Abstract

The coronavirus disease (COVID-19) has spread worldwide in a short period and has developed into one of the biggest public health issues of the last decade. The actions initiated by governments to minimize person-to-person contact have also severely affected professional football clubs (PFCs) in the season 2019/20. Given the role of football in Europe, football clubs gained massive public and political attention during the COVID-19 crisis. Based on an exploratory multiple case study approach involving PFCs from five European football leagues, this study investigates the responses of these clubs to the COVID-19 pandemic. The findings show the relevance of solidarity with certain stakeholders during the pandemic, but also reveal the fragility of PFCs due to their financial structure and underdeveloped managerial and entrepreneurial strategies to cope with the crisis. This study contributes theoretically and empirically to the literature on the entrepreneurial behavior and crisis management of elite sport organizations and illustrates a holistic map of a dense, high solidary stakeholder network.

Keywords: Football, Soccer, Professional, Europe, COVID-19, Sport entrepreneurship, Crisis management, Innovation

1. Introduction

The new coronavirus disease (COVID-19) continues to be a threat to humanity due to its continuous spread. The severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2) originated in wild animals (Singhal, 2020) has caused an alarming global health crisis and since its transmission to humans. COVID-19 has already taken millions of lives (WHO, 2020), and hence challenged many governments across the globe to take actions to reduce the spread of the virus. The most widespread governmental measure is social distancing, a way to keep person-person distance to limit the spread of the virus (Sharma, Singh, Sharma, Jones, Kraus & Dwivedi, 2020). In many regions, social distancing measures have similarities to quarantine, and therefore have a dramatic impact on people's everyday lives (Clark, Davila, Regis & Kraus, 2020). Most of the European countries, for example, have closed their schools, universities, and sport facilities; some countries even had a complete lockdown situation and people must stay at home, and nearly every government prohibited public events – including all kinds of sport matches (Breier et al., 2021).

In this context, it has also been seen that all types of organizations have been suffering from the pandemic, including professional sport companies such as football (soccer) companies. As regards the latter, football companies, rather than sport clubs, have a significant impact on the economy of many countries. Presently, football is the kind of sports with the greatest participation, impact, and income worldwide which influences not only the field of sports but also the social area, economics, and even cultural sectors (Escamilla-Fajardo et al., 2020).

The effects of COVID-19 have led to a collapse of revenues and elite football clubs are struggling to contain the economic impact of the COVID-19 pandemic. Additionally, the football industry is more cautious than other industries in its view of potential COVID-19 recovery scenarios; as the football sector is not sustainable without the presence of the fans. Knock-on effects of the pandemic have hit football especially hard and clubs are rather downbeat when considering their prospects over the next season. Public health interventions, like social distancing measures, are effective but do not prevent virus reoccurrences (Sharma et al., 2020). Even though governmental economic interventions have shown to be partially effective, they will not lead to a recovery to pre-crisis levels.

Giving the specific nature of professional football organizations, we see a need for more rigorous research aimed at showing how this category of elite sport clubs is coping with COVID-19. By doing so, we are responding to Parnell's (2020) recent call for research on the impact of COVID-19 in the context of elite sport from different perspectives and types of organizations. Recent research has also attempted to analyze and forecast the effects of the COVID-19 crisis on the economy in different contexts (Baldwin, 2020; Kraus et al., 2020; McKibbin & Fernando, 2020) – by focusing on sport organizations, we further contribute to this debate.

More specifically, this study aims to develop an initial understanding of crisis management in professional football clubs (PFCs) from five different European countries (Austria, Germany, Sweden, Switzerland, and the Netherlands) by analyzing how they perceived and responded to COVID-19 in the 2019/20 season. PFCs are rather match win than profit maximizers, and they generally calculate only low profits (Garcia-del-Barrio & Szymanski, 2009). In addition, the football sector is highly susceptible to crises, which then promptly threaten their existence due to the club's limited liquidity (Manoli, 2016; Szymanski & Weimar, 2019). However, according to Devece et. al. (2016), entrepreneurial organizations in this sector have the potential to overperform during recessions. Innovativeness and proactiveness - two sub-dimensions of entrepreneurial orientation (Lumpkin & Dess, 1996) - in particular, can enhance organizational performance in times of crisis (Mendoza-Ramírez et al., 2016; Petzold et al., 2019). Following other researchers (e.g. Hemme et al., 2017; Jones et al., 2017), we consider sport as a natural setting for entrepreneurship to occur, and thus propose to add the currently emerging research topic sport entrepreneurship (Hammerschmidt et al., 2020; Huertas González-Serrano et al., 2020) as a promising strategic approach to cope with the COVID-19 crisis. Given the situation that sport entrepreneurship is still a novel area of research, there is also a need for international studies from more than one country or region. By having involved PFCs from five different countries the present study contributes to the research field's further development too.

Against this background, the following study seeks to investigate how and by what means international PFCs are responding to the COVID-19 crisis. To our knowledge, this is the first attempt to foster our understanding of how professional (i.e. elite) football clubs have reacted and adapted to the COVID-19 pandemic. The study contributes to strategic, crisis and change management of sport organizations during the COVID-19 crisis and proposes sport entrepreneurship particularly in times of a crisis for short-term adaption and long-term success. The study further contributes to sport organization research and stresses, even more, the important role of stakeholder management in turbulent times. Finally, the study contributes to sport entrepreneurship research by providing insights into how unexpected external shocks trigger PFCs innovation and change processes.

1.1. The COVID-19 crisis during the football season 2019/20

On the 31 December 2019, China informed the WHO about the outbreak of a new coronavirus, and on 1 January 2020, the Huanan Seafood Wholesale Market was closed (Singhal, 2020). Since then, the COVID-19 has spread rapidly, with an ongoing number of confirmed cases in multiple countries. The development of COVID-19 had a powerful and unprecedented impact on the stock markets too, which consequently crashed (Baker et al., 2020). Countries such as China, Hong Kong, and Singapore have shown that the spread of COVID-19 can be controlled by governmental actions focused on social distancing measures (Anderson et al., 2020).

In Europe, the countries and governments also adopted social distancing measures, and in addition closed commercial business, restricted social gatherings, and limited sporting activities. At the beginning of the crisis, professional sport events continued to take place. The Italian Serie A was not stopped until 11 March 2020, when the first football player in Italy, a country which had already alarmingly high reproduction numbers and fatality rates, was tested positive (Corsini et al., 2020). Because of their age and their physical fitness, professional football players are not exposed to a high risk of death by COVID-19 (Khafaie & Rahim, 2020). However, the coronavirus might lead to long-term health injuries of the lung (Chen et al., 2020), which can affect sporting performance and therefore should try to be avoided at all costs. Football is a team sport with permanent and close contact. Players do encounter each other on the field, in training, and during multiple team activities throughout the day whether with their teammates, the opponent, or the staff (Corsini et al., 2020). This sport fascinates masses of people around the world, who are frequently visiting games and sometimes undertake long journeys to see their favorite team. Travelling is one of the most contributors to disease transmission (Tian et al., 2020). Travelling is especially conducive to disease transmission when it involves mass gatherings. From the perspective of mitigating the spread of COVID-19, the primary arguments against football games are the massive numbers of people who are attending the game and the proximity of the crowd which increases the transmissibility of COVID-19 (Parnell et al., 2020).

As a consequence, policymakers and sport policy leaders postponed or cancelled professional sport events step by step. Moreover, most countries prohibited sporting activity as a consequence of social distancing measures resulting in the cancellation of training activity in professional sport. Leagues from Asia started to suspend match operations, with the Chinese Super League on 22 February 2020 and the Japanese J-League on 24 February 2020. Soon after, the spread of the virus reached Europe. The first affected football league was the Swiss Super League. Governmental orders prohibited major events with more than 1000 participants, which also affected the Euro League game between FC Basel and Eintracht Frankfurt on 19 March 2020. The city of Mönchengladbach banned spectators, making the match between 1. FC Köln and Borussia Mönchengladbach on the 11 March 2020 the first game in German Bundesliga history without fans. Officials of German elite football encouraged the economic importance of the games and insisted on playing on without fans. New information about games without fans, game postponements, or other impacts of the coronavirus on the professional sport were reported daily and, on some days, even hourly. Nearly every league in Europe gradually reacted to the spread of COVID-19 and suspended their game operations, except the 1. Liga in Belarus which was still playing (see Table 1 ). As of 13 March 2020, the five biggest European football leagues in the countries England, France, Germany, and Italy postponed their league matches due to public health concerns. Most of the league officials announced that the leagues will continue within the next weeks or months. For example, the games in Switzerland were prohibited because of a declaration, which first only applied until 15 March 2020. In England, elite football was suspended until at least 3 April 2020, and Germany and Italy planned to continue as of 30 April 2020. The combination of the frequent unexpected and surprising news regarding the suspension of elite football and the optimistic assessments of the continuation of the leagues illustrates the underestimation of the COVID-19 situation at the time.

Table 1.

Situation overview of international leagues during the COVID-19 outbreak.

| Country | League | Suspension* | Planned Restart* | Actual Restart |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| EUROPE | ||||

| Austria | Bundesliga | 18 March 2020 | 2 June 2020 | 02 June 2020 |

| England | Premier League | 12 March 2020 | 12 June 2020 | 17 June 2020 |

| France | Ligue 1 | 13 March 2020 | Cancelled | - |

| Germany | Bundesliga | 13 March 2020 | 16 May 2020 | 16 May 2020 |

| Italy | Serie A | 09 March 2020 | End of June | 22 June 2020 |

| Netherlands | Eredivisie | 12 March 2020 | Cancelled | - |

| Spain | La Liga | 12 March 2020 | 11 June 2020 | 11 June 2020 |

| Sweden | Allsvenskan** | 19 March 2020 | 14 June 2020 | 14 June 2020 |

| Switzerland | Super League | 02 March 2020 | 08 June 2020 | 19 June 2020 |

| INTERNATIONAL | ||||

| Argentina | Superliga | 17 March 2020 | Cancelled | - |

| Australia | A-League | 24 March 2020 | Tbd. | 17 July 2020 |

| Belarus | 1. Liga*** | Season running | - | - |

| China | Super League** | 22 February 2020 | End of June/Beginning of July | 25 July 2020 |

| Japan | J-League | 24 February 2020 | 13 June 2020 | 04 July 2020 |

| Mexico | Liga MX | 16 March 2020 | Tbd. | Cancelled |

| Russia | Premjer-Liga | 17 March 2020 | 21/28 June 2020 | 19 June 2020 |

| Turkey | Süper Lig | 19 March 2020 | 12 June 2020 | 12 June 2020 |

| USA | MLS | 12.03. | Not before 08 June 2020 | 12 August 2020 |

tbd = to be defined; * = Status as of 15 May 2020; ** = Season start; *** = One game was postponed because players are suspected of being infected.

Since then, most of the leagues have been working on plans to resume playing (Table 1). The first phase after the suspension was marked by uncertainty. Then, and in close contact with policymakers, leagues created concepts of hygiene measures, coronavirus testing, and distance rules to restart training and playing. Resuming to play is primarily important because of the economic impact of the consequences of the global pandemic. Games are the most important source of earnings and if they do not take place, the clubs’ incomes decrease drastically (Szymanski & Weimar, 2019). However, the economic costs of staging games without fans, the costs of coronavirus testing, public health concerns, and governmental prohibitions lead to cancellation of elite football leagues in Argentina, Belgium, Netherlands, and later also Mexico (Table 1).

As of 16 May 2020, and after two months of inactivity, the German Bundesliga was the first league resuming the season. However, the restart was bound to strict hygiene protocols which were devised jointly by the Deutsche Fussball Liga (DFL) and policymakers at the highest levels. To be allowed to start team training, clubs have tested their players and staff for the coronavirus and went into voluntary one-week team quarantine in a hotel. On game days, no more than 300 people are allowed in and around the stadium, ball boys have to wear gloves and are reduced to four. The balls have to be disinfected before and during the matches. TV reporters have to wear masks as well and keep a minimum of two meters distance from each other. Players on the bench also have to wear masks and need to keep a minimum of two meters distance from other players. Moreover, players were advised to keep distance when cheering after goals resulting in elbow bumps rather than hugs. The Austrian football association developed a concept that was very similar to the German one, allowing team training since 15 May 2020, after widespread coronavirus testing, and resumed play on 2 June 2020.

The COVID-19 outbreak led to initial chaos in the game plan of most international leagues. The different approaches of the different countries towards COVID-19 can be seen in the different agendas of the leagues. Despite that, almost all leagues were able to end the season 2019/20. After the major European leagues decided to continue playing, a committee of the UEFA started to plan the international competitions Euro League and Champions League. As a result, the winners of both competitions were determined in mini-tournaments with quarter-finals, semi-finals, and finally played as single-matches. The Champions League was held in Lisbon between August 12 and 23, and the Euro League was scheduled between August 10 and 21 in different German cities.

2. Theoretical background

2.1. Crisis and financial management in professional football clubs

PFCs are characterized by ongoing commercialization, having evolved from community-based sport organizations to major sport corporations (Calabuig et al., 2021). Despite the highly economical nature of professional football, it “continues to be a social business; economic in basis, but social in nature” (Morrow, 2013, p. 297). The evolution towards a business is considered as not congruent with the public reception of a football club as a community asset based on traditions and social value (Kennedy & Kennedy, 2012); a circumstance that entails an uncertainty also on the organizational ontology between being a business and being a community-based organization. The corporatization of a PFC can be seen above all in the legal form. The organizational structure of a PFC was an underemphasized research topic in sport management literature, and hence little was known about the predominant organizational concepts, ownership, and corporatization (Gammelsæter & Jakobsen, 2008). Within the last decade, researchers contributed a growing number of theoretical and empirical studies to the analysis of the market for football club investors (Ribeiro et al., 2019). Research increasingly explored the unique and widely varying corporate frameworks of PFCs. Rohde and Breuer (2017) analyzed the European football market for investors and found that incorporations of football clubs can be roughly divided into three groups: First, there is a small number of large clubs that generate significant revenues and hence can afford to remain fully member-owned. The most prominent member-owned clubs are Real Madrid or FC Barcelona, having a large fan base that constantly positions itself against the entry of (new) investors. Though these clubs are fully-member owned and therefore refer to a community sport organization, they are among the largest clubs in the world with high revenues and a large number of employees which leads to a structure similar to a corporation. Smaller member-owned clubs are advised to consider the entry of investors to remain nationally and internationally competitive. Second, few clubs have chosen the model of a public listed corporation. In the short-term, these clubs can generate a high amount of capital which also affects their sporting performance. However, being a publicly listed club does not tend to have long-term effects either on revenues or on international performance. Top clubs from the European league should consider going private again to be interesting for investors and therefore be able to collect additional resources. Third, which is also the major group and a kind of a standard, there are clubs with private investors. Private investors in football clubs are predominantly majority shareholders, giving them the ability not only to invest in a club but also to gain control over a club. An exception is the German Bundesliga and its 50+1 rule which limits the number of shares of private investors to a minority. Having a private majority investor is beneficial for team success and revenues, but leads also to a riskier investment strategy (Franck & Lang, 2014). In sum, one can conclude that there are only a few large and traditional clubs (e.g. FC Barcelona or Real Madrid) who can capitalize on their global brands and therefore stay being a fully member-owned club. All others are likely to have to increase their financial capacity with investors, whether through a public listing or a private investor, which entails a transformation from a community sport organization into a corporation.

The corporation of football clubs means that they think and act increasingly like companies. According to Moore and Levermore (2012), PFCs are highly comparable to small-to-medium sized enterprises (SMEs) in terms of employees, revenue, and organizational characteristics. However, the sport-related mission statement distinguishes football corporations from normal smaller businesses. PFCs reinvest profits or even take losses or debts to finance new players because football clubs are win maximizers rather than profit maximizers (Garcia-del-Barrio & Szymanski, 2009). The clubs spend as much as they can following the maxim of winning. As a result, they try to balance their budget and calculate with only a small profit. This makes them especially vulnerable to financial problems because unexpected and adverse shocks (e.g. injuries of important players, drop-out of important sponsors, relegation) promptly distress liquidity. This behavior is often described as irrational or even incompetent, yet it is only a response to the incentive scheme found in the sport system (Szymanski & Weimar, 2019). For example, the relegation into a lower league has huge influences on the revenues (Schreyer et al., 2018). Hence, it is rational that football clubs try to invest everything they have to prevent this sporting and financial misery. This starts kind of a rat race which pushes some clubs to overinvest beyond their financial limits and sometimes even into insolvency (Szymanski & Weimar, 2019). Adverse shocks, triggering financial distress in a football organization, can be all kinds of crises that affect football frequently and in several ways. In general, smaller organizations tend to suffer above average from crises due to a lack of resources, limited experience, and a lower formalization of crisis management planning (Doern, 2016; (Kraus et al., 2013). For these firms, it is also harder to assess the finance needed to address the stage of recovery (Lee et al., 2015), especially for a high-risk sector like football. In sum, it can therefore be said that PFCs are highly susceptible to crises because of their financial management, the uncertainty of their environment, and their size. Hence, there is a considerable need for permanent monitoring of both internal and external developments as well as crisis preparation of any football organization (Manoli, 2016).

2.2. Sport entrepreneurship and crises

The concept of sport entrepreneurship has been a progressively emerging research topic within the last few years (Escamilla-Fajardo et al., 2020; Huertas González-Serrano et al., 2020; Pellegrini et al., 2020). Though being a common vocabulary in sport management research, sport entrepreneurship still lacks a proper systematization, and several key concepts related to this field are open to interpretation and lack consensus (Bjärsholm, 2017; Hammerschmidt et al., 2020; Pellegrini et al., 2020).

It has been shown that organizations with an entrepreneurial profile can overperform during recessions followed by crises (Devece et al., 2016). In times of crisis, entrepreneurial organizations are more likely to survive and in the recovery phase, they show higher rates of growth, size, and job creation (Devece et al., 2016). Most researchers agree that entrepreneurial organizations are conceptualized as possessing the main characteristics being innovation, risk-taking, and proactiveness (Kreiser & Davis, 2010; Wales et al., 2020; Wiklund, 1999). Innovativeness is a very common business practice among SMEs (Kraus et al., 2012) and can improve business performance in a hostile environment of economic decline (Mendoza-Ramírez et al., 2016). Further, a proactive posture focused on creating innovative products or services will positively affect the operating results (Mendoza-Ramírez et al., 2016). Proactiveness is an “opportunity-seeking, forward-looking perspective involving introducing new products or services ahead of the competition and acting in anticipation of future demand to create change and shape the environment” (Lumpkin & Dess, 1996, p. 431). Proactive behavior is contrary to reactive behavior and in times of crisis, a mixture of these two can be essential for getting through a recession (Petzold et al., 2019). However, Brzozowski and Cucculelli (2016) have shown that the magnitude of a crisis related revenue reduction of companies is associated with the likelihood of reactive behavior, being especially apparent in the case of innovative investments.

For Jones et al. (2017), sport is a natural setting for entrepreneurial activities like seeking and capitalizing opportunities, which are viewed as key factors for success during recessions. Extant research suggests that the very nature of professional sport comprises several characteristics that support entrepreneurial behavior like ambition, commitment, or a hands-on mentality (Hemme et al., 2017). Ratten (2011) noted that sport organizations are highly proactive in managing their teams. Having an entrepreneurial lens is said to possess the potential of reducing the complexity of varying stakeholder perspectives in sport (Ratten & Ciletti, 2011) which can make it easier to focus on essential organizational activities during unstable and highly demanding times. Ball (2005) explains that having the mindset of an entrepreneur can increase economic efficiencies and hence save important resources for investments in the team. Recent research confirms the positive effects of entrepreneurial orientation on the sporting performance of football clubs and social performance (Hammerschmidt et al., 2020; Núñez-Pomar et al., 2020).

In this study, we define sport entrepreneurship as the emergence of entrepreneurial orientation and its subdimensions leading to entrepreneurial behavior in professional sport organizations. Evidence shows that sport entrepreneurship has become not only a strategic option for a club, but rather a managerial need to stay competitive in the hostile sport market (Legg & Gough, 2012; Ratten, 2010). As a result, one can conclude that it should also be relevant for coping with a crisis such as the COVID-19 pandemic.

3. Methodology

This empirical study is based on an exploratory multiple case study approach that aimed at understanding how PFCs from different countries are coping with COVID-19. As this topic reflects an infant research field, a case study approach was considered suitable (Gibbert et al., 2008). A case study “attempts to examine: (a) a contemporary phenomenon in its real-life context, especially when (b) the boundaries between phenomenon and context are not clearly evident” (Yin, 1981, p. 59). Yin (2009) further highlights the importance of clearly defining the case to be investigated. In the present study, the case of inquiry is an analysis of PFCs trying to tackle the current (business) environment caused by COVID-19.

3.1. Data collection and sample

Data was collected through interviews with CEOs of PFCs. They were considered suitable participants for the present study, as they dispose of the necessary knowledge on the topic under investigation. More precisely, semi-structured interviews were conducted as this mode of interviewing is flexible when it comes to the order of questioning and themes to be covered, still the discussion is centered upon the research topic, which is introduced by the interviewer (Klenke, 2008). An interview guide supported the execution of the interviews. Consequently, the number of focal themes were specified at the outset of the interviews. More precisely, the content of the interview guide focused on the effects on the club, acute actions of the PFC, and assumed long-term changes. Given the exploratory character of the present study, the procedure taken was not only related to a deductive approach, but included an inductive one as well. Thus, the prior framing of the field supported in coming close to the interviewees and their opinions and views but was open to adjustments and changes too.

The sampling method followed the underlying notion of purposive sampling (Easterby-Smith et al., 2012). The participants came from five different countries, namely Austria, Germany, Sweden, Switzerland, and the Netherlands. To be selected, they had to follow the criteria of being a professional club in a professional league in Europe. The CEOs were contacted by phone or email and invited to participate in a telephone interview. This resulted in ten interviews that were conducted in April 2020. As a homogeneous population was involved in the present study (Saunders & Townsend, 2018), ten interviews were considered to be an appropriate sample size.Table 2

Table 2.

Overview of the informants.

| Interviewee | League | League Level | Nr. of employees* |

|---|---|---|---|

| AUSTRIA | |||

| FC Admira Wacker Mödling | Bundesliga | 1 | 20 |

| LASK Linz | Bundesliga | 1 | 20 |

| SCR Altach | Bundesliga | 1 | 20 |

| TSV Hartberg | Bundesliga | 1 | 20 |

| GERMANY | |||

| 1. FSV Mainz | Bundesliga | 1 | 100 |

| SC Paderborn | Bundesliga | 1 | 80 |

| SpVgg Greuther Fürth | 2. Bundesliga | 2 | 60 |

| NETHERLANDS | |||

| AZ Alkmaar | Eredivise | 1 | - |

| SWEDEN | |||

| Mjällby AIF | Allsvenskan | 1 | 10 |

| SWITZERLAND | |||

| Grasshopper Club Zürich | Challenge League | 2 | 70 |

= without players

The interviews lasted between 20 and 45 minutes and were conducted in German (for the football clubs in Austria, Germany, and Switzerland) and English (for the clubs in Sweden and the Netherlands). All interviews were recorded, and in the next step transcribed and coded.

3.2. Execution of thematic analysis

As outlined above, the given study follows an exploratory approach. Hence, the used method should offer an accessible and theoretically-flexible approach to analyze qualitative data. Thematic analysis is a method for organizing and describing a data set, highlighting the most important themes that appear to be important for understanding and interpreting various aspects of the research topic (Fereday & Muir-Cochrane, 2006). The thematic analysis is appropriate for the present research because it is a rigorous method to create useful results in a complex surrounding (Nowell et al., 2017).

More precisely the analysis was conducted as follows. It started with the word for word transcription of the recorded interviews. This was accompanied by initial note-taking to document interesting statements to be remembered for the deeper analysis to come. Once this was done, interesting parts of each interview were coded in a systematic approach across the entire data set. Each data item has been given equal attention in the coding process and the data items were analyzed independently. Next, the codes were assorted into thematic groups. The topics were constantly refined and checked for internal homogeneity and external heterogeneity to ensure a coherent and meaningful analysis (Braun & Clarke, 2006). This was a two-stage process of revision and refinement. First, preliminary topics were examined at the level of encoded data items, with all transcription extracts read for each topic to provide a consistent model. If data items had no relation to the current topics, new topics were created. On the other hand, topics that were similar in content were summarized to enable the identification of overall themes. Second, after all the topics had been reviewed, an overview of the generated topics was applied, where the preliminary topics were examined in regard to the total data set to review if the provided analysis is competent enough to reflect the data holistically. This means that the remarks of a single interviewee could not lead to a topic. That is, the researcher often switched between the transcribed data set and the candidate topics, including any additional data that may have been omitted during the analysis process. As a result, the outcomes were subsumed under overarching themes, namely financial management, crisis management, stakeholder management, and solidarity and society.

All interviews were analyzed in the language in which they were conducted. When the process was completed, German parts were translated into English. The data was analyzed and interpreted by two researchers to provide a good balance between analytic descriptions and illustrative statements. Finally, the most relevant examples for answering the research aim were extracted and used for the scientific report of the analysis.

4. Findings

The interview findings suggest that the clubs were equally affected by the COVID-19 pandemic since all participating clubs play in leagues that have cancelled or postponed their matches. The league match schedules were dependent on the governmental measures and hence the timing in each league was slightly different (see Table 1). Despite these similarities, the findings of the interviews show that the clubs involved handled the crisis in different ways. The analysis of the interview data led to several key insights when respondents talked about their club's reaction to the COVID-19 pandemic, which formed the framework for the following presentation of results.

4.1. Financial management

Corona seems to have a great impact on the clubs’ liquidity as their main income streams are revenues from TV rights (up to 50% and more of their budget) and match days (merchandising, ticketing, hospitality, etc.). As mentioned above, football clubs try to balance their budget and only calculate with a small profit (Garcia-del-Barrio & Szymanski, 2009), hence the decrease of income challenges the clubs’ financial management. Even though the level of liquidity of the clubs varies, they are expected to be able to survive without playing until August 2020. Those clubs with revenues from the participation at international competitions were able to generate larger surpluses and at the time of the interview, they reported no financial problems. Interviewee 1 mentioned that the entire income from international competitions is profit because they have not taken these revenues into account when planning their budget. The interviewee also admitted that they were lucky with their sporting success. One interviewee of a German club reported that making surpluses and creating reserves are disadvantageous because these profits have to be taxed. Limited liquidity is inherent in professional football organizations and is especially apparent in times of the corona crisis, the following examples illustrate that:

Interviewee 4: “The club is economically affected [...] certain income is missing [...] because our budget is very limited, it is very difficult to build up reserves somewhere. And that's why it will be the normal case in the future that you calculate that you will have zero at the end of the season [...] we can only build reserves when there are unplanned earnings”

Interviewee 5, answering the question of how they are affected by the corona crisis: “The TV money is more than 50% of our budget and is now missing [...] nearly every income stream is now in danger [...] there are clubs who have already spent the TV revenues which they do not receive now [...] of course we have to be careful now, how can we secure liquidity?”

Interviewee 6, answering the question whether they are affected by the corona crisis: “We are of course also highly affected [...] we really want to finish the season, just to try to somehow get back to the normality of the income sources [...] have to keep playing to be able to exist”

Against the above-mentioned, it is not surprising, that only some of the clubs involved reported that they are actively engaged in building liquidity reserves. On that matter, the Swedish informant reported that football experts had started a debate in Sweden about regulatory actions that clubs must have 10% of their turnover available as liquid assets.

Most of the clubs (8 out of 10) responded to the decreased income and financial instability by introducing short-time work. With regards to costs, the largest item is player salaries. For example, interviewee 2 mentioned that “the highest costs incurred by a football club are naturally the personnel costs of the licensing department plus the trainer staff and administration and organization. The personnel costs account for about 70 percent of the total turnover”. Under the short-time working model, up to 50% of personnel costs can be saved due to substitutions by the state, and hence it was the most important action to decrease costs. Another interviewee stated that they even discussed with the players to reduce their salaries and bonuses beyond the governmental regulations. While a further interviewee reported on a possible measure to reduce costs by shutting down the stadium infrastructure.

Only two participants explicitly mentioned that they did a thorough cost analysis to detect saving potentials. To generate substituting revenues, some clubs take a proactive and innovative approach by offering tickets for a TV show (product) or a virtual game (donation).

4.2. Crisis management

As regards the approach to crisis management, almost every club (9 out of 10) was in a wait-and-see mode and made plans for different scenarios to be able to react. As mentioned in the theoretical foundations, reacting is the opposite of proactive behavior, which refers mainly to an acute action and less to planning. Hence, only one club showed proactive behavior and reported weekly scheduled forecasts and analyses, resulting in acute actions. In the following some examples are listed illustrating this approach:

Interviewee 4: “We will adapt [...]. At the bottom line, we have no other choice either”

Interviewee 5: “The most important thing is clarity. And when you have that, you can talk about the future, talk about action”

Interviewee 8: “We plan from day to day”

The overall findings suggest that PFCs neither have expertise in managing crises nor necessary structures for dealing with them. The findings further indicate that clubs with high surpluses because of revenues of international competition felt confident in having done a good job in the last year and plan to continue with it. Interviewee 9 stated that “toward the end of the season, even if we don't play a single game anymore, this club will make a profit”.

4.3. Stakeholder management

Another important source of income for a PFC is sponsorship and hospitality. An interviewee from Austria reported that 45% of their income is generated through sponsorship and hospitality. Since the clubs are not playing, they cannot provide the sponsorship service. Interviewee 6 reported, that “we have a few who are terminating their sponsorship contracts due to non-fulfillment because there are no games and they don't get their advertising services”. However, most of the stakeholders (sponsors, fans, etc.) waive repayments. Another club expects a loss of sponsorship of about 10%, suggesting that this is not because the sponsors don't want to be active but because they financially suffer from the crisis as well.

To avoid repayments, some clubs have started offering their sponsors and fans a form of compensation through increased social media appearance, extra advertising time in the next season, or merchandising products from the fan shop. An initiative from one participant from the Austrian Bundesliga is to offer their fans a place on a match jersey if they waive the repayment of their season ticket.

With regards to external communication, the findings indicated that only a few clubs have an intensive exchange with their stakeholders. For example, interviewee 10 sends weekly newsletters to their sponsors, while some other interviewees reported an emotional bond with their sponsors, and have contacted each sponsor personally to get through the time together.

The main sponsor of interviewee 2 is a sport betting company, so it is also active in the same industry as the club. This means that when the sport industry is in crisis, not only the club but also the main sponsor is affected. Other clubs involved in the study have main sponsors which are not endangered because they are either financially very potent or active in crisis-proof sectors, like baby nutrition.

Interviewee 1: “All sponsors without exception do not want their money back, even if the league is cancelled”

Interviewee 9: “We try to stay connected with our stakeholders”

Interviewee 10: “A lot of companies have hard times now and the first thing they cut off is sponsorship costs”

4.4. Solidarity and the social role of PFCs

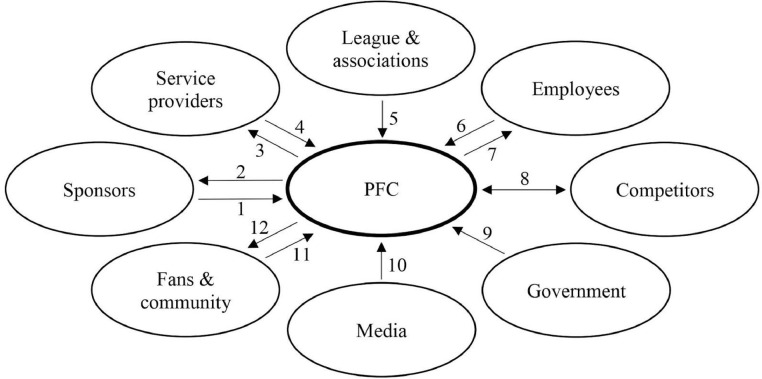

All clubs reported an enormously high level of solidarity, which appeared in many different directions. Fig. 1 represents an overview of all streams of solidarity found in this study, whereas each stream is represented by a numbered arrow.

Fig. 1.

Streams of solidarity.

Nearly every club reported great support from their sponsors (Stream 1). Interviewee 1 mentioned that all of their sponsors guaranteed their contractually determining payments, even when the season will be canceled. While Interviewee 2 reported, “it is the goal to ideally not return any funds”.

Most of the sponsors show readiness to help the clubs by, for example, accepting compensation through social media presence or more advertising time next season and hence pay out the full amount of the sponsorship funds. The club of Interviewee 9 showed high solidarity to his sponsors by paying back sponsorship money to sponsors and service providers that are in financial need because of the economic impact of the crisis (Stream 2 and 3). Vice versa, there are service providers who are open to discussions about deferring payments (Stream 4). Leagues and international associations supported clubs with a lot of flexibility regarding match schedules, rules for club insolvency, and creating possibilities to extend player contracts throughout the summer (Stream 5). However, interviewees 2, 3, 8, and 9 mentioned a lack of action from the major associations UEFA and FIFA, above all financially.

On that issue, Interviewee 2 mentioned “we all know they are rich”.

In financial terms, short-time working was the most important measure and is based on a voluntary commitment to forego salary by the highly solidary employees (Stream 6). A German club reported that players waive part of their salary and give it to club employees so that they can continue to receive their full net salary (Stream 7). The wealthy clubs involved in the study stated that they forego state aid and pay their employees in full, even though they hardly work at all. In Austria, Sweden, and the Netherlands, the Interviewees reported a high level of solidarity between the clubs (Stream 8), Interviewee 3 summarized it as “the crisis unites”.

In Sweden, the clubs have frequent league meetings and share best practices and ideas about how to cope with the crisis. The highest level of solidarity between clubs seems to be apparent in Germany where the FC Bayern München, Borussia Dortmund, RB Leipzig, and Bayer Leverkusen created a €20 million solidarity fund to help German clubs of the top two tiers to avoid a potential financial crisis during the pandemic. The interviewees also reported that they receive support from states or stakeholders (Stream 9). In Sweden, sport is backed by the state with an aid package amounting to 50 million euros. Professional sport in Switzerland was supported with €50 million and the possibility to receive a loan from the government. The TV broadcaster Sky Germany supported the German football clubs by paying TV money in advance, which is normally paid out after the respective quarter (Stream 10). The findings suggest that there is strong solidarity between the PFCs and their fans (Stream 11 and 12). It has been reported that the fans of the participating clubs were consistently willing to waive the repayment of their season tickets. One club from Austria organized a game without opponents, a fictive game, and the fans bought tickets, virtual snacks, and virtual drinks to support their club.

Additionally, the clubs involved in the study have shown great solidarity with society as a whole. The GC Zürich, and its employees, for example, created a fund to financially support people from Zürich who are suffering due to the crisis. Season ticket holders of a German club waived their right of refund and the generated money was partially distributed to regional amateur football clubs to support them. Other interviewees reported that they have teamed up with their fan club to help the elderly or provide free drinks to hospital employees. Interviewee 1 explained that when their employees have time left over, they do a telephone service for the regional Red Cross. Every club offered their fans a full or partial refund for their season ticket. As mentioned above, clubs tried to avoid monetary refunds and offered compensations, for example, by merchandising products from the fan shop. As many fans want to support their club and they waive compensation offerings or refunds. Interviewee 6 believes “with solidarity, you can overcome any crisis”.

Furthermore, the findings suggest that there are cultural differences. Non-German clubs emphasized the importance of football's role model function for society. Interviewee 10, for example, mentioned “the clubs are very important for the whole Swedish society”. More critically, Interviewee 1 meant that “you ask everyone to stay at home and the superstars don't. This is a disaster for me! It's the same thing when I send people to a training facility. I tell everyone that you should stay at home, but we are training again. This is extremely counterproductive for me at a time like this and I can't understand it”. German clubs, on the contrary, emphasized the economical relevance of professional football stating the wish to be perceived as an industry and treated accordingly. For example, interviewee 6 explains that at the time of the interview, their club was not allowed to train, since their training court counts legally as a public sport ground and not a business facility. Simultaneously, business facilities and factories were open. This interviewee added: “Football is no fun event. Football should be treated like any other business”. In a similar vein, Interviewee 7 mentioned that “football is described as a 'fun event' although in Germany 60 000 jobs are involved”.

German clubs criticize the reduction of football to “22 field players who earn millions” (Interviewee 7) and emphasize the offered added value of football to society, also outside of the pitch. In addition, Interviewee 6 mentioned, football is not only about the players, “but also about the one who does the ticketing, sells the snacks or takes care of the fan projects for 2000 Euro gross”. Interviewee 6 added: “We know of course that football is always associated with the millionaires, who people just like to see and say yes, they have money, and they don't need it, they have to give something away”.

4.5. Change management

The overall findings suggest that the clubs believe in a short-term levelling down of the market which means that transfer expenses will decrease. However, they also believe that the market will recover in 2-3 years because clubs will continue to spend the funds that will be available to them. Interviewee 7 described it as: “Humans forget quickly”. Interviewee 10 believes in a “wake-up call” for many clubs that will allow them to plan their finances more conservatively to survive future crises. Another assumption is that football may become more down-to-earth again, which explained Interviewee 7 as follows: “Does it have to be a 5 star plus hotel every time, or is 4 stars, not enough?”. Two clubs that were financially strong during the time of research and emphasize that they want to continue as before, although being aware that the world of values may change. As interviewee 1 said: “We are very satisfied [...]. The structure is ok, the financial development, the economic development is ok and as I said, great luck that we had this year [...] is the sporting success in the Europa League”.

In general, the interview participants show a low level of opportunity seeking. Interviewee 3 states that “every crisis is a challenge, an opportunity”, but cannot name any particular opportunity he has recognized. Interviewee 9 added that “it doesn't feel right to talk about chances when people are dying left and right”.

Further, interviewee 9 suggests that large clubs, in particular, will benefit from the crisis: “Usually in any financial crisis, the strong get stronger and the weak get weaker [...] if you are in a healthy position, you might benefit from this in the long run”. Three clubs see the crisis as an opportunity for their young players, who are cheaper and may get more chances in times of limited budgets. Interviewee 1 explains that “we have a cooperation club that plays in the second league [...] there are many talents that don't cost so much money but still perform well. I think that almost all clubs will have to count every euro in the contract negotiations in the future. The transfer fees will decrease and it will take 2-3 seasons until they are back to the level of before”. Most interviewees seem to agree that the COVID-19 crisis will accidentally change the football business due to its already highly apparent impact. However, they find it difficult to imagine or predict distinct changes at present.

5. Discussion

Our study is the first empirical work in the field of organizational management providing insights about the coping behavior of ten European professional football clubs with the ongoing COVID-19 pandemic. The findings contribute to current literature in various ways.

5.1. Financial management

The research has shown that the biggest problem during the Corona crisis is the liquidity of the clubs. In general, our study supports the statement of Garcia-del-Barrio and Szymanski (2009) that PFCs try to maximize winning rather than profit. The organizational goals of maximizing sporting performance lead to a very tight budget with only small profits (Garcia-del-Barrio & Szymanski, 2009) which was confirmed by the CEOs of the clubs in the interviews. The interviewees also acknowledged that some of the clubs would not survive the corona crisis for long, as the pandemic had left them with no income, confirming the vulnerability of professional football in crises (Manoli, 2016). Our findings further emphasize that football organizations are frequently affected by unexpected adverse shocks (Szymanski & Weimar, 2019) which let us conclude that they are either unaware of the particular vulnerability of the industry or ignore it on purpose to remain competitive and thus simply hope for the best. Our results support the findings of Manoli (2016) that PFCs need a considerable amount of permanent monitoring of both internal and external developments as well as crisis preparation. However, our interview findings revealed that none of the participating clubs has adequate crisis management structures. Moreover, most of the CEOs stated that they are in a wait-and-see position and rather react to new circumstances than approaching the situation proactively through systematic behavior and planning. These results show that the process of crisis management is severely neglected in PFCs and they are therefore not prepared for a crisis.

The corona crisis has sparked conversations about the financial management of PFCs and one interviewee from a Swedish club mentioned that for this reason, the football industry and policymakers in Sweden are now talking about the requirement that clubs must have 10% of their income available as liquid assets. Based on the findings, this seems to be a reasonable and practicable solution, because, on the one hand, it considers the financial possibilities of each professional club, whether the first or second league, and on the other hand it affects all clubs at the same time equally. However, this may impact the expenses for players of all Swedish clubs for one year and therefore their performance in international competition could suffer. An even more practical way would be if the UEFA would integrate such a liquidity rule into the already existing Financial Fair Play regulations, established to improve the overall financial health of football (Müller et al., 2012).

Not surprisingly, and in line with previous research, the findings of this study show that financially potent clubs are less concerned about COVID-19 and its possible consequences. Our study indicates that clubs that have outperformed expectations in international competitions can make profits even in times of crisis. However, it might be questioned if this results rather from sporting luck than from good planning.

5.2. Stakeholder relations

Based on the findings it can be concluded that managing stakeholder relations should play an even stronger role in times of crisis. Concerning the selection of stakeholders from the outset and where it is possible, the findings point out that it is advisable to choose sponsors who are active in industries that are more crisis-resistant, as a recession in sport then does not affect sponsors in the same way. Since sponsorship is one of the main streams of income for PFCs, we have also seen that clubs should not only focus on sponsors from a crisis-proof sector but should also look for financially potent sponsors who can increase the probability of continued support even in times of crisis. In addition, our results show that the clubs in the COVID-19 crisis benefited from the fact that their main sponsors were active in general crisis resistant sectors such as the food, pharmaceutical, or telecommunications industry. However, COVID-19 pandemic has caused widespread and significant economic consequences for companies in several industries (Baker et al., 2020). Many sponsors of the participants suffered from the current downturn and interviewees reported that they expect a sponsorship loss, not because the sponsors don't want to but primarily because they are financially not able to. Some interviewees reported a strong emotional bond with their sponsors, resulting in high levels of loyalty and support regardless of the current situation. Hence, our findings support previous research (McDonald et al., 2010), that maintaining stakeholder loyalty is paramount in times of crisis.

Further, the statements of the club CEOs indicate that stakeholders have different perceptions of a PFC as a corporation and of football as an economic sector. Within the last decades, PFCs have evolved into large commercial enterprises (Ribeiro et al., 2019; Szymanski & Weimar, 2019), but are still basically perceived and treated by the public as community-based sport organizations. Larger clubs in particular showed a desire to change this perception and emphasized football as an important economic sector. The commercialization and corporation of PFCs mean that they think and act increasingly like companies. In addition, the professional football sector has not only a major social but also economic impact (Szymanski & Weimar, 2019). These are facts that are well-accepted in research but not in public.

Our study also revealed remarkable levels of solidarity between the PFC and external stakeholders facing the crisis. The COVID-19 pandemic was enormous financial distress for PFCs. Their income collapsed and liquidity was limited to such an extent, that almost every club was or is threatened in its existence. The investigation clearly shows that this situation thus created a sense of commitment to support each other in solidarity. The findings suggest that the highest solidarity was found between the PFCs and their fans. Fans are prepared to waive repayments for season tickets or buy tickets for fictional games. The study has shown that the fans not only support their teams at the stadium with their cheers but also show strong solidarity in times of crisis. Additionally, there appears to be reciprocity between these two actors. Some employees of the Swiss club Grasshoppers Zürich created funds to support fans who were suffering from the corona crisis. The findings obtained seem to be in line with previous research showing that the relationship between fans and PFCs is characterized by a strong emotional bond (e.g. Katz & Heere, 2016). In addition to this expected relationship, the interviews revealed that also other stakeholders showed strong solidarity. One would assume that this is a matter of economic thinking because, for example, a stakeholder does not want to lose a good customer or employees want to support their club to not lose their job. However, our interviews reveal that there is a network of support with stakeholders (Fig. 1) who show a high degree of solidarity based on how emotionally attached they are to the club and are therefore intrinsically motivated to support their club and overcome this crisis together, even if it seems irrational.

5.3. Sport entrepreneurship

The literature review indicates that sport entrepreneurship is an elementary management strategy for PFCs and has the potential to be a relevant instrument to cope with the COVID-19 crisis. Entrepreneurial activities, such as capitalizing opportunities by entering new or existing markets with new or existing goods and services, are referred to organization's entrepreneurial orientation (EO), which is expressed by the combination of the three dimensions innovation, pro-activeness, and risk-taking (Wiklund, 1999; Wiklund & Shepherd, 2003). Recent literature emphasized the opportunity of organizations with an entrepreneurial profile to overperform during times of economic decline (Brzozowski & Cucculelli, 2016; Devece et al., 2016; Petzold et al., 2019). The findings have shown that some clubs have chosen innovative approaches to counteract the reduction in income by introducing new products or services to their fans.

The findings, however, also showed that PFCs tend to be rather reactive in times of crises and adapt to new circumstances because they have to and not because of an entrepreneurial mindset of the PFCs’ management. An entrepreneurial mindset was not evident in this study. That is, we assume that a high revenue reduction fosters the likelihood of non-proactive behavior of football CEOs.

6. Conclusion

In this article, we investigated the responses of European professional football clubs to the COVID-19 pandemic during the season 2019/20. The COVID-19 pandemic represents a new type and quality of challenge for sport organizations. Ten semi-structured interviews with CEOs of PFCs from Austria, Germany, Netherlands, Sweden, and Switzerland provided in-depth insights about how the football sector copes with the corona crisis. More precisely, this paper sheds light on strategic responses concerning financial management, stakeholder relations, and the importance of sport entrepreneurship in times of crisis.

6.1. Practical implications

Our qualitative investigation revealed that the corona crisis caused existence-threatening liquidity issues and stressed the financial management of many PFCs. Professional sport organizations calculate in general only small profits and the sector is highly vulnerable to crises, a combination that makes professional football unstable and fragile. Unexpected adverse shocks that lead to a revenue reduction, like the COVID-19 pandemic, have the potential to financially collapse the industry, emphasized by our interview participants who reported that without playing most of the clubs would not have survived longer than until August. The findings of our study revealed that PFCs have hardly established any crisis management structures and we suggest that PFCs engage in developing internal expertise on how to deal with a crisis.

Sponsors are one of the major stakeholders of PFCs. To diversify the financial risk of a club, our interviews highlighted that it might be beneficial to have a main sponsor from an industry whose economy is not cyclical with sport or, even better, from a crisis resistant sector. Further, PFCs should invest in the relationships with sponsors because an emotional bond will enhance loyalty and therefore increase the chance of getting support in times of recessions. The media echo during the COVID-19 pandemic exposed that the public still perceives PFCs as community-based sport organizations and that their economical relevance is neglected. We reinforce the call of our interview participants to perceive and treat PFCs more as a company. However, one should bear in mind that although PFCs are highly commercialized, they are still social in nature. This was made particularly clear by the COVID-19 crisis and the various streams of high solidarity between the PFC and its stakeholders, leading to mutual support and a sense of unity to overcome the downturn.

In terms of entrepreneurial orientation of PFCs, our study shows that the revenue reduction due to the COVID-19 pandemic increases the likelihood of reactive behavior and decreased proactivity. However, PFCs are well advised to engage in sport entrepreneurship since the findings indicate that an entrepreneurial profile is a paramount factor for surviving during and after a crisis. Our overall findings suggest that PFCs are well advised to use the sport's inherent potential for entrepreneurship (e.g., Ferreira et al., 2019) in periods of recession since it may be an important factor when it comes to organizational performance in times of economic downturns.

6.2. Limitations and future research

In the context of this study, we qualitatively examined ten PFCs from a total of five countries. The study design was carefully selected to increase the likelihood of analytical generalization. The study represents an urgent first step that will hopefully trigger future studies examining the impacts of crises in sport, but it remains an exploratory study that offers only preliminary results. The study design limited the sample size to professional clubs from European countries and hence limited the generalizability of the findings.

Despite these limitations, we consider this exploratory investigation to be an important early contribution to research on the management of sport organizations in general and in the realm of an external crisis such as the COVID-19 pandemic in particular. Therefore, a number of promising future research avenues are ahead. The interviewees assume that the crisis is causing a significant yet unintended change in the football business. Future research should focus on the impact of COVID-19 on both the financial and non-financial performance of PFCs. The same refers to the impact of the measures initiated. Our study can only provide tentative results and calls for more rigorous research on the consequences of the coping measures and actions identified. The study of long-term effects, followed up with longitudinal analyses to investigate strategic responses of PFCs to the corona crisis will have to be the goal of future research. More research is also needed on crisis management in sport organizations, the findings indicated a serious lack of expertise and understanding concerning this relevant business function.

Finally, we also encourage researchers to examine the effects of the COVID-19 crisis and responses of professional and non-professional sport organizations in other countries and regions to achieve a global and more comprehensive understanding.

Acknowledgment

This work was supported by the Open Access Publishing Fund provided by the Free University of Bozen-Bolzano.

Biographies

Jonas Hammerschmidt is a doctoral student at the School of Business and Management of Lappeenranta-Lahti University of Technology (LUT), Finland, undertaking research in the field of sport entrepreneurship and innovation. He holds a Bachelor’s degree in Sport Management from the German Sports University Cologne and a Master’s in Entrepreneurship from the University of Liechtenstein.

Susanne Durst is Full Professor of Management at Tallinn University of Technology, Estonia, and Full Professor of Business Administration at the University of Skövde, Sweden. She holds a doctorate in Economics from Paris-Sud University, France. Her research interests include small business management, knowledge (risk) management, responsible digitalization, and sustainable business development.

Sascha Kraus is Full Professor of Management at the Free University of Bozen-Bolzano, Italy. He holds a doctorate in Social and Economic Sciences from Klagenfurt University, Austria, a Ph.D. in Industrial Engineering and Management from Helsinki University of Technology and a Habilitation (Venia Docendi) from Lappeenranta University of Technology, both in Finland. Before, he held Full Professor positions at Utrecht University, The Netherlands, the University of Liechtenstein, École Supérieure du Commerce Extérieur Paris, France, and at Durham University, United Kingdom. He also held Visiting Professor positions at Copenhagen Business School, Denmark and at the University of St. Gallen, Switzerland.

Kaisu Puumalainen is Full Professor in Technology Research in the School of Business and Management at Lappeenranta-Lahti University of Technolog (LUT), Finland. Her primary areas of research interest are innovation, entrepreneurship, sustainability, strategic orientations and internationalization.

References

- Anderson R.M., Heesterbeek H., Klinkenberg D., Hollingsworth T.D. How will country-based mitigation measures influence the course of the COVID-19 epidemic? The Lancet. 2020;395(10228):931–934. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(20)30567-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baker, S. R., Bloom, N., Davis, S. J., Kost, K., Sammon, M., &Viratyosin, T. (2020). The unprecedented stock market reaction to COVID-19. The Review of Asset Pricing Studies.

- Baldwin R. Keeping the lights on: Economic medicine for a medical shock. Macroeconomics. 2020;20:20. [Google Scholar]

- Ball S. Hospitality, Leisure. Sport and Tourism Network; 2005. The importance of entrepreneurship to hospitality, leisure, sport and tourism; p. 15. [Google Scholar]

- Bjärsholm D. Sport and social entrepreneurship: A review of a concept in progress. J. Sport Manage. 2017;31(2):191–206. [Google Scholar]

- Braun V., Clarke V. Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qual. Res. Psychol. 2006;3(2):77–101. [Google Scholar]

- Breier M., Kallmuenzer A., Clauss T., Gast J., Kraus S. The role of business model innovation in the hospitality industry during the COVID-19 crisis. International Journal of Hospitality Management. 2021;92:102723. doi: 10.1016/j.ijhm.2020.102723. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brzozowski J., Cucculelli M. Proactive and reactive attitude to crisis: Evidence from European firms. Entrepreneur. Busi. Econ. Rev. 2016;4(1):181–191. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, J., Wang, X., Zhang, S., Liu, B., Wu, X., Wang, Y., Wang, X., Yang, M., Sun, J., &Xie, Y. (2020). Findings of acute pulmonary embolism in COVID-19 patients. Available at SSRN 3548771.

- Calabuig F., Prado-Gascó V., Núñez-Pomar J., Crespo-Hervás J. The role of the brand in perceived service performance: Moderating effects and configurational approach in professional football. Technological Forecasting and Social Change. 2021;165:120537. [Google Scholar]

- Clark C., Davila A., Regis M., Kraus S. Predictors of COVID-19 voluntary compliance behaviors: An international investigation. Global Trans. 2020;2:76–82. doi: 10.1016/j.glt.2020.06.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Corsini, A., Bisciotti, G. N., Eirale, C., &Volpi, P. (2020). Football cannot restart soon during the COVID-19 emergency! A critical perspective from the Italian experience and a call for action. Br. J. Sports Med., bjsports-2020-102306. [DOI] [PubMed]

- Devece C., Peris-Ortiz M., Rueda-Armengot C. Entrepreneurship during economic crisis: Success factors and paths to failure. J. Busi. Res. 2016;69(11):5366–5370. [Google Scholar]

- Doern R. Entrepreneurship and crisis management: The experiences of small businesses during the London 2011 riots. Int. Small Busi. J. 2016;34(3):276–302. [Google Scholar]

- Easterby-Smith M., Thorpe R., Jackson P.R. Sage; 2012. Management research. [Google Scholar]

- Escamilla-Fajardo P., Núñez-Pomar J.M., Ratten V., Crespo J. Entrepreneurship and innovation in soccer: Web of science bibliometric analysis. Sustainability. 2020;12(11):4499. [Google Scholar]

- Fereday J., Muir-Cochrane E. Demonstrating rigor using thematic analysis: A hybrid approach of inductive and deductive coding and theme development. Int. J. Qual. Methods. 2006;5(1):80–92. [Google Scholar]

- Ferreira J.J.M., Fernandes C.I., Kraus S. Entrepreneurship research: mapping intellectual structures and research trends. Rev. Manag. Sci. 2019;13:181–205. [Google Scholar]

- Franck E., Lang M. A theoretical analysis of the influence of money injections on risk taking in football clubs. Scottish J. Pol. Econ. 2014;61(4):430–454. [Google Scholar]

- Gammelsæter H., Jakobsen S.-E. Models of organization in Norwegian professional soccer. European Sport Manage. Quart. 2008;8(1):1–25. [Google Scholar]

- Garcia-del-Barrio P., Szymanski S. Goal! Profit maximization versus win maximization in soccer. Rev. Indust. Org. 2009;34(1):45–68. [Google Scholar]

- Gibbert M., Ruigrok W., Wicki B. What passes as a rigorous case study? Strat. Manage. J. 2008;29(13):1465–1474. [Google Scholar]

- Hammerschmidt J., Eggers F., Kraus S., Jones P., Filser M. Entrepreneurial orientation in sports entrepreneurship—A mixed methods analysis of professional soccer clubs in the German-speaking countries. Int. Entrepreneur. Manage. J. 2020;16(3):839–857. [Google Scholar]

- Hemme F., Morais D.G., Bowers M.T., Todd J.S. Extending sport-based entrepreneurship theory through phenomenological inquiry. Sport Manage. Rev. 2017;20(1):92–104. [Google Scholar]

- HuertasGonzález-Serrano, M., Jones, P., &Llanos-Contrera, O. (2020). An overview of sport entrepreneurship field: A bibliometric analysis of the articles published in the Web of Science. Sport in Society, 23(2), 296–314.

- Jones P., Jones A., Williams-Burnett N., Ratten V. Let’s get physical: Stories of entrepreneurial activity from sports coaches/instructors. Int. J. Entrepreneur. Innov. 2017;18(4):219–230. [Google Scholar]

- Katz M., Heere B. New team, new fans: A longitudinal examination of team identification as a driver of university identification. J. Sport Manage. 2016;30(2):135–148. [Google Scholar]

- Kennedy P., Kennedy D. Football supporters and the commercialisation of football: Comparative responses across. Europe. Soccer & Society. 2012;13(3):327–340. [Google Scholar]

- Khafaie M.A., Rahim F. Cross-country comparison of case fatality rates of COVID-19/SARS-COV-2. Osong Public Health and Res. Perspect. 2020;11(2):74–80. doi: 10.24171/j.phrp.2020.11.2.03. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Klenke K. Emerald group publishing; 2008. Qualitative research in the study of leadership. [Google Scholar]

- Kraus S., Clauss T., Breier M., Gast J., Zardini A., Tiberius V. The economics of COVID-19: Initial empirical evidence on how family firms in five European countries cope with the corona crisis. Int. J. Entrepreneur. Behav. Res. 2020;26(5):1067–1092. [Google Scholar]

- Kraus S., Moog P., Schlepphorst S., Raich M. Crisis and turnaround management in SMEs: a qualitative-empirical investigation of 30 companies. International Journal of Entrepreneurial Venturing. 2013;5(4):406–430. [Google Scholar]

- Kraus S., Rigtering J.P.C., Hughes M., Hosman V. Entrepreneurial orientation and the business performance of SMEs: A quantitative study from the Netherlands. Rev. Manager. Sci. 2012;6(2):161–182. [Google Scholar]

- Kreiser P.M., Davis J. Entrepreneurial orientation and firm performance: The unique impact of innovativeness, proactiveness, and risk-taking. J. Small Busi. Entrepreneur. 2010;23(1):39–51. [Google Scholar]

- Lee N., Sameen H., Cowling M. Access to finance for innovative SMEs since the financial crisis. Research Policy. 2015;44(2):370–380. [Google Scholar]

- Legg D., Gough V. Calgary Flames: A case study in an entrepreneurial sport franchise. Int. J. Entrepreneur. Ventur. 2012;4(1):32. [Google Scholar]

- Lumpkin G.T., Dess G.G. Clarifying the entrepreneurial orientation construct and linking it to performance. Acad. Manage. Rev. 1996;21(1):135. [Google Scholar]

- Manoli A.E. Crisis-communications management in football clubs. Int. J. Sport Commun. 2016;9(3):340–363. [Google Scholar]

- McDonald L.M., Sparks B., Glendon A.I. Stakeholder reactions to company crisis communication and causes. Public Relat. Rev. 2010;36(3):263–271. [Google Scholar]

- McKibbin, W. J., &Fernando, R. (2020). The global macroeconomic impacts of COVID-19: Seven scenarios. CAMA Working Paper, No. 19/2020.

- Mendoza-Ramírez L., Toledo-López A., Arieta-Melgarejo P. The contingent effect of entrepreneurial orientation on small business performance in hostile environments. Ciencias Administrativas. Teoría y Praxis. 2016;12(1) [Google Scholar]

- Moore N., Levermore R. English professional football clubs: Can business parameters of small and medium-sized enterprises be applied? Sport, Busi. Manage. Int. J. 2012;2(3):196–209. [Google Scholar]

- Morrow S. Football club financial reporting: Time for a new model? Sport, Busi. Manage. Int. J. 2013;3(4):297–311. [Google Scholar]

- Müller J.C., Lammert J., Hovemann G. The financial fair play regulations of UEFA: An adequate concept to ensure the long-term viability and sustainability of European club football? Int. J. Sport Finance. 2012;7(2) [Google Scholar]

- Nowell L.S., Norris J.M., White D.E., Moules N.J. Thematic analysis: Striving to meet the trustworthiness criteria. Int. J. Qual. Methods. 2017;16(1) 160940691773384. [Google Scholar]

- Núñez-Pomar, J. M., Escamilla-Fajardo, P., &Prado-Gascó, V. (2020). Relationship between entrepreneurial orientation and social performance in Spanish sports clubs. The effect of the type of funding and the level of competition. Int. Entrepreneur. Manage. J.. 10.1007/s11365-020-00660-3.

- Parnell, D., Widdop, P., Bond, A., &Wilson, R. (2020). COVID-19, networks and sport. Managing Sport and Leisure, 1–7. 10.1080/23750472.2020.1750100.

- Pellegrini, M. M., Rialti, R., Marzi, G., &Caputo, A. (2020). Sport entrepreneurship: A synthesis of existing literature and future perspectives. Int. Entrepreneur. Manage. J.. 10.1007/s11365-020-00650-5.

- Petzold S., Barbat V., Pons F., Zins M. Impact of responsive and proactive market orientation on SME performance: The moderating role of economic crisis perception. Canadian J. Admin. Sci. 2019;36(4):459–472. [Google Scholar]

- Ratten V., Ciletti D. The entrepreneurial nature of sports marketing: Towards a future research agenda. Int. J. Sport Manage. Market. 2011;7(1/2):1–143. [Google Scholar]

- Ratten Vanessa. Developing a theory of sport-based entrepreneurship. J. Manage. Org. 2010;16(4):557–565. [Google Scholar]

- Ratten Vanessa. Sport-based entrepreneurship: Towards a new theory of entrepreneurship and sport management. Int. Entrepreneur. Manage. J. 2011;7(1):57–69. [Google Scholar]

- Ribeiro J., Branco M.C., Ribeiro J.A. The corporatisation of football and CSR reporting by professional football clubs in Europe. Int. J. Sports Market. Sponsor. 2019;20(2):242–257. [Google Scholar]

- Rohde M., Breuer C. The market for football club investors: A review of theory and empirical evidence from professional European football. European Sport Manage. Quart. 2017;17(3):265–289. [Google Scholar]

- Saunders M.N.K., Townsend K. In: The SAGE Handbook of Qualitative Business and Management Research Methods: History and Traditions. Cassell C., Cunliffe A., Grandy G., editors. SAGE Publications Ltd; 2018. Choosing Participants; pp. 480–492. [Google Scholar]

- Schreyer, Torgler B., Schmidt S.L. Game outcome uncertainty and television audience demand: New evidence from German football. German Econ. Rev. 2018;19(2):140–161. [Google Scholar]

- Sharma, S., Singh, G., Sharma, R., Jones, P., Kraus, S., &Dwivedi, Y. K. (2020). Digital health innovation: exploring adoption of COVID-19 digital contact tracing apps. IEEE Trans. Eng. Manage.; DOI: 10.1109/TEM.2020.3019033.

- Sharma S, Singh G., Sharma R., Jones P., Kraus S., Dwivedi Y.K. Digital health innovation: exploring adoption of COVID-19 digital contact tracing apps. IEEE Transactions on Engineering Management. 2020 doi: 10.1109/TEM.2020.3019033. In press. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Singhal T. A review of coronavirus disease-2019 (COVID-19) Indian J. Pediatrics. 2020;87(4):281–286. doi: 10.1007/s12098-020-03263-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Szymanski S., Weimar D. Insolvencies in professional football: A German sonderweg? Int. J. Sport Finance. 2019;14(1):54–68. [Google Scholar]

- Tian, H., Liu, Y., Li, Y., Wu, C.-H., Chen, B., Kraemer, M. U. G., Li, B., Cai, J., Xu, B., Yang, Q., Wang, B., Yang, P., Cui, Y., Song, Y., Zheng, P., Wang, Q., Bjornstad, O. N., Yang, R., Grenfell, B., … Dye, C. (2020). The impact of transmission control measures during the first 50 days of the COVID-19 epidemic in China [Preprint]. Infectious Diseases (except HIV/AIDS). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Wales, W. J., Kraus, S., Filser, M., Stöckmann, C., &Covin, J. G. (2020). The status quo of research on entrepreneurial orientation: Conversational landmarks and theoretical scaffolding. J. Busi. Res..

- WHO . World Health Organization; 2020. Coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19): Situation report; p. 109. [Google Scholar]

- Wiklund J. The sustainability of the entrepreneurial orientation—Performance relationship. Entrepreneurship Theory and Practice. 1999;24(1):37–48. [Google Scholar]

- Wiklund J., Shepherd D. Knowledge-based resources, entrepreneurial orientation, and the performance of small and medium-sized businesses. Strat. Manage. J. 2003;24(13) [Google Scholar]

- Yin R.K. The case study crisis: Some answers. Admin. Sci. Quart. 1981;26(1):58. [Google Scholar]

- Yin R.K. Sage Publications; 2009. Case study research: Design and methods. [Google Scholar]