Abstract

Objective

We previously described lower leg lean mass Z-scores (LLMZ) in Fontan patients associated with worse peak oxygen consumption on metabolic exercise testing. We hypothesised that LLMZ correlates with indexed systemic flow (Qsi) and cardiac index (CI) on exercise cardiac magnetic resonance (eCMR).

Methods

Thirteen patients had LLM measured by dual-energy X-ray absorptiometry within mean 40 (range 0–258) days of eCMR. LLM was converted to sex and race-specific Z-scores based on healthy reference data. Ventricular volumes and flow measurements of the ascending and descending (DAO) aorta and superior vena cava (SVC) were obtained by CMR at rest and just after supine ergometer exercise to a heart rate associated with anaerobic threshold on prior exercise test. Baseline and peak exercise measures of Qsi (SVC+DAO/BSA) and CI, as well as change in Qsi and CI with exercise, were compared with LLMZ by linear regression.

Results

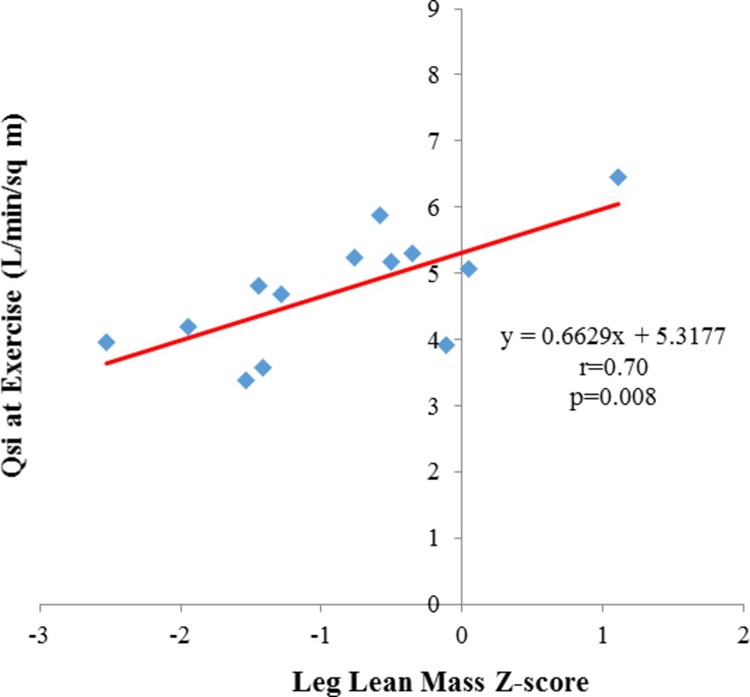

LLMZ was not correlated with resting flows, stroke volume or CI. There was a strong linear correlation between LLMZ and change in both CI (r=0.77, p=0.002) and Qsi (r=0.73, p=0.005) from rest to exercise. There was also a significant correlation between LLMZ and Qsi at exercise (r=0.70, p=0.008). The correlation between LLMZ and CI at exercise did not reach significance (r=0.3, p=0.07).

Conclusions

In our cohort, there was a strong linear correlation between LLMZ and change in both CI and Qsi from rest to exercise, suggesting that Fontan patients with higher LLMZ may be better able to augment systemic output during exercise, improving performance.

Introduction

Over the last four decades since its initial description,1 the Fontan operation has evolved as the final palliative procedure for various types of single ventricle congenital heart disease. While life expectancy has improved markedly, patients with Fontan physiology face many challenges. Poor exercise performance, objectively measured by decreased peak oxygen consumption (VO2), is well documented in these patients.2–4 However, there is considerable variability; many patients have severely diminished exercise capacity, while others perform well or even superiorly.2 This variability in exercise performance among Fontan patients is incompletely understood. Tangible determinants of exercise capacity include ‘central’ (cardiovascular) and ‘peripheral’ (skeletal muscle) factors. Impaired stroke volume is thought to be the primary cardiovascular determinant of low VO2, accounting for 73% of the percent predicted peak VO2.2 However, despite this appreciation for the cardiovascular determinants of peak VO2 in Fontan patients, the impact of peripheral factors is unknown.

We previously reported that Fontan patients have lower leg lean mass (a marker of skeletal muscle) compared with healthy reference patients, and that leg lean mass Z-score (LLMZ) positively correlates with peak VO2 on upright metabolic exercise test in Fontan patients.5 Additionally, stroke volume and cardiac index (CI) at exercise as measured by cardiac magnetic resonance (CMR) are associated with exercise performance in Fontan patients.6 We sought to explore the mechanism by which leg lean mass influences exercise performance and hypothesised that LLMZ would correlate with CI at exercise and the change in CI from rest to exercise as measured on exercise CMR (eCMR).

Materials and methods

Fontan participants>12 years old were prospectively enrolled in an eCMR protocol.7 Subjects were eligible if they had Fontan physiology and were able to undergo metabolic exercise test using a stationary cycle ergometer. Exclusion criteria included pacemaker, defibrillator or metal hardware that prevented adequate CMR imaging. Thirteen participants from the eCMR protocol also consented to participate in a cross-sectional study of growth and body composition between July 2011 and October 2013, as previously reported.5 In the body composition study, Fontan participants were compared with a cohort of 992 healthy reference participants (ages 5 to 30 years) from the greater Philadelphia area from whom anthropometric measures and measures of body composition were collected.8,9 Pertinent demographic and anatomic variables were obtained through patient interviews and confirmed in the medical record. Written, informed consent was obtained from participant or parent/guardian in all cases. The study protocol was approved by the Institutional Review Board at The Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia.

Exercise CMR protocol

Patients first completed a ramp metabolic exercise test on an electronically braked ergometer (Ergometrics 800, SensorMedics, Yorba Linda, California, USA) or a 1 min incremental treadmill according to our standard protocol.2 Metabolic data were obtained throughout the study and for the first 2 min of recovery on a breath-by-breath basis by using a metabolic cart (SensorMedics V29). The ventilatory anaerobic threshold was measured by the V-slope method.

The patients subsequently completed the resting and exercise CMR protocol which has been previously described.5,7 Briefly, the resting protocol consisted of a contiguous axial stack of static steady-state-free precession images used for multiplanar anatomic reconstruction, both segmented and free-breathing real-time cine short-axis stacks, and through-plane retrospectively gated phase-contrast magnetic resonance with respiratory compensation across the superior and inferior vena cavae, descending aorta at the level of the diaphragm, aortic (or neo-aortic) valve and branch pulmonary arteries. After resting CMR acquisition, the patients were slid partially out from the magnetic resonance bore to perform lower limb exercise using an magnetic resonance-compatible supine bicycle ergometer (Lode BV, Groningen, the Netherlands). Heart rate was monitored continuously. The initial workload of 20 W was increased 20 W/min to achieve the heart rate associated with ventilatory anaerobic threshold on prior metabolic exercise test. Exercise was suspended, the patient’s feet were removed from the ergometer pedals and the patient was returned to isocenter for imaging (generally within 5–10 s). A real-time cine short-axis stack was performed with the following parameters: integrated parallel imaging technique (IPAT) 3–4, 160/128 matrix, TR 50–55. This method has been previously validated against breath-held segmented short-axis imaging.10,11 As the patients could not breath-hold uniformly after exercise, respiratory-averaged segmented phase-contrast magnetic resonance measurements of the aorta, superior vena cava and descending aorta flow were performed. Descending aorta flow was substituted for inferior vena caval flow due to difficulty in maintaining inferior vena cava position at exercise.12 Flows and volumes were segmented using ARGUS software (Siemens) and were indexed to body surface area. Cardiac output was calculated as the product of stroke volume (end-diastolic volume minus end-systolic volume) and heart rate; cardiac output was indexed to body surface area to determine CI. Indexed systemic flow (Qsi) was defined as the sum of superior vena cava and descending aorta flow indexed to body surface area.

Anthropometric measures and dual-energy X-ray absorptiometry scans

At the time of the visit for dual-energy X-ray absorptiometry scan, weight was measured using a digital scale (ScaleTronix, White Plains, New York, USA). Height and sitting height were measured using a stadiometer (Holtain, Crosswell, Crymych, UK) and used to calculate leg length (leg length=height − sitting height).

Whole body lean and fat mass were measured with a Hologic Delphi densitometer (Bedford, Massachusetts, USA) with a fan beam in the array mode (software version 12.4), excluding the head. Measurements were performed with standard supine positioning techniques. Lean mass was calculated as fat-free mass minus bone mineral content; leg lean mass was used as a measure of skeletal muscle. Calibration was performed daily with a hydroxyapatite phantom and weekly with a whole-body phantom. Coefficients of variation ranged from 1% to 4%.

Statistical analysis

As previously described,5 height was converted to sex-specific Z-scores (standard deviation scores) relative to age using the 2000 National Center for Health Statistics growth data.13 Height Z-scores in participants≥20 years of age (the upper bound of the reference data) were generated relative to a 20 year old. Fontan lean mass was converted to sex and race-specific Z-scores relative to age using the LMS method based on reference participant data.14 Body composition measures are highly correlated with height, and Fontan physiology is associated with impaired linear growth. Therefore, the LLMZs were adjusted for leg length Z-score.15 This adjustment addresses the significant linear growth failure observed in childhood chronic diseases.

Changes in exercise parameters from rest to exercise were assessed via Student’s t-test. Baseline and peak exercise measures of Qsi and CI, as well as change in Qsi and CI with exercise, were compared with LLMZ by linear regression. Analyses were performed using Stata V.12.0 (Stata). A p value<0.05 was considered significant and two-sided tests were used throughout.

Results

Thirteen patients consented to participate. Participants’ demographic and clinical characteristics are listed in table 1. LLMZ was measured by dual-energy X-ray absorptiometry within mean 40 days (range 0–258) of eCMR protocol. Nearly all (12 of 13, 92%) participants underwent dual-energy X-ray absorptiometry within 4 months of eCMR, the majority within 1 week. All participants underwent metabolic exercise test within 6 months of eCMR; 10 participants (77%) underwent metabolic exercise test and eCMR the same week.

Table 1.

Demographic and clinical characteristics, n=13

| Variable | Value |

|---|---|

| Age, median (range) year | 17.7 (12.7–26) |

| Male, n (%) | 7 (54) |

| Race, n (%) | |

| White | 9 (69) |

| Black | 4 (31) |

| Systemic ventricular morphology, n (%) | |

| Right | 3 (23) |

| Left | 7 (54) |

| Mixed | 3 (23) |

| Type of Fontan, n (%) | |

| Extracardiac conduit | 5 (38) |

| Lateral tunnel | 8 (62) |

| Fenestration at time of initial Fontan | 9 (69) |

| Body surface area, m2, mean±SD | 1.65±0.25 |

| Height Z-score, mean±SD | −0.33±1.13 |

| Range | −2.48 to 0.85 |

| LLMZ, mean±SD | −0.87±0.95 |

| Range | −2.53 to 1.11 |

| Previous metabolic exercise test | |

| Peak VO2, mL/(kg · min) | 29±7 |

| VO2 at anaerobic threshold, mL/(kg · min)* | 17±3 |

| Oxygen pulse, mL | 10.6±3.2 |

One patient did not achieve anaerobic threshold.

LLMZ, leg lean mass Z-score; VO2, oxygen consumption.

Nine participants (69%) were treated with ACE inhibitors during the study period. No patient was taking a phosphodiesterase-5 inhibitor.

CMR haemodynamic parameters at rest and exercise are detailed in table 2. There was a statistically significant change from rest to exercise for heart rate, indexed stroke volume, CI, superior vena caval and descending aortic flows, and Qsi. There was no change in indexed end-diastolic or end-systolic volumes from rest to exercise; the change in ejection fraction trended towards significance.

Table 2.

CMR haemodynamic parameters at rest and exercise*

| Rest | Exercise | Change from rest to exercise | p Value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Heart rate, bpm | 64±16 | 94±22 | 29±13 | p<0.001 |

| Indexed end-diastolic volume, mL/m2 | 78±18 | 83±13 | 5±7 | p=0.44 |

| Indexed end-systolic volume, mL/m2 | 28±13 | 24±10 | −4±6 | p=0.36 |

| Indexed stroke volume†, mL/m2 | 50±10 | 59±8 | 9±6 | p=0.018 |

| Ejection fraction, % | 65±10 | 72±8 | 7±6 | p=0.07 |

| Cardiac index, L/min/m2 | 3.1±0.7 | 5.5±1.3 | 2.4±0.9 | p<0.0001 |

| SVC flow, L/min | 1.1±0.3 | 1.9±0.7 | 0.7±0.7 | p=0.004 |

| DAO flow, L/min | 3.1±0.6 | 6±1.4 | 2.9±1.0 | p<0.0001 |

| Qsi, L/min/m2 | 2.6±0.4 | 4.7±0.9 | 2.2±0.8 | p<0.0001 |

All parameters are expressed as mean±1 SD.

By real-time cine imaging.

bpm, beats per minute; CMR, cardiac magnetic resonance; DAO, descending aorta; Qsi, systemic flow indexed to body surface area; SVC, superior vena cava.

There was a strong linear correlation between LLMZ and Qsi at exercise (r=0.7, p=0.008; figure 1), change in Qsi from rest to exercise (r=0.73, p=0.005; figure 2A) and change in CI from rest to exercise (r=0.77, p=0.002; figure 2B). The correlation between LLMZ and CI at exercise did not reach statistical significance (r=0.52, p=0.067).

Figure 1.

There was a strong linear correlation between LLMZ and Qsi at exercise. LLMZ, leg lean mass Z-score; Qsi, indexed systemic flow.

Figure 2.

There was a strong linear correlation between LLMZ and change in both Qsi (A) and CI (B) from rest to exercise. LLMZ, leg lean mass Z-score; Qsi, indexed systemic flow.

There was no significant correlation between LLMZ and resting heart rate, indexed stroke volume, CI or Qsi (r=0.38, p=0.20 for resting heart rate, r = −0.42, p=0.15 for resting indexed stroke volume, r=0.05, p=0.87 for resting CI, r=0.11, p=0.72 for resting Qsi). There was a moderate linear statistically significant correlation between LLMZ and exercise heart rate (r=0.57, p=0.04), while there was no significant correlation between LLMZ and change in heart rate from rest to exercise (r=0.45, p=0.13), indexed stroke volume at exercise (r=−0.19, p=0.54) or change in indexed stroke volume from rest to exercise (r=0.47, p=0.10).

There was no significant difference between the heart rate reached at anaerobic threshold on prior metabolic exercise test and exercise heart rate on eCMR (109±20 beats per minute vs 96±22 beats per minute, p=0.14).

Discussion

In this study, we describe a positive relationship between LLMZ and systemic output at exercise in a small number of Fontan patients undergoing dual-energy X-ray absorptiometry and eCMR. Higher LLMZ was associated with higher Qsi at exercise and greater changes in both Qsi and CI from rest to exercise. The correlation between LLMZ and CI at exercise did not reach statistical significance. These findings increase our appreciation of the peripheral determinants of exercise capacity in Fontan patients and identify a potentially modifiable risk factor for decreased functional capacity in these patients.

Greater lower extremity muscle mass decreases venous compliance and increases systemic venous return, stroke volume and cardiac output in the normal resting circulation.16 The peripheral muscle pump augments systemic venous return at the initiation of exercise in upright individuals with normal cardiorespiratory circulation.17 Since the majority of skeletal muscle is in the legs, LLMZ is a surrogate for skeletal muscle and represents this peripheral pump. Fontan patients have multiple potential risk factors for decreased skeletal muscle mass including haemodynamic abnormalities, nutritional deficiencies, low levels of growth factors,18 chronic medication use and inadequate physical activity19,20 and have been shown to have low LLMZ compared with healthy reference patients.5 Skeletal muscle deficits may be critically important in preload dependent Fontan patients who lack a subpulmonary ventricle and depend on passive filling of the systemic ventricle with pulmonary venous return.

The haemodynamic impact of these deficits is particularly evident during periods of increased demand, such as exercise. In our study, there was no correlation between LLMZ and resting volumes or flows. However, exercise exposes the importance of skeletal muscle defects. Greater LLMZ was associated with greater change in Qsi and CI from rest to exercise. As stroke volume is believed to be the primary cardiac determinant of exercise capacity in Fontan patients,2 these results suggest that greater LLMZ may improve ventricular filling, stroke volume and cardiac output at exercise. Better LLMZ may allow some Fontan patients to positively augment their response to exercise, although the link between eCMR-derived CI/Qsi and peak upright exercise capacity needs to be verified. Our preliminary eCMR data demonstrate that stroke volume and CI at exercise are positively associated with VO2 on metabolic exercise test in Fontan patients.6 Should the link between exercise CI/Qsi and VO2 on metabolic exercise test be verified, targeted interventions to improve LLMZ may be expected to improve Fontan exercise performance.

We hypothesised that LLMZ would correlate with both CI and Qsi at exercise. While LLMZ was correlated with the change in both CI and Qsi from rest to exercise, only Qsi at exercise was correlated with LLMZ. The correlation between LLMZ and CI at exercise did not reach statistical significance. The explanation for this finding may be twofold. After cavopulmonary connection, patients may demonstrate substantial systemic-to-pulmonary arterial collateral flow.21 While the relationship between collateral flow burden and exercise capacity is not clear, higher collateral flow burden has been associated with adverse outcomes after Fontan, especially longer length of stay and prolonged pleural effusions.22–24 Several groups, including several of the present authors, have described a method of quantifying collateral flow by phase-contrast MR.25,26 In the absence of significant atrioventricular valve regurgitation, the stroke volume of the systemic ventricle is comparable to the flow across the neo/aortic valve. As aortic flow includes the systemic-to-pulmonary collateral flow, systemic blood flow is more accurately measured by the sum of the superior vena caval and inferior vena caval/descending aorta flow returning to the heart rather than by CI. The positive correlation between LLMZ and Qsi at exercise may represent augmentation of true systemic output in response to the demands of exercise.

The lack of correlation between LLMZ and CI at exercise may also be due to the study’s small sample size. While there was a moderate correlation between LLMZ and exercise heart rate, there was no correlation between LLMZ and exercise stroke volume (indexed) or change in stroke volume from rest to exercise. These findings may reflect the variability in Fontan sinus node function, such that some participants demonstrate a greater heart rate response to exercise while the stroke volume response is greater in others. Correlations between LLMZ and exercise stroke volume/CI may reach statistical significance in a larger study.

Our findings generate additional questions regarding the effect of exercise training on Fontan systemic cardiac output and exercise performance. Several small studies have explored the impact of aerobic exercise training on Fontan exercise capacity with varied results.27,28 Fewer investigators have considered the effect of resistance training on Fontan patients. Cordina and colleagues identified skeletal muscle deficits in association with worse VO2 in adult Fontan patients.29 A small group of adult Fontan patients underwent metabolic exercise test, dual-energy X-ray absorptiometry and free-breathing CMR. Six patients participated in a 20-week high-intensity resistance training programme. Due to a technical issue, the investigators were not able to adequately analyse the difference in haemodynamic parameters between baseline and the trained state. However, after a 12-month detraining period, the patients demonstrated a significant decrease in leg muscle mass, VO2 and oxygen pulse, a surrogate for stroke volume. The authors concluded that resistance muscle training improves muscle mass and strength, and is associated with improved cardiac filling, stroke volume and exercise capacity.30 Future studies in adolescent and young adult Fontan patients should prospectively examine the impact of lower extremity exercise training programme on the various peripheral and central components of exercise performance.

There are several limitations to our study. First, the sample size was small. Performing multiple t-tests to compare haemodynamic parameters at rest and exercise in this small sample may produce false positive results. Additionally, a larger study may identify correlations between LLMZ and resting measures of cardiac output or between LLMZ and stroke volume or CI at exercise. Alternatively, the expected correlations between LLMZ and exercise CI/Qsi could be affected by the relative amounts of systemic output distributed to non-exercising vascular beds, particularly the splenic beds, whose flows during exercise are independent of LLMZ. Importantly, there are limitations to the study’s findings given the study’s cross-sectional design as well as the lack of data regarding participants’ habitual exercise. Higher LLMZ may have been a reflection of greater motivation to participate in habitual exercise, which could have impacted participants’ overall conditioning and central determinants of exercise capacity. Importantly, some patients with superior haemodynamic conditions (better ventricular performance, lower pulmonary vascular resistance, greater capacity to increase chronotropy) that result in improved exercise capacity may engage in more regular physical activity and accrue lower extremity muscle mass as a result. Finally, the eCMR data were not acquired at ‘true’ peak exercise. The design of our supine ergometer is such that exercise is performed just outside the CMR bore and the patient is returned to the bore as quickly as possible to obtain the exercise sequences. Care was taken to slide the patient back into the bore within 5–10 s; however, the exercise data may be somewhat misrepresented due to the design of the ergometer. There may also be some limitations translating this supine exercise data to real-life upright exercise performance.

In conclusion, this study demonstrates a positive relationship between leg muscle mass and change in CI/Qsi with exercise in a small group of Fontan patients. The findings suggest that interventions to increase lower extremity lean muscle mass may augment cardiac output and could improve exercise performance in these patients. The link between eCMR-derived CI/Qsi and peak upright exercise capacity should be explored in the future.

Key messages.

What is already known on this subject?

Poor exercise performance, objectively measured by decreased peak oxygen consumption (VO2), is well documented in Fontan patients but the variability in performance among individuals is poorly understood. Our group and others29 have identified lower extremity skeletal muscle deficits in association with worse VO2 in Fontan patients; however, the mechanisms by which leg lean mass/skeletal muscle deficits influence exercise performance in this population are not well understood.

What might this study add?

This study demonstrates a strong linear correlation between leg lean mass Z-score and change in both cardiac index and indexed systemic flow from rest to exercise using an magnetic resonance-compatible supine bicycle ergometer. These results suggest that Fontan patients with greater leg lean mass may be better able to augment systemic output during exercise, improving performance and suggest a potentially modifiable risk factor for decreased functional capacity in these patients.

How might this impact on clinical practice?

The study’s findings generate additional questions regarding the effect of exercise training on Fontan systemic cardiac output and exercise performance. Our findings suggest that interventions to increase lower extremity lean muscle mass may augment cardiac output and improve exercise performance in Fontan patients.

Funding

Funding was provided by a Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia Cardiac Center Grant as well as support from the Robert S. and Dolores Harrington Endowment in Pediatric Cardiology at The Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia and by NIH grants T32 HL007915 (CA), K23 HL089647 (KKW), K24 DK0768084 (MBL), R01 HL098252–01 (MBL), R01 HL098252 (APY, MAF) and Clinical and Translational Science Award UL1 RR024134 and UL1 TR000003.

Footnotes

Provenance and peer review Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

References

- 1.Fontan F, Baudet E. Surgical repair of tricuspid atresia. Thorax 1971;26:240–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Paridon SM, Mitchell PD, Colan SD, et al. A cross-sectional study of exercise performance during the first 2 decades of life after the Fontan operation. J Am Coll Cardiol 2008;52:99–107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Giardini A, Hager A, Pace Napoleone C, et al. Natural history of exercise capacity after the Fontan operation: a longitudinal study. Ann Thorac Surg 2008;85:818–21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Fernandes SM, McElhinney DB, Khairy P, et al. Serial cardiopulmonary exercise testing in patients with previous Fontan surgery. Pediatr Cardiol 2010;31:175–80. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Avitabile CM, Leonard MB, Zemel BS, et al. Lean mass deficits, vitamin D status and exercise capacity in children and young adults after fontan palliation. Heart 2014;100:1702–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Whitehead KK, Khiabani R, Harris MA, et al. Stroke volume and cardiac index at exercise as measured by cardiac magnetic resonance predicts metabolic exercise performance. American HeartAssociation Annual Scientific Sessions 2013 2017;33:410–9. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Khiabani RH, Whitehead KK, Han D, et al. Exercise capacity in single-ventricle patients after Fontan correlates with haemodynamic energy loss in TCPC. Heart 2015;101:139–43. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Mostoufi-Moab S, Ginsberg JP, Bunin N, et al. Body composition abnormalities in long-term survivors of pediatric hematopoietic stem cell transplantation. J Pediatr 2012;160:122–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Baker JF, Davis M, Alexander R, et al. Associations between body composition and bone density and structure in men and women across the adult age spectrum. Bone 2013;53:34–41. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Lee VS, Resnick D, Bundy JM, et al. Cardiac function: MR evaluation in one breath hold with real-time true fast imaging with steady-state precession. Radiology 2002;222:835–42. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kühl HP, Spuentrup E, Wall A, et al. Assessment of myocardial function with interactive non-breath-hold real-time MR imaging: comparison with echocardiography and breath-hold Cine MR imaging. Radiology 2004;231:198–207. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Wei Z, Whitehead KK, Khiabani RH, et al. Respiratory effects on fontan circulation during rest and exercise using real-time cardiac magnetic resonance imaging. Ann Thorac Surg 2016;101:1818–25. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ogden CL, Kuczmarski RJ, Flegal KM, et al. Centers for disease control and prevention 2000 growth charts for the united states: improvements to the 1977 national center for health statistics version. Pediatrics 2002;109:45–60. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Cole TJ. The LMS method for constructing normalized growth standards. Eur J Clin Nutr 1990;44:45–60. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Zemel BS, Leonard MB, Kelly A, et al. Height adjustment in assessing dual energy x-ray absorptiometry measurements of bone mass and density in children. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 2010;95:1265–73. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Convertino VA, Doerr DF, Flores JF, et al. Leg size and muscle functions associated with leg compliance. J Appl Physiol 1988;64:1017–21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Wang Y, MARSHALL RJ, Shepherd JT. The effect of changes in posture and of graded exercise on stroke volume in man. J Clin Invest 1960;39:1051–61. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Avitabile CM, Leonard MB, Brodsky JL, et al. Usefulness of insulin like growth factor 1 as a marker of heart failure in children and young adults after the Fontan palliation procedure. Am J Cardiol 2015;115:816–20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Longmuir PE, Russell JL, Corey M, et al. Factors associated with the physical activity level of children who have the Fontan procedure. Am Heart J 2011;161:411–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.McCrindle BW, Williams RV, Mital S, et al. Physical activity levels in children and adolescents are reduced after the Fontan procedure, independent of exercise capacity, and are associated with lower perceived general health. Arch Dis Child 2007;92:509–14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.McElhinney DB, Reddy VM, Tworetzky W, et al. Incidence and implications of systemic to pulmonary collaterals after bidirectional cavopulmonary anastomosis. Ann Thorac Surg 2000;69:1222–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Glatz AC, Rome JJ, Small AJ, et al. Systemic-to-pulmonary collateral flow, as measured by cardiac magnetic resonance imaging, is associated with acute post-Fontan clinical outcomes. Circ Cardiovasc Imaging 2012;5:218–25. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Grosse-Wortmann L, Drolet C, Dragulescu A, et al. Aortopulmonary collateral flow volume affects early postoperative outcome after Fontan completion: a multimodality study. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg 2012;144:1329–36. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Odenwald T, Quail MA, Giardini A, et al. Systemic to pulmonary collateral blood flow influences early outcomes following the total cavopulmonary connection. Heart 2012;98:934–40. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Whitehead KK, Gillespie MJ, Harris MA, et al. Noninvasive quantification of systemic-to-pulmonary collateral flow: a major source of inefficiency in patients with superior cavopulmonary connections. Circ Cardiovasc Imaging 2009;2:405–11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Grosse-Wortmann L, Al-Otay A, Yoo SJ. Aortopulmonary collaterals after bidirectional cavopulmonary connection or Fontan completion: quantification with MRI. Circ Cardiovasc Imaging 2009;2:219–25. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Rhodes J, Curran TJ, Camil L, et al. Impact of cardiac rehabilitation on the exercise function of children with serious congenital heart disease. Pediatrics 2005;116:1339–45. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Opocher F, Varnier M, Sanders SP, et al. Effects of aerobic exercise training in children after the Fontan operation. Am J Cardiol 2005;95:150–2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Cordina R, O’Meagher S, Gould H, et al. Skeletal muscle abnormalities and exercise capacity in adults with a Fontan circulation. Heart 2013;99:1530–4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Cordina RL, O’Meagher S, Karmali A, et al. Resistance training improves cardiac output, exercise capacity and tolerance to positive airway pressure in Fontan physiology. Int J Cardiol 2013;168:780–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]