Abstract

This paper discusses the measures adopted by the Italian government to face the COVID-19 emergency after the first wave in March/April 2020. This study places these measures in light of the massive reform process based on the “managerialism” of healthcare, which started in the 1990s. These reforms, which were inspired by the ideas of ‘New Public Management’, introduced managerialism, regionalization and quasi-markets to the Italian National Health System. As a result, dramatic changes have been made in public healthcare, and the responsibility for healthcare was decentralized to regions, introducing a multi-level governance structure. The COVID-19 emergency has drawn the results of this approach into question. With the enactment of new decrees, the central government directly intervened in the management of the health system by introducing specific measures aiming to increase the number of hospital beds and personnel, which w previously downsized. We describe the main content of the new measures adopted to face the COVID-19 emergency and discuss how key points of the managerialization process in Italy are being questioned as a result of these measures. The COVID-19 emergency will likely redesign the trajectory of health reforms in Italy and other countries in Europe.

Keywords: COVID-19, Health managerialization, Health decentralization, New Italian decree, Health system capacity

1. Introduction

In December 2019, an outbreak of the novel coronavirus disease (COVID-19) in Wuhan, China, began to rapidly spread worldwide; on March 11, 2020, the World Health Organization declared a pandemic emergency.

A major consequence of the rapid spread of the virus was the overloading of hospitals, particularly infectious disease (IDU), pneumology (PU) and intensive care (ICU) units. The 2019-nCoV infection caused clusters of severe respiratory illness similar to severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus that were associated with ICU admission, mechanical ventilation and high mortality among older patients and those with medical comorbidities.

Hence, there was a need to implement urgent measures to provide assistance to a large number of patients [1]; most countries were not prepared to face this health emergency given the lack of human and structural resources.

This paper focuses on the experience of the Italian National Health Service (INHS) during the COVID-19 emergency. The outbreak of COVID-19 in Italy started on 31 January 2020 with two cases imported from China. On February 21, the first Italian citizen with COVID-19 was confirmed as follows [1]: “the country has been hit by nothing short of a tsunami of unprecedented force, punctuated by an incessant stream of deaths. It is unquestionably Italy’s biggest crisis since World War II” [2].

In February 2020, the Italian central government introduced measures initially intended for the red zone regions that were then gradually extended to the entire national territory.

Italy could be used as a case study considering that similar to many other countries, it underwent a massive process of reform based on the “managerialism” of healthcare. Consequently, a) dramatic changes have been made in public healthcare, with a significant reduction in beds and health personnel; b) the responsibilities for healthcare were decentralized to regions, although the central government still retains a key role in ensuring that all citizens have uniform access to health services throughout the country; and c) the autonomy of the regions in the organization of health services generated various approaches in local health systems, one for each different Italian region, and some emphasized offering hospital services, while others focused more on primary care. Therefore, profound differences in health outcomes are observed across regions in terms of the accessibility and appropriateness of care [3,4].

The COVID-19 emergency has completely overthrown this approach, leading to the questioning of the measures adopted over the last 30 years. With the enactment of several decrees, the central government introduced specific measures with a direct impact on the healthcare system and hospital management. The adopted measures aimed to increase the Italian health system capacity, which has been deeply downsized as a result of the reforms inspired by managerialism.

The case of Italy may provide useful evidence concerning the debate regarding the managerialization and decentralization of healthcare [1].

In this paper we describe the main content of the new measures adopted to face the COVID-19 emergency and discuss how key points of the managerialization process in Italy are being questioned.

2. Policy background: the INHS capacity

Starting in the 1990s, during the main wave of the international New Public Management movement [5], a series of reforms introducing managerialism, regionalization and quasi-markets was implemented as follows [6]: the central government maintained a guiding role in defining and controlling health outcomes and the financial sustainability of health care expenditures, while fiscally autonomous and financially responsible regions developed their own plans to achieve the health objectives defined by the central government [3].

The reforms in the 1990s were important and ground-breaking and followed a similar agenda in most European countries as follows [7,8]:

-

a)

A decentralization process from the national to regional and local levels introducing a multi-level governance structure with the following twofold aim: increase efficiency and improve the financial responsiveness of decentralized authorities [[9], [10], [11]];

-

b)

Organizational structure changes and implementation of personnel policies to reduce costs and rationalize public health;

-

c)

Governance structure changes in the delivery of health care by introducing a competitive logic between public and private providers;

-

d)

Introduction of various forms of performance-related payment systems to achieve the following three different objectives [12,13]: reduce costs, increase benefits, and increase the quality of healthcare systems; and

-

e)

Introduction of planning, accounting and control measures to achieve the transition from traditional cash introduction cash-based budgetary accounting to accruals accounting and the adoption of managerial accounting [8].

Currently, Italy is facing the following two major challenges: containing health system spending without reducing the healthcare quality and reducing regional differences in delivery by giving central authorities a greater role in supporting the regional monitoring of local performance [14].

Indeed, the process of devolving healthcare from the central government to regions that began in 2001 with the transfer of major fiscal, financial and managerial responsibilities to the regional level produced mixed results.

The inequality in population health outcomes and accessibility to services associated with the concerns regarding the financial sustainability of healthcare systems pushed several regions towards a re-centralization process, which was essentially implemented through the following tools:

-

1

The appointment of a Commissioner ad acta in regions that are unable to guarantee the services outlined in the Essential Levels of Care (LEAs), which is the basic benefits package that must be provided uniformly across the country;

-

2

The adoption of regional recovery plans (RRPs) aiming to reduce healthcare expenditures; and

-

3

The adoption of hospital recovery plans for monitoring trends in healthcare expenditures of individual hospitals and implementing vigorous and effective interventions to improve the care provided and ensure that all hospitals provide at last the LEAs.

Many national and regional databases have been implemented to monitor the healthcare quality and outcomes across the country. In addition to the detection system based on the LEA, the Agenzia Nazionale per i Servizi Sanitari Regionali (National Agency for Regional Health Services) implemented the Programma Nazionale Esiti (PNE - National Outcomes Programme), which covers nearly 129 indicators, including both process and clinical outcome measures, that are disaggregated at the municipal and hospital levels. In addition, there are numerous local patient registers, most of which are operated by professional and scientific societies.

2.1. INHS capacity

In this paper, we define the health system’s capacity in terms of the number of hospital beds and physicians.

Countries and regions that invest in more physicians and hospital beds provide more care and intensive treatments to their residents [15,16]. Indeed, recent studies have shown that during the first phase of the Covid-19 pandemic, in the absence of targeted therapeutic drugs, some important benefits may arise from enacting these investments [17], even if high capacity is excessive under normal conditions [18].

In Italy, the health system capacity and consequent responses to the pandemic were influenced by a combination of measures adopted to achieve the following:

-

•

a competitive logic between public and private providers;

-

•

organizational structure changes involving available beds and personnel policies; and

-

•

the devolution of healthcare from the central government to regions.

The reform in the 1990s recognized patients’ freedom of choice of providers, giving parity of treatment to public and private accredited providers [19,8]. Additionally, legislation encouraged public providers to establish partnerships with private organizations for the provision of core services.

The effect is a disempowerment of public hospitals, with the loss of thousands of public beds, in favour of private providers.

The de-hospitalization of Italian healthcare has progressed over time; the Law 135 of 07/08/2012 identified a target of 3.7 beds per 1000 inhabitants, of which 0.7 are designated non-acute. Aiming to introduce measures to contain public expenditures, the law identified measures that could allow the rationalization of public health expenditures and improve outcomes. This reduction applied to public hospitals for a share of not less than 50 % to be achieved through the elimination of Complex Operating Units; the aim was to achieve a hospitalization rate of 160 hospitalizations per 1000 inhabitants, of which at least 25 % occurred in a day hospital. Subsequently, the Health Pact 2014–2016 [20] and the national regulation on hospital standards (Health Minister Decree, n. 70/2015) confirmed the previous guidelines for hospital offerings.

In 2017, the national average endowment of beds - for both ordinary and diurnal hospital stays - amounted to 2.9 per thousand inhabitants for acute and 0.6 for non-acute. Only seven regions, all of which are located in northern Italy, except for Molise, have an overall endowment of beds higher than 3.7 [21].

Personnel policies were also significantly affected by the managerial reforms started in the 1990s in terms of both the introduction of new payment and incentive systems and the redefinition of needs. The most incisive intervention, which implemented downsizing policies of personnel in the Italian public sector, is the 2010 Finance Law [22], which provided a spending ceiling for personnel that cannot exceed the 2004 levels decreased by 1.4 %. During the 2010–2017 period, there was a marked contraction trend equal to 5.8 percentage points overall in all roles as follows: doctors (-5.4 %), healthcare roles (4.3 %) and other staff (-9.1 %) [21].

As a result of the managerialism reform, compared to the EU averages, the INHS is currently characterized by a decreasing use of hospitals (in terms of hospital beds, length of stay and admissions) without ensuring a proper professional case mix to manage chronic conditions [23].

Similar to many OECD countries, Italy currently faces a demographic and epidemiological shift with a growing ageing population and a rising burden of chronic conditions. However, comparative data strongly indicate that community, long-term care and preventive services are underdeveloped in Italy compared to those in other OECD countries [14].

As previously noted, the INHS capacity varies within the country. The adoption of such an extraordinary measure produced a reduction in not only healthcare spending but also hospital beds and health personnel, particularly in RRP regions, where personnel turnover was blocked by the central government [3,24].

The differences among the regions concern not only the capacity of the health system but also, more importantly, the management model of territorial medicine which should have included the treatment of many diseases previously treated in a hospital with territorial assistance.

Primary care assistance has been deeply affected by regionalism as each region defined its own primary care settings. Some regions created new organizational models based on the integration of different professionals (e.g., GPs, paediatricians, off-hours physicians, nurses, administrative personnel, etc.) working together to improve accessibility, equity and continuity of care for patients. Other regions have not been able to build a good primary care network and failed to achieve the minimum levels of assistance for primary care [23].

The differences in the health system among regions emerged in the management models of COVID-19. Some regions (such as Lombardy) adopted the in-hospital management of Covid-19 positive patients; other regions (such as Emilia Romagna) preferred to care for patients positive for COVID-19 at home, thus also avoiding infection among health workers [25]. Furthermore, other regions (such as Veneto) adopted a territorial or out-of-hospital model of management by increasing the number of swab tests among the population to achieve as many diagnoses as possible, promptly quarantine, treat infected patients early and reduce hospital admissions [26].

3. Content of the new policy

A major consequence of this emergency is the overloading of regional hospital structures, particularly ICUs, IDUs and PUs.

Therefore, in March 2020, the central government was forced to introduce extraordinary and urgent measures to strengthen the INHS by launching an investment plan to increase hospital capacity.

Specifically, the Decree Law of 9 March 2020 n. 14 (henceforth “decree”) [27] introduced Urgent provisions for the strengthening of the National Health Service in relation to the COVID-19 emergency.

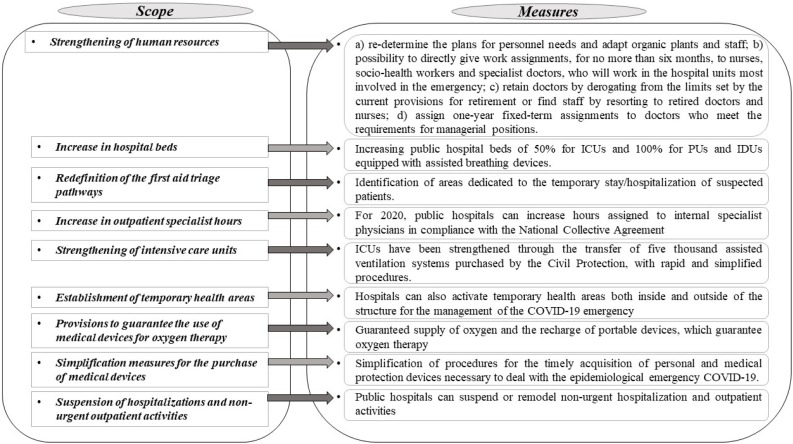

Fig. 1 synthetizes the introduced measures.

Fig. 1.

Decree’s main measures.

The reforms approved during the first months of the emergency mainly aimed to strengthen hospitals to face the acute phases of the illness. Some regions expanded the number of beds in hospital operating units; other regions (such as Lombardy and Marche) decided to build new hospital facilities exclusively dedicated to the care of COVID 19 patients, which had very high construction costs for structures that were never used during the first wave due to the decrease in infected subjects.

"Taking charge" of patients for the effective and efficient management of the health demand due to COVID-19 was placed at the centre of attention only during the second phase.

With the approval of subsequent regulatory interventions (the law decree nr. 34 of 19 May 2020 [28]), the Italian government introduced urgent territorial assistance provisions with the objective to monitor and implement surveillance of the circulation of SARS-CoV-2, confirmed cases and their contacts to promptly intercept any outbreaks of transmission of the virus in addition to ensuring the early management of infected patients. Thus, attention shifted to the surveillance and prevention of the virus circulation to improve health outcomes and avoid or reduce hospitalizations.

Policies adopted in some regions affect future national developments. In particular, the territorial management approach adopted in Veneto characterized by a lower hospitalization rate and a higher incidence of testing, and the combined hospital-territorial management model adopted in Emilia-Romagna and Piedmont characterized by an intermediate level of hospitalization and an intermediate level of testing could deeply affect future choices regarding INHS.

3.1. Preliminary outcomes

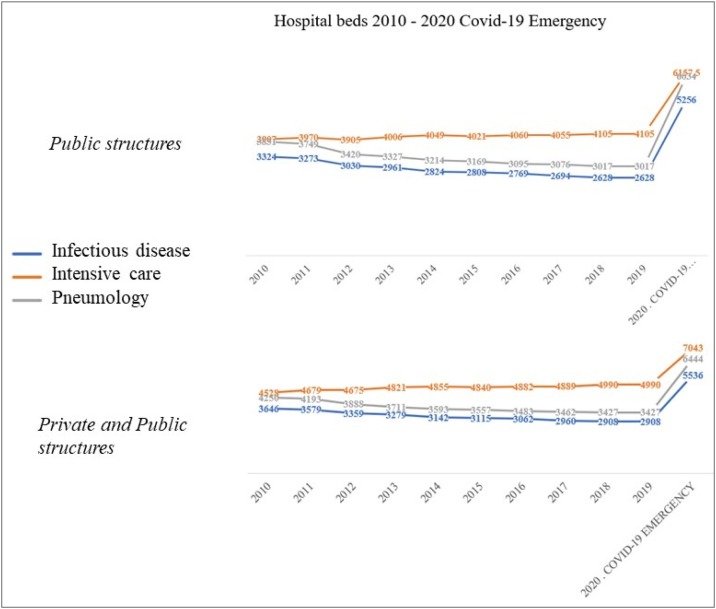

The COVID-19 emergency forced the introduction of new measures aiming to increase resources to expand the INHS capacity. It is possible to analyse the impact of these measures in terms of public hospital beds in ICUs, PUs and IDUs.

As shown in Fig. 2 , the number of beds in public hospitals decreased overall from a total of 11,062 in 2010 to a total of 9750 in 2019. In 2020, the expected increase in the number of beds could be approximately 17,448 (+ 100 % in IDUs and PUs; +50 % in ICUs [29]).

Fig. 2.

Trends in the number of beds in healthcare structures (IDUs, PUs, and ICUs).

By considering support from accredited private structures, the total expected increase is over 19,000 hospital beds with an overall increase in the health system capacity of 68 % from a total of 11,325 beds in 2019 in both public and accredited private hospitals to a total of 19,023 in 2020 (of which 1550 will be contributed by accredited private hospitals).

Moreover, in response to the COVID-19 emergency, the new decree highlighted the need to increase the healthcare staff available in public health organizations. Therefore, the decree provided for the allocation of approximately 660 million Euro distributed among Italian regions for hiring new health personnel [27]. The expected increase is approximately 20,000 units allocated among doctors (5000), nurses (10,000) and health workers (5000) [30].

3.2. Covid-19 containment measures and the Italian health system: future steps

The emergency could significantly affect future health policy choices worldwide. In Italy, the COVID-19 emergency imposed the adoption of extraordinary measures, which seem to have repealed 30 years of Italian reforms with a single stroke. The end of the emergency could reopen the debate regarding the government and the organization of the health system, whose management approach over the past 30 years was inspired by managerialism. The emergency highlighted the following:

-

•

The re-centralization tendencies in regionalized health systems [31]. Until last June (2020), the debate was still ongoing; researchers and policy makers discussed the complexity of the regionalization of health care in Italy and the increasing role of the central government, which gradually eroded the autonomy of the regions and promoted the new re-centralization of the health system to reduce regional differences in delivery and guarantee equity.

-

•

A new enhancement of hospital offerings following the intense de-hospitalization process that began in the 1990s and an increase in health care workers characterized by 40 years of containment policies.

-

•

The absence of integration and coordination to manage competition among health providers, i.e., private/public and public/public (by means of an incentive system). When health care providers compete, coordination and information are left to market forces via patients’ ability to choose the best provider, which raises concerns during a pandemic, when swift decision-making reaching all health providers is crucial [32]. An integrated management of public and private offerings could manage the supply of hospital beds and coordination with other social services (e.g., transfers in and out of nursing homes).

4. Concluding remarks

To address the COVID-19 pandemic, strict social containment measures have been adopted worldwide. Health care systems have been reorganized to cope with the enormous increase in the numbers of acutely ill patients. From the beginning of the epidemic to 7 November 2020, the surveillance system of the Italian Institute of Health reported 844,579 COVID-19 cases and 40,212 deaths [33]. The lockdown measures made it possible to control the SARS-CoV-2 virus epidemic in the national territory, highlighting the criticalities of the response by the Italian government. The adopted measures mainly focused on hospital settings; in addition to worsened health outcomes, the measures generated enormous overall costs for hospital admissions and a reduction in ordinary hospitalizations, which could result in the poor health of patients in the future and therefore greater forthcoming health expenditures. Therefore, the total impact on hospital expenditure reaches € 1,586,858,655, of which 35 % represents the expenditure incurred in the Lombardy Region alone (the epicentre of the epidemic) [34].

Furthermore, the increase in cases starting from September 2020 and the difficulties in implementing effective tracking and prevention systems have placed the availability of health infrastructure at the centre of attention to cope with the potential risks of new exponential growth.

Generally, the pandemic highlighted the unpreparedness of all health systems to face the situation; the reforms adopted over the last 30 years reduced the public health system capacity. The first wave of the pandemic seemed to indicate that the health system capacity in various countries is a variable determined to guarantee an effective response of the health system in avoiding deaths. The necessity to strengthen the primary care sector to implement preventive health initiatives, in addition to the surveillance system emerged only during the second phase.

Declaration of Competing Interest

None.

Acknowledgements

The authors thank the Department of Clinical and Experimental Medicine -Magna Graecia University - for the support for the language revision of the paper.

References

- 1.Carinci F. Covid-19: preparedness, decentralisation, and the hunt for patient zero. BMJ. 2020;368 doi: 10.1136/bmj.m799. bmj.m799. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Pisano G.P., Sadun R., Zanini M. 2020. Lessons from Italy’s response to coronavirus. Harvard business review.https://hbr.org/ [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ferrè F., Cuccurullo C., Lega F. The challenge and the future of health care turnaround plans: evidence from the Italian experience. Health Policy. 2012;106:3–9. doi: 10.1016/j.healthpol.2012.03.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Cavalieri M., Ferrante L. Does fiscal decentralization improve health outcomes? Evidence from infant mortality in Italy. Social Science & Medicine. 2016;164:74–88. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2016.07.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hood C. A public management for all seasons? Public administration. 1991;69:3–19. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Fattore G. Health care and cost containment in the European Union. Routledge; 2019. Cost containment and reforms in the Italian National health service; pp. 513–546. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Pavolini E., Kuhlmann E., Agartan T.I., Burau V., Mannion R., Speed E. Healthcare governance, professions and populism: is there a relationship? An explorative comparison of five European countries. Health Policy. 2018;122:1140–1148. doi: 10.1016/j.healthpol.2018.08.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Anessi‐Pessina E., Cantù E. Whither managerialism in the Italian national health service? The International Journal of Health Planning and Management. 2006;21:327–355. doi: 10.1002/hpm.861. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Greer S.L., da Fonseca E.M. In: The palgrave International handbook of healthcare policy and governance. Kuhlmann E., Blank R.H., Bourgeault I.L., Wendt C., editors. Palgrave Macmillan UK; London: 2015. Decentralization and health system governance; pp. 409–424. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Saltman R.B.B., Bankauskaite V., Vrangbaek K., editors. Decentralization in health care: strategies and outcomes. Open University Press; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Bordignon M., Turati G. Bailing out expectations and public health expenditure. J Health Economic. 2009;28:305–321. doi: 10.1016/j.jhealeco.2008.12.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Fetter R.B., Thompson J.D., Mills R.E. A system for cost and reimbursement control in hospitals. The Yale Journal of Biologiy and Medicine. 1976;49:123–136. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Fetter R.B., Mills R.E., Riedel D.C., et al. The application of diagnostic specific cost profiles to cost and reimbursement control in hospitals. Journal of Medical Systems. 1977;1:137–149. doi: 10.1007/BF02285281. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.OECD . OECD Publishing; 2014. OECD reviews of health care quality: italy 2014; raising standards. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Clemens J., Gottlieb J.D., Hicks J. 2020. How would medicare for all affect health system capacity? Evidence from medicare for some. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Fisher E.S., Wennberg J.E., Stukel T.A., Skinner J.S., Sharp S.M., Freeman J.L., et al. Associations among hospital capacity, utilization, and mortality of US Medicare beneficiaries, controlling for sociodemographic factors. Health Services Research. 2000;34(6):1351. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Emanuel E.J., Persad G., Upshur R., Thome B., Parker M., Glickman A., et al. Fair allocation of scarce medical resources in the time of Covid-19. The New England Journal of Medicine. 2020;382:2049–2055. doi: 10.1056/NEJMsb2005114. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Fisher E.S., Wennberg D.E., Stukel T.A., Gottlieb D.J., Lucas F.L., Pinder E.L. The Implications of Regional Variations in Medicare Spending. Part 2: Health Outcomes and Satisfaction with Care. Annals of Internal Medicine. 2003;138(4):288–298. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-138-4-200302180-00007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Fattore G., Torbica A. Inpatient reimbursement system in Italy: How do tariffs relate to costs? Health Care Manage Science. 2006;9:251–258. doi: 10.1007/s10729-006-9092-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.2016. Patto per la salute 2014.www.salute.gov.it/portale/pattosalute/dettaglioContenutiPattoSalute.jsp?lingua=italiano&id=1299&area=pattoSalute&menu=vuoto [Google Scholar]

- 21.Bobbini M., Cinelli G., Gugiatti A., Petracca F. Rapporto oasi. 2019. La struttura e le attività del SSN; pp. 33–98. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Legge 23 dicembre . 2009. 2009, n. 191, “Disposizioni per la formazione del bilancio annuale e pluriennale dello Stato - Legge finanziaria 2010.https://www.gazzettaufficiale.it/ [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kringos D.S., Boerma W.G., Hutchinson A., Saltman R.B., editors. Building primary care in a changing Europe. Case studies. WHO; United Kingdom: 2015. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Mauro M., Maresso A., Guglielmo A. Health decentralization at a dead-end: towards new recovery plans for Italian hospitals. Health Policy. 2017;121:582–587. doi: 10.1016/j.healthpol.2017.04.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Anelli S., Baratta C., Barberini E., Gargiulo G., Lucarini S., Pecoraro F., et al. Emergenza COVID-19: studio del sistema dei ricoveri e delle risposte nei modelli organizzativi nelle diverse regioni italiane. SMART eLAB. 2020;15(June):1–16. doi: 10.30441/smart-elab.v15i.170. 2020. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Mugnai G., Bilato C. Letter to the editor: Covid-19 in Italy: lesson from the veneto region. European Journal of Internal Medicine. 2020;77:161–162. doi: 10.1016/j.ejim.2020.05.039. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Decreto-Legge 9 Marzo . 2020. 2020, n. 14. “Disposizioni urgenti per il potenziamento del Servizio sanitario nazionale in relazione all’emergenza COVID-19”.https://www.gazzettaufficiale.it/ [Google Scholar]

- 28.2020. Decreto legge nr. 34 of 19 May 2020. Misure urgenti in materia di salute, sostegno al lavoro e all’economia, nonche’ di politiche sociali connesse all’emergenza epidemiologica da COVID-19. (20G00052) (GU Serie Generale n.128 del 19-05. Suppl. Ordinario n. 21. [Google Scholar]

- 29.2020. Circolare del Ministero della Salute. 1° marzo 2020. “Incremento disponibilità posti letto del Servizio Sanitario Nazionale e ulteriori indicazioni relative alla gestione dell’emergenza.www.salute.gov.it/ [Google Scholar]

- 30.2020. Sanità24. “Coronavirus/ in Gazzetta il decreto che arruola 20mila tra medici, operatori e Oss. Ai contratti-spot vanno 660 milioni”.https://www.sanita24.ilsole24ore.com/ [Google Scholar]

- 31.Pisano G.P., Sadun R., Zanini M. Lessons from Italy’s response to coronavirus. Harvard Business Review website. 2020;27(March) [Google Scholar]

- 32.Font J.C., Levaggi R., Turati G. 2020. Hospital network management amidst COVID-19: lessons from the Italian regions, LSE Business Review, 2020.https://blogs.lse.ac.uk/businessreview/2020/09/17/hospital-network-management-amidst-covid-19-lessons-from-the-italian-regions/ [Google Scholar]

- 33.2020. Istituto Superiore Di Sanità. Epidemia COVID-19, aggiornamento nazionale: 7 novembre.https://www.epicentro.iss.it/coronavirus/bollettino/Bollettino-sorveglianza-integrata-COVID-19_7-novembre-2020.pdf Available online at: [Google Scholar]

- 34.ALTEMS . 2020. Analisi Dei Modelli Organizzativi Di Risposta al Covid-19.https://altems.unicatt.it/altems-covid-19 Available online at: [Google Scholar]