Abstract

Purpose

To describe first clinical experience with a directly image-able, inherently radio-opaque microspherical embolic agent for transarterial embolization of liver tumors.

Methodology

LC Bead LUMI™ is a new product based upon sulfonate-modified polyvinyl alcohol hydrogel microbeads with covalently bound iodine (∼260 mg I/ml). 70–150 μ LC Bead LUMI™ iodinated microbeads were injected selectively via a 2.8 Fr microcatheter to near complete flow stasis into hepatic arteries in three patients with hepatocellular carcinoma, carcinoid, or neuroendocrine tumor. A custom imaging platform tuned for LC LUMI™ microbead conspicuity using a cone beam CT (CBCT)/angiographic C-arm system (Allura Clarity FD20, Philips) was used along with CBCT embolization treatment planning software (EmboGuide, Philips).

Results

LC Bead LUMI™ image-able microbeads were easily delivered and monitored during the procedure using fluoroscopy, single-shot radiography (SSD), digital subtraction angiography (DSA), dual-phase enhanced and unenhanced CBCT, and unenhanced conventional CT obtained 48 h after the procedure. Intra-procedural imaging demonstrated tumor at risk for potential under-treatment, defined as paucity of image-able microbeads within a portion of the tumor which was confirmed at 48 h CT imaging. Fusion of pre- and post-embolization CBCT identified vessels without beads that corresponded to enhancing tumor tissue in the same location on follow-up imaging (48 h post).

Conclusion

LC Bead LUMI™ image-able microbeads provide real-time feedback and geographic localization of treatment in real time during treatment. The distribution and density of image-able beads within a tumor need further evaluation as an additional endpoint for embolization.

Keywords: Hepatic, Embolization, Image-able

Introduction

Intra-procedural CBCT obtained immediately post-embolization showed correspondence in microbead distribution with conventional CT obtained 48 h later. In addition to the traditional endpoint metric of flow stasis, the distribution and density of image-able beads within a tumor need further evaluation as an additional endpoint for embolization.

Technical Note

Three patients with liver neoplasms were treated via the hepatic arteries with directly image-able iodinated embolization microbeads, as part of an IRB-approved clinical trial to evaluate the image-ability of LC Bead LUMI™ during embolization of liver tumors. Tumor histologies included hepatocellular carcinoma, metastatic carcinoid, and metastatic neuroendocrine. Written informed consent was obtained from all individual participants included in the study. All procedures were performed under general anesthesia. All procedures performed in studies involving human participants were in accordance with the ethical standards of the institutional and/or national research committee and with the 1964 Helsinki declaration and its later amendments or comparable ethical standards.

Patient #1 An 86-year-old male presented with familial mid gut carcinoid stage IV in June, 2012, and underwent surgical resection with liver wedge resections in segments II, VII, and VIII, and ablation of a lesion in segment III for metastatic carcinoid disease. He progressed 2 years later with multiple skeletal and liver lesions, as well as scattered increased Octreoscan uptake in the mesentery and retroperitoneum. Everolimus was ineffective at halting progression. The patient then underwent sequential bland hepatic transarterial embolization (TAE) of right hepatic segments VI and VII in July, 2015 with one syringe of 100 μ microspheres (Embozene, CeloNova) followed in November, 2015 with two syringes of 100 μ microspheres and 0.3 syringe of 400 μ microspheres to left lobe segments II, III, and IV. Sandostatin dosage required to control neuroendocrine symptoms had slowly increased over the months prior to embolization.

In January, 2016, his third superselective TAE session of segments V and VIII was performed with 1 ml (sedimented bead volume) of 70–150 μ LC Bead LUMI™ radiopaque microbeads (Biocompatibles, UK Ltd, a BTG International group company), diluted 10:1 in Omnipaque 350 contrast. Target vessels were selected using dedicated embolization planning and guidance software (EmboGuide, Philips), including dual-phase CBCT, semi-automatic segmentation of tumors and target volumes, automatic feeding vessel detection, and 3D road mapping of the vessels and target volume. The target volume was selected with a segmentation tool by outlining a relatively hypervascular volume of the right lobe containing numerous coalescing rim-enhancing tumors. TAE with 70–150 μ LC Bead LUMI™ was performed until 3 heartbeat stasis was reached. CBCT protocols optimized for LC Bead LUMI™ visualization were utilized immediately and 10-min post microbead embolization (Figs. 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6).

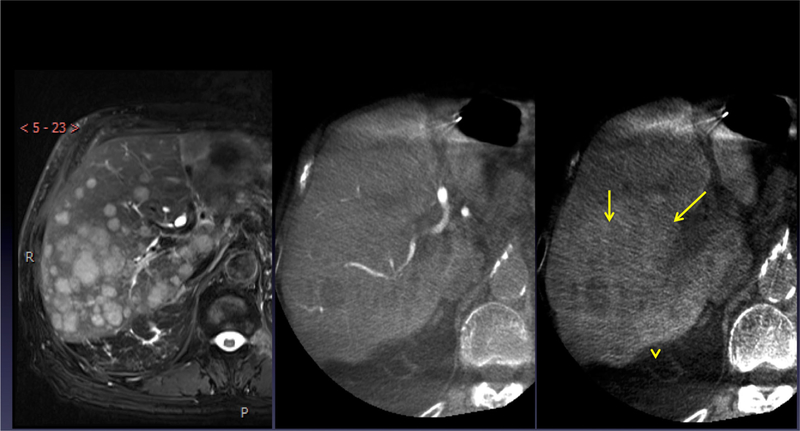

Fig. 1.

Patient 1: T2-weighted fat saturation MRI image (left) showing multiple hepatic metastases. Dual-phase CBCT, arterial phase (middle), and parenchymal phase (right), showing arterial anatomy and large confluent masses (yellow arrows) in segments VI and VII

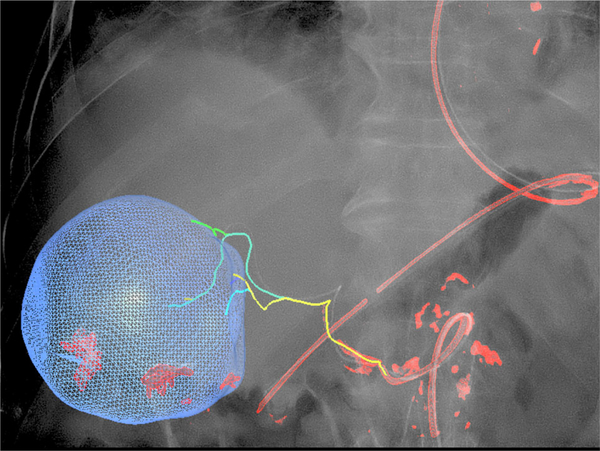

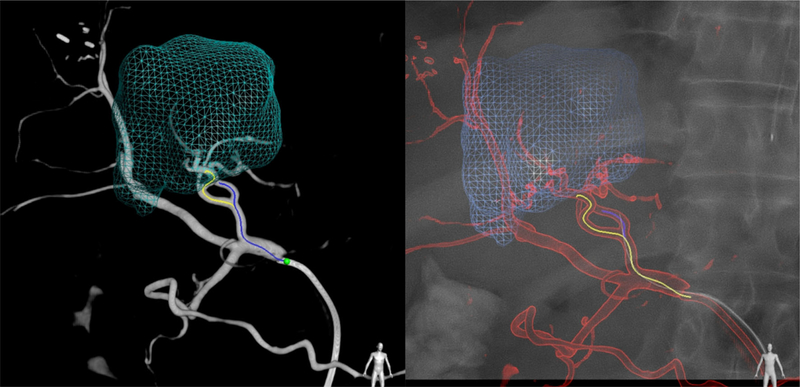

Fig. 2.

Patient 1: 3D dynamic roadmap displayed on fluoroscopy after dual-phase CBCT, target volume segmentation, automatic feeding vessel detection, and selective microcatheterization

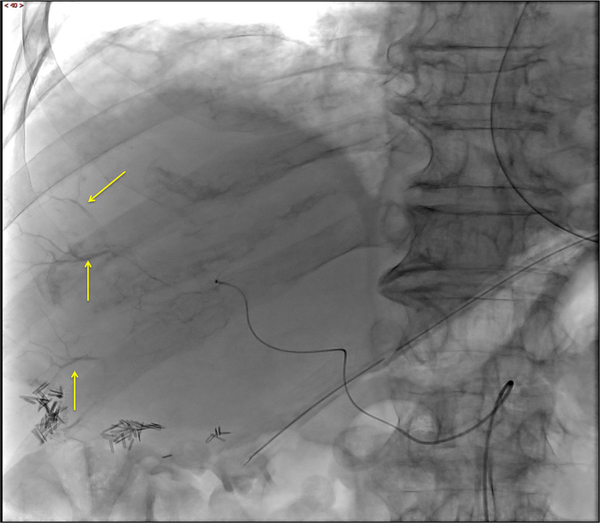

Fig. 3.

Patient 1: SSD showing retained LUMI™ microbeads (yellow arrows)

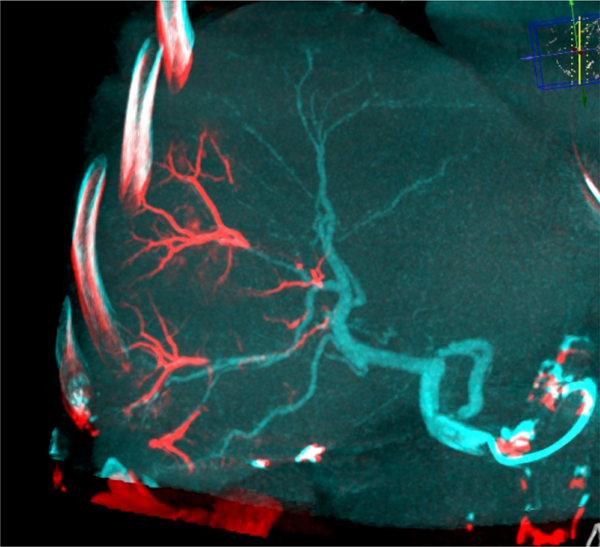

Fig. 4.

Patient 1: dual-view fusion of final CBCT with beads (red) overlaid on arterial non-selective CBCT (blue) clearly identifies the vascular regions targeted by the LC Bead LUMI™ injections

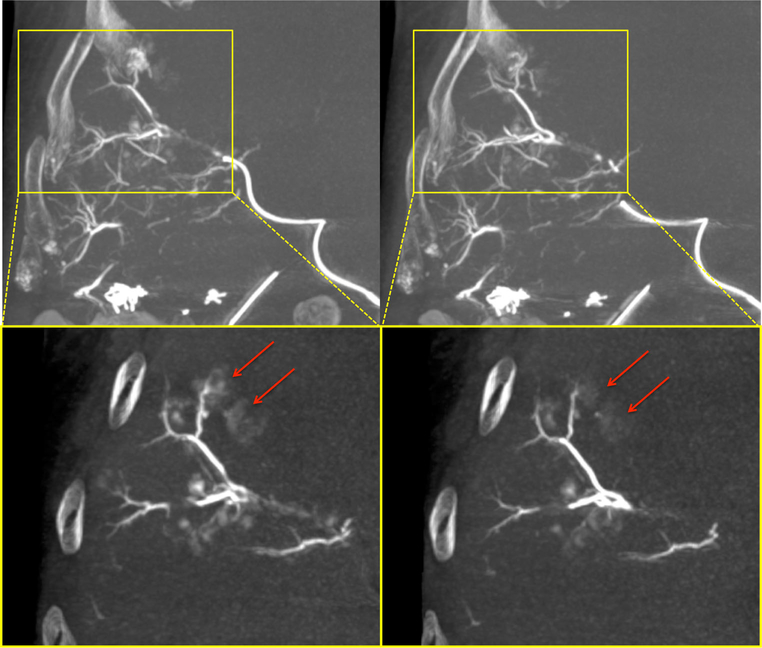

Fig. 5.

Patient 1: final post-embolization MIP CBCTs acquired just after the completion of embolization (left) and then 10 min later (right). In the yellow, zoomed, thin MIP slabs, the less dense perivascular blush of contrast (red arrows) washes out over time, while the higher density vessels filled with microbeads remain unchanged

Fig. 6.

Patient 1: 10-min post-embolization CBCT (left) shows perivascular cloud-like contrast which continues to clear or wash out by the 48 h standard unenhanced CT (right). Some of this difference is also accounted for by the higher spatial resolution and iodine detection sensitivity of CBCT versus standard CT

Patient #2 A 61-year-old male with an intermediate grade ileal neuroendocrine tumor metastatic to umbilicus and liver underwent surgical resection of the primary and of a liver metastasis in July 2015. He remained asymptomatic but presented with a 5.5 cm dominant liver mass in segment IV, and multiple scattered liver lesions under 2 cm. Feeding vessels were identified using dual-phase CBCT and EmboGuide navigation software, and 3D roadmap helped navigate selective embolization with 1.2 ml of 70–150 μ LC Bead LUMI™. After 3 heart beat stasis was achieved, fusion of arterial phase non-selective pre-embolization CBCT and post-embolization unenhanced CBCT was performed to identify tumor vessels without beads, or vessels that may have not have received enough beads to opacify above a threshold. The registration and fusions were performed using the Dual-View "overlay" function, which revealed a single anterior third-order left hepatic artery branch along the right anterolateral margin of the segment IV tumor which was not visibly filled with opaque beads, despite a proximal catheter position, potentially identifying tissue at risk for under-treatment. This artery was patent on the initial enhanced CBCT but did not fill with image-able microbeads on post-embolization non-enhanced CBCT. Colorized CBCT fusion image demonstrated that this vessel resides in the location of enhancing tumor seen on 48 h CT scan in the same region (Figs. 7, 8, 9, 10, 11, 12).

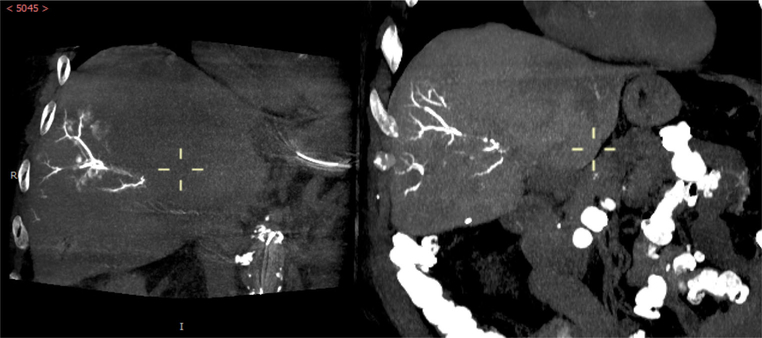

Fig. 7.

Patient 2: dominant segment IV lesion (yellow arrow) identified on axial contrast-enhanced MRI (left), late arterial phase conventional CT (middle), and common hepatic artery DSA prior to embolization (right)

Fig. 8.

Patient 2: pre-embolization arterial phase (left) and parenchymal phase (right) dual-phase CBCT showing target lesion in segment IV (yellow arrows)

Fig. 9.

Patient 2: emboguide image showing segmented target tumor and feeding vessels (left) and feeding arteries superimposed on live fluoroscopic image during selective catheterization (right)

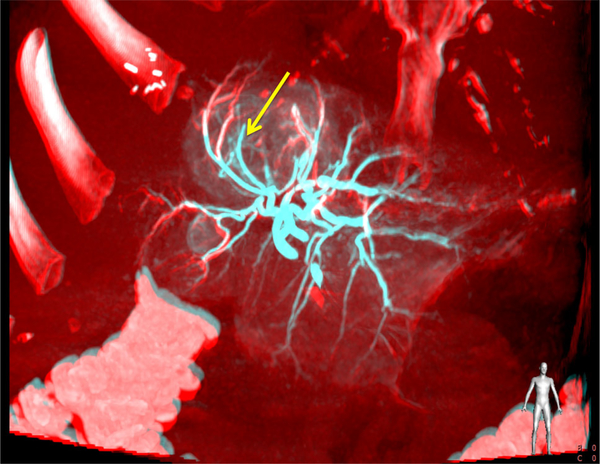

Fig. 10.

Patient 2: dual-view image of fused pre-embolization CBCT with intra-arterial contrast and post-embolization CBCT. Blue color indicates patent vessels prior to embolization, while red overlay documents the presence of LC LUMI™ microbeads. Yellow arrow points to tumor vessel which has failed to accumulate embolization microbeads

Fig. 11.

Patient 2: dual-view fused MIP demonstrating the tumor vessel without LC LUMI™ microbeads (yellow arrow) identified in Fig. 10

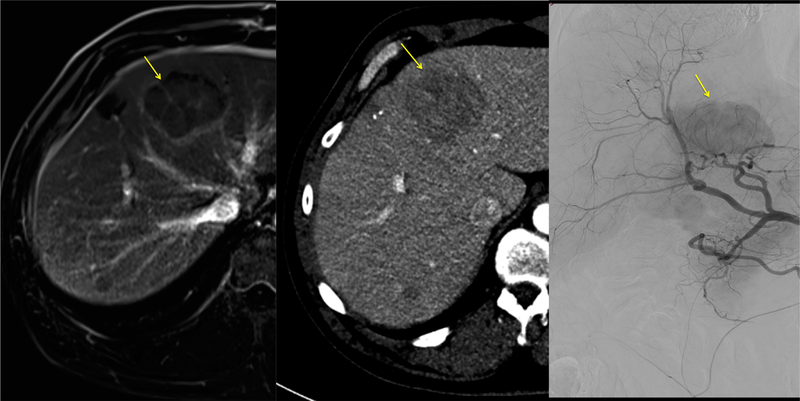

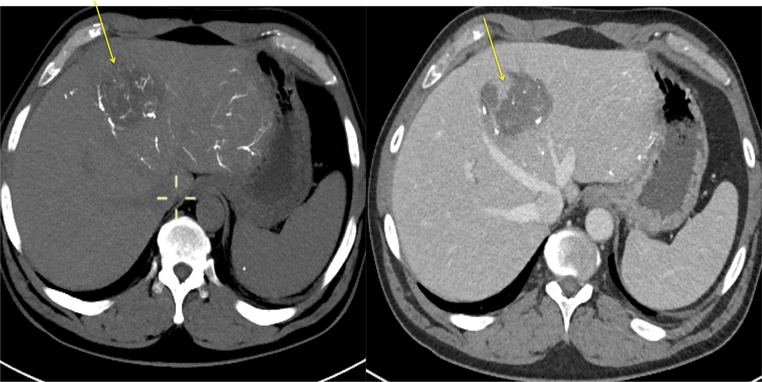

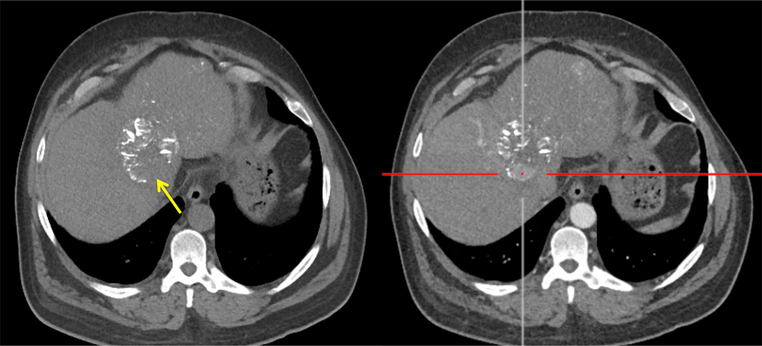

Fig. 12.

Patient 2: pre- and post-contrast CT obtained 48 h after LC LUMI™ embolization reveals a tumor zone with a paucity of microspheres (left, yellow arrow) and corresponding persistent perfused, viable tumor (right, yellow arrow). This viable tumor corresponds to the tumor vessel in Fig. 10 which failed to accumulate microbeads

Patient #3 A 63-year-old male with hepatitis C and an AFP of 3236 was diagnosed by MRI and biopsy in May and June 2015, respectively, with a multi-focal well-differentiated hepatocellular carcinoma (Edmondson Grade 2) with a dominant segment IV liver mass measuring 8 × 7.1 cm. He underwent pre-treatment with Tremelimumab anti-CTLA4 checkpoint inhibitor immunotherapy and selective embolization of the left hepatic artery with doxorubicin-loaded 100–300 μ LC beads after immunomodulation therapy. LC Bead LUMI™ and navigation software were used in his second embolization session. Following segmentation, feeding vessel identification, and three-dimensional CBCT roadmapping, 2 out of 3 feeding vessels were selectively injected with doxorubicin-loaded 100–300 μ bead and LC Bead LUMI™ sequentially, in alternating 1–3 ml aliquots of each bead type, until 3 heart beat stasis was achieved in each feeding vessel. Selective embolization of the left hepatic artery branch from the left gastric-left hepatic trunk and left hepatic artery was performed with alternating aliquots of 1–3 ml suspension (70–150 μ LC Bead LUMI™ alternating with 100–300 μ bead loaded with doxorubicin). A total of 4 ml packed volume of 70–150 μ LC Bead LUMI™ and 3.2 ml of bead containing 80 mg doxorubicin were administered in a 1:10 dilution in Omnipaque 350. CBCT demonstrated accumulation of density corresponding to microbead suspension both within and at the periphery of the embolized tumor (Fig. 15). Dual-view CBCT fusion of pre- to post-embolization with LC Bead LUMI™ identified a small region of the dominant tumor likely supplied by the right hepatic artery. Additional therapy was delayed secondary to the total fluoroscopy time and cumulative contrast dose (Figs. 13, 14, 15, 16).

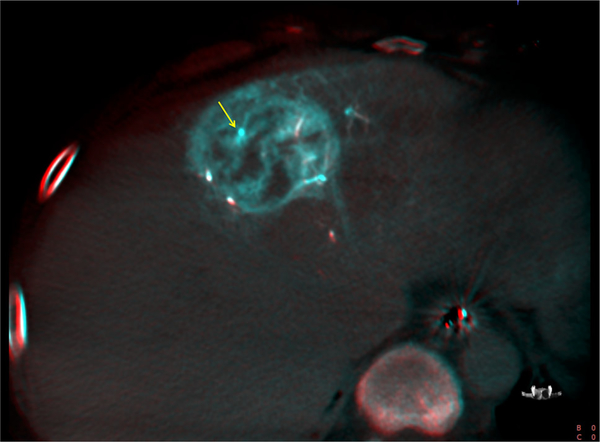

Fig. 15.

Patient 3: DSA post-embolization demonstrates subtraction artifact from the embolization microbeads and persistent enhancement (yellow arrow) in the inferior and posterior dominant tumor mass

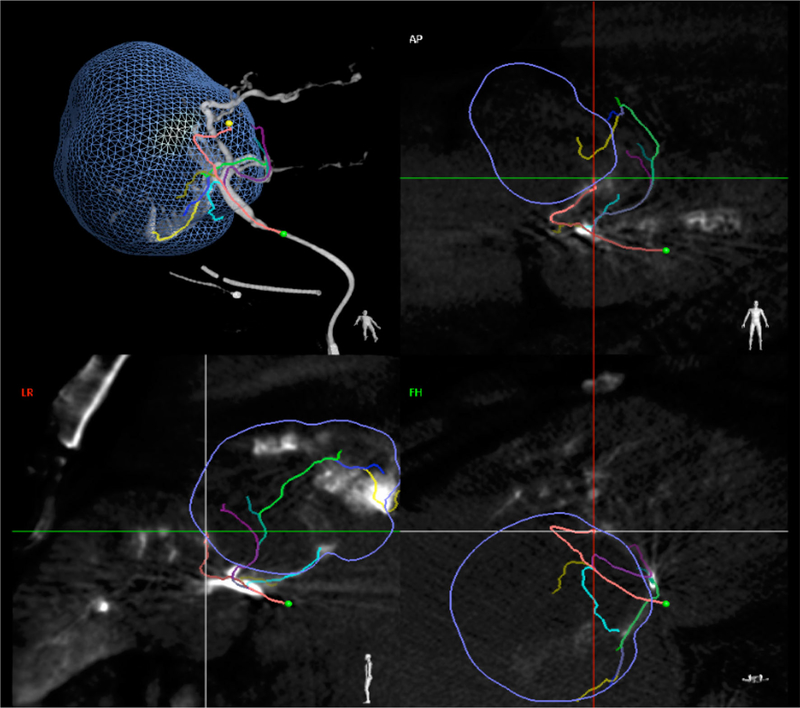

Fig. 13.

Patient 3: emboguide image showing segmented target tumor (blue outline) and autodetected feeding vessels (curvilinear colored lines) in multiple projections

Fig. 14.

Patient 3: coronal non-contrast MIP CBCT image during embolization showing microbeads throughout the majority of the dominant tumor

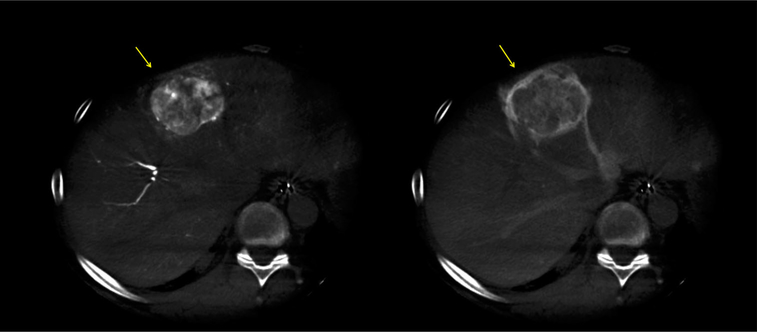

Fig. 16.

Patient 3: Non-contrast (left) and post-contrast (right) CT 48 h after LC LUMI™ embolization reveals an inferior tumor zone with a paucity of microspheres (left, yellow arrow) and corresponding persistent, perfused, and viable inferior tumor (right, yellow arrow)

Procedural Techniques and Imaging Observations

For each procedure, dual-phase cone beam CT imaging of the liver was obtained with the arteriographic catheter in the common or proper hepatic artery (120 kV, 250 mA with automatic modulation, 8 s scan time, 480 projections, 4 × 4 binning, 0.6 mm isotropic voxel size, 25 × 25 × 19 cm FOV). CBCT was obtained 5 s after initiation of contrast injection (arterial phase), and 10 s after completion of the first CBCT data acquisition (parenchymal phase). Isovue 300 contrast was injected at 2 cc/s for 26 cc total volume. Emboguide vessel-tracking software identified the feeding hepatic arteries after segmentation of the target tumors, and the three-dimensional roadmap was displayed with the model superimposed and registered with live fluoroscopy. A 2.8 Fr coaxial microcatheter was advanced to the prescribed location for embolization according to the registered fluoroscopy and plan. Satisfactory catheter tip position was confirmed by digital subtraction arteriography. 70–150 μ LC Bead LUMI™ microbeads were prepared according to manufacturer’s guidelines (2 ml sedimented bead volume diluted 10:1 in 20 ml Omnipaque 350 contrast). Very small aliquots of suspended microbeads were very slowly administered under fluoroscopic control, taking care to not reflux. The rate of microbead injection was approximately 20 ml of bead suspension per hour (0.3 ml of 10:1 suspension per minute), which was sufficiently slow to prevent demonstration of individual microbead boluses and to allow for complete clearance prior to the next bolus. The embolization endpoint was near flow stasis determined angiographically (3 heart beat stasis). The procedure was monitored using fluoroscopy, single-shot digital radiography (SSD) during bead injection, digital subtraction angiography (DSA) to assess residual flow and estimate distribution of contrast plus beads. DSA was not performed with power injection to avoid displacement or redistribution of image-able microbeads. CBCT was performed immediately and 10 min after the final injection of the beads using a custom scan acquisition protocol developed to optimize LC Bead LUMI™ microbead conspicuity (FD20, Allura Clarity, Philips). Imaging was optimized to increase iodine visibility through reduced tube kilovoltage and limiting beam hardening and streak artifacts while maintaining a fast acquisition speed.

Monitoring of the LC Bead LUMI™ administration revealed the dynamic nature of the embolization process. Conventional fluoroscopy localized the liquid contrast plus LC Bead LUMI™ suspension as antegrade flow slowed as a consequence of embolization. SSD depicted the corresponding peripheral deposition of microbeads, which gradually became more dense and slowly filled from peripheral arteries retrograde back toward the catheter tip. Pausing several minutes in between bolus aliquots allowed more central vessels to become less opaque closer to the catheter tip. This may have been due to peripheral packing as beads migrated more distally. For example, patient #1 had embolization with LC Bead LUMI™ of two subsegmental right hepatic artery branches feeding an area of confluent metastases in segments V and VIII. Initially, the embolization stasis endpoint was reached, but SSD revealed only very peripheral microbead distribution. Repeat DSA several minutes later, however, showed interval resumption of antegrade flow, allowing additional microbeads to subsequently be administered from the same catheter tip position. Radio-opaque beads showed subtraction artifact on DSA, allowing differentiation of bead stasis from persistent flow during the procedure. Unenhanced CBCT performed immediately and 10 min after the completion of embolization (Fig. 5) using the same custom scan acquisition protocol (FD20, Allura Clarity, Philips) showed diminution in perivascular liquid contrast density in contrast to stable intravascular density attributable to beads.

The 48 h CT showed similar distribution and conspicuity of beads within vessels compared to intra-procedural completion CBCT, but more interval washout of the less dense perivascular contrast blush seen during the procedure (Fig. 6). The interval washout was not in the linear presumed vessels, which remained opaque on 48 h CT.

Discussion

First described in 2009, iodinated drug-eluting microbeads have been developed over the past decade, including precise characterization of drug elution profiles, compressibility, handle-ability, image-ability, and methods for use [1–9]. Preclinical studies in normal liver and kidney using two different diameter radiopaque microspheres revealed greater tissue penetration with the smaller, 70–150 μm diameter compared with 100–300 μm microspheres [2], potentially increasing locally delivered drug dose and treatment efficacy. As initially proposed in 2010, image-able microbeads labeled with iodine may be able to identify tissue at risk for under-treatment during procedures. [2] CBCT and fusion tools enable this concept. Current research aims to verify as well as clarify the significance of this intra-procedural information.

For the first time in patients, inherently iodinated image-able microbeads were injected into the hepatic arteries to treat primary and metastatic liver cancer, including hepatocellular carcinoma, carcinoid, and neuroendocrine liver metastases. LC Bead LUMI™ consists of sulfonate-modified polyvinyl alcohol hydrogel microbeads with covalently bound iodine throughout the bead structure. The ability to visualize the exact location of embolization microbeads in clinical settings has not been reported, and the distribution of conventional commercially available embolization microbeads can at best be inferred from static liquid contrast columns, retained contrast in the tumor [10], or effects upon flow rates. With conventional or drug-eluting bead chemoembolization, a vessel may be dense due to filling with static contrast and bead mixture. This static column of retained contrast and bead usually washes out well before subsequent embolization sessions. It is unclear how long LC Bead LUMI™ opacifications will remain. Although tissue ethiodized oil location is a poor predictor of drug levels after chemoembolization [11], it is unproven whether LC Bead LUMI™ could be a better predictor or surrogate marker for drug distribution.

LC Bead LUMI™ suspends well in 100 % contrast (Omnipaque-350 or Visipaque 320), and can be delivered easily via standard microcatheters. Suspension in a contrast/saline mixture does not provide a durable suspension. We observed that microbeads mixed with Omnipaque 350 should be re-suspended about every 30 s to 1 min (if delivered from a 3 ml syringe) to ensure uniform delivery without layering of beads in the injection syringe. Introduction of air bubbles should be judiciously avoided, and the beads should be injected from a horizontal syringe to avoid microcatheter occlusion. Injection should be performed very slowly and patiently, to maximize microbead deposition in the target tumor, to ensure uniform delivery, and to avoid proximal occlusion and non-target reflux. We observed that to inject approximately 2 cc of packed beads (22 ml suspension) over 1 h was slow enough to avoid reflux-related off-target embolization.

Image-able bead delivery can be monitored with fluoroscopy and the distribution can be progressively distinguished with SSD and CBCT. Preclinical studies demonstrated that LC Bead LUMI™ has more conspicuity in vessels on both CBCT and single-shot digital X-ray (and this difference is probably more apparent on CBCT and SSD than on fluoroscopy). The exact duration of the image-ability in patients remains unknown, but in preclinical studies, the radiopacity of LC Bead LUMI™ microbeads on unenhanced CT is unchanged out to 90 days is established (data not shown). Conventional non-contrast CT obtained 48 h after microbead administration confirmed visibility and stable distribution of the microbeads (Table 1).

Table 1.

Procedure characteristics

| Patient number | Procedure | Contrast + volume | Fluoroscopy time (min) |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Right hepatic artery embolization | Isovue 300 90 cc Omnipaque 350 10 cc |

27.8 |

| 2 | Left hepatic artery embolization | Isovue 300 110 cc Omnipaque 350 16 cc |

26.1 |

| 3 | Left hepatic artery embolization | Isovue 300 115 cc | 71.8 |

Tuning of CBCT, SSD, and fluoroscopy for visualizing image-able microbeads was previously performed with preclinical swine models. Optimized microbead visualization permitted integration of bead delivery with navigation and treatment planning tools and software. The density and distribution of radiopaque microbeads may provide additional information to refine embolization endpoint, in addition to degree of flow stasis. Although speculative, it is possible that non-target reflux or off-target small branch infusions will be better identified prospectively with LC Bead LUMI™ than with all prior standard DEB and embolization microbeads. The high-spatial resolution of CBCT may be better suited to monitor non-target embolization and iodinated beads distribution compared to other X-ray techniques.

The feedback provided by image-able microbeads during an embolization procedure may better inform the operator of the future effects of the treatment. LC Bead LUMI™ is directly visualized with CBCT, whereas LC Bead is not [9]. The additional visual information such as that provided by LC Bead LUMI™ may provide tools for standardization and reproducibility of end points and treatment effects. Lack of complete peripheral contrast retention on CBCT within minutes after drug-eluting bead embolization has been reported as a risk factor for treatment failure [10]. Likewise, contrast retention on non-contrast CT immediately post-embolization has been postulated to carry treatment information [12]. Intra-procedural Identification of tissue at risk for under-dosing or under-treatment is a powerful tool that could better inform ways to immediately target this tissue with more microbeads, drug, or ablation needles. Indeed, two of our three patients demonstrated presumably under-treated tumor on the basis of intra-procedural LC Bead LUMI™ distribution on CBCT. Dual-view fusion of pre- and post-CBCT may detect tumor tissue appearing under-treated. The integration of ablation and embolization treatment planning navigation software alongside of an image-able embolic microbead with drug-eluting abilities may enable future combination therapies with the ultimate goal to achieve more complete tumor treatment with more standardized and universal endpoints.’

Acknowledgments

Compliance with Ethical Standards

Conflict of interest The NIH authors are supported by CRADA’s with Philips (B.W.) and with Biocompatibles/BTG (B.W). This work also supported by the Intramural Research Program of the NIH and the Center of Interventional Oncology, Grant/Z Number ZID BC011242-08. NIH may own intellectual property in the field.

References

- 1.Dreher M, Sharma K, Orandi B, Donahue D, Tang Y, Lewis A, Karanian J, Chiesa O, Pritchard W, Wood B. Distribution of image-able beads and doxorubicin following transcatheter arterial chemoembolization. Society of Interventional Radiology annual meeting 2009, San Diego. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Sharma KV, Dreher MR, Tang Y, Pritchard W, Chiesa OA, Karanian J, Perogoy J, Orandi B, Woods D, Donahue D, Esparza J, Jones G, Willis SL, Lewis AL, Wood B. Development of "image-able" beads for transcatheter embolotherapy. J Vasc Interv Radiol. 2010;21:865–76. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Dreher MR, Sharma KV, Woods DL, Reddy G, Tang Y, Pritchard WF, Chiesa OA, Karanian JW, Esparza JA, Donahue D, Levy EB, Willis SL, Lewis AL, Wood BJ. Radiopaque drug-eluting beads for transcatheter embolotherapy: experimental study of drug penetration and coverage in swine. J Vasc Interv Radiol. 2012;23(2):257–64. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Tacher V, Lin M, Bhagat N, Abi Jaoudeh N, Radaelli A, Noordhoek N, Carelsen B, Wood BJ, Geschwind JF. Dual-phase cone-beam computed tomography to see, reach, and treat hepatocellular carcinoma during drug-eluting beads transarterial chemo-embolization. J Vis Exp. 2013;82:50795. doi: 10.3791/50795. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Johnson CG, Tang Y, Beck A, Dreher MR, Woods DL, Negussie AH, Donahue D, Levy EB, Willis SL, Lewis AL, Wood BJ, Sharma KV. Preparation of radiopaque drug-eluting beads for transcatheter chemoembolization. J Vasc Interv Radiol. 2016;27(1):117–26. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Negussie AH, Dreher MR, Johnson CG, Tang Y, Lewis AL, Storm G, Sharma KV, Wood BJ. Synthesis and characterization of image-able polyvinyl alcohol microspheres for image-guided chemoembolization. J Mater Sci Mater Med. 2015;26(6):198. doi: 10.1007/s10856-015-5530-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Lewis AL, Dreher MR, O’Byrne V, Grey D, Caine M, Dunn A, Tang Y, Hall B, Fowers KD, Johnson CG, Sharma KV, Wood BJ. DC BeadM1™M: towards an optimal transcatheter hepatic tumour therapy. J Mater Sci Mater Med. 2016;27(1):13. doi: 10.1007/s10856-015-5629-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Tacher V, Duran R, Lin M, Sohn JH, Sharma KV, Wang Z, Chapiro J, Gacchina Johnson C, Bhagat N, Dreher MR, Schäfer D, Woods DL, Lewis AL, Tang Y, Grass M, Wood BJ, Geschwind JF. Multimodality imaging of ethiodized oil-loaded radiopaque microspheres during transarterial embolization of rabbits with VX2 liver tumors. Radiology. 2015;2015:141624. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Duran R, Sharma K, Dreher MR, Ashrafi K, Mirpour S, Lin M, Schernthaner RE, Schlachter TR, Tacher V, Lewis AL, Willis S, den Hartog M, Radaelli A, Negussie AH, Wood BJ, Geschwind JF. A novel inherently radiopaque bead for transarterial embolization to treat liver cancer—a pre-clinical study. Theranostics. 2016;6(1):28–39. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Suk OhJ, Jong Chun H, Gil Choi B, Giu Lee H. Transarterial chemoembolization with drug-eluting beads in hepatocellular carcinoma: usefulness of contrast saturation features on cone-beam computed tomography imaging for predicting short-term tumor response. J Vasc Interv Radiol. 2013;24(4):483–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Gaba RC, Baumgarten S, Omene BO, van Breemen RB, Garcia KD, Larson AC, Omary RA. Ethiodized oil uptake does not predict doxorubicin drug delivery after chemoembolization in VX2 liver tumors. J Vasc Interv Radiol. 2012;23(2):265–73. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Golowa YS, Cynamon J, Reinus JF, Kinkhabwala M, Abrams M, Jagust M, Chernyak V, Kaubisch A. Value of noncontrast CT immediately after transarterial chemoembolization of hepatocellular carcinoma with drug-eluting beads. J Vasc Interv Radiol. 2012;23(8):1031–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]