To the Editor:

Few studies have examined the frequency and importance of symptoms in patients with severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2) infection. Those that have been done were mostly small, often did not include individuals without SARS-CoV-2 infection, were retrospective (with attendant high risk of recall bias), and/or have focused only on hospitalized or ED patients.1 We describe symptoms in adult outpatients being tested for SARS-CoV-2 infection, and examine which are associated with having a positive reverse transcription-polymerase chain reaction (RT-PCR) swab result for SARS-CoV-2.

Methods

We conducted a prospective cohort study using data collected from every Albertan 18 years or older (including self-identified health-care workers) who produced a positive test result for SARS-CoV-2 or underwent swabbing for contact tracing due to a high-risk exposure (most commonly household contacts of a patient with coronavirus disease 2019 [COVID-19]) between March 1 and September 30, 2020. All data were collected using standardized questionnaires and entered into the Communicable Disease Outbreak Management (CDOM) database. As only patients with COVID-19 and high-risk contacts are eligible for CDOM, individuals who presented to a testing site with symptoms but were swab negative were not included. There were no missing data because we analyzed mandatory required fields in the reporting form. For patients who were tested multiple times, we examined only the data related to their first swab. Alberta has a publicly funded, universal access health-care system with integration of data from all hospitals and public health testing facilities in the province. The University of Alberta Health Research Ethics Board (Pro00101096) approved this project with a waiver of informed consent as all analyses were conducted using deidentified data.

We explored the associations between symptoms and SARS-CoV-2 swab positivity using positive likelihood ratios (PLRs) because they are less influenced by the underlying prevalence of the disease than ORs or positive predictive values.2 As the CDOM eligibility criteria could distort the underlying population distribution, we also performed a sensitivity analysis in only those adults being swabbed by Alberta Public Health as they were high-risk contacts.

Results

Between March 1 and September 30, 12,377 adult Albertans had at least one positive RT-PCR swab result for SARS-CoV-2 and 11,702 (95%) completed the CDOM questionnaire (mean age, 42.6 [SD, 16.6] years). Another 3,430 adult Albertans (mean age, 42.6 [SD, 15.8] years) who were contact traced and completed the symptom questionnaire, but subsequently had a negative RT-PCR swab result for SARS-CoV-2, were included.

The most commonly reported symptoms in the 11,702 adults with positive test results (only 5% of whom were hospitalized) were cough (49%), fever (41%), headache (34%), and sore throat (28%), but these were also common symptoms in the 3,430 high-risk contacts who were swab negative (Table 1 ). The symptoms most strongly associated with a positive SARS-CoV-2 swab result were anosmia/ageusia, decreased appetite, diarrhea, nausea/vomiting, malaise, muscle/joint pain, sneezing, fever/chills, and headache (Table 1). Cough, sore throat, and dyspnea were not associated with positive swab results in the general population. Amongst health-care workers, anosmia/ageusia, decreased appetite, fever/chills, muscle/joint pain, malaise, nasal congestion, cough, dyspnea, and headache were predictive of swab positivity (Table 1).

Table 1.

Baseline Characteristics and Symptoms Reported by Adults Tested for SARS-CoV-2 Infection

| Characteristic/Symptom | Frequency in Patients With Positive SARS-CoV-2 Swab Result (n = 11,702) | Frequency in Participants With Negative SARS-CoV-2 Swab Result (n = 3,430) | Positive Likelihood Ratio for SARS-CoV-2 Infection for That Variable in All 15,132 CDOM Participants (95% CI) | Positive Likelihood Ratio for SARS-CoV-2 Infection for That Variable in the 9,153 Patients Swabbed for High-Risk Contact Tracing (95% CI) | Frequency in Health-Care Workers With Positive SARS-CoV-2 Swab Result (n = 1,260) | Positive Likelihood Ratio for SARS-CoV-2 Infection if That Variable Is Present in Health-Care Workers (95% CI) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Demographics | ||||||

| 18-40 y | 5,905 (50.5%) | 1,766 (51.5%) | 0.98 (0.94-1.02) | 0.99 (0.95-1.04) | 661 (52.5%) | 0.94 (0.82-1.09) |

| 41-64 y | 4,566 (39.0%) | 1,359 (39.6%) | 0.98 (0.94-1.03) | 0.96 (0.91-1.01) | 558 (44.3%) | 1.07 (0.89-1.29) |

| 65 y and older | 1,231 (10.5%) | 305 (8.9%) | 1.18 (1.05-1.33) | 1.23 (1.08-1.40) | 41 (3.3%) | 1.13 (0.45-2.83) |

| Male sex | 6,192 (52.9%) | 1,186 (34.6%) | 1.53 (1.46-1.61) | 1.48 (1.41-1.56) | 309 (24.5%) | 0.97 (0.74-1.27) |

| Health-care worker | 1,260 (10.8%) | 174 (5.1%) | 2.12 (1.82-2.48) | 2.08 (1.76-2.45) | N/A | N/A |

| Smoking | ||||||

| Active smoker | 593 (5.1%) | 73 (2.1%) | 2.38 (1.87-3.03) | 2.41 (1.87-3.10) | 45 (3.6%) | 1.55 (0.57-4.27) |

| Active vaper | 176 (1.5%) | Suppressed due to cell count < 5 | 17.20 (5.50-53.80) | 14.78 (4.66-46.85) | 9 (0.7%) | N/A |

| Cannabis smoker | 291 (2.5%) | 22 (0.6%) | 3.88 (2.52-5.97) | 3.84 (2.46-6.01) | 20 (1.6%) | N/A |

| Symptoms | ||||||

| Anosmia/ageusia | 2,300 (19.7%) | 65 (1.9%) | 10.37 (8.13-13.23) | 8.71 (6.80-11.16) | 252 (20.0%) | 8.70 (3.28-23.06) |

| Decreased appetite/anorexia | 968 (8.3%) | 71 (2.1%) | 4.00 (3.15-5.07) | 2.73 (2.12-3.52) | 95 (7.5%) | 4.37 (1.40-13.65) |

| Diarrhea | 1,067 (9.1%) | 117 (3.4%) | 2.67 (2.22-3.22) | 1.91 (1.56-2.34) | 106 (8.4%) | 1.63 (0.84-3.15) |

| Nausea/vomiting | 893 (7.6%) | 98 (2.9%) | 2.67 (2.18-3.28) | 1.85 (1.48-2.31) | 89 (7.1%) | 1.37 (0.70-2.66) |

| Malaisea | 2,874 (24.6%) | 377 (11.0%) | 2.23 (2.02-2.47) | 1.72 (1.54-1.92) | 312 (24.8%) | 1.87 (1.26-2.77) |

| Fever/chills | 4,739 (40.5%) | 688 (20.1%) | 2.02 (1.88-2.17) | 1.51 (1.40-1.63) | 505 (40.1%) | 2.58 (1.81-3.68) |

| Headache | 3,934 (33.6%) | 570 (16.6%) | 2.02 (1.87-2.19) | 1.63 (1.50-1.78) | 469 (37.2%) | 1.66 (1.25-2.21) |

| Fatigueb | 415 (3.5%) | 63 (1.8%) | 1.93 (1.49-2.51) | 1.38 (1.03-1.85) | 49 (3.9%) | 1.69 (0.62-4.63) |

| Muscle/joint pain | 2,287 (19.5%) | 372 (10.8%) | 1.80 (1.63-2.00) | 1.42 (1.27-1.59) | 283 (22.5%) | 2.61 (1.59-4.27) |

| Sneezing | 729 (6.2%) | 120 (3.5%) | 1.78 (1.47-2.15) | 1.60 (1.31-1.97) | 73 (5.8%) | 2.52 (0.93-6.81) |

| Chest pain | 589 (5.0%) | 99 (2.9%) | 1.74 (1.41-2.15) | 1.07 (0.84-1.37) | 54 (4.3%) | 3.73 (0.92-15.16) |

| Conjunctivitis | 91 (0.8%) | 19 (0.6%) | 1.40 (0.86-2.30) | 1.10 (0.63-1.93) | 12 (1.0%) | N/A |

| Nasal congestion | 2,456 (21.0%) | 559 (16.3%) | 1.29 (1.18-1.40) | 1.11 (1.01-1.22) | 327 (23.0%) | 1.96 (1.33-2.91) |

| Rhinorrhea | 2,525 (21.6%) | 637 (18.6%) | 1.16 (1.07-1.26) | 1.03 (0.94-1.13 | 308 (24.4%) | 1.37 (0.98-1.92) |

| Dyspnea | 1,349 (11.5%) | 379 (11.0%) | 1.04 (0.94-1.16) | 0.67 (0.59-0.76) | 120 (9.5%) | 2.37 (1.12-4.99) |

| Cough | 5,683 (48.6%) | 1,642 (47.9%) | 1.01 (0.98-1.06) | 0.83 (0.79-0.87) | 622 (49.4%) | 1.87 (1.45-2.41) |

| Sore throat | 3,222 (27.5%) | 1,359 (39.6%) | 0.69 (0.66-0.73) | 0.58 (0.55-0.62) | 386 (30.6%) | 0.86 (0.69-1.07) |

| Asymptomaticc | 1,826 (15.6%) | 911 (26.6%) | 0.59 (0.55, 0.63) | 0.98 (0.91, 1.05) | 175 (13.9%) | 0.45 (0.34, 0.58) |

CDOM = Communicable Disease Outbreak Management; N/A ;= not applicable; SARS-CoV2 = severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2.

Malaise, general feeling of discomfort or not feeling well.

Fatigue, tiredness.

Asymptomatic, answered no to all questions on the standardized symptom questionnaire and did not report any other symptoms in the free-text field.

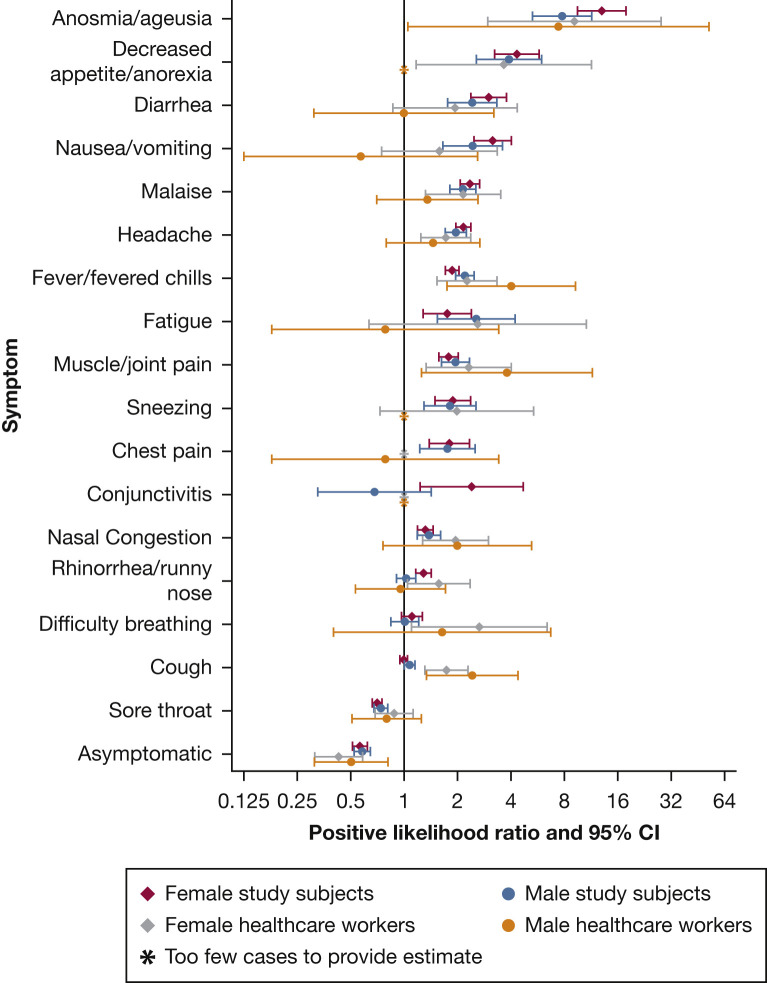

PLRs were similar in men and women (Fig 1 ), in the sensitivity analysis restricted to the 9,153 individuals who were swabbed for high-risk contact tracing (5,723 of whom were positive for SARS-CoV-2), and in health-care workers (Table 1). We also found that individuals with swab tests positive for SARS-CoV-2 were more likely to be men, older, current smokers of cigarettes or cannabis, or users of vaping products (Table 1).

Figure 1.

Positive likelihood ratio for severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 infection for each symptom in the tested adult population and in health-care workers, stratified by sex.

Discussion

In adult outpatients, we found that upper respiratory tract symptoms were less predictive of SARS-CoV-2 infection than anosmia/ageusia or decreased appetite (which were the only symptoms that appreciably altered the likelihood of a patient having a positive swab result). Symptom patterns and PLRs were similar in health-care workers. Although the frequency of some symptoms in our cohort were lower than reported in prior studies,1 , 3, 4, 5, 6, 7, 8 that is not surprising because most of those studies included only hospitalized patients and were retrospective. Although many prior studies did not systematically collect data on anosmia/ageusia, our results confirm reports that examined free text of smartphone app entries or telehealth visit interactions and found that the words “taste,” “sense,” and “lost” were used with much higher frequency by patients infected with SARS-CoV-2 than those who tested negative, with an OR of 6.7 for test positivity.3 , 8

Despite our large sample size and symptom information from adults who tested positive or negative for SARS-CoV-2, our study does have some limitations. For one, the standardized questionnaire did not include anosmia/ageusia until August 15; before then, we had to extract that symptom from the free text area of the questionnaire where patients could report any other symptoms without prompting. The fact that anosmia/ageusia had the largest PLR of all symptoms both before and after August 15 is reassuring, but the frequency would undoubtedly have been higher if anosmia/ageusia had been included in the standard questionnaire from the start or if odorant exposure tests had been used (a European study4 reported loss of smell in 87% of patients with COVID-19 and loss of taste in 56%). Second, there is some potential for misclassification of SARS-CoV-2 status given the less than 100% sensitivity and specificity of RT-PCR testing for SARS-CoV-29; however, any misclassification is likely to have biased toward the null and reduced the strength of our reported associations between symptoms and swab positivity. Third, we do not have symptom data from all patients who had a negative RT-PCR swab result in Alberta, as the CDOM database included only negative patients who were being contact traced. Although this could potentially distort underlying population frequencies and findings, the fact that the PLRs for the sensitivity analysis restricted to high-risk contacts were similar to those from the main analysis provides reassurance that the associations we found between symptoms and SARS-CoV-2 positivity were not unduly influenced by CDOM eligibility criteria. Fourth, it is unknown if the symptoms associated with SARS-CoV-2 infection will change with seasonality.

Nevertheless, we were able to define those symptoms that were most strongly associated with SARS-CoV-2 infection in adult outpatients and in health-care workers in an entire Canadian province. Employers or educational institutions using Fitness to Work symptom questionnaires to screen adults should consider revising their standardized questions accordingly.

Acknowledgments

Author contributions: F. A. M. conceived and designed the study and wrote the manuscript; he is the guarantor for the work. T. A. W. and J. A. K. collected and analyzed the data under the supervision of J. A. B. All authors revised the manuscript.

Other contributions: The authors thank Tanya Masson-McCrory, MHS, Clinical Educator for the Alberta Health Services Communicable Disease Outbreak Management (CDOM) program, and the medical student volunteers who helped collect symptom data from patients included in the CDOM. The interpretation and conclusions contained herein are those of the researchers and do not represent the views of the government of Alberta or Alberta Health Services. Neither the government of Alberta nor Alberta Health Services express any opinion in relation to this study.

Footnotes

FINANCIAL/NONFINANCIAL DISCLOSURES: The authors have reported to CHEST the following: F. A. M. is funded by an Alberta Health Services Chair in Cardiovascular Outcomes Research, and this project was supported by the Alberta Strategy for Patient-Oriented Research Support Unit. This study is based in part on data provided by Alberta Health and Alberta Health Services. None declared (T. A. W., J. A. K., J. A. B.).

References

- 1.Wynants L., Van Calster B., Collins G.S. Prediction models for diagnosis and prognosis of covid-19 infection: systematic review and critical appraisal. BMJ. 2020;369:m1328. doi: 10.1136/bmj.m1328. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.McGee S. Simplifying likelihood ratios. J Gen Intern Med. 2002;17(8):646–649. doi: 10.1046/j.1525-1497.2002.10750.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Menni C., Valdes A.M., Freidin M.B. Real-time tracking of self-reported symptoms to predict potential COVID-19. Nat Med. 2020;26(7):1037–1040. doi: 10.1038/s41591-020-0916-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Lechien J.R., Chiesa-Estomba C.M., Hans S., Barillari M.R., Jouffe L., Saussez S. Loss of smell and taste in 2013 European patients with mild to moderate COVID-19. Ann Intern Med. 2020;173(8):672–675. doi: 10.7326/M20-2428. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Sedaghat A.R., Gengler I., Speth M.M. Olfactory dysfunction: a highly prevalent symptom of COVID-19 with public health significance. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2020;163(1):12–15. doi: 10.1177/0194599820926464. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Wee L.E., Chan Y.F.Z., Teo N.W.Y. The role of self-reported olfactory and gustatory dysfunction as a screening criterion for suspected COVID-19. Eur Arch Otorhinolaryngol. 2020;277(8):2389–2390. doi: 10.1007/s00405-020-05999-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Beltrán-Corbellini Á., Chico-García J.L., Martínez-Poles J. Acute-onset smell and taste disorders in the context of COVID-19: a pilot multicentre polymerase chain reaction based case-control study. Eur J Neurol. 2020;27(9):1738–1741. doi: 10.1111/ene.14273. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Obeid J.S., Davis M., Turner M. An artificial intelligence approach to COVID-19 infection risk assessment in virtual visits: a case report. J Am Med Inform Assoc. 2020;27(8):1321–1325. doi: 10.1093/jamia/ocaa105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Wang W., Xu Y., Gao R. Detection of SARS-CoV-2 in different types of clinical specimens. JAMA. 2020;323(18):1843–1844. doi: 10.1001/jama.2020.3786. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]