Abstract

SARS-CoV-2, the virus responsible for novel Coronavirus (COVID-19) infection, has recently been associated with a myriad of hematologic derangements; in particular, an unusually high incidence of venous thromboembolism has been reported in patients with COVID-19 infection. It is postulated that either the cytokine storm induced by the viral infection or endothelial damage caused by viral binding to the ACE-2 receptor may activate a cascade leading to a hypercoaguable state. Although pulmonary embolism and deep venous thrombosis have been well described in patients with COVID-19 infection, there is a paucity of literature on cerebral venous sinus thrombosis (cVST) associated with COVID-19 infection. cVST is an uncommon etiology of stroke and has a higher occurrence in women and young people. We report a series of three patients at our institution with confirmed COVID-19 infection and venous sinus thrombosis, two of whom were male and one female. These cases fall outside the typical demographic of patients with cVST, potentially attributable to COVID-19 induced hypercoaguability. This illustrates the importance of maintaining a high index of suspicion for cVST in patients with COVID-19 infection, particularly those with unexplained cerebral hemorrhage, or infarcts with an atypical pattern for arterial occlusive disease.

Key Words: COVID-19, Coronavirus, Hypercoaguability, Venous sinus thrombosis, Venous thromboembolism, Stroke

Introduction

Hematologic effects of SARS-CoV-2 infection have been increasingly recognized and documented in recent literature. An atypically high incidence of venous thromboembolism (VTE) has been reported ranging from 7.7 to 28.0% in patients hospitalized with COVID-19 associated pneumonia even with appropriate VTE prophylaxis.1 , 2 Previous studies have demonstrated that COVID-19 infection is associated with an increase in prothrombotic markers such as fibrinogen and D-dimer, as well as inflammatory markers such as C-reactive protein and interleukin-6,3 which are associated with a hypercoaguable state. Similarly, ischemic stroke, in particular, cryptogenic stroke, has been reported in patients with COVID-19.4 More recently, cases of cerebral venous sinus thrombosis have been reported in patients with COVID-19 infection.5, 6, 7, 8

Cerebral venous sinus thrombosis (cVST) is an uncommon subtype of stroke with an annual incidence of 2–5 cases per million people. Unique to this subtype of stroke is a predilection for younger patients, particularly women. Headache is the most common presenting symptom, followed by seizures, then focal neurologic deficits.9 In many cases, a risk factor such as an inherited coagulopathy, an antecedent history of trauma, cancer, or hormonal contraception can be identified. Recently, SARS-CoV-2 has been postulated as a risk factor for cVST by inducing a hypercoaguable state. Interestingly, although data is limited, there appears to be a roughly equal incidence in males and females with COVID-19-associated cVST. We report on three cases of cVST associated with COVID-19 admitted to our hospital, as well as a review the other cases reported in recent literature.

Case report

We report on three separate cases of dural venous sinus thrombosis occurring in patients with SARS-CoV-2 infection at our institution.

Patient 1

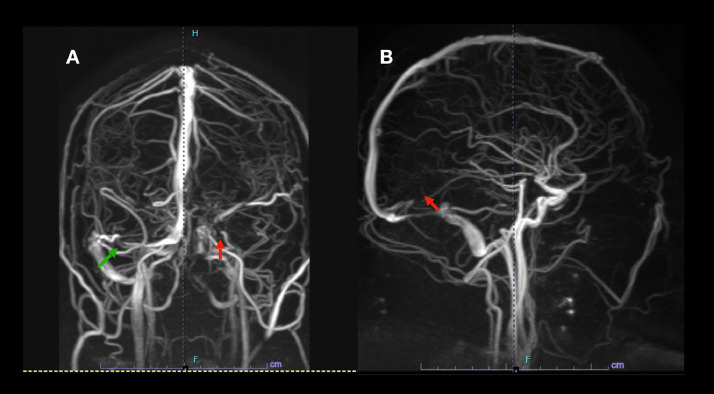

A 17 year old boy with a history of obesity who had tested positive for SARS-COV-2 two weeks prior to admission presented with two weeks of new-onset left-sided headaches, worst upon awakening in the morning, and with occasional emesis. He had been diagnosed with COVID-19 infection on a prior medical visit for new-onset hypertension and headaches, and had not endorsed cough or any respiratory symptoms. Additionally, he noted blurred vision. On admission, he was alert and oriented with no focal neurologic deficits on exam. Blood pressure on presentation was 138/88 mmHg. Fundoscopic exam revealed papilledema. MRI brain with MR venography revealed extensive dural venous sinus thrombosis involving the straight sinus, torcula, left transverse and sigmoid sinus, extending into the jugular vein, as well as right transverse sinus, superior sagittal sinus and left vein of Labbe (Fig. 1 ). He had no family history of thrombotic disease and did not take any prothrombotic medications. He was started on therapeutic anticoagulation with enoxaparin and admitted to the pediatric intensive care unit. Admission labs were significant for elevated D-dimer of 1.13 and otherwise normal coagulation parameters (see Table 1 ). A thorough hypercoaguability workup including homocysteine, anticardiolipin antibodies, antithrombin III, protein C, protein S, prothrombin gene mutation, Factor V Leiden genetic mutation, and beta-2-glycoprotein were unremarkable. As anticipated with an acute thrombotic event, Lipoprotein A was markedly elevated at 125.40 nmol/L, and Factor VIII activity was elevated at 261%. His neurologic status remained stable throughout his hospital course. He was discharged home on anticoagulation on hospital day 10. He presented again to the hospital two weeks later, with transient visual disturbances, which were attributed to persistent elevation in intracranial pressure. Repeat neuroimaging revealed improving clot burden. He was managed conservatively with observation and discharged shortly thereafter.

Fig. 1.

(A) Magnetic resonance venography (MRV) demonstrates occlusion of the left transverse sinus (red arrow) and no opacification of the sigmoid sinus and jugular vein as well as occlusion of a segment of the right transverse sinus (green arrow). (B) Demonstrates occlusion of the straight sinus (green arrow). (For interpretation of the references to color in this figure legend, the reader is referred to the web version of this article.)

Table 1.

Clinical and radiologic features of cases with COVID-19 and cVST.

| Variable | Patient 1 | Patient 2 | Patient 3 | Garaci et al | Poillon et al (1) | Poillon et al (2) | Hughes et al | Klein et al | Hemasian and Ansari | Dahl-Cruz et al |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age | 17 | 72 | 26 | 44 | 62 | 54 | 59 | 29 | 65 | 53 |

| Sex | M | F | M | F | F | F | M | F | M | M |

| Medical Comorbidities | Obesity | Breast cancer in remission | None | None | Morbid obesity | Breast cancer in remission with hormone therapy | Type II diabetes, hypertension | None | None | Former smoker |

| Onset of COVID symptoms to VST symptoms | About the same time | 3 days | 2 weeks | 2 weeks | 15 days | 2 weeks | Same time | 1 week | Same day | 1 week |

| NIHSS* | 0 | 1 | 6 | NR | NR | NR | 10 | NR | NR | 3 |

| Presenting Symptoms⁎⁎ | Headache, blurry vision | Dysarthria, left hand weakness as well as dyspnea | Left arm and leg severe hemiparesis and mild sensory loss | Encephalopathy, right sided weakness and aphasia as well as worsening dyspnea | Encephalopathy, right sided weakness, and headaches | Severe headache | Severe headache initially; then right sided weakness, dysarthria, aphasia | New-onset seizures and one week of headaches and viral symptoms | New-onset seizure | Focal seizures of the right arm; sensory loss and mild right arm weakness and ataxia |

| COVID diagnosis | SARS-CoV-2 swab positive two weeks prior to presentation; SARS-CoV-2 IgG antibody positive confirmed on admission | Bilateral ground-glass opacities on CT as well as chest x-ray; thrombocytopenia, lymphopenia and increased inflammatory markers and hypoxic respiratory failure consistent with clinical diagnosis. | SARS-CoV-2 swab positive two weeks prior to presentation; repeat SARS-CoV-2 PCR was positive on admission | SARS-CoV-2 swab positive on admission | SARS-CoV-2 swab positive on admission | CT chest revealing typical bilateral ground glass opacities; clinical symptoms suggestive of COVID-19. | SARS-CoV-2 swab positive on admission | SARS-CoV-2 swab positive on admission | SARS-CoV-2 swab positive on admission | SARS-CoV-2 swab positive within 24 h of admission |

| WBC (4.8-10.8 k/mm3) | 9.4 | 4.2 | 5.2 | 9.6 | 20.22 | 18.32 | 7.6 | 8.76 | NR | Elevated (NR) |

| PT (9.8-12.0) sec | 11.3 | 11.7 | 11.2 | NR | NR | NR | 11.1 | 12.7 | NR | Normal (NR) |

| aPTT | 25.7 | 33.5 | 26.5 | NR | NR | NR | 22.3 | 28.7 | NR | Normal (NR) |

| INR | 1.06 | 1.10 | 1.05 | NR | NR | NR | NR | 1.1 | NR | Normal (NR) |

| Fibrinogen (mg/dL) (180-400) | 355 | 509 | 312 | NR | NR | NR | 3.9 g/L (nl 2.0-4.0) | NR | NR | NR |

| MRI Findings | Dural venous sinus thrombosis in the left transverse and sigmoid sinuses extending to the left internal jugular din and straight sinus; possible thrombus within the left vein of Labbe. No evidence of hemorrhage or venous infarct. | NP | MRI with hemorrhage in the right parasagittal region | NR | Left fronto-temporal hemorrhage | Large left temporal lobe hemorrhage | NR | Left temporoparietal hemorrahge with mass effect and effacement of ventricle | Right temporal hemorrhage | NR |

| CTV/MRV findings | MRV; elongated filling defect from confluence of sinuses, left transverse and sigmoid sinuses, proximal internal jugular vein. Additional partial extension into right transverse and superior sagittal sinus. Large thrombus in straight sinus as well as left vein of Labbe. | CTV; Right sigmoid sinus and jugular bulb filling defects. | MRV with no evidence of dural venous sinus thrombosis.⁎⁎⁎ | CTA/V showed filling defects in the vein of Galen, straight sinus, and the torcula as well as the left internal cerebral vein | CTV; filling defects in left transverse sinus, straight sinus, vein of Galen, internal cerebral veins | CTV and MRA; left transverse sinus thrombosis | Right sigmoid sinus, transverse sinus, and torcula | MRV; left transverse, sigmoid sinus and jugular vein thrombosis | MRV; right sigmoid and transverse sinus thrombosis | CTV; right transverse sinus and superior sagittal sinus filling defect |

| Treatment | Enoxaparin | Not anticoagulated due to change in goals of care | Not anti coagulated due to size of hemorrhage, ambiguity of findings | Toculizumab, Nadroparin | NR | NR | Low molecular weight heparin initially, then transitioned to apixaban | Enoxaparin and anti epileptics | Anticoagulation and anti epileptics | Low molecular weight heparin and anti epileptics |

| Outcome | Discharged to home; readmitted two weeks later with scotomas, stable neuroimaging | Due to critically ill state and prior expressed wishes, patient transitioned to comfort care, died in hospital. | Patient's left sided weakness improved while he was in the hospital but still persistently paretic; discharged to acute rehab | Not reported | Not reported | Not reported | Improvement in NIHSS from 10 to 4, discharge to home | Neurologic symptoms improved, moderate mixed aphasia and persistent bilateral CN VI palsies present | Discharged home 10 days later in good health | Clinical stability; discharged home after 10 days |

on presentation.

including seizure, headache, focal neurologic deficit, altered mental status.

diagnostic cerebral angiography revealed a possible filling defect at the junction of Trolard with the inferior sagittal sinus.

Patient 2

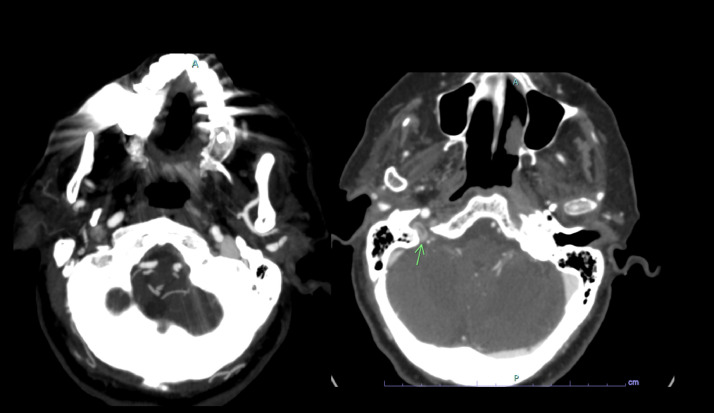

A 72 year old woman with a remote history of breast cancer in remission and not on hormonal therapy presented to the hospital with two days of dyspnea and generalized weakness. Vital signs on admission included BP 113/78 mmHg, pulse of 93, respiratory rate of 16, and normal body temperature. Admission labs were notable for a mildly elevated C-reactive protein at 2.80 mg/dL. A respiratory viral panel was sent and negative. Initial chest X-ray demonstrated a consolidation in the left lower lobe. The patient was admitted to the medical service and treated with azithromycin for presumed community acquired pneumonia. A SARS-CoV-2 rt-PCR test sent on admission returned positive suggestive of COVID-19 infection. The patient's respiratory status worsened throughout admission, and on hospital day 5 they were transferred to the COVID medical intensive care unit due to increasing oxygen requirements eventually requiring intubation. Additionally, the patient developed a thrombocytopenia with platelets dropping from 187,000 on admission to a nadir of 68,000. The patient was noted to have worsening dysarthria and a subtle left-handed weakness, prompting neurology consultation. A CT angiogram demonstrated a filling defect in the right transverse sinus and jugular bulb suggestive of venous sinus thrombosis (Fig. 2 ). We hypothesized that venous infarction was likely responsible for the patient's symptoms. Due to the patient's precipitously worsening condition, the family wished to transition her to comfort measures and ultimately died on hospital day six.

Fig. 2.

CT angiogram with delayed phase shows filling defect in the right sigmoid sinus and jugular bulb (green arrow). (For interpretation of the references to color in this figure legend, the reader is referred to the web version of this article.)

Patient 3

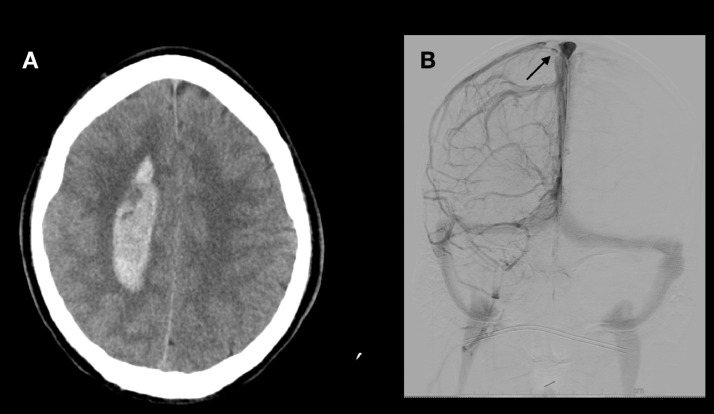

A 26 year old man with no past medical history other than recent SARS-CoV-2 infection was playing basketball with friends when he developed sudden-onset left sided hemiparesis followed by severe headache, nausea, and dizziness. A CT scan demonstrated a right parasagittal intracerebral hemorrhage. On admission, blood pressure was normotensive and other vital signs were unremarkable. SARS-CoV-2 rt-PCR collected on admission was positive. A few weeks prior, he had developed a mild viral syndrome and was diagnosed with COVID-19 infection, of which the symptoms had resolved. Coagulation parameters and platelet count were unremarkable. Exam was notable for left-sided hemiparesis (4/5 motor strength) with hemisensory loss. CT angiogram demonstrated prominent vessels in the right hemisphere suspicious for an arteriovenous malformation. MR venogram did not show any dural venous thrombosis, and MRI did not demonstrate a clear cortical vein thrombosis. A diagnostic cerebral angiogram was performed the next morning, which showed a developmental venous anomaly. Additionally, there was a filling defect of the right junction of the vein of Trolard with the superior sagittal sinus (Fig. 3 ). We suspected that venous hypertension was likely the underlying etiology of the hemorrhage. Given the ambiguity of the findings and the presence of a sizable hemorrhage, anticoagulation was deferred and he was discharged with short-interval follow-up imaging. The patient's neurologic exam remained stable to improving at time of discharge, with some residual left-sided weakness. Subsequent repeat angiogram performed several weeks after discharge supported the diagnosis of cortical vein thrombosis, demonstrating a persistent filling defect with substantial improvement in venous drainage, and did not demonstrate any evidence of arteriovenous fistula or malformation.

Fig. 3.

(A) Noncontrast CT brain demonstrates the right parasagittal hemorrhage; (B) diagnostic cerebral angiography, right internal carotid injection, coronal view, venous phase showing filling defect in the right junction of Trolard with superior sagittal sinus (black arrow).

Discussion

These cases of COVID-19 associated cVST add to the current and growing body of literature on cVST as a potential thromboembolic complication of COVID-19.

Of note, in one of our cases and in several of the reported cases in the literature, the COVID-19 infection preceded the symptoms of venous sinus thrombosis by up to two weeks. This suggests that the hypercoaguable effect of COVID-19 infection may possibly persist relative to the initial infectious event. There are many mechanisms by which SARS-CoV-2 has been postulated to enhance coagulation. First, it is known that D-dimer, fibrinogen, and fibrin degradation products are elevated relative to healthy controls. Additionally, the SARS-CoV-2 interaction with the ACE receptor may result in endothelial injury thereby promoting a hypercoagulable state.10 A report of pulmonary embolism associated with COVID-19 appears to support this notion; as the authors suggest that cytokine storm, most prominent in the second week after symptom onset, may be associated with the hightened risk of VTE associated with the SARS-CoV-2 infection.11

Cerebral venous thrombosis has been reported to occur in the presence of other thrombotic phenomena. For example, one report described a woman with a pulmonary embolism and superior vena cava occlusion in conjunction with dural venous sinus thrombosis.5 In other cases, isolated cerebral venous sinus thrombosis occurred in the presence of moderate or severe COVID-19 infection6; however, in our series, two patients experienced a relatively mild viral illness, suggesting that patients without severe respiratory or systemic symptoms may still suffer from comorbidities associated with viral hypercoaguability. It is possible in some of these patients that there may be a predisposing risk factor for venous sinus thrombosis, such as one reported case in which severe iron deficiency anemia was discovered in a young woman with COVID-19 and venous sinus thrombosis.12

Additionally, as headache can be a common symptom of viral illnesses including COVID-19, diagnosis can often be elusive or delayed until symptoms worsen.7 This effect may be compounded by the observation that COVID-19 associated cVST, in comparison to cVST of other etiologies, has less of a female predominance and can occur in patients with relatively mild or asymptomatic COVID-19. For this reason, patient's viral illness sometimes goes unacknowledged, and their COVID-19 status may not be established until presenting with symptoms related to COVID-associated neurologic conditions.12 , 8

Conclusion

SARS-CoV-2 infection has been associated with a hypercoaguable state, characterized by elevated D-dimer and fibrinogen levels, and a high incidence of venous thromboembolism including pulmonary embolism and deep venous thrombosis. While venous sinus thrombosis is an uncommon etiology of stroke, our series as well as recent reports suggest that there may be an association between SARS-CoV-2 infection and the development of cerebral venous sinus thrombosis. Given that symptoms such as headache may be insidious and nonspecific, it is imperative for clinicians to consider venography in patients with COVID-19 infection who present with atypical infarct or hemorrhage patterns or unexplained elevations in intracranial pressure.

Acknowledgments

Grant support

None.

Footnotes

Work performed at Westchester Medical Center at New York Medical College, Valhalla, New York; Department of Neurosurgery.

References

- 1.Maatman TK, Jalali F, Feizpour C, Douglas A, 2nd, McGuire SP, Kinnaman G. Routine venous thromboembolism prophylaxis may be inadequate in the hypercoagulable state of severe coronavirus disease 2019. Crit Care Med. 2020 doi: 10.1097/CCM.0000000000004466. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Lodigiani C, Iapichino G, Carenzo L, Cecconi M, Ferrazzi P, Sebastian T. Venous and arterial thromboembolic complications in COVID-19 patients admitted to an academic hospital in Milan, Italy. Thromb Res. 2020;191:9–14. doi: 10.1016/j.thromres.2020.04.024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bikdeli B, Madhavan MV, Jimenez D, Chuich T, Dreyfus I, Driggin E. COVID-19 and thrombotic or thromboembolic disease: implications for prevention, antithrombotic therapy, and follow-up. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2020 doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2020.04.031. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Yaghi S, Ishida K, Torres J, Mac Grory B, Raz E, Humbert K. SARS2-CoV-2 and stroke in a new york healthcare system. Stroke. 2020;51:2002–2011. doi: 10.1161/STROKEAHA.120.030335. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Garaci F, Di Giuliano F, Picchi E, Da Ros V, Floris R. Venous cerebral thrombosis in COVID-19 patient. J Neurol Sci. 2020;414 doi: 10.1016/j.jns.2020.116871. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Poillon G, Obadia M, Perrin M, Savatovsky J, Lecler A. cerebral venous thrombosis associated with COVID-19 infection: causality or coincidence? J Neuroradiol. 2020 doi: 10.1016/j.neurad.2020.05.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hughes C, Nichols T, Pike M, Subbe C, Elghenzai S. Cerebral venous sinus thrombosis as a presentation of COVID-19. Eur J Case Rep Intern Med. 2020;7 doi: 10.12890/2020_001691. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hemasian H, Ansari B. First case of COVID-19 presented with cerebral venous thrombosis: a rare and dreaded case. Rev Neurol. 2020;176:521–523. doi: 10.1016/j.neurol.2020.04.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Capecchi M, Abbattista M, Martinelli I. Cerebral venous sinus thrombosis. J Thromb Haemost. 2018;16:1918–1931. doi: 10.1111/jth.14210. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Khan IH, Savarimuthu S, Tsun Leung MS, Harky A. The need to manage the risk of thromboembolism in COVID-19 patients. J Vasc Surg. 2020;5 doi: 10.1016/j.jvs.2020.05.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Griffin DO, Jensen A, Khan M, Chin J, Chin K, Saad J. Pulmonary embolism and increased levels of d-dimer in patients with coronavirus disease. Emerg Infect Dis. 2020:26. doi: 10.3201/eid2608.201477. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Klein DE, Libman R, Kirsch C, Arora R. Cerebral venous thrombosis: atypical presentation of COVID-19 in the young. J Stroke Cerebrovasc Dis. 2020 doi: 10.1016/j.jstrokecerebrovasdis.2020.104989. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]