Summary

Introduction

In the early phase of the coronavirus disease (COVID-19) epidemic in France, knowledge of SARS-COV-2 characteristics was limited, and personal protective equipment (PPE) was lacking. Thus, health care workers (HCWs) were exposed to nosocomial transmission.

Methods

A multicenter regional descriptive study of fifty-two heath care facilities covering 30,533 HCWs in western Normandy, France, from March 3 to March 27, 2020, before the incidence threshold of 10/100,000 inhabitants was crossed in the study area. The incidence rate of COVID-19 in HCWs, the attack rates and the serial interval distribution of nosocomial transmission were computed. Demographic characteristics of HCWs, contacts with index cases, and the use of personal protective equipment were collected by a structured questionnaire.

Results

The incidence rate of COVID-19 in HCWs was 2.7‰. Among 19 situations (13 clusters >2 cases), 10 were HCW-HCW and 9 patient-HCW transmission, the global attack rate was 13.7% (95% confidence interval, 10.6%–17.3%), and 68 HCWs were involved (10 index cases, with 58 secondary cases). Exposure of secondary cases was only in the presymptomatic phase of the index case in 29% of cases, 48% for HCW-HCW and 10% for patient-HCW transmission (P<0.001). The mean serial interval was 5.1 days (95% CI, 4.2–5.9 days). Preventative measures were not optimal.

Conclusions

Our investigation demonstrated that HCWs who were not assigned to the care of COVID-19 patients were not prepared for the arrival of this particularly insidious new virus, which spread rapidly from an often asymptomatic colleague or patient.

Keywords: Coronavirus disease 2019, Health care workers, Healthcare associated infections, France

Introduction

The world faces a global pandemic due to SARS-CoV-2, a novel betacoronavirus causing coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) first reported in November 2019 in people exposed to a seafood wholesale market in Wuhan, China [1]. European countries became the epicenter of the epidemic in mid-March 2020. In France, the first imported cases were identified on 24 January 2020 [2]. Rapidly, new cases and clusters appeared, leading to a national lockdown on 17 March 2020.

At first, knowledge of the modes of transmission and the clinical profile of infections caused by this emerging virus was limited, and personal protective equipment (PPE) was lacking. In France, maximalist measures were adopted for the management of patients suspected of or suffering from COVID-19: droplet and reinforced contact precautions (isolation of patients, mask, eye protection, hair protection, isolation gown, and aprons). For the management of other patients, the measures recommended were standard precautions, with masks used in the event of respiratory symptoms in the health care worker (HCW) or the patient [3]. Faced with this new risk, HCWs remained mobilized: they were on the front line and occupationally exposed to the risk of nosocomial acquisition or transmission.

Subsequently, several important descriptive articles [[4], [5], [6], [7], [8], [9]] provided step-by-step essential information to better understand the virus transmission and to adapt precautions by numerous and successive protective measures. However, these articles rarely addressed the exposure and the modes of acquisition of COVID-19 by HCWs.

We report the results of a regional multicenter study, in which we exhaustively identified and described nosocomial transmissions of COVID-19 involving HCWs at an early stage of the epidemic in Normandy, France.

Material and methods

Location and period

The present study was conducted in the 3 departments (Calvados, Manche, Orne) of western Normandy, located in northwestern France, with 3,300,000 inhabitants, 52 health establishments (26 hospitals, 11 clinics, 11 rehabilitation and recuperative care facilities and 4 establishments specializing in psychiatry) and 30,533 HCWs.

The study period begins with the first case of COVID-19 observed in this area (03/04/2020) and ends with the cumulative incidence threshold-crossing date, which was 10/100,000 inhabitants in each of these areas: 03/19/20, Calvados; 03/21/20, Manche; and 03/27/20, Orne. This period was chosen to correspond to the epidemic phase II [10], during which Regional Health Agency and Infection prevention control teams conducted contact tracing, a procedure in which contact cases and transmission chains are identified for community and health facilities cases, respectively. Thus, the nosocomial origin of the cases included in the study could be certified. In the study area, cases increased exponentially since 03/04/20, with a doubling time of three days, and the 10/100,000 inhabitants threshold crossing was observed on 03/21/2020 (e-supplemental Figure 1).

Rights and ethics

A local ethics committee approved this present study (ID 1403). First, the agreement of each health establishment was requested, before contact with HCWs. Then, study investigators collected authorizations for each voluntary health care worker.

Data acquisition

To identify HCWs with confirmed COVID-19 and their nosocomial transmission during the study period, several data sources were cross-referenced:

-

A)

Direct contact with management teams, occupational medicine, human resources and the infection prevention and control teams of each establishment;

-

B)

The hospital virology laboratory of Caen, Normandy, which centralized real-time reverse transcriptase polymerase chain reaction (RT-PCR) tests for COVID-19 nucleic acid in the study area during this period [11]; RT-PCR tests were only performed in symptomatic patients with identification of a possible exposition, such as a trip in a zone with high COVID-19 incidence;

-

C)

A national external reporting nosocomial infections regulatory system [e-sin, 12] in which COVID-19 cases acquired in health establishments are reported.

For each nosocomial transmission situation identified, an in-depth investigation was carried out to identify an index case, secondary case(s) and the total number of contact cases. HCWs involved were contacted by an investigator to collect information using a structured questionnaire: occupation, age, sex, risk factors for severe COVID-19, first symptoms' date and types, contacts with COVID-19 suspected or proven persons outside of work, number of days with at least one exposure to the index case and daily duration of exposures (in hours) within 1 meter, barrier measures adopted during contact with patients and between HCWs, and number and description of contacts between HCWs (meetings, meals, …). The studied exposure period ran from 2 days before index case symptom onset to the day before home lockdown or discharge, transfer, or death, respectively, for the HCW and patient. Index case community acquisition circumstances were collected as additional information. Patient index cases' health care circuit and preventive barriers measures were also collected.

Cases definition

Nosocomial transmission situations were included if at least one COVID-19 HCW transmission case occurred from an index HCW case (HCW-HCW transmission) or from an index patient case (patient-HCW transmission). A minimum situation of 3 confirmed or probable cases (index case and secondary cases), within a period of 7 days, was defined as a cluster [10].

Cases were considered index cases if at least one COVID-19-positive RT-PCR test was confirmed and if the suspected origin of transmission was outside the establishment. Cases were considered secondary cases if a) at least one COVID-19-positive RT-PCR test was confirmed or clinical diagnosis was strongly suggestive (absence of available test), and b) at least one contact with the index case during his contagious period was confirmed (starting 2 days before symptom onset and ending the day before home lockdown or discharge of the index case), and c) no community acquisition was reported. Secondary cases were classified as “certain” if no other nosocomial transmission source was identified after questioning and as “possible” if another nosocomial transmission source was suspected (contact with another secondary case) or if the diagnosis was clinical only.

Statistical analysis

Situation and case characteristics were described, including demographic, exposure and prevention data. The incidence rate was calculated by dividing the number of confirmed COVID-19 cases by the total number of HCWs working for all 52 health care establishments [13]. The attack rate was calculated for each situation by dividing the number of secondary cases by the HCW's contacts with index case total number during the exposure window. Secondary case exposure with index case HCWs or patients were compared using the chi square test or Fisher's test and the Wilcoxon test, respectively, for qualitative and quantitative variables.

The serial interval (number of days between index case first symptom onset and secondary case first symptom onset) distribution was estimated by fitting a gamma distribution to the transmission pairs data after exclusion of the only negative value. Gamma distribution parameters were estimated by maximum likelihood method, and median and interquartile range (IQR: 1st quartile - 3rd quartile) of the serial intervals were obtained by a bootstrap method with 1,000 replications.

A P <0.05 was considered significant. The analyses were performed in R version 4.0.0 (R Development Core Team).

Results

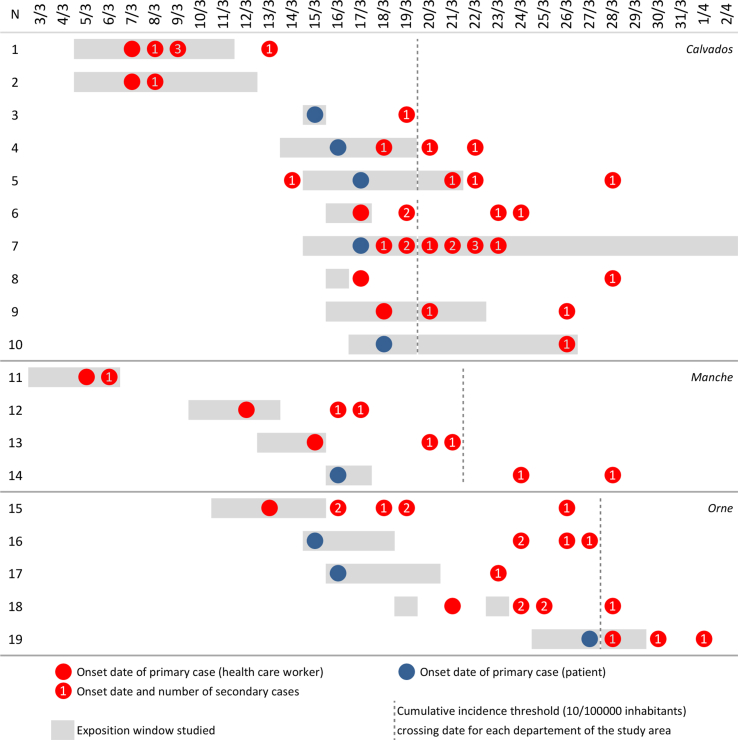

The 52 health care establishments in the study area participated, making it possible to identify 82 COVID-19 confirmed cases in HCWs, with 45 community cases (55%) and 37 nosocomial cases (45%). The overall incidence rate of COVID-19 in HCWs was 2.7‰ (82/30,533, 95% confidence interval (CI): 2.1‰–3.3‰, range: 0–64.2‰). Nineteen nosocomial transmission situations were identified, including 13 clusters covering 2 to 10 secondary cases (Figure 1 and e-supplemental Figures 2 and 3). These situations occurred in 14 different health establishments (27%), more frequently in hospitals (12/26, 46%) than in other establishments (2/26, 8%, P<0.001).

Figure 1.

Synoptic representation of nosocomial transmission situations, March 2020, western-Normandy, France. Nineteen situations and 58 pairs. The studied exposure window ran from 2 days before index case symptom onset to the day before home lockdown or the discharge, transfer, or death, respectively, for the HCW and the patient.

Ten situations (53%) were HCW-HCW transmission, and 9 (47%) were patient-HCW transmission, both generating 29 secondary transmissions. In HCW-HCW transmissions, the origin of community acquisition in the index case was well-identified 7 times (contacts at risk in a gymnastics club, choir, music lessons, and a trip to Paris), and more difficult to specify for the 3 others. These nosocomial situations occurred in care units (N=5), laboratories (N=3), and external consultations (N=2). In patient-HCW transmissions, two circumstances of transmission were identified: either the accidental discovery of COVID-19 in the index case during hospitalization (N=5: 4 times in rehabilitation, and 1 time in surgery) or hospitalization for acute pathology without immediate mention of the diagnosis of COVID-19 (N=4: 2 times in cardiology for chest pain and dyspnea and 2 times in medicine for infectious syndrome). For all the HCWs having had a risk exposure with an index case, the attack rate was 13.7% (95% CI: 10.6%–17.3%, range 3.4%–41.7%) (e-supplemental Table 1). For the majority of the situations (10/19, 53%), tertiary cases in HCWs and patients were subsequently identified, leading to complex situations with many chains of transmission.

Among the 68 HCWs involved in the 19 situations (10 index cases and 58 secondary cases, including 27 classified as certain), 58/68 (85%) were women, the median age was 41 years, 6/68 (9%) were physicians, 30/68 (44%) nurses, 21/68 (31%) assistant nurses, 6/68 (9%) laboratory technicians, 15/60 (25%) had a risk factor for severe SARS-COV-2 infection, 2/68 (3%) were hospitalized, and none died (e-supplemental Table 2).

The duration of the exposure window for secondary cases was 2.5 days on average, with a mean cumulative exposure time of 4 hours and no difference depending on the origin of the exposure (HCW or patient index case). The exposure of secondary cases took place only in the presymptomatic phase of the index case in 29% of cases (17/58), more frequently when the latter was a HCW (14/29, 48%) than a patient (3/29, 10%, P<0.001) (Table I).

Table I.

Exposition Window of Secondary Cases to Index Cases, March 2020, western-Normandy, France

| Exposition of SC (before their first symptoms) to IC | Total n=58 | Index case: HCW n=29 | Index case: patient n=29 | p |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Contacts, No. (%) | <0.001 | |||

| Only in presymptomatic phase of IC | 17 (29) | 14 (48) | 3 (10) | |

| Both in pre- and symptomatic phase of IC | 27 (47) | 14 (48) | 13 (45) | |

| Only in symptomatic phase of IC | 14 (24) | 1 (3) | 13 (45) | |

| Duration of contacts | ||||

| Days of work with at least 1 contact with IC (days), starting D-2 | ||||

| Mean (min-max) | 2.5 (0a-6.0) | 2.2 (0a-6) | 2.9 (1–5) | - |

| Median (IQR) | 2 (1–3) | 2 (1–3) | 3 (2–4) | 0.15 |

| Cumulated length of contact with IC (hours) during work, starting D-2 (md: 9) | ||||

| Mean (min-max) | 4.4 (0a-28.0) | 6.1 (0a-28.0) | 2.4 (0.2–12.0) | - |

| Median (IQR) | 2 (1–5) | 2 (1–8) | 1 (1–12) | 0.40 |

IC: index case SC: secondary case HCW: health care worker IQR: interquartile range md: missing data.

Contact with IC at D-3.

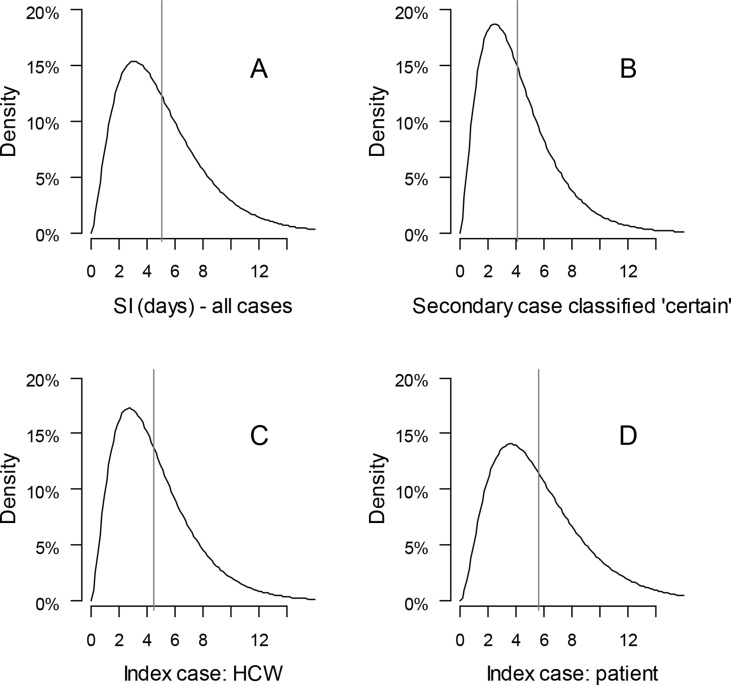

Based on 57 pairs of nosocomial transmissions (Figure 2), the estimates of the serial interval median were: a) 5.0 days (IQR 4.8–5.3) for all cases, b) 4.1 days (IQR 3.8–4.5 days) for cases classified as certain, c) 4.5 days (IQR 4.1–4.8 days) when the index case was a HCW and d) 5.7 days (IQR 5.2–6.1 days) when the index case was a patient (Figure 2). One serial interval was negative (-3 days).

Figure 2.

Serial interval estimates for nosocomial transmission cases, March 2020, western-Normandy, France. All cases (A, N = 57), cases classified as certain (B, N = 26), HCW-HCW transmissions (C, N = 29) and transmission patient-HCW (D, N = 28). One negative serial interval was excluded. The vertical lines represent the estimated mean. HCW=health care worker.

In HCW-HCW transmission, the systematic wearing of a face mask by the index case and secondary case was never reported (Table II). Professional contacts without a face mask during the day were frequent, with at least one occasion in 74% of cases (20/27). Contacts took place mainly during breaks (15/27, 56%), meals (12/27, 44%) and professional meetings (9/27, 33%). In patient-HCW transmissions, the face mask was systematically worn during contacts with patients in 42% of cases (11/26), but masks being worn by both the patient and the secondary case was never reported. The other personal protection elements were rarely used (isolation gowns or apron 4/26, 15%, eye protection and hair protection 1/26, 4%). In all cases of transmission, the HCWs declared that they regularly used hydroalcoholic solutions for hand disinfection.

Table II.

Preventive Measures Adopted by Secondary Cases in Contact with Index Cases, March 2020, western-Normandy, France

| Preventive measures before symptom onset | No. (%) |

|---|---|

|

HCW-HCW transmissions (N=29) – Preventive measures during work(md: 2) | |

| Face mask systematically worn | |

| By index cases | 2 (7) |

| By secondary cases | 2 (7) |

| By both index and secondary cases | 0 (0) |

| Use of alcoholic solution and hands washed with soap regularly | 27 (100) |

| HCW-HCW professional contacts without face mask | |

| At least 1 occasion | 20 (74) |

| Breaks | 15 (56) |

| Meals | 12 (44) |

| Professional meetings |

9 (33) |

|

Patient-HCW transmissions (N=29) – Preventive measures for contact with patients(md: 3) | |

| Mask worn for contacts, n (%) | |

| Face mask worn by secondary cases | 11 (42) |

| N95 mask worn by secondary cases | 0 (0) |

| Mask worn by both patient and secondary case | 0 (0) |

| Use of alcoholic solution and hands washed with soap regularly | 26 (100) |

| Isolation gown, apron for each contact | 4 (15) |

| Eye protection for each contact | 1 (4) |

| Hair protection for each contact | 1 (4) |

md: missing data.

Discussion

In the present study, we analyzed all SARS-COV-2 nosocomial transmission events in an area of 17,600 km2 in western France during phase II of the epidemic, an early period between the first reported case in the community and the incidence of 10/100,000 inhabitants (a 23-day period from 03/04/2020 to 03/27/2020). The phase II was ideally chosen to ensure confirmation of the transmission mode from a positive RT-PCR case to another and to obtain an exhaustive account. During this period of relatively low incidence in the population, nosocomial transmissions were observed in almost half of the hospitals, and the HCWs were almost equally infected from a colleague or a patient. Interestingly, we did not identify any transmission from index cases initially diagnosed with COVID-19, suggesting that in this case, services receiving these patients were well prepared.

Knowledge of the modalities of transmission of SARS-COV-2 has improved since the beginning of the pandemic with the publication of descriptive and experimental studies [4,6,14]. In the symptomatic phase of the disease, the main routes of transmission are well-known: droplet transmission, aerosols produced during invasive procedures and indirect (via contaminated surfaces) contact transmission [15,16]. In our study, we observed that the contacts causing the transmissions took place in the presymptomatic phase only of the index case in almost 30% of all cases and in almost 50% of the HCW-HCW transmissions. The possibility of transmission in the presymptomatic phase was mentioned quite early in the epidemic from different observations in Wuhan, China [17]. In addition, Zou et al. [18] demonstrated that the viral load observed in a patient who remained asymptomatic was as high as that in symptomatic patients. This active viral shedding and transmission were spectacularly confirmed as part of a comprehensive epidemiological investigation of a large cluster with a 64% attack rate that occurred in a skilled nursing facility in Washington State, United States [6]. It was notable that viable virus was isolated from samples 6 days before and up to 9 days after the onset of the first symptoms in residents. Presymptomatic transmissions can be considered the Achilles' heel of the strategies initially implemented to control SARS-CoV-2 [19], which replicated what had been successfully implemented in 2002–2003 to control the severe acute respiratory syndrome (SARS) epidemic caused by SARS-CoV-1, eradicated in 8 months after 8,100 cases. The existence of significant viral loads in the upper respiratory tract before and just after the onset of symptoms distinguishes SARS-CoV-2 from SARS-CoV-1, for which the maximum viral load is observed approximately 10 days after the first symptoms. In addition, we found a serial interval similar to those made on transmissions in the community [4,5,[20], [21], [22], [23]], close to or even less than the incubation period, estimated at approximately 5 days [5], again suggesting that some of the transmissions occur before the onset of symptoms.

The risk among HCWs has been the subject of several studies [[23], [24], [25], [26], [27], [28], [29]]. In February 2020, the Chinese Center for Disease Control and Prevention published a major report on more than 72,000 cases of COVID-19 [23]. HCWs represented 3.8% of confirmed cases (1716/44672), with 15% of severe cases and 5 deaths. In a large tertiary hospital with more than 7,000 beds in Wuhan, China, the contamination rate of HCWs was 1.1%, higher than that observed among inhabitants from the city of Wuhan (0.18%) [24], with a higher risk for HCWs not working in areas taking care of COVID-19 patients (incidence rate ratio: 3.1), explained mainly by delays in diagnosis in patients with atypical symptoms but also by the lack of PPE at the start of the epidemic management. Adapted and correctly applied prevention measures reduce the nosocomial risk for HCWs, as shown by a study of the seroprevalence in medical staff several weeks after taking care of COVID-19 patients [27]. However, proven nosocomial infections occurred during loosening of barrier measures between HCWs, [28] lead outbreaks that can reached high attack rates [29]. In March 2020, Belingheri et al. [30], faced with the progression of the epidemic in Italy, with many nosocomial cases, warned of the potential risks for HCWs, especially during moments of contact between colleagues at work, such as meals, breaks, and clinical handoffs. We observed that these types of contact occurred at least once in 74% of the HCW-HCW transmissions that we analyzed. SARS-COV-2 is an “anti-social” virus, which does not allow the relaxation of preventive measures, which can be a source of stress or even depression in caregivers [[31], [32], [33]].

This study has several limitations. First, we concentrated the study on HCWs working in health facilities and did not consider HCWs working in the medico-social sector or in ambulatory care, where identification of cases was more challenging. Second, as the HCW screening policy was not homogeneous in the region, some community cases may not have been identified, and the incidence may be underestimated. However, we believe that the detection of nosocomial cases approached completeness, related to the identification of nosocomial cases by infection prevention and control teams and the existence of the national nosocomial infection reporting system [12]. Third, it is possible that some cases that we considered nosocomial were in fact community-acquired. We made sure to limit this classification bias by carrying out the study in phase II of the epidemic, without active circulation of the virus in the community, and by questioning caregivers directly and systematically about their possible contacts with suspected or confirmed cases of COVID-19.

Our investigation demonstrated that HCWs who were not assigned to the care of COVID-19 patients were not prepared for the arrival of this particularly insidious new virus, which is spreading rapidly from asymptomatic colleagues or patients, or presented only with atypical or nonspecific symptoms. Gradually, from the end of phase II of the epidemic, “universal masking” policies were implemented in all establishments, as well as measures of social distancing during moments of close contact between professionals. At a time when Europe is facing a second wave, and when the vaccine is still in the development phase, our data suggest that “universal masking” and social distancing policies in health care settings must be maintained. However, although wearing a face mask seems effective for prevention for both HCWs and the general public [[34], [35], [36]], universal masking alone is not a panacea [37] and should be accompanied by the basic prevention measures of hand hygiene and the wearing of other PPE (eye protection, gowns, apron, gloves), respecting their indications and uses. Organizational measures are also needed for the admission and care of patients (appropriate triaging, bed allocation, vigilance towards patients triaged in low risk groups, low threshold for testing …). We hope to have made a useful contribution to the reflection on the evolution of these measures.

Author contributions

P. Thibon, S. Le Hello and F. Borgey designed the study. P. Thibon, S. Le Hello and P. Breton applied for the ethics. A. Bidon, F. Haupais, P. Thibon, C. Séguineau, T. Letourneur, P. Gautier, C. Darrigan, E. Périlleux and P. Breton collected data. P. Thibon analyzed data and wrote the manuscript. S. Le Hello, F. Borgey, A. Mouet, M. Le Gouilh and P. Breton revised the manuscript. All authors contributed to data acquisition, data analysis, data interpretation, and reviewed and approved the final version. The corresponding author had full access to all the data in the study and had final responsibility for the decision to submit for publication.

Data access

Thibon P and Le Hello S had full access to all the data in the study and take responsibility for the integrity of the data and the accuracy of the data analysis.

Data sharing statement

The data set analyzed in this paper is available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Acknowledgements

We thank all collaborators:Isabelle Aveline (Clinique, Alençon, France); Aurélie Berthou (Clinique de la Miséricorde, Caen, France); Tifenn Boutard (Polyclinique du Parc, Caen, France); Régis Brunet (Centre de Soins de Suite et Réadaptation L'Adapt Manoir d'Aprigny, Bayeux, France); Anne Canivet (Centre de Coordination de la Lutte contre le Cancer François Baclesse, Caen, France); Valérie Champroux (Etablissement Public de Santé, Bellême, France); Nadine Chesnel (Centre Hospitalier, Carentan, France); Erwan Clech (Polyclique de la Baie, Avranches, France); Jean-Luc Coget (Centre Hospitalier, Sées, France); Christine Delaunay (Centre de Soins de Suite et Réadaptation Le Parc, Bagnoles de l'Orne, France); Isabelle Deschamps (Centre Hospitalier Psychiatrique, Saint-Lô, France); Jérôme Descout (Centre Hospitalier, L'Aigle, France); Perrine Descout (Centre Hospitalier, Vimoutiers, France); Elisabeth Durand (Centre Pychothérapique de l’Orne, Alençon, Orne); Nadège Friedrich (Centre de Soins de Suite et Réadaptation, IFS, France); Sylvie Gilles (Centre Hospitalier, Côte Fleurie, Cricqueboeuf, France); Sylvie Gouerec (Centre de Médecine Physique et Réadaptation La Clairière, Flers, France); Isabelle Herluison-Petit (Centre Hospitalier, Falaise, France); Sandrine Junguene (Polyclinique de la Manche, Saint-Lô, France); Stéphanie Juteau (Centre Hospitalier de l'Estran, Pontorson, France); Sophie Leconte (Clinique Notre Dame, Vire, France); Christine Lepleux (Centre de Médecine Physique et Réadaptation, Bagnoles de l'Orne, France); Pascale Morvan (Institut de Médecine Physique et Réadaptation, Hérouville-Saint-Clair, France); Julie Neuquelman (Polyclinique du Cotentin, Equeurdreville, France); Agnès Palix (Centre de Coordination de la Lutte contre le Cancer François Baclesse, Caen, France); Anne Peskine (Etablissement de Médecine Physique et Réadaptation Le Normandy, Granville, France); Magali Plihon (Etablissement de Médecine Physique et Réadaptation Le Normandy, Granville, France); Laurence Pontier (Centre de Soins de Suite et Réadaptation Korian William Harvey, Saint Martin d'Aubigny, France); Véronique Savary (Clinique Henri Guillard, Coutances, France); Yolène Rousseau (Polyclinique, Deauville, France); Emmanuelle Savigny (Centre de Soins de Suite et Réadaptation Korian Thalatta, Ouistreham, France); Marc Thebault (Centre de Soins de Suite et Réadaptation Korian l'Estran, Siouville, France).All the authors acknowledge Eva Thibon for map creation.

Footnotes

Supplementary data related to this article can be found at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.infpip.2020.100109.

Contributor Information

Simon Le Hello, Email: lehello-s@chu-caen.fr.

the ECRAN Investigation group:

Alexandra Allaire, Valérie Auclair, Sophie Beuve Krug, Guy-Claude Borderan, Corine Chauvin, Sylvie Dargere, Dominique Degallaix, Joël Delhomme, Stéphane Erouart, Alexis Hautemaniere, Paul Ionescu, François-Xavier Le Foulon, Stéphanie Lefflot, Elisabeth Lefol-Seillier, Marie-Line Levallois, Mélanie Martel, Jocelyn Michon, Dominique Olliver, Aurélie Thomas-hervieu, Astrid Vabret, Carole Vaucelle, and Renaud Verdon

Conflict of interest statement

All the authors and contributors declare no conflicts of interest.

Funding source

None.

Appendix ASupplementary data

The following is the supplementary data related to this article:

Multimedia component 1

References

- 1.Zhu N., Zhang D., Wang W., Li X., Yang B., Song J. A novel Coronavirus from patients with pneumonia in China, 2019. N Engl J Med. 2020;382(8):727–733. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa2001017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bernard Stoecklin S., Rolland P., Silue Y., Mailles A., Campese C., Simondon A. First cases of Coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) in France: surveillance, investigations and control measures, January 2020. Euro Surveill. 2020;25(6):2000094. doi: 10.2807/1560-7917.ES.2020.25.6.2000094. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ministère de la Santé et des Solidarités Methodological guide – Covid-19 epidemic phase (16 March 2020 version) https://solidarites-sante.gouv.fr/IMG/pdf/guide-covid-19-phase-epidemique-v15-16032020.pdf

- 4.He X., Lau E.H.Y., Wu P., Deng X., Wang J., Hao X. Temporal dynamics in viral shedding and transmissibility of COVID-19. Nat Med. 2020;26(5):672–675. doi: 10.1038/s41591-020-0869-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Li Q., Guan X., Wu P., Wang X., Zhou L., Tong Y. Early transmission dynamics in Wuhan, China, of novel Coronavirus-infected pneumonia. N Engl J Med. 2020;382(13):1199–1207. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa2001316. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Arons M.M., Hatfield K.M., Reddy S.C., Kimball A., James A., Jacobs J.R. Presymptomatic SARS-CoV-2 infections and transmission in a skilled nursing facility. N Engl J Med. 2020;382(22):2081–2090. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa2008457. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Huang D., Lian X., Song F., Ma H., Lian Z., Liang Y. Clinical features of severe patients infected with 2019 novel coronavirus: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Ann Transl Med. 2020;8(9):576. doi: 10.21037/atm-20-2124. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Cheng H.Y., Jian S.W., Liu D.P., Ng T.C., Huang W.T., Lin H.H. Taiwan COVID-19 Outbreak Investigation Team. Contact tracing assessment of COVID-19 transmission dynamics in taiwan and risk at different exposure periods before and after symptom onset. JAMA Intern Med. 2020 doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2020.2020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Park M., Cook A.R., Lim J.T., Sun Y., Dickens B.L. A systematic review of COVID-19 epidemiology based on current evidence. J Clin Med. 2020;9(4):967. doi: 10.3390/jcm9040967. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Santé Publique France Criteria for defining a risk exposure zone. https://www.santepubliquefrance.fr/media/files/01-maladies-et-traumatismes/maladies-et-infections-respiratoires/infection-a-coronavirus/criteres-d-elargissement-zones-d-exposition-a-risque-covid-19-13-03-20

- 11.Corman V.M., Landt O., Kaiser M., Molenkamp R., Meijer A., Chu D.K. Detection of 2019 novel coronavirus (2019-nCoV) by real-time RT-PCR. Euro Surveill. 2020;25(3):2000045. doi: 10.2807/1560-7917.ES.2020.25.3.2000045. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Santé Publique France E-SIN A new tool for reporting nosocomial infections. https://www.santepubliquefrance.fr/maladies-et-traumatismes/infections-associees-aux-soins-et-resistance-aux-antibiotiques/infections-associees-aux-soins/documents/article/e-sin-un-nouvel-outil-au-service-du-signalement-des-infections-nosocomiales

- 13.Ministère de la Santé et des Solidarités La Statistique annuelle des établissements (SAE) https://drees.solidarites-sante.gouv.fr/etudes-et-statistiques/open-data/etablissements-de-sante-sociaux-et-medico-sociaux/article/la-statistique-annuelle-des-etablissements-sae

- 14.van Doremalen N., Bushmaker T., Morris D.H., Holbrook M.G., Gamble A., Williamson B.N. Aerosol and surface stability of SARS-CoV-2 as compared with SARS-CoV-1. N Engl J Med. 2020;382(16):1564–1567. doi: 10.1056/NEJMc2004973. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Gandhi R.T., Lynch J.B., del Rio C. Mild or moderate Covid-19. N Engl J Med. 2020 doi: 10.1056/nejmcp2009249. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.World Health Organisation Modes of transmission of virus causing COVID-19: implications for IPC precautions recommendations. https://www.who.int/news-room/commentaries/detail/modes-of-transmission-of-virus-causing-covid-19-implications-for-ipc-precaution-recommendations

- 17.Bai Y., Yao L., Wei T., Tian F., Jin D.Y., Chen L. Presumed asymptomatic carrier transmission of COVID-19. JAMA. 2020;323(14):1406–1407. doi: 10.1001/jama.2020.2565. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Zou L., Ruan F., Huang M., Liang L., Huang H., Hong Z. SARS-CoV-2 viral load in upper respiratory specimens of infected patients. N Engl J Med. 2020;382(12):1177–1179. doi: 10.1056/NEJMc2001737. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Gandhi M., Yokoe D.S., Havlir D.V. Asymptomatic transmission, the Achilles' heel of current strategies to control Covid-19. N Engl J Med. 2020;382(22):2158–2160. doi: 10.1056/NEJMe2009758. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Nishiura H., Linton N.M., Akhmetzhanov A.R. Serial interval of novel coronavirus (COVID-19) infections. Int J Infect Dis. 2020;93:284–286. doi: 10.1016/j.ijid.2020.02.060. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Du Z., Xu X., Wu Y., Wang L., Cowling B.J., Meyers L.A. Serial interval of COVID-19 among publicly reported confirmed cases. Emerg Infect Dis. 2020;26(6):1341–1343. doi: 10.3201/eid2606.200357. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Zhang J., Litvinova M., Wang W., Wang Y., Deng X., Chen X. Evolving epidemiology and transmission dynamics of coronavirus disease 2019 outside Hubei province, China: a descriptive and modelling study. Lancet Infect Dis. 2020;20(7):793–802. doi: 10.1016/S1473-3099(20)30230-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Wu Z., McGoogan J.M. Characteristics of and important lessons from the coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) outbreak in China: summary of a report of 72314 cases from the Chinese center for disease control and prevention. JAMA. 2020;323(13):1239. doi: 10.1001/jama.2020.2648. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Lai X., Wang M., Qin C., Tan L., Ran L., Chen D. Coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-2019) infection among health care workers and implications for prevention measures in a tertiary hospital in Wuhan, China. JAMA Netw Open. 2020;3(5) doi: 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2020.9666. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Hunter E., Price D.A., Murphy E., van der Loeff I.S., Baker K.F., Lendrem D. First experience of COVID-19 screening of health-care workers in England. Lancet. 2020;395(10234):e77–e78. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(20)30970-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kluytmans-van den Bergh M.F.Q., Buiting A.G.M., Pas S.D., Bentvelsen R.G., van den Bijllaardt W., van Oudheusden A.J.G. Prevalence and clinical presentation of health care workers with symptoms of coronavirus disease 2019 in 2 Dutch hospitals during an early phase of the pandemic. JAMA Netw Open. 2020;3(5) doi: 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2020.9673. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Hibino M., Iwabuchi S., Munakata H. SARS-CoV-2 IgG seroprevalence among medical staff in a general hospital that treated covid-19 patients in japan: retrospective evaluation of nosocomial infection control. J Hosp Infect. 2020 Oct 8;S0195–6701(20):30461–30468. doi: 10.1016/j.jhin.2020.10.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Lucey M., Macori G., Mullane N., Sutton-Fitzpatrick U., Gonzalez G., Coughlan S. Whole-genome sequencing to track SARS-CoV-2 transmission in nosocomial outbreaks. Clin Infect Dis. 2020 Sep 19 doi: 10.1093/cid/ciaa1433. ciaa1433. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Correa-Martínez C.L., Schwierzeck V., Mellmann A., Hennies M., Kampmeier S. Healthcare-Associated SARS-CoV-2 Transmission-Experiences from a German University Hospital. Microorganisms. 2020 Sep 8;8(9):1378. doi: 10.3390/microorganisms8091378. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Belingheri M., Paladino M.E., Riva M.A. Beyond the assistance: additional exposure situations to COVID-19 for healthcare workers. J Hosp Infect. 2020;105(2):353. doi: 10.1016/j.jhin.2020.03.033. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Lai J., Ma S., Wang Y., Cai Z., Hu J., Wei N. Factors associated with mental health outcomes among health care workers exposed to coronavirus disease 2019. JAMA Netw Open. 2020;3(3) doi: 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2020.3976. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Yin Q., Sun Z., Liu T., Ni X., Deng X., Jia Y. Posttraumatic stress symptoms of health care workers during the corona virus disease 2019. Clin Psychol Psychother. 2020;27(3):384–395. doi: 10.1002/cpp.2477. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Chou R., Dana T., Buckley D.I., Selph S., Fu R., Totten A.M. Epidemiology of and risk factors for coronavirus infection in health care workers. Ann Intern Med. 2020:M20–M1632. doi: 10.7326/M20-1632. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Chu D.K., Akl E.A., Duda S., Solo K., Yaacoub S., Schunemann H.J. Physical distancing, face masks, and eye protection to prevent person-to-person transmission of SARS-CoV-2 and COVID-19: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Lancet. 2020;395(10242):1973–1987. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(20)31142-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Bartoszko J.J., Farooqi M.A.M., Alhazzani W., Loeb M. Medical masks vs N95 respirators for preventing COVID-19 in healthcare workers: A systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized trials. Influenza Other Respir Viruses. 2020;14(4):365–373. doi: 10.1111/irv.12745. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Wang X., Ferro E.G., Zhou G., Hashimoto D., Bhatt D.L. Association Between Universal Masking in a Health Care System and SARS-CoV-2 Positivity Among Health Care Workers. JAMA. 2020 Jul 14 doi: 10.1001/jama.2020.12897. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Klompas M., Morris C.A., Sinclair J., Pearson M., Shenoy E.S. Universal masking in hospitals in the Covid-19 era. N Engl J Med. 2020;382(21):e63. doi: 10.1056/NEJMp2006372. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Multimedia component 1