Abstract

The COVID-19 pandemic threatens the health and well-being of older adults with multiple chronic conditions. To date, limited information exists about how Accountable Care Organizations (ACOs) are adapting to manage these patients. We surveyed 78 Medicare ACOs about their concerns for these patients during the pandemic and strategies they are employing to address them. ACOs expressed major concerns about disruptions to necessary care for this population, including the accessibility of social services and long-term care services. While certain strategies like virtual primary and specialty care visits were being used by nearly all ACOs, other services such as virtual social services, home medication delivery, and remote lab monitoring were far less commonly accessible. ACOs expressed that support for telehealth services, investment in remote monitoring capabilities, and funding for new, targeted care innovation initiatives would help them better care for vulnerable patients during this pandemic.

1. Introduction

The COVID-19 pandemic threatens the well-being of older adults and their routine health care needs, especially those with multiple chronic conditions. These high-need individuals face a double threat to their health because of the COVID-19 pandemic: higher risks for serious illness from the virus itself and disruptions in care for major chronic conditions, such as heart failure, diabetes, dementia, serious mental illness, or end-stage renal disease. Social distancing measures and fear of entering health facilities means patients are less likely to receive necessary care, with nearly half of adults reporting they or a household member postponed or skipped medical care due to the outbreak [1]. Emerging data also suggests this trend is holding for both acute conditions, with drops in emergency department visits and hospitalizations for strokes and heart attacks [2,3], as well as chronic ones, with fewer outpatient physician visits [4] and preventive services such as cancer screenings [5]. How patients fare during the pandemic may depend in large part on steps their health care providers take to help them navigate health system disruptions.

Accountable Care Organizations (ACOs), which are groups of health care clinicians and other providers that were assembled with the goal of coordinating high-quality care for Medicare beneficiaries, may be uniquely able to respond to these evolving needs. ACOs have been effective in reducing health care spending without negatively affecting quality [6], and before the pandemic, most ACOs already had programs focused on care management for people with complex needs [7]. A limited number of ACOs have also established programs to identify and address patients’ social needs, such as housing or food insecurity [8, 9, 10]. ACOs have responded to the pandemic in different ways, offering an opportunity to learn from their responses and disseminate information about effective strategies. Yet little is known about the concerns ACOs have had in caring for vulnerable patients during the pandemic and how these organizations have responded. Better understanding ACO concerns for older patients with multiple chronic conditions and strategies employed during the pandemic can inform policy and serve as a model for other health care organizations.

2. Methods

We administered a survey to ACOs about routine care concerns and strategies for older people with complex chronic conditions amid COVID-19. The survey was sent to ACOs participating in the Medicare Shared Savings Program (MSSP) as of May 2020. Using the publicly available list of ACO contacts identified by the Center for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS), we sent invitations to complete the survey by email. ACO contacts were sent two emails, one week apart, in June 2020. Informed consent was obtained from respondents for participation in this study.

Using a likert scale, we asked respondents to describe their degree of concern (no concern, some concern, and great concern) about access to eight health services during the COVID-19 pandemic (e.g. routine primary care, home medication delivery) among older patients (above age 65) with complex chronic conditions. The specific chronic conditions included heart failure, diabetes, dementia, end-stage renal disease, and serious mental illness (like schizophrenia and bipolar disorder). The survey also included questions about strategies being used to meet needs for these patients and how the ACO's use of that strategy changed from before the pandemic. Finally, we asked ACOs using an open-response format what support they would need to better care for older patients with complex chronic conditions during the pandemic.

3. Results

3.1. Characteristics of ACOs

The survey was completed by 67 respondents representing 78 ACOs of 517 ACOs (15%). A select number of respondents are leaders of multiple ACOs, such that 63 responses represented 1 ACO and 4 responses represented a total of 15 ACOs. All four regions of the United States were included among respondents (33% Northeast, 17% Midwest, 37% South, 6% West, 6% multi region), with greater representation of certain regions compared to non-respondents (17% Northeast, 22% Midwest, 46% South, 15% West). For ACOs with publicly reported data (78%), the average number of lives covered by the ACO was 21,688, compared to 20,259 among non-respondents. Among the ACOs with available information (72%), 45% were hospital-affiliated. All ACOs had a Medicare contract, of which 97.4% of ACOs participated in the Medicare Shared Savings Program and 2.6% in other Medicare ACO tracks. Not all ACOs surveyed had available financial performance data; among available data, 50% of respondent ACOs earned shared savings in 2019, compared with 38% of non-respondents. To avoid overweighting a single response, results are presented as a percentage of respondents, not weighted by ACOs.

3.2. Concerns about accessing routine care

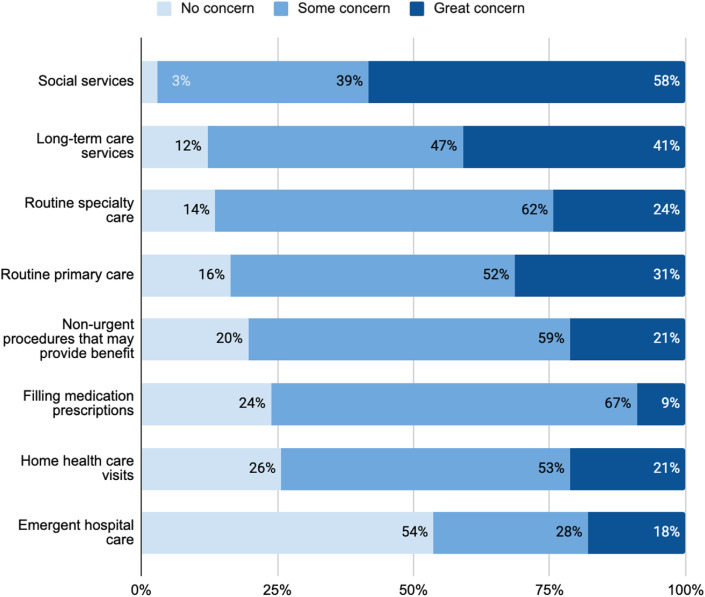

ACOs expressed widespread concerns about older patients with complex chronic conditions not being able to access needed services during the pandemic (Fig. 1 ). ACOs expressed the most worry about social services and long-term care services. Nearly all (97%) ACO respondents reported some or great concern about access to social services such as food assistance or legal services, and 88% reported some or great concern about access to long-term care services.

Fig. 1.

ACOs Are Concerned About Older Patients with Chronic Conditions Not Receiving Essential Social And Medical Care.

How concerned are you that these patients will not get the service when they need it?

ACO respondents also reported concerns for other services such as routine primary care (84%), routine specialty care (86%), and non-urgent procedures that may provide benefit (80%). The majority of ACO respondents also were concerned about patients filling medication prescriptions (76%) or receiving routine home health care services at home (74%). Over half of ACO respondents (54%) did not express concern for delay in emergent hospital care.

4. Strategies used to meet needs

4.1. Data analytics

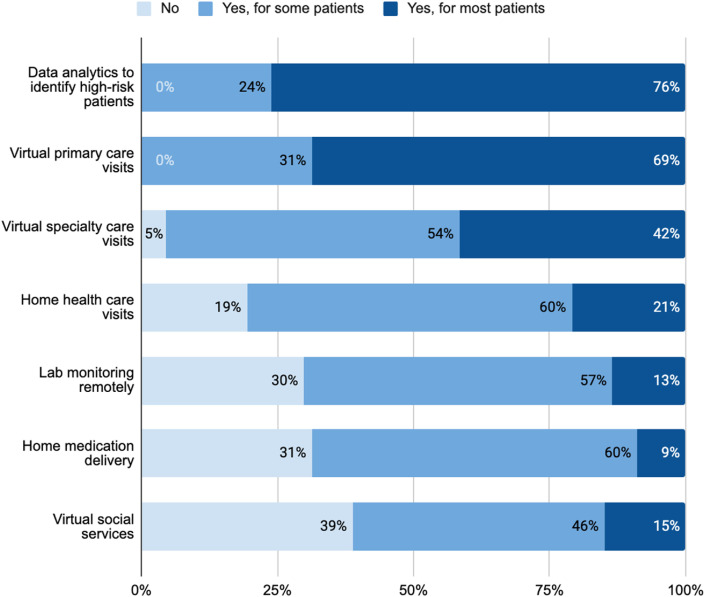

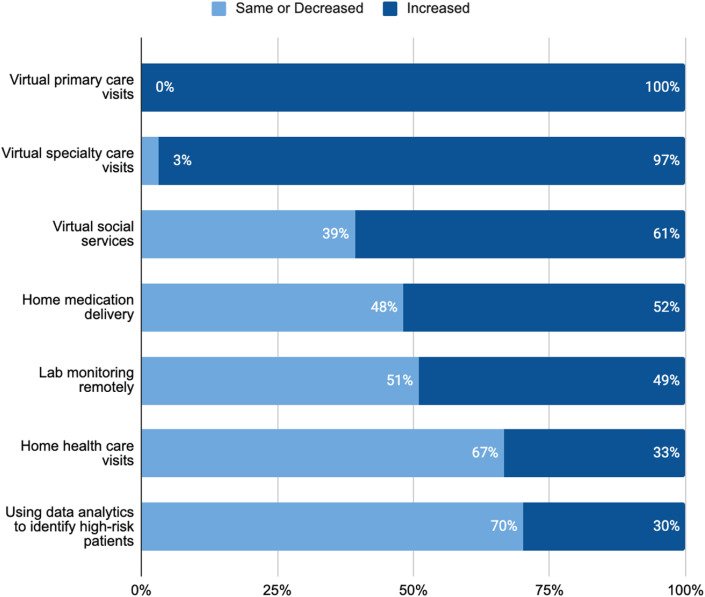

ACOs employed a variety of initiatives to address their concerns for these patients (Fig. 2 ). All ACO respondents (100%) reported using data analytics to identify high-risk patients. Compared to before the pandemic, some ACOs relied more on data analytics (30%) (Fig. 3 ). One ACO specifically noted making phone calls to these patients, and another reported using real-time data from admission, discharge and transfer (ADT) feeds to flag COVID-19 patients.

Fig. 2.

ACOs Are Using Virtual and Home Care Strategies to Meet Patient Needs

Which strategies are used to meet needs of older patients with multiple chronic conditions?

Fig. 3.

ACOs Are Increasing Use of Certain Services Compared to Before the Pandemic.

If offered, has use of this strategy for these patients changed from before the pandemic?

4.2. Virtual services

Despite almost unanimous concerns regarding access to social services, 39% of ACO respondents reported not offering patients virtual social services. Among those that were making virtual social services accessible, 61% reported use had increased from before the pandemic.

All ACOs reported using virtual primary care visits for at least some of their patients and that use of virtual primary care had increased from the period before the COVID-19 pandemic. Similarly, 95% of ACO respondents used virtual specialty care visits and 97% were using virtual specialty care more than they had been before the pandemic.

4.3. Medications and lab monitoring

Home medication delivery and remote lab monitoring (which includes performing tests in the home or community) were relatively less common, with about 30% of ACO respondents reporting not using either at all. Among the 69% using home medication delivery, majority (60%) were using this service for just some patients. Half (52%) increased use of home medication delivery from before the pandemic. For the 70% of ACO respondents using remote lab monitoring, about half (49%) had increased use from baseline. One ACO specifically noted using patient monitoring for vital signs including blood pressure.

4.4. Home health care service visits

More than three-quarters (77%) of ACO respondents were using home health care visits, with 21% reporting most patients are using them. Compared to other strategies, relatively fewer ACOs were scaling up home health care service visits, and 15% of ACO respondents reported decreased utilization of home health care compared to before COVID-19.

5. Discussion

ACO leaders expressed major concerns about access to needed care for older adults with multiple chronic conditions during the COVID-19 pandemic, especially accessibility of social services, such as food assistance, and long-term care services. Their worry is particularly meaningful given ACOs may be better prepared than other clinical organizations to coordinate and adapt high-quality care for this population. To deal with the disruptions caused by the pandemic, nearly all ACOs reported increased use of virtual primary care and specialty care visits; however, other services such as virtual social services, home medication delivery, and remote lab monitoring were far less commonly accessible. These findings, along with the descriptive responses from ACOs about what additional support is needed, highlights key priorities areas for improving routine care for older adults with multiple chronic conditions during the COVID-19 pandemic.

First, supporting organizations in identifying effective ways to meet social needs virtually is critical. Though nearly all ACOs reported concerns about access to social services such as food assistance or legal services, 39% of ACO respondents were not offering virtual social services. The majority of ACOs that were providing such services had increased their use from baseline, suggesting many ACOs tried to adapt to meet this need. Of note, ACOs likely were most commonly making these services accessible through partnerships, not building out these services directly. Prior to the pandemic, some healthcare organizations were pursuing innovative ways of addressing individual-level social determinants of health for patients, including providing meals, offering temporary housing, addressing environmental triggers like mold at home, or offering legal support for immigration matters. Yet sustaining such interventions virtually may present challenges, such as patients having limited technology access, health professionals having limited experience with virtual services, or social services organizations reducing their workforce size during the economic downturn. Further research on effective approaches to meeting social needs virtually is key, including publicly describing strategies being tested as some ACOs have done during the pandemic, as well as working with community-based organizations to reach newly homebound adults [11]. Policy options to consider may include payors offering reimbursement for social services (e.g. following the example of North Carolina's Healthy Opportunities Pilot program in the Medicaid program) or better facilitating direct communication between health care and social service organizations[12].

Second, despite nearly all ACOs growing their use of virtual visits, numerous barriers need to be addressed to enable better access to telehealth. In an open response question asking about ways to enable better care for older adults with multiple chronic conditions, 22 ACOs reported needs related to making telehealth services more accessible. Most of these ACOs reported that patient-related barriers to virtual visits were major challenges, including poor WiFi connections among lower socioeconomic status and rural patients and limited ability to navigate digital devices among older patients. For example, one ACO wrote, “[A] major issue is that older patients with chronic conditions have limited ability to figure out how to use the telemedicine programs our clinics are using … and most of these patients lack smartphones to use programs such as FaceTime.” Desired solutions raised by ACOs in our sample included funding to provide smartphones with strong data plans to high-risk patients, policies to more broadly invest in digital access for communities, and better training tools and visual aids to teach patients how to use telehealth platforms.

Third, multiple ACOs reported a need for better remote monitoring capability. These included the ability to measure vital signs, weights, and glucose levels from home. For instance, one ACO wrote, “[We need] more access to devices and …. more remote monitoring capacity to get vitals, weights, sugars, [and more].” Nearly one-third of ACOs were not using remote lab monitoring (i.e. performing blood and other lab tests at home or in the community that then get updated into their electronic health systems), which may hamper the ability of clinicians to adequately manage patient's chronic conditions like diabetes or hypertension during virtual visits. For example, titrating medications during a primary care virtual visit may be challenging. Though payer policies reimbursing patients for home monitoring devices might prove beneficial to population health efforts, evidence of such trends so far is limited.

Fourth, nine ACOs described a need for greater funding or resources to invest in new care delivery models. These ACOs reported that limited financial capital hampered the organization's ability to adapt to virtual care and use virtual services effectively for patient care. For example, one ACO wrote, “[We need] improved payments … to support retention of staff, considering unemployment payments are often higher than wages … particularly when considering child care costs if working full-time.” Another ACO wrote, “[We need] parity payment for telehealth visits so our clinics can keep their doors open.” Despite a desire to provide remote monitoring services, some indicated the lack of reimbursement for these services limited their use. In addition, multiple ACOs described that primary care clinics are receiving insufficient pandemic-related financial support while large and relatively wealthy health systems receive more federal funding, consistent with calls from some ACOs for dedicated Congressional funding for primary care groups [13].

4.1. Limitations

This survey has several limitations. The sample is not generalizable to all ACOs, though to our knowledge, it is currently the largest known ACO survey about routine care for older adults with multiple chronic conditions during the pandemic. Second, as with any survey, it is possible that the views of the survey respondents, who were identified as the lead ACO contacts by CMS, may differ slightly than other members of the organization.

5. Conclusion

ACOs, which were organized before the pandemic to provide population health services for high-risk patients, reported consistent concerns about routine care for older adults with multiple chronic conditions. This survey of ACOs highlights the need for efforts to better support delivery organizations in meeting the needs of this population, including bolstering support for virtual social services, addressing barriers to making telehealth accessible to more patients, promoting capacity for remote vital sign and lab monitoring, and increasing funding available for piloting new virtual and home delivery models. As Medicare ACOs may well represent a best-case scenario for population management for older adults, their concern should motivate action from policymakers and payers to support all organizations in addressing these barriers.

Disclosures

ALB reports receiving consult fees from Aledade Inc. unrelated to this work and being formerly employed there. JFF reports receiving grants for other work from the Commonwealth Fund and the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation. REM reports that the Institute for Accountable Care receives financial support from the National Association of ACOs. TSB is fully funded through the Commonwealth Fund.

Funding

The authors of this work receive funding from the Commonwealth Fund.

Declaration of competing interest

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

| ACOs Are Concerned About Older Patients with Chronic Conditions Not Receiving Essential Social And Medical Care |

|---|

| How concerned are you that these patients will not get the service when they need it? |

| ACOs Are Using Virtual and Home Care Strategies to Meet Patient Needs |

|---|

| Which strategies are used to meet needs of older patients with multiple chronic conditions? |

| ACOs Are Increasing Use of Certain Services Compared to Before the Pandemic |

|---|

| If offered, has use of this strategy for these patients changed from before the pandemic? |

References

- 1.KFF Health Tracking Poll – Health and Economic Impacts [Internet]. KFF. 2020. May 2020. https://www.kff.org/report-section/kff-health-tracking-poll-may-2020-health-and-economic-impacts/ 2020 Jun 16];Available from:

- 2.Solomon M.D., McNulty E.J., Rana J.S., et al. N Engl J Med; 2020. The Covid-19 Pandemic and the Incidence of Acute Myocardial Infarction. Available from: [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kansagra A.P., Goyal M.S., Hamilton S., Albers G.W. N Engl J Med; 2020. Collateral Effect of Covid-19 on Stroke Evaluation in the United States. Available from: [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.What Impact Has COVID-19 Had on Outpatient Visits? |Commonwealth Fund. 2020 jun 16. https://www.commonwealthfund.org/publications/2020/apr/impact-covid-19-outpatient-visits Available from: [Google Scholar]

- 5.fabrice, Administrator K.C., Lucas L., Alan Yim J. https://www.ehrn.org/delays-in-preventive-cancer-screenings-during-covid-19-pandemic/ Delayed Cancer Screenings – Epic Health Research Network [Internet]. Epic Health Research Network. 2020 [cited 2020 Jun 16];Available from:

- 6.McWilliams J.M., Hatfield L.A., Landon B.E., Hamed P., Chernew M.E. Medicare spending after 3 Years of the Medicare shared savings program. N Engl J Med. 2018;379(12):1139–1149. doi: 10.1056/NEJMsa1803388. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.How ACOs Are Caring for People with Complex Needs |Commonwealth Fund. 2020 Jun 16. https://www.commonwealthfund.org/publications/fund-reports/2018/dec/how-acos-are-caring-people-complex-needs Available from: [Google Scholar]

- 8.Murray G.F., Rodriguez H.P., Lewis V.A. Upstream with A small paddle: how ACOs are working against the current to meet patients' social needs. Health Aff. 2020;39(2):199–206. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.2019.01266. Available from: [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Romm I., Ajayi T. Weaving whole-person health throughout an accountable care framework: the social ACO. Health Affairs Blog, January. 2017;25 https://www.healthaffairs.org/do/10.1377/hblog20170125.058419/full/ Available from: [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ikram U., Gallani S., Figueroa J., Feeley T. Protecting vulnerable older patients during the pandemic. NEJM Catalyst. September. 2020;17 Available from: https://catalyst.nejm.org/doi/full/10.1056/CAT.20.0404. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Schnake-Mahl A., Carty M.G., Sierra G., Ajayi T. Identifying patients with increased risk of severe covid-19 complications: building an actionable rules-based model for care teams. NEJM Catalyst. May 4, 2020 https://catalyst.nejm.org/doi/full/10.1056/CAT.20.0116 Available from: [Google Scholar]

- 12.Wortman Z., Tilson E.C., Cohen M.K. Buying health for North carolinians: addressing nonmedical drivers of health at scale. Health Aff. 2020;39(4):649–654. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.2019.01583. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Slavitt A., Mostashari F., Sebenius I., et al. https://www.statnews.com/2020/05/28/covid-19-battering-independent-physician-practices/ Covid-19 is battering independent physician practices - STAT [Internet]. STAT. 2020 [cited 2020 Jun 19];Available from: