testing offered by the Department of Health. Referrals would be made whenever needed. They could visit the CBO, and CBO staff would accompany them to visit the Department of Health if desired. The entire HIVST-online process took about 60 min, which was comparable to that needed for HIV testing and counseling in CBO or governmental clinics.

2.7. Month 6 Follow-Up Telephone Survey

Participants were invited to complete a follow-up telephone survey 6 months after the baseline survey. Up to five calls were made at different timeslots during weekdays/weekends before considering a case as loss-to-follow-up. A total of 191 (83.8%) new-users and 107 (87.7%) ever-users completed the follow-up survey.

2.8. Measurements

2.8.1. Primary Outcome

The primary outcome is whether the participant has taken up HIVST-online between the baseline and follow-up surveys during a 6-month follow-up period. This outcome was recorded by HIVST-online administrators. At month 6, participants were also asked whether they received other forms of HIV testing during the follow-up period.

2.8.2. Baseline Background Characteristics

Information collected included socio-demographics, sexual orientation, utilization of HIV/STI prevention services, history of HIV and other STIs, smoking, and drinking. Queried sexual behaviors included anal intercourse with regular and non-regular sex partners, condomless anal intercourse (CAI) with men, multiple male sex partnerships, use of sexual potency drugs, and engagement in sexualized drug use in the past 6 months. Regular male sex partners (RP) were defined as lovers and/or stable boyfriends, while non-regular partners (NRP) were defined as causal sex partners and/or male sex workers. In this study, sexualized drug use was defined as the use of any psychoactive substance before or during sexual intercourse [28].

2.8.3. Perceptions Related to HIVST Measured at the Baseline

Six scales were constructed based on the Health Belief Model (HBM) [29]. They were: (1) The two-item Perceived Logistical Benefit Scale, (2) the three-item Perceived Psychological Benefit Scale, (3) the four-item Perceived Logistical Barrier Scale, (4) the four-item Perceived Psychological Barrier Scale, (5) the two-item Cue to Action Scale, and (6) the four-item Perceived Self-Efficacy Scale. The response categories for these scales were 1 = strongly disagree, 2 = disagree, 3 = neutral, 4 = agree, and 5 = strongly agree. The Cronbach’s alpha of these scales ranged from 0.64 to 0.89, single factors were identified by the exploratory factor analysis, explaining 48.3–89.9% of the total variance.

In addition, two single items measured the behavioral intention to take up HIVST-online in the next 6 months (response categories: 1 = unlikely, 2 = neutral, 3 = likely) and perceived importance of real-time counseling supporting HIVST users (1 = very unimportant, 2 = unimportant, 3 = neutral, 4 = important, 5 = very important).

2.8.4. Process Evaluation

The fieldworkers recorded the starting/ending time of the MI as verification. The HIVST administrator kept a log sheet for each user to ensure key steps of the pre-test and post-test counseling were completed.

The process evaluation of health promotion and HIVST-online implementation was conducted at month 6. Participants were asked: (1) Whether the content of the online video was clear, (2) whether the content of the online video was attractive, (3) whether they were satisfied with the project webpage, and (4) whether the health promotion had increased their understanding on the importance of regular HIV testing and their willingness to take up HIV testing. New-users were asked an additional question about their satisfaction of the MI session. HIVST-online users were asked about the satisfaction of the logistics of implementation and performance of the HIVST-online administrators.

2.9. Ethics Statement

All subjects gave their informed consent for inclusion before they participated in the study. The study was approved by the Survey and Behavioral Research Ethics Committee, the Chinese University of Hong Kong (reference: KPF16ICF10).

2.10. Statistical Analysis

The difference in baseline characteristics between new-users and ever-users, and between those who declined and who received HIVST-online at month 6 were compared using X2 tests or independent sample t-tests. Logistic regression models were used to test the between-group differences in the uptake of HIVST-online and any HIV testing, after controlling any baseline variables that showed p < 0.05 in between-group comparisons. Crude odds ratios (OR) and adjusted odds ratios (AOR) were obtained. Baseline characteristics of participants who completed the month 6 post-test survey and those who were lost-to-follow-up were also compared. Using the HIVST-online uptake during the follow-up period as the dependent variable, and baseline background characteristics as an independent variable, OR predicting that the dependent variable were obtained using logistic regression models. After adjustment for those variables with p < 0.05 in the univariate analysis, the association between perceptions related to HIVST and the dependent variable were then assessed by AOR. Each AOR was obtained by fitting a single logistic regression model, which involved one of the perceptions and the significant background variables. SPSS version 21.0 (Chicago, IL, USA) was used for data analysis and p-values < 0.05 were considered as statistically significant.

3. Results

3.1. Baseline Characteristics

Over half of the participants were aged 18–30 years (57.1%), currently single (83.1%), had attended at least a college education (86.6%), full-time employed (84.3%), and identified themselves as gay (93.1%). In the past 3 months, 70% and 45.1% had anal intercourse with RP and NRP. The prevalence of multiple male sex partnerships, CAI with men, and sexualized drug use was 43.7%, 35.1%, and 3.4% in the past 3 months, respectively. Regarding the history of HIV testing, 38.6% received more than three episodes of HIV testing in addition to HIVST-online in the past 3 years. Item responses and scale scores of perceptions related to HIVST were shown in Table 1.

Table 1.

Background characteristics of the participants.

| All (n = 350) |

New-Users of HIVST-Online (n = 228) | Ever-Users of HIVST-Online (n = 122) | p-Value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| % | % | % | ||

| Socio-demographic characteristics | ||||

| Age group (years) | ||||

| 18–30 | 57.1 | 54.4 | 62.3 | |

| 31–40 | 31.4 | 34.6 | 25.4 | |

| >40 | 11.4 | 11.0 | 12.3 | 0.21 |

| Marital/cohabitation status | ||||

| Currently single | 83.1 | 79.4 | 90.2 | |

| Cohabitate/married with a man | 16.6 | 20.6 | 9.0 | |

| Cohabited/married with a woman | 0.3 | 0 | 0.8 | 0.01 |

| Highest education level attained | ||||

| Secondary or below | 13.4 | 12.7 | 14.8 | |

| College or above | 86.6 | 87.3 | 85.2 | 0.60 |

| Current employment status | ||||

| Full-time | 84.3 | 86.0 | 81.1 | |

| Part-time/unemployed/retired/student | 15.7 | 14.0 | 18.9 | 0.24 |

| Sexual orientation | ||||

| Gay | 93.1 | 93.4 | 92.6 | |

| Bisexual | 6.3 | 5.7 | 7.4 | |

| Heterosexual | 0.6 | 0.9 | 0 | 0.49 |

| History of sexually transmitted infection | ||||

| No | 79.1 | 74.1 | 87.7 | |

| Yes | 20.9 | 25.4 | 12.3 | 0.004 |

| HIV testing history | ||||

| No. of HIV testing in the past 3 years in addition to HIVST-online | ||||

| 0 | 17.4 | 16.2 | 19.7 | |

| 1–3 | 44.0 | 38.6 | 54.1 | |

| >3 | 38.6 | 45.2 | 26.2 | 0.002 |

| Sexual behaviors in the last 3 months | ||||

| Anal intercourse with regular male sex partner(s) (RP) | ||||

| No | 30.0 | 25.9 | 36.9 | |

| Yes | 70.0 | 74.1 | 62.3 | 0.02 |

| Anal intercourse with non-regular male sex partner(s) (NRP) | ||||

| No | 54.6 | 57.0 | 50.0 | |

| Yes | 45.1 | 43.0 | 49.2 | 0.24 |

| Condomless anal intercourse (CAI) with men | ||||

| No | 54.9 | 57.0 | 50.8 | |

| Yes | 35.1 | 34.6 | 36.1 | 0.52 |

| Multiple male sex partnerships | ||||

| No | 56.3 | 59.2 | 50.8 | |

| Yes | 43.7 | 40.8 | 49.2 | 0.13 |

| Illicit drug use before/during anal intercourse with men | ||||

| No | 96.6 | 96.5 | 96.7 | |

| Yes | 3.4 | 3.5 | 3.3 | 0.91 |

| Perceptions related to HIV testing | ||||

| Behavioral intention to use free HIVST with real-time counseling services in the coming 6 months | ||||

| Unlikely/neutral | 25.7 | 26.3 | 24.6 | |

| Likely | 74.3 | 73.7 | 75.4 | 0.73 |

| Perceived logistical benefits of HIVST (% agree/strongly agree) | ||||

| HIVST is easy for you to use | 76.0 | 74.1 | 79.5 | |

| HIVST is convenient for you | 82.3 | 81.6 | 83.6 | |

| Perceived Logistical Benefit Scale 1 (Mean/SD) | 8.1/1.6 | 7.9/1.5 | 8.4/1.8 | 0.01 |

| Perceived psychological benefits of HIVST (% agree/strongly agree) | ||||

| Using HIVST could reduce embarrassment | 79.1 | 77.6 | 82.0 | |

| Using HIVST could avoid being stigmatized by service providers | 50.0 | 42.5 | 63.9 | |

| Using HIVST could protect your privacy | 84.0 | 82.0 | 87.7 | |

| Perceived Psychological Benefit Scale 2 (Mean/SD) | 11.5/2.6 | 10.9/2.6 | 12.4/2.4 | <0.001 |

| Perceived logistical barriers of HIVST (% agree/strongly agree) | ||||

| HIVST is expensive for you | 57.1 | 59.6 | 52.5 | |

| It is difficult for you to buy a HIVST kit | 54.0 | 51.8 | 58.2 | |

| You do not know how to choose a reliable HIVST kit | 70.0 | 69.3 | 71.3 | |

| You are concerned about the accuracy of HIVST | 53.4 | 57.9 | 45.1 | |

| Perceived Logistical Barrier Scale 3 (Mean/SD) | 14.0/3.2 | 13.9/3.2 | 14.2/3.2 | 0.33 |

| Perceived psychological barrier of HIVST (% agree/strongly agree) | ||||

| You are not psychologically prepared to perform HIVST | 19.4 | 17.1 | 23.8 | |

| You are concerned about not understanding the HIVST results | 13.1 | 13.2 | 13.1 | |

| You cannot receive immediate psychological support if you have a positive HIVST result | 40.3 | 35.1 | 50.0 | |

| You cannot access the HIV treatment and care services if you have a positive HIVST result | 27.1 | 24.6 | 32.0 | |

| Perceived Psychological Barrier Scale 4 (Mean/SD) | 10.6/3.1 | 10.0/3.1 | 11.6/2.7 | <0.001 |

| Cue to action related to HIVST (% agree/strongly agree) | ||||

| Significant others will support you to do HIVST | 70.3 | 68.4 | 73.8 | |

| Male sex partner will support you to do HIVST | 78.9 | 79.4 | 77.9 | |

| Cue to Action Scale 5 (Mean/SD) | 7.9/1.6 | 7.8/1.5 | 8.1/1.9 | 0.05 |

| Perceived self-efficacy related to HIVST (% agree/strongly agree) | ||||

| You are confident to obtain a high-quality HIVST kit | 38.0 | 39.9 | 34.4 | |

| You are confident to use HIVST kits properly | 74.0 | 73.7 | 74.6 | |

| You are confident to understand the HIVST results | 78.6 | 79.4 | 77.0 | |

| You are confident to receive confirmatory testing after obtaining a positive HIVST result | 78.3 | 80.7 | 73.8 | |

| Perceived Self-efficacy Scale 6 (Mean/SD) | 14.8/2.4 | 14.8/2.4 | 14.9/2.4 | 0.63 |

| Perceived importance of real-time counseling service supporting HIVST users | ||||

| Very unimportant/ unimportant/neutral | 36.0 | 38.6 | 31.1 | |

| Important/very important | 64.0 | 61.4 | 68.9 | 0.17 |

p-values were obtained using the X2 test (for categorical variables) or independent-sample t-tests (for continuous variables); 1 Perceived Logistical Benefit Scale, two items, Cronbach’s alpha = 0.89, one factor was identified by the exploratory factor analysis, explaining 89.9% of total variance; 2 Perceived Psychological Benefit Scale, three items, Cronbach’s alpha = 0.72, one factor was identified by the exploratory factor analysis, explaining 66% of total variance; 3 Perceived Logistical Barrier Scale, four items, Cronbach’s alpha = 0.67, one factor was identified by the exploratory factor analysis, explaining 51.4% of total variance; 4 Perceived Psychological Barrier Scale, four items, Cronbach’s alpha = 0.64, one factor was identified by the exploratory factor analysis, explaining 48.3% of total variance; 5 Cue to Action Scale, two items, Cronbach’s alpha = 0.84, one factor was identified by the exploratory factor analysis, explaining 86.6% of total variance; 6 Perceived Self-efficacy Scale, four items, Cronbach’s alpha = 0.67, one factor was identified by the exploratory factor analysis, explaining 53.4% of total variance.

As compared to ever-users of HIVST-online, new-users were more likely to be cohabited/married with a man (p = 0.01), with a history of STI (p = 0.004), had received more than three episodes of HIV testing in addition to HIVST-online (p = 0.002), reported anal intercourse with RP in the past 3 months (p = 0.02), and scored higher in the Perceived Logistical Benefit Scale (p = 0.01), the Perceived Psychological Benefit Scale (p < 0.001), and the Perceived Psychological Barrier Scale (p < 0.001).

When comparing those who were followed up and were lost to follow-up, a significant difference was found in perceived logistical benefits among new-users (p = 0.02) and perceived importance of real-time counseling service supporting HIVST among ever-users (p = 0.01) (Table S1).

3.2. HIV Testing Uptake during the Follow-Up Period

As documented by the HIVST administrators, 40.4% (92/228) of new-users and 63.1% (77/122) of ever-users received HIVST-online during the project period. Among the participants who were followed up at month 6, 58.6% (112/191) and 79.4% (85/107) used any HIV testing during the follow-up period. As compared to new-users, ever-users were more likely to receive HIVST-online (AOR: 3.01, 95% CI: 1.80, 5.05) and any HIV testing (AOR: 4.82, 95% CI: 2.51–9.28) (Table 2).

Table 2.

Types of HIV testing taken up by the participants during the follow-up period.

| All | New-Users of HIVST-Online |

Ever-Users of HIVST-Online | Ever-Users vs. New-Users | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| % | % | % | |||||

| Among All Participants (n = 350) | n = 350 | n = 228 | n = 122 | OR (95%CI) | p-Value | AOR (95%CI) | p-Value |

| HIVST-online uptake as documented by the HIVST-administrators (% Yes) | 48.3 | 40.4 | 63.1 | 2.53 (1.61–3.98) | <0.001 | 3.01 (1.80–5.05) | <0.001 |

| Among participants who completed the month 6 post-test survey (n = 298) | n = 298 | n = 191 | n = 107 | OR (95%CI) | p-value | AOR (95%CI) | p-value |

| Uptake of other types of HIV testing reported by the participants at the post-test survey (% Yes) | |||||||

| Using HIVST kits obtained in the project without receiving online real-time counseling services | 1.0 | 0.5 | 1.9 | 3.62 (0.32–40.39) | 0.30 | 13.99 (0.86–226.91) | 0.06 |

| Self-purchased HIVST kits and used by themselves | 0.7 | 1.0 | 0 | N.A. | N.A. | N.A. | N.A. |

| HIV testing at governmental hospitals or clinics | 5.0 | 4.7 | 5.6 | 1.20 (0.42–3.47) | 0.74 | 1.54 (0.46–5.19) | 0.48 |

| HIV testing at non-governmental organizations (NGO) | 21.1 | 20.9 | 21.5 | 1.03 (0.58–1.84) | 0.91 | 2.43 (1.16–5.07) | 0.02 |

| HIV testing at private clinics/laboratories | 1.3 | 0.5 | 2.8 | 5.48 (0.56–53.36) | 0.14 | 4.47 (0.40–50.16) | 0.23 |

| Any type of HIV testing | 66.1 | 58.6 | 79.4 | 2.73 (1.57–4.73) | <0.001 | 4.82 (2.51–9.28) | <0.001 |

OR: Crude odds ratios; AOR: Adjusted odds ratios, odds ratios adjusted for baseline variables with p < 0.05 in between-group comparisons in Table 1.

Four HIVST-online users were screened to be HIV positive. Facilitated by the administrators, all of them received confirmatory HIV testing in the Department of Health and confirmed to be HIV positive. All of them received the appropriate treatment and care services.

3.3. Factors Predicting HIVST-Online Uptake

Being ever-users of HIVST-online at the baseline was associated with higher uptake of HIVST-online during the follow-up period (OR: 2.53, 95% CI: 1.61, 3.98) in the univariate analysis (Table 3). The behavioral intention to take up HIVST-online at the baseline was also associated with higher uptake of HIVST-online in the univariate analysis (OR: 1.67, 95% CI: 1.03, 2.72) but not in the adjusted analysis (Table 4).

Table 3.

Baseline background variables predicting the uptake of HIVST-online (n = 350).

| OR (95% CI) | p-Value | |

|---|---|---|

| Socio-demographic characteristics | ||

| Age group (years) | ||

| 18–30 | 1.0 | |

| 31–40 | 1.31 (0.84–2.12) | 0.23 |

| >40 | 0.85 (0.43–1.69) | 0.64 |

| Marital/cohabitation status | ||

| Currently single | 1.0 | |

| Cohabitate/married with a man | 0.60 (0.34–1.07) | 0.08 |

| Cohabited/married with a woman | N.A. | N.A. |

| Highest education level attained | ||

| Secondary or below | 1.0 | |

| College or above | 0.80 (0.43–1.48) | 0.47 |

| Current employment status | ||

| Full-time | 1.0 | |

| Part-time/unemployed/retired/student | 0.67 (0.37–1.21) | 0.18 |

| Sexual orientation | ||

| Gay | 1.0 | |

| Bisexual | 0.48 (0.19–1.20) | 0.12 |

| Heterosexual | 1.03 (0.06–16.52) | 0.99 |

| History of sexually transmitted infection | ||

| No | 1.0 | |

| Yes | 0.79 (0.47–1.33) | 0.38 |

| HIV testing history | ||

| Number of HIV testing in the past 3 years | ||

| 0 | 1.0 | |

| 1–3 | 0.99 (0.55–1.80) | 0.99 |

| >3 | 1.07 (0.58–1.96) | 0.82 |

| Being new-users or ever-users of HIVST-online | ||

| New-users | 1.0 | |

| Ever-users | 2.53 (1.61–3.98) | <0.001 |

| Sexual behaviors in the last 3 months | ||

| Anal intercourse with regular male sex partner(s) (RP) | ||

| No | 1.0 | |

| Yes | 0.71 (0.45–1.12) | 0.14 |

| Anal intercourse with non-regular male sex partner(s) (NRP) | ||

| No | 1.0 | |

| Yes | 1.42 (0.93–2.16) | 0.11 |

| Condomless anal intercourse (CAI) with men | ||

| No | 1.0 | |

| Yes | 1.28 (0.82–2.02) | 0.28 |

| Multiple male sex partnerships | ||

| No | 1.0 | |

| Yes | 1.27 (0.83–1.94) | 0.27 |

| Illicit drug use before/during anal intercourse with men (sexualized drug use) | ||

| No | 1.0 | |

| Yes | 1.52 (0.47–4.89) | 0.48 |

OR: Crude odds ratios.

Table 4.

Factors predicting the uptake of HIVST-online (n = 350).

| OR (95% CI) | p-Value | AOR (95% CI) | p-Value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Perceived Logistical Benefit Scale | 1.00 (0.88–1.14) | 0.95 | 0.98 (0.84–1.15) | 0.82 |

| Perceived Psychological Benefit Scale | 1.01 (0.93–1.09) | 0.91 | 0.99 (0.91–1.09) | 0.91 |

| Perceived Logistical Barrier Scale | 1.03 (0.96–1.10) | 0.39 | 1.03 (0.96–1.11) | 0.39 |

| Perceived Psychological Barrier Scale | 1.00 (0.93–1.07) | 0.96 | 0.99 (0.91–1.07) | 0.74 |

| Cue to Action Scale | 0.98 (0.86–1.12) | 0.78 | 0.98 (0.84–1.13) | 0.74 |

| Perceived Self-efficacy Scale | 1.01 (0.92–1.10) | 0.91 | 1.01 (0.91–1.11) | 0.89 |

| Perceived importance of real-time counseling supporting HIVST users | ||||

| Very unimportant/unimportant/neutral | 1.0 | 1.0 | ||

| Important /very important | 1.48 (0.95–2.30) | 0.08 | 1.40 (0.88–2.21) | 0.15 |

| Behavioral Intention to take up free HIVST in the coming 6 months | ||||

| Unlikely/neutral | 1.0 | 1.0 | ||

| Likely | 1.67 (1.03–2.72) | 0.04 | 1.60 (0.95–2.69) | 0.08 |

OR: Crude odds ratios; AOR: Adjusted odds ratios, odds ratios adjusted for being new-users or ever-users of HIVST-online.

3.4. Process Evaluation of HIVST-Online Users

As recorded by the fieldworkers, the duration of MI ranged from 11 to 19 min. All HIVST-online administrators closely followed the protocol. Among the HIVST-online users who completed the process evaluation (n = 125), 88.8–96.8% were satisfied/very satisfied with different procedures of HIVST-online, 72.0–97.6% believed that the online real-time counseling was helpful in different aspects such as understanding their current risk, testing results, concept of window period, and reducing their fear toward HIV testing and high-risk behaviors (Table 5).

Table 5.

Process evaluation of HIVST-online users (among those being followed up at month 6, n = 125).

| All (n = 125) | New-Users of HIVST-online (n = 58) | Ever-Users of HIVST-online (n = 67) | p-Value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| % | % | % | ||

| Level of satisfaction of different procedures of HIVST-online (% satisfied/very satisfied) | ||||

| Receiving HIVST kits | 92.0 | 89.7 | 94.0 | 0.37 |

| Making appointment of HIVST-online | 96.0 | 98.3 | 94.0 | 0.23 |

| Visual and sound quality of online counseling | 92.8 | 96.6 | 89.6 | 0.13 |

| Clarity of instruction | 96.8 | 98.3 | 95.5 | 0.38 |

| Professionalism of HIVST-administrators | 96.8 | 100.0 | 94.0 | 0.06 |

| Credibility of HIVST-administrators | 96.8 | 98.3 | 95.5 | 0.38 |

| Support from HIVST-online administrators | 92.8 | 96.6 | 89.6 | 0.13 |

| Recommendations made by HIVST-online administrators on reducing high-risk behaviors | 88.8 | 89.7 | 88.1 | 0.99 |

| How helpful is online real-time counseling in the following aspects | ||||

| Understanding your current risk of HIV infection | 85.6 | 82.8 | 88.1 | 0.40 |

| Reducing your fear of HIV testing | 72.0 | 65.5 | 77.6 | 0.13 |

| Preparing you to do HIV testing | 78.4 | 72.2 | 83.6 | 0.13 |

| Mastering the methods and procedures of HIVST | 96.0 | 94.8 | 97.0 | 0.53 |

| Understanding testing results | 97.6 | 98.3 | 97.0 | 0.65 |

| Understanding the concept of window period | 88.8 | 87.9 | 89.6 | 0.77 |

| Acquiring knowledge to prevent HIV infection | 85.6 | 87.9 | 83.6 | 0.49 |

| Reducing high-risk behaviors | 80.0 | 81.0 | 79.1 | 0.79 |

| Behavioral intention to use HIVST-online again | ||||

| Very unlikely/unlikely/neutral | 21.6 | 24.1 | 19.4 | |

| Likely/very likely | 78.4 | 75.9 | 80.6 | 0.52 |

| Behavioral intention to recommend MSM friends to use HIVST-online | ||||

| Very unlikely/unlikely/neutral | 23.2 | 27.6 | 19.4 | |

| Likely/very likely | 76.8 | 72.4 | 80.6 | 0.28 |

p-value was obtained by using the χ2 test.

3.5. Baseline Characteristics between Those Who Declined and Received HIVST-Online

When comparing those who declined HIVST-online to those who received HIVST-online, a significant difference was found in the behavioral intention to use the free HIVST-online with real-time counseling services in the coming 6 months (p = 0.02). No significant difference was found in the other characteristics (Table S2).

4. Discussion

Our results showed that implementing HIVST-online is helpful in increasing HIV testing coverage among MSM in Hong Kong. The proportion of MSM who had taken up any type of HIV testing in our project (66.1%) was higher than that of a multimedia campaign promoting HIV testing in Hong Kong (43.1%) [30]. The prevalence of HIVST uptake in our project (48.3%) was comparable to a successful social entrepreneurship HIVST service model in Southern China (46.8%) [31]. There is also room to improve the effectiveness of the health promotion for HIVST-online. The current health promotion for HIVST-online was standard and one-off. The meta-analysis showed that interventions tailored to one’s stage of change are more effective than non-stage-tailored, especially among less-motivated individuals (e.g., new-users) [32]. In addition, studies showed that people might move forward to the later SOC, go backward to the earlier SOC, or stay in the same SOC after being exposed to health promotion [33]. Therefore, it is highly recommended that stage-tailored interventions should have multiple sessions and each session should tailor to the people’s current SOC [34]. Future programs should explore the effectiveness of applying multiple sessions of stage-tailored interventions to promote HIVST-online. In addition, about 20% of new-users and ever-users used other forms of HIV testing rather than HIVST-online. Future programs should also consider linking MSM to other forms of HIV testing at the same time (e.g., HIV testing at CBO), as some of them may not prefer HIVST-online.

It is encouraging to observe that about 80% of HIVST-online ever-users received any HIV testing during the project period, and the majority of them used HIVST-online again. Therefore, implementation of HIVST-online is of good potential to increase the regular HIV testing rate, which is very low among Chinese MSM [17]. Regular HIV testing is important for MSM as their sexual risk behaviors are continuous.

According to the process evaluation results shown in Table 5, 65.5–98.3% of new-users and 77.6–97.0% of ever-testers of HIVST-online believed the counseling service supporting HIVST users to be important. HIVST-online users were satisfied with the real-time counseling. With real-time counseling in place, administrators know all the users’ sero-status and provide immediate support to the users. This is especially important to facilitate those who received positive HIVST results to receive confirmatory testing, treatment, and care. In our project, all the users who received positive HIVST results received immediate support and were linked to care and treatment. In contrast, only 55% of HIVST service users would seek a confirmatory test in a clinic if they got an HIV-positive test in previous studies [35]. Ensure linkage to care is one major strength of HIVST-online.

Based on the findings presented in Table 3 and Table 4, being ever-users and having a behavioral intention to use HIVST at the baseline predicted the HIVST-online uptake during the project period, while the associations between HIVST-online uptakes and other background variables or baseline perceptions were non-significant. Such non-significant findings also had some implications. MSM with different socio-demographic, behavioral characteristics, and perceptions responded positively and similarly to the HIVST-online promotion.

This study has the strengths of a low drop-out rate, validated primary outcome, and good process evaluation. However, it also has several limitations. First, there was no control group, since HIVST-online had already been evaluated by RCT. The aim of this study was to evaluate its effectiveness in real-world settings rather than its efficacy. Second, the uptake of other types of HIV testing was self-reported and was likely to be over-reported due to social desirability. Third, a selection bias might exist, as we did not collect information of the MSM who refused to join the study. They may have different characteristics as compared to the participants. Fourth, an attrition bias might also exist. However, this should be small as the drop-out rate is low. Finally, this study used convenience sampling, since probability sampling was not feasible. In addition, a selection bias existed. Therefore, cautions should be taken when generalizing the results to the MSM in Hong Kong or other Chinese cities.

5. Conclusions

The implementation of HIVST-online was helpful in increasing the HIV testing rate among MSM and ensure good linkage to care among HIVST users in Hong Kong. It is also of good potential to increase regular HIV testing. A larger scale implementation should be considered.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to express their gratitude to all the participants for their engagement in this study.

Supplementary Materials

The following are available online at https://www.mdpi.com/1660-4601/18/2/729/s1. Table S1: Comparing baseline characteristics of participants who completed the follow-up evaluation at month 6 versus those who were lost at follow-up; Table S2. Comparing baseline characteristics of participants who declined HIVST-online and completed HIVST-online at Month 6 follow-up.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, Z.W. and J.T.F.L.; methodology, Z.W., J.T.F.L., A.C., and J.L.; validation, Z.W. and J.T.F.L.; data curation, Z.W. and P.S.-f.C.; formal analysis, Z.W. and P.S.-f.C.; investigation, Z.W., J.T.F.L., and P.S.-f.C.; project administration, A.C., J.L., and M.I.; resources, A.C., J.L., and M.I.; supervision, Z.W. and J.T.F.L.; writing—original draft preparation, P.S.-f.C., Z.W., A.C., J.L., M.I., and J.T.F.L.; writing—review and editing, P.S.-f.C. and Z.W.; funding acquisition, Z.W. and J.T.F.L. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by the Knowledge Transfer Project Fund, The Chinese University of Hong Kong, grant number KPF16ICF10.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted according to the guidelines of the Declaration of Helsinki, and approved by the Institutional Review Board of The Chinese University of Hong Kong (protocol code: KPF16ICF10 and date of approval: 13 February 2017).

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

Data are contained within the article or supplementary materials.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Footnotes

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Beyrer C., Baral S.D., Walker D., Wirtz A.L., Johns B., Sifakis F. The expanding epidemics of HIV type 1 among men who have sex with men in low- and middle-income countries: Diversity and consistency. Epidemiol. Rev. 2010;32:137–151. doi: 10.1093/epirev/mxq011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Li X., Lu H., Cox C., Zhao Y., Xia D., Sun Y., He X., Xiao Y., Ruan Y., Jia Y., et al. Changing the landscape of the HIV epidemic among MSM in China: Results from three consecutive respondent-driven sampling surveys from 2009 to 2011. Biomed Res. Int. 2014;2014:563517. doi: 10.1155/2014/563517. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Sullivan P.S., Jones J.S., Baral S.D. The global north: HIV epidemiology in high-income countries. Curr. Opin. HIV AIDS. 2014;9:199–205. doi: 10.1097/COH.0000000000000039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.National Health and Family Planning Commission of the People’s Republic of China China AIDS Response Progress Report. [(accessed on 20 February 2020)];2015 Available online: https://www.unaids.org/sites/default/files/country/documents/CHN_narrative_report_2015.pdf.

- 5.Hong Kong Department of Health PRiSM—HIV Prevalence and Risk Behavioural Survey of Men Who Have Sex with Men in Hong Kong 2017. [(accessed on 15 February 2020)]; Available online: https://www.aids.gov.hk/english/surveillance/sur_report/prism2017e.pdf.

- 6.Hong Kong Department of Health HIV Surveillance Report—2018 Update. [(accessed on 10 February 2020)]; Available online: https://www.aids.gov.hk/english/surveillance/sur_report/hiv18.pdf.

- 7.Anglemyer A., Rutherford G.W., Horvath T., Baggaley R.C., Egger M., Siegfried N. Antiretroviral therapy for prevention of HIV transmission in HIV-discordant couples. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2013;4:CD009153. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD009153.pub3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Tanser F., Barnighausen T., Grapsa E., Zaidi J., Newell M.L. High coverage of ART associated with decline in risk of HIV acquisition in rural KwaZulu-Natal, South Africa. Science. 2013;339:966–971. doi: 10.1126/science.1228160. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Baeten J.M., Donnell D., Ndase P., Mugo N.R., Campbell J.D., Wangisi J., Tappero J.W., Bukusi E.A., Cohen C.R., Katabira E., et al. Antiretroviral prophylaxis for HIV prevention in heterosexual men and women. N. Engl. J. Med. 2012;367:399–410. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1108524. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.World Health Organization (WHO) Guideline on When to Start Antiretroviral Therapy and on Pre-Exposure Prophylaxis for HIV. [(accessed on 20 February 2020)];2015 Available online: https://www.who.int/hiv/pub/guidelines/earlyrelease-arv/en/ [PubMed]

- 11.UNAIDS An Ambitious Treatment Target to Help End the AIDS Epidemic. [(accessed on 16 February 2020)];2014 Available online: http://www.unaids.org/sites/default/files/media_asset/90-90-90_en_0.pdf.

- 12.Hao C., Huan X., Yan H., Yang H., Guan W., Xu X., Zhang M., Wang N., Tang W., Gu J., et al. A randomized controlled trial to evaluate the relative efficacy of enhanced versus standard voluntary counseling and testing on promoting condom use among men who have sex with men in China. AIDS Behave. 2012;16:1138–1147. doi: 10.1007/s10461-012-0141-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Rotheram-Borus M.J., Newman P.A., Etzel M.A. Effective detection of HIV. J. Acquir. Immune Defic. Syndr. 2000;25:S105–S114. doi: 10.1097/00126334-200012152-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.World Health Organization (WHO) UNAIDS Guidance on Provider-Initiated HIV Testing and Counselling in Health Facilities (Strengthening Health Services for Fight HIV/AIDS) [(accessed on 10 February 2020)];2007 Available online: http://www.who.int/hiv/pub/guidelines/9789241595568_en.pdf.

- 15.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) HIV testing among men who have sex with men–21 cities, United States. Morb. Mortal. Wkly. Rep. 2011;60:694. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hong Kong Advisory Council on AIDS Recommended HIV/AIDS Strategies for Hong Kong (2017–2021) [(accessed on 13 April 2020)]; Available online: http://www.aca.gov.hk/english/strategies/pdf/strategies17-21.pdf.2017.

- 17.Gu J., Lau J.T., Wang Z., Wu A.M., Tan X. Perceived empathy of service providers mediates the association between perceived discrimination and behavioral intention to take up HIV antibody testing again among men who have sex with men. PLoS ONE. 2015;10:e0117376. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0117376. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Johnson C., Kennedy C., Fonner V., Siegfried N., Figueroa C., Dalal S., Sands A., Baggaley R. Examining the effects of HIV self-testing compared to standard HIV testing services: A systematic review and meta-analysis. J. Int. AIDS Soc. 2017;20:21594. doi: 10.7448/IAS.20.1.21594. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.World Health Organization The WHO Guideline on HIV Self-Testing and Partner Notification. [(accessed on 15 April 2020)];2016 Available online: http://www.who.int/hiv/pub/vct/hiv-self-testing-guidelines/en/

- 20.World Health Organization HIV Self-Testing. [(accessed on 11 February 2020)];2019 Available online: https://www.who.int/hiv/topics/self-testing/en/

- 21.Department of Health HIV Self-Testing. [(accessed on 11 February 2020)]; Available online: https://dh-hivst.com.hk/en.

- 22.World Health Organization HIV Testing and Counselling: The Gateway to Treatment, Care and Support. [(accessed on 6 August 2020)];2003 Available online: https://www.who.int/3by5/publications/briefs/hiv_testing_counselling/en/

- 23.Katz D.A., Cassels S.L., Stekler J.D. Response to the modeling analysis by Katz et al. on the impact of replacing clinic-based HIV tests with home testing among men who have sex with men in Seattle: Authors’ reply. Sex Transm. Dis. 2014;41:320. doi: 10.1097/OLQ.0000000000000131. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Wang Z., Lau J., Ip M., Ho S.P.Y., Mo P.K.H., Latkin C., Ma Y.L., Kim Y. A randomized controlled trial evaluating efficacy of promoting a home-based HIV self-testing with online counseling on increasing HIV testing among men who have sex with men. AIDS Behave. 2018;22:190–201. doi: 10.1007/s10461-017-1887-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Center for Disease Control and Prevention Home-Based HIV Self-Testing with Online Instruction and Counseling (HIVST-OIC) [(accessed on 23 July 2020)]; Available online: https://www.cdc.gov/hiv/pdf/research/interventionresearch/compendium/si/cdc-hiv-Home_Based_HIV_Self_Testing_Online_SI_EBI.pdf.

- 26.The Chinese University of Hong Kong Guidelines for Survey and Behavioral Research Ethics. [(accessed on 23 November 2020)]; Available online: https://www.orkts.cuhk.edu.hk/images/Research_Funding/SBRE_appguide_Aug_2018.pdf.

- 27.Prochaska J.O., Redding C.A., Harlow L.L., Rossi J.S., Velicer W.F. The transtheoretical model of change and HIV prevention: A review. Health Educ. Q. 1994;21:471–486. doi: 10.1177/109019819402100410. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Wang Z., Yang X., Mo P.K.H., Fang Y., Ip T.K.M., Lau J.T.F. Influence of Social Media on Sexualized Drug Use and Chemsex Among Chinese Men Who Have Sex With Men: Observational Prospective Cohort Study. J. Med. Internet Res. 2020;22:e17894. doi: 10.2196/17894. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Janz N.K., Becker M.H. The Health Belief Model: A decade later. Health Educ. Q. 1984;11:1–47. doi: 10.1177/109019818401100101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Kwan N., Wong A., Fang Y., Wang Z. ‘Get an early check—Chrysanthemum tea’: An outcome evaluation of a multimedia campaign promoting HIV testing among men who have sex with men in Hong Kong. HIV Med. 2018;19:347–354. doi: 10.1111/hiv.12583. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Zhong F., Tang W., Cheng W., Lin P., Wu Q., Cai Y., Tang S., Fan L., Zhao Y., Chen X., et al. Acceptability and feasibility of a social entrepreneurship testing model to promote HIV self-testing and linkage to care among men who have sex with men. HIV Med. 2017;18:376–382. doi: 10.1111/hiv.12437. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Noar S.M., Benac C.N., Harris M.S. Does tailoring matter? Meta-analytic review of tailored print health behavior change interventions. Psychol. Bull. 2007;133:673–693. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.133.4.673. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Lach H.W., Everard K.M., Highstein G., Brownson C.A. Application of the transtheoretical model to health education for older adults. Health Promot. Pract. 2004;5:88–93. doi: 10.1177/1524839903257305. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Paiva A.L., Lipschitz J.M., Fernandez A.C., Redding C.A., Prochaska J.O. Evaluation of the acceptability and feasibility of a computer-tailored intervention to increase human papillomavirus vaccination among young adult women. J. Am. Coll. Health. 2014;62:32–38. doi: 10.1080/07448481.2013.843534. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Bustamante M.J., A Konda K., Davey D.L.J., León S.R., Calvo G.M., Salvatierra J., Brown B., Caceres C.F., Klausner J.D. HIV self-testing in Peru: Questionable availability, high acceptability but potential low linkage to care among men who have sex with men and transgender women. Int. J. Std. AIDS. 2017;28:133–137. doi: 10.1177/0956462416630674. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

Data are contained within the article or supplementary materials.