The coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) pandemic has abruptly reduced gastrointestinal endoscopy activity worldwide. This has had a consequent impact on endoscopy training in the United Kingdom (UK). However, the impact on trainee procedure exposure has not been quantified. We conducted a UK-wide survey with the aim of quantifying the impact of COVID-19 on hands-on endoscopy procedures performed by trainees and on their emotional well-being.

Methods

A 37-item survey (Supplementary File) was developed as part of an international collaborative (EndoTrain).1 The survey was endorsed and disseminated to UK trainees by the British Society of Gastroenterology (BSG) and was open for a 3-week period (April 11–May 2, 2020). The primary outcome measured was the reduction in 30-day volume of hands-on endoscopy procedures during COVID (ie, 30-days leading up the survey) vs the average month before COVID-19. Endoscopic methods studied comprised esophagogastroduodenoscopy, colonoscopy, endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography, endoscopic ultrasound, and upper gastrointestinal bleeding, which was included within the esophagogastroduodenoscopy numbers. These were measured for supervised, independent (unsupervised), and total numbers. Secondary outcomes comprised rates of anxiety, measured using the Generalized Anxiety Disorder-7 tool,2 burnout, and uptake of alternative training resources. For each endoscopic method, respondents who recorded 0 procedures over their pre–COVID-19 period were excluded to limit analyses to actively participating trainees.

Comparisons over two 30-day time periods were made using Wilcoxon’s signed rank tests and across methods modalities using Kruskal-Wallis with multiple comparisons Dunn’s tests. Statistical analyses were performed using SPSS 26 software (IBM Corp, Armonk, NY), with significance at P < .05.

Results

Respondents

The survey was completed by 132 respondents from the specialties of gastroenterology (101 [76.5%]), surgery (24 [18.2%]), and pediatric gastroenterology (7 [5.3%]). Trainees had received a median of 3 years of training (interquartile range, 1-5 years). The response rate of gastroenterology trainees was approximately 20%, and 53% of trainees performed ≥1 procedures without supervision.

Impact of COVID-19 on Trainee Procedures

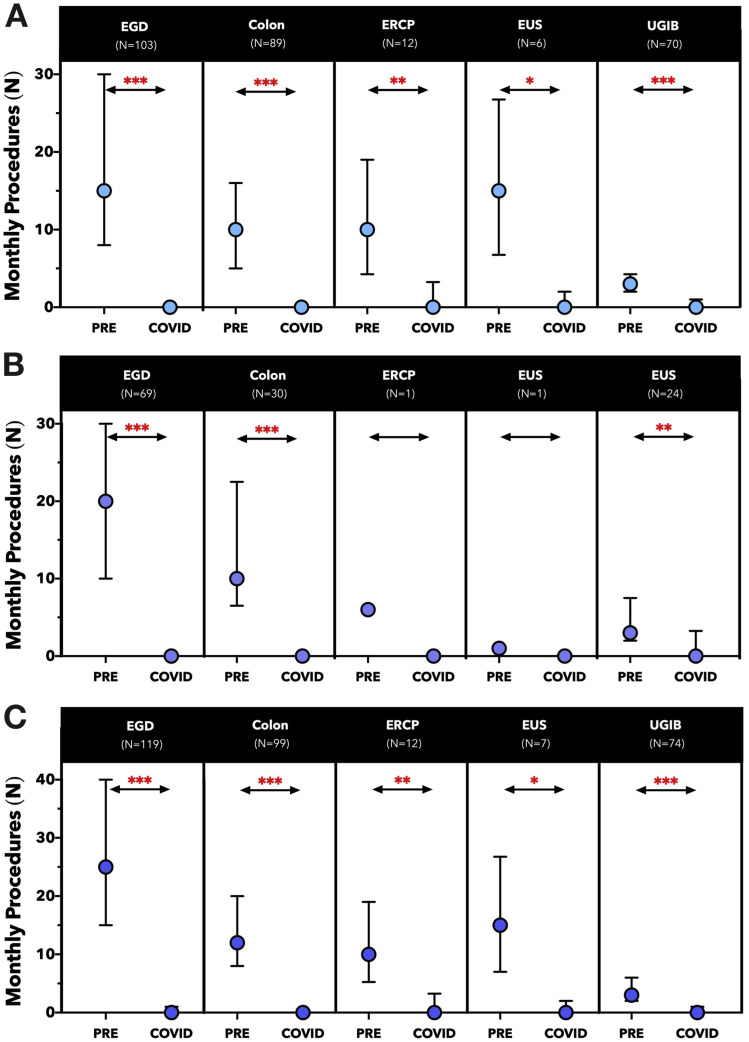

All active trainees reported a reduction in monthly endoscopy volume due to COVID-19. For each method, there was a significant decrease (P < .001) in average monthly numbers of supervised and unsupervised hands-on procedures before and during COVID-19 (Figure 1 ). The mean percentage reductions for supervised, unsupervised, and all trainee procedures were 93.5% (SD, 23.6%), 96.3% (SD, 12.1%), and 96.0% (SD, 12.8%), respectively. This percentage reduction did not differ by level of supervision (P = .781) or specialty (P = .108), but varied across methods (P = .001), with a significant difference (P < .001) between upper gastrointestinal bleeding procedures (mean reduction, 78%; SD, 43.9%) and colonoscopy (mean reduction, 97.2%; SD, 12.4%).

Figure 1.

Comparison of trainee-reported number of (A) supervised procedures, (B) independent procedures, and (C) total procedures in the 30-day period pre (PRE) and during COVID-19 (COVID). Symbols and error bars represent the median and interquartile ranges. ∗P < .05, ∗∗P < .001, ∗∗∗P < .0001. Colon, colonoscopy; EGD, esophagogastroduodenoscopy; ERCP, endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography; EUS, endoscopic ultrasound; n, number of actively participating trainees; UGIB, upper gastrointestinal bleeding hemostasis.

Barriers to Training

The reasons cited for the reduction in opportunities comprised changes to institutional policy that excluded trainees from procedures (75.8%), lack of cases (56.8%), and redeployment to another clinical area (47.7%). Endoscopy training remained accessible on an ad hoc basis to 69.7%. Reductions in institutional endoscopy case volume were reported by 100%, with 96.0% reporting reductions in excess of 50%. Altogether, 21.2% (n = 28) of trainees were on an emergency endoscopy rota before COVID-19. Participation was stopped or reduced in frequency in 71.4% (n = 20).

Trainees’ Concerns

Competency development was a concern for 93.4% (n = 113) of trainees, and 82.6% (n = 100) were concerned with the possible need to prolong speciality training due to COVID-19. Modification of existing UK guidelines to support endoscopy training was endorsed by 56.7% (n = 68).

Anxiety and burnout were assessed in 120 trainees. Of these, 50% had anxiety based on Generalized Anxiety Disorder-7 criteria (35.8% mild, 9.2% moderate, and 5.0% severe), with 10.8% meeting criteria for burnout. Institutional provision of emotional support strategies during the COVID-19 pandemic was available to 90.8% of trainees.

Alternate Sources of Education

During the COVID-19 pandemic, 37.5% (n = 45) did not access any alternate educational resources for endoscopy training. At least weekly use was reported for social media-based education (29.1%), followed by endoscopy journals (15.8%), online courses from gastrointestinal societies (15.0%), and distant learning from institutions (9.2%).

Discussion

The COVID-19 pandemic has adversely affected endoscopy trainees in the UK, with a mean reduction in procedure count of 96.0%. This was mainly due to changes to institutional policies limiting trainee access, reduction in unit case volumes, and redeployment toward high-priority clinical areas. Such disruptions have led to concerns regarding competency development and the prolongation of training to achieve competence, which may be fuelling anxiety and burnout during this period.

Our survey had several limitations. Our survey had a response rate of 20%, a dropout rate of 9%, and did not include nurse endoscopist trainees. Regional data and lifetime procedural counts were not collected. The survey was a snapshot taken during the acceleration phase of COVID-19 and did not provide a dynamic assessment of procedural data in line with COVID-19 caseload. National Endoscopy Databases could be interrogated in the future for this purpose.3

Like many countries, the UK places reliance on minimum procedure numbers as a competency safeguard. These are embedded within national certification processes for independent practice overseen by the Joint Advisory Group.4 The effects of COVID-19 are projected to persist until 2022,5 coinciding with UK Shape of Training reforms aimed at reducing specialty training from 5 to 4 years.6 This combination is likely to render minimum procedure numbers unattainable for many trainees. In response, the BSG is actively engaging in multistakeholder dialogue to discuss possible solutions:

First, learning curves for cognitive skills could be optimized by increasing access to hands-off training methods, including alternative educational-based training,7 while promoting access to ad hoc hands-on opportunities.

Second, summative evaluation could focus less on minimum numbers and more on validated competency assessment tools,8 , 9 with consideration for distant assessment to conserve personal protective equipment.

Third, a defined period of mentorship could be adopted for those who complete specialist training without acquiring certification.

Finally, trainee well-being will also be prioritized on the BSG agenda. We hope that these measures can be incorporated with solutions from other societies to help provide much needed support to endoscopy trainees nationwide.7

Acknowledgments

CRediT Authorship Contributions analysis

Keith Siau, MBChB, MRCP (Conceptualization: Equal; Data curation: Equal; Formal Lead; Methodology: Equal; Project administration: Equal; Supervision: Lead; Validation: Equal; Visualization: Equal; Writing – original draft: Equal; Writing – review & editing: Equal). Marietta Iacucci, MD, PhD, FASGE, FRCPE (Supervision: Equal; Writing – review & editing: Equal). Paul Dunckley, DPhil, FRCP (Supervision: Equal; Writing – review & editing: Equal). Ian Penman, FRCP (Supervision: Equal; Writing – review & editing: Equal).

Footnotes

Conflicts of interest The authors disclose no conflicts.

Note: To access the supplementary material accompanying this article, visit the online version of Gastroenterology at www.gastrojournal.org, and at https://doi.org/10.1053/j.gastro.2020.06.015

Contributor Information

EndoTrain Survey Collaborators:

Katarzyna M. Pawlak, Jan Kral, Rishad Khan, Sunil Amin, Mohammad Bilal, Rashid N. Lui, Dalbir S. Sandhu, Almoutaz Hashim, ABIM Steven Bollipo, Aline Charabaty, Enrique de-Madaria, Andrés Felipe Rodríguez-Parra, Sergio A. Sánchez-Luna, Michał Żorniak, Catharine M. Walsh, and Samir C. Grover

Appendix

EndoTrain Collaborators

Katarzyna M. Pawlak, MD, PhD, Hospital of the Ministry of Interior and Administration, Szczecin, Poland; pawlakatarzyna@gmail.com. Jan Kral, MD, Institution for Clinical and Experimental Medicine, Prague, Czech Republic; jan.kral@ikem.cz. Rishad Khan, MD, Department of Medicine, University of Toronto, Toronto, Ontario, Canada; rishad.khan@mail.utoronto.ca. Sunil Amin, MD, MPH, Division of Digestive Health and Liver Diseases, Department of Medicine, University of Miami Miller School of Medicine, Miami, Florida; sunil.amin@med.miami.edu. Mohammad Bilal, MD, Division of Gastroenterology & Hepatology, Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center, Harvard Medical School, Boston, Massachusetts; billa17@hotmail.com. Rashid N. Lui, MBChB, MRCP, Division of Gastroenterology and Hepatology and Institute of Digestive Disease, The Chinese University of Hong Kong, Hong Kong, China; rashidlui@cuhk.edu.hk. Dalbir S. Sandhu, MD, Director of Endoscopy, Cleveland Clinic Akron General, Assistant Professor of Medicine-Case Western Reserve University, Division of Gastroenterology, Hepatology & Nutrition, Cleveland Clinic, Cleveland, Ohio; drdalbir@gmail.com. Almoutaz Hashim, MD, FRCPC, ABIM Vice Dean of Academic Affairs-Assistant Professor of Medicine at The University of Jeddah, Jeddah, Saudi Arabia; ahahshem@uj.edu.sa. Steven Bollipo, FRACP, Director of Gastroenterology & Endoscopy, John Hunter Hospital, and University of Newcastle, Newcastle, Australia; steven.bollipo@newcastle.edu.au. Aline Charabaty, MD, AGAF, Division of Gastroenterology, Johns Hopkins School of Medicine, Johns Hopkins-Sibley Memorial Hospital, Washington DC; acharab1@jhmi.edu. Enrique de-Madaria, MD, Gastroenterology Department, Alicante University General Hospital, Alicante Institute for Health and Biomedical Research (ISABIAL), Alicante, Spain; madaria@hotmail.com. Andrés Felipe Rodríguez-Parra, MD, General Hospital Dr. Manuel Gea González, National Autonomous University of Mexico; Mexico City, Mexico; andresrodriguezparra@gmail.com. Sergio A. Sánchez-Luna, MD, Division of Gastroenterology and Hepatology, The University of New Mexico School of Medicine, Albuquerque, New Mexico; ssanchezluna@gmail.com. Michał Żorniak, MD; Department of Gastroenterology, Medical University of Silesia, Katowice, Poland; mzorniak@sum.edu.pl. Catharine M. Walsh, MD, MEd, PhD, Division of Gastroenterology, Hepatology and Nutrition and the Research and Learning Institutes, Hospital for Sick Children, Department of Paediatrics and the Wilson Centre, University of Toronto, Toronto, Ontario, Canada; catharine.walsh@utoronto.ca. Samir C. Grover, MD, MEd, FRCPC, AGAF, Department of Medicine, University of Toronto, Li Ka Shing Knowledge Institute, St. Michael’s Hospital, and Division of Gastroenterology, University of Toronto, Toronto, Ontario, Canada; samir.grover@utoronto.ca.

Supplementary Material

The International Endoscopy Training (EndoTrain) Survey

-

ADemographics

-

1.What is your age (optional - numerical box)

-

2.Your gender (optional)

-

a.Female

-

b.Male

-

c.Other (free text option)

-

a.

-

3.Country of training

-

4.What specialty are you in?

-

a.Adult gastroenterology

-

b.Pediatric gastroenterology

-

c.Surgery

-

d.Internal medicine

-

e.Other (free text option)

-

a.

-

5.Number of years in endoscopy training (numerical box)

-

6.Are you currently doing an advanced endoscopy fellowship? YES/NO

-

7.What is the focus of your endoscopy training program? (Tick all that apply)

-

a.Upper GI

-

b.Lower GI

-

c.ERCP

-

d.EUS

-

e.Other (free text)

-

a.

-

1.

-

BEndoscopy

-

8.Prior to the COVID-19 pandemic, approximately how many procedures would you perform each month under supervision for the following:

-

a.EGD/OGD

-

b.Colonoscopy

-

c.ERCP

-

d.EUS

-

e.Therapy for Upper GI bleed

-

a.

-

9.Prior to the COVID-19 pandemic, approximately how many procedures would you perform each month independently (without supervision within the room) for the following: (numerical box, default value set at 0)

-

a.EGD/OGD

-

b.Colonoscopy

-

c.ERCP

-

d.EUS

-

e.Therapy for Upper GI bleed

-

a.

-

10.Has your exposure to endoscopy cases decreased during the COVID-19 pandemic?

-

a.YES (if Yes, please indicate the reason(s) for decreased endoscopy case volume- tick all that apply)

-

i.Lack of cases

-

ii.Lack of PPE availability

-

iii.Personal decision

-

iv.Institutional policy

-

v.Redeployed to another clinical area

-

vi.Other (specify [free text comment])

-

i.

-

b.NO

-

a.

-

11.Which endoscopy opportunities still remain for you? (tick all that applies)

-

a.None (not performing endoscopy)

-

b.No restrictions

-

c.Only procedures which I can perform without supervision

-

d.Only patients at low-risk/negative for COVID-19

-

e.ICU cases

-

f.Emergency cases

-

g.Other (free text comment)

-

a.

-

12.Prior to the COVID-19 pandemic, did you participate in an emergency (on-call) endoscopy rota/schedule?

-

a.YES – If Yes, since COVID-19, has this:

-

i.Stopped

-

ii.Reduced in frequency

-

iii.Remain unchanged

-

i.

-

b.NO

-

a.

-

13.How has your institution’s case volume been affected by the COVID-19 pandemic?

-

a.Not affected

-

b.Yes, but don’t know

-

c.Decreased by 1-25%

-

d.Decreased by 26-50%

-

e.Decreased by 51-75%

-

f.Decreased by 76-99%

-

g.Decreased by 100% (no endoscopy being performed at all)

-

a.

-

14.During the COVID-19 pandemic, approximately how many procedures are you performing each month under supervision for the following: (numerical box, default value set at 0)

-

a.EGD/OGD

-

b.Colonoscopy

-

c.ERCP

-

d.EUS

-

e.Therapy for Upper GI bleed

-

a.

-

15.During the COVID-19 pandemic, approximately how many procedures are you performing each month independently for the following: (numerical box, default value set at 0)

-

a.EGD/OGD

-

b.Colonoscopy

-

c.ERCP

-

d.EUS

-

e.Therapy for Upper GI bleed

-

a.

-

8.

-

CPPE

-

16.Have you received any training on appropriate use of PPE for COVID-19 patients?

-

a.YES

-

b.NO

-

a.

-

17.Have you received any training on how to manage a COVID-19 patient in your endoscopy unit?

-

a.YES

-

i.In person

-

ii.By virtual meeting

-

iii.By written communication

-

i.

-

b.NO

-

a.

-

18.Do you feel that the level of PPE used in your endoscopy unit during the COVID-19 pandemic is adequate?

-

a.YES

-

b.NO

-

a.

-

19.Has your institution restricted endoscopy volume because of insufficient PPE?

-

a.YES

-

b.NO

-

a.

-

20.Does your endoscopy unit follow guidelines for protection against COVID-19?

-

a.YES (pick one)

-

i.National

-

ii.Societal

-

iii.Hospital’s own recommendations

-

i.

-

b.NO

-

a.

-

16.

-

DWell Being

-

21.Have you taken time off work because of confirmed or suspected COVID-19?

-

a.YES

-

i.For myself

-

ii.For a household member

-

i.

-

b.NO

-

a.

-

22.Have you tested positive for COVID-19?

-

a.YES

-

b.NO

-

c.Not tested

-

d.Prefer not to answer

-

a.

-

23.How concerned are you about COVID-19 exposure during your current endoscopy training?

-

a.Not concerned

-

b.Slightly concerned

-

c.Moderately concerned

-

d.Extremely concerned

-

e.N/A (not training)

-

a.

-

24.How concerned are you that the COVID-19 pandemic is going to affect your competency in performing endoscopy?

-

a.Not concerned

-

b.Slightly concerned

-

c.Moderately concerned

-

d.Extremely concerned

-

a.

-

25.Are you concerned that the impact of COVID-19 on endoscopy training may prolong your fellowship/specialty training?

-

a.Not concerned

-

b.Slightly concerned

-

c.Moderately concerned

-

d.Extremely concerned

-

a.

-

26.Over the last 2 weeks, how often have you been affected by the following: (responses: Not at all, Several days, Over half of the days, Nearly every day)

-

a.Feeling nervous, anxious or on edge

-

b.Not being able to stop or control worrying

-

c.Worrying too much about different things

-

d.Trouble relaxing

-

e.Being so restless that it is hard to sit still

-

f.Becoming easily annoyed or irritable

-

g.Feeling afraid as if something awful might happen

-

h.Feeling loss of control

-

i.Not being able to focus on work

-

j.Anxiety of yourself or a loved one getting ill from COVID-19

-

a.

-

27.During this COVID-19 pandemic, how difficult is it for you to be yourself with others?

-

a.Not difficult at all

-

b.Somewhat difficult

-

c.Very difficult

-

d.Extremely difficult

-

a.

-

28.Overall, how would you rate your level of burnout? (select the most appropriate statement)

-

a.I enjoy my work and have no symptoms of burnout

-

b.Occasionally I am under stress, and I don’t always have as much energy as I once did, but don’t feel burned out

-

c.I am definitely burning out and have one or more symptoms of burnout, such as physical and emotional exhaustion

-

d.The symptoms of burnout that I’m experiencing won’t go away. I think about frustration at work a lot

-

e.I feel completely burned out and often wonder if I can go on. I am at the point where I may need some changes or may need to seek some sort of help

-

a.

-

29.Is your institution/program offering emotional or mental health support during these times?

-

a.Yes

-

i.Formal group or individual session

-

ii.Drop-in sessions

-

iii.Yes, but did not access

-

i.

-

b.No

-

a.

-

21.

-

EEducation

-

30.If the COVID-19 pandemic has impacted your hands-on endoscopy training, what additional training have you undertaken to supplement your endoscopy education? (responses: 1) Have not used, 2) 1-2 times in the last month, 3) Weekly, 4) 1-2 times per week, 5) 3-5 times per week, 6) Daily)

-

a.Physically attending organized teaching from your institution

-

b.Distance learning from your institution

-

c.Online courses from national/international societies

-

d.Social media education

-

e.Endoscopy journals (including electronic)

-

f.Webinars

-

g.Other (free text)

-

a.

-

31.Do you believe that your national/societal guidelines should be modified to support endoscopy training during COVID-19?

-

a.Yes (please feel free to comment -option for free text)

-

b.No

-

a.

-

32.Do you have any additional comments or suggestions on how to improve training during the COVID-19 pandemic? (optional)

-

30.

References

- 1.Pawlak K.M. Gastrointest Endosc. 2020;92:925–935. doi: 10.1016/j.gie.2020.06.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Spitzer R.L. Arch Intern Med. 2006;166:1092–1097. doi: 10.1001/archinte.166.10.1092. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Lee T.J. United European Gastroenterol J. 2019;7:798–806. doi: 10.1177/2050640619841539. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Siau K. Frontline Gastroenterol. 2019;10:93–106. doi: 10.1136/flgastro-2018-100969. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kissler S.M. Science. 2020;368(6493):860–868. doi: 10.1126/science.abb5793. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Clough J. Frontline Gastroenterol. 2019;10:356–363. doi: 10.1136/flgastro-2018-101168. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Keswani R.N. Gastroenterology. 2020;159(1):26–29. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2020.05.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Siau K. Endoscopy. 2018;50:770–778. doi: 10.1055/a-0576-6667. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Siau K. Am J Gastroenterol. 2020;115:234–243. doi: 10.14309/ajg.0000000000000426. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]