COVID-19 holds the world in a tight grip. In these unprecedented times, health and health-system capacities have been on the top of the global agenda for several months. Many countries have rolled out far-reaching prevention measure such as physical distancing and ‘lock-downs’ to prevent (further) overwhelming of health system capacities.

In many contexts, people who use drugs are a vulnerable population, prone to poor access to health services compounded by criminalization, and stigmatisation in health-care settings (UNAIDS, 2019; Van Boekel, Brouwers, Van Weeghel & Garretsen, 2013). This is illustrated in poor health outcomes and persisting high risk of infectious diseases. For instance, people who inject drugs are left behind in the progress of the global HIV response with less than 1% living in a country with high level of critical prevention services, such as access to sterile syringes and low-threshold opioid treatment programmes or opioid agonist therapy (OAT) (UNAIDS, 2019; Larney et al., 2017).

At the time of writing, no data or reports have emerged on specific COVID-19 outbreaks amongst communities of people who use drugs. While pre-existing health issues, such as lung conditions, may enhance the vulnerability to COVID-19 of some people who use drugs, there is currently limited data available on its specific direct impact on people who use drugs (EMCDDA, 2020; Harris, 2020). However, the indirect impact of overloaded health-structures and changing health service delivery schemes, due to COVID-19 related prevention measures, can be expected to particularly affect vulnerable communities such as people who use drugs (Dunlop et al., 2020).

A recent commentary in this journal proposed that the direct and indirect effects of COVID-19 should be approached in a ‘complex adaptive systems’ approach (Grebely, Cerda & Rhodes, 2020). Such an approach understands health as contingent and emergent, in which multiple social, structural, environmental and cultural factors entangle, and in which social and health systems adapt in response. In this editorial, we explore the impacts of COVID-19 on people who use drugs in a ‘health systems’ perspective. We argue that COVID-19 prevention measures, aiming to protect health systems from being overwhelmed, create additional challenges to access prevention and care for people who use drugs, but also create opportunities to break through existing barriers to prevention and health service delivery.

Vulnerable communities in a health system under pressure

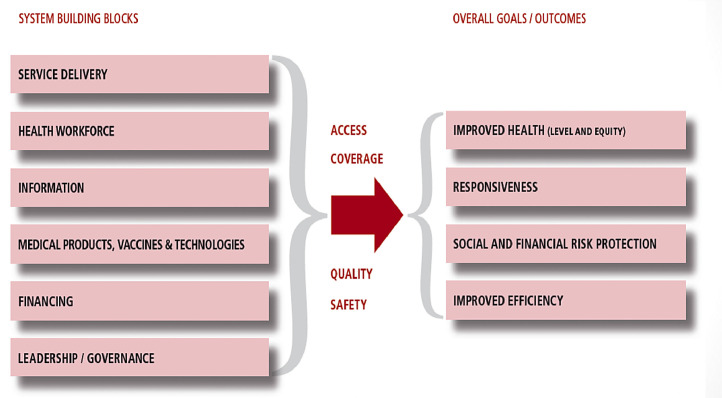

Extensive pressure on health systems can lead to reduced health outcomes (McQuilkin, Udhayashankar, Niescierenko & Maranda, 2017). The WHO health system framework (Fig. 1 ) illustrates how the extent of the COVID-19 pandemic impacts multiple aspects (building blocks) of a health system (World Health Organization, 2007). Insufficient health workforces, lack of medical products (such as personal protection equipment and ventilators) are just some of the health system building blocks challenges in 2020. Furthermore, over-burdening one component of the system, interacts with and impacts other health system components. For instance, an insufficient health workforce could ultimately lead to paralysation (or deprioritise) certain service deliveries of the system. Following the logic of the framework, this would inevitably result in reduced overall health outcomes, beyond direct COVID-19 related care. This has been one of the valuable retrospective lessons learned from the 2013–2016 West Africa Ebola outbreak (Wilhelm & Helleringer, 2019).

Fig. 1.

The WHO building blocks framework(10).

Marginalised and criminalised communities have greater challenges accessing health services (UNAIDS, 2019). Consequently, a health system under too much pressure would likely disproportionally impact people with already established barriers, such as people who use drugs. Looking back at the conceptual building block framework, the notion of equity has been explicitly integrated in the goals of improved health outcome. This underlines that perhaps health systems have a tendency to ‘serve the mass’, and additional attention is needed to ensure equitable access for all, including criminalised and marginalised communities such as people who use drugs (United Nations Human Rights & OHCHR, 2020).

In times of extremely burdened health systems, multiple (informal) reports come to the surface in grey literature and public webinars of concerning additional constraints in health and prevention services for people who use drugs, such as (temporary) closure of Harm Reduction services, restrictions in new enrolments for OAT and/or HCV treatment programs and reduced needle and syringe programs (UNAIDS, 2020a; UNODC, WHO, HRI, INPUD, EUROPUD, 2020b; Bartholomew, Nakamura, Metsch & Tookes, 2020; Whitfield, Reed, Webster & Hope, 2020). This is in stark contrast to international recommendations to sustain access to opioid agonist therapy and needle and syringe provision as an essential public health intervention for people who use drugs (United Nations Human Rights & OHCHR, 2020; EMCDDA, 2020).

The shock of a crisis; a ‘masked’ opportunity?

In times of crisis, routine decision-making goes beyond the business-as-usual and generates a window of opportunity to permit meaningful re-consideration of long debated policies (Buse, Mays & Walt, 2005). This could be reflected in the following conceptual theories.

Firstly, one of the six health system's building blocks defines the role of governance leadership and stewardship. In the case of policy development for people who are using illegal substances, this stewardship role exceeds the immediate scope of health agencies. Indeed, ministries of health will need to negotiate and collaborate on issues that overlap, or sometimes seemingly contradict, the mandate of other ministries. Law-enforcing policies in regards to people using illicit substances have often been a major barrier to enhance health driven policies. A shock to the system, due to covid-19, could potentially shift established boundaries and the jurisdictions of health policy makers.

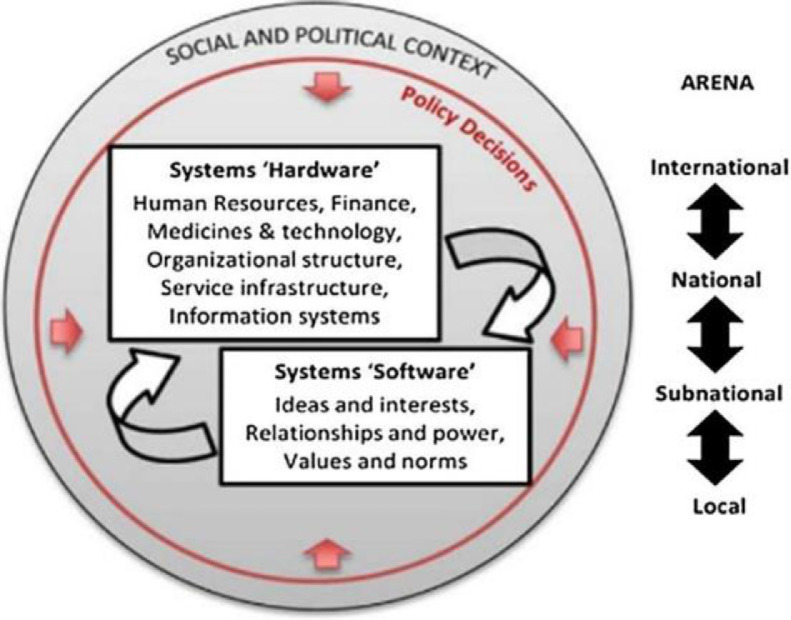

Secondly, the hardware / software framework (Fig. 2 ) captures how policy making, sometimes mistakenly seen as a linear ‘input-output’ model, is in fact heavily dependant on human factors such as ideas, relationships, morality and values (Sheikh et al., 2011). This is particularly relevant in light of policy making around people who use illicit substances, which is often trapped in morality driving policy-making, beyond scientific arguments (Fedotov, 2016).

Fig. 2.

The hardware/software framework(16).

The sudden shock of COVID-19 could on one hand strengthen the leverage of the health authorities in the discussion space with other ministries, while on the other hand it could amplify pragmatism instead of moralism in policy making process. By means of illustration, the shock of the HIV epidemic in the 1980s unquestionably contributed to the start of a radical paradigm shift in policies for people who use drugs, leaving space for pragmatic, health-orientated harm reduction responses over established repressive security driven strategies (O'Hare, 2007). This same principle is notable in relation to COVID-19 in the following three examples.

Prison release; why are they there in the first place?

The so-called ‘war on drugs’ has a devastating impact on health outcomes of people who use drugs. It is estimated that 20% of the global prison population is related to drug offences and the WHO recommends polices towards decriminalization of drug use and possession for personal use (Branson & Henrique, 2020; WHO, n.d., 2000; WHO, 2016).

Under the current circumstances, prisons are of particular concern. Compared to the general population, over five times higher case rates have been reported in the USA (Saloner, Parish, Ward, Dilaura & Dolovich, 2020). Overcrowding and lack of self-isolation in case of infection, are amongst many factors magnifying health-risks and in particular to COVID-19 (WHO & UNAIDS, 2020). Multiple countries such as Iran, Turkey, France, Myanmar and many others have rolled out prison release schemes, including people with non-violent offences, such as drug use. These instant release schemes contribute to the global debate on why people who use drugs are imprisoned in the first place.

Whilst these developments may fall outside of the traditional view of the health domain, one could argue that these actions with ‘a primary intention to improve health’, clearly mirror the definition of health systems (World Health Organization, 2007). In other words, current unique circumstances perhaps reflect in some ways an enhanced stewardship role of ministries of health in a policy area that is usually subjugated by ‘security-minded’ ministries.

Multiday prescriptions of opioid agonist therapy, at last.

As a second illustration of the potential opportunities of the current COVID-19 era, grey literature suggests a significant break-through in the deadlock of low threshold opioid agonist therapy schemes such as multiday prescriptions, in several countries including Morocco, Myanmar, Vietnam, Bangladesh, Iran, Nepal and India (UNODC, WHO, HRI, INPUD, EUROPUD, 2020b; UNAIDS, n.d., 2000; UNAIDS, 2020b; UNODC, WHO, HRI, INPUD, EUROPUD, 2020a; INPUD, 2020; Crowley & Delargy, 2020; WHO, 2009).

For many years, the WHO has recommended take-home doses for people who are stable on their opioid treatment prescriptions (WHO, 2009). However globally the dominant approach to methadone delivery remains via daily direct observational therapy, hereby undermining the true potential of this essential health service.

Despite years of opposition, under the current circumstances, in order to reduce overcrowding at delivery stations, strong governance from ministries of health have led to endorsing rapid take home dosing schemes. This is a tremendous leap forwards in a deadlock around person-centred and evidence-based service provision and was unthinkable only a few months back.

From a system thinking perspective, this could potentially illustrate a shift of priorities in the equation of ideas and values in health systems, as conceptualised in the hardware/software framework.

No health system, without us

Lastly, beyond these system thinking principles and conceptual models, one could argue that the current context shakes up the very understanding of the boundaries of health systems itself.

Community involvement has been endorsed for decades as an essential part of health programming (UNODC UNAIDS UNFPA WHO USAID PEPFAR, 2017). However the practical implementation of community involvement and peer driven service provision are unfortunately still far too often perceived as a supporting supplement (a cheaper alternative) or is practically implemented as a tokenistic shell-case to theoretically comply with the rights of the community.

The current context explicitly spotlights more than ever that the community plays a pivotal role in providing essential harm reduction services in a context with shifting delivery models and where established service models are failing. In response to COVID-19, people who use drugs have provided peer support through food- and financial aid, health and prevention services including secondary needle and syringe distribution, home delivery of medical treatment and preventing opioid overdoses (INPUD, 2020; UNODC, WHO, HRI, INPUD, EUROPUD, 2020a).

The WHO defines the boundaries of a health system as “all organizations, people and actions whose primary intent is to promote, restore and maintain health” (World Health Organization, 2007). The community of people who use drugs have once again made it abundantly clear that their involvement should not be perceived on the margins of health programming, but should be incorporated as an inherent component of health systems (Chang, Agliata & Guarinieri, 2020).

Too fast too furious?

Certainly, the examples provided are exclusively context dependant and could hardly be used to project definite progress on a global scale. Many places are in fact reducing access to opioid agonist therapy and are exacerbating punitive law-enforcement approaches towards criminalised and marginalised communities, with movement restrictions further magnifying vulnerability factors. Certainly, each context individually represents its own set of challenges and in the complex equation of positive or negative outcomes, COVID-19 prevention measures might rarely balance out in an overall progression of health for people who use drugs.

Reports on COVID-19 prison decongestion measures indicate they have fallen far short of expectations, with less than 6% of the global prison population being released (as of June 2020). Additionally, a significant proportion of countries explicitly excluded people in prison for drug offences from release (HRI, 2020).

Moreover, nothing indicates today that any of those initiative would be lasting in any way. Will it all go back to normal in a few months? The rapid shift towards take-home dosing, can just as rapidly be turned back. Community involvement can as easily be forgotten in future health programming and releasing prisoners out of a sudden emergency public health response does not necessarily make a lasting change for new people being put in prison for non-violent drug related crimes.

Seizing opportunities

The COVID-19 pandemic has a profound effect on the provision of health services across the globe and exacerbates the existing barriers to health faced by people who use drugs. However, emerging literature suggests some unprecedented shifts in favour of enhanced opioid treatment provision models and renewed opportunities to strengthen the case of community involvement and decriminalisation of people who use drugs on the global agenda.

The documented positive changes, so far, seem to have emerged entirely from within national interest and under full leadership and ownership of national governments. Reflecting back to the earlier mentioned ‘hardware/software’ framework on health systems (Fig. 2), (Sheikh et al., 2011), the model recognises the influence of the social and political context, as well as the interaction and involvement of international, national, subnational and local interest and actors. This could perhaps highlight the important role that international stakeholders could play to preserve the recent progressive national developments and potentially encourage similar initiatives in other settings.

Decades of inhumane policy development has passed on the lesson to seize the moment however challenging the times might be. We would argue that this has grown into an inherent strength of the harm reduction movement and highlight the potential opportunity to leverage the current times to achieve a lasting, rather than merely temporary, leap forward.

Declarations of Interest

None

References

- Bartholomew T.S., Nakamura N., Metsch L.R., Tookes H.E. Syringe services program (SSP) operational changes during the COVID-19 global outbreak. International Journal of Drug Policy. 2020 doi: 10.1016/j.drugpo.2020.102821. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Branson, R., & Henrique, F. (2020). Enforcement of drug laws. Retrieved from https://www.globalcommissionondrugs.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/04/FINAL-EN_2020report_web.pdf

- Buse K., Mays N., Walt G. Making health policy (understanding public health) UK: Bell & Brain Ltd (2nd ed.) 2005 [Google Scholar]

- Chang J., Agliata J., Guarinieri M. COVID-19 - Enacting a ‘new normal’ for people who use drugs. International Journal of Drug Policy. 2020 doi: 10.1016/j.drugpo.2020.102832. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crowley D., Delargy I. A national model of remote care for assessing and providing opioid agonist treatment during the COVID-19 pandemic: A report. Harm Reduction Journal. 2020 doi: 10.1186/s12954-020-00394-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dunlop A., Lokuge B., Masters D., Sequeira M., Saul P., Dunlop G. Challenges in maintaining treatment services for people who use drugs during the COVID-19 pandemic. Harm Reduction Journal. 2020;17:26. doi: 10.1186/s12954-020-00370-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- EMCDDA. (2020). EMCDDA update on the implications of COVID-19 for people who use drugs (PWUD) and drug service providers. Retrieved May 22, 2020, from https://www.emcdda.europa.eu/system/files/publications/12879/emcdda-covid-update-1-25.03.2020v2.pdf

- Fedotov, Y. (2016). UNODC Chief: Disproportionate responses to drug related offences do not serve justice, or uphold rule of law. Retrieved May 24, 2020, from 15 march 2016 website: https://www.unodc.org/unodc/en/frontpage/2016/March/unodc-chief_-disproportionate-responses-to-drug-related-offences-do-not-serve-justice–or-uphold-rule-of-law.html

- Grebely J., Cerda M., Rhodes T. COVID-19 and the health of people who use drugs: What is and what could be? International Journal of Drug Policy. 2020;(83) doi: 10.1016/j.drugpo.2020.102958. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harris M. An urgent impetus for action: Safe inhalation interventions to reduce COVID-19 transmission and fatality risk among people who smoke crack cocaine in the United Kingdom. International Journal of Drug Policy. 2020 doi: 10.1016/j.drugpo.2020.102829. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- HRI. (2020). COVID-19, Prisons and Drug Policy. Retrieved July 21, 2020, from Harm Reduction International website: Https://www.hri.global/covid-19-prison-diversion-measures.

- INPUD. (2020). Inpud online survey on COVID-19 & people who use drugs (PWUD) data report 1 June 2020 inpud online survey on COVID-19 & people who use drugs (PWUD) data report 1 June 2020. Retrieved from https://www.inpud.net/sites/default/files/INPUD_COVID-19_Survey_DataReport1.pdf

- Larney S., Peacock A., Leung J., Colledge S., Hickman M., Vickerman P. Global, regional, and country-level coverage of interventions to prevent and manage HIV and hepatitis C among people who inject drugs: A systematic review. The Lancet Global Health. 2017;5(12):e1208–e1220. doi: 10.1016/S2214-109X(17)30373-X. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McQuilkin P.A., Udhayashankar K., Niescierenko M., Maranda L. Health-care access during the Ebola virus epidemic in Liberia. American Journal of Tropical Medicine and Hygiene. 2017;97(3):931–936. doi: 10.4269/ajtmh.16-0702. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O'Hare P. Merseyside, the first harm reduction conferences, and the early history of harm reduction. International Journal of Drug Policy. 2007 doi: 10.1016/j.drugpo.2007.01.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saloner B., Parish K., Ward J.A., Dilaura G., Dolovich S. COVID-19 cases and deaths in federal and state prisons. Journal of the American Medical Association. 2020 doi: 10.1001/jama.2020.12528. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sheikh K., Gilson L., Agyepong I.A., Hanson K., Ssengooba F., Bennett S. Building the field of health policy and systems research: Framing the questions. PLoS Medicine. 2011;8(8) doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.1001073. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- UNAIDS. (n.d.). COVID-BLOG - Ensuring that all people who use drugs and are living with HIV have access to treatment in Bangladesh (2000). Retrieved from https://www.unaids.org/en/20200430_Bangladesh_pwud

- UNAIDS Health, rights and drugs - harm reduction, decriminalization and zero discrimination for people who use drugs. In Health, rights and drugs - harm reduction, decriminalization and zero discrimination for people who use drugs. 2019 http://proxy.lib.umich.edu/login?url=http://search.ebscohost.com/login.aspx?direct=true&db=lhh&AN=20193383307&site=ehost-live&scope=site%0Ahttps://www.unaids.org/sites/default/files/media_asset/JC2954_UNAIDS_drugs_report_2019_en.pdf Retrieved from. [Google Scholar]

- UNAIDS. (2020a). COVID-BLOG - Assisting people who use drugs to receive methadone treatment during COVID-19 lockdown in Kazakhstan. Retrieved May 22, 2020, from 24 april website: https://www.unaids.org/en/20200424_Kazakhstan_ost

- UNAIDS. (2020b). COVID-BLOG - Ensuring continuity of methadone maintenance therapy for people who use drugs in Viet Nam. Retrieved May 22, 2020, from 24 april website: https://www.unaids.org/en/20200424_VietNam_MMT

- United Nations Human Rights, & OHCHR. (2020). Statement by the UN expert on the right to health* on the protection of people who use drugs during the COVID-19 pandemic. Retrieved May 22, 2020, from http://www.ohchr.org/RU/NewsEvents/Pages/DisplayNews.aspx?NewsID=13206&LangID=E

- UNODC, WHO, HRI, INPUD, EUROPUD, M. (2020a). COVID-19 and Harm Reduction Programme Implementation: Sharing Experiences in Practice - Webinar #1. Retrieved from https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=MbdwoQPz-h4&feature=youtu.be

- UNODC, WHO, HRI, INPUD, EUROPUD, M. (2020b). COVID-19 and Harm Reduction Programme Implementation: Sharing Experiences in Practice - Webinar #2. Retrieved from https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=VT5C16qMt04&feature=youtu.be

- UNODC UNAIDS UNFPA WHO USAID PEPFAR. (2017). Implementing Comprehensive HIV and HCV Programmes with People Who Inject Drugs. Retrieved from https://www.inpud.net/sites/default/files/IDUIT 5Apr2017 for web.pdf

- Van Boekel L.C., Brouwers E.P.M., Van Weeghel J., Garretsen H.F.L. Stigma among health professionals towards patients with substance use disorders and its consequences for healthcare delivery: Systematic review. Drug and Alcohol Dependence. 2013;131:23–35. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2013.02.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Whitfield M., Reed H., Webster J., Hope V. The impact of COVID-19 restrictions on needle and syringe programme provision and coverage in England. International Journal of Drug Policy. 2020 doi: 10.1016/j.drugpo.2020.102851. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- WHO. (2016). Policy Brief Hiv Prevention, Diagnosis, Treatment and Care for Key Populations. [PubMed]

- WHO WHO | Consolidated guidelines on HIV prevention, diagnosis, treatment and care for key populations. In WHO. Retrieved from World Health Organization website: 2000 https://www.who.int/hiv/pub/guidelines/keypopulations-2016/en/ [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- WHO Guidelines for the psychosocially assisted pharmacological treatment of opioid dependence. Retrieved from. 2009 http://books.google.com/books?hl=en&lr=&id=yKV6i3ZK86kC&oi=fnd&pg=PP2&dq=Guidelines+for+the+Psychosocially+Assisted+Pharmacological+Treatment+of+Opioid+Dependence&ots=NtatF6p9lt&sig=batQx8UMQBGw-HWDpEa3XFwrj00%5Cnhttp://books.google.com/books?hl=en&lr=&id [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- WHO, Un. O., & UNAIDS. (2020). UNODC, WHO, UNAIDS AND OHCHR joint statement on COVID-19 in prisons and other closed settings*. Retrieved from https://www.unodc.org/documents/Advocacy-Section/20200513_PS_covid-prisons_en.pdf

- Wilhelm J.A., Helleringer S. Utilization of non-Ebola health care services during Ebola outbreaks: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Journal of Global Health. 2019;9(1) doi: 10.7189/jogh.09.010406. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- World Health Organization. (2007). Everybody's business strengthening health systems to improve health outcomes - WHO's framework for action.