Abstract

During the surge of Coronavirus Disease 2019 (COVID-19) infections in March and April 2020, many skilled-nursing facilities in the Boston area closed to COVID-19 post-acute admissions because of infection control concerns and staffing shortages. Local government and health care leaders collaborated to establish a 1000-bed field hospital for patients with COVID-19, with 500 respite beds for the undomiciled and 500 post-acute care (PAC) beds within 9 days. The PAC hospital provided care for 394 patients over 7 weeks, from April 10 to June 2, 2020. In this report, we describe our implementation strategy, including organization structure, admissions criteria, and clinical services. Partnership with government, military, and local health care organizations was essential for logistical and medical support. In addition, dynamic workflows necessitated clear communication pathways, clinical operations expertise, and highly adaptable staff.

Keywords: Coronavirus (COVID-19), Boston Hope, field hospital, post-acute care, alternative care site (ACS)

Problem

Skilled-nursing facilities (SNFs) across the nation and world have been devastated by the COVID-19 pandemic.1 , 2 In Massachusetts, 64% of COVID-19 deaths have been patients in long-term care facilities.3 During the surge of COVID-19 cases in March and April 2020, many Boston-area SNFs were unable to admit post-acute care (PAC) patients with COVID-19 infection due to limited testing and personal protective equipment, internal COVID-19 outbreaks, and staffing shortages.

Many SNFs would eventually close to admissions. With hospitals reaching surge capacity and rising COVID-19 infections, the need to decompress acute care hospitals by increasing access to PAC for patients recovering from COVID-19 infection was immediate.4

Innovation

To address this critical shortage, local government and health care leaders collaborated to rapidly establish a 1000-bed field hospital. A local health care organization for the homeless would manage 500 respite beds for individuals with COVID-19 who only required isolation. A large nonprofit multicenter health care system (MHS) including 2 academic medical centers (AMCs), a PAC network, and several community hospitals would provide financial, operational, and human resources to develop and manage 500 PAC beds for patients with COVID-19 requiring transitional or respite care from hospitals and outpatient settings.

Implementation

Site Assembly

The field hospital was commissioned as part of the Commonwealth of Massachusetts COVID-19 response. Led by the MHS, the planning team drew heavily on local resources, including other AMCs, nonprofit organizations, and veterans’ organizations to envision and scale the 500-bed PAC facility within the local convention center.

In 9 days of near continuous construction, convention center staff worked with the field hospital leadership team and a local construction company to convert the center into a hospital, meeting infection prevention and clinical care standards (Figure 1 ). Biomedical and durable equipment lists were generated using Federal Emergency Management Agency guidelines5 and input from local experts; and were sourced commercially and from local hospitals, nonprofits, and private sector donations. With state support, the National Guard assisted with on-site security, logistics, and set-up.

Fig. 1.

Photograph of the field hospital in the final stages of construction. A downloadable PDF of this form is available at www.sciencedirect.com.

Boston Hope

Organization

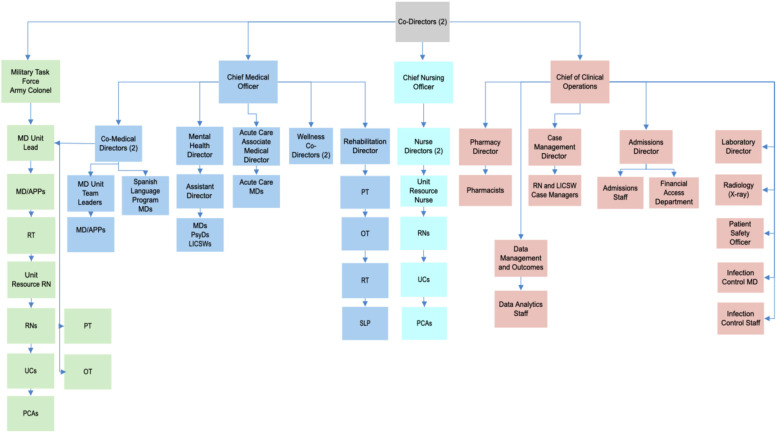

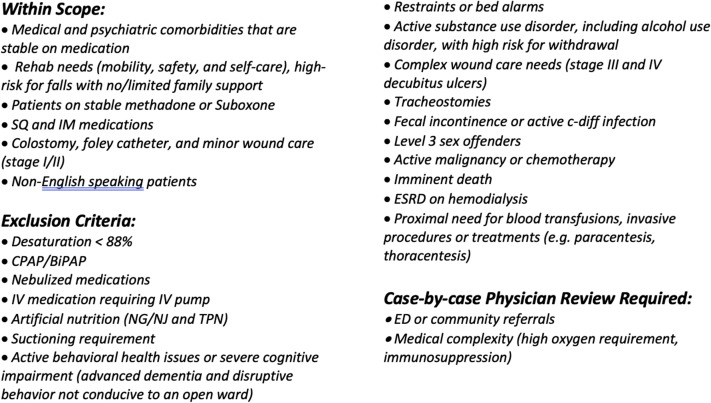

The Incident Command System was used and was led by a military general Incident Commander, supported by 3 others (1 military Deputy Commander, 2 clinical Co-Directors), and organized into clinical care and operations, human resources, facilities/logistics, finance, data management, and information technology. The clinical care and operations leadership structure was modified based on dynamic needs (Figure 2 ) and included clinical teams and ancillary services (Table 1 ). Patient referrals were accepted from throughout the region and were screened using rigorous admissions criteria (Figure 3).

Fig. 2.

Clinical care and operations organization chart. APP, advanced practice practitioner; LICSW, licensed independent clinical social worker; MD, physician; OT, occupational therapist; PCA, patient care attendant; PT, physical therapist; PsyD, psychologist; RN, registered nurse; RT, respiratory therapy; SLP, speech-language pathologist; UC, unit coordinator. A downloadable PDF of this form is available at www.sciencedirect.com.

Table 1.

Clinical, Operations, and Ancillary Services

| Clinical Teams | Description |

|---|---|

| Clinical Leadership (Figure 2) |

|

| MD/APP Staffing and Workflow |

|

| Nurse Staffing and Workflow |

|

| Acute Care and Code Team |

|

| Admissions Staff and Workflow |

|

| Mental Health |

|

| PT/OT/SLP |

|

| Respiratory Therapy |

|

| Case Management |

|

| Operations and Ancillary Services | Description |

|---|---|

| Interdisciplinary Huddles |

|

| Electronic Health Record |

|

| Pharmacy Services |

|

| Laboratory Services |

|

| Infection Control |

|

| Spanish Language Program |

|

| Radiology |

|

| Wellness |

|

| Sub-specialty Virtual Consultations |

|

ACLS, advanced cardiac life support; APP, advanced practice practitioner; BSN, Bachelor of Science in Nursing; CMO, Chief Medical Officer; CNO, Chief Nursing Officer; EHR, electronic health record; FTE, full-time equivalent; LICSW, licensed independent clinical social worker; MD, physician; MHS, Multicenter Healthcare System. OT, occupational therapist; PAC, post-acute care; PPE, personal protective equipment; PT, physical therapist; RN, registered nurse; RT, respiratory therapy; SLP, speech-language pathologist.

Fig. 3.

Admission inclusion and exclusion criteria. BiPAP, bilevel positive airway pressure; c-diff, Clostridium difficile; CPAP, continuous positive airway pressure; ED, emergency department; ESRD, end-stage renal disease; IM, intramuscular; IV, intravenous; NG, nasogastric; NJ, nasojejunal; SQ, subcutaneous; TPN, total parenteral nutrition. A downloadable PDF of this form is available at www.sciencedirect.com.

Clinical and administrative staffing were provided by local health care organizations and an Army Reserves Military Task Force. The hospital was licensed as a long-term acute care hospital under the MHS. Emergency credentialing and privilege processes facilitated rapid onboarding of 124 physicians and advanced practice practitioners. Of note, 66% were generalists (eg, family medicine or internal medicine), and 34% were from other fields (eg, orthopedics, anesthesia, dermatology, and pediatrics). Clinical staffing necessitated recruitment from local organizations as the AMCs re-deployed most staff for COVID-19 care. In all, more than 1000 staff were onboarded.

Results

A total of 394 patients were admitted over 7 weeks from April 10 to June 2, 2020. Admissions peaked on April 17 with 25 admissions, and the last admission was on May 26. Most patients (69%) were referred from local AMCs, with 42% from safety-net hospitals with large immigrant and underinsured populations. Admissions were later opened to emergency departments (EDs) and outpatient settings. The average length of stay was 8.3 days; 71% of patients were male, the average age was 57 years, and 31% were 65 and older. Patients on average were taking 6 daily medications and had 5 active medical problems on admission. The mental health team consulted on 25% of patients.

There were no intubations, cardiopulmonary arrests, or patient deaths. There were 26 unplanned patient transfers to EDs, resulting in a readmission rate of 6.6%. Most transfers were for non-COVID issues such as chest pain, hypertension or altered mental status. Seven of these transfers returned to the field hospital from the ED or after additional hospitalization.

Nearly all (91%) patients were discharged home or to a shelter, and 15% of patients required home services such as nursing or physical/occupational therapy. Eleven patients were discharged to another PAC facility for additional rehabilitation or long-term care. Seven patients were discharged Against Medical Advice.

Race demographics were available for 69% of patients: 25% Other, 18% Black, 19% White, 4% Hispanic/Latino, and 3% Asian. Nearly half (48%) of patients reported non-English languages as their primary language, including Spanish, Haitian Creole, and Portuguese Creole.

Comment

There is limited literature to guide organizations and governments who need to scale emergent PAC facilities for patients with COVID-19.5 Our experience demonstrated it is possible to rapidly assemble and manage a COVID-19 PAC facility. This report provides a guide for others confronting similar challenges.

Partnership with local government, military, and major health care organizations was essential for logistical and medical resource support. The government and military provided infrastructure and material support for construction and supplies, physical space, and security. The MHS and other local organizations provided administrative and clinical staffing, electronic health record, laboratory, and medical supplies. The emergent nature of the pandemic required strong collaboration that may not have been possible previously due to competition for patients, market share, and other resource constraints.

Positive clinical outcomes (low hospital readmission rate, zero mortality) were likely due to rigorous admissions screening processes, generous multidisciplinary staffing (including 24 hours per day availability of acute care physicians); and an incident command structure to provide clarity regarding communication, supply chain, and leadership of human resources.

One implementation challenge was the logistical complexity of providing in-patient care in a convention center. This was addressed by identifying the appropriate patient population, specifically patients with PAC needs and not acute or hospital level of care requirements. Off-site laboratory and pharmacy for most medications was appropriate for providing PAC but would have been challenging for acute care. Cubical room layouts and bathroom distance also created challenges to providing care. To address these concerns, bathrooms with handicapped accessibility were constructed closer to patients, and patients with long-term care needs such as advanced dementia were excluded from the admissions criteria.

The rapid time frame for implementation was another challenge. This was addressed by ensuring that clinical leadership had both PAC and acute care experience as well as expertise in operations and scaling. In addition, expertise in COVID-19 disease was necessary given ever-changing care guidelines. This was facilitated by having access to a large AMC's Infection Control and Division of Infectious Disease leadership.

Workforce challenges, such as staff with varied clinical backgrounds and experience, were optimized by using team-based care and supervision to balance clinical skills and experience. One unintended but useful outcome was that patients often had access to in-person sub-specialty care (eg, orthopedics and dermatology). Finally, electronic health care record challenges were addressed by providing concise guides, access to telephone support, and generous staffing ratios to allow for on-the-job training.

The COVID-19 pandemic has exacerbated existing racial inequalities, with higher infection rates and more severe illness among communities of color and immigrants.6 Our patient population reflected these demographics, with a younger, predominantly male and non–English-speaking population who often lived in densely shared housing, in contrast with most PAC populations who tend to be older adults and frail.7 We suspect admissions were limited by patient perception that the field hospital was more of a shelter rather than a PAC hospital and other concerns around general comfort, privacy, and the no-visitor policy.

We recommend careful consideration of vulnerable populations and maximum effort to ensure equity and culturally competent care. In addition, mental health should also be prioritized as we noted that the mental and physical burden of recovery and quarantine was significant. Level of care provided should be adapted based on the facility and staff capability as well as local health care system needs.8

Our findings are limited in that we describe a single site that cared for fewer patients than expected, given the local epidemic improvement. In addition, this report lacks utilization data to determine precise clinical needs. Data analysis of patient and staff experience is in process. However, we feel this initial report provides important guidance for future COVID-19 PAC field hospitals.

The COVID-19 pandemic continues to threaten our most vulnerable members of society, including patients with PAC needs. This report describes the process that we developed for rapidly assembling a PAC facility for patients with COVID-19 and provides a road map for others facing similar challenges.

Acknowledgments

We thank Richard J. Ehrlichman, MD, Gregory Fricchione, MD, Breanne Muchemore, LICSW, CCM (SRN), Erasmo “Ray” Mitrano, MS, BS Pharm, Sean Hannigan, PT, Robyn Souza, MPH, RN, Rebecca Hill, MD, Jennifer Millen, MD, Gerald Liu, MD, Darshan Mehta, MD, Laurie Tarnell, MD, Sabrina Selim, MD, Leann Canty, MD, Dawn Osborn, MD, Heidi Dotson, CEP, Louisa Sylvia, PhD for their clinical expertise and leadership. We thank Christina Della Croce, MBA, OT/L and Bingyu Xu for clinical staffing support. We thank Elena Olson, JD, and Joseph Betancourt, MD and the Spanish Language Program. We thank Patrick Curley, Rachael Hinkley, and Natalia Harty for data acquisition. We thank the Urban Augmentation Medical Task Force 801-1 and Melinda Henderson, MD, for clinical support.

For their vision and support, we thank Charlie Baker, Massachusetts Governor; Marty Walsh, Boston Mayor; Anne Klibanski, MD, Mass General Brigham President and CEO; Gregg Meyer, MD, Senior Vice President and Chief Clinical Officer, Mass General Brigham; Brigadier General Jack Hammond, Boston Hope Incident Commander; and Michael Allard, Boston Hope Deputy Commander.

The pragmatic innovation described in this article may need to be modified for use by others; in addition, strong evidence does not yet exist regarding efficacy or effectiveness. Therefore, successful implementation and outcomes cannot be assured. When necessary, administrative and legal review conducted with due diligence may be appropriate before implementing a pragmatic innovation.

Footnotes

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Mass General Brigham, the City of Boston, the Commonwealth of Massachusetts, United States Northern Command, and the Massachusetts Convention Center Authority provided funding and/or services to support Boston Hope. At the time of submission, financial support had also been requested from the Federal Emergency Management Agency.

References

- 1.Grabowski D.C., Mor V. Nursing home care in crisis in the wake of COVID-19. JAMA. 2020;324:23–24. doi: 10.1001/jama.2020.8524. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Comas-Herrera A., Zalakain J., Litwin C. Mortality associated with COVID-19 outbreaks in care homes: Early international evidence. LTCcovid.org, International Long-Term Care Policy Network, CPEC-LSE. https://ltccovid.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/06/Mortality-associated-with-COVID-among-people-who-use-long-term-care-26-June-1.pdf Available at:

- 3.Massachusetts Department of Public Health COVID-19 Dashboard - Dashboard of Public Health Indicators. Commonwealth of Massachusetts Department of Public Health. https://www.mass.gov/doc/covid-19-dashboard-august-19-2020/download Available at:

- 4.Grabowski D.C., Joynt Maddox K.E. Postacute care preparedness for COVID-19: Thinking ahead. JAMA. 2020;323:2007–2008. doi: 10.1001/jama.2020.4686. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Medical Shelter Staff Supples, and Equipment for the states of New York and New Jersey. Department of Homeland Security (DHS) Federal Emergency Management Agency (FEMA) https://beta.sam.gov/opp/3e390a69085e436086ba00edded570a6/view Available at:

- 6.Anyane-Yeboa A., Sato T., Sakuraba A. Racial disparities in COVID-19 deaths reveal harsh truths about structural inequality in America. J Intern Med. 2020;288:479–480. doi: 10.1111/joim.13117. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kojima G. Prevalence of frailty in nursing homes: A systematic review and meta-analysis. J Am Med Dir Assoc. 2015;16:940–945. doi: 10.1016/j.jamda.2015.06.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Meyer G.S., Blanchfield B.B., Bohmer R.M. 2020 May 22. Alternative care sites for the Covid-19 pandemic: The early U.S. and U.K. experience. NEJM Catalyst. [Epub ahead of print] [Google Scholar]