Abstract

Around two percent of asymptomatic women in labor test positive for severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2) in Spain. Families and care providers face childbirth with uncertainty. We determined if SARS-CoV-2 infection at delivery among asymptomatic mothers had different obstetric outcomes compared to negative patients. This was a multicenter prospective study based on universal antenatal screening for SARS-CoV-2 infection. A total of 42 hospitals tested women admitted for delivery using polymerase chain reaction, from March to May 2020. We included positive mothers and a sample of negative mothers asymptomatic throughout the antenatal period, with 6-week postpartum follow-up. Association between SARS-CoV-2 and obstetric outcomes was evaluated by multivariate logistic regression analyses. In total, 174 asymptomatic SARS-CoV-2 positive pregnancies were compared with 430 asymptomatic negative pregnancies. No differences were observed between both groups in key maternal and neonatal outcomes at delivery and follow-up, with the exception of prelabor rupture of membranes at term (adjusted odds ratio 1.88, 95% confidence interval 1.13–3.11; p = 0.015). Asymptomatic SARS-CoV-2 positive mothers have higher odds of prelabor rupture of membranes at term, without an increase in perinatal complications, compared to negative mothers. Pregnant women testing positive for SARS-CoV-2 at admission for delivery should be reassured by their healthcare workers in the absence of symptoms.

Keywords: SARS-CoV-2, pregnancy, coronavirus, asymptomatic infection, perinatal outcomes, delivery, maternal complications

1. Introduction

To date, more than 11 million cases of the new severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2) and its disease COVID-19 have been confirmed worldwide, with more than half a million deaths [1]. Spain has been one of the most affected countries. Previous studies on viral respiratory infections have shown pregnant women to be at higher risk of obstetric and perinatal complications due to changes in their immune response [2]. Reports from the beginning of the pandemic suggest that pregnant women are at an increased risk of developing the more severe disease compared to the general population but also may suffer increased adverse perinatal outcomes [3]. Where systematic screening has been performed at admission for delivery, approximately 14% of women were found to be asymptomatic SARS-CoV-2-positive [4,5]. An increased rate of prelabor rupture of membranes in pregnancies of women with SARS-CoV-2 has previously been reported in a case series of symptomatic infections, including our population [6,7,8]. The obstetric outcome of asymptomatic infected pregnancies has not been well documented.

The Spanish Obstetric Emergency group urgently changed its objectives on 8 March 2020 to focus on documenting SARS-CoV-2 infection during pregnancy. Screening was commenced in all pregnant women admitted for delivery and continues to date across Spain. We found that around 2% of mothers, with no suspected infection or symptoms, test positive for SARS-CoV-2 [9]. These mothers, families, and care providers face childbirth with uncertainty on a daily basis. As information is lacking on perinatal characteristics and birth outcomes regarding asymptomatic SARS-CoV-2 infection at term, evidence-based counseling for mothers is limited. The objective of this study was to determine if SARS-CoV-2 infection before delivery among asymptomatic mothers, compared to SARS-CoV-2 negative asymptomatic pregnancies, had different obstetric outcomes.

2. Materials and Methods

This was a multicenter prospective study of consecutive cases of SARS-CoV-2 infection in a pregnancy cohort registered by the Spanish Obstetric Emergency group in 42 hospitals [9]. The registry’s objective updates were approved by the coordinating hospital’s Medical Ethics Committee on 23 March 2020 (reference number: PI 55/20); each collaborating center subsequently obtained protocol approval locally. The registry protocol is available at ClinicalTrials.gov, identifier NCT04558996. A complete list of authors and centers contributing to the study is provided as Supplementary Table S1. Upon recruitment, given the contagiousness of the disease and the lack of personal protection equipment, mothers consented by either signing a document, when possible, or verbally, which was recorded in the patient’s chart. A specific database was designed for recording information regarding SARS-CoV-2 infection in pregnancy. Data were entered by the lead researcher for each center after delivery, with a follow-up of six weeks postpartum in order to detect complications or symptomatic infections. We developed an analysis plan using the recommended contemporaneous methods and followed existing STROBE guidelines for reporting our results (Supplementary Table S2) [10].

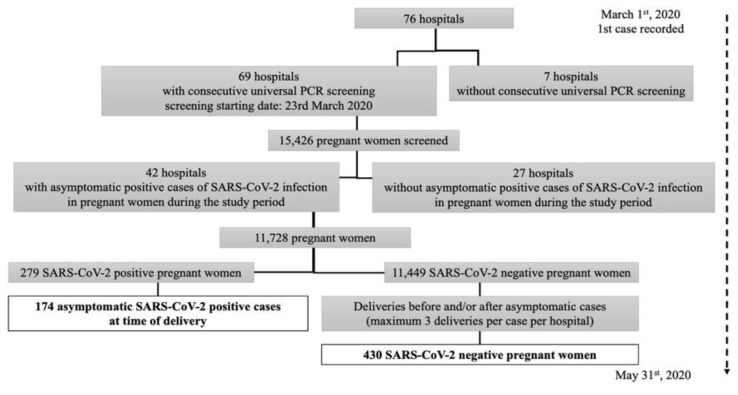

We included all asymptomatic obstetric patients, detected by screening for SARS-CoV-2 infection at admission to the delivery ward during the study period (23 March to 31 May 2020). We excluded women with symptoms during the antenatal period, at delivery, or during the postpartum six-week follow-up. SARS-CoV-2 infection was diagnosed by positive double-sampling polymerase chain reaction (PCR) from nasopharyngeal swabs. Noninfected patients were those defined as a negative PCR at admission to delivery, and with no symptoms pre- or post-partum. Each center provided between two and three PCR negative asymptomatic pregnancies per asymptomatic infected mother, by providing either a standardized randomization table or by selecting negative asymptomatic pregnancies that delivered immediately before and after each asymptomatic infected mother (Figure 1). This method was deployed to adjust for center conditions and management at the time of delivery and to decrease the risk of selection bias. Follow-up was performed up to six weeks postpartum for all patients to verify that symptoms did not develop and to ascertain birth outcomes.

Figure 1.

Flow chart of the study data. PCR, polymerase chain reaction; SARS-CoV-2, severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2.

Information regarding the demographic characteristics of each pregnant woman, comorbidities, and previous and current obstetric history was extracted from the clinical and verbal history of the patient. For perinatal events, we recorded gestational age (GA) at delivery, preterm delivery (below 37 weeks), stillbirth, the onset of labor, type of delivery, prelabor rupture of membranes (PROM), preterm prelabor rupture of membranes (PPROM), gestational hypertension, preeclampsia, obstetric hemorrhage, and thrombotic risk. Neonatal data included sex, birth weight, one- and five-minute Apgar scores, umbilical artery pH, and neonatal intensive care unit (NICU) admission. Definitions of clinical and obstetric conditions followed international criteria [11,12,13].

The studied variables were tested for normal distribution using Kolmogorov–Smirnov or Shapiro–Wilk tests. Descriptive data are presented as median (range), or percentage (number). p-values were obtained by Mann–Whitney’s U test for numerical variables and Pearson chi-squared or Fisher’s exact test for categorical variables. A p-value below 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

To compute the association of SARS-CoV-2 infection with obstetric outcomes of interest that were statistically significant in the univariate analysis, the potential influence of known and suspected measured confounding factors was controlled for with multivariable logistic regression modeling. We derived the adjusted odds ratios (aOR) with 95% confidence intervals (95% CI) after checking scientifically sound two-way interactions. The selection process for variables was driven by causal knowledge for the adjustment of confounders, verifying the statistical association of potential confounding factors with SARS-CoV-2 infection and the obstetric outcomes of interest (excluding intermediate variables of the causal chain), and it was based on previous findings and clinical constraints [11,12,13]. The complete list of covariates included in the maximum multivariable logistic regression model for the outcome of interest, after verifying the absence of significant interactions with SARS-CoV-2 infection, is as follows: multiple pregnancies, threatened abortion, ethnicity (categorized as Caucasian vs. non-Caucasian), smoking (categorized as current smokers/ex-smokers vs. non-smokers), chronic lung comorbidities (excluding asthma), and nulliparity, in accordance with the ten-to-one event per variable rule to avoid model overfitting [14]. Modeling was performed after excluding pregnancies with missing data; nulliparity had 1.4% missing values, whereas the other variables had none. A confounder remained in the model if the coefficient for SARS-CoV-2 infection changed by more than ten percent when the potential confounder was removed. Data were analyzed using the IBM SPSS Statistics 23 statistical package (Armonk, NY, USA: IBM Corp.); regression analyses were performed with the lme4 package in R, version 3·4 (RCore Team, 2017) [15].

3. Results

3.1. Main Results

3.1.1. General Date

During the study period, 11,728 patients were screened in 42 centers [9].

A total of 279 (2.4%) SARS-CoV-2 positive patients were identified, of which 174 patients were asymptomatic at pregnancy, admission, and during postpartum follow-up (62% of the infected population).

A total of 430 asymptomatic PCR negative patients were included.

3.1.2. Baseline Characteristics

No differences were found in anthropometric variables.

The asymptomatic infection group showed a significantly higher proportion of Latin American (p = 0·002) and Black ethnicities (p = 0·003) compared to the noninfected group.

Parity and blood type showed no SIGNIFICANT differences.

Maternal comorbidities evaluated were also similar between study groups (Table 1).

Obstetric history showed no differences between groups.

Table 1.

Baseline characteristics of the study participants (n = 604).

| Variable | Asymptomatic SARS-CoV-2 Positive Patients n = 174 |

SARS-CoV-2 Negative Patients n = 430 |

p-Value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Maternal characteristics | |||

| Maternal age (years) | 32.6 (18–45) | 33.2 (19–49) | NS |

| Maternal height (cm) | 163.3 (150–179) | 163.4 (150–180) | NS |

| Maternal weight (Kg) | 71.0 (42–123) | 70.6 (43–117) | NS |

| Maternal body mass index (Kg/m2) | 26·6 (16.0–48.1) | 26.5 (16·9–44.5) | NS |

| Obesity | 22 (12.6) | 63 (14.7) | NS |

| Ethnicity | |||

| Caucasian | 115 (66.1) | 348 (80.9) | <0.001 |

| Latin American | 34 (19.5) | 44 (10.2) | 0.002 |

| Black | 8 (4.6) | 3 (0.7) | 0.003 |

| Other | 17 (9.8) | 35 (8.2) | NS |

| Nulliparity | 65/171 (38.0) | 177/425 (41.6) | NS |

| A blood type | 67/153 (43.8) | 157/336 (46.7) | NS |

| Positive Rh status | 134/153 (87.6) | 300/336 (89.3) | NS |

| Maternal comorbidities | |||

| Chronic cardiac disease | 1 (0.6) | 3 (0.7) | NS |

| Chronic lung disease | 1 (0.6) | 1 (0.2) | NS |

| Asthma | 2 (1.1) | 12 (2.8) | NS |

| Thrombophilia | 2 (1.1) | 6 (1.4) | NS |

| Anemia | 5 (2.9) | 22 (5.1) | NS |

| Pregestational diabetes with insulin treatment | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | |

| Smoking | 21 (12.1) | 55 (12.8) | NS |

| Pregestational hypertension | 2 (1.1) | 2 (0.5) | NS |

| Obstetric history | |||

| Previous gestational hypertension | 5 (2.9) | 7 (1.6) | NS |

| Previous gestational thrombocytopenia | 3 (1.7) | 2 (0.5) | NS |

| Previous severe preeclampsia | 3 (1.7) | 2 (0.5) | NS |

| Previous growth restriction | 9 (5.2) | 14 (3.3) | NS |

Data shown as median(range), or n (percentage). p-values obtained by Mann–Whitney’s U test for numerical variables and Pearson chi-squared or Fisher’s exact test for categorical variables. SARS-CoV-2, severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2; NS, nonsignificant.

3.1.3. Pregnancy Characteristics

There were no significant differences between the proportions of singleton pregnancies, pregnancies by in vitro fertilization, those at high-risk for preeclampsia, thrombotic risk, or prophylactic treatment with either aspirin or heparin, the incidence of fetal anomalies, short cervix, vaccination, threatened preterm labor, or onset of labor.

In total, 62 (35.6%) asymptomatic patients were hospitalized antenatally, compared to 49 (11.4%) noninfected patients (p < 0.001).

Finally, there were no differences in the requirement of an intensive care unit for the mother, although one case from the asymptomatic group required intubation for noninfection-related complications (i.e., general anesthesia complications in a cesarean section due to placental abruption) (Table 2).

Table 2.

Pregnancy characteristics of the study participants (n = 604).

| Variable | Asymptomatic SARS-CoV-2 Positive Patients n = 174 |

SARS-CoV-2 Negative Patients n = 430 |

p-Value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Current pregnancy characteristics | |||

| Singleton pregnancy | 170 (97.7) | 418 (97.2) | NS |

| In vitro fertilization | 11 (6.3) | 14 (3.3) | NS |

| Threatened abortion | 9 (5.2) | 10 (2.3) | NS |

| High-risk for preeclampsia in 1rst trimester | 6 (3.4) | 24 (5.6) | NS |

| Aspirin prophylaxis | 14 (8.0) | 23 (5.3) | NS |

| Low-molecular weight heparin prophylaxis | 8 (4.6) | 11 (2.6) | NS |

| Fetal anomaly in first trimester | 1 (0.6) | 2 (0·5) | NS |

| Fetal anomaly in anatomy scan | 1 (0.6) | 8 (1.9) | NS |

| Group B Streptococcus infection | 25 (14.4) | 57 (13.3) | NS |

| Clinical and ultrasound prematurity screening | 3/162 (1.9) | 13/353 (3.7) | NS |

| Influenza vaccination | 85/156 (54.5) | 164/352 (46.6) | NS |

| Pertussis vaccination | 146/163 (89.6) | 342/377 (90.7) | NS |

| Threatened preterm labor | 4 (2.3) | 14/384 (3.6) | NS |

| Hospitalization before labor | 62 (35.6) | 49 (11.4) | <0·001 |

| Onset of labor | |||

| Elective caesarean section | 12 (6.9) | 19 (4.4) | NS |

| Spontaneous | 94 (54.0) | 264 (61.4) | |

| Induced | 68 (39.1) | 147 (34.2) | |

| Thrombotic risk | NS | ||

| Low | 143 (82.2) | 328 (76.3) | NS |

| Medium | 28 (16.1) | 85 (19.8) | NS |

| High | 3 (1.7) | 13 (30) | NS |

| Intensive care unit required | 1 (0.6) | 2 (0.5) | NS |

| Intubation required | 1 (0.6) | 0 (0.0) | NS |

Data shown as n (percentage). p-values obtained by Pearson chi-squared or Fisher’s exact test for categorical variables. SARS-CoV-2, severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2; NS, nonsignificant.

3.1.4. Obstetric Outcomes

No differences between GA at delivery, the incidence of preterm delivery (7.5% infected vs. 6.5% noninfected, OR = 1.16, 95% CI 0.59–2.29; not significant (NS)), cesarean section (20.7% infected vs. 17.2% noninfected, OR 1.25, 95% CI 0.81–1.95; NS) or stillbirth between groups.

OR of PROM at term (≥37 weeks of gestation) were notably higher in the infected group (17.8% infected vs. 10.2% noninfected, OR 1.90, 95% CI 1.16–3.13; p = 0.011), as well as when only nulliparous women were analyzed (26.2% infected vs. 11.9% noninfected, OR 2.63, 95% CI 1.29–5.36, p = 0.007).

Significant differences were found neither in the mode of delivery, gestational hypertension, preeclampsia, or obstetric hemorrhage, nor in PPROM (38.5% infected vs. 17.9% noninfected, OR 2.88, 95% CI 0.69–12.05; NS).

Finally, no maternal deaths were reported in both groups (Table 3).

Table 3.

Perinatal and neonatal data of the study population (n = 604).

| Variable | Asymptomatic SARS-CoV-2 Positive Patients n = 174 |

SARS-CoV-2 Negative Patients n = 430 |

p-Value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Perinatal data | |||

| Gestational age at delivery (weeks) | 39.0 (31–42) | 39.1 (28–42) | NS |

| Preterm delivery (below 37 weeks) | 7.5 (13) | 6.5 (28) | NS |

| Stillbirth | 1.1 (2) | 0.0 (0) | NS |

| PROM | 17.8 (31) | 10.2 (44) | 0.011 |

| PROM in nulliparous women | 26.2 (17/65) | 11.9 (21/177) | 0.007 |

| PPROM | 2.9 (5) | 1.2 (5) | NS |

| Onset of labor | |||

| Programmed caesarean section | 6.9 (12) | 4.4 (19) | NS |

| Spontaneous | 54.0 (94) | 61.4 (264) | |

| Induced | 39.1 (68) | 34.2 (147) | |

| Type of delivery | |||

| Caesarean | 20.7 (36) | 17.2 (74) | NS |

| Vaginal | 70.1 (122) | 67.2 (289) | |

| Vacuum or forceps | 9.2 (16) | 15.6 (67) | |

| Gestational hypertension | 6.4 (11) | 5.8 (24) | NS |

| Preeclampsia | |||

| Mild/moderate | 2.3 (4) | 4.9 (21) | NS |

| Severe | 1.7 (3) | 0.5 (2) | |

| Obstetric hemorrhage | 3.4 (6) | 4.7 (20) | NS |

| Thrombotic risk | |||

| Low | 82.2 (143) | 76.3 (328) | NS |

| Medium | 16.1 (28) | 19.8 (85) | |

| High | 1.7 (3) | 3.0 (13) | |

| Neonatal data | |||

| Male sex | 50.6 (86/170) | 48.2 (205/425) | NS |

| Birth weight (grams) | 3187 (315–4640) | 3249 (900–4610) | NS |

| 1’ Apgar score | 9 (0–10) | 9 (1–10) | NS |

| 5’ Apgar score | 10 (0–10) | 10 (5–10)1 | NS |

| Umbilical artery pH | 7.26 (7.04–7.42) | 7.26(6.90–7.46) | NS |

| NICU admission | 6.9 (12) | 1.6 (7) | 0.001 |

| Days in NICU | 13.2 (1–48) | 11.2 (5–17) | NS |

| Cause of NICU admission: | NS | ||

| Prematurity | 25 (3/12) | 71.4 (5/7) | NS |

| Respiratory distress | 16.7 (2/12) | 14.3 (1/7) | NS |

| COVID-19 protocol | 33.3 (4/12) | 0.0 (0/7) | NS |

Data are shown as mean/range, or percentage(n). p-values obtained by Mann–Whitney’s U test for continuous variables and Pearson chi-squared or Fisher’s exact test for categorical variables. SARS-CoV-2, severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2; NS, nonsignificant; PROM, Premature rupture of membranes; PPROM, Preterm premature rupture of membranes; NICU, neonatal intensive care unit.

3.1.5. Neonatal Data

Neonatal variables also showed no differences in sex, birth weight, Apgar scores, or umbilical artery pH

There was a significant difference between admission to the NICU between groups (6.9% infected vs. 1.6% noninfected, OR 4.48, 95% CI 1.73–11.55; p = 0.001), although the length of hospitalization was similar (median 13.2 days infected vs. 11.2 days noninfected; NS) (Table 3).

3.1.6. Multivariable Logistic Model

The final estimated multivariable logistic model, after excluding eight pregnancies with missing data, confirmed the association of SARS-CoV-2 infection with PROM among term pregnancies. An 88% increase in PROM occurred in the asymptomatic SARS-CoV-2 positive group compared to the negative group (aOR 1.88, 95% CI 1.13–3.11; p = 0.015), with no other covariate selected by the model (Table S3).

4. Discussion

To our knowledge, based on a thorough inspection of the obstetric COVID-19 literature, this is the first study to compare totally asymptomatic SARS-CoV-2 positive mothers with those not infected at delivery. Our results show a significant difference in the odds of PROM among pregnancies at term in a multivariate model, a feature not previously described.

Approximately 60% of SARS-CoV-2 positive patients identified at delivery were asymptomatic, which agrees with previously published data in our setting [4]. Baseline characteristics of our participants show a higher proportion of Latin American and Black ethnicity in the asymptomatic infected patients, which is consistent with previous literature suggesting a higher risk of infection, and, therefore, obstetric findings were adjusted for this characteristic. This higher risk of infection may be explained by socioeconomic factors, such as the type of work performed, family cohabitation, and comorbidities associated with ethnicity [16]. We found no differences in blood group type, comorbidities, or obstetric history, which have been reported as associated with progression and aggression of the infection [17,18].

Hospitalization before delivery was higher in infected mothers, a feature that is likely to be associated with the diagnosis of SARS-CoV-2 infection; in the early stages of the pandemic, many centers were not prepared to discharge a woman home upon confirming a SARS-CoV-2 infection. Many of these patients stayed for observation and isolation, with an average hospitalization stay of one day. On the other hand, maternal intensive care unit requirements were not different between groups, and less than those reported for symptomatic infections, as expected [19].

Our main finding is a higher proportion of PROM among term pregnancies (beyond 37 weeks of gestation) in the asymptomatic cohort when compared to noninfected women. This proportion was particularly important in the group of nulliparous women, which have no previous pregnancy risk factors that may increase PROM, such as cesarean section, previous preterm delivery, or adverse perinatal outcomes such as preeclampsia. The association of asymptomatic infection by SARS-CoV-2 with PROM has not been previously reported, mainly because at the beginning of the pandemic, universal screening was not performed upon admission to delivery wards, and secondly, because there are no previous reports comparing asymptomatic infected and noninfected patients. A previous screening study showed that approximately 14% of women were asymptomatic SARS-CoV-2-positive patients when admitted for delivery [5]; this has been recently confirmed by antibody testing from maternal serum in the first and third trimesters of pregnancy in our setting [4], which suggests that initial studies reporting on SARS-CoV-2 infection in pregnant women probably presented a selection bias regarding the presence of symptoms.

Asymptomatic infection of SARS-CoV-2 may be associated with abnormal imaging, with studies suggesting subclinical repercussion and altered immunity [20]. There are reports suggesting that a considerable number of asymptomatic patients may have lung opacities on computer tomography, with ground-glass opacities and consolidation [21]. Other findings reported in asymptomatic infections are lymphopenia, thrombocytopenia, elevated liver enzymes, and a decreased immune response [20]. Subclinical infections in pregnancy may be associated with PROM by various mechanisms, such as activation of inflammation. However, this has usually been associated with symptomatic infections [22].

Our findings support the hypothesis that a subclinical SARS-CoV-2 infection in pregnancy may result in PROM. However, it does not appear to be associated with increased preterm delivery or neonatal risks, probably because the asymptomatic status indicates a lower level of infective ailment. In the case of PPROM, the observed odds were consistent with PROM results, but potentially due to a lack of power, the possible association of SARS-CoV-2 infection with this outcome could not be confirmed. Perinatal outcomes were similar between our groups and more favorable than those reported in symptomatic patients, with lower rates of caesarean section, prematurity, thrombotic disease, preeclampsia, and growth restriction [3,19]. This leads us to believe that many obstetric outcomes may be related to maternal symptom severity. In the absence of symptoms, mothers can be reassured about perinatal outcomes. Likewise, the observed high NICU admission rate may be influenced by the presence of the infection, as many neonates may have been admitted for observation due to the maternal diagnosis. There have recently been arguments for and against universal screening in labor wards because of stigmatization and risk of separation of the mother and neonate [23]. We believe that our results from asymptomatic patients favor universal screening for protection of healthcare workers, warning clinicians that further protective measures should be undertaken, but symptoms and maternal clinical severity may be the determinant factors with regard to the management of the neonate and the possibility of direct breastfeeding without mother–baby separation, with adequate hygienic measures [24,25].

Our study has various strengths: in particular, a prospective screening program with a well-designed database which allowed us to record many characteristics of this novel infection. We evaluated outcomes during the antenatal period, at delivery, and during the postpartum six-week follow-up, in a uniform way for both the infected cohort and the uninfected comparison group. The SARS-CoV-2 negative comparison group was selected from the same centers where the infected mothers delivered and within the same timeframe so as to have similar conditions, thereby minimizing selection and performance biases. Both groups were well defined: more than one-third of the SARS-CoV-2 positive patients were antenatally admitted for observation, and every study participant follow-up was completed 6-week postpartum, allowing us to exclude mothers who became symptomatic after birth. We are therefore confident about establishing the asymptomatic status of mothers in the study. Multivariable analyses allowed for control of confounding variables included in the model. We acknowledge as a limitation the absence of the complete screened cohort; thus, our study has a hybrid design comprised of a prospective cohort of cases, with controls delivered immediately before and after each asymptomatic infected mother, representative of our population. The PCR negative comparison group was a subsample of the screen-negative cohort from all 42 hospitals that had PCR positive asymptomatic mothers. However, the concurrent method applied for the selection of a noninfected cohort allowed for a comparison unaffected by the difference in time of exposure and outcome assessment. We believe our findings are trustworthy, and the multicenter nature of the study adds to its generalizability.

5. Conclusions

Totally asymptomatic women with SARS-CoV-2 infection in pregnancy had higher PROM among term pregnancies compared to noninfected patients. Neonates had higher NICU admission rates, likely due to the isolation and observation protocols associated with maternal PCR positive status. We believe screening for SARS-CoV-2 infection in pregnant patients at admission to delivery may be necessary for the protection of healthcare workers. However, the presence of symptoms and maternal clinical severity appear to be the most relevant factors to determine mother–baby separation and direct breastfeeding, with adequate hygiene measures. Therefore, pregnant women who are SARS-CoV-2 positive at admission to the delivery ward should be reassured by their healthcare workers in the absence of symptoms, as low risk of infection-related obstetric morbidity and adverse outcomes are observed.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank José Montes (Effice Research) for his support in organizing and cleansing the database, Juan Antonio De León Luis (Gregorio Marañon University Hospital) for his critical revision and comments on the manuscript, and Khalid Saeed Khan (University of Granada) and Ana Royuela (IDIPHISA Biomedical Research Institute; CIBERESP) for their scientific advice. We would like to thank the principal investigators of the following centers for their collaboration in the OBS COVID Registry: Hospital Universitario Virgen de la Arrixaca—Murcia, Hospital Costa del Sol, Complejo Hospitalario San Millán—San Pedro de la Rioja, Complejo Hospitalario Universitario de Ourense, Complejo Hospitalario de Santiago de Compostela, Hospital Universitario Los Arcos del Mar Menor, Hospital Lucus Augusti, Hospital Rafael Méndez, Hospital Universitario de Fuenlabrada, Hospital General La Mancha Centro, Complejo Hospitalario Universitario de Pontevedra, Hospital Universitario de Ferrol, Hospital Alvaro Cunqueiro, Hospital Universitario Reina Sofía Hospital Universitario Puerta del Mar. Cádiz, Hospital General Universitario Santa Lucía de Cartagena, Hospital Universitario Torrecardenas, Hospital Virgen del Rocío, Complejo Hospitalario Jaen, Hospital da Barbanza, AGSE Hospital Axarquia, Hospital Santa Ana. Motril, Hospital Universitario de Basurto Bilbao, Hospital Quironsalud Marbella, Hospital Universitario de Ceuta, Hospital Universitario Parc Taulí de Sabadell, Hospital Infanta Margarita de Cabra, Hospital de Montilla y Quironsalud Cordoba, Hospital La Linea, Complejo Asistencial Universitario de Salamanca, Hospital Alto Guadalquivir, Andújar, Hospital General de L’Hospitalet, Hospital Regional de Málaga, Hospital Quironsalud Málaga, and Hospital de Minas de Riotinto Huelva.

Supplementary Materials

The following are available online at https://www.mdpi.com/1999-4915/13/1/112/s1, Table S1: List of authors and hospital members of the Spanish Obstetric Emergency Group included in this study (n = 42), Table S2: STROBE Statement—a checklist of items that should be included in reports of observational studies, Table S3: Odds ratio (OR) and adjusted odds ratio (aOR) with the corresponding 95% confidence intervals and p-values for the outcomes associated with SARS-CoV-2 infection in pregnancy.

Author Contributions

M.C.-L. and E.F.P. contributed to the conception and design of the study, acquisition of data, analysis, and interpretation of data, and drafted the manuscript and revised it critically. M.L.d.l.C.C. contributed to the design and analysis of data, manuscript drafting, and critical revision. A.C.A. centralized and cleansed the screening data. M.B.E.P., P.P.R. (Pilar Prats Rodríguez), M.M.H., L.F.A., P.P.R. (Pilar Pintado Recarte), M.d.C.M.M., N.P.P., J.C.R., A.V.Y., O.N.V., P.G.d.B.F., C.M.O.L., B.M.P., B.M.A., L.F.R., A.R.V., M.J.J.F., M.A.A.-M., C.C.P., O.A.M., C.L.H., J.C.W.d.A., A.P.S.J., M.M.B., C.A.C., A.S.M., L.P.A., R.A.S., M.L.R., M.C.B.L., M.R.M.C., O.V.R., E.M.A., M.J.N.V., C.F.F., A.T.N., A.M.C.G., S.S.P., I.G.A., J.A.G., A.P.P., R.O.S., M.d.P.G.M., M.C.C., S.E.M., and J.A.S.B. collected and curated the data and critically revised the manuscript; M.R.G.E. critically revised the manuscript and was responsible for the bibliography search and citations; S.C.M. critically revised the manuscript and aided in revising the English language; O.M.P. contributed to the coordination of the registry, conception and design of the study, data collection for its analysis, interpretation of results, and drafting of the article and revising it critically. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This project was supported by public funds obtained in competitive calls: Grant COV20/00021 (EUR 43,000 from the Instituto de Salud Carlos III—Spanish Ministry of Health and co-financed with Fondo Europeo de Desarrollo Regional (FEDER) funds. Dr Cruz-Lemini is supported by a Juan Rodés contract JR19/00047, Instituto de Salud Carlos III—Spanish Ministry of Health. The funding bodies had no role in the study design, in the collection or analysis of the data, or in manuscript writing.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted according to the guidelines of the Declaration of Helsinki and approved by the Institutional Review Board (or Ethics Committee) of Puerta del Hierro Hospital (PE 55/20, 23 March 2020).

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this study are available on request from the corresponding author. The data are not publicly available due to the multicenter nature of the study.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Footnotes

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.WHO Naming the Coronavirus Disease (COVID-19) and the Virus that Causes it. [(accessed on 13 December 2020)];2020 Available online: https://www.who.int/emergencies/diseases/novel-coronavirus-2019/technical-guidance/naming-the-coronavirus-disease-(covid-2019)-and-the-virus-that-causes-it.

- 2.Wong S.F., Chow K.M., Leung T.N., Ng W.F., Ng T.K., Shek C.C., Ng P.C., Lam P.W., Ho L.C., To W.W., et al. Pregnancy and perinatal outcomes of women with severe acute respiratory syndrome. Am. J. Obstet. Gynecol. 2004;191:292–297. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2003.11.019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Juan J., Gil M.M., Rong Z., Zhang Y., Yang H., Poon L.C. Effect of coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) on maternal, perinatal and neonatal outcome: Systematic review. Ultrasound Obstet. Gynecol. 2020;56:15–27. doi: 10.1002/uog.22088. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Crovetto F., Crispi F., Llurba E., Figueras F., Gomez-Roig M.D., Gratacos E. Seroprevalence and presentation of SARS-CoV-2 in pregnancy. Lancet. 2020;396:530–531. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(20)31714-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Sutton D., Fuchs K., D’Alton M., Goffman D. Universal Screening for SARS-CoV-2 in Women Admitted for Delivery. N. Engl. J. Med. 2020;382:2163–2164. doi: 10.1056/NEJMc2009316. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Chen H., Guo J., Wang C., Luo F., Yu X., Zhang W., Li J., Zhao D., Xu D., Gong Q., et al. Clinical characteristics and intrauterine vertical transmission potential of COVID-19 infection in nine pregnant women: A retrospective review of medical records. Lancet. 2020;395:809–815. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(20)30360-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Li N., Han L., Peng M., Lv Y., Ouyang Y., Liu K., Yue L., Li Q., Sun G., Chen L., et al. Maternal and neonatal outcomes of pregnant women with COVID-19 pneumonia: A case-control study. Clin. Infect. Dis. 2020;71:2035–2041. doi: 10.1093/cid/ciaa352. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Yang H., Hu B., Zhan S., Yang L.Y., Xiong G. Effects of Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome Coronavirus 2 Infection on Pregnant Women and Their Infants. Arch. Pathol. Lab. Med. 2020;144:1217–1222. doi: 10.5858/arpa.2020-0232-SA. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Encinas Pardilla M.B., Caño Aguilar Á., Marcos Puig B., Sanz Lorenzana A., Rodríguez de la Torre I., Hernando López de la Manzanara P., Fernández Bernardo A., Martínez Pérez Ó. Spanish registry of Covid-19 screening in asymptomatic pregnants. Rev. Esp. Salud. Publica. 2020;18:e202009092. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Von Elm E., Altman D.G., Egger M., Pocock S.J., Gotzsche P.C., Vandenbroucke J.P., Initiative S. The Strengthening the Reporting of Observational Studies in Epidemiology (STROBE) Statement: Guidelines for reporting observational studies. Int. J. Surg. 2014;12:1495–1499. doi: 10.1016/j.ijsu.2014.07.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists, Committee on Practice B-O. Prelabor Rupture of Membranes: ACOG Practice Bulletin, Number 217. Obstet. Gynecol. 2020;135:e80–e97. doi: 10.1097/AOG.0000000000003700. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Brown M.A., Magee L.A., Kenny L.C., Karumanchi S.A., McCarthy F.P., Saito S., Hall D.R., Warren C.E., Adoyi G., Ishaku S., et al. Hypertensive Disorders of Pregnancy: ISSHP Classification, Diagnosis, and Management Recommendations for International Practice. Hypertension. 2018;72:24–43. doi: 10.1161/HYPERTENSIONAHA.117.10803. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Thomson A.J., Royal College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists Care of Women Presenting with Suspected Preterm Prelabour Rupture of Membranes from 24(+0) Weeks of Gestation: Green-top Guideline No. 73. BJOG. 2019;126:e152–e166. doi: 10.1111/1471-0528.15803. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Peduzzi P., Concato J., Kemper E., Holford T.R., Feinstein A.R. A simulation study of the number of events per variable in logistic regression analysis. J. Clin. Epidemiol. 1996;49:1373–1379. doi: 10.1016/S0895-4356(96)00236-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Bates D., Mächler M., Bolker B., Walker S. Fitting Linear Mixed-Effects Models Using lme4. arXiv. 20151406.5823 [Google Scholar]

- 16.Pan D., Sze S., Minhas J.S., Bangash M.N., Pareek N., Divall P., Williams C.M., Oggioni M.R., Squire I.B., Nellums L.B., et al. The impact of ethnicity on clinical outcomes in COVID-19: A systematic review. E Clin. Med. 2020;23:100404. doi: 10.1016/j.eclinm.2020.100404. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Chen N., Zhou M., Dong X., Qu J., Gong F., Han Y., Qiu Y., Wang J., Liu Y., Wei Y., et al. Epidemiological and clinical characteristics of 99 cases of 2019 novel coronavirus pneumonia in Wuhan, China: A descriptive study. Lancet. 2020;395:507–513. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(20)30211-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Li J., Wang X., Chen J., Cai Y., Deng A., Yang M. Association between ABO blood groups and risk of SARS-CoV-2 pneumonia. Br. J. Haematol. 2020;190:24–27. doi: 10.1111/bjh.16797. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Breslin N., Baptiste C., Gyamfi-Bannerman C., Miller R., Martinez R., Bernstein K., Ring L., Landau R., Purisch S., Friedman A.M., et al. Coronavirus disease 2019 infection among asymptomatic and symptomatic pregnant women: Two weeks of confirmed presentations to an affiliated pair of New York City hospitals. Am. J. Obstet. Gynecol. MFM. 2020;2:100118. doi: 10.1016/j.ajogmf.2020.100118. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Long Q.X., Tang X.J., Shi Q.L., Li Q., Deng H.J., Yuan J., Hu J.L., Xu W., Zhang Y., Lv F.J., et al. Clinical and immunological assessment of asymptomatic SARS-CoV-2 infections. Nat. Med. 2020;26:1200–1204. doi: 10.1038/s41591-020-0965-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Cella L., Gagliardi G., Hedman M., Palma G. Injuries from Asymptomatic COVID-19 Disease: New Hidden Toxicity Risk Factors in Thoracic Radiation Therapy. Int. J. Radiat. Oncol. Biol. Phys. 2020;108:394–396. doi: 10.1016/j.ijrobp.2020.06.055. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Goldenberg R.L., Culhane J.F., Iams J.D., Romero R. Epidemiology and causes of preterm birth. Lancet. 2008;371:75–84. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(08)60074-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Metz T.D. Is Universal Testing for Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome Coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2) Needed on All Labor and Delivery Units? Obstet. Gynecol. 2020;136:227–228. doi: 10.1097/AOG.0000000000003972. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Cheema R., Partridge E., Kair L.R., Kuhn-Riordon K.M., Silva A.I., Bettinelli M.E., Chantry C.J., Underwood M.A., Lakshminrusimha S., Blumberg D. Protecting Breastfeeding during the COVID-19 Pandemic. Am. J. Perinatol. 2020 doi: 10.1055/s-0040-1714277. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Palatnik A., McIntosh J.J. Protecting Labor and Delivery Personnel from COVID-19 during the Second Stage of Labor. Am. J. Perinatol. 2020;37:854–856. doi: 10.1055/s-0040-1709689. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this study are available on request from the corresponding author. The data are not publicly available due to the multicenter nature of the study.