Abstract

Background

Patients with coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) commonly present with fever, constitutional symptoms, and respiratory symptoms. However, atypical presentations are also well known. Though isolated mesenteric arterial occlusion associated with COVID-19 has been reported in literature, combined superior mesenteric arterial and venous thrombosis is rare. We report a case of combined superior mesenteric arterial and venous occlusion associated with COVID-19 infection.

Case Report

We report a case of a 45-year-old man who was a health care worker who presented to the emergency department with severe abdominal pain. The clinical examination was unremarkable, but imaging revealed acute mesenteric ischemia caused by superior mesenteric artery and superior mesenteric vein occlusion. Imaging of the chest was suggestive of COVID-19 infection, which was later confirmed with reverse transcription polymerase chain reaction of his nasopharyngeal swab. To date, only 1 case of combined superior mesenteric artery and superior mesenteric vein thrombosis caused by COVID-19 has been reported.

Why Should an Emergency Physician Be Aware of This?

During the COVID-19 pandemic it is important to keep mesenteric ischemia in the differential diagnosis of unexplained abdominal pain. Routinely adding high-resolution computed tomography of the chest to abdominal imaging should be considered in patients with acute abdomen because it can help to identify COVID-19 immediately. © 2020 Elsevier Inc.

Keywords: COVID-19, emergency department, superior mesenteric artery occlusion, superior mesenteric vein occlusion

Introduction

Coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) caused by the novel severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 has caused a devastating pandemic affecting >81 million people resulting in 1.8 million deaths worldwide as of January 1, 2021 (1). More than a year into the epidemic, our knowledge of the virus and the disease is quite limited. Patients with COVID-19 common present with fever, constitutional symptoms, and respiratory symptoms. However, atypical presentations are well known, particularly arterial or venous occlusion including stroke, myocardial infarction, acute limb ischemia, mesenteric ischemia, deep venous thrombosis, and pulmonary embolism (2). We report an unusual combination of superior mesenteric artery (SMA) and superior mesenteric vein (SMV) occlusion in a patient with COVID-19.

Case Report

A 45-year-old man working as a health care worker in our hospital presented to the emergency department (ED) with acute abdominal pain of 2 hours’ duration. The pain was excruciating in nature and did not respond to narcotic analgesia. The pain was felt in the epigastric and umbilical region and did not radiate anywhere else. He vomited once and the vomitus was unremarkable. There was no fever, loose stools, hematemesis, melena, or bleeding per rectum. He did not have any comorbidities and was not taking any medications regularly. On examination he was diaphoretic, but his vital signs were stable with a pulse rate of 58 beats/min, blood pressure of 140/90 mm Hg, a respiratory rate of 18 breaths/min, and oxygen saturation of 98% on room air. His abdomen was soft, nontender, and nondistended, with normal bowel sounds. Cardiovascular and respiratory systems were unremarkable. An electrocardiogram revealed sinus bradycardia but was otherwise normal. Initially, he was treated with intravenous pantoprazole, ondansetron, and morphine. The pain did not resolve and he was also given fentanyl for pain relief.

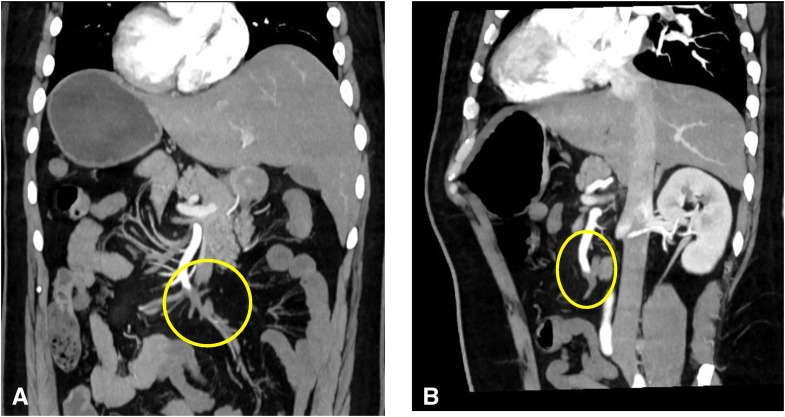

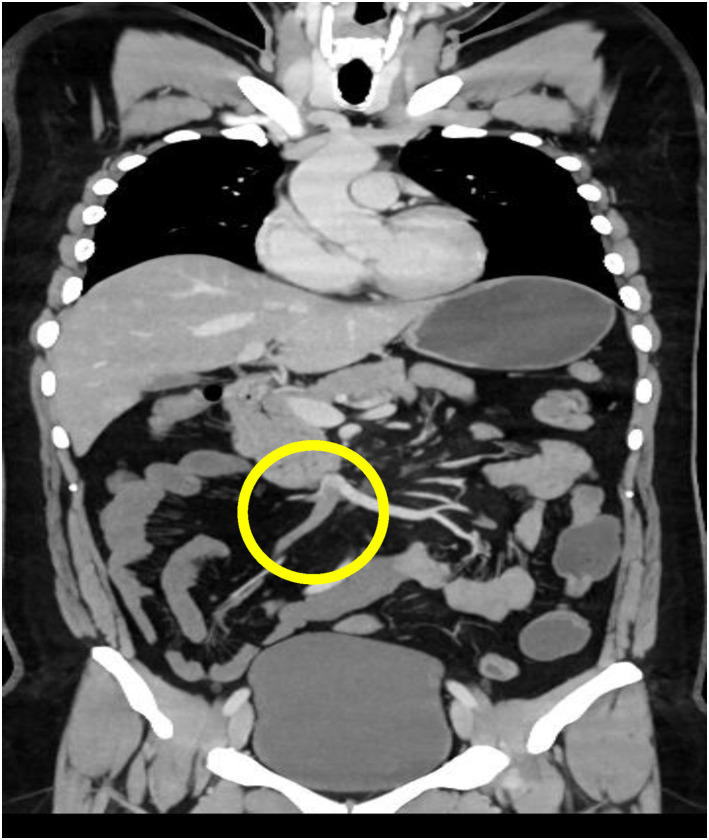

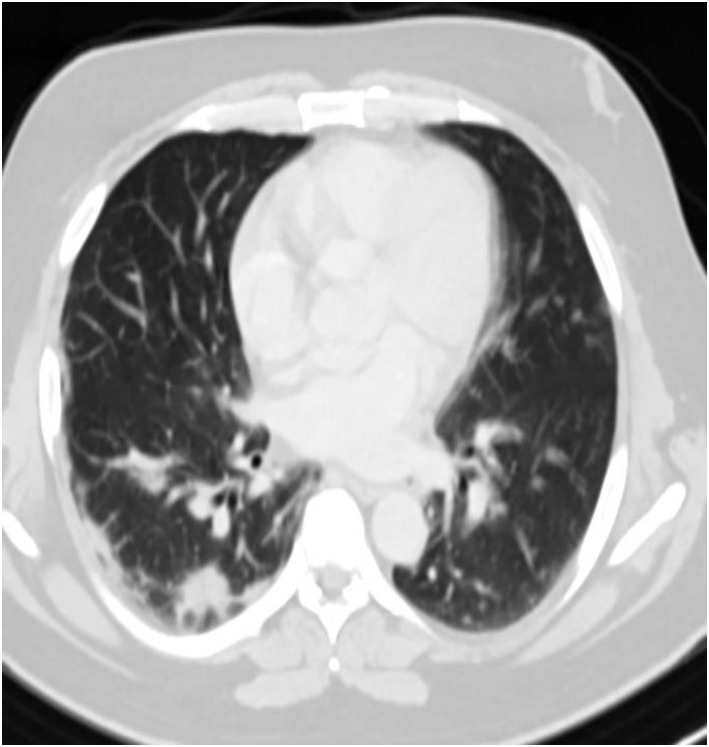

Radiographs and ultrasound of the abdomen were normal. Given his persistent pain, which was out of proportion to the examination findings, mesenteric ischemia was suspected, and the patient underwent an emergency computed tomography (CT) angiogram. CT angiography revealed a thrombotic occlusion of the SMA and SMV (Figure 1, Figure 2 ). To our surprise, the abdominal imaging, which covered the lower part of the lungs, revealed features suggestive of COVID-19 infection. The patient had a high-resolution CT scan of his thorax, which revealed bilateral peripheral ground glass opacities with a CO-RADS grade of 5 and a CT severity index of 5 (Figure 3 ). The patient had not reported any COVID-19–related symptoms at presentation, but on careful questioning we also obtained information that he had a mild fever and sore throat for 5 days before presentation and for which he did not seek medical attention. A reverse transcriptase polymerase chain reaction study of his nasopharyngeal swab came back positive for severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2. His transthoracic echocardiogram showed a normal left ventricular ejection fraction with no evidence of clot. His blood investigations revealed a lipase of 40 IU/L, lactate dehydrogenase of 1.3 mmol/L, D-dimer of 5.30 mg/L (reference <0.50 mg/L), a serum ferritin level of 324.3 ng/ml, and a normal CRP. Once the diagnosis was confirmed the patient was started on an intravenous course of unfractionated heparin. He was immediately taken for laparotomy with SMA thrombectomy. A relook laparotomy after 48 h revealed a 103-cm long gangrenous bowel segment that was resected and end jejunostomy with distal ileal mucous fistula was performed.

Figure 1.

Coronal reconstruction (A) and sagittal oblique reconstruction (B) of the arterial abdominal computed tomography scan showing superior mesenteric artery thrombus.

Figure 2.

Coronal reconstruction of the portal abdominal computed tomography scan showing a superior mesenteric vein thrombus.

Figure 3.

High-resolution computed tomography scan of the basal lung segments showing peripheral ground glass opacities.

Discussion

COVID-19 creates a prothrombotic milieu. It predisposes the patient to both micro- and macrovascular thrombosis, which predominantly affects the venous system (3). Arterial occlusion is less common, mostly affecting the cerebral and coronary vessels (Table 1 ). There are only a few case reports of COVID-19–related SMA thrombosis. The exact mechanism for thrombosis in COVID-19 is unknown. Hypoxia, inflammatory mediators, thrombocythemia, immobilization, and liver injury secondary to angiotensin-converting enzyme 2 receptor expression are the proposed mechanisms (3). In general, pre-existing cardiac disease, peripheral artery disease, advanced age, traumatic injury, and low cardiac output states are the major risk factors for acute mesenteric arterial occlusion (4). Our patient did not have any such risk factors making us suspect COVID-19–related thrombosis.

Table 1.

Incidence of Thromboembolism in Patients with COVID-19 Based on the Studies Published on Hypercoagulability in COVID-19

| Type of Thromboembolism | Abou-Ismail et al. (7) Incidence, % (Min–Max) | Singhania et al. (12) Incidence, % (Min–Max) |

|---|---|---|

| VTE | 18.7–69 | 4.4–79 |

| ACS | 1.1 | 1.1 |

| Ischemic stroke | 1.3–3.7 | 1.3–3.7 |

| Mesenteric ischemia | 0.7 | 0.7 |

| Acute limb ischemia | 0.7–16.3 | 0.7–16.3 |

ACS = acute coronary syndrome; COVID-19 = coronavirus disease 2019; VTE = venous thromboembolism.

Seven cases of COVID-19–related SMA thrombosis have been reported so far, and in that small sample just 1 patient had both SMA and SMV thrombosis (5). Of those 7 patients, 5 presented with respiratory symptoms and subsequently developed SMA thrombosis during their hospital stay, but 2 of them had abdominal pain as their only presenting symptom (Table 2 ).

Table 2.

Demographic and Clinical Characteristics of the Reported Cases of Mesenteric Ischemia in COVID-19

| Author, Month, and Year | Age, Years | Gender | Comorbidities | Complaint for Which Patient Was Admitted | D-Dimer/CRP Levels on Day of Admission | Treatment Given | Outcome |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| de Barry et al. (5), April 2020 | 79 | F | None | Abdominal pain | NA/125 mg/dL | Thrombectomy and intestinal resection | Died |

| A Beccara et al. (13), April 2020 | 52 | M | None | Respiratory symptoms | NA/44 mg/dL | Intestinal resection with side-to-side anastomosis | Survived |

| Ignat et al. (14), May 2020 | 28 | F | None | Abdominal pain | NA/NA | Bowel resection and laparostomy | Survived |

| Ignat et al. (14), May 2020 | 56 | M | Diabetes and hypertension | Respiratory symptoms | NA/NA | Bowel resection and laparostomy | Not known |

| Ignat et al. (14), May 2020 | 67 | M | Chronic bronchitis, diabetes, status postcardiac transplant | Respiratory symptoms | NA/NA | Medical treatment | Died |

| Bianco et al. (15), June 2020 | 59 | M | Hypertension | Respiratory symptoms | 30-fold increase/NA | Small bowel resection with side-to-side anastomosis | Died |

| Karna et al. (16), July 2020 | 61 | F | Diabetes and hypertension | Respiratory symptoms | NA/343 mg/dL | Resection of gangrenous bowel and loop ileostomy | Died |

COVID-19 = coronavirus disease 2019; CRP = C-reactive protein; F = female; M = male; NA = not available.

Studies have shown that D-dimer tends to rise early in mesenteric ischemia and has a sensitivity of 95% in diagnosing intestinal ischemia. Consistently elevated D-dimer is also an independent predictor of poor outcomes (6,7). Our patient had an elevated D-dimer and normal CRP values at presentation. During his hospital stay, D-dimer remained elevated but CRP continued to be normal. This phenomenon may represent the resolution of COVID-19 infection but an ongoing thromboembolism. A similar discrepancy in the values of D-dimer and CRP over time—such as an elevated D-dimer and declining CRP levels—was observed in a case series of pulmonary embolism caused by COVID-19 (8). In COVID-19, a high CRP level is associated with an increase in disease severity (9). Our patient had normal CRP levels, presumably because he had only mild disease (no constitutional or respiratory symptoms at presentation and a CT severity score of only 5, suggesting mild disease).

Ultrasound examination in the early phase may show SMA occlusion and bowel spasm. In the intermediate phase, ultrasound is not useful because of the presence of an increased amount of gas-filled intestinal loops. In the late phase, ultrasound may reveal fluid-filled lumen, bowel wall thinning, evidence of extraluminal fluid and decreased or absent peristalsis (10). CT angiography is the best diagnostic modality and has a sensitivity and specificity of 89.4% and 99.5%, respectively, for diagnosing acute mesenteric ischemia (11).

In thrombotic mesenteric arterial occlusion, fluid resuscitation, analgesia, anticoagulation, and broad-spectrum antibiotics should be started in the ED, after which the patient should be taken for emergency laparotomy (4).

Why Should an Emergency Physician Be Aware of This?

We have described a case of combined SMA and SMV thrombosis related to COVID-19 infection. This is the second such case report in the world and first from Asia. Sudden onset persistent abdominal pain that remains unexplained by clinical evaluation and basic investigations should raise the suspicion of mesenteric ischemia, and a COVID-19–related prothrombotic state should be considered. D-dimer is a highly sensitive investigation for the prothrombotic state caused by COVID-19. Further evaluation of COVID-19, including reverse transcriptase polymerase chain reaction and a high-resolution computed tomography scan of the chest are essential. Examining the lower parts of the lung visible in the abdominal imaging itself can detect COVID-19.

Acknowledgments

Informed consent was obtained from the patient for the publication of the case report and the use of perioperative data for research purposes.

Footnotes

Reprints are not available from the authors.

References

- 1.World Health Organization website WHO coronavirus disease (COVID-19) dashboard. https://covid19.who.int Available at:

- 2.Pan L., Mu M., Yang P., et al. Clinical characteristics of COVID-19 patients with digestive symptoms in Hubei, China: a descriptive, cross-sectional, multicenter study. Am J Gastroenterol. 2020;115:766–773. doi: 10.14309/ajg.0000000000000620. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Klok F.A., Kruip M.J.H.A., van der Meer N.J.M., et al. Incidence of thrombotic complications in critically ill ICU patients with COVID-19. Thromb Res. 2020;191:145–147. doi: 10.1016/j.thromres.2020.04.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Oldenburg W.A., Lau L.L., Rodenberg T.J., Edmonds H.J., Burger C.D. Acute mesenteric ischemia: a clinical review. Arch Intern Med. 2004;164:1054–1062. doi: 10.1001/archinte.164.10.1054. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.de Barry O., Mekki A., Diffre C., Seror M., El Hajjam M., Carlier R.Y. Arterial and venous abdominal thrombosis in a 79-year-old woman with COVID-19 pneumonia. Radiol Case Rep. 2020;15:1054–1057. doi: 10.1016/j.radcr.2020.04.055. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Montagnana M., Danese E., Lippi G. Biochemical markers of acute intestinal ischemia: possibilities and limitations. Ann Transl Med. 2018;6:341. doi: 10.21037/atm.2018.07.22. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Abou-Ismail M.Y., Diamond A., Kapoor S., Arafah Y., Nayak L. The hypercoagulable state in COVID-19: incidence, pathophysiology, and management. Thromb Res. 2020;194:101–115. doi: 10.1016/j.thromres.2020.06.029. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Becher Y., Goldman L., Schacham N., Gringauz I., Justo D. D-dimer and C-reactive protein blood levels over time used to predict pulmonary embolism in two COVID-19 patients. Eur J Case Rep Intern Med. 2020;7:001725. doi: 10.12890/2020_001725. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Gong J., Dong H., Xia Q.S., et al. Correlation analysis between disease severity and inflammation-related parameters in patients with COVID-19: a retrospective study. BMC Infect Dis. 2020;20:963. doi: 10.1186/s12879-020-05681-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Reginelli A., Genovese E., Cappabianca S., et al. Intestinal ischemia: US-CT findings correlations. Crit Ultrasound J. 2013;5(suppl 1):S7. doi: 10.1186/2036-7902-5-S1-S7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Henes F.O., Pickhardt P.J., Herzyk A., et al. CT angiography in the setting of suspected acute mesenteric ischemia: prevalence of ischemic and alternative diagnoses. Abdom Radiol N Y. 2017;42:1152–1161. doi: 10.1007/s00261-016-0988-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Singhania N., Bansal S., Nimmatoori D.P., Ejaz A.A., McCullough P.A., Singhania G. Current overview on hypercoagulability in COVID-19. Am J Cardiovasc Drugs. 2020;20:393–403. doi: 10.1007/s40256-020-00431-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Beccara L., Pacioni C., Ponton S., Francavilla S., Cuzzoli A. Arterial mesenteric thrombosis as a complication of SARS-CoV-2 infection. Eur J Case Rep Intern Med. 2020;7:001690. doi: 10.12890/2020_001690. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ignat M., Philouze G., Aussenac-Belle L., et al. Small bowel ischemia and SARS-CoV-2 infection: an underdiagnosed distinct clinical entity. Surgery. 2020;168:14–16. doi: 10.1016/j.surg.2020.04.035. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Bianco F., Ranieri A.J., Paterniti G., Pata F., Gallo G. Acute intestinal ischemia in a patient with COVID-19. Tech Coloproctol. 2020;24:1217–1218. doi: 10.1007/s10151-020-02255-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Karna S.T., Panda R., Maurya A.P., Kumari S. Superior mesenteric artery thrombosis in COVID-19 pneumonia: an underestimated diagnosis - first case report in Asia. Indian J Surg. 2020 doi: 10.1007/s12262-020-02638-5. [Epub ahead of print] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]