Abstract

Objectives

The aim of the present study was to evaluate the clinical performance of four SARS-CoV-2 immunoassays and their contribution in routine care for the diagnosis of COVID-19, in order to benefit of robust data before their extensive use.

Methods

The clinical performance of Euroimmun ELISA SARS-CoV-2 IgG, Abbott SARS-CoV-2 IgG, Wantai SARS-CoV-2 Ab ELISA, and DiaPro COVID-19 IgG confirmation were evaluated in the context of both a retrospective and a prospective analysis of COVID-19 patients. The retrospective analysis included plasma samples from 63 COVID-19 patients and 89 control (pre-pandemic) patients. The prospective study included 203 patients who tested either negative (n = 181) or positive (n = 22) by RT-PCR before serology sampling.

Results

The specificity was 92.1 %, 98.9 %, 100 % and 98.9 % and the sensitivity 14 days after onset of symptoms was 95.6 %, 95.6 %, 97.8 % and 95.6 % for Euroimmun IgG, Abbott IgG, Wantai Ab, and DiaPro IgG confirmation SARS-CoV-2 immunoassays, respectively. The low specificity of Euroimmun IgG (for ratio <5) was not confirmed in routine care setting (98.5 % negative agreement). Serology was complementary to RT-PCR in routine care and lead to identification of false positive (Ct>38, <2 targets detected) and false negative RT-PCR results (>1 month post onset of symptoms).

Conclusions

Serology was complementary to RT-PCR for the diagnosis of COVID-19 at least 14 days after onset of symptoms. First line serology testing can be performed with Wantai Ab or Abbott IgG assays, while DiaPro IgG confirmation assay can be used as an efficient confirmation assay.

Keywords: SARS-CoV-2, COVID-19, Serology, Immunoassay, Antibody, ELISA, CLIA, RT-PCR

1. Introduction

The novel severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2) firstly reported in late 2019 in Wuhan [1] and causing coronavirus disease (COVID-19) has spread across the world and lead to a worldwide sanitary crisis. Detection of viral RNA using reverse-transcriptase polymerase chain reaction (RT-PCR) in respiratory samples is the gold standard for early diagnosis of COVID-19. However, sensitivity of this molecular diagnosis starts to decrease at week 3 after onset of symptoms [2]. Complementary to RT-PCR in respiratory samples, SARS-CoV-2 serology allows identification of COVID-19 cases with a higher sensitivity than RT-PCR several days after onset of symptoms [3]. In addition, it can be used to determine the fraction of the population that has been exposed to the virus [3]. However, results of such serosurveys depend on the performance of immunoassays and on the seroprevalence of SARS-CoV-2 which remains quite low, even in COVID-19 hotspots [4]. Given this low prevalence, it is crucial to have robust data evaluating those assays before clinical or epidemiological use. Four immunoassays were evaluated in our study: Euroimmun ELISA SARS-CoV-2 IgG (Euroimmun, Lübeck, Germany), Abbott SARS-CoV-2 IgG (Abbott Diagnostics, Illinois, USA), Wantai SARS-CoV-2 Ab ELISA (Beijing Wantai Biological Pharmacy Enterprise, Beijing, China), and DiaPro COVID-19 IgG Confirmation (Diagnostic Bioprobes, Milano, Italy). The latter assay was used to determine the specificity of SARS-CoV-2 Ab against S1, S2 and N Ag. The first aim was to evaluate the performance of these SARS-CoV-2 immunoassays on a series of 63 COVID-19 patients and 89 pre-pandemic control patients. The second aim was to evaluate their contribution in routine care to confirm or infirm the diagnosis of COVID-19.

2. Material and methods

2.1. Patients and samples

Two complementary studies were performed. First, clinical performance of immunoassays were evaluated on 63 COVID-19 patients tested positive for SARS-CoV-2 RNA by RT-PCR at Tours University Hospital (Table 1 ). SARS-CoV-2 RT-PCR were performed in respiratory samples using Allplex™ 2019-nCOV assay (Seegene, Seoul, Republic of Korea), Abbott RealTime SARS-CoV-2 assay (Abbott Molecular, Illinois, USA) or Bosphore 2019-nCoV detection kit (Anatolia GeneWorks, Istanbul, Turkey) depending on reagents and systems availability. Among the positive RT-PCR results, inconclusive RT-PCR results were defined as results positive only for one gene (E, ORF1ab or N). All 63 patients required an in-patient hospital stay for COVID-19 and had plasma samples collected between April 8th and May 11th 2020. Retrospective testing for SARS-CoV-2 Ab was performed on these samples, collected between 2–36 days after the onset of symptoms. Mild and critical COVID-19 cases were defined according to WHO [31]. Specificity was evaluated on plasma collected before the end of 2019 in 89 patients from occupational medicine (n = 30), emergency or pneumology departments (n = 26) or from patients tested positive by RT-PCR (Allplex™ RP3, Seegene) for seasonal coronaviruses (n = 33, OC43, 229E or NL63) between 3–82 weeks before serology sampling. Positive and negative predictive values of immunoassays were estimated in a context of low (2.4 %) and high seroprevalence (9.8 %) of SARS-CoV-2 Ab. These estimates were based on prevalence of SARS-CoV-2 Ab in healthcare professionals (2.4 %, 108/4 444 tested from June to August 2020) or from patients (9.8 %, 6/61 tested from May to June 2020).

Table 1.

Clinical presentation of patients.

| First study (clinical performance) |

Second study (routine care) |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| RT-PCR+ | Pre-pandemic control group | RT-PCR- | RT-PCR+ | |

| Nb | 63 | 89 | 181 | 22 |

| Age (median/IQR) | 79/67−90 | 30/11−54 | 39/30−50 | 49/31−58 |

| Sex (F:M) | 1.52 | 1.17 | 1.51 | 1.75 |

| Severe outcome | 19/63 (30.2 %) | N/A | N/A | 0 |

| ICU | 18/63 (28.6 %) | NA | N/A | 0 |

| Death | 3/63 (4.7 %) | NA | N/A | 0 |

SARS-CoV-2 RT-PCR assays: Allplex™ 2019-nCOV (Seegene), Abbott RealTime SARS-CoV-2 or Bosphore 2019-nCoV (Anatolia GeneWorks); NA: not available; ICU: intensive care unit.

Second, the contribution of SARS-CoV-2 serology in routine care for the diagnosis of COVID-19 was evaluated on 203 patients tested for SARS-CoV-2 infection by RT-PCR between April 8th and June 11th 2020 (Table 1). Most of these patients were healthcare professionals (167/203, 82.3 %) who did not require an in-patient hospital stay (125/167, 74.9 %). Other patients required an in-patient hospital stay (31/203) or had ambulatory testing (6/203). These patients were tested for SARS-CoV-2 antibodies at least 14 days after RT-PCR testing (unless otherwise specified) between June 1st and June 25th 2020. The entire study was performed according to French Reference Methodology MR-004, after patient information and anonymization of data. Samples were obtained from the registered biological collection DC-2020−3961.

2.2. SARS-CoV-2 immunoassays

Euroimmun ELISA SARS-CoV-2 IgG, Abbott SARS-CoV-2 IgG (Alinity-I analyzer), Wantai SARS-CoV-2 Ab ELISA, and DiaPro COVID-19 IgG Confirmation assays were performed according to the manufacturer’s recommendations. Euroimmun IgG assay was used as first line immunoassay in routine care setting. Positive or undetermined results and results discordant with RT-PCR were confirmed with other assays. For statistical analysis, Euroimmun IgG and Wantai Ab uninterpretable results were considered negative. DiaPro IgG confirmation assay was considered positive when Ab against at least two targets (S1, S2 or nucleoprotein) were detected.

2.3. Statistical analysis

Statistical analysis was carried out using Graphpad Prism v5. Comparison of sensitivity and specificity were performed using McNemar’s test. All tests were two-sided at the 0.05 significance level.

3. Results

3.1. Clinical performance of SARS-CoV-2 immunoassays in the retrospective study

The sensitivity of Euroimmun IgG, Abbott IgG, Wantai Ab, and DiaPro IgG confirmation SARS-CoV-2 assays seven to thirteen days after the onset of symptoms were 30.8, 46.2, 84.6 and 61.5 % (Fig. 1 and Table 2). In this timeframe, the DiaPro IgG confirmation demonstrated an excellent sensitivity for anti-N Ab (100 %), higher than that for anti-S2 Ab (15.4 %, p = 0.003) and higher, although not significantly, than that for anti-S1 Ab (53.8 %; p = 0.13).

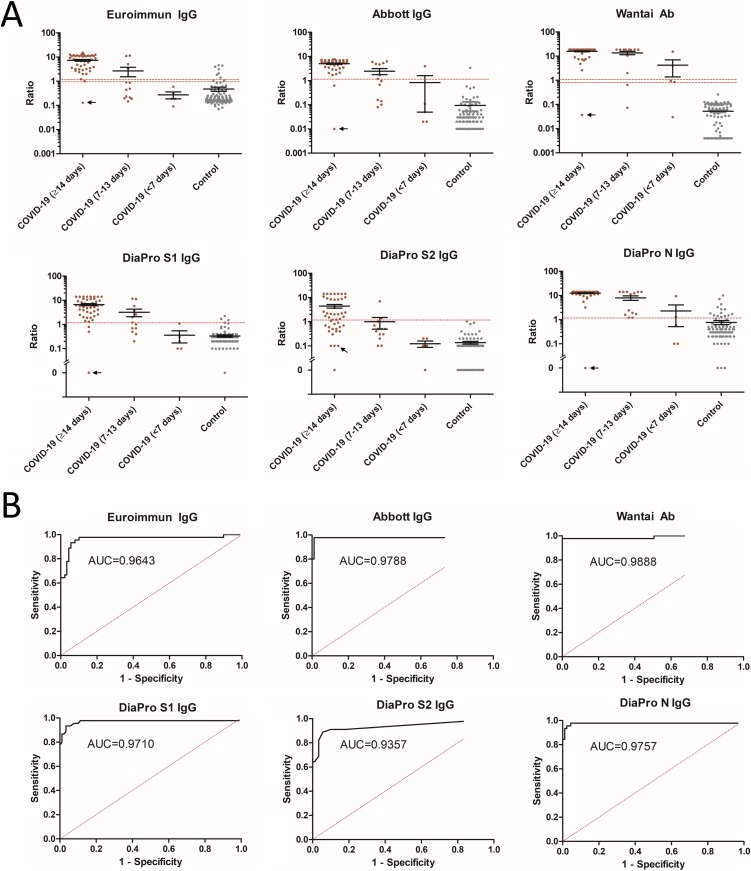

Fig. 1.

Clinical performance of SARS-CoV-2 immunoassays. A) Comparison of SARS-CoV-2 immunoassays results between COVID-19 patients and control patients. Black arrow indicates the heart transplant patient who tested negative with all immunoassays more than 14 days after onset of symptoms. B) ROC curves for evaluation of performances of SARS-CoV-2 immunoassays for samples ≥14 days post onset of symptoms.

The sensitivity of Euroimmun IgG, Abbott IgG, Wantai Ab and DiaPro IgG confirmation SARS-CoV-2 assays 14 days after the onset of symptoms were 95.6 %, 95.6 %, 97.8 % and 95.6 %, respectively (Fig. 1 and Table 2). The DiaPro IgG confirmation assay demonstrated good and similar sensitivities for anti-S1 and anti–N Ab (93.3 % and 97.8 %), both higher than that for anti-S2 Ab (62.2 %, p ≤ 0.002). The single patient who tested negative with all immunoassays was a 61 years old heart transplant patient who experienced fever and myocarditis and had inconclusive RT-PCR result (positive only for the N gene) 26 days post-onset of symptoms (Fig. 1). This patient could have had a false positive RT-PCR result or, less likely false negative serology results because of its immunosuppressive treatments.

The specificity of Euroimmun IgG, Abbott IgG, Wantai Ab and DiaPro IgG confirmation SARS-CoV-2 immunoassay were 92.1 %, 98.9 %, 100 % and 98.9 %, respectively (Fig. 1 and Table 2). Specificity of the DiaPro IgG confirmation assay was lower for anti-N Ab (84.3 %) than for anti-S1 Ab (95.5 %, p = 0.02) and anti-S2 Ab (100.0 %, p = 0.0005). Specificity of Euroimmun IgG assay was lower than other immunoassays, with a significant difference versus Wantai Ab assay (p = 0.02) but not versus Abbott IgG (p = 0.08). False positive Euroimmun IgG results were observed in in an equivalent manner in the different groups of control patients: those with seasonal coronaviruses infections (2/33, both OC43), those from emergency or pneumology departments (3/26) and those from occupational medicine (2/30). False positive Euroimmun IgG results in control patients were associated with a lower ratio (median of 3.13; IQR 1.90–4.40, maximum 5) than those from the COVID-19 patients (median of 7.60, IQR 3.20–11.14, p = 0.02) (Fig. 1). The two different patients with false positive Abbott IgG (1/89) or DiaPro IgG confirmation (1/89) results had a history of infection with Coronavirus 229E.

Positive predictive values based on a 2.4 % and a 9.8 % prevalence rate were 22.9 %/56.8 %; 68.1 %/90.4 %; 100 %/100 %, and 68.1 %/90.4 % for Euroimmun IgG, Abbott IgG, Wantai Ab and DiaPro IgG confirmation SARS-CoV-2 immunoassays. Negative predictive values based on a 2.4 % and a 9.8 % prevalence rate were 99.9 %/99.5 % for Euroimmun IgG, Abbott IgG and DiaPro IgG confirmation, and 99.9 %/99.8 % for Wantai Ab SARS-CoV-2 immunoassays.

Table 2.

Clinical performance of SARS-CoV-2 immunoassays relative to delay with onset of symptoms.

| Assay | Euroimmun IgG | Abbott IgG | Wantai Ab | DiaPro IgG confirmation |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Platform | ELISA | CLIA (Alinity-i) | ELISA | ELISA |

||||

| Antigen | S1 | N | S (RBD) | S1 | S2 | N | ≥2 Ag | |

| Sensitivity | ||||||||

| ≥7−13 dps | n/N | 4/13 | 6/13 | 11/13 | 7/13 | 2/13 | 13/13 | 8/13 |

| % | 30.8 | 46.2 | 84.6 | 53.8 | 15.4 | 100 | 61.5 | |

| 95 % CI | 9.1−61.4 | 19.2−74.9 | 54.6−98.1 | 25.1−80.8 | 1.9−4.5 | 75.3−100.0 | 31.6−86.1 | |

| ≥14 dps | n/N | 43/45 | 43/45 | 44/45 | 42/45 | 28/45 | 44/45 | 43/45 |

| % | 95.6 | 95.6 | 97.8 | 93.3 | 62.2 | 97.8 | 95.6 | |

| 95 % CI | 84.9−99.5 | 84.9−99.5 | 88.2−99.9 | 81.7−98.6 | 46.5−76.2 | 88.2−99.9 | 84.9−99.5 | |

| Specificity | n/N | 82/89 | 88/89 | 89/89 | 85/89 | 89/89 | 75/89 | 88/89 |

| % | 92.1 | 98.9 | 100.0 | 95.5 | 100.0 | 84.3 | 98.9 | |

| 95 % CI | 84.5−96.8 | 93.9−100.0 | 95.9−100.0 | 88.9−98.8 | 95.9−100.0 | 75.0−91.1 | 93.9−100.0 | |

dps: days post-onset of symptoms.

3.2. Contribution of SARS-CoV-2 serology in routine care to confirm or infirm the diagnosis of COVID-19

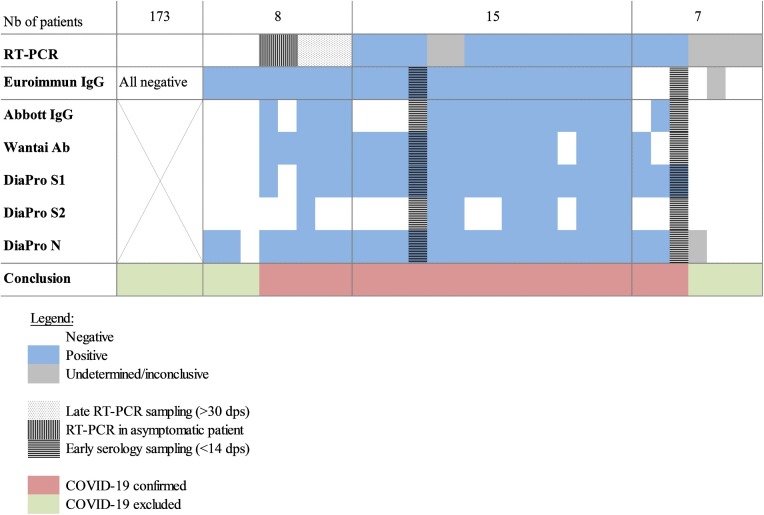

Agreement between RT-PCR and Euroimmun IgG was 68 % (15/22) and 96 % (173/181) for patients who tested positive and negative by RT-PCR, respectively. Results of other immunoassays (Fig. 2 ), the delay between RT-PCR and serology as well as Ct and targets of RT-PCR results were analyzed for these patients (Fig. 3 ). Patients were considered as suffering from COVID-19 if they tested positive with RT-PCR (all targets positive with Ct<38) and/or with at least two out of four SARS-COV-2 immunoassays (Fig. 2). This allowed an accurate definition of 23 COVID-19 cases and 180 non-COVID-19 patients. It lead to the identification of factors associated with false negative and false positive RT-PCR or serology results.

Fig. 2.

Agreement between RT-PCR and serology for 203 patients.

COVID-19 confirmed if positive RT-PCR (>1 gene) and/or Ab detected with two or more immunoassays.

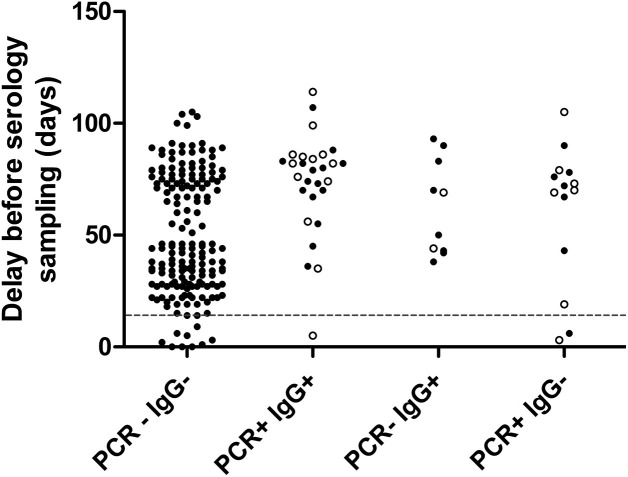

Fig. 3.

Delay between serology and first RT-PCR or onset of symptoms.

Delay between serology and first RT-PCR (plain dots) or onset of symptoms (empty dots). The dashed line represents early serology testing before 14 days after onset of symptoms.

Among the 23 COVID-19 patients, 18/23 were from occupational medicine (8 in-patient hospital stay, non-critical disease). Overall, positive and negative agreement between RT-PCR and COVID-19 diagnosis was 94.6 % (194/203), 78.3 % (18/23), and 97.8 % (176/180), respectively. Overall, positive and negative agreement between Euroimmun IgG and COVID-19 diagnosis was 97.0 % (197/203), 87.0 % (20/23), and 98.3 % (177/180), respectively.

We considered that false positive RT-PCR results occurred in four patients. They were characterized by inconclusive RT-PCR results. Only the N gene was detected, with Ct>38. These patients tested negative with all immunoassays, suggesting the absence of exposure to SARS-CoV-2. Importantly, such inconclusive RT-PCR results were also observed in two COVID-19 patients confirmed positive with all serological assays (Fig. 2), precluding any systematic interpretation of inconclusive RT-PCR results as false positive.

False negative RT-PCR results were observed in two asymptomatic patients, and in three symptomatic patients with late RT-PCR sampling (>1 month after onset of symptoms). These three symptomatic individuals were positive with all immunoassays, confirming the benefit of serology testing for patients with late presentation after onset of symptoms.

False negative serology results were observed in 2/23 COVID-19 patients who were sampled too early for serology testing (<14 days after onset of symptoms, Fig. 2, Fig. 3). Among the 21 remaining COVID-19 patients tested for antibody to SARS-CoV-2 at least 14 days post onset of symptoms, positive agreement with COVID-19 diagnosis was 90.5 % (19/21), 76.2 % (16/21), 90.5 % (19/21) and 95.2 % (20/21) for Euroimmun IgG, Abbott IgG, Wantai Ab and DiaPro IgG confirmation assay, respectively. The DiaPro IgG confirmation assay had the highest positive agreement with COVID-19 diagnosis. It detected anti-S1, -S2 and –N Ab in 20, 12 and 21 of these 21 patients, respectively. In contrast, 5 out of 21 COVID-19 patients were not detected with the Abbott IgG assay. Interestingly, these five COVID-19 patients were also negative for anti-S2 Ab with the DiaPro IgG confirmation assay (Fig. 2). The low positive agreement of Abbott IgG (16/21) with COVID-19 confirmed cases might suggest a lower sensitivity. However, the data could be due to the small sample size and would deserve to be confirmed in larger studies.

4. Discussion

In the first part of our analysis corresponding to the retrospective evaluation, the specificity was 92.1 %, 98.9 %, 100 %, and 98.9 % for Euroimmun IgG, Abbott IgG, Wantai Ab, and DiaPro IgG confirmation SARS-CoV-2 assays, respectively. The sensitivity 14 days after onset of symptoms was 95.6 %, 95.6 %, 97.8 %, and 95.6 % for Euroimmun IgG, Abbott IgG, Wantai Ab, and DiaPro IgG confirmation SARS-CoV-2 assays, respectively. The sensitivity between 7 and 13 days was suboptimal for Wantai Ab (84.6 %) and inadequate (<75 %) for other assays. Our results are in accordance with the available data for which the sensitivity ranges 14 days after onset of symptoms have been described as 61.7–96.0 %, 77.8–100.0 %, 98–100 % and specificity ranges as 86.6–100.0 %, 95.1–100.0 %, 98.0–99.1 % for Euroimmun IgG [[6], [7], [8], [9], [10], [11], [12], [13], [14], [15], [16], [17], [18], [19]], Abbott IgG [9,10,13,[19], [20], [21]] and Wantai Ab immunoassays [15,22,23], respectively. Although we included a collection of serum samples from patients for whom a recent infection by seasonal coronaviruses was documented, we did not notice any specific clustering of false positive results that could be attributed to a particular cross-reactivity.

Clinical performance of the DiaPro IgG confirmation assay (combining S1, S2 and N Ag) were similar to other immunoassays and to the manufacturer’s statement (sensitivity 98 %, specificity 90 %). Interestingly, a higher sensitivity was observed for anti-N Ab and anti-S1 Ab than for anti-S2 Ab (97.8 and 93.3 vs 62.2 %, p ≤ 0.002). This confirmed previous studies based on in-house ELISAs [24]. In contrast, a higher specificity was observed for anti-S2 Ab (100 %) than for anti-N Ab (84.3 %, p = 0.0005). As suggested by previous studies [25,26], combination of S and N Ag probably contributed to the overall good performances of this assay, which had the highest positive agreement of all immunoassays (20/21) with COVID-19 diagnosis in our sub-study performed in real-life routine conditions. Furthermore, this assay has the advantage to allow comparison of the ratio between anti-N IgG and anti-S IgG, which has been associated with the prognosis [26].

We observed a lack of specificity for the Euroimmun IgG assay (92.1 %, CI 95 %: 84.5−96.8 %) in comparison to other assays in our retrospective study. This low specificity was not so problematic in the routine care setting since 98.5 % of the non-COVID-19 patients tested negative with Euroimmun IgG. There are conflicting data in the literature regarding the specificity of this assay. It demonstrated a good specificity (≥ 95 %) in most studies [7,[10], [11], [12],14,18,19], while a minority of studies suggested otherwise [6,9,17]. In this context and given the low prevalence of SARS-CoV-2 Ab, confirmation of positive Euroimmun IgG results seems reasonable. RT-PCR also demonstrated a relative lack of specificity in routine care setting (negative agreement of 97.8 %, 176/180) especially for inconclusive RT-PCR results (only one gene detected, with Ct>38).

Some false negative serology results were associated with early serology sampling (<14 dps), while all false negative RT-PCR results were associated with late RT-PCR sampling (>30dps). This confirms that timing of testing is critical for good sensitivity of SARS-CoV-2 RT-PCR and serology [3]. However, early serology sampling does not explain the relative lack of agreement with COVID-19 diagnosis for Euroimmun IgG (19/21), Abbott IgG (16/21), Wantai Ab (19/21), and DiaPro IgG confirmation assay (20/21) in routine care setting. Similar observations have been made in populations of healthcare professionals, with false negative rates ranging from 1 % [27] to 20 % [[28], [29], [30]] several weeks after disease. This could be due to the high proportion of patients with mild COVID-19, resulting in low rates of seroconversion [28].

Our study confirms that Abbott IgG, Wantai Ab and DiaPro IgG confirmation assays are suitable assays for the diagnosis of COVID-19 at least 14 days after onset of symptoms. Main advantages of these assays are their automation (Abbott IgG), their optimal clinical performance (Wantai Ab) and their ability to differentiate between anti-N, -S1 and –S2 Ab (DiaPro IgG confirmation). DiaPro IgG confirmation assay has a low throughput (four wells per patient) which is adequate for confirmation testing. Euroimmun IgG assay can also be used for the diagnosis of COVID-19 if positive results are confirmed with another assay to compensate for its low specificity.

The huge impact of the SARS-CoV-2 emergence in public health justifies extensive seroepidemiological studies to survey its spread in various populations and numerous settings. There is a burst of serologic assays rolling out in different formats, including simple rapid tests. Our study shows that specificity may be highly variable among available immunoassays for antibody to SARS-CoV-2. Poor specificity of an assay in a population where prevalence and incidence of COVID-19 are low will lead to irrelevant data. Our study, as others, stresses on the absolute necessity to use only carefully validated assays to provide epidemiological data useful to public health decision makers.

Funding

This research did not receive any specific grant from funding agencies in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

Contribution

ER carried out the experiment. JM, CP, ER and YA analyzed the data. JM, CP, FB, KS and CGG designed the study and wrote the manuscript with support from AL.

AG, SM, AL, LB, GD and HB contributed to the design, patient management and data collection.

Acknowledgments

The authors thanks Brigitte Berthon, Pascale Mezieres and Amélie Grivot for their contribution to the experiments, and Léo Léger for its contribution to data collection and analysis. Dr. Marchand-Adam reports financial relationships from Boehringer Ingelheim, Roche and Novartis outside the submitted work. Dr. Lemaignen reports financial relationships from Gilead, Pfizer and MSD outside the submitted work.

References

- 1.Zhu N., Zhang D., Wang W., Li X., Yang B., Song J., Zhao X., Huang B., Shi W., Lu R., Niu P., Zhan F., Ma X., Wang D., Xu W., Wu G., Gao G.F., Tan W. China novel coronavirus investigating and research team, a novel coronavirus from patients with pneumonia in China, 2019. N. Engl. J. Med. 2020;382:727–733. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa2001017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Wölfel R., Corman V.M., Guggemos W., Seilmaier M., Zange S., Müller M.A., Niemeyer D., Jones T.C., Vollmar P., Rothe C., Hoelscher M., Bleicker T., Brünink S., Schneider J., Ehmann R., Zwirglmaier K., Drosten C., Wendtner C. Virological assessment of hospitalized patients with COVID-2019. Nature. 2020 doi: 10.1038/s41586-020-2196-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Peeling R.W., Wedderburn C.J., Garcia P.J., Boeras D., Fongwen N., Nkengasong J., Sall A., Tanuri A., Heymann D.L. Serology testing in the COVID-19 pandemic response. Lancet Infect. Dis. 2020 doi: 10.1016/S1473-3099(20)30517-X. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Eckerle I., Meyer B. SARS-CoV-2 seroprevalence in COVID-19 hotspots. Lancet. 2020 doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(20)31482-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Lassaunière R., Frische A., Harboe Z.B., Nielsen A.C., Fomsgaard A., Krogfelt K.A., Jørgensen C.S. Evaluation of nine commercial SARS-CoV-2 immunoassays. Infect. Dis. (except HIV/AIDS) 2020 doi: 10.1101/2020.04.09.20056325. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Van Elslande J., Houben E., Depypere M., Brackenier A., Desmet S., André E., Van Ranst M., Lagrou K., Vermeersch P. Diagnostic performance of seven rapid IgG/IgM antibody tests and the Euroimmun IgA/IgG ELISA in COVID-19 patients. Clin. Microbiol. Infect. 2020 doi: 10.1016/j.cmi.2020.05.023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Beavis K.G., Matushek S.M., Abeleda A.P.F., Bethel C., Hunt C., Gillen S., Moran A., Tesic V. Evaluation of the EUROIMMUN Anti-SARS-CoV-2 ELISA assay for detection of IgA and IgG antibodies. J. Clin. Virol. 2020;129:104468. doi: 10.1016/j.jcv.2020.104468. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Jääskeläinen A.J., Kuivanen S., Kekäläinen E., Ahava M.J., Loginov R., Kallio-Kokko H., Vapalahti O., Jarva H., Kurkela S., Lappalainen M. Performance of six SARS-CoV-2 immunoassays in comparison with microneutralisation. J. Clin. Virol. 2020;129:104512. doi: 10.1016/j.jcv.2020.104512. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Nicol T., Lefeuvre C., Serri O., Pivert A., Joubaud F., Dubée V., Kouatchet A., Ducancelle A., Lunel-Fabiani F., Le Guillou-Guillemette H. Assessment of SARS-CoV-2 serological tests for the diagnosis of COVID-19 through the evaluation of three immunoassays: two automated immunoassays (Euroimmun and Abbott) and one rapid lateral flow immunoassay (NG Biotech) J. Clin. Virol. 2020;129:104511. doi: 10.1016/j.jcv.2020.104511. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kohmer N., Westhaus S., Rühl C., Ciesek S., Rabenau H.F. Clinical performance of different SARS-CoV-2 IgG antibody tests. J. Med. Virol. 2020 doi: 10.1002/jmv.26145. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Montesinos I., Gruson D., Kabamba B., Dahma H., Van den Wijngaert S., Reza S., Carbone V., Vandenberg O., Gulbis B., Wolff F., Rodriguez-Villalobos H. Evaluation of two automated and three rapid lateral flow immunoassays for the detection of anti-SARS-CoV-2 antibodies. J. Clin. Virol. 2020;128:104413. doi: 10.1016/j.jcv.2020.104413. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kohmer N., Westhaus S., Rühl C., Ciesek S., Rabenau H.F. Brief clinical evaluation of six high-throughput SARS-CoV-2 IgG antibody assays. J. Clin. Virol. 2020;129:104480. doi: 10.1016/j.jcv.2020.104480. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Krüttgen A., Cornelissen C.G., Dreher M., Hornef M., Imöhl M., Kleines M. Comparison of four new commercial serologic assays for determination of SARS-CoV-2 IgG. J. Clin. Virol. 2020;128:104394. doi: 10.1016/j.jcv.2020.104394. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Weidner L., Gänsdorfer S., Unterweger S., Weseslindtner L., Drexler C., Farcet M., Witt V., Schistal E., Schlenke P., Kreil T.R., Jungbauer C. Quantification of SARS-CoV-2 antibodies with eight commercially available immunoassays. J. Clin. Virol. 2020;129:104540. doi: 10.1016/j.jcv.2020.104540. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Meyer B., Torriani G., Yerly S., Mazza L., Calame A., Arm-Vernez I., Zimmer G., Agoritsas T., Stirnemann J., Spechbach H., Guessous I., Stringhini S., Pugin J., Roux-Lombard P., Fontao L., Siegrist C.-A., Eckerle I., Vuilleumier N., Kaiser L. Geneva center for emerging viral diseases, validation of a commercially available SARS-CoV-2 serological immunoassay. Clin. Microbiol. Infect. 2020 doi: 10.1016/j.cmi.2020.06.024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Tuaillon E., Bolloré K., Pisoni A., Debiesse S., Renault C., Marie S., Groc S., Niels C., Pansu N., Dupuy A., Morquin D., Foulongne V., Bourdin A., Le Moing V., Van de Perre P. Detection of SARS-CoV-2 antibodies using commercial assays and seroconversion patterns in hospitalized patients. J. Infect. 2020 doi: 10.1016/j.jinf.2020.05.077. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.GeurtsvanKessel C.H., Okba N.M.A., Igloi Z., Bogers S., Embregts C.W.E., Laksono B.M., Leijten L., Rokx C., Rijnders B., Rahamat-Langendoen J., van den Akker J.P.C., van Kampen J.J.A., van der Eijk A.A., van Binnendijk R.S., Haagmans B., Koopmans M. An evaluation of COVID-19 serological assays informs future diagnostics and exposure assessment. Nat. Commun. 2020;11:3436. doi: 10.1038/s41467-020-17317-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Theel E.S., Harring J., Hilgart H., Granger D. Performance characteristics of four high-throughput immunoassays for detection of IgG antibodies against SARS-CoV-2. J. Clin. Microbiol. 2020 doi: 10.1128/JCM.01243-20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Chew K.L., Tan S.S., Saw S., Pajarillaga A., Zaine S., Khoo C., Wang W., Tambyah P., Jureen R., Sethi S.K. Clinical evaluation of serological IgG antibody response on the Abbott Architect for established SARS-CoV-2 infection. Clin. Microbiol. Infect. 2020 doi: 10.1016/j.cmi.2020.05.036. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Meschi S., Colavita F., Bordi L., Matusali G., Lapa D., Amendola A., Vairo F., Ippolito G., Capobianchi M.R., Castilletti C. INMICovid-19 laboratory team, performance evaluation of Abbott ARCHITECT SARS-CoV-2 IgG immunoassay in comparison with indirect immunofluorescence and virus microneutralization test. J. Clin. Virol. 2020;129:104539. doi: 10.1016/j.jcv.2020.104539. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Zhao J., Yuan Q., Wang H., Liu W., Liao X., Su Y., Wang X., Yuan J., Li T., Li J., Qian S., Hong C., Wang F., Liu Y., Wang Z., He Q., Li Z., He B., Zhang T., Ge S., Liu L., Zhang J., Xia N., Zhang Z. Antibody responses to SARS-CoV-2 in patients of novel coronavirus disease 2019. Infect. Dis. (except HIV/AIDS) 2020 doi: 10.1101/2020.03.02.20030189. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Ong D.S.Y., de Man S.J., Lindeboom F.A., Koeleman J.G.M. Comparison of diagnostic accuracies of rapid serological tests and ELISA to molecular diagnostics in patients with suspected coronavirus disease 2019 presenting to the hospital. Clin. Microbiol. Infect. 2020 doi: 10.1016/j.cmi.2020.05.028. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Brochot E., Demey B., Touze A., Belouzard S., Dubuisson J., Schmit J.-L., Duverlie G., Francois C., Castelain S., Helle F. Anti-spike, anti-nucleocapsid and neutralizing antibodies in SARS-CoV-2 inpatients and asymptomatic carriers. Infect. Dis. (except HIV/AIDS) 2020 doi: 10.1101/2020.05.12.20098236. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Schnurra C., Reiners N., Biemann R., Kaiser T., Trawinski H., Jassoy C. Comparison of the diagnostic sensitivity of SARS-CoV-2 nucleoprotein and glycoprotein-based antibody tests. J. Clin. Virol. 2020;129:104544. doi: 10.1016/j.jcv.2020.104544. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Sun B., Feng Y., Mo X., Zheng P., Wang Q., Li P., Peng P., Liu X., Chen Z., Huang H., Zhang F., Luo W., Niu X., Hu P., Wang L., Peng H., Huang Z., Feng L., Li F., Zhang F., Li F., Zhong N., Chen L. Kinetics of SARS-CoV-2 specific IgM and IgG responses in COVID-19 patients. Emerg. Microbes Infect. 2020;9:940–948. doi: 10.1080/22221751.2020.1762515. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Fafi-Kremer S., Bruel T., Madec Y., Grant R., Tondeur L., Grzelak L., Staropoli I., Anna F., Souque P., Fernandes-Pellerin S., Jolly N., Renaudat C., Ungeheuer M.-N., Schmidt-Mutter C., Collongues N., Bolle A., Velay A., Lefebvre N., Mielcarek M., Meyer N., Rey D., Charneau P., Hoen B., De Seze J., Schwartz O., Fontanet A. Serologic responses to SARS-CoV-2 infection among hospital staff with mild disease in eastern France. EBioMedicine. 2020:102915. doi: 10.1016/j.ebiom.2020.102915. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Rijkers G., Murk J.-L., Wintermans B., van Looy B., van den Berge M., Veenemans J., Stohr J., Reusken C., van der Pol P., Reimerink J. Differences in antibody kinetics and functionality between severe and mild SARS-CoV-2 infections. J. Infect. Dis. 2020:jiaa463. doi: 10.1093/infdis/jiaa463. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Pallett S.J.C., Rayment M., Patel A., Fitzgerald-Smith S.A.M., Denny S.J., Charani E., Mai A.L., Gilmour K.C., Hatcher J., Scott C., Randell P., Mughal N., Jones R., Moore L.S.P., Davies G.W. Point-of-care serological assays for delayed SARS-CoV-2 case identification among health-care workers in the UK: a prospective multicentre cohort study. Lancet Respir. Med. 2020 doi: 10.1016/S2213-2600(20)30315-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Brandstetter S., Roth S., Harner S., Buntrock‐Döpke H., Toncheva A.A., Borchers N., Gruber R., Ambrosch A., Kabesch M. Symptoms and immunoglobulin development in hospital staff exposed to a SARS-CoV-2 outbreak. Pediatr. Allergy Immunol. 2020 doi: 10.1111/pai.13278. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.WHO/2019-nCoV/clinical/2020.5, 2020. https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/clinical-management-of-covid-19. (Accessed 21 August 2020).