Abstract

Background and aim

The novel coronavirus disease (COVID-19) caused by severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2) is now become a worldwide pandemic bringing over 71 million confirmed cases, while the specific drugs and vaccines approved for this disease are still limited regarding their effectiveness and adverse events. Since virus incidences are still on rise, infectivity and mortality may also rise in the near future, natural products are highly considered to be valuable sources for the discovery of new antiviral drugs against SARS-CoV-2. This present review aims to comprehensively summarize the up-to-date scientific literatures on biological activities of plant- and mushroom-derived compounds relevant to mechanistic targets involved in SARS-CoV-2 infection and inflammatory-associated pathogenesis, including viral entry, replication and release, and the renin-angiotensin-aldosterone system (RAAS).

Experimental procedure

Data were retrieved from a literature search available on PubMed, Scopus and Google Scholar databases and collected until the end of May 2020. The findings from in vitro cell and non-cell based studies were considered, while the results of in silico studies were excluded.

Results and conclusion

Based on the previous findings in SARS-CoV studies, except in silico molecular docking analysis, herein, we provide a total of 150 natural compounds as potential candidates for development of new anti-COVID-19 drugs with higher efficacy and lower toxicity than the existing therapeutic agents. Several natural compounds have showed their promising actions on multiple therapeutic targets, which should be further explored. Among them, quercetin, one of the most abundant of plant flavonoids, is proposed as a lead candidate with its ability on the virus side to inhibit SARS-CoV spike protein-angiotensin-converting enzyme 2 (ACE2) interaction, viral protease and helicase activities, as well as on the host cell side to inhibit ACE activity and increase intracellular zinc level.

Keywords: SARS-CoV-2, 2019-nCoV, Anti-viral, Therapeutic strategies, Natural compound, Herbal medicine, Plant, Mushroom

Graphical abstract

Highlights of the findings and novelties

-

•

Relevant and up-to-date publications in natural products with anti-COVID-19 potential.

-

•

Emphasis on the potential of anti-COVID-19 plant/mushroom-based medicine.

-

•

Twenty four proposed natural compounds for the anti-COVID-19 drug candidates.

-

•

Quercetin emerged as the most promising compound acting on multiple therapeutic targets.

List of abbreviations

- 3CLpro

3-chymotrypsin-like main protease

- ACE

Angiotensin-converting enzyme

- ARB

Angiotensin-receptor blocker

- ARDS

Acute respiratory distress syndrome

- AT1R

Angiotensin II type 1 receptor

- COVID-19

Coronavirus Disease 2019

- MERS-CoV

Middle East Respiratory Syndrome Coronavirus

- Nsp

Non-structural protein

- PLpro

Papain-like protease

- RAAS

Renin–angiotensin–aldosterone system

- RdRp

RNA-dependent RNA polymerase

- RTC

Replication-transcription complex

- SARS-CoV

Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome Coronavirus

- SARS-CoV-2

Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome Coronavirus 2

- TMPRSS2

Transmembrane protease serine 2

- V-ATPase

Vacuolar-type H+-ATPase

1. Introduction

On 31 December 2019, several cases of pneumonia were reported in Wuhan, the epicenter of the outbreak in Hubei province of China.1 The novel coronavirus was identified as Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome Coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2) which causes Coronavirus Disease 2019 (COVID-19) pandemic.2,3 From the time of emergence until present, COVID-19 has spread worldwide in which a total of over 71 million confirmed cases with over 1.6 million death tolls has been reported by the World Health Organization (WHO). The COVID-19 positive cases continue rising and is widely distributed throughout the world with the prevalence ranging from highest in America, followed by Europe and South-East Asia, and lowest in Western Pacific region. Asymptomatic patients and patients with mild symptoms can be recovered under home care and isolation while patients with severe complications including acute respiratory distress syndrome (ARDS) require intensive care unit (ICU) which involves oxygen therapy.4,5 Currently, there is scant evidence from clinical trials for WHO to approve any standard drugs or vaccines as several trials have failed due to efficacy and safety concerns.6,7 Natural compounds from plant and fungi sources have been recognized in their antiviral properties with numerous mechanisms to prevent infection and strengthen host immunity.8,9 Herein, we reviewed potential antiviral compounds with multiple targets of action relating to coronaviruses including inhibiting of viral entry, replication and release, and compounds targeting renin–angiotensin–aldosterone system (RAAS) which exhibit promising effects against the disease. We also proposed future perspectives in adopting natural compounds to combat against the COVID-19.

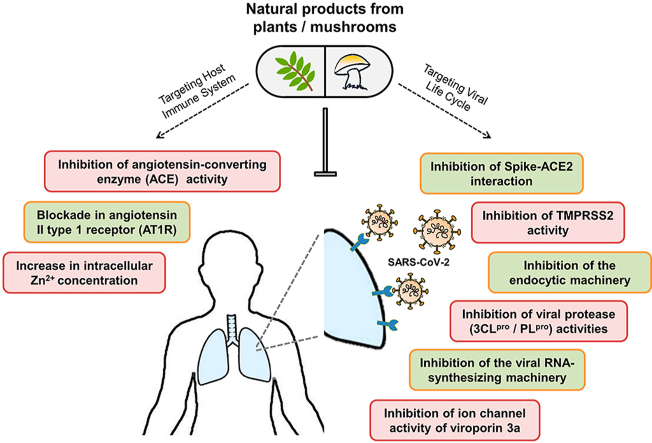

2. Promising therapeutic strategies for the treatment of COVID-19 infection

Presently, there is no clinically approved therapeutics for treating COVID-19, while the rapid human-to-human transmission of this viral infection has expanded worldwide. As the efficacy and safety of natural products on the treatment of a number of viruses including SARS-CoV and Middle East Respiratory Syndrome Coronavirus (MERS-CoV), have been widely acknowledged for several years,10 the compounds derived from natural sources, e.g. plants and fungi, could have the potential to be a powerful anti-COVID-19 drug. In this review, we focused on four main categories of therapeutic strategies that aim to target the cellular machinery at each step of virus life cycle, starting from viral entry and replication to the release of viral progenies, as well as the RAAS which is a main target of the treatment of hypertension and has recently been proposed as another promising alternative in the treatment of COVID-19. The multiple potential therapeutic mechanisms, both specific and general, that could be capable of tackling COVID-19 infection are presented in Fig. 1.

Fig. 1.

Schematic illustration of potential therapeutic mechanisms in COVID-19 infection. The potential therapeutic strategies for SARS-CoV-2 infection proposed here fall into four main categories based on the cellular and molecular machinery required for the viral life cycle and its related pathogenic mechanisms: inhibition of virus entry, inhibition of virus replication, blocking the release of viral progenies, and modifying the RAAS. The selective blockade of the S protein-ACE2 binding (❶), TMPRSS2 activity (❷), and endocytic pathway-associated proteins such as clathrin, the vacuolar-type H+-ATPase (V-ATPase), and cathepsin L (❸), prevent the internalization of virus within the cell. Virus multiplication can be blocked through direct inhibition of proteolytic activity of two viral proteases, 3CLpro and PLpro (❹), and replicative activity of viral RTC components e.g., RdRp and helicase (❺), or indirect enzyme inhibition by increasing intracellular Zn2+ concentration (❻). Silencing the expression and ion channel activity of viroporin 3a suppresses the release of viral particles from infected cells (❼). Overactivation of Ang II/AT1R axis which contributes to excessive inflammation, can be suppressed by blockade of ACE (❽) and AT1R (❾). 3CLpro, 3-chymotrypsin-like protease; ACE2, angiotensin-converting enzyme 2; Ang, angiotensin; AT1R, angiotensin II type 1 receptor; E, envelope; MasR, mitochondrial assembly receptor; M, membrane; N, nucleocapsid; PLpro, papain-like protease; pp, polyprotein; RAAS, renin-angiotensin-aldosterone system; RdRp, RNA-dependent RNA polymerase; RTC, replication-transcription complex; S, spike; TMPRSS2, transmembrane protease serine 2.

The first therapeutic strategy targets on the mechanisms of virus entry in which the selective blockade of molecules that facilitates the internalization of virus into the host cells could be effective to prevent infection. Upon the binding of a virus surface spike (S) protein to a cellular receptor angiotensin-converting enzyme 2 (ACE2), the SARS-CoV-2 generally enters into target host cells via two primary routes; viral membrane fusion and the more common endocytic uptake.11 The first entry mechanism is assisted by proteolytic activation of S protein by a host cell transmembrane protease serine 2 (TMPRSS2), which allows not only direct fusion of virus at the plasma membrane surface, but also release of viral genomic RNA into the cytoplasm. On the other hand, without the membrane bound protease TMPRSS2, the latter entry mechanism allows the whole viral particle to be uptaken via receptor-mediated endocytosis, before subsequently uncoated following the S protein cleavage by cathepsin L within the endosome, to unveil its RNA genome into the cell.

The second and third therapeutic strategies focus on the inhibition of progeny virus production and release from infected cells. As far as the viral replication process is concerned,12 it begins with the translation of released genome of SARS-CoV-2, a single-stranded (positive-sense) RNA of approximately 30 kb in length, into two precursor polyproteins, pp1a and pp1ab. Both are further cleaved by virus-encoded proteases into several non-structural proteins (nsps) including two key replicative enzymes: the nsp12-RNA-dependent RNA polymerase (RdRp) and the nsp13-helicase, to form the replication-transcription complex (RTC) for synthesizing a full-length genomic RNA (replication) or a nested set of subgenomic mRNA (transcription). These mRNAs are translated into all relevant structural proteins, which together with the viral genome are subsequently assembled into new virions and finally released outside the cell through viroporin-mediated viral budding.13

The last therapeutic strategy involves modulating the immune system with the RAAS which regulates blood pressure, fibrosis, and inflammation. In this system, angiotensin-converting enzyme (ACE) converts angiotensin I to angiotensin II which is then converted to lung-protective angiotensin-(1–7) by ACE2. The angiotensin-(1–7) is further recognized by its receptor, the G-protein coupled receptor Mas, to reduce blood pressure, fibrosis, and inflammation.14 However, as SARS-CoV-2 enters the cells by binding to ACE2, the normal functions of ACE2 are then suppressed. Therefore, instead of converting to angiotensin-(1–7), the angiotensin II is largely bound to type 1 angiotensin II type 1 receptor (AT1R) which causing increased inflammation and other deleterious effects, particularly in the renal and cardiovascular systems.15

3. Potential natural products as drug candidates against COVID-19

The data presented in this review were obtained from PubMed, Scopus and Google Scholar database up to May 2020. The terms of natural compound, natural product, plant and mushroom were individually searched along with the terms corresponding to each target molecule. Here, we summarize plant- and mushroom-derived compounds that have been reported of antiviral activity with known therapeutic mechanisms specifically against SARS-CoV infection, performed by in vitro cell or non-cell based experiments but not in silico method, as potential candidates to be further researched. We also propose certain promising natural compounds targeting general mechanisms involved in coronavirus infection (see Fig. 1). Additionally, the reports on natural compounds against SARS-CoV with unidentified mechanism of action were included in this review.

3.1. Natural bioactive compounds targeting viral entry

3.1.1. The S protein-ACE2 interaction

The S protein plays a pivotal role in the entry of coronaviruses into host cells by recognizing and binding to the ACE2 via multivalent bonds.16 The attachment of S protein to ACE2 receptor leads to the fusion between the viral envelope and host cell membrane resulting in successful transfer of viral genome into infected cells.17,18 S protein is composed of two functional subunits, S1 and S2. The S1 is responsible for binding to the host cell receptor through the receptor binding domain (RDB), while the S2 causes fusion of the viral and cellular membranes.19,20 Sequence alignment results showed that the homology of the S protein RBD sequence between the beta coronaviruses SARS-CoV and SARS-CoV-2 is 76%.21 A number of evidence revealed human ACE2 (hACE2) molecule as an entry receptor for both SARS-CoV and SARS-CoV-2 S proteins.22, 23, 24, 25 Notably, S protein of SARS-CoV-2 was found to exhibit greater affinity to the ACE2 receptor than that of SARS-CoV.24 In addition, expression of ACE2 is ubiquitous with diverse functions, however its specific functions are demonstrated in several organs including lung, tongue, heart, kidney, gastrointestinal tract, pancreas and brain.26,27 Accordingly, multiple symptoms could be observed in COVID-19 patients.27 Several observations have been reported that the use of hydroxychloroquine, an ACE2 FDA-approved antagonist, was able to reduce mortality rate in hospitalized COVID-19 patients.28 Therefore, it is apparent that the S protein-hACE2 interaction complex is the most crucial target for searching appropriate inhibitors to inhibit entry of the virus in the host cell.

Several natural compounds have been demonstrated their activity to inhibit SARS-CoV entry to the host cell as shown in Table 1. According to the literature, an anthraquinone compound, emodin, showed the potency to inhibit viral infection by blocking the binding of SARS-CoV S protein to ACE2 in a dose-dependent manner.29 The plant sources which are likely to contain emodin as their active constituent were also found effective in blocking SARS-CoV S protein and ACE2 interaction, with showing IC50 values for aqueous extracts from the root of Rheum palmatum, the root and stem of Polygonum multiflorum, ranged from 1 to 10 μg/ml.29 Another previous study using the high-throughput screening technique revealed more promising natural antiviral compounds consisted in the extracts from Chinese herbs. Those small herbal molecules could strongly bind to the SARS-CoV S2 protein and inhibited the pseudovirus entry, possibly by interfering with the function of the S protein.30

Table 1.

List of bioactive compounds from natural sources as potential anti-COVID-19 drug candidates and their mechanisms of action.

| Compound | Class | Source | Biological action/Efficacy | Experiment | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Inhibiting the SARS-CoV S protein-ACE2 interaction | |||||

| Emodin | Anthraquinone | Rheum palmatuma | IC50 = 200 μM | Cell-free assay (Competitive biotinylated ELISA) | 29 |

| 94% inhibition at EC of 50 μM | Cell-based assay (IFA) | ||||

| Luteolin | Flavonoid | Rhodiola kirilowiia | IC50 = 4.5 μM | Cell-free and cell-based assay (FAC/MS and Luciferase assay) | 30 |

| Quercetin | Flavonoid | Allium cepaa | IC50 = 83.4 μM | Cell-based assay (Luciferase assay) | 30 |

| Tetra-O-galloyl--d-glucose (TGG) | Tannin | Galla chinensisa | IC50 = 10.6 μM | Cell-free and cell-based assay (FAC/MS and Luciferase assay) | 30 |

| Inhibiting the endocytic machinery | |||||

| 1-cinnamoyl-3,11-dihydroxy meliacarpin | Terpenoid | Melia azedarach | increased endolysosomal pH (EC of 7.5 μM) | Cell-based assay (AO staining) | 38 |

| 25-O-acetyl-7,8-didehydrocimigenol 3-O-beta-d-xylopyranoside (ADCX) | Terpenoid | Cimicifugae rhizoma | inhibited degradation activity by decreasing cathepsin expression, but not endolysosomal acidity (EC of 24 μM) | Cell-based assay (AO staining, DQ-BSA staining and WB) | 39 |

| Alantolactone | Sesquiterpene lactone | Inula heleniuma | neutralized endo-lysosomal pH and reducing the expression and activity of cathepsins (EC of 10 μM) | Cell-based assay (LysoTracker Red and AO staining, WB and Cathepsin activity assay) | 76 |

| Cleistanthin A | Lignan glycoside | Cleistanthus collinua | inhibited the activity of V-type ATPase and elevated endolysosomal pH (EC of 0.1 μM) | Cell-based assay (pH sensitive fluorescent probe/LysoTracker Red staining and V-type ATPase activity assay) | 77,78 |

| Cleistanthoside A tetraacetate | Lignan glycoside | Phyllanthus taxodiifolius Beille a | neutralized endolysosomal acidity and decreased the activity of V-type ATPase (EC of 50 nM) | Cell-based assay (LysoTracker Red staining and V-type ATPase activity assay) | 78 |

| Dauricine | Alkaloid | Rhizoma Menispermia | elevated endolysosomal pH, decreased the levels of active cathepsins and inhibited the activity of V-type ATPase (EC of 10 μM) | Cell-based assay (LysoSensor Yellow/Blue staining, WB and V-type ATPase activity assay) | 42 |

| Daurisoline | Alkaloid | Rhizoma Menispermia | elevated endolysosomal pH, decreased the levels of active cathepsins and inhibited the activity of V-type ATPase (EC of 10 μM) | Cell-based assay (LysoSensor Yellow/Blue staining, WB and V-type ATPase activity assay) | 42 |

| Diphyllin | Lignan lactone | Cleistanthus collinusa | inhibited the activity of V-type ATPase (EC of 0.3 μM) | Cell-based assay (V-type ATPase activity assay) | 79 |

| Ginsenoside Ro | Triterpenoid saponin | Panax ginseng | raised endolysosomal pH and downregulating the expression and activity of cathepsins (EC of 50 μM) | Cell-based assay (AO staining, WB and Cathepsin activity assay) | 80 |

| Icariside II | Flavonoid | Epimedium koreanum Nakai | decreased endolysosomal acidity (EC of 25 μM) | Cell-based assay (AO staining) | 81 |

| Leelamine | Terpene | Pinus sylvestrisa | decreased endolysosomal acidity and inhibited cellular endocytosis (EC of 3 μM) | Cell-based assay (LysoTracker Red staining and Internalization of fluorescent transferrin-A488) | 40 |

| Matrine | Alkaloid | Sophora flavescens Ait | inhibited endolysosomal acidification and reduced the expression and activity of cathepsins (EC of 2 mM) | Cell-based assay (LysoSensor Yellow/Blue, WB and Cathepsin activity assay) | 43 |

| Myrtenal | Terpene | Elettaria cardamomuma | inhibited the activity of V-type ATPase and reduced endolysosomal acidification (EC of 100 μM) | Cell-based assay (AO staining and V-type ATPase activity assay) | 41 |

| Oblongifolin C | Benzophenone | Garcinia yunnanensis Hu | inhibited endolysosomal acidification and downregulated the expression and activity of cathepsins (EC of 15 μM) | Cell-based assay (AO staining, WB and Cathepsin activity assay) | 82 |

| Pulsatilla saponin D | Triterpenoid saponin | Pulsatilla chinensis (Bunge) Regel | elevated endolysosomal pH and downregulated cathepsins (EC of 1.25 μM) |

Cell-based assay (LysoSensor Yellow/Blue, WB and Cathepsin activity assay) | 83 |

| Tetrandrine | Alkaloid | Stephania tetrandra S. Moore a | elevated endolysosomal pH in a concentration-dependent manner (EC of 1–10 μM) | Cell-based assay (LysoSensor Yellow/Blue staining) | 44 |

| Inhibiting the SARS-CoV 3CLproactivity | |||||

| 3’-(3-Methylbut-2-enyl)-3′,4,7-trihydroxyflavane | Flavonoid | Broussonetia papyrifera | IC50 = 30.2 μM | Cell-free assay (FRET) | 84 |

| 4-Hydroxyderricin | Chalcone | Angelica keiskei | IC50 = 81.4 μM | Cell-free assay (FRET) | 35 |

| IC50 = 50.8 μM | Cell-based assay (Luciferase reporter assay) | ||||

| Betulinic acid | Terpenoid | Breynia fruticosea | IC50 = 10 μM | Cell-free assay (FRET) | 49,50 |

| Broussochalcone A | Chalcone | Broussonetia papyrifera | IC50 = 88.1 μM | Cell-free assay (FRET) | 84 |

| Broussochalcone B | Chalcone | Broussonetia papyrifera | IC50 = 57.8 μM | Cell-free assay (FRET) | 84 |

| Broussoflavan A | Flavonoid | Broussonetia papyrifera | IC50 = 92.4 μM | Cell-free assay (FRET) | 84 |

| Dihydrotanshinone I | Tanshinone | Salvia miltiorrhiza | IC50 = 14.4 μM | Cell-free assay (FRET) | 51 |

| Hesperetin | Flavonoid | Isatis indigotica | IC50 = 60 μM | Cell-free assay (ELISA) | 48 |

| IC50 = 8.3 μM | Cell-based assay (Luciferase reporter assay) | ||||

| Hirsutenone | Diarylheptanoid | Alnus japonica | IC50 = 36.2 μM | Cell-free assay (FRET) | 85 |

| Isobavachalcone | Chalcone | Angelica keiskei | IC50 = 39.4 μM | Cell-free assay (FRET) | 35 |

| IC50 = 11.9 μM | Cell-based assay (Luciferase reporter assay) | ||||

| Isoliquiritigenin | Chalcone | Glycyrrhiza glabraa | IC50 = 61.9 μM | Cell-free assay (FRET) | 84,86 |

| Kazinol A | Flavonoid | Broussonetia papyrifera | IC50 = 84.8 μM | Cell-free assay (FRET) | 84 |

| Kazinol F | Biphenyl propanoids | Broussonetia papyrifera | IC50 = 43.3 μM | Cell-free assay (FRET) | 84 |

| Kazinol J | Biphenyl propanoids | Broussonetia papyrifera | IC50 = 64.2 μM | Cell-free assay (FRET) | 84 |

| Methyl tanshinonate | Tanshinone | Salvia miltiorrhiza | IC50 = 21.1 μM | Cell-free assay (FRET) | 51 |

| Quercetin | Flavonoid | Allium cepaa | IC50 = 52.7 μM | Cell-free assay (FRET) | 84,87 |

| Quercetin-3-b-galactoside | Flavonoid | Machilus zuihoensisa | IC50 = 42.8 μM | Cell-free assay (FRET) | 87,88 |

| Rosmariquinone | Tanshinone | Salvia miltiorrhiza | IC50 = 21.1 μM | Cell-free assay (FRET) | 51 |

| Savinin | Lignoid | Chamaecyparis obtuse var. formosana | IC50 = 25 μM | Cell-free assay (FRET) | 49 |

| Tanshinone I | Tanshinone | Salvia miltiorrhiza | IC50 = 38.7 μM | Cell-free assay (FRET) | 51 |

| Tanshinone IIA | Tanshinone | Salvia miltiorrhiza | IC50 = 89.1 μM | Cell-free assay (FRET) | 51 |

| Tanshinone IIB | Tanshinone | Salvia miltiorrhiza | IC50 = 24.8 μM | Cell-free assay (FRET) | 51 |

| Xanthoangelol | Chalcone | Angelica keiskei | IC50 = 38.4 μM | Cell-free assay (FRET) | 35 |

| IC50 = 5.8 μM | Cell-based assay (Luciferase reporter assay) | ||||

| Xanthoangelol B | Chalcone | Angelica keiskei | IC50 = 22.2 μM | Cell-free assay (FRET) | 35 |

| IC50 = 8.6 μM | Cell-based assay (Luciferase reporter assay) | ||||

| Xanthoangelol D | Chalcone | Angelica keiskei | IC50 = 26.6 μM | Cell-free assay (FRET) | 35 |

| IC50 = 9.3 μM | Cell-based assay (Luciferase reporter assay) | ||||

| Xanthoangelol E | Chalcone | Angelica keiskei | IC50 = 11.4 μM | Cell-free assay (FRET) | 35 |

| IC50 = 7.1 μM | Cell-based assay (Luciferase reporter assay) | ||||

| Xanthoangelol F | Chalcone | Angelica keiskei | IC50 = 34.1 μM | Cell-free assay (FRET) | 35 |

| IC50 = 32.6 μM | Cell-based assay (Luciferase reporter assay) | ||||

| Xanthokeistal A | Chalcone | Angelica keiskei | IC50 = 44.1 μM | Cell-free assay (FRET) | 35 |

| IC50 = 9.8 μM | Cell-based assay (Luciferase reporter assay) | ||||

| Inhibiting the SARS-CoV PLproactivity | |||||

| 3′-O-Methyldiplacol | Flavonoid | Paulownia tomentosa | IC50 = 9.5 μM | Cell-free assay (Fluorescence-based deubiquitination) | 89 |

| 3′-O-Methyldiplacone | Flavonoid | Paulownia tomentosa | IC50 = 13.2 μM | Cell-free assay (Fluorescence-based deubiquitination) | 89 |

| 4′-O-Methylbavachalcone | Chalcone | Psoralea corylifolia | IC50 = 10.1 μM | Cell-free assay (Fluorescence-based deubiquitination) | 90 |

| 4′-O-Methyldiplacol | Flavonoid | Paulownia tomentosa | IC50 = 9.2 μM | Cell-free assay (Fluorescence-based deubiquitination) | 89 |

| 4′-O-Methyldiplacone | Flavonoid | Paulownia tomentosa | IC50 = 12.7 μM | Cell-free assay (Fluorescence-based deubiquitination) | 89 |

| 6-Geranyl-4′,5,7-trihydroxy-3′,5′-dimethoxyflavanone | Flavonoid | Paulownia tomentosa | IC50 = 13.9 μM | Cell-free assay (Fluorescence-based deubiquitination) | 89 |

| Broussochalcone A | Chalcone | Broussonetia papyrifera | IC50 = 9.2 μM | Cell-free assay (Fluorescence-based deubiquitination) | 84 |

| Broussochalcone B | Chalcone | Broussonetia papyrifera | IC50 = 11.6 μM | Cell-free assay (Fluorescence-based deubiquitination) | 84 |

| Cryptotanshinone | Tanshinone | Salvia miltiorrhiza | IC50 = 0.8 μM | Cell-free assay (Fluorescence-based deubiquitination) | 51 |

| Curcumin | Polyphenol | Curcuma longaa | IC50 = 5.7 μM | Cell-free assay (Fluorescence-based deubiquitination) | 85,91 |

| Dihydrotanshinone I | Tanshinone | Salvia miltiorrhiza | IC50 = 4.9 μM | Cell-free assay (Fluorescence-based deubiquitination) | 51 |

| Diplacone | Flavonoid | Paulownia tomentosa | IC50 = 10.4 μM | Cell-free assay (Fluorescence-based deubiquitination) | 89 |

| Hirsutanonol | Diarylheptanoid | Alnus japonica | IC50 = 7.8 μM | Cell-free assay (Fluorescence-based deubiquitination) | 85 |

| Hirsutenone | Diarylheptanoid | Alnus japonica | IC50 = 4.1 μM | Cell-free assay (Fluorescence-based deubiquitination) | 85 |

| Isobavachalcone | Chalcone | Psoralea corylifolia | IC50 = 7.3 μM | Cell-free assay (Fluorescence-based deubiquitination) | 90 |

| Angelica keiskei | IC50 = 13.0 μM | Cell-free assay (Fluorescence-based deubiquitination) | 35 | ||

| Isoliquiritigenin | Chalcone | Glycyrrhiza glabraa | IC50 = 24.6 μM | Cell-free assay (Fluorescence-based deubiquitination) | 84,86 |

| Kaempferol | Flavonoid | Zingiber officinalea | IC50 = 16.3 μM | Cell-free assay (Fluorescence-based deubiquitination) | 84,92 |

| Kazinol J | Biphenyl propanoids | Broussonetia papyrifera | IC50 = 15.2 μM | Cell-free assay (Fluorescence-based deubiquitination) | 84 |

| Methyl tanshinonate | Tanshinone | Salvia miltiorrhiza | IC50 = 9.2 μM | Cell-free assay (Fluorescence-based deubiquitination) | 51 |

| Mimulone | Flavonoid | Paulownia tomentosa | IC50 = 14.4 μM | Cell-free assay (Fluorescence-based deubiquitination) | 89 |

| Neobavaisoflavone | Flavonoid | Psoralea corylifolia | IC50 = 18.3 μM | Cell-free assay (Fluorescence-based deubiquitination) | 90 |

| Papyriflavonol A | Favonoid | Broussonetia papyrifera | IC50 = 3.7 μM | Cell-free assay (Fluorescence-based deubiquitination) | 84 |

| Psoralidin | Flavonoid | Psoralea corylifolia | IC50 = 4.2 μM | Cell-free assay (Fluorescence-based deubiquitination) | 90 |

| Quercetin | Flavonoid | Allium cepaa | IC50 = 8.6 μM | Cell-free assay (Fluorescence-based deubiquitination) | 84,87 |

| Rubranol | Diarylheptanoid | Alnus japonica | IC50 = 12.3 μM | Cell-free assay (Fluorescence-based deubiquitination) | 85 |

| Rubranoside A | Diarylheptanoid | Alnus japonica | IC50 = 9.1 μM | Cell-free assay (Fluorescence-based deubiquitination) | 85 |

| Rubranoside B | Diarylheptanoid | Alnus japonica | IC50 = 8.0 μM | Cell-free assay (Fluorescence-based deubiquitination) | 85 |

| Tanshinone I | Tanshinone | Salvia miltiorrhiza | IC50 = 8.8 μM | Cell-free assay (Fluorescence-based deubiquitination) | 51 |

| Tanshinone IIA | Tanshinone | Salvia miltiorrhiza | IC50 = 1.6 μM | Cell-free assay (Fluorescence-based deubiquitination) | 51 |

| Tanshinone IIB | Tanshinone | Salvia miltiorrhiza | IC50 = 10.7 μM | Cell-free assay (Fluorescence-based deubiquitination) | 51 |

| Terrestrimine | Cinnamic amide | Tribulus terrestris | IC50 = 15.8 μM | Cell-free assay (Fluorescence-based deubiquitination) | 93 |

| Tomentin A | Flavonoid | Paulownia tomentosa | IC50 = 6.2 μM | Cell-free assay (Fluorescence-based deubiquitination) | 89 |

| Tomentin B | Flavonoid | Paulownia tomentosa | IC50 = 6.1 μM | Cell-free assay (Fluorescence-based deubiquitination) | 89 |

| Tomentin C | Flavonoid | Paulownia tomentosa | IC50 = 11.6 μM | Cell-free assay (Fluorescence-based deubiquitination) | 89 |

| Tomentin D | Flavonoid | Paulownia tomentosa | IC50 = 12.5 μM | Cell-free assay (Fluorescence-based deubiquitination) | 89 |

| Tomentin E | Flavonoid | Paulownia tomentosa | IC50 = 5.0 μM | Cell-free assay (Fluorescence-based deubiquitination) | 89 |

| Xanthoangelol | Chalcone | Angelica keiskei | IC50 = 11.7 μM | Cell-free assay (Fluorescence-based deubiquitination) | 35 |

| Xanthoangelol B | Chalcone | Angelica keiskei | IC50 = 11.7 μM | Cell-free assay (Fluorescence-based deubiquitination) | 35 |

| Xanthoangelol D | Chalcone | Angelica keiskei | IC50 = 19.3 μM | Cell-free assay (Fluorescence-based deubiquitination) | 35 |

| Xanthoangelol E | Chalcone | Angelica keiskei | IC50 = 1.2 μM | Cell-free assay (Fluorescence-based deubiquitination) | 35 |

| Xanthoangelol F | Chalcone | Angelica keiskei | IC50 = 5.6 μM | Cell-free assay (Fluorescence-based deubiquitination) | 35 |

| Inhibiting the SARS-CoV helicase activity | |||||

| Myricetin | Flavonoid | Camellia sinensisa | inhibited ATPase activity of SARS-CoV helicase with IC50 of 2.71 μM | Cell-free assay (Colorimetry-based ATP hydrolysis assay) | 94 |

| Quercetin | Flavonoid | Allium cepaa | inhibited duplex DNA-unwinding activity of SARS-CoV NTPase/helicase with IC50 of 8.1 μM | Cell-free assay (FRET-based dsDNA unwinding assay) | 95 |

| Scutellarein | Flavonoid glycoside | Scutellaria baicalensis | inhibited ATPase activity of SARS-CoV helicase with IC50 of 0.86 μM | Cell-free assay (Colorimetry-based ATP hydrolysis assay) | 94 |

| Increasing intracellular Zn2+ | |||||

| Caffeic acid | Phenolic acid | Ocimum basilicuma | increased intracellular Zn2+ level (3-fold increase at EC of 50 μM) | Cell-free assay (using liposome model) | 60 |

| Catechin | Flavonoid | Camellia sinensisa | increased intracellular Zn2+ level (2-fold increase at EC of 50 μM) | Cell-free assay (using liposome model) | 60 |

| Catechol | Phenol | Allium cepaa | increased intracellular Zn2+ level (2-fold increase at EC of 50 μM) | Cell-free assay (using liposome model) | 60 |

| Epigallocatechin-3-gallate (EGCG) | Flavonoid | Camellia sinensisa | increased intracellular Zn2+ level (36-fold increase at EC of 50 μM) | Cell-free assay (using liposome model) | 60 |

| increased the uptake of Zn2+ in both cell (4-fold increase at EC of 100 μM) and liposome model (16-fold increase at EC of 10 μM) | Cell-based assay (Fluorescent Zn2+ indicator) and cell-free assay (using liposome model) | 62 | |||

| Gallic acid | Phenolic acid | Syzygium aromaticuma | increased intracellular Zn2+ level (8-fold increase at EC of 50 μM) | Cell-free assay (using liposome model) | 60 |

| Genistein | Flavonoid | Glycine maxa | increased intracellular Zn2+ level (2-fold increase at EC of 50 μM) | Cell-free assay (using liposome model) | 60 |

| Luteolin | Flavonoid | Rhodiola kirilowiia | increased intracellular Zn2+ level (12-fold increase at EC of 50 μM) | Cell-free assay (using liposome model) | 60 |

| Pyrithione | Organic sulfur compound | Allium stipitatuma | increased intracellular Zn2+ level (3-fold increase at EC of 10 μM) | Cell-based assay (Radioactive Zn2+ uptake) | 96 |

| Quercetin | Flavonoid | Allium cepaa | increased intracellular Zn2+ level (18-fold increase at EC of 50 μM) | Cell-free assay (using liposome model) | 60 |

| increased the uptake of Zn2+ in both cell (2-fold increase at EC of 100 μM) and liposome model (8-fold increase at EC of 10 μM) | Cell-based assay (Fluorescent Zn2+ indicator) and cell-free assay (using liposome model) | [62] | |||

| Resveratrol | Polyphenol | Vitis viniferaa | increased intracellular Zn2+ level (7.5-fold increase at EC of 10 μM) | Cell-based assay (AAS) | 61 |

| Rutin | Flavonoid glycoside | Morus albaa | increased intracellular Zn2+ level (4-fold increase at EC of 50 μM) | Cell-free assay (using liposome model) | 60 |

| Tannic acid | Phenolic acid | Camellia sinensisa | increased intracellular Zn2+ level (12-fold increase at EC of 50 μM) | Cell-free assay (using liposome model) | 60 |

| Taxifolin | Flavonoid | Silybum marianuma | increased intracellular Zn2+ level (4-fold increase at EC of 50 μM) | Cell-free assay (using liposome model) | 60 |

| β-thujaplicin (Hinokitiol) | Terpene | Chamaecyparis obtusea | increased intracellular Zn2+ level (3-fold increase at EC of 125 μM) | Cell-based assay (Radioactive Zn2+ uptake) | 96 |

| Inhibiting the viroporin 3a activity | |||||

| Afzelin | Flavonoid glycoside | Houttuynia cordataa | inhibited the ion channel activity of SARS-CoV 3a protein (17% inhibition at EC of 10 μM) | Cell-based assay (Voltage-clamp method in Xenopus oocyte model) | 65 |

| Emodin | Anthraquinone | Rheum tanguticum | inhibited the ion channel activity of SARS-CoV 3a protein with IC50 of 20 μM | Cell-based assay (Voltage-clamp method in Xenopus oocyte model) | 66,97 |

| Juglanine | Flavonoid glycoside | Polygonum avicularea | inhibited the ion channel activity of SARS-CoV 3a protein with IC50 of 2.3 μM | Cell-based assay (Voltage-clamp method in Xenopus oocyte model) | 65 |

| Kaempferol | Flavonoid | Zingiber officinalea | inhibited the ion channel activity of SARS-CoV 3a protein (18% inhibition at EC of 20 μM) | Cell-based assay (Voltage-clamp method in Xenopus oocyte model) | 65,66 |

| Kaempferol-3-O-α-rhamnopyranosyl (1 → 2) [α-rhamno pyranosyl(1 → 6)]-β-glucopyranoside | Flavonoid glycoside | Clitoria ternateaa | inhibited the ion channel activity of SARS-CoV 3a protein (32% inhibition at EC of 20 μM) | Cell-based assay (Voltage-clamp method in Xenopus oocyte model) | 65 |

| Tiliroside | Flavonoid glycoside | Althaea officinalisa | inhibited the ion channel activity of SARS-CoV 3a protein (52% inhibition at EC of 20 μM) | Cell-based assay (Voltage-clamp method in Xenopus oocyte model) | 65,66 |

| Inhibiting the ACE activity | |||||

| 25-O-methylalisol F | Triterpenoid | Alisma orientale | Reduced ACE and AT1R protein expression (∼30% and ∼10% inhibition at EC of 10 μM) | Cell-based assay (WB analysis) | 98 |

| 3,5-dihydroxy-4- methoxybenzoic acid | Phenolic acid | Tamarix hohenackeri | 46.2% inhibition at EC of 20 mg/mL | Cell-free assay (HHL degradation assay) | 99 |

| 4′-hydroxy Pd-C-III | Coumarin | Angelica decursiva | IC50 = 9.4 μM | Cell-free assay (FAPGG degradation assay) | 100 |

| 4′-methoxy Pd–C–I | Coumarin | Angelica decursiva | IC50 = 16 μM | Cell-free assay (FAPGG degradation assay) | 100 |

| Ampleopsin C | Stilbenoid | Vitis thunbergii var. Taiwanian | IC50 = 18.2 μM | Cell-free assay (FAPGG degradation assay) | 101 |

| Apigenin | Flavonoid | Adinandra nitidaa | 30.3% inhibition at EC of 500 μg/mL | Cell-free assay (HHL degradation assay) | 102 |

| Asparaptine | Organic sulfur compound | Asparagus officinalis | IC50 = 113 μM | Cell-free assay (3HB-GGG hydrolysis assay) | 103 |

| Caffeic acid | Phenolic acid | Echinacea purpureaa | IC50 = 0.1 μM | Cell-free assay (HHL degradation assay) | 71 |

| Camellianin A | Flavonoid | Adinandra nitida | 30.2% inhibition at EC of 500 μg/mL | Cell-free assay (HHL degradation assay) | 102 |

| Camellianin B | Flavonoid | Adinandra nitida | 40.7% inhibition at EC of 500 μg/mL | Cell-free assay (HHL degradation assay) | 102 |

| Carlinoside | Flavonoid glycoside | Desmodium styracifolium | IC50 = 33.6 μM | Cell-free assay (HHL degradation assay) | 104 |

| Catechin | Flavonoid | Malus domestica(a) | IC50 = 109 μM | Cell-free assay (HHL degradation assay) | 105 |

| Chlorogenic acid | Phenolic acid | Echinacea purpurea(a) | IC50 = 0.1 μM | Cell-free assay (HHL degradation assay) | 71 |

| Chrysin | Flavonoid | Malus domestica(a) | IC50 = 146 μM | Cell-free assay (HHL degradation assay) | 105 |

| Chrysoeriol | Flavonoid | Tamarix hohenackeri | 57.6% inhibition at EC of 20 mg/mL | Cell-free assay (HHL degradation assay) | 99 |

| Coretincone | Phenolic glycoside | Coreopsis tinctoria | IC50 = 228 μM | Cell-free assay (HHL degradation assay) | 106 |

| Curcumin | Polyphenol | Curcuma longa(a) | 76.9% inhibition at EC of 10 μM | Cell-free assay (HHL degradation assay) | 107 |

| Cyanidin-3-O-glucoside | Flavonoid glycoside | Malus domestica(a) | IC50 = 174 μM | Cell-free assay (HHL degradation assay) | 105 |

| Cyanidin-3-O-galactoside | Flavonoid glycoside | Malus domestica(a) | IC50 = 206 μM | Cell-free assay (HHL degradation assay) | 105 |

| Cyanidin-3-O-rhamnosdie | Flavonoid glycoside | Malus domestica(a) | IC50 = 114 μM | Cell-free assay (HHL degradation assay) | 105 |

| Cyanidin-3-O-sambubioside | Flavonoid glycoside | Hibiscus sabdariffa | IC50 = 117.7 μM | Cell-free assay (FAPGG degradation assay) | 108 |

| Cyanidin-3-O-β-glucoside | Flavonoid glycoside | Rosa damascena | IC50 = 138.8 μM | Cell-free assay (HHL degradation assay) | 109 |

| Decursidin | Coumarin | Angelica decursiva | IC50 = 20 μM | Cell-free assay (FAPGG degradation assay) | 100 |

| (+)-trans-Decursidinol | Coumarin | Angelica decursiva | IC50 = 4.7 μM | Cell-free assay (FAPGG degradation assay) | 100 |

| Decursinol | Coumarin | Angelica decursiva | IC50 = 18.3 μM | Cell-free assay (FAPGG degradation assay) | 100 |

| Delphinidin-3-O-sambubioside | Flavonoid glycoside | Hibiscus sabdariffa | IC50 = 141.6 μM | Cell-free assay (FAPGG degradation assay) | 108 |

| Epicatechin | Flavonoid | Malus domestica(a) | IC50 = 73 μM | Cell-free assay (HHL degradation assay) | 105 |

| Gallic acid | Phenolic acid | Tamarix hohenackeri | 43.1% inhibition at EC of 20 mg/mL | Cell-free assay (HHL degradation assay) | 99 |

| Gluco-aurantioobtusin | Anthraquinone glycoside | Cassia tora | IC50 = 30.2 μM | Cell-free assay (FAPGG degradation assay) | 110 |

| (+)-Hopeaphenol | Stilbenoid | Ampelopsis brevipedunculata var. hancei | IC50 = 1.6 μM | Cell-free assay (HHL degradation assay) | 72 |

| Isoferulic acid | Phenolic acid | Tamarix hohenackeri | 30.6% inhibition at EC of 20 mg/mL | Cell-free assay (HHL degradation assay) | 99 |

| Isoquercetrin | Flavonoid | Tropaeolum majus(a) | Reduced plasmatic ACE activity in SHR rats (43% inhibition at EC of 10 mg/kg) | Cell-free assay (HHL degradation assay) | 111 |

| Isorutarine | Coumarin | Angelica decursiva | IC50 = 68.4 μM | Cell-free assay (FAPGG degradation assay) | 100 |

| Junipediol A-8-O-β-d-glucoside | Phenylpropa-noid glycoside | Apium graveolens | IC50 = 210 μM | Cell-free assay (HHL degradation assay) | 112 |

| (S)-Malic acid 1′-O-β-gentiobioside | Organic acid glycoside | Lactuca sativa | IC50 = 27.8 μM | Cell-free assay (HHL degradation assay) | 113 |

| Mangiferin | Xanthone glycoside | Swertia chirayita(a) | 31.5% inhibition at EC of 500 μM | Cell-free assay (HHL degradation assay) | 114 |

| Miquelianin | Flavonoid glycoside | Cuphea glutinosa | 32.1% inhibition at EC of 100 ng/mL | Cell-free assay (FAPGG degradation assay) | 115 |

| N1,N4,N8-tris (dihydrocaffeoyl)spermidine | Polyamine | Solanum quitoense | IC50 = 9.6 ppm | Cell-free assay (3HB-GGG hydrolysis assay) | 116 |

| Methyl gallate | Phenolic acid | Tamarix hohenackeri | 35.7% inhibition at EC of 20 mg/mL | Cell-free assay (HHL degradation assay) | 99 |

| Naringenin | Flavonoid | Malus domestica(a) | IC50 = 78 μM | Cell-free assay (HHL degradation assay) | 105 |

| Onopordia | Polyphenol | Onopordum acanthium L. | IC50 = 300 μM | Cell-free assay (HHL degradation assay) | 117,118 |

| Orotic acid | Organic acid | Daucus carota(a) | 40.3% inhibition at EC of 5 μg/mL | Cell-free assay (HHL degradation assay) | 119 |

| Pd–C–I | Coumarin | Angelica decursiva | IC50 = 6.8 μM | Cell-free assay (FAPGG degradation assay) | 100 |

| Pd-C-II | Coumarin | Angelica decursiva | IC50 = 12.4 μM | Cell-free assay (FAPGG degradation assay) | 100 |

| Pd-C-III | Coumarin | Angelica decursiva | IC50 = 15.3 μM | Cell-free assay (FAPGG degradation assay) | 100 |

| Quercetin | Flavonoid | Malus domestica(a) | IC50 = 151 μM | Cell-free assay (HHL degradation assay) | 105 |

| Tamarix hohenackeri | 48.6% inhibition at EC of 20 mg/mL | Cell-free assay (HHL degradation assay) | 99 | ||

| Quercetin-3-O-galactoside | Flavonoid glycoside | Malus domestica(a) | IC50 = 180 μM | Cell-free assay (HHL degradation assay) | 105 |

| Quercetin-3-O-glucoside | Flavonoid glycoside | Malus domestica(a) | IC50 = 71 μM | Cell-free assay (HHL degradation assay) | 105 |

| Quercetin-3-O-glucuronic acid | Flavonoid conjugate | Malus domestica(a) | IC50 = 27 μM | Cell-free assay (HHL degradation assay) | 105 |

| Quercetin-3-O-rhamnoside | Flavonoid glycoside | Malus domestica(a) | IC50 = 100 μM | Cell-free assay (HHL degradation assay) | 105 |

| Quercetin-3-O-rutinoside | Flavonoid glycoside | Malus domestica(a) | IC50 = 90 μM | Cell-free assay (HHL degradation assay) | 105 |

| Quercetin-3-O-sulfate | Flavonoid conjugate | Malus domestica(a) | IC50 = 131 μM | Cell-free assay (HHL degradation assay) | 105 |

| Quercetin-4′-O-glucoside | Flavonoid glycoside | Malus domestica(a) | IC50 = 211 μM | Cell-free assay (HHL degradation assay) | 105 |

| Schaftoside | Flavonoid glycoside | Desmodium styracifolium | IC50 = 58.4 μM | Cell-free assay (HHL degradation assay) | 104 |

| Tannic acid | Phenolic acid | Camellia sinensis(a) | IC50 = 230 μM | Cell-free assay (HHL degradation assay) | 120 |

| Taxifolin | Flavonoid | Coreopsis tinctoria | IC50 = 145.7 μM | Cell-free assay (HHL degradation assay) | 106 |

| Vicenin 1 | Flavonoid glycoside | Desmodium styracifolium | IC50a52.5 μM | Cell-free assay (HHL degradation assay) | 104 |

| Vicenin 2 | Flavonoid glycoside | Desmodium styracifolium | IC50 = 43.8 μM | Cell-free assay (HHL degradation assay) | 104 |

| Vicenin 3 | Flavonoid glycoside | Desmodium styracifolium | IC50 = 46.9 μM | Cell-free assay (HHL degradation assay) | 104 |

| (+)-ε-Viniferin | Stilbenoid | Vitis thunbergii var. taiwanian | IC50 = 35.5 μM | Cell-free assay (FAPGG degradation assay) | 101 |

| (+)-Vitisin A | Stilbenoid | Vitis thunbergii var. taiwanian | IC50 = 3.3 μM | Cell-free assay (FAPGG degradation assay) | 101 |

| Ampelopsis brevipedunculata var. hancei | IC50 = 1.5 μM | Cell-free assay (HHL degradation assay) | 72 | ||

3HB-GGG = 3-hydryoxybutyryl-Gly-Gly-Gly; AAS = Atomic absorption spectrophotometry; AO = Acridine orange; ATP = Adenosine triphosphate; DQ-BSA = Dye quenched-bovine serum albumin; EC = The effective test concentration; ELISA = Enzyme Linked Immunosorbent Assay; FAC/MS = Frontal affinity chromatography-Mass spectrometry; FAPGG = furylacryloyl-phenylalanyl-glycyl-glycine; FRET = Fluorescence resonance energy transfer; HHL = hippuryl-L-histidyl-l-leucine; IC50 = The half maximal inhibitory concentration; IFA = Immunofluorescence assay; SHR = spontaneously hypertensive rat; WB = WesternBlot.

The study used commercial products. Here provides a natural source of compound as an example.

3.1.2. The plasma membrane protease TMPRSS2

Recognized as a host trypsin-like serine protease, TMPRSS2 highly expressed in alveolar cells has been demonstrated to facilitate viral entry by priming of viral S protein. Inhibition of TMPRSS2 activity could prevent infection of coronaviruses including MERS-CoV, SARS-CoV and SARS-CoV-2.31 Now, several synthetic drugs like camostat mesylate, nafamostat mesylate and bromhexine which are serine protease inhibitors showed potential to inhibit SARS-CoV-2 infection.32, 33, 34 However, on the side of natural products, only few compounds were reported. Xanthoangelol G isolated from Angelica keiskei was reported to inhibit a trypsin-like serine protease with its IC50 value of 51.6 μM.35 Notably, in vitro cell-based and in vivo experiments are needed to be done for the development of anti-SARS-CoV-2 drugs.

3.1.3. The endocytic machinery

Clathrin-mediated endocytosis has been recognized as the primary cell entry route for multiple coronaviruses, including new emerging SARS-CoV-2, by utilizing the binding of viral S protein to host receptor ACE2 molecule.36 After endocytosis into the target cell, the viral particle undergoes the cleavage of S protein mediated by a pH-dependent cysteine protease cathepsin L at an acidic endolysosomal pH (∼3.0–6.5), which finally triggers membrane fusion between virus and endosome, followed by release of viral genetic material into the cytoplasm. Hence, targeting endocytic pathway-associated proteins are considered to be one of promising strategies for inhibiting SARS-CoV-2 entry.37 Following this idea, Table 1 summarizes natural compounds that have been reported with inhibitory effects on the vacuolar-type H+-ATPase (V-ATPase) activity, the expression and activity of cathepsins, or an increasing effect on lysosomal pH, which lead to impaired acidification and protein degradation of intracellular vesicles like endolysosome. Our search revealed that terpenes/terpenoids38, 39, 40, 41 and alkaloids42, 43, 44 are two major classes of compounds acting through this strategy. In addition to individual compounds, some crude plant extracts have shown their potential for being developed as an anti-COVID-19 drug. The traditional Japanese herbal formulation named Maoto, prepared from a mixture of four plants (Ephedrae herba, Armeniacae semen, Cinnamomi cortex and Glycyrrhizae radix), was recently shown to inhibit endolysosomal acidification.45 Zhuang et al. also demonstrated that butanol crude fraction from C. cortex was able to inhibit the clathrin-dependent endocytosis pathway as well as the infection of SARS-CoV using cell-based assays.46

3.2. Natural bioactive compounds targeting viral replication

3.2.1. The 3-chymotrypsin-like main protease (3CLpro)

The 3CLpro is an enzyme that plays important role in replication of coronaviruses. It is responsible for the cleavage of polyproteins to functional proteins. Base on the protein structures, 3CLpro of SARS-CoV and SARS-CoV-2 show similarity of amino acid sequence at 96%, and both enzymes exhibit high conservation of active residues.47 Therefore, small molecules with SAR-CoV 3CLpro inhibitory activity may also inhibit 3CLpro of SARS-CoV-2. Numerous studies have revealed for plant and mushroom derived natural compounds that could suppress SARS-CoV replication by blocking 3CLpro activity with IC50 range from 8.3 to 92.4 μM in either cell-free or cell-based assays. Among them, hesperetin, a phenolic compound isolated from Isatis indigotica root exhibited the greatest inhibitory activity against SARS-CoV 3CLpro (IC50 = 8.3 μM) in an African green monkey kidney (Vero) cell line and this effective dose did not toxic to the cells (CC50 = 2.7 mM).48 Other phytochemical classes that have shown promise in the inhibition of this enzyme are lignoid, terpenoid, tanshinone and chalcone with IC50 less than 25 μM.35,49, 50, 51 Interestingly, the lignoid savinin was able to reduce both viral replication (Selective index > 667) and cytopathic effect on SARS-CoV-infected Vero E6 cells.49 The summary of bioactive compounds against SARS-CoV 3CLpro inhibitory activity is tabulated in Table 1. Regarding to the similarity between 3CLpro of SARS-CoV and SARS-CoV-2, these natural compounds are interesting substances to screen as inhibitors of SARS-CoV-2 3CLpro activity furthermore.

3.2.2. The papain-like protease (PLpro)

Similar to 3CLpro, the function of PLpro is essential for coronavirus replication by generating RTC through proteolytic processing of viral polyprotein. Hence, PLpro could be served as another attractive target of drug discovery for treatment of coronavirus infection, especially SARS-CoV-2. At present, there is no FDA approved PLpro inhibitor available, therefore identification of bioactive compounds from medicinal plants that specifically inhibit PLpro has been focused to develop a new class of anti-coronavirus drug. According to high similarity of protein sequences and active residues between SARS-CoV and SARS-CoV-2 PLpro (83%),47 the compounds that have been reported as inhibitors of SARS-CoV PLpro may also be effective against SARS-CoV-2. Table 1 lists many interesting compounds from natural sources that exhibited SARS-CoV PLpro inhibitory activity. The IC50 values of the compounds ranged from 0.8 to 19.3 μM, demonstrating their strong inhibitory potential. Among them, the cryptotanshinone and tanshinone IIA were regarded as two most excellent inhibitors.51

3.2.3. The replication/transcription complex (RTC)

The replication of full-length genomic RNA and the discontinuous transcription of subgenomic RNA transcripts are crucial for the production of new coronavirus particles inside the host cell. Both processes are mediated by the coronavirus RTC composed of multiple viral nsps including two key replicative enzymes like the RdRp (nsp12) and helicase (nsp13),52 which are now considered as potential targets for COVID-19 therapy. Considering a strikingly high homology of nucleotide sequence, amino acid sequence and protein structure between SARS-CoV and SARS-CoV-2 RdRp,53 the natural compounds with previous reports of inhibitory activities towards RdRp of SARS-CoV could also have the potential to suppress the activities of those enzymes of the SARS-CoV-2. It was shown that the water extract from Houttuynia cordata exhibited a dose-dependent inhibition on SARS-CoV RdRp activity with the highest decrease by 74% in the treatment of 800 μg/mL.54 That activity of H. cordata was confirmed in another study by Fung et al., along with Sinomenium acutum, Coriolus versicolor, Ganoderma lucidum and a traditional Chinese herbal formula Kwan Du Bu Fei Dang. Their IC50 values were 251.1, 198.6, 108.4, 41.9 and 471.3 μg/mL, respectively.55 The inhibitors of SARS-CoV helicase also serve as a potential drug candidate since this enzyme has a highly conserved sequence among coronaviruses and shares the similar structure to that of SARS-CoV-2.52 Herein, three plant-derived bioactive compounds that could be natural inhibitors of SARS-CoV-2 helicase are listed in Table 1.

3.2.4. The zinc ion

Zinc is an essential micronutrient that is required for various cellular metabolic processes, not only in human immunity but also in the replication of many viruses.56 Although Zinc ion (Zn2+) acts as a cofactor for several important viral enzymes such as RdRp, 3CLpro and PLpro, it is interesting that its high intracellular concentration was found to inhibit those enzyme activities of a variety of RNA viruses including SARS-CoV,56, 57, 58 thus leading to subsequent decrease in the production of new virions. Therefore, Zn2+ possesses antiviral properties through generating host immune responses and inhibiting viral replication. As of now, several researchers have suggested the use of Zn2+ ionophore, a compound that stimulates cellular import of Zn2+ (e.g., chloroquine and its derivatives), as a possible option for the treatment of COVID-19.59 In Table 1, we summarized some natural compounds with Zn2+ ionophore activity. The most promising compound is epigallocatechin-3-gallate (EGCG), followed by quercetin, luteolin, tannic acid and resveratrol.60, 61, 62

3.3. Natural bioactive compounds targeting viral release

3.3.1. The viroporin 3a

The viroporins are small, pore-forming, viral-encoded accessory proteins with ion channel activity that have been known to play an essential role in mediating several processes in the life cycle of many viruses, including coronaviruses.63 Viroporin 3a functions are strongly involved in the regulation of viral budding and release from infected cells.13 Interestingly, this protein was found unique to SARS-CoV and SARS-CoV-2 and not present in other known coronaviruses,64 thus the viroporin 3a protein can be an important potential therapeutic target for COVID-19. Summary of natural compounds with inhibitory effect on viroporin 3a activity is presented in Table 1. Schwarz et al. revealed that flavonoid compounds like kaempferol and its derivatives were capable of blocking the ion channel activity of SARS-CoV viroporin 3a protein. Among them, the most potent one is the glycoside juglanine, kaempferol 3-O-α-l-arabinopyranoside, exhibiting IC50 of 2.3 μM.65 Another kaempferol glycoside tiliroside and the anthraquinone emodin also showed good inhibitory activity with and IC50 of 20 μM.66

3.4. Natural bioactive compounds targeting inflammation-related pathogenesis

Upon binding to SARS-CoV-2 S protein, the ACE2 function is downregulated which leads to increased angiotensin II level and overactivation of the AT1R signaling, causing the deleterious effects associated with excessive inflammation on several tissues.67 Therefore, suppressing angiotensin II production by ACE inhibitors and blocking of AT1R by angiotensin-receptor blockers (ARBs) may be of benefit to ameliorate Ang II/AT1R-mediated inflammation in COVID-19 patients. Moreover, it was shown that an ARB could not only reduce AT1R activation, but also activate the AT2R, thus resulting in a production of vasodilation benefit.68

Currently, ACE inhibitors and ARBs are commonly prescribed in COVID-19 patients with severe symptoms. Even though risks of the use of hypertensive drugs were concerned, accumulating evidence has not suggested the association between the drugs and worse clinical outcomes.69,70 Interestingly, a great number of natural compounds have been identified as potent ACE inhibitors and ARBs. Given that there are minimal side effects of using drugs from natural sources, those compounds with potential activity should be considered and investigated. Bioactive compounds derived from natural sources which possess ACE inhibitory activity are summarized in Table 1. Among them, the excellent inhibitory properties against ACE were exerted by the phenolic caffeic acid and chlorogenic acid, and the stilbenoid hopeaphenol and vitisin A, with IC50 less than 2 μM.71,72 These two stilbenoids were also found to be resveratrol tetramers exhibiting multifaceted properties including anti-inflammation73 and antiviral infection as a potent inhibitor of hepatitis C virus helicase.74 However, only few compounds have shown the ability to block AT1R which one of them is [6]-gingerol, the major bioactive compounds present in Zingiber officinale. According to the report by Liu and colleagues, it could inhibit AT1R activity with IC50 of 8.2 μM as detected by cell-based calcium mobilization assay.75

3.5. Anti-SARS-CoV natural compounds with unidentified mechanism of action

Some natural occurring compounds have been reported their beneficial effect to inhibit SARS-CoV, even though their mechanisms of action have not yet been identified (Table 2). Accordingly, the compounds from those previous studies might also have a potency to inhibit COVID-19 infection. Using HIV/SARS-CoV S pseudovirus and wild-type SARS-CoV, three anthocyanins derived from Cinnamomi cortex, cinnamtannin B1, procyanidin A2 and procyanidin B1, were reported their inhibitory activities against the infection of both viruses, but at least not through the inhibition of clathrin-mediated endocytosis.46 This study also investigated the effects of some crude plant extracts and found that aqueous extract of Caryophylli Flos exhibited moderate inhibition to pseudovirus (IC50 = 58.8 μM) and wild-type virus (IC50 = 50.1 μM).46 In addition, the natural alkaloid lycorine, isolated from Lycoris radiate, has been suggested as an anti-SARS-CoV compound with an IC50 value of 15.7 nM.121

Table 2.

List of anti-SARS-CoV compounds from natural sources with unidentified mechanism of action.

| Compound | Class | Source | Biological action/Efficacy | Experiment | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cinnamtannin B1 | Flavonoid | Cinnamomi cortex | IC50 = 32.9 μM (HIV/SARS-CoV S pseudovirus) | Cell-based assay (Luciferase reporter assay) | 46 |

| IC50 = 32.9 μM (Wild-type SARS-CoV) | Cell-based assay (Plaque reduction assay) | ||||

| Lycorine | Crystalline alkaloid | Lycoris radiata | IC50 = 15.7 nM | Cell-based assay (CPE/MTS assay) | 121 |

| Procyanidin A2 | Flavonoid | Cinnamomi cortex | IC50 = 120.7 μM (HIV/SARS-CoV S pseudovirus) | Cell-based assay (Luciferase reporter assay) | 46 |

| IC50 = 29.9 μM (Wild-type SARS-CoV) | Cell-based assay (Plaque reduction assay) | ||||

| Procyanidin B1 | Flavonoid | Cinnamomi cortex | IC50 = 161.1 μM (HIV/SARS-CoV S pseudovirus) | Cell-based assay (Luciferase reporter assay) | 46 |

| IC50 = 41.3 μM (Wild-type SARS-CoV) | Cell-based assay (Plaque reduction assay) |

CPE/MTS = cytopathic effect-based MTS reduction; IC50 = the half maximal inhibitory concentration.

(a) The study used commercial products. Here provides a natural source of compound as an example.

4. Conclusion and further prospects

Emerged as the most devastating viral infection in this era for the human race, the COVID-19 pandemic has introduced “new normal” for changing life as we recognize it. As numbers of new COVID-19 infected cases are rising globally, disruption of the transmission chain to minimize this spread is seriously unavoidable. This rise in COVID-19 infection is hardly disrupted unless its infective mechanisms including entry, replication and release, and modification of RAAS can be properly eliminated by humans. Certainly, we are waiting for effective strategies including drugs and vaccines to fight against COVID-19. Due to the unavailability of drugs to treat this infection, natural compounds are a main area of anti-COVID-19 research discovery. Our review suggests that 24 natural compounds have showed their potential actions on multiple therapeutic targets, which should be further explored for anti-COVID-19 plant/mushroom-based medicines (Fig. 2). The classes of these phytochemical compounds include chalcones (n = 7), flavonoids (n = 5), tanshinones (n = 5), phenolic acids (n = 3), polyphenol (n = 1), anthraquinone (n = 1), diarylheptanoid (n = 1) and biphenylpropanoid (n = 1). Among them, a natural flavonoid quercetin is found as a lead candidate with its ability on the virus side to inhibit SARS-CoV S protein-ACE2 interaction, viral protease and helicase activities, as well as on the host cell side to inhibit ACE activity and increase intracellular zinc level, thus making it very promising to reduce the disease burden. Although it is previously speculated that certain ACE inhibitors with an increased activity of ACE2 receptor may indeed enhance viral infectivity, recent studies revealed no substantial association between increased risks of infection and ACE inhibitor medications.69,70 Therefore, it is worth noting that many potential mechanisms of anti-COVID-19 natural agents are required to carefully and substantially investigated. Together with proper proactive investments, it is our great hope that qualified natural compound-based medicines from promising leads described here will be developed as anti-COVID-19 soon to benefit the human race in this “new normal” era.

Fig. 2.

Chemical structures of natural compounds with potential antiviral properties against multiple therapeutic targets for COVID-19.

Taxonomy (classification by EVISE)

Emerging Infectious Disease, Viral Infection of Respiratory System, Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome Coronavirus, Cell culture, Molecular Biology, Traditional herbal medicine, Natural Product Analysis.

Declaration of competing interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Acknowledgments

This work was partially supported by Grant for Research, Ratchadaphiseksomphot Endowment Fund, Chulalongkorn University, Thailand.

Footnotes

Peer review under responsibility of The Center for Food and Biomolecules, National Taiwan University.

Contributor Information

Anchalee Prasansuklab, Email: anchalee.pr@chula.ac.th.

Atsadang Theerasri, Email: atsadang.the@gmail.com.

Panthakarn Rangsinth, Email: panthakarn.rangsinth@gmail.com.

Chanin Sillapachaiyaporn, Email: chanin.sill@gmail.com.

Siriporn Chuchawankul, Email: siriporn.ch@chula.ac.th.

Tewin Tencomnao, Email: tewin.t@chula.ac.th.

References

- 1.Who . 2020. Novel Coronavirus – China.https://www.who.int/csr/don/12-january-2020-novel-coronavirus-china/en/ [Google Scholar]

- 2.Zhu N., Zhang D., Wang W. A novel coronavirus from patients with pneumonia in China, 2019. N Engl J Med. 2020;382(8):727–733. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa2001017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Huang C., Wang Y., Li X. Clinical features of patients infected with 2019 novel coronavirus in Wuhan, China. Lancet. 2020;395(10223):497–506. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(20)30183-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Wang D., Hu B., Hu C. Clinical characteristics of 138 hospitalized patients with 2019 novel coronavirus-infected pneumonia in wuhan, China. J Am Med Assoc. 2020 doi: 10.1001/jama.2020.1585. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Jin Y.H., Cai L., Cheng Z.S. A rapid advice guideline for the diagnosis and treatment of 2019 novel coronavirus (2019-nCoV) infected pneumonia (standard version) Mil Med Res. 2020;7(1):4. doi: 10.1186/s40779-020-0233-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Singh A.K., Singh A., Singh R., Misra A. Hydroxychloroquine in patients with COVID-19: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Diabetes Metab Syndr. 2020;14(4):589–596. doi: 10.1016/j.dsx.2020.05.017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Taccone F.S., Gorham J., Vincent J.L. Hydroxychloroquine in the management of critically ill patients with COVID-19: the need for an evidence base. Lancet Respir Med. 2020 doi: 10.1016/S2213-2600(20)30172-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Fuzimoto A.D., Isidoro C. The antiviral and coronavirus-host protein pathways inhibiting properties of herbs and natural compounds - additional weapons in the fight against the COVID-19 pandemic? Journal of traditional and complementary medicine. 2020;10(4):405–419. doi: 10.1016/j.jtcme.2020.05.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Panyod S., Ho C.T., Sheen L.Y. Dietary therapy and herbal medicine for COVID-19 prevention: a review and perspective. Journal of traditional and complementary medicine. 2020;10(4):420–427. doi: 10.1016/j.jtcme.2020.05.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Lin L.T., Hsu W.C., Lin C.C. Antiviral natural products and herbal medicines. Journal of traditional and complementary medicine. 2014;4(1):24–35. doi: 10.4103/2225-4110.124335. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Wang H., Yang P., Liu K. SARS coronavirus entry into host cells through a novel clathrin- and caveolae-independent endocytic pathway. Cell Res. 2008;18(2):290–301. doi: 10.1038/cr.2008.15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Song Z., Xu Y., Bao L. From SARS to MERS, thrusting coronaviruses into the spotlight. Viruses. 2019;11(1) doi: 10.3390/v11010059. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Lu W., Zheng B.J., Xu K. Severe acute respiratory syndrome-associated coronavirus 3a protein forms an ion channel and modulates virus release. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2006;103(33):12540–12545. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0605402103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.South A.M., Brady T.M., Flynn J.T. ACE2 (Angiotensin-Converting enzyme 2), COVID-19, and ACE inhibitor and Ang II (angiotensin II) receptor blocker use during the pandemic: the pediatric perspective. Hypertension (Dallas, Tex.: 1979) 2020;76(1):16–22. doi: 10.1161/HYPERTENSIONAHA.120.15291. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Shete A. Urgent need for evaluating agonists of angiotensin-(1-7)/Mas receptor axis for treating patients with COVID-19. Int J Infect Dis : IJID : official publication of the International Society for Infectious Diseases. 2020;96:348–351. doi: 10.1016/j.ijid.2020.05.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Yang J., Petitjean S.J.L., Koehler M. Molecular interaction and inhibition of SARS-CoV-2 binding to the ACE2 receptor. Nat Commun. 2020;11(1):4541. doi: 10.1038/s41467-020-18319-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Lan J., Ge J., Yu J. Structure of the SARS-CoV-2 spike receptor-binding domain bound to the ACE2 receptor. Nature. 2020;581(7807):215–220. doi: 10.1038/s41586-020-2180-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Tortorici M.A., Veesler D. Structural insights into coronavirus entry. Adv Virus Res. 2019;105:93–116. doi: 10.1016/bs.aivir.2019.08.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Li F., Li W., Farzan M., Harrison S.C. Structure of SARS coronavirus spike receptor-binding domain complexed with receptor. Science (New York, N.Y.). 2005;309(5742):1864–1868. doi: 10.1126/science.1116480. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Lu L., Liu Q., Zhu Y. Structure-based discovery of Middle East respiratory syndrome coronavirus fusion inhibitor. Nat Commun. 2014;5:3067. doi: 10.1038/ncomms4067. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Wu C., Liu Y., Yang Y. Analysis of therapeutic targets for SARS-CoV-2 and discovery of potential drugs by computational methods. Acta Pharm Sin B. 2020 doi: 10.1016/j.apsb.2020.02.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Lu R., Zhao X., Li J. Genomic characterisation and epidemiology of 2019 novel coronavirus: implications for virus origins and receptor binding. Lancet. 2020;395(10224):565–574. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(20)30251-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Wan Y., Shang J., Graham R., Baric R.S., Li F. Receptor recognition by the novel coronavirus from wuhan: an analysis based on decade-long structural studies of SARS coronavirus. J Virol. 2020;94(7) doi: 10.1128/JVI.00127-20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Wrapp D., Wang N., Corbett K.S. Cryo-EM structure of the 2019-nCoV spike in the prefusion conformation. Science (New York, N.Y.) 2020;367(6483):1260–1263. doi: 10.1126/science.abb2507. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Chen Y., Guo Y., Pan Y., Zhao Z.J. Structure analysis of the receptor binding of 2019-nCoV. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2020;525(1):135–140. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2020.02.071. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Hamming I., Timens W., Bulthuis M.L., Lely A.T., Navis G., van Goor H. Tissue distribution of ACE2 protein, the functional receptor for SARS coronavirus. A first step in understanding SARS pathogenesis. J Pathol. 2004;203(2):631–637. doi: 10.1002/path.1570. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Ashraf U.M., Abokor A.A., Edwards J.M. SARS-CoV-2, ACE2 expression, and systemic organ invasion. Physiol Genom. 2020 doi: 10.1152/physiolgenomics.00087.2020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.The COVID-19 RISK and Treatments (CORIST) Collaboration. Use of hydroxychloroquine in hospitalised COVID-19 patients is associated with reduced mortality: findings from the observational multicentre Italian CORIST study. Eur J Intern Med. 2020;82:38–47. doi: 10.1016/j.ejim.2020.08.019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Ho T.Y., Wu S.L., Chen J.C., Li C.C., Hsiang C.Y. Emodin blocks the SARS coronavirus spike protein and angiotensin-converting enzyme 2 interaction. Antivir Res. 2007;74(2):92–101. doi: 10.1016/j.antiviral.2006.04.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Yi L., Li Z., Yuan K. Small molecules blocking the entry of severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus into host cells. J Virol. 2004;78(20):11334–11339. doi: 10.1128/JVI.78.20.11334-11339.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.McKee D.L., Sternberg A., Stange U., Laufer S., Naujokat C. Candidate drugs against SARS-CoV-2 and COVID-19. Pharmacol Res. 2020:104859. doi: 10.1016/j.phrs.2020.104859. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Hoffmann M., Kleine-Weber H., Schroeder S. SARS-CoV-2 cell entry depends on ACE2 and TMPRSS2 and is blocked by a clinically proven protease inhibitor. Cell. 2020 doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2020.02.052. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Wang M., Cao R., Zhang L. Remdesivir and chloroquine effectively inhibit the recently emerged novel coronavirus (2019-nCoV) in vitro. Cell Res. 2020;30(3):269–271. doi: 10.1038/s41422-020-0282-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Maggio R., Gu Corsini. Repurposing the mucolytic cough suppressant and TMPRSS2 protease inhibitor bromhexine for the prevention and management of SARS-CoV-2 infection. Pharmacol Res. 2020 doi: 10.1016/j.phrs.2020.104837. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Park J.-Y., Ko J.-A., Kim D.W. Chalcones isolated from Angelica keiskei inhibit cysteine proteases of SARS-CoV. J Enzym Inhib Med Chem. 2016;31(1):23–30. doi: 10.3109/14756366.2014.1003215. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Inoue Y., Tanaka N., Tanaka Y. Clathrin-dependent entry of severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus into target cells expressing ACE2 with the cytoplasmic tail deleted. J Virol. 2007;81(16):8722–8729. doi: 10.1128/JVI.00253-07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Yang N., Shen H.M. Targeting the endocytic pathway and autophagy process as a novel therapeutic strategy in COVID-19. Int J Biol Sci. 2020;16(10):1724–1731. doi: 10.7150/ijbs.45498. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Barquero A.A., Alché L.E., Coto C.E. Block of vesicular stomatitis virus endocytic and exocytic pathways by 1-cinnamoyl-3,11-dihydroxymeliacarpin, a tetranortriterpenoid of natural origin. J Gen Virol. 2004;85(Pt 2):483–493. doi: 10.1099/vir.0.19343-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Sun H., Huang M., Yao N. The cycloartane triterpenoid ADCX impairs autophagic degradation through Akt overactivation and promotes apoptotic cell death in multidrug-resistant HepG2/ADM cells. Biochem Pharmacol. 2017;146:87–100. doi: 10.1016/j.bcp.2017.10.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Kuzu O.F., Gowda R., Sharma A., Robertson G.P. Leelamine mediates cancer cell death through inhibition of intracellular cholesterol transport. Mol Canc Therapeut. 2014;13(7):1690–1703. doi: 10.1158/1535-7163.MCT-13-0868. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Martins B.X., Arruda R.F., Costa G.A. Myrtenal-induced V-ATPase inhibition - a toxicity mechanism behind tumor cell death and suppressed migration and invasion in melanoma. Biochim Biophys Acta Gen Subj. 2019;1863(1):1–12. doi: 10.1016/j.bbagen.2018.09.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Wu M.Y., Wang S.F., Cai C.Z. Natural autophagy blockers, dauricine (DAC) and daurisoline (DAS), sensitize cancer cells to camptothecin-induced toxicity. Oncotarget. 2017;8(44):77673–77684. doi: 10.18632/oncotarget.20767. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Wang Z., Zhang J., Wang Y. Matrine, a novel autophagy inhibitor, blocks trafficking and the proteolytic activation of lysosomal proteases. Carcinogenesis. 2013;34(1):128–138. doi: 10.1093/carcin/bgs295. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Qiu W., Su M., Xie F. Tetrandrine blocks autophagic flux and induces apoptosis via energetic impairment in cancer cells. Cell Death Dis. 2014;5(3):e1123. doi: 10.1038/cddis.2014.84. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Masui S., Nabeshima S., Ajisaka K. Maoto, a traditional Japanese herbal medicine, inhibits uncoating of influenza virus. Evid base Compl Alternative Med : eCAM. 2017;2017:1062065. doi: 10.1155/2017/1062065. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Zhuang M., Jiang H., Suzuki Y. Procyanidins and butanol extract of Cinnamomi Cortex inhibit SARS-CoV infection. Antivir Res. 2009;82(1):73–81. doi: 10.1016/j.antiviral.2009.02.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Liu W., Morse J.S., Lalonde T., Xu S. Learning from the past: possible urgent prevention and treatment options for severe acute respiratory infections caused by 2019-nCoV. Chembiochem : a European journal of chemical biology. 2020 doi: 10.1002/cbic.202000047. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Lin C.-W., Tsai F.-J., Tsai C.-H. Anti-SARS coronavirus 3C-like protease effects of Isatis indigotica root and plant-derived phenolic compounds. Antivir Res. 2005;68(1):36–42. doi: 10.1016/j.antiviral.2005.07.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Wen C.-C., Kuo Y.-H., Jan J.-T. Specific plant terpenoids and lignoids possess potent antiviral activities against severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus. J Med Chem. 2007;50(17):4087–4095. doi: 10.1021/jm070295s. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Liu Y.-P., Cai X.-H., Feng T., Li Y., Li X.-N., Luo X.-D. Triterpene and sterol derivatives from the roots of Breynia fruticosa. J Nat Prod. 2011;74(5):1161–1168. doi: 10.1021/np2000914. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Park J.-Y., Kim J.H., Kim Y.M. Tanshinones as selective and slow-binding inhibitors for SARS-CoV cysteine proteases. Bioorg Med Chem. 2012;20(19):5928–5935. doi: 10.1016/j.bmc.2012.07.038. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Romano M., Ruggiero A., Squeglia F., Maga G., Berisio R. A structural view of SARS-CoV-2 RNA replication machinery: RNA synthesis, proofreading and final capping. Cells. 2020;9(5) doi: 10.3390/cells9051267. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Morse J.S., Lalonde T., Xu S., Liu W.R. Learning from the past: possible urgent prevention and treatment options for severe acute respiratory infections caused by 2019-nCoV. Chembiochem : a European journal of chemical biology. 2020;21(5):730–738. doi: 10.1002/cbic.202000047. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Lau K.M., Lee K.M., Koon C.M. Immunomodulatory and anti-SARS activities of Houttuynia cordata. J Ethnopharmacol. 2008;118(1):79–85. doi: 10.1016/j.jep.2008.03.018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Fung K.P., Leung P.C., Tsui K.W. Immunomodulatory activities of the herbal formula Kwan Du Bu Fei Dang in healthy subjects: a randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled study. Hong Kong medical journal = Xianggang yi xue za zhi. 2011;17(Suppl 2):41–43. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Read S.A., Obeid S., Ahlenstiel C., Ahlenstiel G. The role of zinc in antiviral immunity. Advances in nutrition (Bethesda, Md. 2019;10(4):696–710. doi: 10.1093/advances/nmz013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.te Velthuis A.J., van den Worm S.H., Sims A.C., Baric R.S., Snijder E.J., van Hemert M.J. Zn(2+) inhibits coronavirus and arterivirus RNA polymerase activity in vitro and zinc ionophores block the replication of these viruses in cell culture. PLoS Pathog. 2010;6(11) doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1001176. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Kaushik N., Subramani C., Anang S. Zinc salts block hepatitis E virus replication by inhibiting the activity of viral RNA-dependent RNA polymerase. J Virol. 2017;91(21) doi: 10.1128/JVI.00754-17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Rahman M.T., Idid S.Z. Can Zn Be a critical element in COVID-19 treatment? Biol Trace Elem Res. 2020:1–9. doi: 10.1007/s12011-020-02194-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Clergeaud G., Dabbagh-Bazarbachi H., Ortiz M., Fernández-Larrea J.B., O’Sullivan C.K. A simple liposome assay for the screening of zinc ionophore activity of polyphenols. Food Chem. 2016;197(Pt A):916–923. doi: 10.1016/j.foodchem.2015.11.057. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Zhang J.J., Wu M., Schoene N.W. Effect of resveratrol and zinc on intracellular zinc status in normal human prostate epithelial cells. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol. 2009;297(3):C632–C644. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.00139.2009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Dabbagh-Bazarbachi H., Clergeaud G., Quesada I.M., Ortiz M., O’Sullivan C.K., Fernández-Larrea J.B. Zinc ionophore activity of quercetin and epigallocatechin-gallate: from Hepa 1-6 cells to a liposome model. J Agric Food Chem. 2014;62(32):8085–8093. doi: 10.1021/jf5014633. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Sze C.W., Tan Y.J. Viral membrane channels: role and function in the virus life cycle. Viruses. 2015;7(6):3261–3284. doi: 10.3390/v7062771. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Yu C.J., Chen Y.C., Hsiao C.H. Identification of a novel protein 3a from severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus. FEBS Lett. 2004;565(1-3):111–116. doi: 10.1016/j.febslet.2004.03.086. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Schwarz S., Sauter D., Wang K. Kaempferol derivatives as antiviral drugs against the 3a channel protein of coronavirus. Planta Med. 2014;80(2-3):177–182. doi: 10.1055/s-0033-1360277. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Schwarz S., Sauter D., Lu W. vol. 3. 2012. pp. 1–13. (Coronaviral Ion Channels as Target for Chinese Herbal Medicine). 1. [Google Scholar]

- 67.Banu N., Panikar S.S., Leal L.R., Leal A.R. Protective role of ACE2 and its downregulation in SARS-CoV-2 infection leading to Macrophage Activation Syndrome: therapeutic implications. Life Sci. 2020;256:117905. doi: 10.1016/j.lfs.2020.117905. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Alexandre J., Cracowski J.L., Richard V., Bouhanick B. Renin-angiotensin-aldosterone system and COVID-19 infection. Ann Endocrinol. 2020;81(2-3):63–67. doi: 10.1016/j.ando.2020.04.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Mancia G., Rea F., Ludergnani M., Apolone G., Corrao G. Renin-angiotensin-aldosterone system blockers and the risk of covid-19. N Engl J Med. 2020 doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa2006923. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Reynolds H.R., Adhikari S., Pulgarin C. Renin-angiotensin-aldosterone system inhibitors and risk of covid-19. N Engl J Med. 2020 doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa2008975. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Chiou S.Y., Sung J.M., Huang P.W., Lin S.D. Antioxidant, antidiabetic, and antihypertensive properties of echinacea purpurea flower extract and caffeic acid derivatives using in vitro models. J Med Food. 2017;20(2):171–179. doi: 10.1089/jmf.2016.3790. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Su P.S., Doerksen R.J., Chen S.H. Screening and profiling stilbene-type natural products with angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitory activity from Ampelopsis brevipedunculata var. hancei (Planch.) Rehder. J Pharmaceut Biomed Anal. 2015;108:70–77. doi: 10.1016/j.jpba.2015.01.053. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Mi Jeong S., Davaatseren M., Kim W. Vitisin A suppresses LPS-induced NO production by inhibiting ERK, p38, and NF-kappaB activation in RAW 264.7 cells. Int Immunopharm. 2009;9(3):319–323. doi: 10.1016/j.intimp.2008.12.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]