On January 30, 2020, the recent coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) pandemic, caused by the severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2), was declared as a Public Health Emergency of International Concern by the World Health Organization. On February 3, 2020, Brazil declared COVID-19 as a public health emergency and, up to date, became the World's 2nd country in cases accumulating altogether 1,539,081 cases and 63,174 deaths.1 During the recent outbreak of COVID-19, the Brazilian Indigenous people, a vulnerable group historically excluded from public policies, have suffered a disproportionate impact. Therefore, what are the main emergency challenges faced by Indigenous communities? How the absence of specific health care may affect this group during the current pandemic?

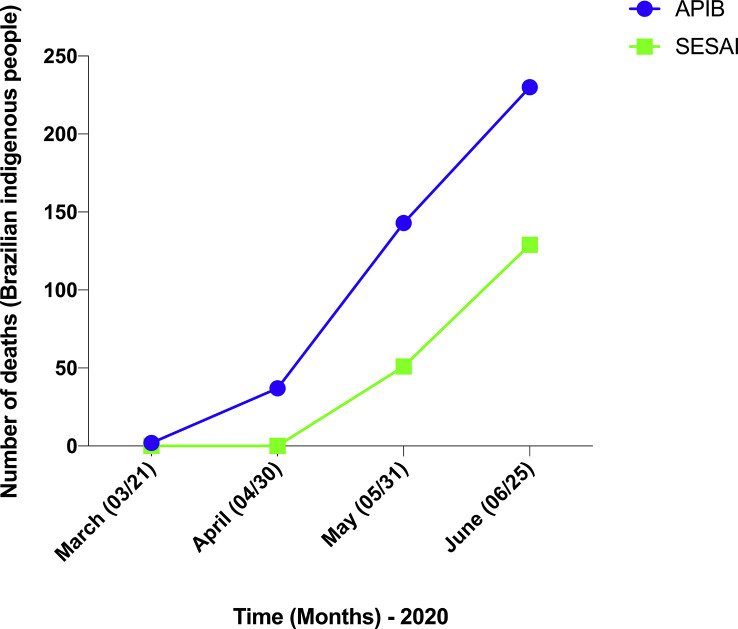

Regarding the current COVID-19 pandemic for Brazilian Indigenous people, the difficulty in determining the numbers of cases and deaths is one of the greatest challenges. Different levels of government, such as Special Secretary for Indigenous Health (SESAI) and State and Municipal Secretaries, have provided information on the dynamics of the reports but do not reflect the extent of the pandemic. To illustrate this, while the official reports disclosed by SESAI confirmed 5093 cases and 129 deaths on June 25, 2020, the Articulation of the Indigenous People of Brazil reported 8115 cases and 230 deaths2 , 3 (Fig. 1 ). The high rate of underreporting cases is mainly due to the lack of data on Indigenous people living outside homologated Indigenous lands, which are not taken into account by official figures, contributing to mask the reality faced by these people.

Fig. 1.

Differences between the number of deaths caused by the current severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2) in Brazilian Indigenous people disclosed by Special Secretary for Indigenous Health (SESAI) (government secretary) and Articulation of the Indigenous People of Brazil (APIB) (non-governmental) during the months of March (03/21/2020) to June (06/25/2020). The data were obtained from previous reports.2,3

As shown in Fig. 2 , the number of cases and deaths caused by the current coronavirus has shown an alarming rate in some states of the northern region of Brazil belonging to the Amazon region,1 a region marked by a flawed public health system. The rapid spread of this viral disease has threatened several Indigenous communities living in the Amazon region, including in the state of Amazonas. On April 6, 2020, the mayor of the state capital of Amazonas stated that the healthcare system collapsed, where public hospitals are no longer able to receive new patients infected with coronavirus.4 However, almost three months later, the number of new cases and deaths continues to increase substantially in the state.

Fig. 2.

Number of cases (A) and deaths (B) caused by SARS-CoV-2 in the states of Acre, Amazonas, Amapá, Pará and Roraima belonging to the northern region of Brazil during the months of March (03/31/2020) to June (06/25/2020). The data were obtained from ‘Brazilian Ministry of Health. Coronavirus Brazil’.1 SARS-CoV-2, severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2.

It is widely known that the limitation in face-to-face contact with others is the best way to reduce the spread of COVID-19. Therefore, on February 6, 2020, Brazil decreed the law (Nº 13.979) aiming the isolation between sick and infected individuals.5 However, most Indigenous tribes live in collective houses sharing utensils, such as bowls and other objects, which may favor the coronavirus transmission. Thus, health measures based on the physical isolation are a challenge for Indigenous people and basically not applicable.

Indigenous people are clearly a risk group for the severe COVID-19 outcomes due to the high rates of diabetes, malnutrition, tuberculosis, and other comorbidities, which may be a result of the lack of both an appropriate medical assistance and healthcare units to their communities.6 Indigenous tribes are more vulnerable to epidemics due to worse social, economic, and health conditions than non-indigenous people, which may amplify the potential for the spread of diseases. In addition, the greater immunological vulnerability of this group is an important factor that has contributed to decimate Indigenous communities by several diseases over the decades.7 The new pandemic is an unprecedented threat to Indigenous people, especially in the face of a federal government that has marginalized and neglected their rights, which are guaranteed by federal laws and international agreements.8

Brazil is a country marked by infrastructural weakness and economic/political instability, which deeply affect the public health system in promoting uniform medical assistance between different levels of society across the country. From an international perspective, despite the measures taken, the Brazilian government has failed to address the COVID-19 pandemic in any meaningful way. In this sense, the present Journal recently published an article that addresses this issue. Pereira et al.9 demonstrated that the current situation of subnormal clusters called favelas in Brazil in the face of coronavirus pandemic add another layer of complexity to the lack of sound public health reaction in the country.

To date, the situation of COVID-19 in Indigenous communities across the country is bleak. Brazil's government must take quick emergency measures to protect Indigenous people in the face of the new coronavirus pandemic to avoid a possible genocide. Thus, Brazil's government should create policies more specific to the Indigenous people, taken into account the peculiarities of these people, such as: (i) ensure isolation and monitoring in Indigenous areas; (ii) increase the number of health units with trained medical health professionals to deal specifically against to the pandemic; (iii) supply masks, gloves, hygiene products as alcohol for aseptic hands; (iv) offer wide access to water and food; (v) provide testing kits and emergency transport; and (vi) when possible, the immediate vaccination of Indigenous communities due to the greater immunological vulnerability. Taken together, the sad reality faced by Indigenous people in areas of social exclusion with a fragile health system is an emergency public health challenge for Brazil.

Funding

This study was supported by CNPq, CAPES, and FAPEMIG.

References

- 1.Brazilian Ministry of Health . July 04 2020. Coronavirus Brazil.https://covid.saude.gov.br Available from: [Google Scholar]

- 2.Plataforma de monitoramento da situação indígena na pandemia do novo coronavírus (Covid-19) no Brasil. Available from: https://covid19.socioambiental.org. July 04 2020.

- 3.Brazilian Ministry of Health . July 04 2020. Boletim Epidemiológico da SESAI.http://www.saudeindigena.net.br/coronavirus/mapaEp.php Available from: [Google Scholar]

- 4.Prefeito de Manaus afirma que saúde do AM entrou em colapso. Veja; 2020. https://veja.abril.com.br/brasil/prefeito-de-manaus-afirma-que-saude-do-am-entrou-em-colapso/ Available from: June 26, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Brasil. Lei No 13.979, de 6 de fevereiro de 2020 . July 5 2020. Dispõe sobre as medidas para enfrentamento da emergência de saúde pública de importância internacional decorrente do coronavírus responsável pelo surto de 2019.http://www.planalto.gov.br/ccivil_03/_ato2019-2022/2020/lei/L13979.htm Availabe from. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Guan W., Liang W., Zhao Y., Liang H., Chen Z., Li Y. Comorbidity and its impact on 1590 patients with COVID-19 in China: a nationwide analysis. Eur Respir J. 2020 doi: 10.1183/13993003.00547-2020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Pringle H. How Europeans brought sickness to the new World. Science. 2015 doi: 10.1126/science.aac6784. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ferrante M. Amazonian indigenous peoples are threatened by Brazil's Highway BR-319. Land Use Pol. 2020;94:104598. doi: 10.1016/j.landusepol.2020.104548. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Pereira R.J., do Nascimento G.N.L., Gratão L.H.A., Pimenta R.S. The risk of COVID-19 transmission in favelas and slums in Brazil. Publ Health. 2020;183:42–43. doi: 10.1016/j.puhe.2020.04.042. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]