Abstract

Background

COVID-19 caused by a novel coronavirus, a severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus type 2 (SARS-CoV-2), has recently broken out worldwide. Up to now, the development of vaccine is still in the stage of clinical research, and there is no clinically approved specific antiviral drug for human coronavirus infection. The purpose of this study is to investigate the key molecules involved in response during SARS-CoV-2 infection and provide references for the treatment of SARS-CoV-2.

Methods

We conducted in-depth and comprehensive bioinformatics analysis of human proteins identified with SARS-CoV-2, including functional enrichment analysis, protein interaction network analysis, screening of hub genes, and evaluation of their potential as therapeutic targets. In addition, we used the gene-drug database to search for inhibitors of related biological targets.

Results

Several significant pathways, such as PKA, centrosome and transcriptional regulation, may greatly contribute to the development and progression of COVID-2019 disease. Taken together 15 drugs and 18 herb ingredients were screened as potential drugs for viral treatment. Specially, the trans-resveratrol can significantly reduce the expression of N protein of MERS-CoV and inhibit MERS-CoV. In addition, trans-resveratrol, Epigallocatechin-3-gallate (EGCG) and BX795 all show good anti multiple virus effects.

Conclusion

Some drugs selected through our methods have been proven to have antiviral effects in previous studies. We aim to use global bioinformatics analysis to provide insights to assist in the design of new drugs and provide new choices for clinical treatment.

Key Words: 2019-nCoV coronavirus, Bioinformatics, Integrated analysis, SARS-CoV-2, Mechanism, Drug

Introduction

Coronavirus (CoV) belongs to the subfamily Orthocoronavirinae of Coronaviridae and is considered to cause only mild respiratory diseases in human. However, severe respiratory syndrome caused by SARS-CoV virus broke out worldwide in 2003, with a fatality rate of up to 10%, and even as high as 50% among people over the age of 60. The fatality rate of Middle East respiratory syndrome caused by MERS coronavirus in 2012 is as high as 40% (1,2). And other coronavirus infections have been found after the outbreak of SARS-CoV virus such as NL63 and HKU1, and people gradually have a new understanding of coronavirus (3). At present, there is no therapeutic agent for human coronavirus in clinic (4). In the face of SARS-CoV and MERS-CoV which has recently spread all over the world, people can only take measures such as the isolation and restriction of entry and exit (5, 6, 7). And even it is only supportive treatment for critically ill patients. All these situations show that it is necessary to consider the treatment of severe coronavirus infection.

Recently, an ongoing outbreak of the epidemic caused by a novel β-coronavirus known as severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2 or COVID-2019), has been declared a global public health emergency of international concern by the World Health Organization (WHO). It has rapidly spread across China and rest of the world. Moreover, SARS-CoV-2 has higher rate of infection and more deaths have been caused in contrast to SARS and MERS. So far, data from WHO have shown that more than 3,634,172 confirmed cases and 251,446 fatalities had been recorded in 150 countries/regions, including USA, Japan and Spain (8). Hence, the rapid deployment of effective therapeutics is a high priority as there is currently no specific therapy or vaccine for SARS-CoV-2.

On behalf of the omics and cryoelectronic microscopy technologies, the first whole-genome sequence of SARS-CoV-2 was released on January 10, 2020 (9). And then, several proteins from SARS-CoV-2 genome had been resolved such as 3CL-PRO, PL-PRO and Nsp9 (10). These studies helped researchers to quickly identify potential inhibitors for SARS-CoV-2. Recently, Gordon DE, et al. expressed 26 of the 29 viral proteins in human cells and identified the human proteins physically associated with these viral proteins (11).

In the present study, we implemented an in-depth and comprehensive bioinformatics analysis of the human proteins identified with SARS-Cov-2 and evaluated their potential as therapeutic targets. Furthermore, we explored the associated important biological process, so as to provide additional data resources for future research.

Method

Selection of Gene Datasets

In the present study, the 332 human proteins (Dataset 1) identified with SARS-CoV-2-human PPIs were obtained from the research of Gordon DE, et al. (11). GEPIA database (http://gepia.cancer-pku.cn/) (12) was established using 9736 tumor and 8587 normal samples from the TCGA and GTEx projects, which include tumor and/or normal differential expression analysis, correlation analysis and gene expression similarities. In the present study, the correlation of genes with the hub genes in normal lung tissue rank top 20 were collected using the PCC (Pearson Correlation Coefficient) as Dataset 2. The hub genes in dataset 1 and dataset 2 were identified according to degree using MCODE and cytohubba modules of cytoscape software (http://www.cytoscape.org/) (13).

GO and KEGG Pathway Enrichment Analyses

The Database for Annotation Visualization and Integrated Discovery (DAVID; https://david.ncifcrf.gov/) (14,15) is an online biological tool to perform GO functional annotation and Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes (KEGG) pathway analysis. The GO functional analysis included the cellular component (CC), biological process (BP), and molecular function (MF) categories (16). And KEGG pathway enrichment analysis (17) was performed to further illuminate the potential functions. Results with p-value <0.05 and gene counts ≥2 were considered statistically significant.

Protein-Protein Interaction (PPI) Network Construction and Hub Genes Identification

The Search Tool for the Retrieval of Interacting Genes (STRING) (http://string-db.org/) (18) is an online database used to predict PPIs, which are essential for interpreting the molecular mechanisms of key cellular activities in carcinogenesis. A PPI network was constructed using the STRING online database with the condition of high confidence 0.7. The PPI networks of STRING database were visualized by cytoscape software.

Drug Screening Based on Drug-Gene Interaction

DrugBank database (https://www.drugbank.ca/) (19) provides detailed biochemical indicators and target information for each drug entry in the database. It is one of the most comprehensive drug databases at present. Drug-Gene Interaction database (http://www.dgidb.org/) (20) provides two types of information: known drug-gene interactions and druggable genes that have not been targeted therapeutically. IUPHAR/BPS Guide to Pharmacology (https://www.guidetopharmacology.org/) (21) is a database of ligand-activity-target relationships, mostly from high-quality pharmacology and pharmaceutical chemistry literature. Hub genes calculated from dataset 1 and dataset 2 as the targets were used to research drugs and inhibitors of hub genes were merged from the three databases. The molecules approved by FDA and clinical candidates or pre-clinical research molecules with good targeting are given priority. The retrieval data of Chinese herbal ingredients are derived from the traditional Chinese medicine gene database TCMID (http://tcm.lifescience.ntu.edu.tw/) (22) using core genes to screen related Chinese herbal medicine components. According to the five principles of drugs (23), PubChem (https://pubchem.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/) (24) was used to perform further structural screening of Chinese herbal medicine ingredients obtained from the TCMID database so as to obtain more reliable active ingredients.

Results

Functional Enrichment

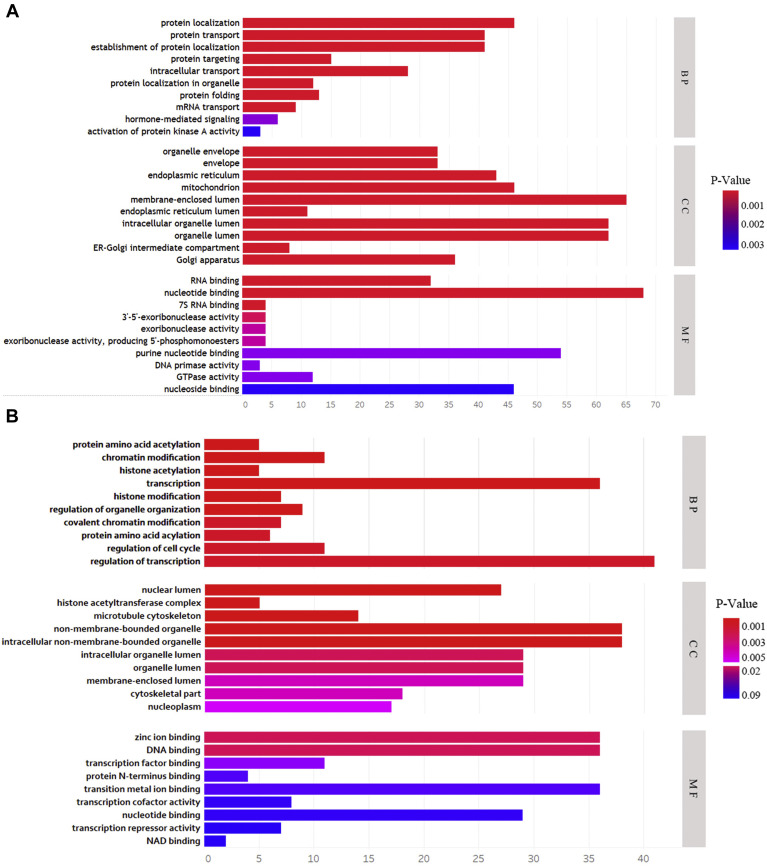

The functional enrichment analysis of dataset 1 molecules interacting with SARS-CoV-2 virus proteins was performed using DAVID database. The results revealed that protein localization, protein transport, establishment of protein localization, protein targeting and intracellular transport were the significantly enriched BP terms. Concerning the CC analysis, the human proteins were enriched in organelle envelope, envelope, endoplasmic reticulum, mitochondrion and membrane-enclosed lumen. For MF analysis, the proteins were mainly enriched in RNA binding, nucleotide binding, 7s RNA binding, 3′-5′-exoribonuclease activity and exoribonuclease activity (Figure 1 A, Supplementary Table 1). In addition, KEGG pathway analysis showed that the most significant pathways identified were Protein export, DNA replication, Glycan biosynthesis, Glycosylphosphatidylinositol-anchor biosynthesis and RNA degradation. Owing to the fact that SARS-CoV-2 virus mainly attacks the lung tissue in the body, related genes with hub genes of dataset 1 were retrieved from GEPIA database using the Pearson correlation analysis (Supplementary Table 2). Genes from dataset 2 were mainly enriched in protein amino acid acylation, chromatin modification, histone acetylation, transcription, histone modification (Figure 1B, Supplementary Table 1).

Figure 1.

(A and B) Gene Ontology analysis of dataset 1 and dataset 2 molecules based on three aspects including biological processes (BP), cellular components (CC), and molecular functions (MF).

PPI Network Construction and Hub Gene Identification

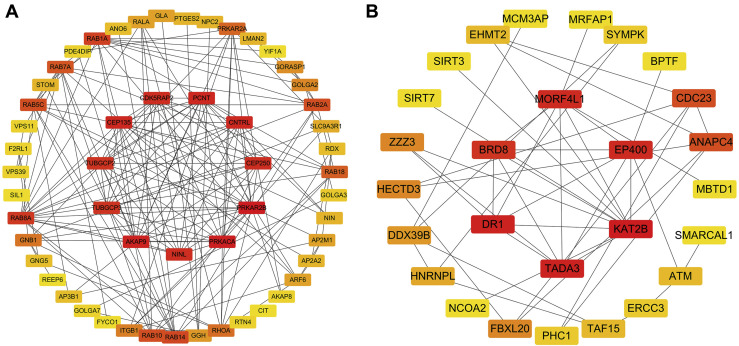

To investigate the PPIs between 332 SARS-CoV-2 interacting human proteins, the STRING database was used to identify the PPI network. It can be seen that a total of 328 nodes and 504 edges were involved in the PPI network with the help of cytoscape. The 10 most important genes showing significant interaction were PRKAR2B, PRKACA, AKAP9, PCNT, CEP135, CNTRL, CDK5RAP2, CEP250, NINL, TUBGCP2, TUBGCP3 (Figure 2 A). Except for TUBGCP2 and TUBGCP3, which was related to the M protein Nsp 13 of the virus. The function of PRKAR2B and PRKACA are enriched in hormone-mediated signaling, nucleotide binding, purine nucleotide binding and activation of protein kinase A activity. The rest of them are mainly related to Golgi apparatus, centrosome, microtubule organizing center, nucleotide binding, purine nucleotide binding. As for related gene sets in lung tissues, the six most significant genes (KAT2B, TADA3, DR1, EP400, MORF4L1, BRD8) were identified (Figure 2B). These six genes were mainly enriched in protein amino acid acylation, chromatin modification, regulation of transcription, nuclear lumen, histone acetyltransferase complex.

Figure 2.

(A and B) The protein networks of dataset 1 and dataset 2 using Cytoscape are shown. The representation is as follows: boxes represent genes and lines represent the interaction of proteins between genes. The redder the color, the more important the gene is in the network.

Drug Screening Based on Drug-Gene Interaction

Drugs targeting all the significant genes from human proteins and related gene sets were explored using the DrugBank, IUPHAR and DGIdb database. PRKAR2B, PRKACA and KAT2B were selected as the potential targets of 15 drugs (Supplementary Table 3). Meanwhile, 18 herb ingredients identified from TCMID database were associated with potential drug targets in order to have more suggestions on clinical treatment (Supplementary Table 4).

Discussion

Although the isolation and structural analysis of many kinds of coronaviruses have been completed during the virus outbreak, there is still no specific drug for SARS-CoV-2 (25). Gordon DE, et al. had identified 332 human proteins related to SARS-CoV-2 by affinity purification mass spectrometry (11). Based on this work, 332 human proteins were considered as potential drug targets in this study, and reconstructed a protein-protein interaction network with high confidence. Cytoscape software was used for PPI analysis, from which the top 10 hub genes were obtained as the first round of core targets for screening. Clinical evidence suggest that novel coronavirus mainly infects lung tissue in the human body, which leads to dyspnea and even respiratory failure (26, 27, 28). Therefore, we further searched the related genes with similar expression profiles to the hub genes in lung tissue, and selected the second round of hub genes and related drugs. A total of 14 pre-clinical molecules, 1 clinical drug and several Chinese herb ingredients were screened out. It is hoped that this series of work will provide new insights and help for the clinical treatment of SARS-CoV-2.

The latest research shows that the entry of SARS-CoV-2 into host cells also depends on SARS-CoV receptor ACE2 (29, 30, 31). At present, there are some drugs targeting human interacting proteins as clinical candidates for SARS-CoV-2, such as ACE2 inhibitors losartan and telmisartan (32,33). Wang M, et al. reported that chloroquine is also used in clinical medicine, which is a traditional drug for the treatment of malaria. And chloroquine can also interfere with the glycosylation of coronavirus receptor ACE2, which may affect the binding of virus and receptor (34). Therefore, it is necessary to inhibit the interaction between virus protein and human proteins in order to inhibit the biological effects caused by virus from the current clinical treatment scheme. Targeting these proteins to inhibit the biological effects of the virus in vivo may become a new potential drug therapy mechanism for SARS-CoV-2.

Among the hub genes screened of the first round, eight proteins were enriched in the protein subnetwork related to the viral protein Nsp13, and only two genes TUBGCP2 and TUBGCP3 were mapped to the viral M protein. Sequencing the genomes of all coronaviruses including SARS-CoV-2 showed that the sequences of structure proteins S, E, M, HE and N proteins were changed to some extent (35). This increases the difficulty to identify anti-SARS-CoV-2 inhibitors. Nsp13 helicase is a non-structural protein in SARS-CoV-2 that separates double-stranded RNA or DNA with 5′→3′ polarity in a NTP dependent manner (36). Because of its strong conservatism (37), and its function is indispensable in the life cycle of coronavirus, Nsp13 has become an ideal target for the development of anti-virus drugs (38,39). And some virus helicases have been used as proven drug targets, such as herpes simplex virus (HSV). Therefore, a great deal of effort has been spent on developing small molecular inhibitors and chemicals as candidate drugs to inhibit the function of SARS coronavirus helicase Nsp 13 (40). Bananin derivatives can inhibit the helicase activity of SARS coronavirus and the competitive inhibitor ADK developed by the metal-binding domain, which is essential for the viability of the virus (41,42). However, the first coronavirus Nsp13 structure MERS-CoV Nsp13 was not resolved until 2017 due to the inherent flexibility of the protein (43). Meanwhile, Nsp13 is related to human proteins with a series of functions, such as regulating cellular protein metabolism, regulating protein localization, Golgi apparatus, cytoskeleton, intracellular non-membrane-bound organelles and so on. These functions may be closely related to the vesicle transport process during virus infection, regulate the localization and metabolism of proteins, and interfere with the metabolic process of the virus in the body. In this way, it is possible to interfere with the metabolism of the virus by interfering with human proteins that interact with Nsp13.

Moreover, the mapping of Nsp13 to gene clusters is mainly related to the PKA family and centrosome through GO and KEGG pathway analysis. The hub genes of PRKAR2B and PAKACA are members of the PKA family which encode the regulatory subunit and catalytic subunit of protein kinase A, respectively. PRKAR2B and PRKACA are enriched in hormone-mediated signaling, nucleotide binding, purine nucleotide binding, activation of protein kinase A activity by functional enrichment analysis. This may be related to the immune response produced by the body after the invasion of the virus. In T cells, cAMP-PKA pathway could transmit signals that inhibit activation and proliferation of T cells by inhibiting the expression of IL-2 (44,45). PKA protein kinase inhibitor can effectively relieve the inhibition of IL-2 expression on T cell proliferation and activation (46). PKA can also affect the production of B cell antibodies, but the effect is bi-directional. In mixed B lymphocytes, the production of antibodies decreased significantly with the increase of cAMP level (47). It was also reported that in the early stage of B lymphocyte activation, the addition of cAMP could promote antibody production, while long-term stimulation of cAMP inhibited antibody production. EPAC is another intracellular protein that mainly binds to cAMP and is an exchange protein directly activated by cAMP (48). The latest research shows that cAMP-EPAC plays an important role in the regulation of MERS-CoV replication (49).

Overall, it appears that PKA kinase inhibitors may increase the activity of T and B cells in the immune system to a certain extent. Therefore, the activation of cAMP-PKA signaling pathway could inhibit the function of some inflammatory factors of macrophages, such as TNF- α and IL-1 β, and down-regulate the inflammatory response (50). A recent report pointed out that the treatment of SARS-CoV-2 requires attention to anti-inflammation and control diabetes mellitus type 2 (T2DM). According to a previous report released by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention in the United States, patients with T2DM and metabolic syndrome may have a ten times higher risk of dying from infection with COVID-19 than other patients (51). Based on this result, we retrieved the drug ripasudil, an isoquinoline Rho-related kinase (ROCK) inhibitor which has been approved for the treatment of glaucoma and high intraocular pressure, and has good PKA inhibitory activity. Rho kinase is considered as a potential target in the treatment of metabolic syndrome and enhances the phosphorylation of insulin substrate 1 (IRS-1), leading to the occurrence of insulin resistance. So, the ripasudil may be effective in alleviating these symptoms (52).

As for the hub genes of AKAP9, PCNT, CEP135, CNTRL, CDK5RAP2, CEP250 and NINL, it was found that the above genes were mainly related to centrosome and microtubule tissue through functional enrichment analysis. Since the function of Nsp13 is the helicase, we speculate that the genes interacting with Nsp13 may be related to virus replication in vivo and cell cycle. However, there is no direct evidence at present. Besides, hub genes screened of the second round such as KAT2B and TADA3 are all related to protein acylation and transcriptional regulation, which partly confirms that the screened centrosome-related genes are related to genome replication and cell cycle.

Through searching the drug database, we found that some drugs have shown good antiviral activity in previous studies. BX-795 (3.125–25 mmol/L) dose-dependently inhibits HSV-2 replication and shows low cytotoxicity to host cells. BX795 targets many common ways of virus replication in cells, so it may be a new broad-spectrum antiviral drug that can be used to treat other viral infections (53). Anacardic acid (AnA) can inhibit the activity of various cellular enzymes including histone acetyltransferase (HATs), thereby inhibiting Hepatitis C virus (HCV) replication, translation, and virus secretion, without affecting cell viability (54). Epigallocatechin-3-gallate (EGCG) can also inhibit the replication of HCV in liver cells and inhibit the early stages of Japanese encephalitis virus infection. The study suggests EGCG as a lead compound for developing broad-spectrum antiviral agents. Compound 1(PMID: 15724976) blocks the binding of HIV-1 Tat to the co-activator PCAF which is essential for transcription and replication of the integrated HIV provirus (55). LTK-14 selectively inhibits P300-HAT in vivo and can inhibit histone acetylation in HIV-infected cells (56). Trans-resveratrol can significantly inhibit MERS-CoV infection after viral infection and reduce the expression of nucleocapsid (N) protein necessary for MERS-CoV replication. Specially, trans-resveratrol has been shown to be effective against various viral infections, including Epstein-Barr virus (EBV), enterovirus 71 (EV71), and herpes simplex virus (HSV) (57). Up to now, we have not found any drug targeting centrosome-related proteins. However, these pathways could be blocked by inhibiting their co-expression genes. Interestingly, Gordon DE, et al., mentioned that a natural product WDB002, can directly and specifically target CEP250. This means that targeting drugs for other centrosome-related proteins may be an aspect worth studying (11).

Conclusion

In summary, several hub genes were screened by bioinformatics based on 332 human proteins interacting with SARS-CoV-2 virus proteins. By analyzing the function of these genes, it was found that they were mainly related to some important biological processes and pathways, including PKA, centrosome and transcriptional regulation. A total of 15 drugs and 18 herb ingredients were screened to inhibit the biological response of the virus in vivo. A variety of drugs such as trans-resveratrol has shown good inhibitory activity in MERS-CoV, HCV, HIV and other viruses. In addition, further study is needed to confirm the results of our research. We hope our comprehensive bioinformatic analysis could provide insights to assist in the design of new drug, to help clinicians choose appropriate drugs for their SARS-CoV-2 patients.

(ARCMED_2020_1093)

Footnotes

Supplementary data related to this article can be found at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.arcmed.2020.11.009.

Supplementary data

References

- 1.Zumla A., Chan J.F., Azhar E.I., Hui D.S., Yuen K.Y. Coronaviruses - drug discovery and therapeutic options. Nat Rev Drug Discov. 2016;15:327–347. doi: 10.1038/nrd.2015.37. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Fehr A.R., Perlman S. Coronaviruses: an overview of their replication and pathogenesis. Methods Mol Biol. 2015;1282:1–23. doi: 10.1007/978-1-4939-2438-7_1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Cui J., Li F., Shi Z.L. Origin and evolution of pathogenic coronaviruses. Nat Rev Microbiol. 2019;17:181–192. doi: 10.1038/s41579-018-0118-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Morse J.S., Lalonde T., Xu S., Liu W.R. Learning from the past: possible urgent prevention and treatment options for severe acute respiratory infections caused by 2019-nCoV. Chembiochem. 2020;21:730–738. doi: 10.1002/cbic.202000047. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Li T. Diagnosis and clinical management of severe acute respiratory syndrome Coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2) infection: an operational recommendation of Peking Union Medical College Hospital (V2.0) Emerg Microbes Infect. 2020;9:582–585. doi: 10.1080/22221751.2020.1735265. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hui D.S.C., Zumla A. Severe acute respiratory syndrome: historical, epidemiologic, and clinical features. Infect Dis Clin North Am. 2019;33:869–889. doi: 10.1016/j.idc.2019.07.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Memish Z.A., Perlman S., Van Kerkhove M.D., Zumla A. Middle East respiratory syndrome. Lancet. 2020;395:1063–1077. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(19)33221-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.World Health Organization WHO Coronavirus Disease (COVID-19) Dashboard. https://covid19.who.int/ Retrieved from.

- 9.Initial genome release of novel coronavirus. 2020. http://virological.org/t/initial-genome-release-of-novel-coronavirus/319?from=groupmessage Retrieved from.

- 10.Zhang L., Lin D., Sun X. Crystal structure of SARS-CoV-2 main protease provides a basis for design of improved α-ketoamide inhibitors. Science. 2020;368:409–412. doi: 10.1126/science.abb3405. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Gordon D.E., Jang G.M., Bouhaddou M. A SARS-CoV-2 protein interaction map reveals targets for drug repurposing. Nature. 2020;583:459–468. doi: 10.1038/s41586-020-2286-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Tang Z., Kang B., Li C., Chen T., Zhang Z. GEPIA2: an enhanced web server for large-scale expression profiling and interactive analysis. Nucleic Acids Res. 2019;47(W1):W556–W560. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkz430. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Shannon P., Markiel A., Ozier O. Cytoscape: a software environment for integrated models of biomolecular interaction networks. Genome Res. 2003;13:2498–2504. doi: 10.1101/gr.1239303. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Huang da W., Sherman B.T., Lempicki R.A. Bioinformatics enrichment tools: paths toward the comprehensive functional analysis of large gene lists. Nucleic Acids Res. 2009;37:1–13. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkn923. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Huang da W., Sherman B.T., Lempicki R.A. Systematic and integrative analysis of large gene lists using DAVID bioinformatics resources. Nat Protoc. 2009;4:44–57. doi: 10.1038/nprot.2008.211. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Gene Ontology Consortium The Gene Ontology (GO) project in 2006. Nucleic Acids Res. 2006;34(Database issue):D322–D326. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkj021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ogata H., Goto S., Sato K., Fujibuchi W., Bono H., Kanehisa M. KEGG: Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes. Nucleic Acids Res. 1999;27:29–34. doi: 10.1093/nar/27.1.29. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Szklarczyk D., Gable A.L., Lyon D. STRING v11: protein-protein association networks with increased coverage, supporting functional discovery in genome-wide experimental datasets. Nucleic Acids Res. 2019;47(D1):D607–D613. doi: 10.1093/nar/gky1131. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Wishart D.S., Feunang Y.D., Guo A.C. DrugBank 5.0: a major update to the DrugBank database for 2018. Nucleic Acids Res. 2018;46(D1):D1074–D1082. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkx1037. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Cotto K.C., Wagner A.H., Feng Y.Y. DGIdb 3.0: a redesign and expansion of the drug-gene interaction database. Nucleic Acids Res. 2018;46(D1):D1068–D1073. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkx1143. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Armstrong J.F., Faccenda E., Harding S.D. The IUPHAR/BPS Guide to PHARMACOLOGY in 2020: extending immunopharmacology content and introducing the IUPHAR/MMV Guide to MALARIA PHARMACOLOGY. Nucleic Acids Res. 2020;48(D1):D1006–D1021. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkz951. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Huang L., Xie D., Yu Y. TCMID 2.0: a comprehensive resource for TCM. Nucleic Acids Res. 2018;46(D1):D1117–D1120. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkx1028. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Lipinski C.A., Lombardo F., Dominy B.W., Feeney P.J. Experimental and computational approaches to estimate solubility and permeability in drug discovery and development settings. Adv Drug Deliv Rev. 1997;46:3–26. doi: 10.1016/s0169-409x(00)00129-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kim S., Chen J., Cheng T. PubChem 2019 update: improved access to chemical data. Nucleic Acids Res. 2019;47(D1):D1102–D1109. doi: 10.1093/nar/gky1033. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Guo Y.R., Cao Q.D., Hong Z.S., Tan Y.Y., Chen S.D., Jin H.J., Tan K.S., Wang D.Y., Yan Y. The origin, transmission and clinical therapies on coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) outbreak - an update on the status. Mil Med Res. 2020;13(7):11. doi: 10.1186/s40779-020-00240-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Cheng V.C., Lau S.K., Woo P.C., Yuen K.Y. Severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus as an agent of emerging and reemerging infection. Clin Microbiol Rev. 2007;20:660–694. doi: 10.1128/CMR.00023-07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.de Wit E., van Doremalen N., Falzarano D., Munster V.J. SARS and MERS: recent insights into emerging coronaviruses. Nat Rev Microbiol. 2016;14:523–534. doi: 10.1038/nrmicro.2016.81. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Ge H., Wang X., Yuan X. The epidemiology and clinical information about COVID-19. Eur J Clin Microbiol Infect Dis. 2020;39:1011–1019. doi: 10.1007/s10096-020-03874-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Hoffmann M., Kleine-Weber H., Schroeder S. SARS-CoV-2 cell entry depends on ACE2 and TMPRSS2 and is blocked by a clinically proven protease inhibitor. Cell. 2020;181:271–280.e8. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2020.02.052. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Yan R., Zhang Y., Li Y., Xia L., Guo Y., Zhou Q. Structural basis for the recognition of SARS-CoV-2 by full-length human ACE2. Science. 2020;367:1444–1448. doi: 10.1126/science.abb2762. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Zhou P., Yang X.L., Wang X.G. A pneumonia outbreak associated with a new coronavirus of probable bat origin. Nature. 2020;579:270–273. doi: 10.1038/s41586-020-2012-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Rothlin R.P., Vetulli H.M., Duarte M., Pelorosso F.G. Telmisartan as tentative angiotensin receptor blocker therapeutic for COVID-19. Drug Dev Res. 2020;81:768–770. doi: 10.1002/ddr.21679. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Gurwitz D. Angiotensin receptor blockers as tentative SARS-CoV-2 therapeutics. Drug Dev Res. 2020;81:537–540. doi: 10.1002/ddr.21656. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Wang M., Cao R., Zhang L. Remdesivir and chloroquine effectively inhibit the recently emerged novel coronavirus (2019-nCoV) in vitro. Cell Res. 2020;30:269–271. doi: 10.1038/s41422-020-0282-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Mirza M.U., Froeyen M. Structural elucidation of SARS-CoV-2 vital proteins: Computational methods reveal potential drug candidates against main protease, Nsp12 polymerase and Nsp13 helicase. J Pharm Anal. 2020;10:320–328. doi: 10.1016/j.jpha.2020.04.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Adedeji A.O., Marchand B., Te Velthuis A.J. Mechanism of nucleic acid unwinding by SARS-CoV helicase. PLoS One. 2012;7:e36521. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0036521. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Xu J., Zhao S., Teng T. Systematic comparison of two animal-to-human transmitted human coronaviruses: SARS-CoV-2 and SARS-CoV. Viruses. 2020;12:244. doi: 10.3390/v12020244. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Jia Z., Yan L., Ren Z. Delicate structural coordination of the Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome coronavirus Nsp13 upon ATP hydrolysis. Nucleic Acids Res. 2019;47:6538–6550. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkz409. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Shum K.T., Tanner J.A. Differential inhibitory activities and stabilisation of DNA aptamers against the SARS coronavirus helicase. Chembiochem. 2008;9:3037–3045. doi: 10.1002/cbic.200800491. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Jang K.J., Jeong S., Kang D.Y., Sp N., Yang Y.M., Kim D.E. A high ATP concentration enhances the cooperative translocation of the SARS coronavirus helicase nsP13 in the unwinding of duplex RNA. Sci Rep. 2020;10:4481. doi: 10.1038/s41598-020-61432-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Tanner J.A., Zheng B.J., Zhou J. The adamantane-derived bananins are potent inhibitors of the helicase activities and replication of SARS coronavirus. Chem Biol. 2005;12:303–311. doi: 10.1016/j.chembiol.2005.01.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Lee C., Lee J.M., Lee N.R. Aryl diketoacids (ADK) selectively inhibit duplex DNA-unwinding activity of SARS coronavirus NTPase/helicase. Bioorg Med Chem Lett. 2009;19:1636–1638. doi: 10.1016/j.bmcl.2009.02.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Hao W., Wojdyla J.A., Zhao R. Crystal structure of Middle East respiratory syndrome coronavirus helicase. PLoS Pathog. 2017;13:e1006474. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1006474. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Rincón M., Tugores A., López-Rivas A. Prostaglandin E2 and the increase of intracellular cAMP inhibit the expression of interleukin 2 receptors in human T cells. Eur J Immunol. 1988;18:1791–1796. doi: 10.1002/eji.1830181121. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Baker P.E., Fahey J.V., Munck A. Prostaglandin inhibition of T-cell proliferation is mediated at two levels. Cell Immunol. 1981;61:52–61. doi: 10.1016/0008-8749(81)90353-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Anastassiou E.D., Paliogianni F., Balow J.P., Yamada H., Boumpas D.T. Prostaglandin E2 and other cyclic AMP-elevating agents modulate IL-2 and IL-2R alpha gene expression at multiple levels. J Immunol. 1992;148:2845–2852. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Teh H.S., Paetkau V. Biphasic effect of cyclic AMP on an immune response. Nature. 1974;250:505–507. doi: 10.1038/250505a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Tao X., Mei F., Agrawal A. Blocking of exchange proteins directly activated by cAMP leads to reduced replication of Middle East respiratory syndrome coronavirus. J Virol. 2014;88:3902–3910. doi: 10.1128/JVI.03001-13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Schmidt M., Dekker F.J., Maarsingh H. Exchange protein directly activated by cAMP (epac): a multidomain cAMP mediator in the regulation of diverse biological functions. Pharmacol Rev. 2013;65:670–709. doi: 10.1124/pr.110.003707. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Zhong W.W., Burke P.A., Drotar M.E., Chavali S.R., Forse R.A. Effects of prostaglandin E2, cholera toxin and 8-bromo-cyclic AMP on lipopolysaccharide-induced gene expression of cytokines in human macrophages. Immunology. 1995;84:446–452. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Garg S., Kim L., Whitaker M. Hospitalization rates and characteristics of patients hospitalized with laboratory-confirmed coronavirus disease 2019 — COVID-NET, 14 States, March 1–30, 2020. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2020;69:458–464. doi: 10.15585/mmwr.mm6915e3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Jahani V., Kavousi A., Mehri S., Karimi G. Rho kinase, a potential target in the treatment of metabolic syndrome. Biomed Pharmacother. 2018;106:1024–1030. doi: 10.1016/j.biopha.2018.07.060. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Su A.R., Qiu M., Li Y.L. BX-795 inhibits HSV-1 and HSV-2 replication by blocking the JNK/p38 pathways without interfering with PDK1 activity in host cells. Acta Pharmacol Sin. 2017;38:402–414. doi: 10.1038/aps.2016.160. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Hundt J., Li Z., Liu Q. The inhibitory effects of anacardic acid on hepatitis C virus life cycle [published correction appears in PLoS One 2015;10:e0122379] PLoS One. 2015;10:e0117514. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0117514. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Zeng L., Li J., Muller M. Selective small molecules blocking HIV-1 Tat and coactivator PCAF association. J Am Chem Soc. 2005;127:2376–2377. doi: 10.1021/ja044885g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Mantelingu K., Reddy B.A., Swaminathan V. Specific inhibition of p300-HAT alters global gene expression and represses HIV replication. Chem Biol. 2007;14:645–657. doi: 10.1016/j.chembiol.2007.04.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Lin S.C., Ho C.T., Chuo W.H., Li S., Wang T.T., Lin C.C. Effective inhibition of MERS-CoV infection by resveratrol. BMC Infect Dis. 2017;17:144. doi: 10.1186/s12879-017-2253-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.