Abstract

The COVID-19 pandemic illustrates the importance of treatment-related decision making in populations. This article considers the case where the transmission rate of the disease as well as the efficiency of treatments is subject to uncertainty. We consider two different regimes, or submodels, of the stochastic SIR model, where the population consists of three groups: susceptible, infected and recovered and dead. In the first regime the proportion of infected is very low, and the proportion of susceptible is very close to 100the proportion of infected is moderate, but not negligible. We show that the first regime corresponds almost exactly to a well-known problem in finance, the problem of portfolio and consumption decisions under mean-reverting returns (Wachter, JFQA 2002), for which the optimal control has an analytical solution. We develop a perturbative solution for the second problem. To our knowledge, this paper represents one of the first attempts to develop analytical/perturbative solutions, as opposed to numerical solutions to stochastic SIR models.

Keywords: SIR model, COVID-19, SARS-CoV-2, Epidemics, Stochastic optimal control

1. Introduction

In December 2019, a novel coronavirus later named severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2) emerged in Wuhan, China, and during January and mid-March 2020 spread rapidly from its epicenter to other Chinese cities and to over 150 countries across all continents [1], [2]. On March 11 2020, the World Health Organization (WHO) declared COVID-19, the disease caused by SARS-CoV2, a pandemic [3]; six months after its emergence, the number of confirmed cases of COVID-19 globally exceeded 10 million, with over 500,000 deaths [1]. The pandemic has strained public health and medical systems internationally, caused global economic activity to stagnate, and disrupted normal patterns of life across societies [4], [5].

Epidemiologically, the rapid and explosive proliferation of SARS-CoV2 infection following its introduction to human populations is due the lack of pre-existing immunity to the new virus [6], [7]. SARS-CoV2 transmission primarily occurs through person-to-person contact when a person with COVID-19 coughs, sneezes or talks producing respiratory droplets containing the virus which reach the nose or mouth of another person in close proximity allowing for their inhalation [8]. Persons infected with SARS-CoV2 experience a wide range of clinical manifestations of illness, from asymptomatic to severe disease [9], [10]. While treatment guidelines recommend that patients with mild to moderate disease self-manage and monitor their illness at home and/or receive appropriate care to relieve symptoms, a proportion of patients with severe COVID-19 will seek medical attention and require hospitalization [11]. In the United States, in-patient care for COVID-19 currently involves supportive management of common complications of severe disease, as no specific FDA-approved drug is available to treat COVID-19 to date. A number of therapeutic options of unknown safety and efficacy are currently under investigation for COVID-19 and are being administered to hospitalized patients. As is true for the management of other diseases, the decision to treat COVID-19 involves the patient, their family and their health care provider, and weighs the potential benefits and risks of available treatment options. Until one or more vaccine is developed for COVID-19, drugs that shorten the infectious period and reduce transmission of SARS-CoV2 can contribute to controlling the epidemic within the population in addition to reducing morbidity and mortality in severely ill patients [12], [13], [14], [15].

Mathematical models have long been used in infectious disease epidemiology for understanding the dynamics of epidemics in populations and predicting outcomes of effective control strategies [16], [17], [18], [19]. In the classic SIR model, one of the most commonly implemented and the basis for other models, persons within a population move between three compartments, “Susceptible”, “Infected”, and “Recovered” as a pathogen spreads from person to person [20], [21]. Stochastic modeling approaches are important when there is uncertainty in model parameters as would be associated with variability in population demographics that can impact epidemic outcomes [22]. Here we use a simplified version of the stochastic SIRV (“V”: “Vaccinated”) model developed by Ishikawa [23] to examine the effect of implementing treatments of uncertain efficacy to control the COVID-19 epidemic. Whereas authors like Ishikawa implement a numerical method to determine the optimal control, our goal in simplifying his model was to obtain tractable solutions, either analytical or perturbative. There are two main methods in stochastic control: the maximum principle, and stochastic dynamic programming (DP). In epidemiology, the deterministic version of Pontryagin’s maximum principle was used for instance by Bolzoni et al. [24]. Ishikawa [23] used stochastic DP. Among others, Cox and Huang [25] pioneered the martingale approach as an alternative to stochastic DP. Roughly speaking, in stochastic DP one attempts to first determine the optimal control and then the optimal state dynamics. In the martingale approach, the order is reversed. We found it easier to use the martingale approach. In the low infection case, we show that our model is very similar to the financial model considered by Wachter [26], who uses the martingale approach. The same problem was generalized by Liu [27], who uses stochastic DP.

The main novelty of this article is to determine the optimal control in presence of uncertainty on the treatment recovery rate. We incorporate two forms of uncertainty in our model: (i) uncertainty on the contemporaneous value of the treatment recovery rate (which we will succinctly call treatment measurement error) and (ii) uncertainty on the future value of the treatment recovery rate.

We will consider two regimes of our SIR model. In the first regime the proportion of infected is very low, and the proportion of susceptible is very close to 100%. This corresponds to a disease with few cases and deaths, and where recovered individuals do not acquire immunity. In a second regime, the proportion of infected is moderate, but not negligible. The main new mathematical result of this article is to develop a perturbative solution for the second regime. Remarkably, both regimes (in a first approximation) have the same optimal control policy, which is independent of both the proportion of infected and the proportion of susceptible. On a second approximation, the optimal policy in the second regime is influenced by the latter variables.

Another contribution of this paper is to import from finance to the epidemiologic literature two different measures which combine the expected recovery rate of treatment as well as its dispersion. The first one, the Sharpe ratio, is appropriate when only a single treatment is available. The second one, the beta of the treatment, extends this concept to multiple treatments. Indeed, some treatments taken together can have synergistic effects either in their mean and their dispersion of the combined recovery rate (positive correlation of the recovery rates), or both, or can have antagonistic effects in their dispersion of the combined recovery rate (negative correlation).

The structure of the article is as follows: Section 2 introduces the stochastic SIR model with treatment uncertainty. In Section 3 we present our results, both theoretical and numerical for the regime of low proportion of infected. In Section 4 we present our results for the regime of moderate proportion of infected. We briefly allude to the general case in our conclusion. We present in Section 5 an application to COVID-19. The proof of our main result, Proposition 2, is in Appendix.

2. A stochastic SIR model with treatment uncertainty

Notation

Let be the proportion of susceptible, infected, recovered. Let be the transmission rate and be the death rate.

In the SIR model, the rate of decrease of the proportion of susceptible is equal to the constant transmission rate time . In a stochastic model this remains true on average, that is,

We complete this model by adding a noise term , where is white noise. This is a simplified version of the model in Ishikawa [23]:

| (1) |

Our noise term is such that, as required, remains in the interval . Indeed, when , the rate is clearly zero, while when , we have , thus is also equal to zero.

For simplicity, we label the “no treatment case” by the subscript , and the “treatment case” by the subscript . We call ( ) the recovery rate of treatment and () the death rate. In Section 3.2 we will generalize this model to the multiple treatment case, so that treatments recovery rates will be labeled for .

The optimal policy is referred to as the optimal allocation of the treatment. The product corresponds to the proportion of the population that recovers due to the treatment in period . The allocation can have two different interpretations. In the first one represents the proportion of infected that undergo treatment, and thus . In the second interpretation, we assume (like in the AIDS epidemic) that treatment is very expensive, and that recovery depends linearly (in a first approximation) on how much one spends on the treatment. In this case corresponds then to the recovery rate of the basic dose of the treatment, while corresponds to how many doses the population purchases. The situation corresponds to the case where treatment is discovered to become harmful and necessitates an alternative treatment. For simplicity, we will describe our model as a function of the first interpretation thereafter but relax the constraint .1

Depending whether the individual is treated or not, there are then four different ways for an infected individual to exit the pool of infected:

-

•

not treated and recover

-

•

not treated and die

-

•

treated and recover

-

•

treated and die

Thus, the “out of infection rate” will be:

| (2) |

For simplicity, we assume that the Brownian motion driving transmission uncertainty () is independent from the Brownian motion driving treatment uncertainty (). We suppose that (people die faster without treatment than with treatment), but the reader will not lose any intuition by supposing that . Most of the time (treatment is better than no treatment), but not necessarily. We relax this requirement somewhat by requiring:

| (3) |

We model the treatment rate as an Ornstein–Uhlenbeck process:

with the mean-reversion rate and the long run value of the treatment rate . It is well-known that is Gaussian, with variance equal to:

Thus, if mean-reversion is large compared to volatility , constraint (3) is satisfied. We simplify (2) by:

| (4) |

Putting everything together, the dynamics of the infected is:

We try to minimize a measure of the infected over our horizon . To model risk-aversion to unfavorable treatment decisions, the decision-maker (for instance, governmental biomedical and public health entities specifying treatment guidelines) is supposed to minimize the expected value of a convex and increasing function of . Alternately, one can maximize the negative thereof, i.e., maximize the expected value of a concave and decreasing function of . Such a function is called a utility function in financial economics. The policy obtained in maximizing the expected value of a concave utility function can be shown, under certain conditions, to maximize the expected value of the outcome (here ) under a constraint on the dispersion of the outcome. Out of the universe of concave decreasing utility functions, we choose the power utility function

The coefficient is often called the risk-aversion parameter. When , the decision-maker is risk-neutral, meaning that the uncertainty does not have an influence on her decisions. It is straightforward to check that this power utility function is concave in when ,which we will assume. Taking for instance , we see that the objective is to

which returns the same policy as:

The importance of analytic formulations is that other figures of interest in this model, like the expected number of deaths from treatment can be analytically calculated, and depend on . Thus, a decision-maker can calibrate its risk-aversion parameter on other goals. Expected number of deaths is only one type of goal and economic factors that can be easily added. Our controlled SIR model is thus:

| (5) |

| (6) |

Observation The relative sign of our volatilities and is important. We will assume without loss of generality that . The sign of is the sign of covariance between the measured value of today’s treatment rate and the change in value of the treatment rate between today and a future date. An example may help illustrate the difference. Suppose that over a week one performs daily measurements of the treatment recovery rate as well as daily forecasts of the evolution of the treatment recovery rate over the next day. The two quantities measured each day are proportional to the same white noise . One then calculates weekly estimates of and of over these 7 daily observations. Since we arbitrarily choose , a positive shows a correlation of +1 between the measurement (of today’s treatment rate) and the forecast.

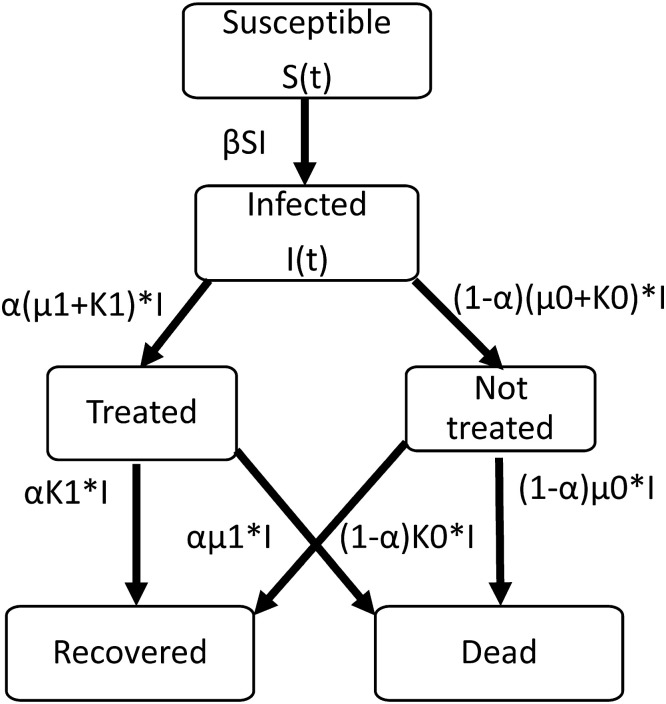

Fig. 1 is a depiction of our model.

Fig. 1.

A stochastic SIR Model.

3. Results in the low infection regime

3.1. Single treatment case

We assume close to one and . Thus the term:

is almost constant. We call the risk-free infection rate. Indeed treatment is risky but, on average has beneficial effects. We also define the impact of treatment risk :

| (7) |

as well as the long run impact of the treatment risk

| (8) |

Defining , , it is straightforward to see that is also an Ornstein–Uhlenbeck process, i.e. :

and condition (3) translates into:

In Appendix A we develop a comparison between our model and a model of optimal investment,

We restate our problem thus as:

| (9) |

| (10) |

| (11) |

In this regime our solution will depend on a kernel , while in the second regime it will also depend on two other kernels and that are closely related. In order to unify notation we define the kernels in a unique way.

Definition

the solution kernels for are given by:

(12)

For the kernel , we have:

| (13) |

| (14) |

| (15) |

where

Proposition 1

If then the problem (9) , (10) , (11) has a unique optimal solution given by:

(16) where

(17)

(18) Moreover the optimal allocation of the treatment is equal to

(19)

Sketch of Proof

For existence and uniqueness of the solution, we refer to Wachter [26]. The key point is to verify that given in (13) is finite, which occurs if . Whereas Wachter proved it in the case , in our case . We first rewrite as:

Recall that, since , . Thus, if :

Clearly, if , then , so that:

Thus show that is finite and thus differentiable. Clearly (14), (15) show that both and are finite and differentiable. Let the operator be defined by

The martingale method then results in the Ansatz where solves the PDE:

which solution is (16). ■

The advantage of this solution is the remarkably clear interpretation of (19). To borrow terminology from finance, the optimal is the sum of:

-

•

the myopic allocation

-

•

the hedging allocation .

As shown in [28], the myopic allocation is the optimal in a simpler model where the impact of treatment risk is constant, which means that, in our model the recovery rate is a constant . It coincides with the static allocation in a traditional mean–variance model of Markowitz [29]. Thus as expected, the myopic allocation can be decomposed into:

| (20) |

The Sharpe ratio of a security is a measure of its risk-adjusted return and characterizes the attractiveness of the security. Conversely in our model the Sharpe ratio characterizes the potential benefit of the treatment. The less uncertain the treatment ( small) the more the treatment should be recommended. Also, the higher the difference , i.e., the difference of recovery rates between treatment and no treatment, the more desirable the treatment. Eq. (20) also shows the importance of the term . The more risk-averse the decision maker , the less likely he or she is to opt for the risky treatment.

For a risk-neutral decision maker, . Thus the myopic solution is simple:

-

•

if : treat everybody

-

•

if : treat nobody.

We note that the same bang–bang solution obtains in the case of perfect knowledge of the treatment quality ().

Whereas the myopic allocation is a best response to treatment measurement error, the hedging allocation responds to the (future) stochastic behavior of the treatment. It is easy to see that both and decrease with time (in absolute value) and are equal to zero at the horizon . Moreover, is positive.

Thus the importance of the hedging allocation decreases with time. This is consistent with the meaning of hedging: hedging is important at the beginning of treatment, because its effects are felt over a long period, but when time is close to the horizon, its importance vanishes.

To get a better grasp of the hedging allocation, we rewrite it in two equivalent expressions. We replace by (7) and by (8) and write , where:

The first expression for the hedging allocation is then:

Suppose that is very small so that is negligible. In that case, the influence of is negligible. Then assuming treatment is beneficial (both larger than , and ) the hedging allocation is:

-

•

positive if

-

•

negative otherwise.

This policy above is consistent with the meaning of hedging. Suppose that today’s measurements are negatively correlated with the forecast of the recovery rate, i.e., , then the hedging allocation should be positive in anticipation of better treatment performance to come. Conversely, the hedging allocation should be negative when the forecast is worse than the measurement. To highlight the importance of the long run value of the treatment when is larger, we use our second expression for the hedging allocation:

| (21) |

| (22) |

| (23) |

Consider the case when treatment improves with time, i.e., when . There are now two subcases. If has the opposite sign as , then the hedging allocation increases with , in anticipation of even better results to come. Conversely, if has the same sign as , then the hedging allocation decreases with .

Like for the myopic allocation, the absolute value of the hedging allocation is inversely proportional to . The higher the risk aversion ( high) or the higher the imprecision ( high), the smaller should be the magnitude of the hedging allocation.

Finally, it is remarkable that the value of has no impact on the optimal treatment policy.

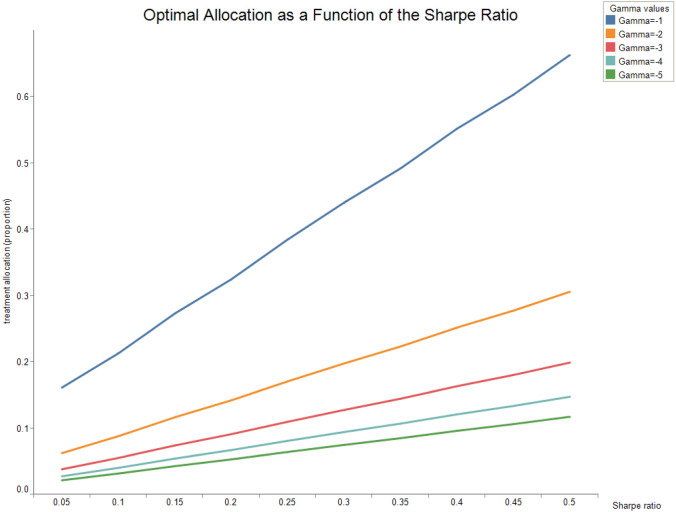

The following figures show how the optimal allocation varies as a function of the risk-aversion parameter . Fig. 2 shows the optimal allocation as a function of the Sharpe ratio for horizon months at time .

Fig. 2.

Parameters are , , , , , .

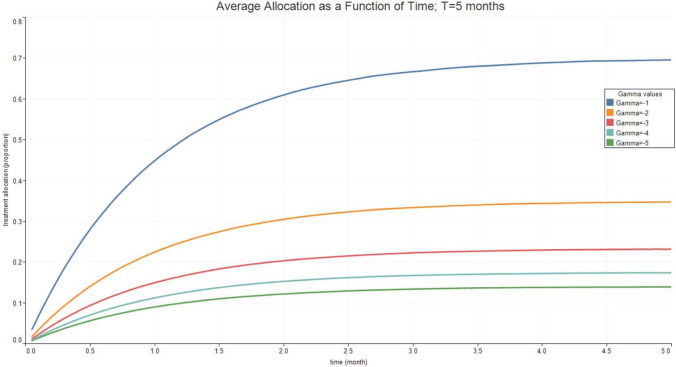

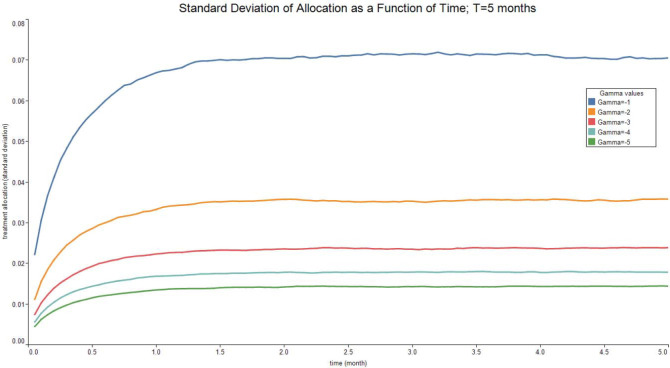

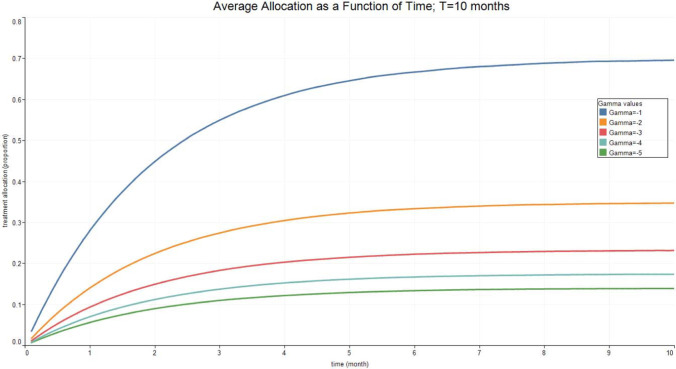

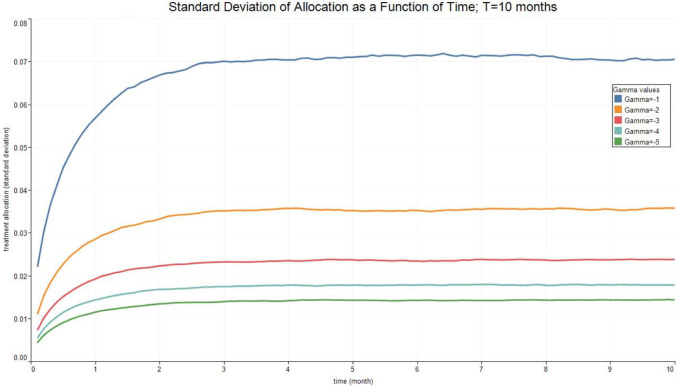

Fig. 3, Fig. 4, Fig. 5, Fig. 6 report the expected valued and the standard deviation of the optimal allocation as a function of time. As can be seen, since is Gaussian, it is easy to reduce the probability that is outside the interval : one needs only select a lower . The parameters for the four cases below are given in Table 1. We assume that time is measured in months.

Fig. 3.

Optimal Allocation. See Table 1 for parameter values.

Fig. 4.

Optimal Allocation. See Table 1 for parameter values.

Fig. 5.

Optimal Allocation. See Table 1 for parameter values.

Fig. 6.

Optimal Allocation. See Table 1 for parameter values.

Table 1.

| Treatment parameter | Symbol | Value |

|---|---|---|

| Death rate/no treatment | 0.1 | |

| Death rate | 0.1 | |

| Recovery rate/ no treatment | 1.8 | |

| Recovery rate at time 0 | 1.8 | |

| Long run value of recovery rate | 2.5 | |

| Volatility of the measurement of today’s recovery rate | 1 | |

| Volatility of changes in the recovery rate | 0.1 | |

| Speed of mean-reversion of the recovery rate | 1 |

3.2. Multiple treatment case

Generalizing the model above to multiple treatments poses considerable technical difficulties. We refer the reader to Liu (2007) for a discussion. We consider instead in this section a useful simplification of the model. While the impact of each treatment is imprecise, each treatment recovery rate is constant, i.e.:

The allocation , which as explained above can represent the proportion of the infected undergoing treatment satisfies:

We suppose a normal model, whereby that the covariance between the treatment recovery rates and over a period of time equal to is given by . Let be a square root of the variance–covariance matrix . The equation for the out-of infection rate (4) can thus be generalized into:

| (24) |

where are independent Brownian motions. The resulting problem is identical to the Merton [28] portfolio problem. We define the following vectors. Let be the allocation, be the treatment recovery rate, be the death rate of each treatment, and be the vector of ones. Then the optimal allocation is:

The attentive reader will realize that this is a multivariate generalization of the myopic allocation (20). While a good measure of the efficiency of the treatment is the Sharpe ratio in the single treatment case, we suggest that, for multiple treatments, a good measure to compare treatments would be the beta of each treatment recovery rate, especially if the number of treatments is large. The beta of a security is one of the main measures to pick stocks in a financial portfolio. In addition to the Sharpe ratio, the beta includes the correlation between the recovery rate of a single treatment and the recovery rate of a combination of optimal treatments. Since space is lacking to define beta properly, we refer the reader to a financial textbook such as Ingersoll [30].

4. Results in the moderate infection regime

For simplicity, we write:

We restate our problem thus as:

| (25) |

| (26) |

| (27) |

| (28) |

| (29) |

Our solutions are also written as a function of the kernels defined by the formula (12). For the first kernel , we have:

| (30) |

| (31) |

| (32) |

The second kernel , is obtained by replacing by in the first kernel, that is:

| (33) |

| (34) |

| (35) |

where

Proposition 2

Let . If then the problem (25) to (29) has a solution such that

(36)

where satisfies:

(37)

Moreover the optimal proportion undergoing treatment is equal to , where is given in (19) :

Observation: It is remarkable that, as a first order approximation, the optimal policy is the same in the low and moderate pandemic regimes. The term can be easily calculated by inserting (36) into (68). Both and have a non-negligible impact on . We leave a more detailed analysis for future work.

5. Application to COVID-19

In this section, we assume a low infection regime. We calculated the optimal control and infected for two experiments:

-

•

experiment 1: US data set in 2020 with long run value of the recovery rate () estimated from the data

-

•

experiment 2: US data set in 2020 with improved long run value of the recovery rate ().

The reason for considering the second dataset is clear, after observing the results. The value of estimated from the data was very low, barely better than the no treatment recovery rate (). With a constant value of , the pandemic goes beyond control, and the low infection regime assumption does not hold any more, yielding absurd results. Multiplying by a factor 10 makes us stay in the low infection regime in experiment 2.

Results in Section 3 show that for the probability that is significant. For this reason, we used lower values of in this section.

In both experiments, we performed a Monte Carlo simulation using the Euler scheme and 10,000 scenarios, starting at , or about 1 million persons in the US.

5.1. Experiment 1: US DataSet in 2020

We calibrated our low infection regime model to weekly US Covid-19 data from April 12, 2020 to November 8, 2020. To simulate our model for the US population, we used publicly available data from the CDC [31] and the COVID Tracking Project [32] on COVID-19 cases and deaths by state over time for the period 4/12/20–11/8/20, mortality estimates from the Coronavirus Resource Center at Johns Hopkins University [33] and US Census data [34] to estimate the 2020 US population (i.e., denominator data). We supplemented these data with results from published studies of treated hospitalized COVID-19 patients [35], [36], [37], [38], statistics provided by the CDC for the purpose of COVID-19 pandemic planning [39], and referenced NIH COVID-19 Treatment Guidelines [40].

We assumed that there was no treatment before May 30, 2020, and an average treatment rate of 25% afterwards. The number of recovered in the period before May 30 was used to estimate . The transmission rate was assumed to be constant over the period. Likewise, since the treatment did not show consistent benefit on reducing deaths for patients with COVID-19, we set and chose the whole period to estimate it.

Taking the logarithm of the series and applying proper differencing, we obtained an ARMA(1,1) model for the period after May 30, 2020, which we estimated using the Econometric Toolbox in Matlab, which gave us all the other parameters. We set .

We obtained the following parameters shown in Table 2.

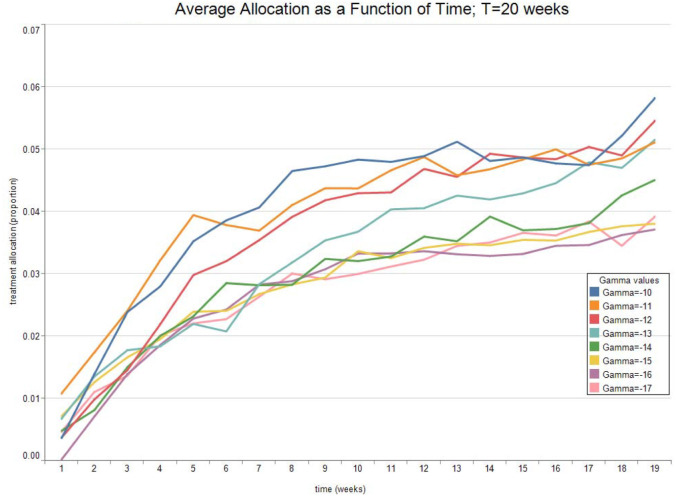

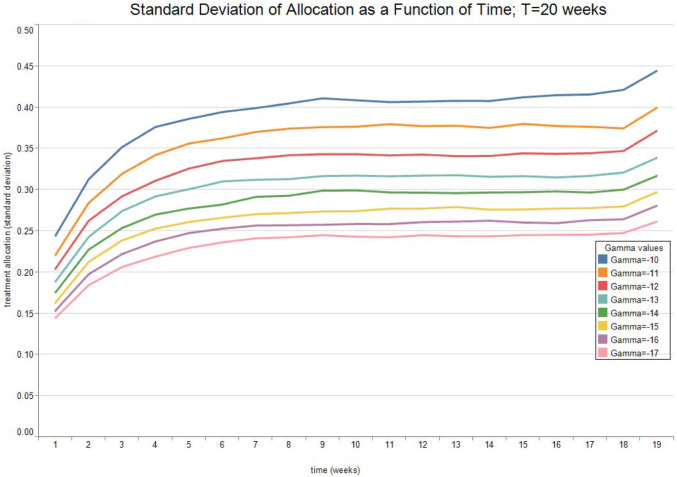

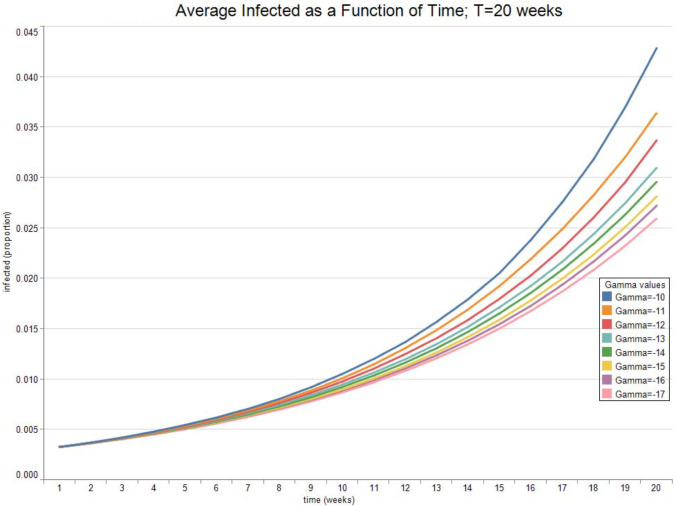

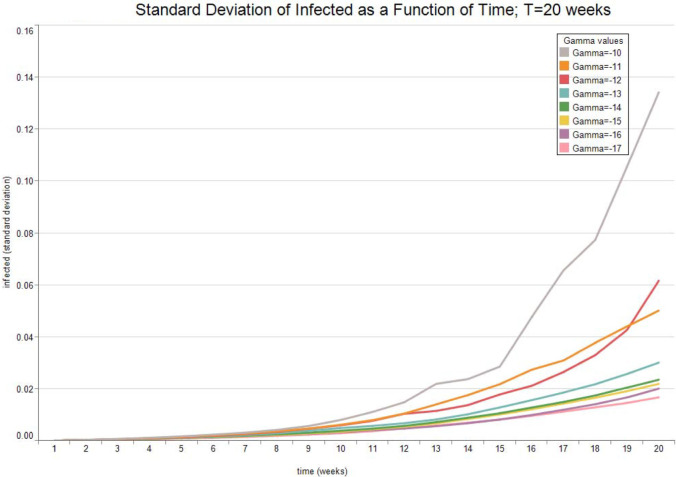

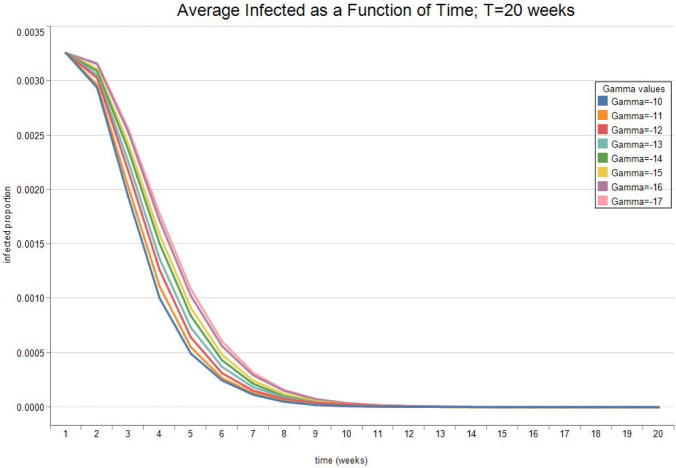

Fig. 7, Fig. 8 show the expected value and the standard deviation of the optimal allocation as a function of time. As before, a lower reduces the dispersion of as well as its mean. The optimal control increases with time on average, since the average recovery rate increases with time. However, Fig. 9, Fig. 10 show that after about-15 10 weeks the pandemic leaves the low infection regime. Results are then absurd,2 and are showed only for the sake of completeness.

Table 2.

| Treatment parameter | Symbol | Value |

|---|---|---|

| Death rate/no treatment | 0.0575 | |

| Death rate | 0.0575 | |

| Recovery rate/ no treatment | 0.2559 | |

| Recovery rate at time 0 | 0.2559 | |

| Long run value of recovery rate | 0.4612 | |

| Volatility of the measurement of today’s recovery rate | −0.4418 | |

| Volatility of changes in the recovery rate | −1.6623 | |

| Speed of mean-reversion of the recovery rate | 0.7692 |

Fig. 7.

Optimal Allocation. See Table 2 for parameter values.

Fig. 8.

Optimal Allocation. See Table 2 for parameter values.

Fig. 9.

Optimal Infected. See Table 2 for parameter values.

Fig. 10.

Optimal Infected. See Table 2 for parameter values.

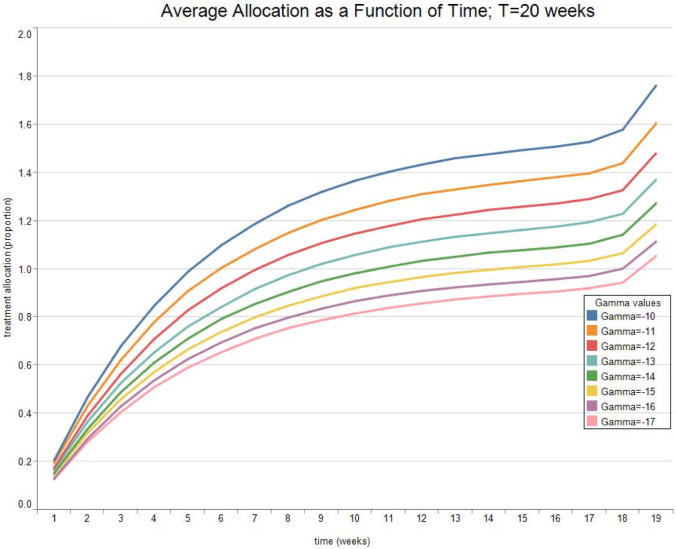

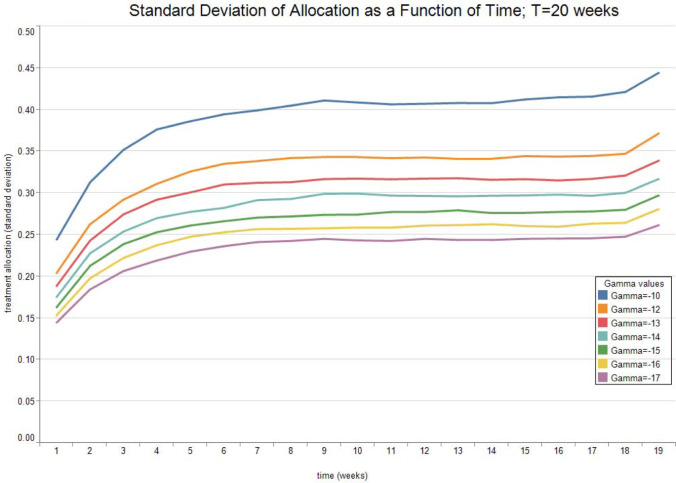

5.2. Experiment 2: US DataSet in 2020 with improved Treatment

We took the same parameters as in experiment 1, except for .

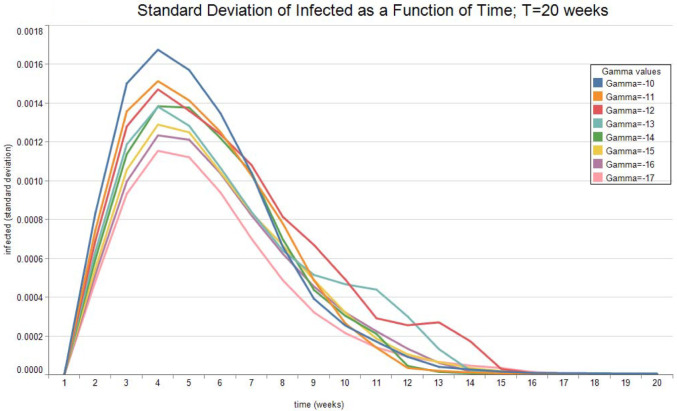

Fig. 10, Fig. 11 show the expected value and the standard deviation of the optimal allocation as a function of time. As before, a lower reduces the dispersion of as well as its mean. The optimal control increases with time on average, since the average recovery rate increases with time. Compared to experiment 2, the long run value of the recovery rate is sufficient to keep the epidemic in check, and the allocation is larger, since the treatment is better. The results are relatively insensitive to the value of , for . For higher values of , the optimal allocation is often larger than 1.

Table 3.

| Treatment parameter | Symbol | Value |

|---|---|---|

| Death rate/no treatment | 0.0575 | |

| Death rate | 0.0575 | |

| Recovery rate/ no treatment | 0.2559 | |

| Recovery rate at time 0 | 0.2559 | |

| Long run value of recovery rate | 4 | |

| Volatility of the measurement of today’s recovery rate | −0.4418 | |

| Volatility of changes in the recovery rate | −1.6623 | |

| Speed of mean-reversion of the recovery rate | 0.7692 |

Fig. 11.

Optimal Allocation. See Table 3 for parameter values.

6. Conclusion

We obtained in this paper a series of analytical expressions for the optimal proportion of infected undergoing treatment in a pandemic. We analyzed the low infection regime, where the pandemic statistics and dynamics do not have an impact. We then analyzed the moderate infection regime, where pandemic statistics and dynamics have a second order impact on the optimal decision. The main technical result of this article is Proposition 2. It is indeed remarkable that, while the SIR model with treatment uncertainty has no clear analytical solution that we know of, the optimal policy is tractable.

Many important problems remain to be solved. The first one consists in delimiting the frontier between the moderate infection and the high infection regimes. The solution technique used from Proposition 2 can be expanded to higher orders, but one needs to verify whether the solution is meaningful, i.e., if remains between zero and one. If not, then we reach the catastrophic high infection regime. Separating the differential operator acting on into two differential operators and (see (53), (54)) is qualitatively important. While the operator is a traditional semilinear parabolic operator, the operator is a quasilinear operator that resembles the operator in the nonlinear traffic equation. We may thus expect the catastrophe to arise from a shock wave, which would dominate the diffusive effects.

The multiple treatment situation deserves further attention. Indeed, our analysis in this article was restricted to the low infection regime with no uncertainty over the evolution of the treatment recovery rate. One should generalize our solution technique to the moderate infection regime, and possibly consider uncertainty over the forecast of the recovery rate.

Finally, we believe that the martingale approach of optimal control can be fruitfully applied to analytically characterize optimal vaccination schemes.

Funding

This research did not receive any specific grant from funding agencies in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

CRediT authorship contribution statement

Nicole M. Gatto: Conceptualization, Methodology, Writing -original draft, Writing - review and editing, Visualization. Henry Schellhorn: Conceptualization, Methodology, Software, Formal Analysis, Writing - original draft, Writing - review & editing, Visualization.

Declaration of Competing Interest

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

Acknowledgments

We thank Yujia Ding for proofreading some of our calculations in the COVID-19 model estimation. All remaining errors are ours.

Footnotes

We will see in the results section that, since follows an Ornstein–Uhlenbeck process, the probability that can be made very small, so that, even in the first interpretation, our control is quasi-optimal.

Another reason why our simple estimation does not reflect reality is that we assumed a constant value of over the period. Adoption of measures of social distancing as well as greater proportion of the population spending time outdoors resulted in a decrease of over the summer 2020, and a flattening of the epidemic.

Appendix A. Relation with the financial investment problem

The following table maps out the correspondence in variable names between the investment problem considered by Wachter [26] and our controlled stochastic SIR model.

| Consumption/investment model | Controlled stochastic SIR model |

|---|---|

| Wealth maximize | Infected : minimize |

| Risk-free interest rate | Risk-free infection rate |

| Risky asset allocation | Proportion undergoing risky treatment |

| Price of market risk (usually ) | Impact of treatment risk (usually ) |

| Risk aversion coefficient | Risk aversion coefficient |

Appendix B. Proof or Proposition 2

We introduce two Radon–Nikodym derivatives and :

By Girsanov theorem, the measure defined by:

for all in the filtration generated by is such that:

| (38) |

| (39) |

are -Brownian motions. We defined a stochastic process such that becomes a -martingale, with:

By Ito’s lemma:

| (40) |

Observe that is also a -martingale. Defining the Lagrange multipliers and , the martingale method consist in first solving the following problem:

Since the last term does not contain , the optimal satisfies . For convenience, we introduce a process , thus

| (41) |

By Ito’s lemma, the SDE (37) for obtains. Since is a -martingale, and since are sufficient statistics for the filtration

| (42) |

This, we posit a function such that the optimal satisfies:

While is not a - martingale, the process defined defined by:

| (43) |

is a - martingale. Indeed:

| (44) |

By Ito’s lemma applied to (43), we see that:

| (45) |

Comparing (27), (45), we see that:

| (46) |

| (47) |

Thus (27) becomes:

| (48) |

Since , substituting (38), (39) in (48) results in:

| (49) |

Dividing (46) by , we obtain:

This relation will allow us to replace all the partial derivatives with respect to by derivatives with respect to :

With these substitutions, the Dynkin operator defined by can thus be rewritten:

| (50) |

| (51) |

We can thus rewrite (49) as:

| (52) |

We do a perturbation expansion of (52) to the second order by defining two operators: , which does not contain terms and , which does. The operator will be more important than the operator in a moderate pandemic regime, as we shall see below. Defining:

| (53) |

| (54) |

Thus (52) can be written

| (55) |

Writing , we will assume that will remain of order in . We define by:

| (56) |

Since is linear and are linear, equation (55) can be rewritten:

However is quadratic, thus , and (55) becomes:

| (57) |

Our asymptotic expansion consists in:

which we insert in (57) to find:

The first two terms of our asymptotic expansion are thus determined by:

| (58) |

| (59) |

Solution of (58)

Fig. 12.

Optimal Allocation. See Table 3 for parameter values.

Fig. 13.

Optimal Infected. See Table 3 for parameter values.

Recall the differential operator which we defined in order to characterize the solution of the low pandemic mode. We remark that:

Thus equation (58) has the same solution as Wachter [26], provided we do the substitution , and set . Since we obtain slightly different results for from Wachter, we provide details of our solution. We postulate that the solution to (58) is separable:

| (60) |

Substitution in (58) shows that solves:

| (61) |

where the operator is defined by:

Using the Ansatz (12), we can rewrite the LHS of (61) into:

Clearly all terms must be identically zero. The equation becomes:

The equation is:

The equation is:

which admit the solutions (30),(31),(32).

Solution of (59)

The second equation can be rewritten

| (62) |

| (63) |

| (64) |

The trick is to consider to be a linear operator applied not to a function but to a stochastic field:

We try the Ansatz:

| (65) |

By the same reasoning as before, the terms can be canceled out from (62) provided the terminal condition (41) holds:

Clearly, given by (12),(33),(34), (35) solves

| (66) |

Thus:

| (67) |

The optimal solution (36) results from assembling (56), (57), (65), and (67). The optimal policy is given by (47):

| (68) |

Fig. 14.

Optimal Infected. See Table 3 for parameter values.

References

- 1.Johns Hopkins University & Medicine, Coronavirus Resource Center, 2020 [cited 2020 2020]; Available from: https://coronavirus.jhu.edu/.

- 2.World Health Organization . 2020. Novel Coronavirus (2019-nCoV) Situation Reports. Available from: https://www.who.int/emergencies/diseases/novel-coronavirus-2019/situation-reports. [Google Scholar]

- 3.World Health Organization . 2020. Novel Coronavirus (2019-NCoV) Situation Report - 51. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Cooper M. 2020. Tracking the Impact of the Coronavirus on the U.S. in The New York Times. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Haleem A., Javaid M., Vaishya R. Effects of COVID 19 pandemic in daily life. Curr. Med. Res. Practice. 2020;10(2):78–79. doi: 10.1016/j.cmrp.2020.03.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Sette A., Crotty S. Pre-existing immunity to SARS-CoV-2: the knowns and unknowns. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 2020 doi: 10.1038/s41577-020-0389-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.di Mauro G., et al. SARS-Cov-2 infection: Response of human immune system and possible implications for the rapid test and treatment. Int. Immunopharmacol. 2020;84 doi: 10.1016/j.intimp.2020.106519. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, How COVID-19 Spreads [cited 2020 July 11]; Available from: https://www.cdc.gov/coronavirus/2019-ncov/prevent-getting-sick/how-covid-spreads.html.

- 9.Kimball .H.K., et al. 2020. Asymptomatic and Presymptomatic SARS-CoV-2 Infections in Residents of a Long-Term Care Skilled Nursing Facility — King County, Washington, 2020: MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep 69; pp. 377–381. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Z. Wu, J.M. McGoogan, Characteristics of and Important Lessons From the Coronavirus Disease 2019 (COVID-19) Outbreak in China: Summary of a Report of 72314 Cases From the Chinese Center for Disease Control and Prevention. LID - DOI: 10.1001/jama.2020.2648 [doi] FAU - Wu, Zunyou (1538-3598 (Electronic)). [DOI] [PubMed]

- 11.COVID-19 Treatment Guidelines Panel, Coronavirus Disease 2019 (COVID-19) Treatment Guidelines. N.I.o. Health. Editor, 2019.

- 12.J.A.-O. Beigel, et al. Remdesivir for the Treatment of Covid-19 - Preliminary Report. LID - DOI: 10.1056/NEJMoa2007764 [doi] LID - NEJMoa2007764 (1533-4406 (Electronic)).

- 13.J. Geleris, et al. Observational Study of Hydroxychloroquine in Hospitalized Patients with Covid-19 (1533-4406 (Electronic)). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 14.M.A.-O. Mahévas, et al. Clinical efficacy of hydroxychloroquine in patients with covid-19 pneumonia who require oxygen: observational comparative study using routine care data (1756-1833 (Electronic)). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 15.Wang Y., et al. Remdesivir in adults with severe COVID-19: a randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled, multicentre trial. Lancet. 2020;395(10236):1569–1578. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(20)31022-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.H. Heesterbeek, et al. Modeling infectious disease dynamics in the complex landscape of global health (1095-9203 (Electronic)). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 17.Kermack W.O., McKendrick A.G. Contributions to the mathematical theory of epidemics: IV. Analysis of experimental epidemics of the virus disease mouse ectromelia. J. Hyg. 1937;37(2):172–187. doi: 10.1017/s0022172400034902. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Awerbuch T. Evolution of mathematical models of epidemics. Ann. New York Acad. Sci. 1994;740(1):232–241. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.1994.tb19873.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Nelson K.E., Williams C.M. third ed. Jones and Bartlett Publishers, LLC; 2007. Infectious Disease Epidemiology: Theory and Practice. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hethcote H.W. The mathematics of infectious diseases. SIAM Rev. 2000;42(4):599–653. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Allen L.J.S. In: Mathematical Epidemiology. Brauer F., van den Driessche P., Wu J., editors. Springer Berlin Heidelberg; Berlin, Heidelberg: 2008. An introduction to stochastic epidemic models; pp. 81–130. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Allen L.J.S., Burgin A.M. Comparison of deterministic and stochastic SIS and SIR models in discrete time. Math. Biosci. 2000;163(1):1–33. doi: 10.1016/s0025-5564(99)00047-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.M. Ishikawa, Stochastic optimal control of an sir epidemic model with vaccination, in: Proceedings of the ISCIE International Symposium on Stochastic Systems Theory and its Applications. 2012. The ISCIE Symposium on Stochastic Systems Theory and Its Applications.

- 24.Bolzoni L., et al. Time-optimal control strategies in SIR epidemic models. Math. Biosci. 2017;292:86–96. doi: 10.1016/j.mbs.2017.07.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Cox J.C., Huang C.-f. Optimal consumption and portfolio policies when asset prices follow a diffusion process. J. Econom. Theory. 1989;49(1):33–83. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Wachter J.A. Portfolio and consumption decisions under mean-reverting returns: An exact solution for complete markets. J. Financial Quant. Anal. 2002:63–91. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Liu J. Portfolio selection in stochastic environments. Rev. Financ. Stud. 2007;20(1):1–39. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Merton R.C. An intertemporal capital asset pricing model. Econometrica. 1973:867–887. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Markowitz H. Portfolio selection*. J. Finance. 1952;7(1):77–91. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Ingersoll J.E. Rowman and Littlefield; 1987. Theory of Financial Decision Making. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention United States COVID-19 Cases and Deaths by State over Time. (Accessed 11 September 2020). Available from: https://data.cdc.gov/Case-Surveillance/United-States-COVID-19-Cases-and-Deaths-by-State-o/9mfq-cb36.

- 32.COVID Tracking Project at the Atlantic. (Accessed 11 September 2020). Available from: https://covidtracking.com/data.

- 33.Johns Hopkins University Coronavirus Resource Center. (Accessed 10 January 2020). Available from: https://coronavirus.jhu.edu/data/mortality.

- 34.United States Census Bureau Census data. (Accessed 10 January 2020). Available from: https://www.census.gov/topics/population.html.

- 35.Beigel J.H., Tomashek K.M., Dodd L.E., et al. Remdesivir for the treatment of COVID-19 - Final report. New Engl. J. Med. 2020 doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa2007764. Available at: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/32445440. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Wang Y., Zhang D., Du G., et al. Remdesivir in adults with severe COVID-19: a randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled, multicentre trial. Lancet. 2020;395(10236):1569–1578. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(20)31022-9. Available at: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/32423584. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Spinner C.D., Gottlieb R.L., Criner G.J., et al. Effect of remdesivir vs standard care on clinical status at 11 days in patients with moderate COVID-19: a randomized clinical trial. JAMA. 2020;324(11):1048–1057. doi: 10.1001/jama.2020.16349. Available at: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/32821939. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Goldman J.D., Lye D.C.B., Hui D.S., et al. Remdesivir for 5 or 10 days in patients with severe COVID-19. New Engl. J. Med. 2020 doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa2015301. Available at: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/32459919. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention COVID-19 Pandemic Planning Scenarios. Updated 9/10/20. Available at: https://www.cdc.gov/coronavirus/2019-ncov/hcp/planning-scenarios.html.

- 40.National Institutes of Health COVID-19 Treatment Guidelines. Updated 12/14/20. Available at: https://www.covid19treatmentguidelines.nih.gov/. [PubMed]