Abstract

With the outbreak of COVID-19 being declared a pandemic by the World Health Organisation, educators worldwide are facing a major challenge in how to adapt, become resilient, and to monitor/detect potential safeguarding issues amid nursery and school closures. Online communication between parents, children and early years practitioners/teachers rapidly became a new ‘norm’ during the first lockdown in the UK. This paper reports on quantitative and qualitative findings from 55 participants compromised of early years practitioners and primary school teachers working with 3 to 8 years old children in the South-East of England. Methods of data collection deployed online surveys and a qualitative focused questionnaire, to capture what measures nurseries and primary schools adopted to ensure children are safeguarded. We argue that pressure on early years practitioners and teachers to monitoring safeguarding children by using various online platforms is physically and emotionally challenging. This paper highlights the difficulties of detecting safeguarding issues amid school closures, which should be avoid during further future closures.

Keywords: COVID-19, Safeguarding, Early years practitioner, Teacher, Lockdown

1. Chronology of the pandemic in the UK: March and April 2020

The first UK confirmed death from COVID-19 was reported on 5th March 2020 (Public Health England, 2020). With the COVID-19 pandemic gripping the UK, the government came under increasing pressure to close nurseries and schools. A question on closing schools became a regular feature from journalists to the government panel at the daily COVID-19 Downing Street press briefing. University College, London has reported (Roberts, 2020) that keeping nurseries and schools closed has little impact on stopping the spread of the COVID-19, despite children being labelled as ‘super spreaders’ and ‘carriers’ of the coronavirus (Withers, 2020). This raises concerns as to whether the cost of nursery and school closures outweighs the benefits, as it potentially impacts harmfully on the well-being of children and early years teachers (EYT).

Delaying school closures was a controversial government strategy. Stewart and Busby (2020) reported that Sir Vallance, the UK government’s chief scientific advisor, defended the government’s ‘herd immunity’ strategy, which included keeping schools open and delaying ‘lockdown’. Davis and Lohm (2020) argued that numerical narratives on mathematical models shaped the government’s response to the COVID-19 pandemic as these models require monitoring performance through analysing data on transmission, mortality, effectiveness of treatment, vaccine and containment. However, it was becoming apparent that schools were struggling to keep up children’s attendance, as parents took their children out of school for fear of catching the coronavirus (Adams et al., 2020). In addition, EYT withered to an unacceptable level, as the public (as well as EYT) followed government guidance on self-isolation.

On 18th March 2020 the Prime Minister, Boris Johnson, announced in his daily COVID-19 address the closure of all schools including nurseries in England, until further notice. This undoubtedly would have a major impact on child development and on professional practice. Guidance was issued on social-distancing (Department of Health and Social Care, 2020) and schools were asked to remain open as a ‘childminding’ service for ‘keyworkers’, with a list of who would qualify as a keyworker being published by the government (Department for Education, 2020a). This announcement brought both relief and apprehension for parents, students sitting milestone exams (GSCE and A-Levels) and educational providers.

There was a unified sense of relief that the UK had at last followed most of Europe and implemented school closures. However, along with this came uncertainty and concerns, with the latter, for example, child-poverty and children not getting ‘the only square meal a day’, which they would receive if they were still at school. Extraordinary measures were taken to ensure that schools’ vulnerable learners from families on low-incomes were still able to benefit from these free school meals (Weale, 2020a). Yet, there was very little media coverage on schools ensuring that safeguarding issues were detected and monitored, especially child neglect or child abuse, as well as the less common but still important issues, particularly amongst certain ethnic groups, of forced marriage (FM) and female genital mutilation (FGM). Although the UK government issued guidance on safeguarding (Department for Education, 2020b, p. 3), which stated: “It is important that all staff who interact with children, including online, continue to look out for signs a child may be at risk.” However, there was no direction on how to look for signs where children or their parents were unable to engage online during nursery and primary school closures.

On 6th April 2020, the Home Secretary, Priti Patel addressed the need to support victims of domestic abuse including children and announced funding in the sum of £2 million. The national domestic abuse helpline has reported a surge of 25 percent in online and telephone calls for help amid the COVID-19 lockdown (Kelly & Morgan, 2020). However, Weale (2020b) reported that child protection referrals, mainly made by educational institutions and health care professionals, have plunged by more than 50 percent. Local authorities have attempted to monitor vulnerable children by urging that they attended schools amid lockdown. Nevertheless, worried parents have been very reluctant to send their children to school as they are concerned about the risk of other family members catching COVID-19, and their children being stigmatised as vulnerable (Weale, 2020b). As school closures continue, Ali and Alharbi (2020, p. 728) argue that COVID-19 has affected all the sectors of society. Evidently, vulnerable children have become invisible to the detection of safeguarding issues.

On 16th April 2020 the UK government reviewed and extended the original COVID-19 lockdown (announced on 24th March 2020) for a further three weeks. It is known that since lockdown has been in operation, calls to helplines for child and adult abuse have experienced exponential increases (Kelly & Morgan, 2020). In addition, whilst the advice from the Foreign and Commonwealth Office, 2020a, Foreign and Commonwealth Office, 2020b is against non-essential travel worldwide, airlines are greatly reducing, but not stopping the availability of flights. Some countries have shut their borders to incoming travellers, or are restricting entry to foreign nationals. However, this still leaves open the opportunity for FGM and FM to take place abroad without detection. In these circumstances, how are teachers expected to monitor such safeguarding issues amid school closures, and now through ‘lockdown’? Therefore, it is essential to address the role of early years practitioners and teachers in addressing safeguarding concerns, in particular, how to safeguard children who may be at an increased risk of abuse, harm and exploitation from a range of sources. Additional consideration needs to be given to how to make early contingency plans for any future variation or tightening of restrictions. The question on how to detect and prevent forced marriage (FM) and female genital mutilation (FGM) remains an increased concern.

2. UK government policy

The early years foundation stage (EYFS) (DfE, 2017) statutory framework sets the standards that all early years providers must meet to ensure that children aged 0 to 5 learn and develop well and are kept healthy and safe. Early years setting are nurseries, children centres and childminding services. Section 3.4 of the guidance states that:

‘Providers must be alert to any issues of concern in the child’s life at home or elsewhere. Providers must have and implement a policy, and procedures, to safeguard children.’ (DfE, 2017: 16)

The guidance suggests that appropriate policy on safeguarding must be implemented; however, the guidance does not address how to detect abuse or neglect when communicating with children online. Section 3.6 of the guidance highlights how to identify signs and symptoms of abuse and neglect through focusing on indicators that tend to be mainly visual signs, such as unexplained bruising. A further document/guidance is required that outlines indictors for early years practitioners and teachers on how to detect abuse through online communication with children. For example, the mere lack of engagement itself may be an indicator. To support early years providers during the coronavirus (COVID-19) pandemic, the government temporarily disapplied and modified certain elements of the EYFS (DfE, 2017) statutory framework. This was to allow providers greater flexibility to respond to changes in workforce availability and potential fluctuations in demand, while still providing care that is high quality and safe. The original disapplication came into force on 24 April 2020 with the end planned to be on 25 September 2020.

Another important document is the Working Together to Safeguard Children (HM Government, 2018) which is a guide to inter-agency working to safeguard and promote the welfare of children. Whilst it is parents and carers who have primary care for their children, local authorities, working with partner organisations and agencies, have specific duties to safeguard and promote the welfare of all children in their area. This document provides a link to the legislation surrounding criminalising the practice of forced marriage (FM) and female genital mutilation (FGM) (Behaviour, Crime, & policing Act, 2014). The government has identified early years practitioners and teachers as frontline workers which included the role for detecting and preventing FM and FGM. This perception needs now to be widened to incorporate practice online, along with maintaining communication with parents, carers and monitoring potential safeguarding issues.

3. The role of early years practitioners and teachers in detecting safeguarding concerns

One important pastoral role that early years practitioners and teachers have is to safeguard children from harm. It was acknowledged by the End of Violence Against Children (EVAC, 2020) that the COVID-19 pandemic is having a devastating impact on children by exposing children to increased risk of violence including maltreatment, gender-based violence and sexual exploitation. EVAC claims that governments have a central role to play in ensuring that COVID-19 prevention and response plans integrate age appropriate and gender sensitive measures. These measures should protect all children from violence, neglect and abuse. Therefore, child protection services and workers must be designated as essential and resourced accordingly. In England, the Department for Education (2020b) has issued detailed guidance to all educational institutions, including nurseries, suggesting what educational institutions need to do in collaboration with the local authority to report abuse.

Other literature problematises FM and FGM by highlighting them as barbaric practices (Brah, 1996; Chantler, 2012) that trivialise and omit one or both parties’ consent to the marriage (Foreign and Commonwealth Office, 2020a, Foreign and Commonwealth Office, 2020b). Khan’s (2019) research found that the UK government appeared to have constructed teachers’ roles as ethical gate-keepers, and possibly views them as best positioned to tackle social issues with young persons, such as bullying, drug-use and FM. Teachers are expected to detect FM, FGM and abuse (Foreign and Commonwealth Office, 2014; Khan, 2019) as part of their safeguarding role. More research is required in this area to uncover and examine the impact on teachers of implementing FM policy. This study highlights the impact on teachers’ of maintaining this safeguarding role through the COVID-19 pandemic.

4. Methodological approach

The methodology for this paper combined a review and analysis of secondary data (namely policy documents, literature, legislation and statistics) and empirical data once ethical approval was gained. Data for this paper were collected within the first three weeks of the UK lockdown (i.e. between 20th March 2020 and 10th April 2020). The researchers acknowledge that this was a limited period, but the aim was to capture views about the challenges of the first few weeks of school and early years settings closure.

Data collection involved collecting data by using two methods. First, we collected data through online survey while the second set of data was collected using two open ended question. The questions asking early years practitioners and teachers how they detect safeguarding issues. As Robson (2011) suggests, multiple methods are a useful way of addressing different aspects of the topic. Participants were recruited using snowballing technique targeting early years practitioners and teachers who work with children aged 3 to 8 years old in the South-East of England. The survey was used to determine if safeguarding concerns have been addressed, while stage two answers were sought to how nurseries and primary schools were dealing with safeguarding concerns. Participants were asked to write about their experiences during lockdown.

The online survey consisting of ten questions aimed to gather information about safeguarding children whilst nurseries and schools are closed amid COVID-19. The online survey avoided questions that required confidential information being revealed or the need to report criminality. All data were collected anonymously through a mobile-link to the survey. The participants were informed that by completing and submitting the survey they were consenting to their responses being used as data. A total of 100 invitations to complete the survey were sent out to a targeted audience, recruited from personal contacts of both the researchers as well as using snowballing techniques. The response rate equated to 55 percent, which the literature suggests is above the average response rate to surveys (Lewin, 2011).

All closed question responses were pre-coded numerically (for example, no = 0, yes = 1). Data were analysed within two sections; in the first section, the online survey results were presented through graphs related to e-learning and in the second section, qualitative data were analysed thematically to highlight issues surrounding safeguarding and emotional experiences of the participants.

5. Data analysis and results

5.1. Quantitative data analysis

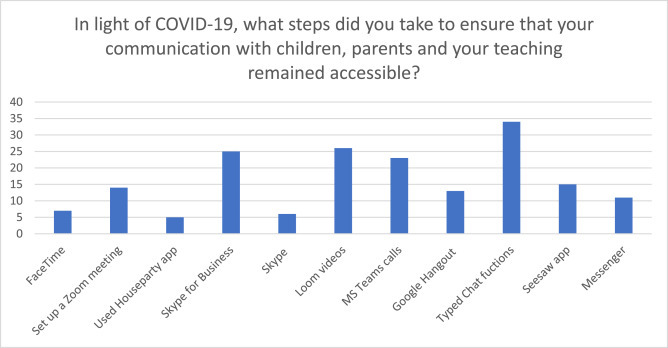

The results from the survey are presented through graphs and numerical analysis. We asked the participants, in light of the lockdown, what steps they took to ensure that communication with children and their parents, along with their teaching remained accessible to learners akin to face-to face contact.

Participants answers revealed that the most popular medium for maintaining contact with pupils and parents are ‘typed chat functions’ which was the method used by 34 participants. ‘Typed chat function’ may refer to any kind of communication and interpersonal relationships in cyberspace using the chat channel as an interaction medium (Peris et al., 2002). This kind of communication offers a real-time transmission of text messages from sender to receiver that are generally informal and short and that enables participants to respond quickly. Thereby, a feeling similar to a spoken conversation is created, which distinguishes chatting from other text-based online communication forms, such as email. A number of free platforms are available for maintaining face-to-face contact. However, this appears not to be the preferred option.

A further question asked related to how participants felt about using online platforms for communication. McGrath (2020) reported that generally, there appeared to be an air of panic surrounding the sudden move to e-communication and e-learning among teachers. Responses to this question have not reflected this panic mode. Although, more than a third of participants (36%) felt unprepared, they did not report that they ‘panicked’. Being unprepared undoubtedly resulted from the immediate move to e-learning, without sufficient warning. There may be an element of lack of training on the platforms required to use ‘e-working’. Almost a third of participants reported that they had not used VLE before COVID-19. A further 17% of participants admitted to ‘feeling anxious’ and 17% reported feeling ‘neutral. The reason for being neutral, as Khan’s (2019) study highlights, is that teachers negotiate their voice in favour of political correctness and neutrality.

To the question, ‘how parents and children reacted to the changes made to their everyday practice’, two-thirds of participants reported that most of the children and parents engaged with the new ways of communication and e-learning. Whilst almost a fifth of participants, 18%, reported that only a few of the children and parents engaged. This raises concerns, not only relating to the detrimental effect of being absent from education, but also to whether there are any underlying safeguarding issues.

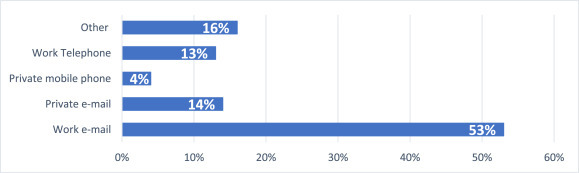

To the question ‘how participants dealt with those families who have not engaged’, Fig. 2 shows measures taken to address this issue.

Fig. 2.

Measures taken to address those who are not engaging.

As Fig. 2 shows, the most common method to establish some kind of communication was through emailing, 67% (53% using work email and 14% using personal email addresses). Only 18% of participants use the phone/mobiles to contact their learners or their families. Unfortunately, data was not collected on whether this approach was successful.

5.2. Qualitative data findings

The aim of the two qualitative questions that the participants were asked was to capture responses about how nurseries and schools are dealing with safeguarding. The qualitative questions were:

-

1.

How are you detecting potential safeguarding issues amid COVID-19 educational institution closures? and

-

2.

What is the impact of your educational institution’s closure on you as an educator?

6. Responses to question 1: How are you detecting potential safeguarding issues amid COVID-19 educational institution closures?

Owing to the immediate imperative to close all educational institutions in the UK, this created a ‘chaotic’ situation. One participant highlighted how the priority was to concentrate on arranging online teaching and not establishing contact with all the parents and children. This particular participant reported that:

“Good point-hadn’t thought about this [safeguarding], focused on teaching and creating online sessions.” (Participant 25).

This response demonstrates how participants where challenged with prioritising their teaching role over their pastoral role (Khan, 2019). In this particular institution the role of the safeguarding lead, who should be co-ordinating and taking a lead on safeguarding issues, should have issued guidance. The importance of institutions providing clarity is also highlighted in the EYFS (2017) guidance. Conversely, several participants voiced how they had encountered challenges with identifying safeguarding issues. “It’s becoming more difficult. I’m not completely sure of how to detect it right now.” (Participant 27).

Despite the Department for Education issuing COVID-19 guidance on safeguarding (Department for Education, 2020b) a week after school closures, participants were still struggling to monitor safeguarding issues effectively. A unified response from the participants appears to be that identifying safeguarding issues amid COVID-19 school closures is near impossible. “… there are few or no ways we are detecting safeguarding issues, especially FGM or forced marriage.” (Participant 22).

In early April, further guidance was issued on vulnerable children and young people (Department for Education, 2020c). This guidance provides advice on supporting children and young persons who are already identified as vulnerable and arranging for them to continue attending school. One participant demonstrated how matters remain complex even with such guidance in place.

“We have received conflicting information; on the one hand the government guidance says children are only to attend if they have a social worker, elsewhere it says providers can use their judgement. What about all those families who don’t meet the ‘thresholds’?” (Participant 3).

Participants explained that although vulnerable learners or their parents were being emailed, very few had responded. “We created a list of vulnerable students but despite this, very few have responded to our e-mail. I am rather concerned about this.” (Participant 24).

Most participants described how their institution set up well-being teams to monitor safeguarding issues. These teams communicated with parents once a fortnight and, in some instances, once a week. However, these processes were not always successful.

“We have phone consults with parents and keep in touch via a closed pre-school group. But the families that would be on the ‘radar’ are not participating either, so safeguarding is a real concern during COVID-19.” (Participant 2).

“It’s very difficult to detect these issues as these children are the least likely to engage, or to be able to engage, from an unsafe environment. These students may not be able to access learning or communication methods.” (Participant 42).

To some extent the hands of teachers are tied. Parents and carers are under no obligation to send learners to school amid school closures. Weale (2020b) reported how parents are concerned about sending their children to school and increasing the risk of coronavirus spreading within their household. Also, by attending school, vulnerable learners are highlighting their vulnerability to their peers, which some families fear will attract stigmatism (Weale, 2020b). This potentially makes learners vulnerable to peer hierarchies and discrimination.

The following quote highlights the concern early years practitioners and teachers are facing by not knowing how to address the unknown, as it was said that “… we are very concerned that some of our non-vulnerable families will become vulnerable during this period and we will be unaware.” (Participant 33). This is a real undetectable risk, which supports the argument as to whether school closures are causing more harm than good. Lockdown can create a stressful and overbearing home environment. This could generate new potential risks to children physically, mentally as well as emotionally. Moreover, there may be financial implications of the lockdown that spirals families into poverty. Unless children are from families where free-school meals are offered, or they have previously been classified as at risk of harm, they will go undetected.

Most participants describe online communication as the only form of communication that they have with children and their families. Often telephone contact with parents is unsuccessful. One participant explains that:

“I have been keeping touch with my parents through email and Tapestry. I have asked parents to upload photos of the children and I have sent them some with messages for the children, although not all have responded. I think this is the most we can do under the circumstances.” (Participant 6).

This illustrates how educators are making desperate attempts to monitor safeguarding issues in an impossible situation. Four participants utilised the platform Tapestry to communicate with parents and share confidential information on their children. Tapestry is an online learning journal that is widely used in an early years setting in the UK.

7. Responses to question 2: What is the impact of your educational institution’s closure on you as an educator?

The participants provided a strong emotional response to the school closures, akin to a sense of bereavement. Emotional investment in teaching is not uncommon as reported by Yoo and Carter (2017). Participants 2 reported that:

“I experienced a feeling of loss almost grief like when schools closed … we may not see those children again, who we have nurtured since they were two …” (Participant 2)

Early years practitioners and teachers strive to engage with each child to enable them to reach their full potential. The COVID-19 related closures have unexpectedly interfered with this process. Responses indicted that participants have an overwhelming and powerful emotional connect with their children, which supports the research conducted by Mikuska and Fairchild (2020). Their qualitative analysis revealed that working with children is emotional, and in many cases the emotional aspect of the work goes unrecognised especially when practitioners and teachers are dealing with safeguarding cases. Stress and worry were the two dominant emotional responses that emerged from the participants. For example, participant 3 explained the stresses of the situation:

“very, very stressful … not knowing if we will get paid … I think for me, my primary concern is the impact on some of our families, I can’t seem to shake off worrying about them.” (Participant 3).

The element of stress emerged as an indicator of financial hardship for the participants, as well as the pressure to move to an online mode quickly and efficiently.

Some participants thought that the children will be unequipped to return straight after the lockdown. Participant 2 was very concerned about the ‘transition’ period, from nursery (pre-school) class to reception class, where more formal teaching starts. It was reported that:

“We are due to lose 2/3 of our cohort in July to the big school and they were not ready or prepared for the transition. We also collectively worry about the children that went up last year, having to move to year one following just six months in reception.” (Participant 2).

What came through the data is a sense of the participants’ being ‘robbed’ of the opportunity to complete children’s journey with them. A number of the participants stated that they miss working with the children for whom they cared. Participant 6 for example reported that: “I have been missing the children and been thinking about what they are doing.” (Participant 6).

This illustrates the bond that develops between the educator and learner. A child who attends nursery full-time will spend more time during the week, in term-time, at their nursery than with their parents/carers. Therefore, an early years practitioner would inevitably develop a bond of trust, securing and wanting the best for their children (Mikuska & Lyndon, 2018). Not having that daily contact could trigger a sense of loss and longing.

Only one participant shared a sense of relief yet at the same time guilt at the school closures. This emerged from concerns about protecting their vulnerable family members from the risk of contracting COVID-19.

“… closing the school to stop the spread of the virus has affected me positively, as I have very vulnerable family members and it has therefore enabled me to keep them safe … Finally there is a feeling of guilt that I am at home because of vulnerable family members, when colleagues are still putting themselves at risk to be at school for key workers children.” (Participant 4).

This statement captures the internal struggles and pressures of performing the role of a ‘good’ and ‘proper’ teacher (Kelchtermans, 2005), with balancing their personal identities and responsibilities. Nevertheless, a sense of having done well despite the circumstances was also prevalent. For example, participants 38, 40 and 45 all reported that; “Overall I felt positive. I have learnt some skills that I will use in the future.”; “I felt very positive about the whole closure. I am proud to be a teacher.”; and “When sessions went well, it had been great to connect with pupils, despite the constraints.”

These comments clearly reflect how positively some participants feel when they successfully address the demands of their organisation. Positive experiences enhance learning and teaching which is directly linked to learners’ attainment and educational achievement. Yet, little is written about the importance of emotions in education and how emotion is embodied in teaching. This is surprising, especially when the position is taken that emotions play a central role in the construction of the teacher’s subjectivity (Zembylas, 2005).

It is important to highlight that these responses were at the beginning of the first lockdown when most early years practitioners and teachers were dealing with multiple and complex tasks. The analysis has attempted to provide a picture of how a small number of participants have adapted their practices due to school closures. The results from the survey suggest that participants responded very quickly to a government decision. However, this response was not without issues, as 31% of respondents received no support from their nurseries and schools. Most of the participant expressed concerns about how to detect safeguarding issues. For example, participants 2, 3, 24 and 42 expressed worry for children for whom they care, which they carried into their private space. The research findings demonstrated that the caring part of the educator is endless, which needs engagement with emotional labour as ‘skilled work’ (Bolton, 2004) to the personal costs of individual teachers. This further indicates that teachers are required to manage their emotions and relationships with learners and parents. As Brown et al. (2001) argued, the emphasis in the education environment is on creativity, rather than on emotional labour, and keys skills are seen as communication, team-working, individual initiative and self-reliance. Therefore, it can be argued that the work teachers are doing is emotion work, which goes unrecognised (Mikuska & Fairchild, 2020).

This research reveals that participants worked hard to deal with complex issues in a short period of time, which impacted on their emotional state. Beside some negative impact, there were also positive feelings that were associated with helping ‘others’, and expressing participants’ affections towards children, coupled with developing new skills. Mikuska and Fairchild’s (2020) and Yoo and Carter’s (2017) work on emotions recognises emotions in education and treats it as unrecognised and sufficient for political debate that requires further empirical study. This short survey builds on Mikuska and Fairchild (2020) work as it illustrated that emotions are part of the participants’ professional role, which should be recognised as skilled work.

Furthermore, the UK government, through various statutory guidance, has provided a comprehensive safeguarding framework. This paper highlights three statutory provisions that set out guidance for participants and educational institutions (such as nurseries and primary schools) on how to embed safeguarding into their practice. Unfortunately, it would appear that even with their best intentions, some of the participants were unable to implement safeguarding strategies to monitor and detect safeguarding issues through online communication with children and their parents. Despite schools having designated safeguarding officers, internal school guidance and policies for early years practitioners on how to monitor and detect safeguarding issues online were not forthcoming.

The research identified how some participants were unable to communicate with some children and their parents amid school closures. There may have been a simple explanation for this, such as electronic devises were not available to the children to keep in touch with the participants. However, from a safeguarding perspective a lack of communication raises concerns to whether some children might have been taken abroad and forced in a marriage. The ability to detect and monitor absences, disappearances and changes in children’s behaviour has significantly reduced during school closures, hence, raising fears of an increase in forced marriages during this period.

8. Conclusion

With the outbreak of COVID-19 being declared a pandemic, this paper gave chronological insight about how the UK government dealt with lockdown within the first three weeks. Since online communication between parents, children and early years practitioners/teachers was the only way to maintain some form of connection, we discussed which platforms (See Fig. 1 ) were used. We also highlighted the issues around early years practitioners/teachers keeping communication with all the children. Our research revealed that even when the most robust safeguarding strategies are in place, it is difficult to follow these strategies when an unexpected situation occurs.

Fig. 1.

Online platforms.

We acknowledge that new safeguarding processes are difficult to adapt when early years practitioners and teachers are required to quickly move communication with parents and children online. Therefore, a review is required to ensure that a flexible safeguarding framework is developed that can seamlessly enable detection of safeguarding issues in the classroom to an online mode, amid school closures due to Covid-19. Although the quantitative data suggest that early years practitioners and teachers try their best to ensure the best outcome for children, our qualitative data illustrate that this was difficult to maintain during the first three weeks of the lockdown. The emotions expressed by the participants relating to school closures, demonstrates the complexity of balancing personal and professional practices (Khan, 2019).

At the time of writing this paper, safeguarding issues were arising, as a result of using online platforms. It was not long before criminality emerged within these platforms, and computer hackers took advantage of captive audiences (Farrer, 2020). This resulted in authorities in several countries suspending the use of Zoom by teachers. This raises safeguarding issues as parents have access to children other than their own, whom they can see and directly speak to during these e-learning sessions.

The true extent of the impact of nursery and school closures on teachers and children will emerge once the institutions have re-opened. Undoubtedly, the question as to whether it was worth closing schools amid the COVID-19 pandemic will be revisited, and indeed provides the basis for a further study. This small-scale study captured the initial impact and reactions to nursery and school closures. This research will benefit policymakers, early years practitioners, teachers and safeguarding officers in nurseries and schools, through engaging them in the debate of detecting, monitoring and maintaining safeguarding issues with children online, amid school closures.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors. The views expressed in this work are those of the authors.

Notes on contributors

Dr Tehmina Khan works as a senior law lecturer at London Metropolitan University. She is also a qualified solicitor (lawyer, not-practicing). Her research interests include forced marriage and teachers’ identities. Eva Mikuska is a senior lecturer in early childhood at the University of Chichester. Her research primarily focuses on (un)recognised emotional labour in education, and investigation of Hungarian minority education in Vojvodina, Serbia.

CRediT authorship contribution statement

Tehmina Khan: Conceived and designed the data:The data analysis was designed together with author 2. Collected the data: I was involved more with quantitative data collection. I designed the questionnaire for the survey. Contributed data or analysis tool:This part was done together with author 2. Performed analysis: This part was done together with author 2. Wrote paper: This part was done together with author 2. Other contribution: My EdD thesis focused on forced marriage and teachers’ identities. I was able to provide valuable insight into the law, policy, procedures and practices surrounding forced marriage and safeguarding. Éva Mikuska: Conceived and designed the data: The data analysis process was done together with author 1. Collected the data: Author 1 designed the questionnaire for quantitative part of the research, I was more involved in gathering qualitative data from early years practitioners and primary school teachers targeting reception class and Key stage 1 teachers. I am a member of the SEFDEY and ECSDN network through which I had access to the participants. Contributed data or analysis tool: My thesis followed a narrative approach which mean I have experience in how to analyse qualitative data. This part was done together with author 1. Performed analysis: This part was done together with author 1. Wrote paper: We wrote a paper together 50%–50%. Other contribution: I hold an Early Years Qualified Teacher status which means that I have an insider knowledge about how nursery and reception class professional practice operates. This includes safeguarding children and possible issues arising to do this. For many years I worked in various and diverse range of nurseries in London caring for 0–6 years old children. My specific contribution was understanding the policies and how they were followed by the participants.

Declaration of competing interest

No conflict of interest. This reserach did not recieve any fianace support.

Acknowledgement

We would like to thank the reviewers and Professor Judith Lathlean for her valuable comments.

Biographies

DrTehmina Khan works as a senior law lecturer at London Metropolitan University. She is also a qualified solicitor (lawyer, not-practicing). Her research interests include forced marriage and teachers’ identities

Éva Mikuska is a senior lecturer in the Department of Education, Health and Social Science at the University of Chichester, UK. Her work seeks to broaden current views on early childhood education and care in England with the aims to produce a more generative, ethical, and political way to enact ECEC research. Her language skills (native Hungarian, and Serbo-Croat) and her research enables her work to have synergy with a national and international set of ECEC researchers.

References

- Adams R., Weale S., Bannock C. 17 March. The Guardian; 2020. (Schools in England struggle to stay open as Coronavirus hits attendance). [Google Scholar]

- Ali I., Alharbi O.M.L. Science of the Total Environment; 2020. COVID-19: Disease, management, treatment, and social impact.https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/abs/pii/S0048969720323780?via%3Dihub Available online. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Behaviour, Crime and policing Act (2014). Available at: http://www.legislation.gov.uk/ukpga/2014/12/part/10. (Accessed 9 April 2020).

- Bolton S. Conceptual confusions: Emotion work as skilled work. In: Warhurst C., Keep E., Grugulis I., editors. The skills that matter. Palgrave; Basingstoke: 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Brah A. Routledge; London: 1996. Cartographies of diaspora, contesting identities. [Google Scholar]

- Brown P., Green A., Lauder H. Oxford University Press; Oxford: 2001. High skills: Globalization, competitiveness and skill formation. [Google Scholar]

- Chantler K. Recognition and the intervention in forced marriages as a form of violence and abuse. Trauma, Violence, & Abuse. 2012;13(3):176–183. doi: 10.1177/1524838012448121. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davis M., Lohm D. University Press; `Oxford: 2020. Pandemics, publics, and narrative. [Google Scholar]

- Department for Education Guidance for schools, childcare providers, colleges and local authorities in England on maintaining educational provision. 2020. https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/coronavirus-covid-19-maintaining-educational-provision/guidance-for-schools-colleges-and-local-authorities-on-maintaining-educational-provision Available at:

- Department for Education Guidance- coronavirus (COVID -19): Safeguarding in schools, colleges and other providers, 27 March. 2020. https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/covid-19-safeguarding-in-schools-colleges-and-other-providers/coronavirus-covid-19-safeguarding-in-schools-colleges-and-other-providers Available at:

- Department for Education Guidance - ‘coronavirus (COVID -19): Guidance on vulnerable children and young persons’, 1 April. 2020. Available at: https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/coronavirus-covid-19-guidance-on-vulnerable-children-and-young-people/coronavirus-covid-19-guidance-on-vulnerable-children-and-young-people.

- Department for Education [DfE] Statutory framework for the early years foundation stage. 2017. https://www.foundationyears.org.uk/files/2017/03/EYFS_STATUTORY_FRAMEW ORK_2017.pdf Available at:

- Department of Health and Social Care Guidance – ‘Staying at home and away from others (social distancing)’, 23 March. 2020. Available at: https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/full-guidance-on-staying-at-home-and-away-from-others.

- End of Violence Against Children Violence against children: A hidden crisis of the COVID-19 pandemic. 2020. https://www.end-violence.org/news-and-events Available at:

- Farrer M. ‘Singapore bans teachers using Zoom after hackers post obscene images on screens’, 11 April, the Guardian. 2020. https://www.theguardian.com/world/2020/apr/11/singapore-bans-teachers-using-zoom-after-hackers-post-obscene-images-on-screens Available at:

- Foreign and Commonwealth Office - HM Government Multi-Agency Statutory Guidance for dealing with forced marriage. 2014. https://www.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/322310/HMG_Statutory_Guidance_publication_180614_Final.pdf Available at:

- Foreign and Commonwealth Office ‘Foreign secretary’s Statement on coronavirus (COVID-19), 9 April. 2020. https://www.gov.uk/government/speeches/foreign-secretarys-statement-on-coronavirus-covid-19-9-april-2020 Available at:

- Foreign and Commonwealth Office Guidance - travel Advice against all non-essential travel: Foreign Secretary’s statement, 17 March. 2020. https://www.gov.uk/government/news/travel-advice-foreign-secreatary-statement-17-march-2020 Available at:

- HM Government Working Together to Safeguard Children A guide to inter-agency working to safeguard and promote the welfare of children. 2018. Available at: https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/779401/Working_Together_to_Safeguard-Children.pdf.

- Johnson B. ‘Prime minister’s Statement on coronavirus’, 18 March. 2020. https://www.gov.uk/government/speeches/pm-statement-on-coronavirus-18-march-2020 Available at:

- Kelchtermans G. ‘Teachers’ emotions in educational reforms: Self-understanding, vulnerable commitment and micropolitical literacy’. Teaching and Teacher Education. 2005;21(8):995–1006. [Google Scholar]

- Kelly J., Morgan T. ‘Coronavirus: Domestic abuse calls up 25% since lockdown, charity says’, BBC news, 6 April. 2020. https://www.bbc.co.uk/news/uk-52157620 Available at:

- Khan T. Forced to teach: Teachers negotiating their personal and professional identities when addressing forced marriage in the classroom. 2019. https://ethos.bl.uk/OrderDetails.do?uin=uk.bl.ethos.771579 Available at:

- Lewin C. Understanding and describing quantitative data. In: Somekh B., Lewin C., editors. Theory and methods in social research. Sage; London: 2011. pp. 220–230. [Google Scholar]

- McGrath C. UK school closures: Teachers panic over coronavirus as school staff left ‘in limbo. 2020. https://www.express.co.uk/news/uk/1256396/uk-school-closures-coronavirus-news-teachers-school-closures-exams-covid-19 The Daily Express, 17 March. Available at:

- Mikuska É., Fairchild N. Working with (post)theories to explore embodied and unrecognised emotional labour in English Early Childhood Education and Care (ECEC) Global Education Review. 2020;7(2):75–89. [Google Scholar]

- Mikuska É., Lyndon S. Embodied professional early childhood education and care teaching practices. In: Leigh J., editor. Conversations on embodiment: Teaching, practice and research - routledge research in higher education. Taylor & Francis; London: 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Peris R., Gimeno M.A., Pinazo D., Ortet G., Carrero V., Sanchiz M., Ibáñez I. Online chat rooms: Virtual spaces of interaction for socially oriented people. CyberPsychology and Behavior. 2002;5(1):43–51. doi: 10.1089/109493102753685872. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Publish Health England . 2020. Official statistics Deaths involving COVID-19, England and wales: Deaths occurring in March 2020.https://www.gov.uk/government/statistics/deaths-involving-covid-19-england-and-wales-deaths-occurring-in-march-2020 Available at: [Google Scholar]

- Roberts M. ‘Coronavirus: Scientists question school closures impact’, BBC news online, 6 April. 2020. https://www.bbc.co.uk/news/health-52180783 Available at:

- Robson C. 3rd ed. Blackwell Publishing; Oxford: 2011. Real world research: A resource for social-scientists and practitioner- researchers. [Google Scholar]

- Stewart H., Busby M. The Guardian; 2020. Coronavirus: Science chief defend UK plan from criticism. 13 March 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Weale S. 2020. ‘Volunteers mobilise to ensure children get fed during school closures’, the Guardian, 19 March.https://www.theguardian.com/education/2020/mar/19/volunteers-mobilise-to-ensure-children-get-fed-during-school-closures Availabale at. [Google Scholar]

- Weale S. ‘Fears for child welfare as protection referrals plummet in England. the Guardian. 2020 https://www.theguardian.com/society/2020/apr/08/fears-for-child-welfare-as-protection-referrals-plummet-in-england 8 April. Available at: (Accessed: 14 Aril 2020) [Google Scholar]

- Withers P. Coronavirus Warning: Children could be ‘Super-spreaders’ and should be social distancing. 2020. https://www.express.co.uk/news/uk/1260957/coronavirus-news-covid-19-super-spreaders-children-social-distancing The Daily Express, 26 March. Available at:

- Yoo J., Carter D. Teacher emotion and learning as praxis: Professional development that matters. The Australian Journal of Teacher Education. 2017;42(3) doi: 10.14221/ajte.2017v42n3.3. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Zembylas M. Discursive practices, genealogies, and emotional rules: A poststructuralist view on emotion and identity in teaching. Teaching and Teacher Education. 2005;21(8):935–948. [Google Scholar]