Highlights

-

•

This survey collected information about depression, anxiety, and physical activity levels of 1,046 older adults living in North America under current social distancing guidelines during the COVID-19 pandemic.

-

•

The primary question addressed by the study was whether total physical activity levels and physical activity intensities performed by older adults during COVID-19-related SDG was related to mental health symptoms.

-

•

The results of this study showed that greater total physical activity levels were associated with lower scores on the Geriatric Depression Scale.

-

•

Additionally, a hierarchical regression analysis suggests that light and vigorous-intensity physical activity were significant, independent contributors towards depression symptoms in this population.

-

•

These findings suggest that higher levels of physical activity levels may help alleviate some of the negative mental health symptoms experienced by older adults, while social distancing guidelines are followed during the COVID-19 pandemic.

Key Words: Mood, activity, COVID-19

Abstract

Objective

To determine the relationship between the amount and intensity of physical activity performed by older adults in North America (United States and Canada) and their depression and anxiety symptoms while currently under social distancing guidelines (SDG) for the COVID-19 pandemic.

Design

Descriptive cross-sectional study.

Setting

Online survey conducted between April 9 and April 30, 2020, during the COVD-19 pandemic.

Participants

About 1,046 older adults over the age of 50 who live in North America.

Measurements

Participants were asked about their basic demographic information, current health status, and the impact of the current SDG on their subjective state of mental health. Participants completed the Physical Activity Scale for the Elderly, to determine the amount and intensity of physical activity performed, as well as both the Geriatric Depression Scale and Geriatric Anxiety Scale, to ascertain the extent of their depression and anxiety-like symptoms.

Results

Ninety-seven percent of participants indicated that they adhered to current SDG “Most of the time” or “Strictly.” Participants who performed greater levels of physical activity experienced lower levels of depression-like symptoms when age, sex, and education were accounted for; however, no relationship between physical activity and anxiety-like symptoms was found. A hierarchical regression analysis that incorporated the intensity of physical activity performed (light, moderate, and vigorous) in the model indicated that greater light and strenuous activity, but not moderate, predicted lower depression-like symptoms.

Conclusions

These results suggest that performing even light physical activity during the COVID-19 pandemic may help alleviate some of the negative mental health impacts that older adults may be experiencing while isolated and adhering to SDG during the COVID-19 pandemic.

OBJECTIVE

The recent worldwide outbreak of a new type of coronavirus (SARS-CoV-2) has reached over 140 countries and has been declared a pandemic by the World Health Organization.1 The most common clinical manifestation of SARS-CoV-2 includes severe life-threatening respiratory tract infections (COVID-19) to which older adults and those with comorbidities (e.g., hypertension, cardiovascular disease, diabetes, chronic respiratory diseases, and chronic kidney disease) are most susceptible.2, 3, 4 As a result, the United States and Canada have issued social distancing guidelines (SDG), and in certain parts of each country, stay-at-home orders intended to combat the spread of the disease and protect fragile healthcare systems. Due to this increased mortality risk for older adults, the CDC has indicated that older individuals, in particular, should strictly adhere to SDG and stay-at-home as much as possible.5 While these changes can reduce transmission, protect over-burdened healthcare systems, and save the lives of many in these high-risk groups, they also present a major public health concern given the well-established increased risk of mental health problems associated with social isolation in older adults.3 Self-isolation will likely disproportionately affect older adults whose social contact often takes place outside of the home (i.e., community centers, places of worship, volunteering).6

Humans are social beings, and the quantity and quality of human social interactions can directly affect mental health, physical health, and morbidity risk.7 Due to the probable increase in the incidence of serious health complications from SARS-CoV-2, older adults, particularly those with pre-existing conditions, are now undergoing physical and social isolation, which may increase the incidence and severity of anxiety and depression among this population.6 Social isolation and perceived social isolation (i.e., loneliness) are significant risk factors for cognitive decline, anxiety, and depression,8 and are associated with increased levels of all-cause mortality in older adults.9 A recent report of over 3,000 older adults between the ages of 57–85 showed that increased social isolation was predictive of more severe depression and anxiety symptoms.10 While not fully understood, health-related declines associated with social isolation and loneliness may be a consequence of dysregulated health behaviors such as social connectedness and physical activity.11 , 12 Not surprisingly, sedentary behavior is a significant predictor of all-cause mortality,13 has been shown to negatively affect mood and depressive symptomatology,14 and is associated with cognitive decline in older adults.15 Unfortunately, social isolation is generally linked with increased sedentary behavior and reduced physical activity in older adults16 and recent reports suggest the COVID-19 pandemic may be leading many older adults to perform less physical activity.17 , 18

Among older adults, physical activity and aerobic exercise training appear to have anxiolytic and antidepressant effects.14 Large epidemiological studies suggest that physical activity is associated with better mental health and resilience to psychological distress, such as depression and anxiety symptoms.19 , 20 Of note, the benefits of physical activity for mental health may be dependent on the intensity of physical activity performed.21 Recently, some data suggest that the positive relationship between physical activity and mental health extend to older adults, and that physical activity uniquely contributes to depression symptoms in this population.22 Meanwhile, experimental data show that engagement in physical activity over time-frames similar to those of the current pandemic (i.e., 4–10 weeks) can lead to improvements in both anxiety and depressive symptomology in various populations, including older adults.23, 24, 25, 26, 27

COVID-19 has changed the way many older adults are currently living their lives, forcing many into isolation who may have previously been more social. Additionally, the COVID-19 pandemic and the increased mortality risk associated with the disease may cause older adults to experience greater anxiety and depression-like symptoms. It is, therefore, essential to determine safe ways for older adults to manage mental health-related symptoms that may be exacerbated during the pandemic. While recent reports have called for older adults to increase their levels of physical activity to improve their immune system, reduce obesity risk, and improve mental health, no empirical studies have looked at the relationship between physical activity levels and mental health symptoms in older adults during the COVID-19 pandemic. It remains to be seen whether the physical activity levels are associated with their depression and anxiety-like symptoms while adhering to the current SDG. Given previous work suggesting older adults performing greater amounts of physical activity may experience fewer mental health problems, we hypothesized that total physical activity levels would be negatively associated with the anxiety and depression symptoms of older adults currently living under COVID-19-related SDG. To test this hypothesis, we surveyed 1,046 adults over the age of 50 who currently live in the United States and Canada under the COVID-19-related SDG, to examine associations between current physical activity levels and anxiety and depression-like symptoms.

METHODS

Study Design and Participants

The Mood and Activity Survey study during the COVID-19 pandemic is a descriptive cross-sectional study that drew from a sample of adults over the age of 50, between April 9 and April 30, 2020, during the COVD-19 pandemic.

Survey

An online Qualtrics survey of 136 questions (estimated to take approximately 15 minutes to complete) was used to collect data. The survey was approved by the University of Maryland Institutional Review Board, and written informed consent was obtained from all participants prior to proceeding with the survey (see Supplementary File 1 for a PDF version of the survey). The survey included questions regarding demographic information, geographical location (zip code), current health status, classification as a first responder, the impact of the current SDG on their subjective state of physical and social isolation, in addition to well-known and validated instruments such as the Physical Activity Scale for the Elderly (PASE), Geriatric Depression Scale (GDS), and Geriatric Anxiety Scale (GAS). Social media advertising was used as the primary method of recruitment to reach the targeted population (age 50+) living in the United States and Canada. Additionally, we leveraged our pre-existing social media and outreach infrastructure from our laboratory and website (https://E4BH.com) to recruit volunteers to complete the survey.

PASE Questionnaire

The PASE is a valid and widely used questionnaire to address physical activity among older adults over a 7-day period.28 , 29 Briefly, participants were asked to provide information as to the frequency (days/week) and duration (hours/day) they participated in sedentary and active behaviors. Originally designed to quantify and account for the intensity and type of active behaviors common in older adults, the survey included activities such as walking outside, recreational aerobic (light, moderate, and vigorous) and strength exercise, yard work, gardening, house repairs, and caring for others. Each activity was scored based on the original Washburn et al scale in which the frequency and duration were used as anchors, the activity type was assigned an empirically derived weight, and the score for each activity type was the product of the 2.29 Each activity type and their associated scores were then categorized into either leisure (walking outside and recreational exercise), or household (yard work, gardening, home repairs, and caring for others) physical activity, with the total PASE score representing the sum of these 2 categories.

GDS Questionnaire

The GDS is an established and well-validated measure of depressive symptoms among older adults.30 The GDS includes 30 questions to which respondents answer “Yes” or “No.” The GDS focuses on psychiatric symptoms vs. somatic symptoms by assessing an individual's level of enjoyment, interests, and social interactions in the 7 days leading to the day of testing. A point is given to each answer that indicates depression. A score of 0–9 is considered normal, 10–19 is considered an indicator of mild depression, and 20–30 suggests severe depression.30

GAS Questionnaire

The GAS is a 30-item self-report measure designed to assess cognitive, somatic, and affective anxiety symptoms in older adults.31 Respondents are instructed to report the frequency that they experienced each anxiety symptom during the past week on a 4-point Likert scale from 0 (not at all) to 3 (all the time). A total anxiety score, with higher scores indicating higher levels of anxiety, is calculated by summing the self-reported ratings on items 1–25. A score of 0–11 is an indicator of minimal anxiety symptoms, 12–21 is considered an indicator of mild anxiety symptoms, 22–27 is considered an indicator of moderate anxiety symptoms, and scores of 28 and higher are considered an indication of severe symptoms.31 The last 5 items identify areas of concern.

Statistical Analysis

Multiple linear regression analyses were used to determine the independent effect of total physical activity levels on total depression and anxiety symptoms. Participants were able to skip individual questions and, due to missing data points, it was only possible to calculate 848 total GDS scores and 677 total GAS scores. A chi-square test of independence indicated that participants who completed the full GDS were found to be of similar age (X 2(4) = 2.83, p = 0.59), sex (X 2(1) = 0.52, p = 0.47), and had slightly education values (X 2(5) = 12.11, p = 0.03) than those who did not complete the full GDS. Additionally, an independent groups t-test indicated that individuals who completed the GDS had significantly higher total PASE scores (t(280) = 5.75, p <0.001) than those who did not complete the GDS. Furthermore, participants who completed the GAS were of similar age (X 2(4) = 4.54, p = 0.34), had slightly higher education (X 2(5) = 15.08, p = 0.01), a greater percentage of female respondents (X 2(1) = 5.34, p = 0.02), and had higher total physical activity levels (t(770) = 6.68, p < 0.001). Both GDS and GAS scores were separately regressed on the PASE total score, adjusting for age, sex, and education. All multiple linear regression models were tested for data points with abnormal leverage (hat value >3 times average), influence (Cook's D >0.5), and discrepancy (studentized residuals greater >3). Based on an exclusionary criterion of violating more than one of these three heuristics, no data points had to be removed from any of the analyses. If a significant relationship between PASE total and GDS or GAS scores was found, a hierarchical regression was then performed by adding PASE intensity subscales (light, moderate, and strenuous) to a base model of age, sex, and education. The hierarchical regression was used to determine the unique contribution of each physical activity intensity for predicting mental health symptoms. All statistical analyses were performed with R version 3.6.32

RESULTS

Participants

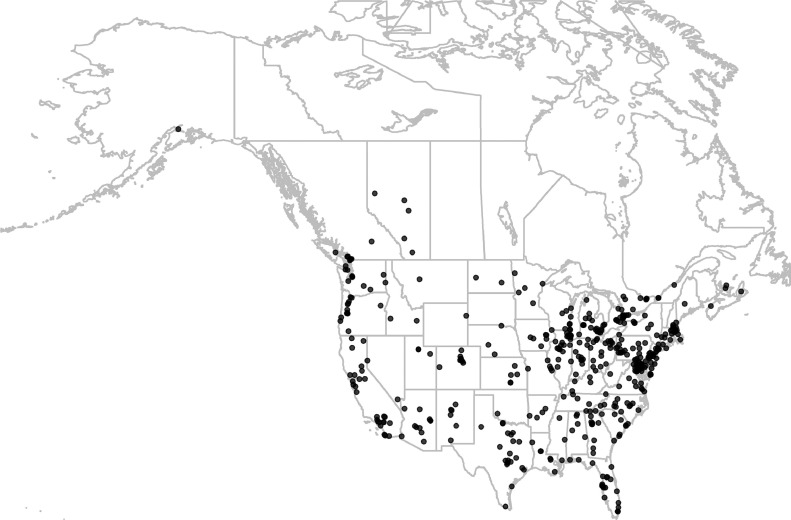

Demographic, health, physical activity, depression, anxiety, and COVID-19-related data for all participants are provided in Table 1 . Approximately 50,000 individuals were reached by the Facebook advertisement, 3,000 of whom engaged with the advertisement (reaching the informed consent page with the survey link), and 1,700 individuals started the survey. We received 1,369 completed responses and excluded 323 participants who either indicated they were younger than 50, or who did not provide an age in their response. Our study sample consisted of 1,046 older adults (ages ≥50) who currently reside in either the United States or Canada. Our respondents were predominantly white (86.5%) and female (80%), less than 0.2% of participants had tested positive for COVID-19, and approximately 3.5% indicated first responder status. Additionally, 97.7% of participants indicated adherence to current SDG “Most of the time” or “Strictly.” Approximately 37.6% of participants indicated that they performed “Much less” or “Somewhat less” physical activity since the start of COVID-19 SDG, while 35.7% of participants indicated performing “About the same” compared to before the COVID-19 SDG. A visualization of where our sample resides was created using zip codes provided by 527 of our respondents (Fig. 1 ). Because providing a zip code was optional and only 527 usable zip code responses of the total sample of 1,046 were obtained, we were unable to conduct any country specific analysis of the data.

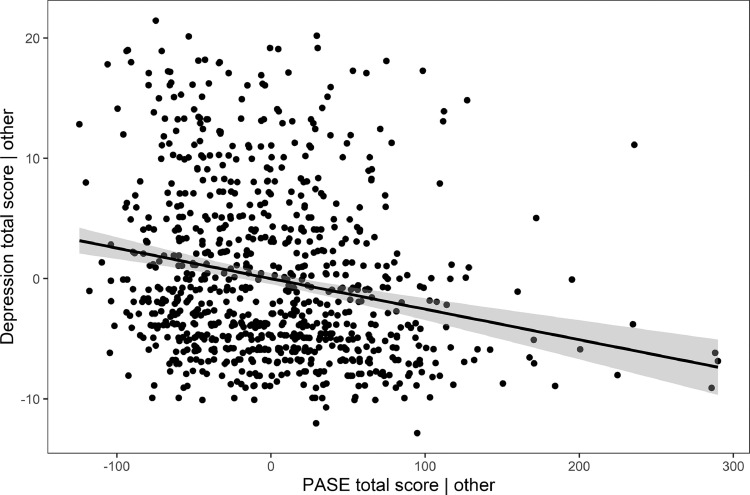

FIGURE 2.

Residualized plot of total physical activity (PASE) scores on total depression scores after controlling for age, sex, and education.

TABLE 1.

Demographic Information of Survey Respondents

| Total Sample (n = 1,046) N (%) |

||

|---|---|---|

| Demographics | Age | |

| 50–59 | 292 (27.9%) | |

| 60–69 | 424 (40.5%) | |

| 70–79 | 257 (24.5%) | |

| 80–89 | 67 (6.4%) | |

| >90 | 5 (0.4%) | |

| Sex | ||

| Male | 212 (20%) | |

| Female | 834 (80%) | |

| Education | ||

| <College | 123 (11.8%) | |

| >College | 923 (88.2%) | |

| History of chronic disease | ||

| Strokea 102 | 29 (3.1%) | |

| Cardiovasculara 87 | 131 (13.7%) | |

| Pulmonarya 71 | 176 (18.1%) | |

| Diabetesa 72 | 158 (16.2%) | |

| Heart attacka 100 | 36 (3.8%%) | |

| Racea 1 | ||

| White | 905 (86.5%) | |

| Black | 14 (1.3%) | |

| Hispanic | 18 (1.7%) | |

| Asian | 34 (3.2%) | |

| American Indian/Alaskan/Native Hawaiian/Pacific Islander | 6 (0.5%) | |

| More than one | 26 (2.4%) | |

| Prefer not to say | 42 (4%) | |

| COVID-19 questionnaire | Tested positive for COVID-19a 111 | 2 (0.19%) |

| Anyone in house test positive for COVID-19a 110 | 3 (0.28%) | |

| Adherence to the stay-at-home ordera 24 | ||

| Strictly | 734 (71.8%) | |

| Most of the time | 265 (25.9%) | |

| Sometimes | 45 (4.4%) | |

| Seldom | 3 (0.29%) | |

| Not at all | 4 (0.39%) | |

| First responder statusa 24 | 35 (3.4%) | |

| Anxiety, depression and physical activity | GAS (Mean, SD)a 369 | 10.1 (6.8) |

| Minimal | 190 (28.1%) | |

| Mild | 434 (64.1%) | |

| Moderate | 47 (6.9%) | |

| Severe | 6 (0.8%) | |

| GDS (Mean, SD)a 198 | 9.01 (7.16) | |

| Mild | 216 (25.5%) | |

| Normal | 535 (63.1%) | |

| Severe | 97 (11.4%) | |

| PASE (Mean, SD) | ||

| Total | 102.5 (63.8) | |

| Light activity | 2.3 (8.3) | |

| Moderate activity | 1.4 (6.5) | |

| Vigorous activity | 2.5 (9.7) | |

| Change in physical activity after COVID-19a 26 | ||

| Much lower | 148 (14.2%) | |

| Somewhat lower | 245 (23.4%) | |

| About the same | 373 (35.7%) | |

| Somewhat greater | 160 (15.3%) | |

| Much greater | 94 (9.0%) |

Notes: Demographic, health, and COVID-19-related questions are reported as count and percent of the total responses. Mean and standard deviations (SD) of the Geriatric Anxiety Scores (GAS), Geriatric depression scores (GDS), and Physical Activity Scale for the Elderly (PASE) total and subscale scores are reported.

Indicates the number of missing data points.

FIGURE 1.

A map of geographic locations of 527 participants over age 50 who completed the survey and provided a zip code or postal code.

Of the participants with total GDS scores reported (n = 848), 25.5% would be categorized as having mild depression, 63.1% of respondents would be categorized as moderately depressed, and 11.4% of respondents would be categorized as severely depressed. Of the participants with recorded total GAS scores (n = 677), 28.1% of participants would be categorized as having minimal anxiety like symptoms, 64.1% of participants would be categorized as having mild anxiety symptoms, 6.9% would be categorized as having moderate anxiety symptoms, while 0.8% of participants would be categorized as having severe anxiety symptoms.

Total Physical Activity and Symptoms of Anxiety and Depression

We examined the association between the total amount of physical activity performed and the extent of depression and anxiety-like symptoms of adults over the age of 50 currently under COVID-19-related SDG. First, total GAS scores were regressed on participants’ total physical activity score, age, sex, and education. The overall multiple regression model was statistically significant (adjusted R 2 = 0.02, F(11, 617) = 2.85, p = 0.010), accounting for 2% of the variance in anxiety scores. However, only sex was a significant predictor of total GAS scores with an unstandardized coefficient of b = −2.44 [t(617) = −6.38, p <0.001, β = −0.15], after controlling for age, PASE total, and education. Total physical activity was not a significant predictor of anxiety symptoms, with an unstandardized coefficient of b = −0.01 [t(617) = −0.48, p = 0.629, β = −0.02], after controlling for age, sex, and education.

Next, total depression symptoms scores were regressed on total PASE, age, sex, and education. The overall multiple regression model was statistically significant (adjusted R 2 = 0.072, F(11,835) = 6.97, p <0.001). The model accounted for 7.2% of the variance in total depression scores. Specifically, total physical activity, sex, and age were significant predictors of total depression symptoms. The unstandardized regression coefficient for PASE total was b = −0.03 [t(835) = −6.38, p <0.001, β = −0.22]. The standardized coefficient of β = −0.22 suggests that a one standard deviation increase in PASE total score would predict a 0.22 standard deviation decrease in a participant's expected GDS score when controlling for age, sex, and education. Males were predicted to have a GDS score 1.65 points lower than females (b = −1.65 [t(835) = −2.77, p = 0.006, β = −0.09]), controlling for total physical activity, age, and education. Additionally, compared to individuals who were 50–59 years old, individuals aged 70–79 and 80–89 years old were predicted to have depression scores 2.07 [t(835) = −2.77, p = 0.002, β = −0.12] and 3.32 [t(835) = −2.77, p = 0.002, β = −0.11] points lower, respectively, after controlling for total physical activity, sex, and education. Depression scores at each education level were not significantly different from the referent college educated group. The unstandardized regression coefficients (b) and standardized regression coefficients (β) for all variables in the multiple linear regression are reported in Table 2 .

TABLE 2.

Multiple Linear Regression Results for Total Physical Activity as a Predictor of Symptoms of Depression, Controlling for Age, Sex, and Education

| Predictor Variables | b (SE) | Β | p Value |

|---|---|---|---|

| PASE total | −0.03 (<0.01) | −0.22b | <0.001 |

| Age | |||

| 60–69 | −0.75 (0.58) | −0.03 | 0.45 |

| 70–79 | −3.11 (0.67) | −0.12a | 0.002 |

| 80–89 | −3.16 (1.05) | −0.11a | 0.002 |

| 90+ | 0.90 (3.13) | 0.03 | 0.37 |

| Sex | −2.77 (0.60) | −0.09a | 0.006 |

| Education | |||

| Some HS | −1.52 (2.24) | −0.05 | 0.13 |

| HS diploma/GED | 1.64 (0.91) | 0.06 | 0.10 |

| Some college/vocation | −0.02 (0.64) | −0.01 | 0.99 |

| Graduate | −1.53 (0.66) | −0.06 | 0.13 |

| Doctorate | −0.34 (0.88) | −0.01 | 0.74 |

| Model | Adj. R2 | F (df) | p value |

| Full model | 0.072b | 3.28 (11, 787) | <0.001 |

Notes: Nonstandardized (b) and standardized beta (β) coefficients, along with standard errors (SE) are reported.

Referent education is college degree. Referent age is 50–59.

p <0.01.

p <0.001.

Physical Activity Intensity and Symptoms of Depression

A hierarchical multiple regression analysis was further conducted to explore the unique contribution of different intensities of physical activity for explaining variance in depression symptoms while controlling for age, sex, and education. Variables that explain variance in depression symptoms were entered in two steps. In step 1, total depression score was the dependent variable, and (a) age, (b) sex, and (c) education were the independent variables. In step 2, the subscales of the PASE (in order of light, moderate, and then vigorous intensity activity) were subsequently added to the step 1 model. Before performing the hierarchical multiple regression, the independent variables were examined for collinearity. Results of the variance inflation factor (all less than 1.5), and collinearity tolerance (all greater than 0.7) suggest the estimated β’s are well supported.

The results of step 1 indicate that the variance accounted for (R 2) by the first model containing age, sex, and education equaled 0.039 (adjusted R 2 = 0.028), which was significant (F (10,836) = 3.43, p <0.001). Sex was the only significant predictor (β = −0.15, p = 0.002) of total depression score in step 1. In step 2, PASE subscales (light, moderate, and vigorous intensity) were hierarchically entered into the regression model. The change in proportion of variance accounted for by adding light-intensity physical activity to the original model was 0.02, which was significant (F (1,834) = 11.75, p <0.001), suggesting light-intensity physical activity explained an additional 2% of the variance in depression scores. The change in variance accounted for by then adding moderate-intensity physical activity was not significant (R 2 < 0.001, F (1, 786) = 0.240, p = 0.625), while then adding strenuous physical activity to the model explained an additional 0.8% of the variance in depression scores, which was significant (R 2Δ = 0.008, F (1, 786) = 6.48, p = 0.012). The unstandardized regression coefficients (b), standard errors (SE b), standardized regression coefficients (β), additional variance explained (R 2Δ), and associated F-values for the full hierarchical regression analysis can be found in Table 3 . Both the light intensity and vigorous intensity subscales of the PASE contributed significantly to the explanation of depression symptoms, controlling for age, sex, and education. Although there were no issues of multicollinearity between the 3 physical activity intensity subscales, partial correlations were performed on the three intensity subscales, while controlling for age, sex, and education to determine the extent of shared variance between the light and moderate and moderate and vigorous subscales. These partial correlations revealed substantial overlap between the light and moderate subscales (r = 0.50, p <0.001), with less shared variance between the light and vigorous subscales (r = 0.09, p = 0.007) and moderate and vigorous subscales (r = 0.13, p ≤0.001).

TABLE 3.

Hierarchical Linear Regression Results for Light (Model 2), Moderate (Model 3), and Vigorous (Model 4) Intensity Physical Activity as Predictors of Depression Symptoms After First Controlling for Age, Sex, and Education (Model 1)

| Predictor Variable | Model 1 |

Model2 |

Model 3 |

Model 4 |

||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| b | SE b | β | b | SE b | β | b | SE b | β | b | SE b | β | |

| Sex (vs female) | −1.91 | 0.61 | −0.11b | −1.78 | 0.60 | −0.10b | −1.78 | 0.60 | −0.10b | −1.59 | 0.60 | −0.09b |

| Age (vs 50–59) | ||||||||||||

| 60–69 | −0.16 | 0.59 | −0.01 | −0.34 | 0.59 | −0.02 | −0.35 | 0.59 | −0.02 | −0.47 | 0.59 | −0.03 |

| 70–79 | −1.31 | 0.67 | −0.08 | −1.61 | 0.67 | −0.10a | −1.63 | 0.67 | −0.10a | −1.84 | 0.67 | −0.11b |

| 80–89 | −2.04 | 1.06 | −0.07 | −2.39 | 1.05 | −0.08a | −2.40 | 1.05 | −0.08a | −2.62 | 1.05 | −0.09a |

| 90+ | 3.85 | 3.20 | 0.04 | 3.56 | 3.17 | 0.03 | 3.54 | 3.17 | 0.04 | 3.47 | 3.16 | 0.04 |

| Education (vs college) | ||||||||||||

| Some HS | −3.12 | 2.29 | −0.04 | −3.36 | 2.27 | −0.05 | −3.35 | 2.27 | −0.05 | −3.34 | 2.26 | −0.05 |

| HS diploma/GED | 1.80 | 0.92 | −0.07 | 1.68 | 0.92 | 0.07 | 1.67 | 0.92 | 0.06 | 1.81 | 0.92 | 0.07a |

| Some college/vocation | 0.01 | 0.65 | 0.01 | −0.01 | 0.64 | −0.01 | −0.01 | 0.65 | −0.01 | 0.05 | 0.65 | 0.01 |

| Graduate | −1.20 | 0.67 | −0.07 | −1.21 | 0.67 | −0.07 | −1.21 | 0.68 | −0.07a | −1.13 | 0.67 | −0.07 |

| Doctorate | −0.09 | 0.90 | −0.01 | −0.18 | 0.89 | −0.01 | −0.18 | 0.89 | −0.01 | −0.10 | 0.89 | −0.01 |

| PASE subscales | ||||||||||||

| Light activity | −0.12 | 0.03 | −0.14c | −0.11 | 0.03 | −0.13c | −0.10 | 0.03 | −0.12b | |||

| Moderate activity | −0.02 | 0.04 | −0.02 | −0.01 | 0.04 | −0.01 | ||||||

| Vigorous activity | −0.07 | 0.03 | −0.09a | |||||||||

| R2 | 0.039 | 0.059 | 0.059 | 0.067 | ||||||||

| F for change in R2 | 17.36c | 0.24 | 6.48a | |||||||||

Notes: Nonstandardized and standardized beta coefficients are reported.

Referent education is college degree. Referent age is 50–59.

p <0.05.

p <0.01.

p <0.001.

CONCLUSIONS

The results from this cross-sectional study indicate that the well-established associations between higher levels of total physical activity and reduced symptoms of depression in older adults survive the COVID-19 pandemic. Specifically, we found that after controlling for age, sex, and education, a greater total amount of physical activity was associated with lower depression symptoms, but not anxiety-like symptoms. Furthermore, we found that the amount of both light and vigorous intensity activity made significant, unique contributions to overall depression scores. This finding suggests that higher levels of physical activity ranging from as little as light to as much as strenuous may help further alleviate some of the negative mental health symptoms experienced by older adults while SDG are followed during the COVID-19 pandemic.

The role of physical activity in mitigating depression symptoms in this sample of older adults is in line with previous studies on depression and physical activity that were conducted before the COVID-19 pandemic. De Mello et al (2013) surveyed over 1,000 adults and found that those who did not engage in physical activity were twice as likely to exhibit symptoms of depression and anxiety than individuals who performed physical activity regularly. Though the efficacy of exercise interventions for treating depression in older adults is still up for debate,14 observational studies indicate adults performing greater amounts of physical activity experience less anxiety and depression-like symptoms.19 , 33 Furthermore, the benefits of physical activity for depression symptoms were recently shown in a cohort of older adults.22 Of note, Mumba et al (2020) found that moderate and vigorous-intensity activity were significant and unique predictors of depression scores. Our findings add to this body of literature and suggest that both light and vigorous-intensity physical activity are significant and unique predictors of depression symptoms during the unique circumstance of a global pandemic. Under the constraints of SDG and stay-at-home orders, including the closures of gymnasiums and in person group exercise classes in many regions of the United States and Canada, opportunities for habitual activity may be compromised, whereas lighter intensity activity may be more accessible. The three physical activity intensity subscales did not show evidence of multicollinearity, but the light, moderate, and vigorous-intensity subscales were significantly associated with each other after controlling for covariates. The light and moderate-intensity subscales showed the highest correlation (r = 0.50), which was larger than the correlation between the light and vigorous (r = 0.09) and moderate and vigorous (r = 0.13) subscale scores. The strong association between light and moderate intensity subscales could potentially explain why light and strenuous, but not moderate-intensity activity, were related to depression symptoms. It is possible that individuals were not able to report differences between light and moderate-intensity physical activity accurately, or the scale did a poor job of distinguishing between light- and moderate-intensity physical activity. Because of the apparent shared variance between the light- and moderate-intensity scales in predicting depression symptoms, moderate intensity physical activity was unable to account for unique variance in depressive symptoms over and above light-intensity physical activity.

Interestingly, there was no significant relationship between physical activity levels and anxiety symptoms. Exercise and physical activity are believed to elicit anxiolytic benefits for adults,34 with previous observational studies showing an inverse relationship between the amount of physical activity performed and an individual's anxiety score.19 , 33 The discrepancy in these findings could be due to response bias in our sample, as 171 fewer participants had complete GAS scores than GDS scores due to missing/unanswered items on the scales. It is also possible that higher levels of physical activity do not attenuate symptoms of anxiety in older adults that are specific to the COVID-19 pandemic. Older adults are at greater risk for severe symptoms from COVID-19 and thus, fears associated with contracting the disease may be causing symptoms of anxiety in this older adult population that do not respond to being more physically active. Future work is needed to understand the factors related to anxiety symptoms under a global pandemic.

An additional question that could be asked is how COVID-19 has affected the physical activity behavior of older adults. Previous reports suggest the pandemic may cause many older adults to perform less physical activity17 , 18; however, empirical evidence is lacking. Our participants had an average score of 102.5 with a standard deviation of 63.8 on the PASE scale. Although we do not have pre-COVID data to compare the reported results to, a previous sample of 297 similarly aged (60–88 years) community-dwelling older adults residing in Canada were found to have an average score of 155 with a standard deviation of 66.35 Additionally, a previous study with 84 similarly aged older adults (55–87 years) who lived in the United States reported a mean PASE scale of 137.4 with a standard deviation of 55.7.36 While it is not possible to directly compare these pre-COVID results to the results in the current manuscript, they do suggest that respondents in our survey were performing less physical activity, which may have been the result of the pandemic. The results of our question asking participants to provide a subjective indication of how their physical activity behaviors have changed since the pandemic appears to corroborate the idea that these individuals are performing less physical activity, as 37.3% of participants indicated performing less physical activity since the onset of COVID-related SDG.. Future studies will need to use more objective measures to determine how the pandemic effected physical activity levels among older adults.

Exercise and physical activity are beneficial for both the mental and physical health of older adults, and recent commentaries have called for programs to help increase physical activity and exercise to ameliorate the negative psychological and physical consequences of the COVID-19 quarantine.18 , 37 Some of these commentaries have provided examples.37 , 38 This descriptive cross-sectional study is the first study to look at the association between physical activity levels and mental health symptoms in older adults during the COVID-19 pandemic. The strengths of this study are its moderately large sample that includes individuals from nearly every state in the United States and many provinces of Canada, and the use of well-established measures of physical activity and symptoms of anxiety and depression validated for use in older adults. However, our study also has several limitations. Survey respondents were predominantly well-educated, female, and white, and thus, one should use caution when trying to generalize these results to the general population. Although, 37% of our respondents reported a decrease in physical activity after COVID-19, we did not assess the impact of change in physical activity on our findings; which should be a topic of future investigation as we follow-up with the participants. Additionally, the cross-sectional nature of the study makes it impossible to determine causation. It is not possible to distinguish whether individuals who perform more physical activity experienced less depression-like symptoms, or if people who have a higher incidence of depression-like symptoms are less likely to perform physical activity. Finally, although we utilized measures of anxiety, depression and physical activity that have ample evidence for their validity in our sample demographic, it is unknown how their administration in an online format may affect these outcomes.

Given the increased degree of isolation experienced by older adults during the current pandemic, these individuals are at particularly higher risk of mental health problems associated with social isolation. Moreover, due to the possibility that many older adults may need to maintain isolation even as regions of the countries begin to ease stay-at-home orders, it is crucial to determine safe and healthy means by which older adults can maintain their mental health. Although these results are a promising start, future work will need to implement more objective measures of physical activity and explore the longitudinal effects that physical activity and the COVID-19 pandemic have on the mental health of older adults.

Author Contribution

D.C., N.A., J.C.S. conceived and planned the experiment. D.C., N.A., J.C.S, L.J., and G.P. helped develop and create the survey. D.C. analyzed the data with the help of J.W., J.C.S, and J.L.W. D.C wrote the manuscript with support from N.A., J.C.S., L.J., GP, J.W, and J.L.W.

Disclosure

This work was supported by the Department of Kinesiology and School of Public Health at the University of Maryland .

None of the authors have conflict of interests to report.

Footnotes

Supplementary material associated with this article can be found, in the online version, at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jagp.2020.06.024.

Appendix. SUPPLEMENTARY MATERIALS

References

- 1.Du RH, Liang LR, Yang CQ. Predictors of mortality for patients with COVID-19 pneumonia caused by SARS-CoV-2: a prospective cohort study. Eur Respir J. 2020;55(5) doi: 10.1183/13993003.00524-2020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Zhai P, Ding Y, Wu X. The epidemiology, diagnosis and treatment of COVID-19. Int J Antimicrob Agents. 2020 doi: 10.1016/j.ijantimicag.2020.105955. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Shahid Z, Kalayanamitra R, McClafferty B. COVID‐19 and older adults: what we know. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2020;68(5):926–929. doi: 10.1111/jgs.16472. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Wang L, He W, Yu X. Coronavirus disease 2019 in elderly patients: characteristics and prognostic factors based on 4-week follow-up. J Infect. 2020 doi: 10.1016/j.jinf.2020.03.019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.CDC, “Older adults,” 2020. [Online]. Available at:https://www.cdc.gov/coronavirus/2019-ncov/need-extra-precautions/older-adults.html. Accessed May 9, 2020.

- 6.Armitage R., Nellums L.B. COVID-19 and the consequences of isolating the elderly. Lancet Public Health. 2020;5(5):e256. doi: 10.1016/S2468-2667(20)30061-X. Elsevier Ltd, [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Umberson D., Karas Montez J. Social relationships and health: a flashpoint for health policy. J Health Soc Behav. 2010;51(1_suppl):S54–S66. doi: 10.1177/0022146510383501. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Cacioppo J.T., Hawkley L.C. Perceived social isolation and cognition. Trends Cogn Sci. 2009;13(10):447–454. doi: 10.1016/j.tics.2009.06.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Steptoe A., Shankar A., Demakakos P. Social isolation, loneliness, and all-cause mortality in older men and women. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2013;110(15):5797–5801. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1219686110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Santini ZI, Jose PE, Cornwell EY. Social disconnectedness, perceived isolation, and symptoms of depression and anxiety among older Americans (NSHAP): a longitudinal mediation analysis. The Lancet Public Health. 2020;5(1):e62–e70. doi: 10.1016/S2468-2667(19)30230-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Courtin E., Knapp M. Social isolation, loneliness and health in old age: a scoping review. Health Soc Care Community. 2017;25(3):799–812. doi: 10.1111/hsc.12311. Blackwell Publishing Ltd. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Shankar A., McMunn A., Banks J. Loneliness, social isolation, and behavioral and biological health indicators in older adults. Health Psychol. 2011;30(4):377–385. doi: 10.1037/a0022826. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Cardiovascular Health Study Collaborative Research Group. Fried LP, Kronmal RA, Newman AB. Risk factors for 5-year mortality in older adults: the Cardiovascular Health Study. JAMA. 1998;279(8):585–592. doi: 10.1001/jama.279.8.585. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Mura G., Carta M.G. Physical activity in depressed elderly. A systematic review. Clin Pract Epidemiol Ment Health. 2013;9(1):125–135. doi: 10.2174/1745017901309010125. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Woodard JL, Sugarman MA, Nielson KA, Smith JC, Seidenberg M, Durgerian S, Matthews MA, Rao SM. Lifestyle and genetic contributions to cognitive decline and hippocampal structure and function in healthy aging. Curr Alzheimer Res. 2012;9(4):436–446. doi: 10.2174/156720512800492477. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Schrempft S., Jackowska M., Hamer M. Associations between social isolation, loneliness, and objective physical activity in older men and women. BMC Public Health. 2019;19(1):74. doi: 10.1186/s12889-019-6424-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Jakobsson J., Malm C., Furberg M. Physical activity during the coronavirus (COVID-19) pandemic: prevention of a decline in metabolic and immunological functions. Front Sport Act Living. 2020;2:57. doi: 10.3389/fspor.2020.00057. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Jiménez-Pavón D, Carbonell-Baeza A, Lavie CJ. Physical exercise as therapy to fight against the mental and physical consequences of COVID-19 quarantine: special focus in older people. Prog Cardiovasc Dis. 2020 doi: 10.1016/j.pcad.2020.03.009. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC7118448/ Ahead of print. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Da Silva MA. Bidirectional association between physical activity and symptoms of anxiety and depression: the Whitehall II study. Eur J Epidemiol. 2012;27(7):537–546. doi: 10.1007/s10654-012-9692-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hamer M., Stamatakis E., Steptoe A. Dose-response relationship between physical activity and mental health: the Scottish health survey. Br J Sports Med. 2009;43(14):1111–1114. doi: 10.1136/bjsm.2008.046243. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Asztalos M., De Bourdeaudhuij I., Cardon G. The relationship between physical activity and mental health varies across activity intensity levels and dimensions of mental health among women and men. Public Health Nutr. 2010;13(8):1207–1214. doi: 10.1017/S1368980009992825. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Mumba MN, Nacarrow AF, Cody S. Intensity and type of physical activity predicts depression in older adults. Aging Ment Health. 2020:1–8. doi: 10.1080/13607863.2020.1711861. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Brenes GA, Williamson JD, Messier SP. Treatment of minor depression in older adults: a pilot study comparing sertraline and exercise. Aging Ment Health. 2007;11(1):61–68. doi: 10.1080/13607860600736372. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Herring M.P., Jacob M.L., Suveg C. Feasibility of exercise training for the short-term treatment of generalized anxiety disorder: a randomized controlled trial. Psychother Psychosom. Dec. 2011;81(1):21–28. doi: 10.1159/000327898. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Mather A.S., Rodriguez C., Guthrie M.F. Effects of exercise on depressive symptoms in older adults with poorly responsive depressive disorder. Br J Psychiatry. 2002;180:411–415. doi: 10.1192/bjp.180.5.411. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Merom D. Promoting walking as an adjunct intervention to group cognitive behavioral therapy for anxiety disorders-a pilot group randomized trial. J Anxiety Disord. 2008;22(6):959–968. doi: 10.1016/j.janxdis.2007.09.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Mota-Pereira J., Silverio J., Carvalho S. Moderate exercise improves depression parameters in treatment-resistant patients with major depressive disorder. J Psychiatr Res. 2011;45(8):1005–1011. doi: 10.1016/j.jpsychires.2011.02.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Siordia C. Alternative scoring for physical activity scale for the elderly (PASE) Maturitas. 2012;72(4):379–382. doi: 10.1016/j.maturitas.2012.05.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Washburn R.A., Smith K.W., Jette A.M. The physical activity scale for the elderly (PASE): development and evaluation. J Clin Epidemiol. 1993;46(2):153–162. doi: 10.1016/0895-4356(93)90053-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Yesavage JA, Brink TL, Rose TL. Development and validation of a geriatric depression screening scale: a preliminary report. J Psychiatr Res. 1982;17(1):37–49. doi: 10.1016/0022-3956(82)90033-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Segal D.L., June A., Payne M. Development and initial validation of a self-report assessment tool for anxiety among older adults: the geriatric anxiety scale. J Anxiety Disord. 2010;24(7):709–714. doi: 10.1016/j.janxdis.2010.05.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.R Core Team . 2018. R: A Language and Environment for Statistical Computing. Vienna, Austria. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Teixeira C.M., Vasconcelos-Raposo J., Fernandes H.M. Physical activity, depression and anxiety among the elderly. Soc Indic Res. 2013;113(1):307–318. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Anderson EH, Shivakumar G. Effects of exercise and physical activity on anxiety. Front Psychiatr. 2013;4:27. doi: 10.3389/fpsyt.2013.00027. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Logan S.L., Gottlieb B.H., Maitl S.B. The physical activity scale for the elderly (PASE) questionnaire; does it predict physical health? Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2013;10(9):3967–3986. doi: 10.3390/ijerph10093967. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Sink KM, Espeland MA, Castro CM. Effect of a 24-month physical activity intervention vs health education on cognitive outcomes in sedentary older adults: the LIFE randomized trial. JAMA. 2015;314(8):781–790. doi: 10.1001/jama.2015.9617. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Chen P., Mao L., Nassis G.P. Wuhan coronavirus (2019-nCoV): the need to maintain regular physical activity while taking precautions. J Sport Health Sci. 2020;9(2):103–104. doi: 10.1016/j.jshs.2020.02.001. Elsevier B.V. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.ACSM . 2020. Staying Active During the Coronavirus Pandemic. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.