Abstract

Introduction and objectives

Since the outbreak of the COVID-19 pandemic, increasing evidence suggests that infected patients present a high incidence of venous thromboembolic (VTE) events and elevated aminotransferases (AT).The objective of this work was to evaluate the incidence of aminotransferases disorders in patients infected with COVID-19 and to manage the VTE events associated with elevated AT.

Patients or Materials and methods

We report a retrospective study of 46 patients admitted for COVID-19 infection. Venous duplex ultrasound of lower limbs was performed in all patients at Day 0 and Day 5. All patients had antithrombotic-prophylaxis upon admission using low molecular weight heparin with Enoxaparin. Demographics, comorbidities and laboratory parameters were collected and analyzed.

Results

Elevated AT were reported in 28 patients (61%). 10 had acute VTE events of which eight (17.4%) had aminotransferases disorders. They had been treated with curative Enoxaparin. After a follow-up of 15 and/or 30 days, six of them were controlled, and treated with direct oral anticoagulant (DOACs) after normalization of aminotransferases.

Conclusions

The incidence of aminotransferases disorders associated with acute VTE events in patients infected with COVID-19 is significant. The use of DOACs appear pertinent in these patients. Monitoring of the liver balance should therefore be considered at a distance from the acute episode in the perspective of DOACs relay.

Keywords: COVID-19, Venous thromboembolism, Aminotransferases disorders, Direct oral anticoagulant, Liver disorders, Elevated AST and ALT

1. Introduction

COVID-19 spread in the East of France after a religious meeting in Mulhouse, which gathered about 2000 people from February 17th to 24th 2020. From March 2nd, our hospital had to face a massive inflow of patients presenting acute respiratory failure [1].The largest study on COVID-19 to date showed that the prevalence of elevated aminotransferases (AT) in people faring worst was at least double that of others [2].We further noted that there is a potential link between venous thromboembolic (VTE) events and COVID-19 infection [3]. Before initiating treatment with an oral direct anticoagulant (DOACs), liver function should be assessed. The objective of this work was to evaluate the incidence of aminotransferases disorders in patients hospitalized in a conventional unit infected with COVID-19 and to manage the VTE events associated with elevated AT.

2. Materials and methods

This monocentric retrospective study was approved by the local ethics committee. We had oral consent from our patients for the various practical tests and for all the data provided for this study following the principles outlines in the declaration to Helsinki. From March 2nd to April 11, 46 patients with COVID- 19 infection with mean age (67 ± 12 years) were hospitalized in our unit. 24 (52%) were women. The diagnostics of COVID-19 pneumonia was evaluated by a retrotranscriptase polymerase chain reaction (RT-PCR) of the samples taken with a nasopharyngeal swab. For the patients who were RT-PCR negative, the diagnostics of COVID-19 infection was confirmed by the clinical signs of the infection and the Computed Tomography (CT) following the recommendations of French Society of Thoracic Imaging [3] (Table 1 ).

Table 1.

Lung Parenchyma Lesions on Chest CT : Recommendation of French Society of Thoracic Imaging.

| Chest CT Severity | Extent of Lesions % |

|---|---|

| Stage 1 Minimal | < 10 |

| Stage 2 Moderate | 10−25 |

| Stage 3 Extended | 25−50 |

| Stage 4 Severe | 50−75 |

| Stage 5 Critical | > 75 |

CT without concentration iodine contrast. In patients with COVID-19 we show a characteristic lung parenchyma lesions : ground glass and crazy paving pattern opacity. These lesions are classified in 5 stages.

Complete venous duplex ultrasound (DU) was performed at Day (D) 0 and D 5 by the team of Vascular Medicine. The calf, popliteal, femoral, great and small saphenous veins were explored using the ultrasound machine Samsung HS50.When it was possible we examined iliac veins and inferior vena cava. The main criteria for a positive diagnosis of venous thrombosis were venous incompressibility under the cross-section probe and the direct visualization of the thrombus. The secondary criteria was the absence of the Doppler flow in the vein. DVT was classified as distal (below the popliteal vein) or proximal (popliteal or above popliteal veins. The DU was carried out according to a strict protocol in order to protect the examiner.

Demographics, comorbidities characteristics were collected and laboratory parameters were automatically extracted from our heath information system.

All hospitalized patients had anticoagulation treatment on admission. Classic prophylactic anticoagulation treatment (PAT) is defined by the administration of standard doses of low molecular weight heparin (LMWH) (4000 IU of Enoxaparin every 24 h for patients with a weight less than 100 kg or 6000 IU every 24 h for patients with a weight greater than 100 kg). The patients with a history of VTE had been treated with therapeutic anticoagulation using subcutaneous Enoxaparin (100 UI/12 h).

Qualitative and quantitative variables were analyzed using means or medians, percentages and standard deviations. Univariate analysis were performed, Mann-Whitney and Fisher tests were used to establish the correlation between the variables. P values less than 0.05 were considered to indicate statistical significance.

3. Results

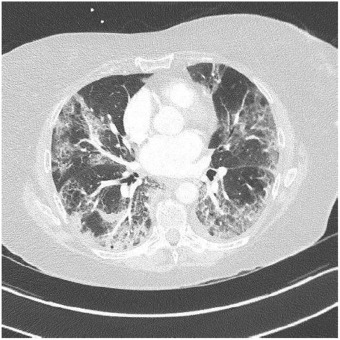

COVID-19 false negative test results can be seen in patients infected [4].PCR was positive in 37 patients (80%), in nine (20%) COVID-19 infection was confirmed with a chest CT showing a characteristical lung parenchyma lesions : bilateral peripheral ground- glass opacities (Fig. 1 ).

Fig. 1.

Lung parenchyma lesions in COVID-19: Patient with COVID-19 infection who presented lung parenchyma lesions on chest CT without iodine contrast, stage (extended lesions 50-75 % of lung parenchyma: bilateral peripheral ground-glass opacities: classification of the French Society of Thoracic Imaging.

Upon admission, we observed elevated C-reactive protein (CRP) (mean 83.3 ± 61.8 mg/l) in 39 patients (84.8%), 29 % had lymphopenia (mean 1.28 ± 1.39 × 10.9/l), 28 % with anemia (mean Hemoglobin 12.7 ± 2.05 g/dl). In our cohort, the activated partial thromblastine time was 1.09 ± 0.298, prothrombin time was 78.3 ± 13.9 %), and glomerular filtration (GF) rate was 78.6 ± 30.mil/min.D-dimer levels and white blood cells rate were significantly associated with VTE events (7317 ± 9550 in the group with VTE versus 1779 ± 2941 ng/ml p = 0.021 and 11.2 ± 4.15 versus 6.83 ± 3.52 × 10.9/L p < 0.01).

Biological cholestasis was observed in 10 patients (21.7%). Patient characteristics are summarized in the Table 2 .

Table 2.

Patient Characteristics.

| variable | Toatal 46 patients | 36 NO VTE | 10 VTE | P value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age (years) | 67.2 ± 12.0 | 67.1 ± 12.1 | 67.6 ± 12.4 | 0.79 |

| F (n,%) M (n,%) |

24 (52%) 22 (48%) |

20 (56%) 16 (44%) |

4 (40%) 6 (60%) |

0.48 |

| AST (<UI/L) | 50.3 ± 34.1 | 50.4 ± 34.7 | 50.1 ± 33.7 | 0.94 |

| ALT (<61UI/L) | 50.3 ± 34.1 | 48.9 ± 31.5 | 91.5 ± 71.0 | 0.16 |

| Total Biluribin (1−17um/L) | 9.90 ± 4.01 | 10.1 ± 4.41 | 9.40 ± 2.84 | 1 |

| D-dimer (<500 ng/mL) | 2914 ± 5362 | 1779 ± 2941 | 7315 ± 9550 | 0.021 |

| GammaGT (15−85 UI/L) | 136 ± 152 | 128 ± 155 | 173 ± 145 | 0.41 |

| Alkaline phosphatase (45−117 UI/L) | 149 ± 206 | 159 ± 230 | 114 ± 70.7 | 0.71 |

| CRP (0−3 mg/L) | 83.3 ± 61.8 | 69.7 ± 53.1 | 110 ± 72.8 | 0.11 |

| GF >90 ml/min) | 78.6 ± 30.0 | 78.1 ± 31.1 | 80.7 ± 26.5 | 1 |

| BMI (kg/m2) | 27.9 ± 4.14 | 27.8 ± 4.03 | 28.3 ± 4.74 | 0.72 |

| aPTT (0.86−1.20) | 1.09 ± 0.298 | 1.09 ± 0.236 | 1.10 ± 0.456 | 0.19 |

| NT-proBNP (<194 pg/mL) | 2388 ± 5361) | 2879 ± 5927 | 483 ± 480 | 0.52 |

| CPK (26−192 UI/L) | 124 ± 83.3) | 134 ± 83.3 | 46.5 ± 19.1 | 0.079 |

| Hemoglobin (13.5−16.9 g/dL) | 12.7 ± 2.05 | 12.5 ± 1.87 | 13.2 ± 2.78 | 0.23 |

| LDH (57−241 UI/L) | 360 ± 151 | 361 ± 159 | 356 ± 134 | 1 |

| Lymphocyes (1.26−3.35 × 10.9/L) | 1.28 ± 1.39 | 1.28 ± 1.57 | 1.27 ± 0.475 | 0.16 |

| Platelets (166−308 × 10.9/L) | 280 ± 108 | 280 ± 108 | 301 ± 87.1 | 0.36 |

| WBC (3.91−10.9 × 10.9/L) | 7.85 ± 4.08) | 6.83 ± 3.52 | 11.2 ± 4.15 | <0.01 |

| Prothrombin time % | 78.3 ± 13.9 | 78.3 ± 15.0) | 78.4 ± 10.7 | 0.91 |

| Home ICU Follow-up care Death |

8 (18%) 4 (11%) 3(6.5%) |

22(63%) 6(17%) 4(11%) 2(8.6%) |

7 (70%) 2(20%) 0 (0%) 1(10%) |

0.87 |

| Hypertension | 25 (54.3%) | 22(5.5%) | 3(30%) | |

| Diabetes | 7 (15.2%) | 7(19.4%) | 0(0%) | |

| Dyslipidemia | 11 (24%) | 10 (27.8%) | 1(10%) | |

| Digestive sypmtoms | 4 (8.7%) | 3 (8.3%) | 1 (10%) | |

| History/liver diseases (n,%) | 0 (0%) | 0(%) | 0(%) | |

| Smoking | 10 (21.7%) | 10 (27.8%) | 0(0%) | |

| Lymphopenia | 29 (63%) | 24(67%) | 5(50%) | |

| Active cancer | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | |

| History of cancer (n,%) | 3 (6.5%) | 3 (8.3%) | 0(0%) | |

| History of VTE (n,%) | 3 (6.5%) | 2(5.5%) | 1(10%) | |

| Chronic Renal Failure | 5 (8.7%) | 5 (13.9%) | 0(0%) | |

| Haemodialysis | 2(4.3%) | 2(5.6%) | 0(0%) | |

| Sleep Apnea Syndrome | 6 (13%) | 4 (11%) | 2(20%) | |

| Septicaemia | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) |

. BMI = Body mass index. CRP = C-reactive protein. LDH = Lactic aciddehydrogenase. ICU = Intensive Care Unit. NT-proBNP = N-terminal prohormone brain natriuretic peptide. aPTT = Activated partial thromblastine time. WBC = White blood cells. CPK = creatine phosphokinase.

Six patients had pulmonary CT angiogram for suspicion of pulmonary embolism (PE) of them three (50%) with acute PE. We reported one primary PE and two associated with proximal deep venous thrombosis of lower limb (DVT).

DU showed acute DVT in nine patients (19.5%) of whom two was diagnosed at D 5 despite PAT. Six were proximal (67%) and three (33%) distal (Table 3 ).In six patients, DVT was without signs and symptoms, two had pain and leg edema (Table 3).

Table 3.

10 patients (21.7%) of the cohort wit VTE.

| P1 | P2 | P3 | P4 | P5 | P6 | P7 | P8 | P9 | P10 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age (years) | 56 | 70 | 72 | 69 | 67 | 79 | 74 | 81 | 79 | 58 |

| Sex | F | M | M | F | F | M | F | M | M | M |

| DVT | DIST | DIST | PROX | PROX | PROX | NON | PROX | PPROX | DIST | PROX |

| PE | NO | NO | Lobar | NO | NO | Lobar | Lobar | CT ND | CT N D | CT ND |

| D-dimer (<500 ng/mL) | 4631 | 1337 | 25,000 | 19,889 | 700 | 4179 | 7261 | N D | N D | 6821 |

| AST (<37 UI/L) | 55 | 115 | 29 | 47 | 30 | 106 | 59 | 47 | 78 | 58 |

| ALT (<61 UI/L) | 23 | 190 | 37 | 171 | 25 | 174 | 72 | 88 | 44 | 102 |

| Total Bilirubin (1−17um/L) | 13 | 7 | 6 | 11 | 9 | 7 | 9 | 8 | 8 | 9 |

| GammaGT(15−85 UI/L) | 384 | 286 | 95 | ----- | 8 | 308 | 21 | N D | 402 | 102 |

| Alkaline Phosphatase 45−117 UI/L | 84 | 126 | 62 | 253 | 61 | 88 | 56 | N D | 319 | 105 |

| aPTT (0.86−1.20) | 0.83 | 1.13 | 1.08 | 0.85 | 1.03 | 1.36 | 1.07 | 1.05 | 1.21 | 1.11 |

| PT % | 75 | 76 | 76 | 62 | 84 | 65 | 82 | 57 | 84 | 87 |

| GF(> 90 mL/min) | 104 | 97 | 92 | 33 | 90 | 55 | 61 | 63 | 65 | 95 |

| Platelets (166−308 × 10.9/L) | 249 | 478 | 249 | 318 | 208 | 311 | 180 | 689 | 251 | 364 |

| Treatment | T.LMWH | T.LMWH | T.LMWH | T.LMWH | T.LMWH | T.LMWH | T.LMWH | T.LMWH | T.LMWH | T.LMWH |

| ICU | NO | Day 2 | NO | Day 1 | NO | NO | NO | NO | NO | NO |

| Death | NO | NO | NO | NO | NO | Day 6 | NO | NO | NO | NO |

| Bleeding | NO | NO | NO | NO | NO | NO | NO | NO | NO | NO |

T.LMWH = Therapeutic lower molecular weight heparin. Total Bil = Total Bilirubin. DIST = distal. PROX = Proximal CT = Computed tomography. ND =not done. PT = Prothrombin time. P = Patient.

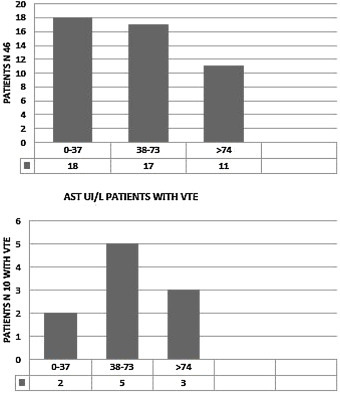

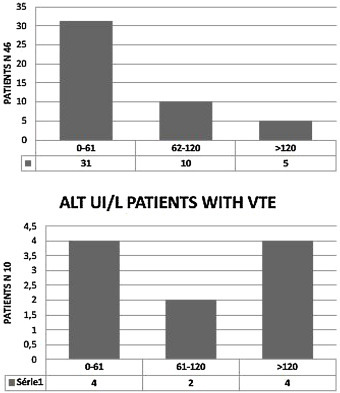

We observed elevated AT in 28 patients (68.3%),11 of them (24%) had hepatic impairment with AST twice normal (normal <37 UI/). In five (11%) ALT was twice normal (normal < 61 UI/L). Of the 10 patients with VTE, eight (80%) had elevated AT. AST > 74 UI/L was reported in three patients (37.5%) (Fig. 2 ) and four (50%) had ALT > 120 UI/L. (Fig. 3 ). Total Bilirubin rate was normal in all patients (mean 9.90 ± 4.01 um/l).

Fig. 2.

AST disorders in the cohort (46 patients) and in the patients with VTE (10 patients) AST UI/L, normal < 37 UI/L.

Fig. 3.

ALT disorders in the cohort (46 patients) and in the patients with VTE (10 patients) ALT UI/L, normal< 61 UI/L.

Four patients (8.7%) described digestive symptomatology (abdominal pain and nausea). None of our patients had history of liver diseases, two had history of VTE. The management consisted of a bi-antibiotic therapy with Cefotaxime and Azithromycin /IV, paracetamol and oxygen therapy. The patients without acute VTE received PAT, those with acute VTE had a therapeutic anticoagulation with Enoxaparin (100 UI/12 h); however, no bleeding tendency was noted (no bruise, hematoma, digestive bleeding or epistaxis were detected). During hospitalization the evolution was marked by a stability of liver enzymes without aggravation after the initiation of the different therapies.

Eight patients (17.4%) were transferred to the Intensive Care Unit (ICU) for acute respiratory failure. Elevated platelets rate was significantly associated with the transfer (mean326 ± 69.0 versus 270 ± 113 × 10.9/L, p = 0.046) (Table 4 ).

Table 4.

8 patients(17.4%) Patients Transferred to ICU.

| Variable | NO ICU n = 38 | ICU n = 8 | P value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age (years) | 68.4 ± 12.3 | 61.5 ± 9.12 | 0.15 |

| ALT (<61 UI/L) | 56.7 ± 44.7 | 65.2 ± 53.2 | 0.67 |

| AST (<37UI/L) | 52.3 ± 35.6) | 52.2 ± 32.5 | 0.73 |

| Total Biluribin (1−17um/L) | 9.79 ± 3.97 | 9.79 ± 3.97 | 0.77 |

| GammaGT (15−85 UI/L) | 116 ± 131) | 276 ± 227 | 0.06 |

| Alkaline phosphatase (45−117 UI/L) | 192 ± 132 | 0.12 | |

| D-dimer (<500 ng/mL) | 2885 ± 5066 | 3522 ± 6647 | 0.91 |

| VTE (n,%) | 8(21%) | 2(25%) | 1 |

| GF (>90 ml/min) | 78.0 ± 27.9 | 81.8 ± 40.7 | 0.14 |

| BMI (kg/m2) | 27.5 (±4.34) | 29.6 (±2.76) | 0.13 |

| CPK (26−192 UI/L) | 143 (±91.1) | 76.6 (±25.7) | 0.17 |

| LDH (57−241 UI/L) | 374 (±136) | 325 (±194) | 0.41 |

| Hemoglobulin (13.5−16.9 g/dL) | 12.9 (±1.96) | 11.7 (±2.38 | 0.086 |

| Lymphocytes (1.26−3.35 × 10.9/L) | 1.31 (±1.53) | 1.15 (±0.522) | 0.68 |

| NT-proBNP (<194 pg/mL) | 2731 (±5945) | 1056 (±1400) | 0.97 |

| Platelets (166−308 × 10.9/L) | 270 (±113) | 326 (±69.0) | 0.046 |

| Bleeding (n,%) | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) |

Three patients died (6.5%). The age (mean 83.3 ± 6.66 versus 65.5 ± 10.9 years, p value 0.017), AST (mean 125 ± 21.9 versus 84.2 ± 69.4 UI/L p < 0.01), GF rate (mean 35.2 ± 17.8 versus 82.9 ± 27.6 mL/min p < 0.01), white blood cells (mean 12.3 ± 3.13 versus7.52 ± 3.97 × 10.9/l, p = 0.048) and N-terminal prohormone brain natriuretic peptide rate (mean 8665 ± 7169 versus 1865 (±4960) pg/mL, p = 0.025) were significantly associated with death. The threepatients indeed died in the conventional unit after cardio-respiratory failure (Table 5 ).

Table 5.

3 patients (6.5%) Patients died.

| SURVIVED n = 43 (91.3%) | DIED n = 3 (8.7%) | P value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age | 65.5 ± 10.9 | 83.3 ± 6.66 | 0.017 |

| ALT (<61 UI/L) | 55.7 ± 43.3 | 106 ± 65.6) | 0.097 |

| AST (< 37 IU/L) | 84.2 ± 69.4 | 125 ± 21.9 | <0.01 |

| Total Biluribin (17um/L) | 9.89 ± 4.16 | 8.50 ± 2.12 | 0.85 |

| GammaGT (15−85 UI/L) | 140 ± 155 | 128 ± 158 | 0.87 |

| Alkaline phosphatase (45−117 UI/L) | 156 ± 218 | 107 ± 29.8 | 0.33 |

| d-dimer (<500 ng/mL) | 3118 ± 5596 | 2060 ± 1594 | 0.72 |

| VTE (n,%) | 9(21.4%) | 1(33%) | 0.54 |

| GF (>90 ml/min) | 82.9 ± 27.6 | 35.2 ± 17.8 | <0.01 |

| BMI (kg/m2) | 28.1 ± 4.11 | 27.9 ± 4.14 | 0.71 |

| WBC (3.91−10.9 × 10.9/L | 7.52 ± 3.97 | 12.3 ± 3.13 | 0.048 |

| Lymphocytes (1.26−3.35 × 10.9/L) | 1.05 ± 0.514 | 4.32 ± 4.54 | 0.082 |

| Platelets (166−308 × 10.9/L) | 281 ± 111 | 272 ± 76.7 | 0.96 |

| NT-proBNP (<194 pg/mL) | 1865 (±4960) | 8665 ± 7169 | 0.025 |

| LDH (57-241 UI/L) | 366 ± 157 | 304 ± 79.9 | 0.59 |

| Hemoglobulin (13.5-16.9 g/dL) | 12.8 ± 1.97 | 10.8 ± 3.03 | 0.3 |

| Prothombin Time (%) | 78.0 ± 13.9 | 82.7 ± 15.3 | 0.5 |

| CPK (26-192 UI/L) | 124 ± 83.3 | 96.5 ± 47.4 | 0.75 |

| Bleeding (n,%) | 0 (0%) | 0 (%) | |

| DeadP1 | DeadP2 | DeadP3 | |

| Age (years) | 79 | 80 | 92 |

| GF (>90 ml/min) | 55 | 12 | 34 |

| WBC (3.91−10.9 × 10.9/L) | 10.56 | 15.92 | 10.43 |

| AST (< 37 UI/L) | 115 | 120 | 149 |

| NT-proBNP (<194 pg/mL) | 1319 | 15,643 | 9032 |

| VTE | Lobar PE | NO | NO |

After their discharge, the patients with VTE were treated at home with therapeutic Enoxaparin (100 UI/12 h), and those without VTE with PAT for 14 days.

With follow-up of 15 and 30 days, we controlled six patients (75%) who had VTE with elevated AT. A treatment with curative DOACs was initiated after normalization of the aminotransferases at Day 15 in fourpatients, in two DAOCs was started at Day 30 (Table 6 ).

Table 6.

Follow-up Patients D15- D 30.

| Variable | P 1 | P 7 | P 9 | P 8 | P2 | P10 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age (years) | 56 | 74 | 79 | 81 | 70 | 58 |

| Sex | F | F | M | M | M | M |

| AST D0 UI/L | 55 | 74 | 78 | 80 | 70 | 58 |

| ALT D 0 UI/L | 22 | 59 | 44 | 47 | 115 | 102 |

| DVT | D5 distal | D0 Proximal | D0 Distal | D0 Proximal | D0 Distal | D0 Proximal |

| PE | NO | LOBAR | PCTA ND | PCTA ND | NO | PCTA ND |

| Transfer ICU | NO | NO | NO | NO | D2 after admission | NO |

| Death | NO | NO | NO | NO | NO | NO |

| AST D15 | 18 | 30 | 19 | 39 | 50 | 52 |

| ALT D15 | 6 | 45 | 17 | 51 | 100 | 85 |

| AST D30 | ------- | ------ | ------- | ---- | 22 | 22 |

| ALT D30 | ------- | ------- | -------- | ------ | 60 | 66 |

| Bleeding | NO | NO | NO | NO | NO | NO |

| DOACs | D15 | D15 | D15 | D15 | D30 | D30 |

PCTA ND = Pulmonary CT angiogram not done.

At D30 after their discharge, 12 patients who had elevated AT without VTE were checked. In 10 patients, liver enzymes were normal.

4. Discussion

Thrombosis associated with acute viral infection has been described in the literature. The incidence of thrombosis among hospitalized patients with acute cytomegalovirus (CMV) infection has been studied once by Atzmony L et al. [5]; they retrospectively studied the incidence of DVT as among 140 consecutive patients with acute CMV infection, the incidence of DVT was 2.9%.. In our cohort infected with COVID-19, the prevalence of DVT at Day 0 was 9.7%. A relationship between VTE has been reported in patients with COVID-19 pneumonia.

Cui S. et al. [3] described 25 % of DVT in 81 patients hospitalized in ICU with COVID-19 pneumonia with elevated D-dimer levels. Middeldrop S. et al. [6] reported 20% of VTE events in 198 patients with COVID-19 pneumonia (38% in ICU) during follow-up of 7 days. 21.7 % of our patients had acute VTE with follow-up of 5 days (1 primary PE and 9 DVT).

The significant increase of D-dimer in severe COVID-19 patients is a good index for identifying high-risk groups of VTE. The patients need PTA and in some cases curative anticoagulant treatment [3]. In our study, D-dimer levels were significantly associated with VTE and all the patients had PTA upon admission.

Many viral infections provoke aminotransferases disorders, viral hepatitis in the first place [7]. Other viruses can also disrupt liver function such as CMV [8]. Elevated AT was also observed in respiratory tropism viruses such as Middle East Respiratory Syndrome-Cov [9] and severe acute respiratory syndrome-Cov (SARS) [10].The pathophysiology of the new SARS-Cov-2 virus is still poorly understood but it is admitted that there are forms with digestive symptomatology [11]. In our population,four patients (8.7%) of 46 had digestive signs and symptoms.

Review of the Chinese studies covering 8 studies for a total of 1,628 patients, showed rates ranging from 16.1% to 53.1% of elevated TA during infection with SARS-Cov-2 [12]. Aminotransferases disorders were observed in our cohort in 28 patients (61 %) of them 24% had AST twice normal and in 11% the ALT.

DOACs are indicated in the treatment of thromboembolic events. However, some precautions should be taken before considering their use, especially in cirrhotic patients, cancer, «extreme» weights (≤60 and > 100 kg) [13].Rarely DOACs can indeed cause liver disorders even in patients without particular risk [14]. The patients with significant hepatic impairment (aminotransferases and bilirubin double) normal) were excluded from studies with DOACs. In the presence of significant hepatic impairment and according to the Child-Pugh classification, DOACs may be used with caution [15].We were facing a new pathology, the oral treatment with warfarin was also likely to be compromised [16]. For this reason, we preferred to treat all patients with VTE who had elevated AT with therapeutic LMWH until the standardization of the biological balance sheet.

Patients infected with COVID-19 have an excessive inflammation with a cytokine storm [17], elevated CRP in our population (84.8%) could be related to the inflammatory response.

Our study is limited due to the very small number of patients; the significance of elevated AT and VTE events associated with these disorders may have been influenced by this limited cohort. COVID-19 infection is frequently complicated by elevated AT and VTE. The use of DOACs in the acute VTE in these patients does not appear pertinent. Monitoring of the liver balance should therefore be considered at a distance from the acute episode in the perspective of DOACs relay.

The patients with COVID-19 pneumonia have a profound hypercoagulable state, and complicating venous thrombotic events are common. COVID-19 infection fulfil the three criteria of the Virchow triad among hypercoagulability, endothelial dysfunction [18] and stasis. Hospitalized COVID-19 patients require an early administration of PTA with LMWH as part of their treatment. Based on these findings, these patients also require a follow-up with vein ultrasonography. DU is a quick, easy and non invasive exam.AbbreviationsVTEVenous thromboembolismATAminotransferasesASTAspartate aminotransferaseDOACsDirect oral anticoagulant CPKCreatine Phosphokinase DVTDeep venous thrombosisPEPulmonary EmbolismLMWHLower molecular weight heparinPATProphylactic anticoagulation treatmentDUDuplex ultrasoundGFGlomerular filtrationCRPC-reactive proteinRT-PCRTranscriptase polymerase chain reactionALTAlanine aminotransferaseCTComputed tomographyICUIntensive care unitCMVCytomegalovirusSARSSevere acute respiratory syndromeDDay

Abbreviations

- VTE

Venous thromboembolism

- AT

Aminotransferases

- AST

Aspartate aminotransferase

- DOACs

Direct oral anticoagulant

- CPK

Creatine Phosphokinase

- DVT

Deep venous thrombosis

- PE

Pulmonary Embolism

- LMWH

Lower molecular weight heparin

- PAT

Prophylactic anticoagulation treatment

- DU

Duplex ultrasound

- GF

Glomerular filtration

- CRP

C-reactive protein

- RT-PCR

Transcriptase polymerase chain reaction

- ALT

Alanine aminotransferase

- CT

Computed tomography

- ICU

Intensive care unit

- CMV

Cytomegalovirus

- SARS

Severe acute respiratory syndrome

- D

Day

Sources of funding

None.

Conflicts of interest

The authors declare that there is no conflict of interest for this publication.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank Mrs. Floralie GALLION and Mrs. Céline LAPIERRE to their precious help in the data collection

References

- 1.Kuteifan K., Pasquier P., Meyer C., Escarment J., Theissen O. The Outbreak of COVID-19 in Mulhouse : Hospital Crisis Management and Deployment of Military Hospital During the Outbreak of COVID-19 in Mulhouse. France. Ann Intensive Care. 2020;10(1):59. doi: 10.1186/s13613-020-00677-5. doi.org/10.1186/s13613-020-00677. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Zhang C., Shi L., Sheng Wang F. Liver injury in COVID-19: management and challenges. Lancet Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2020;5(5):428–430. doi: 10.1016/S2468-1253(20)30057-1. doi.org/10.16/S2468-1253(20)30057-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Cui S., Chen S., Li X., Liu S., Wang F. Prevalence of venous thromboembolism in patients with severe novel coronavirus pneumonia. J Thromb Haemost JTH. 2020 doi: 10.1111/jth.14830. doi :10.111/jth.14830. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.La société d’Imagerie Thoracique propose un compte-rendu structuré de scanner thoracique pour les patients suspects de COVID-19 [Internet]. SFR e-Bulletin. 2020 [cited 2020 Apr 29]. Available from: https://ebulletin.radiologie.fr/actualites-covid-19/societe-dimagerie-thoracique-propose-compte-rendu-structure-scanner-thoracique.Article in French.

- 5.Lauren M., Kucirka L.M., Lauer S.A., Laeyendecker O., Boon D., Lessler J. Variation in false negative rate of reverse transcriptase polymerase chain reaction–Based SARS- CoV-2 tests by time since exposure. Ann Intern Med. 2020 doi: 10.7326/M20-1495. M20-1495. doi: 10.7326/M 20-1495. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Atzmony L., Halutz O., Avidor B., Finn T., Zimmerman O., Steinvil A. Incidence of cytomegalovirus-associated thrombosis and its risk factors: a case-control study. Thromb Res. 2010;126(6):e439–443. doi: 10.1016/j.thromres.2010.09.006. doi.org/10.1016/j.thromres.2010.09006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Middeldorp S., Coppens M., Van Haaps T.F., Foppen M., Vlaar A.P. Incidence of venous thromboembolism in hospitalized patients with COVID-19. Journal Throm Haemost. and Haemostasis. 2020;18(8):1995–2002. doi: 10.1111/jth.14888. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Blasco-Perrin H., Péron J.-M. Hepatic and extra-hepatic manifestations of hepatitis E virus infection. Presse Med. 2018;47(7-8 Pt 1):620–624. doi: 10.1016/j.lpm.2015.04.017. doi:10.1016/j.lpm.2015.04.017. Article in French. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Jensen K.O., Angst E., Hetzer F.H., Gingert C. Acute cytomegalovirus hepatitis in an immunocompetent host as a reason for upper right abdominal pain. Case Rep Gastroenterol. 2016;10(1):36–43. doi: 10.1159/000442972. doi:10.1159/000442972. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Azhar E.I., Hui D.S.C., Memish Z.A., Drosten C., Zumla A. The middle east respiratory syndrome (MERS) Infect Dis Clin North Am. 2019;33(4):891. doi: 10.1016/j.idc.2019.08.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Chau T.-N., Lee K.-C., Yao H., Tsang T.-Y., Chow T.-C., Yeung Y.-C. SARS-associated viral hepatitis caused by a novel coronavirus: report of three cases. Hepatology. 2004;39(2):302–310. doi: 10.1002/hep.20111. doi:10.1002/hep.20111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Gu J., Han B., Wang J. COVID-19: gastrointestinal manifestations and potential fecal–oral transmission. Gastroenterology. 2020;158(6):1518–1519. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2020.02.054. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Tran H., Joseph J., Young L., McRae S., Curnow J., Nandurkar H. New oral anticoagulants: a practical guide on prescription, laboratory testing and peri-procedural/bleeding management. Australasian Society of Thrombosis and Haemostasis. Intern Med J. 2014;44(6):525–536. doi: 10.1111/imj.12448. doi:10.5694/mja2.50004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Cordeanu M., Gaertner S., Bensalah N., Hamade A. Stephan D. Rivaroxaban induced liver injury: a cholestatic pattern. Int J Cardiol. 2016;216:97–98. doi: 10.1016/j.ijcard.2016.04.063. 8.doi:10.1016/j.icard.2016.04.063. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Bornet S., Dolapsakis C., Petignat P.A. Gobin N. Direct oral anticoagulants : some practical consideraions. Rev Med Suisse. 2016;12(529):1453–1459. Article in French. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kow C.S., Sunter W., Bain A., Zaidi S.T., Hasan S.S. Management of outpatient warfarin therapy amid COVID-19 pandemic: a practical guide. Am J Cardiovasc Drugs. 2020:1–9. doi: 10.1007/s40256-020-00415-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Jose R.J., Manuel A. COVID-19 cytokine storm: the interplay between inflammation and coagulation. Lancet Respir Med. 2020;8(6):e46–e47. doi: 10.1016/S2213-2600(20)30216-2. doi.org/10.1016/S2213-2600(20)30216-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Varga Z., Flammer A.J., Steiger P., Haberecker M., Andermatt R., Annelies S. Endothelial cell infection and endotheliitis in COVID-19. Lancet. 2020;395(10234):1417–1418. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(20)30937-5. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(20)30937-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]