Abstract

Objective

Information from critically ill coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) patients is limited and in many cases coming from health systems approaches different from the national public systems existing in most countries in Europe. Besides, patient follow-up remains incomplete in many publications. Our aim is to characterize acute respiratory distress syndrome (ARDS) patients admitted to a medical critical care unit (MCCU) in a referral hospital in Spain.

Design

Retrospective case series of consecutive ARDS COVID-19 patients admitted and treated in our MCCU.

Setting

36-bed MCCU in referral tertiary hospital.

Patients and participants

SARS-CoV-2 infection confirmed by real-time reverse transcriptase–polymerase chain reaction (RT-PCR) assay of nasal/pharyngeal swabs.

Interventions

None

Main variables of interest

Demographic and clinical data were collected, including data on clinical management, respiratory failure, and patient mortality.

Results

Forty-four ARDS COVID-19 patients were included in the study. Median age was 61.50 (53.25 – 67) years and most of the patients were male (72.7%). Hypertension and dyslipidemia were the most frequent co-morbidities (52.3 and 36.4% respectively). Steroids (1mg/Kg/day) and tocilizumab were administered in almost all patients (95.5%). 77.3% of the patients needed invasive mechanical ventilation for a median of 16 days [11-28]. Prone position ventilation was performed in 33 patients (97%) for a median of 3 sessions [2-5] per patient. Nosocomial infection was diagnosed in 13 patients (29.5%). Tracheostomy was performed in ten patients (29.4%). At study closing all patients had been discharged from the CCU and only two (4.5%) remained in hospital ward. MCCU length of stay was 18 days [10-27]. Mortality at study closing was 20.5% (n 9); 26.5% among ventilated patients.

Conclusions

The seven-week period in which our MCCU was exclusively dedicated to COVID-19 patients has been challenging. Despite the severity of the patients and the high need for invasive mechanical ventilation, mortality was 20.5%.

Keywords: COVID-19, SARS-CoV-2, ARDS, Critical care, Viral pneumonia

Abstract

Objetivo

La información de pacientes críticos con enfermedad por coronavirus 2019 (COVID-19) es limitada y, en muchos casos, proviene de sistemas de salud diferentes a la organización pública de la mayoría de los países de Europa. Además, el seguimiento del paciente sigue siendo incompleto en muchas publicaciones. Nuestro objetivo es caracterizar a los pacientes con síndrome de distres respiratorio agudo (SDRA) ingresados en una unidad de cuidados críticos médicos (MCCU) en un hospital de referencia en España.

Diseño

Serie retrospectiva de casos de pacientes consecutivos con SDRA por COVID-19 ingresados y tratados en nuestra MCCU.

Lugar

UCC de 36 camas en un hospital terciario de referencia

Pacientes y participantes

Infección por SARS-CoV-2 confirmada por ensayo en tiempo real de la transcriptasa inversa-reacción en cadena de la polimerasa (RT-PCR) de hisopos nasales/faríngeos.

Intervenciones

Ninguna

Principales variables de interés

Se recopilaron datos demográficos y clínicos, incluidos datos sobre manejo clínico, insuficiencia respiratoria y mortalidad del paciente.

Resultados

Cuarenta y cuatro pacientes con SDRA por COVID-19 fueron incluidos en el estudio. La mediana de edad fue de 61.50 (53.25 - 67) años y la mayoría de los pacientes eran hombres (72.7%). La hipertensión y la dislipidemia fueron las comorbilidades más frecuentes (52,3 y 36,4%, respectivamente). Se administraron esteroides (1mg/kg/día) y tocilizumab en casi todos los pacientes (95,5%). El 77,3% de los pacientes necesitaron ventilación mecánica invasiva durante una mediana de 16 días [11-28]. La ventilación en posición prono se realizó en 33 pacientes (97%) con una mediana de 3 sesiones [2-5] por paciente. Se diagnosticó una infección nosocomial en 13 pacientes (29,5%). La traqueotomía se realizó en diez pacientes (29,4%). Al cierre del estudio, todos los pacientes habían sido dados de alta de la MCCU y solo dos permanecían hospitalizados. La estancia en MCCU fue de 18 días [10-27]. La mortalidad al cierre del estudio fue del 20,5% (n 9); 26.5% para pacientes ventilados.

Conclusiones

El período de siete semanas en el que nuestra MCCU se dedicó exclusivamente a pacientes con COVID-19 ha sido un gran desafío. A pesar de la gravedad de los pacientes y la elevada necesidad de ventilación mecánica invasiva, la mortalidad fue del 20,5%.

Palabras clave: COVID-19, SARS-CoV-2, SDRA, Cuidados críticos, Neumonía viral

Introduction

Since the initial identification of SARS-CoV-2 in Wuhan the virus has worldwide widespread causing more than three million infected patients and more than two hundred and thousand deaths.1 Spain has become the most affected European country by the pandemic with more than two hundred and thousand people affected and a mortality rate currently situated at 11,3%.2 Consequently, critical care resources have been intensely exploited and clinical recommendations have been created.3 However, accurate information concerning critically ill COVID-19 patients is scarce and in most cases incomplete. Although national and local registers are underway, published series come mainly from China and USA.4, 5, 6, 7, 8, 9, 10 In those studies critical care unit (CCU) admission ranged from 7 to 14%, invasive mechanical ventilation was used in 29% to 75% of these critically ill patients and mortality of ventilated patients was extremely variable, ranging from 12% to 81%. Public and private health systems in those countries may differ considerably from our national approach and therefore epidemiological extrapolation is hazardous. Information coming from Italy seems to be more resembling to our situation; however 58% of the critically ill patients included in the Italian report were still in the CCU at the end of the follow-up.11 At this point, the reported mortality rate (26%) could undergo major changes.

This present study aimed at reporting a complete critically ill COVID-19 patient series from a CCU of a tertiary hospital, Hospital Universitario y Politécnico la Fe, from Valencian Community, Spain. Our main objective was to assess COVID-19 ARDS patient's management and prognosis. Valencian Community has nearly five million inhabitants and, unlike other areas of Spain, the expansion of SARS-CoV-2 has been moderate. Right now 11,254 people have been identified as positive to SARS-CoV-2 (225 positives every 100,000 habitants) and 601 patients have been admitted to CCUs.2 We present a detailed description and follow-up of all critically ill patients admitted to our medical critical care unit (MCCU).

Methods

Study population, setting and data collection

This is a retrospective, unicentric, and observational study.

Hospital Universitario y Politécnico la Fe has two critical care units for adults; a 36-bed medical critical care unit (MCCU) carried by intensivists and a 36-bed surgical critical care unit (SCCU) carried by anaesthesiologists in which patients recovering from surgery or severe trauma are admitted. Due to SARS-CoV-2 pandemics COVID-19 patients were also admitted to the SCCU once all MCCU beds were occupied.

MCCU has a rapid response service (RRS) that daily evaluates patients admitted to the ward and identifies those who, due to a high NEWS score punctuation, would be eligible for admission to the unit.12 During the SARS-CoV-2 pandemic, the RRS was reinforced with a second physician. Patient admission to the MCCU was guided by the major/minor ATS/IDSA criteria for severe community pneumonia.13

All consecutive SARS-CoV-2 positive patients (≥18 years old) admitted to our MCCU were included in the study. A confirmed case of COVID-19 was defined by a positive result on a reverse-transcriptase-polymerase-chain-reaction (RT-PCR) assay of a specimen collected from airway secretion or from a nasopharyngeal swab.14 The first patient was admitted on the 16th of March and the last one on the 9th of April 2020. Patients were followed until hospital discharge or death; study follow-up was closed 3rd of June. Patients were distinguished between those with clinical pneumonia due to SARS-CoV-2 and those who were admitted to MCCU because of other disease unrelated to SARS-CoV-2 positivity. Patients in whom ARDS diagnosis, management and prognosis could not be evaluated due to treatment withdrawal or very early death at CCU admission (<6 hours) were excluded from the final analysis.

We obtained demographic data, coexisting conditions information, data on clinical symptoms or signs at CCU admission and follow-up, and laboratory and radiological results during CCU stay. All laboratory and radiological assessments were performed at responsible physician discretion. COVID-19 treatments and life support measures were recorded.

Bacterial co-infection at hospital admission was assessed. Nosocomial infection and multi-drug resistant bacteria (MDRB) colonization was proactively sought during CCU stay according to a pre-established infection control program including weekly MDRB surveillance cultures.15 Infections due to opportunistic microorganisms were prospectively discarded in those patients with prolonged invasive mechanical ventilation (≥ one week) and signs or symptoms of respiratory or infectious deterioration of unclear origin.

Study definitions

Acute respiratory distress syndrome (ARDS) was defined as acute-onset hypoxemia (ratio of partial pressure of arterial oxygen to the fraction of inspired oxygen (PaO2/FiO2) < 300) with bilateral pulmonary opacities on chest imaging not explained by congestive heart failure. ARDS patients who required invasive mechanical ventilation were managed agreeing to the guidelines with a protective ventilation (tidal volume ≤6 ml/Kg, plateau pressure < 30 cmH2O and driving pressure < 15 cmH2O) and rescue therapies when necessary (prone position, recruitment manoeuvres, nitric oxide (NO) and/or extracorporeal membrane oxygenation (ECMO)).16

Nosocomial infections diagnosis was established according to the Centers for Disease Control criteria.17 Invasive pulmonary aspergillosis was diagnosed according to EORTC criteria modified by Blot et al for critically ill patients.18 CMV reactivation was identified by a clinical picture of sepsis/pneumonia besides the presence of >400 copies/ml in plasma or positive PCR in bronchoalveolar lavage.19 HSV pneumonia was diagnosed in the absence of other aetiology besides positivity for HSV PCR in alveolar fluid.20

Statistical analysis

Descriptive statistics were used to summarize the results; reported as means and standard deviations or medians and interquartile ranges, as appropriate. Categorical variables were expressed as counts and percentages. Categorical variables were compared using the Chi square test. Comparison of numerical variables was performed with the Mann–Whitney U test. The statistical significance was set at 0.05 (95% confidence interval). Analysis was performed with SPSS 16.0.

The study was approved by our hospital Ethical Committee and informed consent was waived due to the retrospective nature of the study.

Results

Demographic, clinical and laboratory characteristics

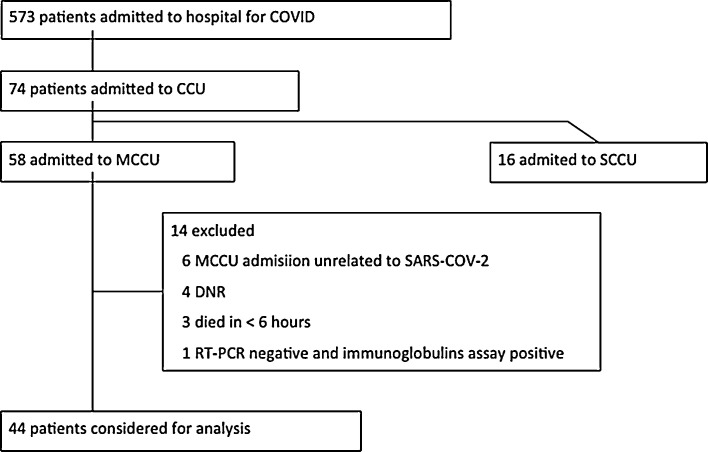

During the study period 573 patients were admitted to hospital for COVID-19 (at present 351 (61%) had been discharged, 88 (15%) had died and 150 (26%) remain hospitalized). Seventy-four (13%) patients were admitted to CCU; 58 to medical CCU and 16 to surgical CCU. Six patients were admitted to MCCU because of a disease unrelated to SARS-COV-2 positivity and therefore were excluded from the analysis. Four patients were initially admitted to MCCU and were suffering respiratory failure, but due to do not resuscitate orders (DNRO) supportive treatment was withdrawn because of the following situations: patient admitted because of traumatic brain injury who developed irreversible brain damage, patient with malignant hemopathy non-responding to quemotherapy, patient with severe co-morbidities who was not intubated and patient with irreversible post-anoxic encephalopathy due to cardiorespiratory arrest after iatrogenic haemopericardium. Three patients died in less of 6 hours because of haemorrhagic shock, fulminant myocarditis and non-responding asthma crisis respectively; ARDS diagnosis and management could not be evaluated and therefore these patients were not included. And one SDRA patient was RT-PCR negative in four different determinations and COVID-19 diagnosis was finally obtained by means of immunoglobulin assay (positive IgM and IgG followed by negative IgM/positive IgG); this patient was excluded from the analysis. Therefore, data concerning 44 patients admitted to MCCU under the care of intensivist will be presented in this study (Figure 1 ).

Figure 1.

COVID-19 patients treated in the hospital during the study period.

Demographic and clinical characteristics are depicted in Table 1 . Most patients were male (n 32, 72.7%), mean age was 61.5 [53.2-67]. Arterial hypertension (23, 52.3%), dyslipidaemia (16, 36.4%) and diabetes (6, 13.6%) were the most frequent co-morbidities. Time in days between the onset of symptoms and hospital admission was 6.5 [5-8] and between hospital admission and MCCU admission was 2 [0-4]. SAPS3 punctuation was 50 [43.5-59].

Table 1.

Demographic and clinical characteristics.

| All (n = 44) | IMV (n = 34) | HFNC (n = 10) | p | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age | 61.50 (53.25 – 67) | 62 (53.75 – 67.25) | 59.5 (48.5 – 63.75) | 0.320 |

| Male | 32 (72.7) | 25 (73.5) | 7 (70) | 0.826 |

| BMI | 29 (25.6 – 31) | 28.55 (24.5 – 31.1) | 29.7 (27.5 – 31) | 0.408 |

| Comorbidities | ||||

| Arterial hypertension | 23 (52.3) | 18 (52.9) | 5 (50) | 0.870 |

| Diabetes mellitus | 6 (13.6) | 5 (14.7) | 1 (10) | 0.703 |

| Dyslipidemia | 16 (36.4) | 13 (38.2) | 3 (30) | 0.634 |

| Chronic corticotherapy | 2 (4.5) | 2 (5.9) | 0 (0) | 0.432 |

| Immunodeficiency | 2 (4.5) | 2 (5.9) | 0 (0) | 0.432 |

| Pneumopathy | 5 (11.4) | 3 (8.8) | 2 (20) | 0.328 |

| Delay between onset of symptoms and hospitalization | 6.5 (5 – 8) | 6 (4 – 7.25) | 7.5 (6 – 9.25) | 0.050 |

| Delay between hospitalization and MCCU admission | 2 (0 – 4) | 1.5 (0 – 3.25) | 2 (1.75 – 5) | 0.142 |

| SAPS3 | 50 (43.50 – 59) | 53 (42.75 – 62.25) | 45.5 (44 – 49.25) | 0.052 |

| Norepinephrine | 28 (63.6) | 27 (79.4) | 1 (10) | < 0.001 |

| RRT | 1 (2.3) | 1 (2.9) | 0 (0) | 0.703 |

| MCCU stay | 14 (8 – 23.25) | 19 (13 – 25.75) | 6 (4.75 – 8.5) | < 0.001 |

| Hospital stay | 23 (15 – 28)* | 26 (19.29)* | 17.5 (14.25 – 22.5) | 0.079 |

| Mortality | 8 (18.1)* | 8 (23.5)* | 0 (0) | 0.080 |

Data expressed as mean ± standard deviation or number (%), unless otherwise specified. BMI, body mass index; HFNC, high flow nasal cannula; IMV, invasive mechanical ventilation; MCCU, Medical Critical Care Unit; RRT, renal replacement therapy; SAPS, Simplified Acute Physiology Score.

3 patients still remain at the MCCU.

Laboratory findings at MCCU admission are shown in Table 2 . Inflammatory biomarkers were elevated in most patients. However, only 8 patients (18.2%) presented with IL6 above 200 pg/ml. Five patients (11.4%) had procalcitonin (PCT) higher than 1ng/ml although none bacterial co-infection could be demonstrated in these patients. C-reactive protein (CRP) had a more homogeneous behaviour, all patients had values above the normal range and only 7 (16%) were below 100 mg/l. Ferritin was available only in four patients. Albumin below or equal to 3 g/dl was present in 8 patients (18.2%).

Table 2.

Laboratory findings at MCCU admission.

| All (n = 44) | IMV (n = 34) | HFNC (n = 10) | p | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| IL-6 (pg/ml) | 129.7 (65.9 – 209.45) | 136 (91.9 – 226.7) | 66.3 (46.7 – 139.5) | 0.022 |

| PCT (ng/ml) | 0.22 (0.14 – 0.6) | 0.23 (0.15 – 0.65) | 0.15 (0.06 – 0.34) | 0.298 |

| CPR (mg/l) | 212 (109.15 – 306.5) | 251.7 (142.9 – 330.2) | 115 (86 – 218.9) | 0.016 |

| Ferritin (ng/ml)* | 1,565 (798 – 2,251) | 1,897 (1,233 – 2,370)* | 653* | 0.180 |

| Albumin (g/dl) | 3.3 (3.15 – 3.6) | 3.3 (3 – 3.5) | 3.5 (3.35 – 3.75) | 0.065 |

| LDH (UI/L) | 426 (379.5 – 507) | 446 (381 – 524) | 411.5 (375.3 – 481.3) | 0.338 |

| Leukocytes(/mm3) | 7,330 (6,190 – 8,735) | 7,350 (6,620 – 9,060) | 6,685 (5,227 – 8,505) | 0.182 |

| Lymphocytes(/mm3) | 700 (535 – 825) | 690 (530 – 780) | 795 (635 – 1,037.5) | 0.121 |

| Platelets (/mm3) | 231,000 (173,000 – 279,000) | 206,000 (172,000 – 271,000) | 273,500 (244,500 – 301,750) | 0.036 |

| D-dimers (ng/ml) | 825 (509 – 1,282) | 1,034 (561.75 – 1,660) | 516 (329.5 – 812) | 0.007 |

Data expressed as mean ± standard deviation, unless otherwise specified. CPR, C-reactive protein; HFNC, high flow nasal cannula; IL-6, Interleukin 6; IMV, invasive mechanical ventilation; LDH, Lactate dehydrogenase; MCCU, Medical Critical Care Unit; PCT, procalcitonin.

Only available in four patients at MCCU admission, three from the IMV group and one from the HFNC group.

Lymphopenia (≤1000 cell/mm3) was detected in most of the patients (86.4%, n 38); severe lymphopenia (≤500 cell/mm3) occurred in 7 patients (16%). Thrombocytopenia (≤150.000 cell/mm3) was present in 7 patients but only one case had less than 100.000 cell/mm3. Augmented D-dimers (≥500 ng/ml) occurred in 28 patients (63.6%) but only 3 cases (6.8%) were higher than 3.000 ng/ml.

All patients had a bilateral diffuse infiltrate on the initial chest radiograph. Median PaO2:FiO2 ratio was 83 [60.6-117].

COVID-19 treatments and life support measures

Almost all patients were treated with chloroquine and azithromycine (100% and 95.5% respectively). Other treatments directed towards the virus are depicted in Table 3 . Immunomodulation was attempted in all patients except two (95.5%); steroids in 35 cases (79.5%) (≥1 mg/Kg/day in 93.2% of all treated patients), tocilizumab in 36 cases (81.8%) and baricitinib in 4 cases (9%). All patients were under prophylactic low molecular weight heparin and only two received therapeutic anticoagulant treatment due to the presence of an aortic prosthetic valve and to the development of a venous thrombosis related to the presence of a central catheter.

Table 3.

Treatment for COVID-19.

| All (n = 44) | IMV (n = 34) | HFNC (n = 10) | p | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Antiviral treatment | ||||

| Azithromycin | 42 (95.5) | 32 (94.1) | 10 (100) | 0.432 |

| Hidroxicloroquine | 44 (100) | 34 (100) | 10 (100) | - |

| Lopinavir/ritonavir | 31 (70.5) | 26 (76.5) | 5 (50) | 0.107 |

| Remdesivir | 3 (6.8) | 3 (8.8) | 0 (0) | 0.331 |

| Immunomodulatory treatment | ||||

| Baricitinib | 4 (9.1) | 2 (5.9) | 2 (20) | 0.172 |

| Corticosteroids | 35 (79.5) | 28 (82.4) | 7 (70) | 0.395 |

| Interferon β-1b | 27 (61.4) | 21 (61.8) | 6 (60) | 0.920 |

| Tocilizumab | 36 (81.8) | 29 (85.3) | 7 (70) | 0.432 |

| Vitamin C | 12 (27.3) | 10 (29.4) | 2 (20) | 0.557 |

Data expressed as number (%), unless otherwise specified. HFNC, high flow nasal cannula; IMV, invasive mechanical ventilation.

Thirty-four patients needed invasive mechanical ventilation (77.3%); of them 13 (38%) were intubated the same day they were admitted to the MCCU and 21 (67.8%) were intubated after a median of 2 [1-2] days of delay. Not intubated patients and those with a delay until intubation were supported with high flow nasal cannula (HFNC). None patient received non-invasive mechanical ventilation.

Among ventilated patients all coupled with moderate-severe ARDS definition (PaO2/FiO2 < 200). All mechanically ventilated patients received protective ventilation. Prone-position ventilation was performed in 33 patients (97%) (median of 3 sessions [2-5] per patient) achieving an improvement in oxygenation in all patients (at least temporarily), recruitment manoeuvres were realized in 25 patients (73.5%) and nitric oxide was administered to 7 patients (20.6%). Extracorporeal membrane oxygenation (ECMO) was used in 3 cases (8.8%); 2 veno-venous systems and 1 veno-arterial system because of heart failure.

Norepinephrine was used in 28 patients (63.6%) because of hypotension unresponsive to fluid administration (and avoiding fluid overload in SDRA context) but none of them attended with serum lactate > 2 mmol/l.

Only one patient under VA-ECMO needed extracorporeal renal replacement. However 36% of our patients (n 16) coupled with AKIN stage 1 criteria due to urine output < 0.5 ml/Kg during 6 hours. All patients responded to fluid administration and none of them progressed to more severe AKIN stages.

Microbiological and infectious diseases assessment

None bacterial co-infection could be demonstrated at hospital or ICU admission.

ICU-nosocomial infection was detected 16 times in 13 patients (29.5%). Ventilator-associated pneumonia (VAP) was the most common infection; 8 of 34 ventilated patients (23.5%). Ventilated-associated tracheobronchitis (TAVM) was diagnosed in 1 patient (2.9%). Catheter-related bacteraemia (CRB) occurred in three patients (6.8%) and primary bacteremia in one patient (2.3%). Most common aetiologies were: Pseudomonas aeruginosa (n 7; 46.7%), Staphylococcus aureus (n 3; 20%) and Escherichia coli (n 1; 6.7%). Opportunistic infections were diagnosed in 5 patients; 4 cases of HSV pneumonia (one of them co-infecting with CMV) and 1 pulmonary invasive aspergillosis.

Outcomes

At study closing all patients had been discharged from the CCU and only two (4.5%) remained in hospital ward. MCCU length of stay was 18 days [10-27] and hospital length of stay was 28 days [19-39]. Mortality at study closing was 20,5% (n 9). All deaths occurred in CCU after a median of 17 days [12-24]. If we include all COVID19 patients (SARS-CoV-2 positive without disease and patients with DNRO) mortality will rise to 28% (16 deaths in 57 patients).

Mechanical ventilation duration for the 34 ventilated patients was 16 days [11-28]. All ventilated patients were treated with neuromuscular blockers for a median of 5 days [3-14]. Tracheostomy was performed in ten patients (29.4%) after a median of 21 days [19.3-23.5]. Five patients (14.7%) presented spontaneous pneumothorax during mechanical ventilation. Mortality among ARDS ventilated patients was 26.5%. Death in ventilated patients occurred after a median of 17 days [12-24].

Four patients (9%) required readmission to the MCCU after discharge. Three of them presented haemorrhagic shock related with anticoagulation treatment and were managed with arterial embolization. The fourth patient was readmitted because of respiratory worsening due to pulmonary fibrosis secondary to ARDS and finally died.

Discussion

In this time of uncertainty about the management and prognosis of critically ill patients due to COVID-19 we aimed to present our experience. Thirteen per cent of COVID-19 patients admitted to hospital had to be treated in CCU. ARDS due to COVUD-19 could be analysed in 44 patients from MCCU, 77.2% of these patients undergo invasive mechanical ventilation and 23.5% of them finally died.

SARS-CoV-2 directed treatment and immunomodulation was administered to our patients attending to incoming data from literature and in vitro results.21 However, as previously reported by other authors, IL6, CRP and PCT figures were not as high as described in other circumstances such as septic shock, severe pancreatitis or burn patients.22, 23, 24, 25 Even more, the most remarkable finding was the low lymphopenia present in most of the patients. High dose steroids (1 mg/Kg) and tocilizumab were administered to the majority of the patients, and nowadays several critical voices are rising against the use of treatments lacking any medical evidence of efficacy and that entail potential harmful.26 In fact, nosocomial infections, mainly ventilator-associated pneumonia, were three times more common in COVID-19 patients than previously registered in our MCCU. Only Yang et al reported data concerning nosocomial infections in CCU patients, describing a prevalence of 22% among their patients.4

Most patients admitted to CCU needed intubation and mechanical ventilation (77%) and this seems to be in agreement with published series from Italy and USA (88%, 71% and 75% respectively).8, 9, 11 Heterogeneous and even lower percentages (from 71% to 30%) were reported by researchers from China,4, 5, 6 but in at least one of the published series a deficit in the number of CCU beds and ventilators was admitted, affecting more than 50% of potential patients.7

Mortality rate among COVID-19 ARDS ventilated patients is one of the most disheartening published results. Chinese mortality among critically ill patients was reported from 67 to 97% of ventilated patients.4, 5 Mortality from 320 ventilated patients in New York was informed to be 88%.9 Unfinished information from Italy (58% of critically ill patients remained in CCU at study publication) related a mortality of 26%, however as mortality among COVID-19 ventilated patients seems to be late (17 days [12-24] after mechanical ventilation onset in our series) we should beware of possible changes.11 The lower mortality (23.5%) observed in our series could be explained by some aspects. First, by means of the implementation of a contingency plan, CCU beds and mechanical ventilation were available for all candidates. Second, our RRS was able to early detect patients at risk (closely working with emergency specialists, internists, and pulmonologists) and patients were admitted to MCCU after a median of 2 [0-4] days in hospital. Third, in agreement with some experts recommendations,27 no delay for intubation and mechanical ventilation was admissible when excessive respiratory work appeared, patients were intubated after a median of 2 days [1-2] in MCCU. And finally, 97% of our ventilated patients needed ventilation in the prone position. The closest percentage of ventilation in the prone position for ARDS COVID19 patients comes from the publication from Martín-Loeches et al, with a rate of 79% in 29 ventilated patients and a final mortality rate of 15% (5 deaths in 39 patients, 29 under mechanical ventilation).28 However, data from Italy indicate a use of the prone position in only 27% of patients.11 The use of this manoeuvre was even lower in China (11.5% of patients) and Richardson et al do not report data regarding the use of this ventilator intervention. In line with the results from clinical trials 29we do believe in the beneficial effects that these manoeuvres have in the ARDS COVID-19 patient.

Our study has several limitations. This is a relatively small series of COVID-19 patients coming from a single hospital. Nevertheless, most published data comes from countries with very different health systems from ours and most published series remain unfinished in patient follow-up, and therefore we decided to present and share our results. The effect on the incidence of nosocomial infection and the potential relationship with immunosuppressive treatment will require larger studies or at least a comparison with similar patients in terms of mechanical ventilation duration and presence of ARDS.

In conclusion, COVID-19 ARDS patient management has been challenging for critical care specialists. All technological and knowledge resources have been required but finally mortality rate has not been as high as described in other publications. Finally, we would like to share our doubts about the relevance of the immunosuppressive treatment in this infectious disease and about its potential implication in the observed higher incidence of nosocomial infection.

Authors contributions

Dr Ramírez had full access to all of the data in the study and takes responsibility for the integrity of the data and the accuracy of the data analysis. Drs Grasselli and Zangrillo equally contributed to this work.

Concept and design: Ramírez, Gordón, Martín-Cerezulea, Castellanos

Acquisition, analysis, or interpretation of data: Ramírez, Gordón, Martín-Cerezulea, Villarreal, Padrós, Sancho, Molina, Leiva, Gimeno

Drafting of the manuscript: Ramírez, Gordón

Critical revision of the manuscript: Ramirez, Castellanos

Statistical analysis: Gordón, Martín-Cerezuela.

Funding/Support

No funding to be declare

Conflict of interest disclosure

No disclosures regarding this publication from any author

Acknowledgements

We will like to thank all staff from our MCCU who have made a valiant effort to do everything possible in the care of our patients from a health and human perspective. We would also like to thank the efforts of the services involved in the care of COVID-19 patients, especially the staff of the Microbiology and Clinical Analysis Departments.

References

- 1.WHO. Coronavirus disease. World Heal Organ [Internet]. 2020; 2019(March):2633. Available from: https://www.who.int/emergencies/diseases/novel-coronavirus-2019.

- 2.Covid- I. Informe sobre la situación de COVID-19 en España. 2020;1-15. Available from: https://www.mscbs.gob.es/profesionales/saludPublica/ccayes/alertasActual/nCov-China/situacionActual.htm.

- 3.Ballesteros Sanz MÁ, Hernández-Tejedor A., Estella Á., et al. Recommendations of the Working Groups from the Spanish Society of Intensive and Critical Care Medicine and Coronary Units (SEMICYUC) for the management of adult critically ill patients in the coronavirus disease (COVID-19) [published online ahead of print, 2020 Apr 8] Med Intensiva. 2020;S0210–5691 doi: 10.1016/j.medin.2020.04.001. 30098-X. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Yang X., Yu Y., Xu J., Shu H., Xia J., Liu H., et al. Clinical course and outcomes of critically ill patients with SARS-CoV-2 pneumonia in Wuhan China: a single-centered, retrospective, observational study. Lancet Respir Med. 2020;2600:1–7. doi: 10.1016/S2213-2600(20)30079-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Wang D., Hu B., Hu C., Zhu F., Liu X., Zhang J., et al. Clinical Characteristics of 138 Hospitalized Patients with 2019 Novel Coronavirus-Infected Pneumonia in Wuhan China. JAMA - J Am Med Assoc. 2020;323:1061–1069. doi: 10.1001/jama.2020.1585. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Huang C., Wang Y., Li X., Ren L., Zhao J., Hu Y., et al. Clinical features of patients infected with 2019 novel coronavirus in Wuhan. China. Lancet. 2020;395(10223):497–506. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(20)30183-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Du R.H., Liu L.M., Yin W., Wang W., Guan L.L., Yuan M.L., et al. Hospitalization and Critical Care of 109 Decedents with COVID-19 Pneumonia in Wuhan. China. Ann Am Thorac Soc. 2020:1–30. doi: 10.1513/AnnalsATS.202003-225OC. 0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bhatraju P.K., Ghassemieh B.J., Nichols M., Kim R., Jerome K.R., Nalla A.K., et al. Covid-19 in Critically Ill Patients in the Seattle Region - Case Series. N Engl J Med. 2020:1–11. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa2004500. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Richardson S., Hirsch J.S., Narasimhan M., Crawford J.M., McGinn T., Davidson K.W., et al. Presenting Characteristics Comorbidities, and Outcomes Among 5700 Patients Hospitalized With COVID-19 in the New York City Area. Jama [Internet]. 2020;10022:1–8. doi: 10.1001/jama.2020.6775. Available from: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/32320003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Bin S.Y., Heo J.Y., Song M.S., Lee J., Kim E.H., Park S.J., et al. Environmental Contamination and Viral Shedding in MERS Patients during MERS-CoV Outbreak in South Korea. JAMA - J Am Med Assoc Am Med Assoc. 2020;323:1612–1614. doi: 10.1093/cid/civ1020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Grasselli G., Zangrillo A., Zanella A., Antonelli M., Cabrini L., Castelli A., et al. Baseline Characteristics and Outcomes of 1591 Patients Infected with SARS-CoV-2 Admitted to ICUs of the Lombardy Region Italy. JAMA - J Am Med Assoc. 2020:1–8. doi: 10.1001/jama.2020.5394. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Jäderling G., Bell M., Martling C.R., Ekbom A., Bottai M., Konrad D. ICU admittance by a rapid response team versus conventional admittance, characteristics, and outcome. Crit Care Med. 2013;41:725–731. doi: 10.1097/CCM.0b013e3182711b94. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Mandell L.A., Wunderink R.G., Anzueto A., Bartlett J.G., Campbell G.D., Dean N.C., et al. Infectious Diseases Society of America/American Thoracic Society Consensus Guidelines on the Management of Community-Acquired Pneumonia in Adults. Clin Infect Dis. 2007;44(Supplement_2):S27–S72. doi: 10.1086/511159. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.World Health Organization. WHO Clinical management of severe acute respiratory infection (SARI) when COVID-19 disease is suspected. Who [Internet]. 2020;(March):12. Available from: https://www.who.int/internal-publications-detail/clinical-management-of-severe-acute-respiratory-infection-when-novel-coronavirus-(ncov)-infection-is-suspected%0Ahttp://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/10665/178529/1/WHO_MERS_Clinical_15.1_eng.pdf.

- 15.Ruiz J., Ramirez P., Gordon M., Villarreal E., Frasquet J., Poveda-Andres J.L., et al. Antimicrobial stewardship programme in critical care medicine: A prospective interventional study. Med Intensiva. 2018;42:266–273. doi: 10.1016/j.medin.2017.07.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Fan E., Del Sorbo L., Goligher E.C., Hodgson C.L., Munshi L., Walkey A.J., et al. An official American Thoracic Society/European Society of intensive care medicine/society of critical care medicine clinical practice guideline: Mechanical ventilation in adult patients with acute respiratory distress syndrome. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2017;195:1253–1263. doi: 10.1164/rccm.201703-0548ST. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Horan T.C., Andrus M., Dudeck M.A. CDC/NHSN surveillance definition of health care-associated infection and criteria for specific types of infections in the acute care setting. Am J Infect Control. 2008;36:309–332. doi: 10.1016/j.ajic.2008.03.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Blot S.I., Taccone F.S., Van Den Abeele A.M., Bulpa P., Meersseman W., Brusselaers N., et al. A Clinical Algorithm to Diagnose Invasive Pulmonary Aspergillosis in Critically Ill Patients. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2012;186:56–64. doi: 10.1164/rccm.201111-1978OC. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kalil A.C., Florescu D.F. Prevalence and mortality associated with cytomegalovirus infection in nonimmunosuppressed patients in the intensive care unit. Crit Care Med. 2009;37:2350–2358. doi: 10.1097/CCM.0b013e3181a3aa43. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Luyt C.E., Combes A., Deback C., Aubriot-Lorton M.H., Nieszkowska A., Trouillet J.L., et al. Herpes simplex virus lung infection in patients undergoing prolonged mechanical ventilation. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2007;175:935–942. doi: 10.1164/rccm.200609-1322OC. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Alhazzani W., Møller M.H., Arabi Y.M., Loeb M., Gong M.N., Fan E., et al. Surviving Sepsis Campaign: guidelines on the management of critically ill adults with Coronavirus Disease 2019 (COVID-19) [Internet] Intensive Care Medicine. Springer Berlin Heidelberg; 2020 doi: 10.1007/s00134-020-06022-5. Available from: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00134-020-06022-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Ramirez P., Villarreal E., Gordon M., Gómez M.D., De Hevia L., Vacacela K., et al. Septic Participation in Cardiogenic Shock: Exposure to Bacterial Endotoxin. Shock. 2017;47:588–592. doi: 10.1097/SHK.0000000000000798. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Takahashi W., Nakada T., Yazaki M., Oda S. Interleukin-6 levels act as a diagnostic marker for infection and a prognostic marker in patients with organ dysfunction in intensive care units. Shock. 2016 Sep;46:254–260. doi: 10.1097/SHK.0000000000000616. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Chen T., Wu D., Chen H., Yan W., Yang D., Chen G., et al. Clinical characteristics of 113 deceased patients with coronavirus disease 2019: Retrospective study. BMJ. 2020:368. doi: 10.1136/bmj.m1091. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Wu C., Chen X., Cai Y., Xia J., Zhou X., Xu S., et al. Risk Factors Associated with Acute Respiratory Distress Syndrome and Death in Patients with Coronavirus Disease 2019 Pneumonia in Wuhan. China. JAMA Intern Med. 2020:1–10. doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2020.0994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Zagury-Orly I., Schwartzstein R.M. Covid-19 - A Reminder to Reason. N Engl J Med. 2020 Apr 28 doi: 10.1056/NEJMp2009405. [Epub ahead of print] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Marini J.J., Gattinoni L. Management of COVID-19 respiratory distress. JAMA. 2020 Apr 24 doi: 10.1001/jama.2020.6825. [Epub ahead of print] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Blake A., Collins D., O’Connor E., Bergin C., McLaughlin A.M., Martin-Loeches I. Clinical and biochemical characteristics of patients admitted to ICU with SARS-CoV-2 [published online ahead of print, 2020 May 16] Med Intensiva. 2020 doi: 10.1016/j.medin.2020.05.003. 10.1016/j.medin.2020.05.003. doi:10.1016/j.medin.2020.05.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Guérin C., Reignier J., Richard J.C., Beuret P., Gacouin A., Boulain T., et al. Prone positioning in severe acute respiratory distress syndrome. N Engl J Med. 2013;368:2159–2168. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1214103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]