Abstract

At present, the time-frame used for the quarantine of individuals with coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) is the entire duration of symptoms plus 14 days after symptom recovery; however, no data have been reported specifically for healthcare workers (HCWs). In the study population of 142 HCWs with COVID-19, the mean time for viral clearance was 31.8 days. Asymptomatic subjects cleared the virus more quickly than symptomatic subjects (22 vs 34.2 days; P<0.0001). The presence of fever at the time of diagnosis was associated with a longer time to viral clearance (relative risk 11.45, 95% confidence interval 8.66–14.25; P<0.0001). These findings may have a significant impact on healthcare strategies for the future management of the COVID-19 pandemic.

Introduction

Severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus-2 (SARS-CoV-2), a novel RNA coronavirus from the same family as severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus (SARS-CoV) and Middle East respiratory syndrome coronavirus, was identified in early January 2020 as the cause of a pneumonia epidemic affecting the city of Wuhan, from where it spread rapidly across China [1,2]. From China, infection rapidly reached Europe, the USA and South America, with the number of new cases increasing every day [3,4]. The World Health Organization (WHO) declared coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) as a pandemic due to widespread infectivity and high contagion rate [5].

Initial healthcare strategies to reduce the risk of spreading included symptom-based case detection and subsequent testing to guide isolation and quarantine. This approach was borrowed from that used for SARS-CoV due to the similarities between the infections. Despite these similarities, SARS-CoV infected approximately 8100 persons in limited geographic areas and the epidemic was substantially controlled within 8 months, but SARS-CoV-2 has infected more than 11.5 million people with more than 537,000 deaths and continues to spread rapidly around the world.

This difference may be explained by the high level of SARS-CoV-2 shedding in the upper respiratory tract, even among asymptomatic subjects [3,6]. Unlike SARS, patients with COVID-19 have the highest viral load near presentation and this could account for the fast-spreading nature of this pandemic [7].

As the outbreak continues to evolve, countries are considering options to prevent the spread of COVID-19 to new areas or to reduce human-to-human transmission in areas where COVID-19 is already circulating. Among these, quarantine measures may delay the introduction of the disease to a country, or delay the peak of an epidemic in an area where local transmission is ongoing. In the context of the current COVID-19 outbreak, the global containment strategy includes rapid identification of laboratory-confirmed cases and their isolation and management, either in a medical facility or at home [8]. WHO recommends that contacts of patients with laboratory-confirmed COVID-19 should be quarantined for 14 days from the last time they were exposed to the patient [9].

Healthcare workers (HCWs) and healthcare facilities have been affected significantly in terms of the number of sick individuals, with a significant risk of COVID-19 transmission in hospitals [10]. In particular, Lombardy has been one of the most severely affected regions in Europe. As a consequence, numerous doctors and nurses have been infected, and experienced symptoms of varying severity. At the beginning of the pandemic, people with COVID-19-related symptoms who did not require hospitalization were not tested, but were quarantined for the entire duration of symptoms and for the next 14 days [11]. In contrast, HCWs were tested early when they developed compatible symptoms, or when they had been contacts of individuals with COVID-19 even if they themselves remained asymptomatic. Contact was defined as prolonged face-to face contact, provision of direct care without the use of proper personal protective equipment, or sharing the same close environment with an individual with COVID-19.

This study analysed the time required to clear COVID-19 infection in a population of HCWs with a positive nasopharyngeal swab.

Methods

This study included 142 HCWs from ASST Rhodense with nasopharyngeal swabs positive for COVID-19 on quantitative reverse transcriptase polymerase chain reaction, diagnosed from 10th March to 10th April 2020, with at least 45 days of follow-up. HCWs were tested if they had compatible symptoms (fever, cough, anosmia, dysgeusia, shortness of breath) or if they had been in contact with individuals with COVID-19. Viral clearance was defined as having two consecutive negative nasopharyngeal swabs within 24–48 h of each other, in the absence of symptoms. After diagnosis, HCWs were tested 2 weeks after symptom recovery and, if still positive, on subsequent weeks. Data regarding gender, age, symptoms, hospitalization and days needed to reach viral clearance were collected and analysed.

Data are shown as means (95% confidence intervals) and percentages. A two-tailed independent samples t-test was used for group comparison of means. The association between demographic and clinical variables with time to viral clearance was analysed with a multi-variate linear regression model. Analyses were performed using Stata Version 15.0 (College Station, TX, USA), and P<0.05 was considered to indicate significance.

Results

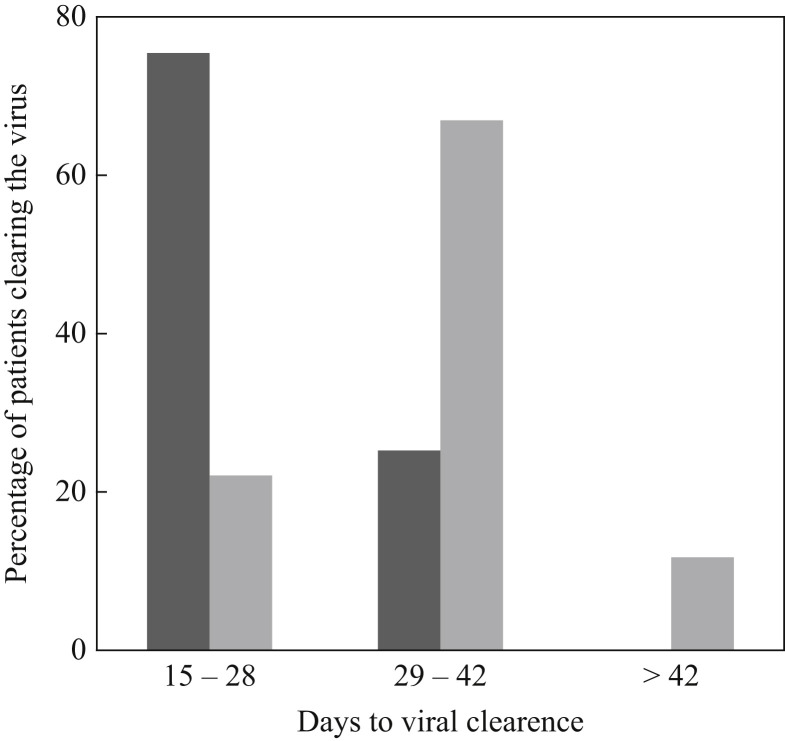

The demographic and clinical characteristics of the study cohort are summarized in Table I . There was a higher prevalence of females (72.5%), and most subjects had fever (75.4%). Twelve subjects (8.5%) were hospitalized due to interstitial pneumonia with moderate–severe respiratory distress, and two subjects (1.4%) required mechanical ventilation for severe respiratory failure. Twenty-eight subjects (19.7%) were asymptomatic. The mean time to viral clearance was 31.8 days, with a maximum of 55 days. Most asymptomatic cases cleared the virus within 28 days (75%), whilst most symptomatic cases cleared the virus between 29 and 42 days (66.7%, Figure 1 ). The mean time to viral clearance was significantly higher in symptomatic cases compared with asymptomatic cases (34.2 and 22 days, respectively; P<0.0001); however, no significant difference in time to viral clearance was observed according to hospitalization (31.5 days for hospitalized cases compared with 34.5 days for non-hospitalized cases; P=0.2). On multi-variate linear regression analysis, the only predictive factor associated with a longer time to viral clearance was the presence of fever (relative risk 11.45, 95% confidence interval 8.66–14.25; P<0.0001); gender, age, hospitalization and other symptoms (anosmia/dysgeusia) were not significantly associated with a longer time to viral clearance.

Table I.

Demographic and clinical characteristics of a cohort of 142 healthcare workers with coronavirus disease 2019.

| Female, N (%) | 103 (72.5) |

| Age, years (mean, 95% CI) | 46.7 (25.5–63) |

| Hospitalized for interstitial pneumonia, N (%) | 12 (8.5) |

| Fever, N (%) | 107 (75.4) |

| Anosmia/dysgeusia, N (%) | 37 (26.1) |

| Patients with at least two symptoms, N (%) | 42 (29.6) |

| Asymptomatic, N (%) | 28 (19.7) |

| Time to viral clearance in general population, days (mean, 95% CI) | 31.8 (16.3–49.3) |

| Time to viral clearance in symptomatic cases, days (mean, 95% CI) | 34.2 (19.5–50.5) |

| Time to viral clearance in asymptomatic cases, days (mean, 95% CI) | 22 (15.5–31) |

CI, confidence interval.

Figure 1.

Percentage of patients clearing the virus by time. Dark grey bars, asymptomatic cases (N=28); light grey bars, symptomatic cases (N=114).

Discussion

This study found that HCWs with COVID-19 need more than 30 days to clear the virus, especially if they had fever at the time of diagnosis. No statistical correlation was found for gender, age or severity of the disease (hospitalized or non-hospitalized). This observation suggests different scenarios for the future management of the pandemic. Although many therapies have been suggested, at present, there are no specific options capable of treating or preventing COVID-19. At present, the only viable intervention that has been proven to decrease the contagion rate seems to be strict quarantine measures. WHO recommends that the contacts of laboratory-confirmed cases of COVID-19 should be quarantined for 14 days from the last exposure [9]. Further, symptom-based screening has only partial utility in the current clinical practice, as asymptomatic carriers may contribute to transmission. In Lombardy, at the beginning of the pandemic, people with COVID-19-related symptoms (cough, fever, anosmia/dysgeusia) were not tested with nasopharyngeal swabs, but were required to remain quarantined for 14 days after symptom recovery [11]. Recently, more data have emerged on the risk of COVID-19 outbreaks in healthcare facilities. Arons et al. [12] reported that the presence of a single positive HCW working in a skilled nursing facility in the USA while symptomatic for COVID-19 led to a significant number of newly diagnosed infected individuals; most of these subjects, although asymptomatic, were able to infect susceptible individuals. The present study on HCWs clearly demonstrated that people infected by COVID-19, even with mild symptoms that do not require hospitalization, need more than 30 days to clear the virus. Asymptomatic subjects clear the virus significantly more quickly than symptomatic subjects, possibly due to delayed access to nasopharyngeal swabbing (they were not tested because of symptoms but because they were contacts of infected individuals). Nevertheless, asymptomatic subjects need more than 3 weeks to clear the virus, and this may represent an enormous problem for control of the pandemic.

This study had some limitations. First, it included a relatively small number of subjects, although they were selected carefully (all the HCWs at the study hospitals with a positive nasopharyngeal swab). Nevertheless, all the subjects included had a positive test in a small and pre-defined time frame (1 month), and nasopharyngeal swabs were repeated, when positive, every subsequent week, which makes the results extremely reliable and generalisable to other clinical contexts.

The rapid spread of COVID-19 across the world and the clear evidence that SARS-CoV-2 can be transmitted by asymptomatic subjects for a long period of time may suggest that the use of SARS-CoV-2 testing should be broadened to include asymptomatic cases, at least in specific settings. These findings, although obtained in a cohort of HCWs, may also be applied to a more general population. Prompt access to testing may be useful to diagnose COVID-19 rapidly, and consequently implement healthcare measures to reduce the risk of transmission. It is suggested that individuals working in hospitals or other healthcare facilities should be tested for SARS-CoV-2 even in the absence of related symptoms to reduce the risk of other, local, outbreaks. As shown in this study, the duration of the quarantine period for symptomatic, untested, individuals should be extended significantly. The results stress that symptomatic subjects, especially those with fever, have a significantly longer period of COVID-19 positivity compared with asymptomatic subjects, and this observation must be taken into consideration to determine the optimal duration of quarantine. Without drastic measures and more severe public health strategies, the management of this pandemic is likely to be ineffective.

Acknowledgements

The authors wish to thank John Tremamondo, MD and Giuseppe De Angelis, MD for their support. In addition, the authors wish to thank their nursing and medical colleagues in ASST Rhodense hospitals.

Conflict of interest statement

None declared.

Funding sources

None.

References

- 1.Chan J.F.-W., Yuan S., Kok K.-H., To K.K., Chu H., Yang J. A familial cluster of pneumonia associated with the 2019 novel coronavirus indicating person-to-person transmission: a study of a family cluster. Lancet. 2020;395:514–523. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(20)30154-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Wang D., Hu B., Hu C., Zhu F., Liu X., Zhang J. Clinical characteristics of 138 hospitalized patients with 2019 novel coronavirus-infected-pneumonia in Wuhan, China. JAMA. 2020;323:1061–1069. doi: 10.1001/jama.2020.1585. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Rothe C., Schunk M., Sothmann P., Bretzel G., Froeschl G., Wallrauch C. Transmission of SARS-CoV-2 infection from an asymptomatic contact in Germany. N Engl J Med. 2020;382:970–971. doi: 10.1056/NEJMc2001468. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Holshue M.L., DeBolt C., Lindquist S., Lofy K.H., Wiesman J., Bruce H. First case of 2019 novel coronavirus in the United States. N Engl J Med. 2020;382:929–936. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa2001191. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Mahase E. Covid-19: WHO declares pandemic because of “alarming levels” of spread, severity, and inaction. BMJ. 2020;368:m1036. doi: 10.1136/bmj.m1036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Wolfel R., Corman V.M., Guggemos W., Seilmaier M., Zange S., Muller M.A. Virological assessment of hospitalized patients with COVID-19. Nature. 2020 doi: 10.1038/s41586-020-2196-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.To K.K.-W., Tsang O.T.-Y., Leung W.-S., Tam A.R., Wu T.C., Lung D.C. Temporal profiles of viral load in posterior oropharyngeal saliva samples and serum antibody responses during infection by SARS-CoV-2: an observational cohort study. Lancet Infect Dis. 2020;20:565–574. doi: 10.1016/S1473-3099(20)30196-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.World Health Organization . WHO; Geneva: 2020. Clinical management of severe acute respiratory infection (SARI) when COVID-19 disease is suspected. [Google Scholar]

- 9.World Health Organization . WHO; Geneva: 2020. Considerations from quarantine of individuals in the context of containment for coronavirus disease (COVID-19) [Google Scholar]

- 10.Nacoti M., Ciocca A., Giupponi A., Brambillasca P., Lussana F., Pisano M. At the epicenter of the COVID-19 pandemic and humanitarian crises in Italy: changing perspectives on preparation and mitigation. NEJM Catalyst. 2020 doi: 10.1056/CAT.20.0080. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Gruppo di lavoro ISS Prevenzione e controllo delle infezioni . Istituto Superiore di Sanità; Rome: 2020. Indicazioni ad interim per l’effettuazione dell’isolamento e della assistenza sanitaria domiciliare nell’attuale contesto COVID-19. Versione del 7 Marzo 2020. Rapporto ISS COVID-19, n.1/2020) [Google Scholar]

- 12.Arons M.M., Hatfield K.M., Reddy S.C., Kimball A., James A., Jacobs J.R. Presymptomatic SARS-CoV-2 infections and transmission in a skilled nursing facility. N Engl J Med. 2020 doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa2008457. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]