Abstract

Background

Lung ultrasound (LUS) has shown to correlate well with the findings obtained by chest computed tomography (CT) in acute-phase COVID-19. Although there is a significant correlation between blood biomarkers and CT radiological findings, a potential correlation between biochemical parameters and LUS images is still unknown. Our purpose was to evaluate whether mortality can be predicted from either of two lung ultrasound scoring systems (LUSS) as well as the potential association between lung lesions visualised by LUS and blood biomarkers.

Methods

We performed a retrospective observational study on 45 patients aged > 70 years with SARS-CoV-2 infection who required hospitalisation. LUS was carried out at admission and on day 7, when the clinical course was favourable or earlier in case of worsening. Disease severity was scored by means of LUSS in 8 (LUSS8) and in 12 (LUSS12) quadrants. LUS and blood draw for inflammatory marker analysis were performed at the same time.

Results

LUSS8 vs LUSS12 predicted mortality in 93.3% vs 91.1% of the cases; their associated odds ratios (OR) were 1.67 (95% CI 1.20–2.31) and 1.57 (95% CI 1.10–2.23), respectively. The association between biochemical parameters and LUSS scores was significant for ferritin; the OR for LUSS12 was 1.005 (95% CI 1.001–1.009) and for LUSS8 1.005 (95% CI 1.0–1.1), using thresholds for both of them.

Conclusions

The prognostic capacity of LUSS12 does not surpass that of LUSS8. There is a correlation between ferritin levels and LUSS.

Keywords: COVID-19, Ultrasound, Biomarkers, Ferritin, Prognosis

1. Introduction

The World Health Organization (WHO) has declared COVID-19 a pandemic [1]. Although current evidence suggests that most infections manifest mildly, up to 16% of cases may require hospital admission for developing severe pneumonia with acute respiratory distress syndrome (ARDS), sepsis, and even septic shock [2]. A large study carried out in Spain with more than 12 000 patients showed a mortality rate of less than 2% in patients under 40 years of age, but values from 25% to 50% in individuals over the age of 70 years, which highlights the vulnerability of the elderly [3].

Due to its high sensitivity, lung ultrasound (LUS) is considered a suitable alternative to conventional radiological methods to diagnose pneumonia. Various scientific societies have highlighted its utility in acute-phase COVID-19, as the resulting data showed a good correlation with those from high-resolution computed tomography (HRCT) of the chest. Based on these findings, the technique has gained importance both for disease diagnosis as well as follow-up, as it can facilitate daily monitoring with no need for radiation or intra-hospital patient transfer [4], [5], [6], [7], [8].

Given the unpredictable evolution of the disease, multiple research has evaluated indicators that may correlate with a more unfavourable course. Radiological patterns and their extent in COVID-19 have been described as being of prognostic value [9], [10]. In addition, different serum biomarkers, such as leukocyte and lymphocyte counts, lactate dehydrogenase (LDH) levels, D-dimer, procalcitonin, troponin I, and ferritin seem to provide information on the severity of the process [11], [12], [13], [14], [15], [16]. Although scientific evidence correlates serum biomarkers with chest computed tomography (CT) findings [17], there are no studies yet to evaluate any correlation between biochemical parameters and LUS imaging.

The aim of our study was to evaluate the mortality prediction capacity of two lung ultrasound scoring systems (LUSS), on the one hand, and the potential correlations of the extension and severity of LUS-visualised, SARS-Cov-2 induced lung lesions and serum biomarkers in patients over 70 years of age, on the other hand.

2. Methods

2.1. Study design and participants

This was an observational study with retrospective follow-up of patients older than 70 years with SARS-CoV-2 infection, consecutively admitted to a secondary hospital in the island of Tenerife (Spain) in the period of 1 February 2020 to 15 May 2020. Diagnosis was made in all patients by means of real-time reverse-transcription PCR of SARS-CoV-2 RNA from nasopharyngeal smears. The only exclusion criteria was when LUS did not coincide with blood draw on the same day.

2.2. Variables

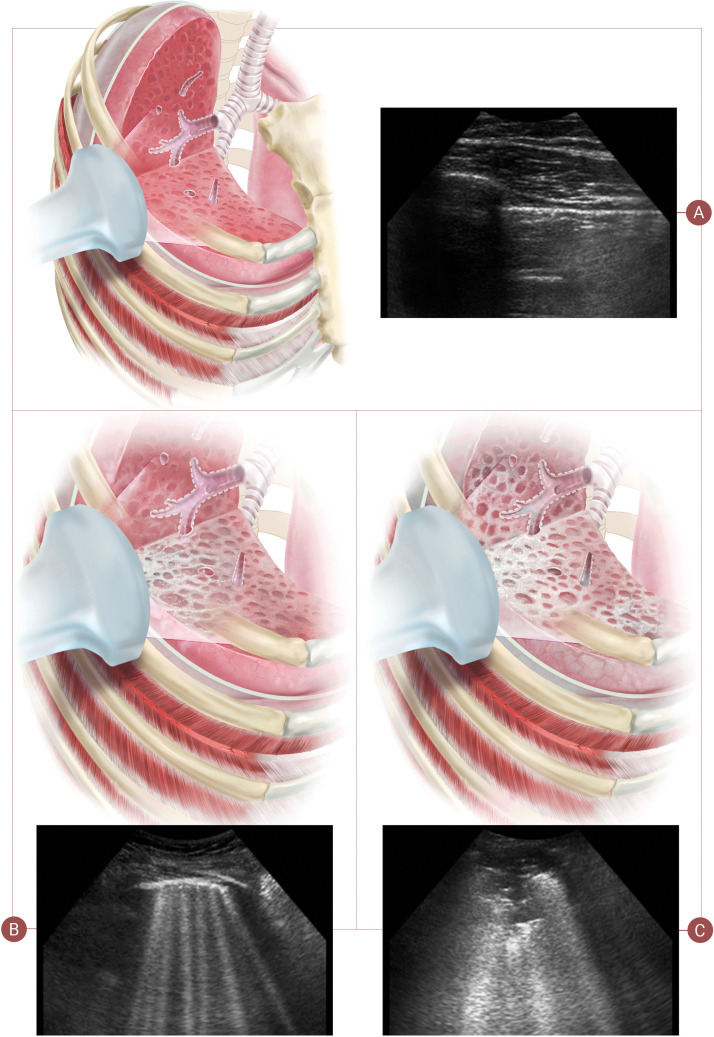

Patient demographic and comorbidity data were collected at hospital admission. All patients underwent two ultrasound examinations, the first on admission and the second on day 7 in case of a favourable clinical course, but the interval was shortened in the event of clinical deterioration. Extent and severity of the ultrasound findings was determined by using two scoring protocols, LUSS with 8 quadrants (LUSS8) and LUSS with 12 quadrants (LUSS12) [18], [19]. Both protocols assign scores of 0–3, where 0 stands for pattern A, 1 for pattern B (i.e. non-confluent B-lines), 2 for confluent B-lines, and 3 for consolidation, i.e. pattern C (Fig. 1 ) [20], [21].

Fig. 1.

Patterns of lung ultrasound. Pattern A: score 0 with a fine pleural line and visible A-lines. Pattern B: score 1 characterised by non-confluent B-lines and a fragmented pleural line and score 2 with abundant, coalescing B-lines. Pattern C: score 3 is characterised by consolidations.

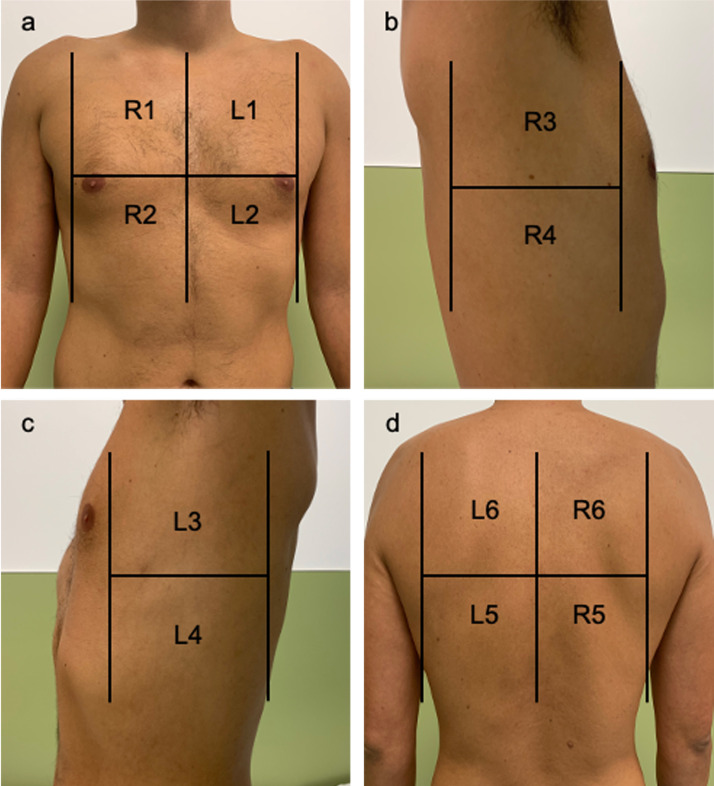

In the LUSS8 protocol, 8 locations were analysed. They consisted of four quadrants in each hemi-thorax (the anterior region of the chest with its upper anterior and lower anterior quadrant and the axillary thorax with its upper lateral and lower lateral quadrants) (Fig. 2 ). Scores ranged from 0 to 24.

Fig. 2.

Areas of lung ultrasound examination. a: the anterior region of the chest with its upper anterior and lower anterior quadrant of the right (R1–R2) and left (L1–L2) hemi-thorax; b,c: the axillary thorax with its upper lateral and lower lateral quadrants of the right (R3–R4) and left (L3–L4) hemi-thorax. d) The lower and upper quadrants of the posterior thorax of the right (R5–R6) and left (L5–L6) hemi-thorax.

In the LUSS12 protocol, 12 quadrants were analysed. The upper and lower quadrants of the posterior thorax were added to the locations mentioned above, and 6 zones were explored in each hemi-thorax (Fig. 2). Scores ranged from 0 to 36.

Ultrasound scans and scoring were performed by a single operator experienced in LUS. A Philips EnVisor C ultrasound scanner (Philips Eindhoven, The Netherlands), equipped with a 3–5 Mhz convex probe or a 5–13 Mhz linear probe, was used according to the patient's physical characteristics and the region to explore. Images and videos were recorded on a computer.

Together with ultrasound evaluation, blood samples were obtained to determine leukocyte and lymphocyte numbers, D-dimers, ferritin, procalcitonin, and C-reactive protein (CRP).

2.3. Ethics

The study was approved by the Research Ethics Committee of the University Hospital Nuestra Señora de la Candelaria.

2.4. Statistical analyses

Continuous variables were expressed as means ± SD and categories as counts and percentages. For bivariate analyses, we used Pearson's correlation to explore linear associations between continuous variables. To compare means of two independent sample groups, Student's t-test was applied. Adjusted odds ratio (OR) was obtained by multivariate logistic regression between the variable mortality and the distinct, sex-adjusted scores and comorbidities (defined by age-adjusted Charlson comorbidity index). Following Manivel et al. [22], a cut-off point of ≤15> was applied for LUSS12. For LUSS8, the cut-off point was obtained taking into account the distribution of data in relation to mortality. Adjusted OR was obtained for the dichotomised score, including the significant biomarkers in the bivariate analysis, and adjusted by sex and age-adjusted Charlson index. ORs were accompanied by their 95% CI (confidence interval). Statistical significance was set at 5% and a trend towards significance accepted for P < 0.1. Analyses were conducted with SPSS software (version 21; SPSS, Chicago, IL, USA).

3. Results

3.1. Study population

A total of 45 patients were included. Their baseline characteristics are shown in Table 1 . Women accounted for the majority (55.6%) of patients. The mean age was 82 ± 9.9 years, and the most frequent comorbidities were arterial hypertension (66.7%), dyslipidemia (62.2%) and Type 2 diabetes mellitus (42.2%). The age-adjusted Charlson index was de 6.5 ± 2.4. A total of 10 patients (22%) died during hospital stay. The mean follow-up of the survivors was 20.2 ± 4.7 days and 7.4 ± 5.4 days in the group of deceased patients.

Table 1.

Baseline characteristics of all included patients.

| Patients n | 45 |

|---|---|

| Male n (%) | 20 (44.4) |

| Age years (mean ± SD) | 82.4 ± 9.9 |

| Charlson index, age-adjusted (mean ± SD) | 6.5 ± 2.4 |

| Arterial hypertension n (%) | 30 (66.7) |

| Type 2 diabetes mellitus n (%) | 19 (42.2) |

| Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease n (%) | 12 (26.7) |

| Dyslipidemia n (%) | 28 (62.2) |

| Chronic kidney disease n (%) | 11 (24.4) |

| Moderate-severe cognitive decline n (%) | 7 (15.9) |

| Hypothyroidism n (%) | 6 (13.3) |

| Chronic atrial fibrillation n (%) | 2 (4.4) |

| Neoplasms (solid tumour, leukaemia, lymphoma) n (%) | 2 (4.4) |

SD: standard deviation.

The deceased had a higher prevalence of hypertension, dyslipidemia, and ischaemic heart disease than the survivors (P < 0.05), as well as increased D-dimer (5344.3 ± 4284.2 μg/L vs 1389.8 ± 2663.9 μg/L; P = 0.006) and ferritin (969.7 ± 489.9 μg/L vs 324.9 ± 228.3 μg/L; P < 0.001) levels, and leukocyte counts (14.2 ± 6.4 × 109/L vs 6.2 ± 1.9 × 109/L; P = 0.03) in their control analyses. Onset of symptoms prior to admission was 1.06 ± 1.45 days in patients who were eventually discharged from hospital compared to 2.5 ± 0.97 days in patients who died. The control thoracic ultrasound examination was performed earlier in subjects who finally died (5.50 ± 2.25 days after baseline ultrasound evaluation) compared to the group that overcame the process (7.14 ± 0.36 days). The major ultrasound alterations, when applying LUSS8, were mainly located in the anterosuperior (R1 and L1) and lower axillary (R4 and L4) quadrant (both in the baseline and the control ultrasound examination). Applying LUSS12, the most frequently affected areas were detected in the anterosuperior, the lower axillary, and the posterobasal quadrant (R5 and L5) in both ultrasound assessments.

3.2. Association between mortality and LUSS scores

As compared to survivors, patients who finally died had higher scores both in LUSS8 (13 ± 3.59, P < 0.0001) as well as LUSS12 (19.3 ± 4.32, P < 0.0001). In the adjusted multivariate model, the LUSS8 score predicted mortality in 93,3% of the cases; the risk of dying increased by 67% per increased score unit (OR 1.67, 95% CI 1.20–2.31). LUSS12 predicted mortality in 91.1% of the cases (OR 1.57 95%, CI 1.10–2.23).

Furthermore, an increase in score during follow-up was associated with higher mortality in the adjusted model, OR = 1.48 (95% CI 1.06–2.07) for LUSS8 and OR = 1.57 (95% CI 1.11–2.23) for LUSS12, predicting mortality in 84.4% of the cases with either system (Table 2 ).

Table 2.

Relationship between lung ultrasound scoring system cut-off points, blood parameters and mortality.

| LUSS12 | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Blood parameter | LUSS12 ≤ 15, n = 33 |

LUSS12 > 15, n = 12 |

t-Student's | P-value |

| Mean (SD) | Mean (SD) | |||

| Leukocytes × 109/L | 6.79 (3.26) | 8.20 (3.91) | −1.22 | 0.229 |

| Lymphocytes × 109/L | 1.38 (786.58) | 1.19 (0.59) | 0.6 | 0.552 |

| D-dimer μg/L | 1157.79 (2643.68) | 1492.25 (1905.53) | −0.401 | 0.691 |

| Ferritin μg/L | 245.94 (204.24) | 700.36 (448.27) | −3.248 | 0.007 |

| CRP g/L | 3.58 (5.24) | 8.94 (8.39) | −2.073 | 0.057 |

| Procalcitonin mg/L | 1.1 (0.4) | 1.4 (1) | −1.07 | 0.305 |

| LUSS 8 | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Blood parameter | LUSS8 ≤ 10, n = 32 |

LUSS8 > 10, n = 13 |

t-Student's | P-value |

| Mean (SD) | Mean (SD) | |||

| Leukocytes × 109/L | 6.83 (3.30) | 7.99 (3.82) | 1.018 | 0.314 |

| Lymphocytes × 109/L | 1.43 (798.77) | 1.17 (0.57) | −0.634 | 0.529 |

| D-dimer μg/L | 1183.28 (2.681.86) | 1 403.77 (1852.09) | 0.27 | 0.788 |

| Ferritin μg/L | 245.13 (207.57) | 664.58 (445.02) | 3.136 | 0.008 |

| CRP g/L | 3.57 (5.32) | 8.55 (8.16) | 2.035 | 0.058 |

| Procalcitonin mg/L | 1.1 (0.4) | 1.4 (1) | 1.023 | 0.324 |

| Mortality | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Survivors, n = 35 |

Deceased, n = 10 |

t-Student's | P-value | |

| Mean (SD) | Mean (SD) | |||

| Score from LUSS12 | 6.89 (5.91) | 19.30 (4.32) | 6.171 | < 0.0001 |

| Score from LUSS8 | 4.11 (3.93) | 13.0 (3.59) | 6.416 | < 0.0001 |

| Variation LUSS12a | −0.69 (2.7) | 3.90 (3.48) | −4.43 | < 0.0001 |

| Variation LUSS8a | −0.11 (2.23) | 3.20 (3.22) | −3.05 | 0.011 |

LUSS: lung ultrasound scoring system; CRP: C-reactive protein; SD: standard deviation.

Difference between scores from the first and second ultrasound scan.

3.3. Correlation between biochemical parameters and LUSS scores

The correlation between the analysed biochemical parameters and LUSS8 and LUSS12 scores was only significant for ferritin levels and was 0.486 (P = 0.001) and 0.458 (P = 0.002), respectively. A trend towards significance was detected for CRP with a correlation of 0.269 (P = 0.074) for both scoring systems. Taking into account the cut-off scores, the difference in means of the biochemical parameters was only significant for ferritin. In patients with LUSS8 scores >10, ferritin levels were higher than in patients with scores ≤ 10, i.e. 664.6 ± 445.0 μg/L and 245.13 ± 207.6 μg/L (P = 0.008), respectively. As to LUSS12, ferritin levels were 254.9 ± 204.2 μg/L for patients with scores ≤ 15 and 700.4 ± 448.3 μg/L for those with scores > 15 (Table 2). PCR revealed a trend towards significance for either scoring systems. In the multivariate logistic regression analysis, adjusted for sex and age-adjusted Charlson comorbidity index, differences were only significant for ferritin in both system. The OR for LUSS12 was 1.005 (95% CI 1.001–1009; P = 0.023) and for LUSS8 1.005 (95% CI 1.0–1.01; P = 0.033).

4. Discussion

We draw the following two conclusions from this study: first, the ability to predict mortality from a 12-quadrant LUSS does not surpass 8-quadrant scanning. Second, there is a correlation between serum parameters (ferritin) and the degree of lesions in the lungs as identified by LUS in patients over 70 years of age with SARS-CoV-2 infection.

In acute-phase COVID-19, a good correlation between LUS and thoracic HRCT data has been reported, which emphasises the importance of LUS in both diagnosis and follow-up [7], [8]. Performing it with no need to move the patient reduces the risk of contagion, which converts the technique into a useful tool in COVID-19 disease management [4], [5], [6], [7], [8]. Most studies have focused on LUS diagnostic capacity, but only few have evaluated its prognostic value [23]. In our study, the mortality prediction capacity was similar when and independent of exploring either 8 or 12 quadrants. This data indicates that disease progression could be evaluated by solely exploring the anterior and lateral quadrants. Meiler et al. described that SARS-COV-2 infected patients with extensive lung parenchyma involvement by chest CT had a higher mortality. A bilateral extension as well as involvement of the upper and middle lobes were predictive of an unfavourable course [24]. Castelao et al. reported that involvement of the anterior thorax region detected by ultrasound imaging in patients hospitalised for COVID-19 was of prognostic value and correlated with an increased risk of requiring non-invasive ventilation support [23]. These findings are consistent with our results, as an 8-quadrant ultrasound examination encompasses the anterior and lateral thorax, areas of high prognostic impact.

This point is of special relevance in patients where, due to their clinical situation, the posterior thoracic field cannot be explored. Furthermore, the need to explore fewer quadrants reduces the exposure time of the medical staff and therefore the risk of contagion.

On the other hand, laboratory parameters, such as leukocyte and lymphocyte numbers, LDH, D-dimer, procalcitonin, troponin I, and ferritin levels are related to the clinical course of the infection and thus can provide information about a need for intensive care unit admission or the risk of mortality [11], [12], [13], [14], [15], [16]. Various studies have shown a worse course of COVID-19 in patients with higher levels of interleukin-6 and ferritin than in individuals with a milder disease course [14], [15], so that both biomarkers were suggested for patient monitoring during their hospital stay [16]. A rise in these parameters is related to a systemic inflammatory response syndrome (SIRS) [25], a so-called cytokine storm, which can progress into ARDS, darkening these patients’ prognosis. Chen et al. [13] detected higher levels of CRP, ferritin, LDH, and D-dimer in severe cases of COVID-19 compared to a milder ones. On CT scans, patients with COVID-19 generally present chest opacities, the extent of which has been correlated with laboratory parameters. A study published by Xiong et al. [17] found that elevated CRP and LDH levels correlated with the extent of pneumonia quantified by chest CT.

In our study, elevated ferritin levels correlated with high LUSS scores, which may be an expression of lung damage in the context of SIRS. Such exaggerated inflammatory response was shown to be a prognostic factor in COVID-19 patients [12]. In this sense, ultrasound findings from lung parenchyma scans are plausible to reflect disease severity and may therefore offer information on the course of the process from the very beginning.

One of the strengths of this work is that very few studies have evaluated the prognostic capacity of lung ultrasound imaging in patients with COVID-19 [23]. Moreover, as to our knowledge, this is the first study to evaluate the relationship between blood biomarkers and the extent of pleuro-pulmonary ultrasound findings in patients hospitalised for SARS-CoV-2 infection. We must put emphasis on the age range of our patients, as – although they form the most vulnerable group with a high mortality rate – only few studies have focused on this group yet [26], [27]. One of the limitations of this work is that a larger sample size could potentially have revealed correlations with other biomarkers. Furthermore, the examination was performed by a single operator, so that we cannot rule out inter-observer differences when sonographic scoring is performed by more than one person.

In conclusion, the prognostic capacity of scanning 12 fields does not seem advantageous over 8 quadrants, which allows reducing the staff exposure time and thus the risk of contagion. In addition, there is a correlation between ferritin levels and the scores obtained by LUSS in hospitalised patients older than 70 years with SARS-CoV-2 infection. Studies with a larger sample size are needed to confirm these findings.

Disclosure of interest

The authors declare that they have no competing interest.

References

- 1.Lauer S.A., Grantz K.H., Bi Q., Jones F.K., Zheng Q., Meredith H.R., et al. The incubation period of coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) from publicly reported confirmed cases: estimation and application. Ann Intern Med. 2020;172:577–582. doi: 10.7326/M20-0504. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Guan W.J., Ni Z.Y., Hu Y., Liang W.H., Ou C.Q., He J.X., et al. China medical treatment expert group for COVID-19. Clinical characteristics of coronavirus disease 2019 in China. N Engl J Med. 2020;382:1708–1720. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa2002032. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Casas Rojo JM, Antón Santos JM, Núñez-Cortés JM, Lumbreras C, Ramos Rincón JM, Roy-Vallejo E, Artero A, Arnalich Fernández F, García Bruñén JM, Vargas Nuñez JA, Freire Castro SJ, Manzano L, Perales Fraile I, Crestelo Vieitez A, Puchades F, Rodilla E, Solís Marquínez MN, Bonet Tur D, Fidalgo Moreno MP, Fonseca Aizpuru EM, Carrasco Sánchez FJ, Rabadán Pejenaute E, Rubio-Rivas M, Torres Peña JD, Gómez Huelgas R. Clinical characteristics of patients hospitalized with COVID-19 in Spain: results from the SEMI-COVID-19 Network. medRxiv preprint. doi: https://doi.org/10.1101/2020.05.24.20111971.

- 4.Pérez Pallarés J., Flandes Aldeyturriaga J., Cases Viedma E., Cordovilla Pérez R. SEPAR-AEER consensus recommendations on the usefulness of the thoracic ultrasound in the management of the patient with suspected or confirmed infection with COVID-19. Arch Bronconeumol. 2020 [S0300-2896(20)30099-5] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Wangüemert Pérez A.L. Clinical applications of pulmonary ultrasound. Aplicaciones clínicas de la ecografía pulmonar. Med Clin (Barc) 2020;154:260–268. doi: 10.1016/j.medcli.2019.11.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Chiumello D., Mongodi S., Algieri I., Vergani G.L., Orlando A., Via G., et al. Assessment of lung aeration and recruitment by CT scan and ultrasound in acute respiratory distress syndrome patients. Crit Care Med. 2018;46:1761–1768. doi: 10.1097/CCM.0000000000003340. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Peng Q.Y., Wang X.T., Zhang L.N., Chinese Critical Care Ultrasound Study Group (CCUSG) Findings of lung ultrasonography of novel corona virus pneumonia during the 2019–2020 epidemic. Intensive Care Med. 2020;46:849–850. doi: 10.1007/s00134-020-05996-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Poggiali E., Dacrema A., Bastoni D., Tinelli V., Demichele E., Mateo Ramos P., et al. Help critical care clinicians in the early diagnosis of novel coronavirus (COVID-19) pneumonia? Radiology. 2020;295:E6. doi: 10.1148/radiol.2020200847. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Li K., Wu J., Wu F., Guo D., Chen L., Fang Z., et al. Features associated with severe and critical COVID-19 pneumonia. Invest Radiol. 2020;55:327–331. doi: 10.1097/RLI.0000000000000672. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Yuan M., Yin W., Tao Z., Tan W., Hu Y. Association of radiologic findings with mortality of patients infected with 2019 novel coronavirus in Wuhan, China. PLoS One. 2020;15:e0230548. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0230548. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Wang D., Hu B., Hu C., Zhu F., Liu X., Zhang J., et al. Clinical characteristics of 138 hospitalized patients with 2019 novel coronavirus-infected pneumonia in Wuhan, China. JAMA. 2020;323:1061–1069. doi: 10.1001/jama.2020.1585. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Lippi G., Plebani M. Laboratory abnormalities in patients with COVID-2019 infection. Clin Chem Lab Med. 2020 doi: 10.1515/cclm-2020-0198. [/j/cclm.ahead-of-print/cclm-2020-0198/cclm-2020-0198.xml.doi: 10.1515/cclm-2020-0198] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Chen G., Wu D., Guo W., Cao Y., Huang D., Wang H., et al. Clinical and immunological features of severe and moderate coronavirus disease 2019. J Clin Invest. 2020;130:2620–2629. doi: 10.1172/JCI137244. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Liu T., Zhang J., Yang Y., Ma H., Li Z., Zhang J., et al. 2019. The potential role of IL-6 in monitoring severe case of coronavirus disease. [medRxiv 2020.03.01.20029769. doi: https://doi.org 10.1101/2020.03.01.20029769] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Liu T., Zhang J., Yang Y., Ma H., Li Z., Zhang J., et al. The role of interleukin-6 in monitoring severe case of coronavirus disease 2019. EMBO Mol Med. 2020:e12421. doi: 10.15252/emmm.202012421. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Henry B.M., de Oliveira M.H.S., Benoit S., Plebani M., Lippi G. Hematologic, biochemical and immune biomarker abnormalities associated with severe illness and mortality in coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19): a meta-analysis. Clin Chem Lab Med. 2020 doi: 10.1515/cclm-2020-0369. [/j/cclm.ahead-of-print/cclm-2020-0369/cclm-2020-0369.xml] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Xiong Y., Sun D., Liu Y., Fan Y., Zhao L., Li X., et al. Features of the COVID-19 infection: comparison of the initial and follow-up changes. Invest Radiol. 2020;55:332–339. doi: 10.1097/RLI.0000000000000674. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Volpicelli G., Elbarbary M., Blaivas M., Lichtenstein D.A., Mathis G., Kirkpatrick A.W., et al. International liaison committee on lung ultrasound (ILC-LUS) for international consensus conference on lung ultrasound (ICC-LUS). International evidence-based recommendations for point-of-care lung ultrasound. Intensive Care Med. 2012;38:577–591. doi: 10.1007/s00134-012-2513-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Bouhemad B., Mongodi S., Via G., Rouquette I. Ultrasound for “lung monitoring” of ventilated patients. Anesthesiology. 2015;122:437–447. doi: 10.1097/ALN.0000000000000558. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Soldati G., Smargiassi A., Inchingolo R., Buonsenso D., Perrone T., Briganti D.F., et al. Proposal for international standardization of the use of lung ultrasound for patients with COVID-19: a simple, quantitative, reproducible method. J Ultrasound Med. 2020 doi: 10.1002/jum.15285. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Tung-Chen Y., Martí de Gracia M., Díez-Tascón A., Alonso-González R., Agudo-Fernández S., Parra-Gordo M.L., et al. Correlation between chest computed tomography and lung ultrasonography in patients with coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) Ultrasound Med Biol. 2020 doi: 10.1016/j.ultrasmedbio.2020.07.003. [S0301-5629(20)30301-X] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Manivel V., Lesnewski A., Shamim S., Carbonatto G., Govindan T., CLUE: COVID-19 lung ultrasound in emergency department. Emerg Med Australas. 2020:10. doi: 10.1111/1742-6723.13546. [1111/1742-6723.13546] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Castelao J., Graziani D., Soriano J.B., Izquierdo J.L. Findings and prognostic value of lung ultrasound in COVID-19 pneumonia. J Ultrasound Med. 2020 doi: 10.1002/jum.15508. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Meiler S., Schaible J., Poschenrieder F., Scharf G., Zeman F., Rennert J., et al. performed in the early disease phase predict outcome of patients with COVID 19 pneumonia? Analysis of a cohort of 64 patients from Germany. Eur J Radiol. 2020;131:109256. doi: 10.1016/j.ejrad.2020.109256. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Meduri G.U., Headley S., Kohler G., Stentz F., Tolley E., Umberger R., et al. Persistent elevation of inflammatory cytokines predicts a poor outcome in ARDS. Plasma IL-1 beta and IL-6 levels are consistent and efficient predictors of outcome over time. Chest. 1995;107:1062–1073. doi: 10.1378/chest.107.4.1062. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Liu K., Chen Y., Lin R., Han K. Clinical features of COVID-19 in elderly patients: A comparison with young and middle-aged patients. J Infect. 2020;80:e14–e18. doi: 10.1016/j.jinf.2020.03.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Li P., Chen L., Liu Z., Pan J., Zhou D., Wang H., et al. Clinical features and short-term outcomes of elderly patients with COVID-19. Int J Infect Dis. 2020 doi: 10.1016/j.ijid.2020.05.107. [S1201-9712(20)30415-X] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]